Pamela King Cable's Blog, page 11

July 20, 2012

Coal Dust On My Feet ~ part 3

DeDe Nettles was a pistol. At thirty-nine, she carried a .38

Smith & Wesson and could shoot straight. When she slipped it into the

pocket of her apron it felt heavy, like a ball and chain. Yawning, she shuffled

out to the back porch for some fresh air. She stretched and leaned over the

railing hearing … she wasn’t sure. “Could be raccoons trying to get to the

chickens.” Voices—someone’s in the yard. “The whole world’s gone crazy.”

She scurried back into the kitchen

and locked the door behind her. It was the first time she’d turned that lock

since she’d married Thirl and moved into the house on Nicholas Street. After

pouring another cup of coffee, she walked to the front room to rest in her

overstuffed chair. A chair Thirl had bought her for Christmas. He brought it in

on the train from Charleston. The same year he purchased their first

refrigerator and added the bathroom to the back of the house.

Before she sat down she smacked the

chair. An impulse from living in a coal camp, the dust that flew out of it

determined her next cleaning day. She was a small woman and felt like a child

each time she sunk into her chair. The first time she took a seat and saw her

reflection in the windows, she laughed and said she looked like a redheaded

kewpie doll with no legs.

Life’s sorrows showed in her brown

eyes, Thirl had told her. DeDe had seen first hand the hardships of mining life

on women, and she was no exception. Every woman she knew aged quickly. DeDe’s

smiles were few and far between, reserved only for special moments, and mostly

for James Curtis. Up close her skin was a vague meshwork of lines and wrinkles,

like the peel of an orange, only smoother. Petite, but often the largest presence

in the room, her physical size often went unnoticed. She was bound to protect

her own with as much commitment and passion as Joseph Bradley when he decided

to build his coal empire in Widen.

Thirl teased her, how she could

testify about her sanctification one night and shoot a perfect game of pool the

next. DeDe recruited every child on Nicholas Street for Sunday school. She

never missed a church service. And everybody knew she loved her boy. James

Curtis was her prize possession.

For all her religious dreams,

visions, and premonitions, she headed the ladies prayer group every week,

specializing in prayer for the safety of miners. Some folks said she had the

“gift.” Her grandma had it, and so did her mama. A sense of knowing the future,

of hearing what could not be heard by normal folk. A direct line to the

Almighty. She didn’t gossip, but when she spoke—folks paid attention.

DeDe’s hand slipped into her

pocket; her fingers clasped the cold metal of her gun. With her other hand she

reached out to the bookcase beside her chair and lifted the ancient picture of

her grandfather, turning it in the dimly lit room, tilting it this way and

that, gauging the severity of his lifeless face. He was God’s minister, and yet

she wondered if he heard the mine scream before his head snapped toward the

explosion and the rumble of the fireball—before he was incinerated. Or maybe he

never saw it coming. Maybe he was buried by tons of earth without warning.

Maybe his bones were crushed, his organs split open, his senses annihilated,

his life wiped out before he had a chance to understand what was happening. But

she doubted it.

~~~

The coal camp sprawled over the

bottom of the hollow some sixty miles northeast of Charleston, the state

capital. The road to Widen was hilly, twisting and narrow. A broken road with

ruined shoulders and potholes. A yellow sign at the top of the steep hill that

dropped into Widen warned, HILL. Somebody scratched it into the word, HELL.

At the bottom, all along its length

were small houses, occasionally a large one, set back from the road at the edge

of the mountain. A twisting octopus of streets swirled through the valley, not

the typical plaid grids of flatland towns. Although the valley was wide, as

they typically were in that part of the country, one road and one railroad led

in and out of town. Thunderous coal and passenger trains rode the rails and

filled the valley with the sound of screeching brakes and shrill whistle stops.

A loose-plank bridge near the Grille rumbled with a clap of thunder each time a

vehicle drove over the creek below that collected beer bottles, candy bar

wrappers, and cigarette butts. No streets or alleys were paved; that was only

for folks in cities like Charleston and Huntington. Widen’s streets were

covered in slag coal or dirt.

The town was alive with coal. The

Company’s huge gob piles, ominous heaps of mine waste with their guts ablaze,

filled a person’s nostrils with the pungent odor of struck matches. Over thirty

feet high, the graceful slopes of loose coal and sulfurous dirt glowed a soft

orange. The tipple’s steam rose like the breath of a monster. A place where

coal was screened and loaded into railroad cars, the tipple demanded the town’s

attention and tribute. Its silo, locomotive shed and repair shops hugged the company’s

railroad yard.

A company town; Joseph Bradley and

The Elk River Coal and Lumber Company owned it from tipple to barbershop.

Despite the company store, school, post office, bank, movie house, medical

dispensary, YMCA, baseball park, and 310 dwellings, Widen was first and

foremost a coal mine.

The

trees may not have been straighter in Widen, the grass greener, the sky bluer

and the mountains more purple and majestic, but when the mine was producing, it

often seemed so. On fine mornings the locals liked to tell each other that,

indeed, God covered His black gold with these hills, this place—first.

But

the fine mornings had ended. During the first weeks of September after the mine

closed down, the town’s inhabitants remained behind closed doors, clothed in

fear. The school closed, the Grille closed, and even the post office closed the

day after the strikers dug in and parked their cars, sons, and guns at the top

of the road into Widen.

~~~

Inhaling the hills of his childhood, James Curtis watched Odie

Ingram skirt the timber at the far end of the east pasture mounted on a young,

edgy bay colt. Huge maples, oaks and hemlocks towered over everything, standing

still in full foliage on the mountain behind his farm.

Odie worked hard in the mines and

he worked his horses hard. James had been welcome once, but he had no idea what

Odie would say to him now that they were on opposite sides.

James leaned his shotgun against

the fence. He knew most of the younger men had sided with the strikers—he

wasn’t taking any chances. They were boys he’d gone to school with, like Cole

Farlow. Cole was known for his hot head and short fuse. It stuck in James’

memory the day Cole spouted off that if there were ever a strike, he’d shoot a

kiss-ass company man faster than a nigger-lover.

But James knew if the strikers had tried to kill

his dad, they’d shoot at anybody. He respected his dad’s position. He’d

never side with the union even if he did share a few union sympathies. His

love and loyalty to his family far outweighed any feelings for or against the

union. Beyond his duty to honor his

parents, however, he loved Savina with his soul, and today he wanted to explain that to

her father—hoping to keep his place in Odie’s house as his future son-in-law.

James Curtis suspected Odie liked

him well enough, but he'd made it clear. Savina could not marry until she was eighteen.

It was her daddy’s stubbornness, Savina had said. James, in an attempt to be

amiable, respected Odie’s condition. But deep down, James believed Odie would

never allow Savina to marry him. James anticipated an eventual elopement. Many

couples in Clay County married early, but Odie had an innate fear of being

alone since his wife died, so James agreed to wait hoping time would ease his

anxiety.

Odie rode high in his saddle,

appearing taller than he was. Through the mist of daybreak, the dreamy scene

played like a western picture show. In the distance on his favorite colt, Odie

checked the mares for signs of illness or accident. The horses fanned away from

Odie and the colt. Quick in the morning chill, the mares puffed funnels of

breath and shook their heads at the inconvenience.

Odie was not a company man. He

worked the mine for one reason and one reason only—to pay off his farm and to

raise quarter horses. Odie rode up to the barn then jumped down and hitched the

colt to a post, nodding to James, acknowledging his presence. When he ambled

toward the back of the house, James shivered; a chill ran the length of his

body. Gazing up to the dreary sky, winter was on its way … the leaves were

changing, like the rest of his world.

James walked toward the front of

the peeling, sagging farmhouse. A pack of spittle-flinging dogs barked and

paced back and forth on the porch. Chickens roamed freely. Savina quit trying

to fix up the place after her mother died. The yard was covered with junk.

Rusted bedsprings, empty Pennzoil cans, wet newspapers, bald tires, corroded

truck parts … it looked like the house had vomited its insides.

Odie kicked open the screen door

and lifted his gun from his side. Gray drizzle peppered his skin as he stomped

down to the bottom broken porch step. Mud and manure covered his boots. A smile

ticked briefly at the corners of his mouth like a small spasm and he pulled at

his ear with his free hand. Their eyes met with awkward glances. Odie began to

stare at James with the eyes of someone who thinks he’s about to be told a fact

he already knows. His teeth were clamped shut, his top lip drawn back in that

smirking snarl.

James recalled what his daddy had

said about Odie a few days ago. That he changed amazingly little over the last

thirty years. Except for paunchiness around his middle and the loss of some of

his hair, he was the same nice boy he’d gone to school with. James considered

the fact that his daddy didn’t really know Odie.

“Morning, Mister Ingram. Savina in

the house?”

“I figure she’s down by the crick.”

James Curtis nodded and headed

toward the direction of the creek.

“James Curtis!” Odie cocked his

rifle.

James froze, feeling Odie’s hot

stare burn the back of his neck. He turned around. “Sir?”

A twelve-gauge aimed at his head

revealed Odie’s message before he spoke it. “I don’t want you comin’ ‘round

here any more. I don’t want you seein’ my Savina agin.”

Up to now, James was unafraid of

Odie’s intimidation—it was the attempt to keep him from Savina that left him

weak-kneed. “I have a right, Mister Ingram. I have a right to see her. We

agreed.”

Odie’s

blue eyes blazed, considering this. “Comp’ny men have no rights on my

property.”

“Mama thought you’d feel that way.

Said to tell you to remember who helped you on the farm last year when

Josephine died.”

Odie lowered his gun, by only an

inch or two. “I don’t need remindin’. You tell your ma—Thirl and me are even.

Ask Bonehead and Hardrock. Ask ‘em who drove Thirl’s car to the Grille last

night. With him in it passed out and bleedin’ like a stuck pig. I don’t owe

your daddy nothin’, boy. He helped me when Jo died, and it was me that saved

his life last night.”

James opened his mouth but nothing

came out. Except for his eyes, Odie had become a colorless man. His pale skin,

gray hair, gray stubble, dirty gray pants and jacket, and gray cigarette smoke

swirling between his fingers matched the shades of gray in his voice. Pockmarks

and small scars marred his face. Small cauliflower ears poked out from the

sides of his head. The tip of his left ear, which he tugged at whenever he felt

uneasy, was cropped, and his nose lay flat against his face—the result of

shoeing an uncooperative horse some years before.

Despite his unattractive features,

coarse speech and rough manners, he possessed a keen intellect and a profound

capacity for observing the world around him.

James stuffed his hands in his

jacket pockets and shrugged. “You and my daddy been mining together since you

were my age.”

Odie cleared his head and throat,

coughed, then spit a plug of phlegm at one of his dogs. “Boy, you ain’t tellin’

me what I don’t know. Your daddy and me spent years together in them

deep-dark-dank holes in the ground. Goin’ in before sunup and comin’ out after

sundown … never saw daylight for weeks. That cage dropped us like rocks

hundreds of feet into them black holes. Ever’ day we’d walk toward the tipple

together with our dinner buckets, givin’ the comp’ny another day’s labor, never

knowin’ if we’d come home.” Odie lowered his gun further.

“Anybody ever tell you the

definition of slave labor, son?” Odie flicked his cigarette to the ground.

“It’s coalminin’. Men that work a job where they risk their lives ever’ minute

and at the end of the pay period owe more to the comp’ny store than they made.

Debts don’t die with ‘em, neither. They’re passed on to their children. It’s

time the union come in, make things better, work less hours, stricter safety rules

… you heard Zirka … time to let some of the younger fellers in on them

committees. You need to join us, James. Time we make some of the decisions.”

“Daddy said Joseph Bradley has the

highest safety standards in the state. That he kept the mine open during the

Depression so the men could feed their families. Daddy said Bradley pays as

high as union scale.”

“Your daddy has his opinion about

Bradley, I have mine. Bradley owns the damn bank. He owns us, boy. You think

about that. We cain’t take a shit unless Bradley approves it. Now I’m telling

you to get off my land. You best hope the union gets in, then

maybe we’ll talk agin. Otherwise … Savina is off limits to you, son.”

Published on July 20, 2012 08:24

July 19, 2012

Coal Dust On My Feet ~ part 2

James Curtis sat staring at the

wall, his thoughts tumbling over one another in no particular order. He had

assigned himself guard duty on his dad’s bed in the middle of the night an hour

after Hardrock Dodrill and Boney Butcher called Doc Vance from the Grille,

drove Thirl home, and then carried his bloody body into the house. James rose

to his feet, numb and irritable. He stretched and stumbled to the front room

where he fell into his dad’s favorite chair, facing a magnificent ten-point

buck’s head hanging on the wall. A buck they’d hunted for two years, until

Thirl bagged him the Thanksgiving before last. His dad killed it, and he sketched it.

Charcoal drawings from the time he was old enough to hold a pencil collected in

boxes in his mother’s chifforobe. A framed sketch of the live buck hung on the

wall next to its dead head. He hated hunting; killing anything that moved

repulsed him.

James had ridden to work with his dad like he did

every morning. It was called morning by the men who worked that shift, but to

James it was still night, dark and cold and silent. He could hear his dad’s

muffled voice, along with his mother’s, as they said their good-byes. The sound

of his dad’s boots pacing the kitchen floor while he waited for his lunch

bucket haunted him.

Together, he and his dad walked out

of their soot-coated house. They crossed the front yard, along with dozens of

other men crossing their front yards wearing hard hats with lamps attached to

the front, carrying lunch buckets the size of toolboxes. A mass of men leaving

in their pickup trucks and cars, their mouths already chewing plugs of tobacco

to lubricate their throats against the gritty coal dust.

A

first shift supervisor, his dad had worked for Elk River Coal and Lumber as

long as he could remember. Mining provided a good living for his family, he’d

said, and it would do the same for James. Proud to be a miner’s son, James

Curtis followed as expected. He’d worked the mines from the day he graduated

high school, never giving his parents a notion he wanted to leave the

mountains. He’d been a company man from the day he was born.

As a little boy, his mother had educated him in the

importance of coal and how it kept food on their table and heated every home in

the country during winter. “Why, without coal and the miners that bring it to

the surface,” she’d said, “America is no better than some dying country in

Africa with starving children.” James waved to his mother every morning,

stopping at her flower garden—a giant truck tire laid flat and painted white.

James had positioned it next to the dogwood tree in the front yard, a tree

she’d insisted be planted the day he was born.

But it was his dad that squeezed

his hand every morning without saying a word. A quick grasp just after turning

the key in the ignition, keeping his eyes straight ahead. He’d never talked

about their work or the dangers of it. His grip was a fast second of

assuredness that everything was going to be fine—today. It was their secret,

one they shared man to man.

James leaned his head back against

the old chair and closed his eyes. He could smell his dad’s scent of hair tonic

and lye soap. Drifting between sleep and memory, he saw himself as a child

being lifted onto his dad’s shoulders in the Thanksgiving Barn. His dad’s large

leathery hand covered his entire back. He remembered being made to sit still on

a hard church pew, playing with the flexible watchband peeking out from under

his dad’s sleeve, how the gold had worn off, and how it pulled at the hairs on

his arm. His dad sucked peppermints, and whistled old country tunes when he

drove the car. On his dresser, he kept a pickle jar full of change. Each night

his dad emptied his pockets—nickels, dimes, and pennies into the jar, landing

with tinny pings. They were the sounds James listened for as he drifted off to

sleep.

Yesterday, after they’d arrived at

the mine, James Curtis walked behind his dad through a few wisps of smoke left

hanging in the air—the last puffs of his dad’s cigarette. He turned and mumbled

to his son. “Tell your mama I’ll be home late; I have a League meeting after my

shift.”

His dad was fine then, and now he

wasn’t.

He couldn’t recall how long he’d

been sitting there. James got to his feet and walked three steps to the gun

cabinet. Selecting a twelve-gauge shotgun from the rack and a box of shells

from one of the bottom drawers, he shoved three shells into the magazine of the

gun. Then he jacked a shell into the chamber and engaged the safety.

James Curtis paused, peeled off his

Elk River Coal and Lumber Company cap, and tossed it on the buck’s right

antler. Grasping the shotgun in both hands, he opened the back door and slipped

out, out of his mother’s line of sight.

~~~

Doc Vance stood, checked Thirl’s

pulse one last time, then packed his medical bag. “Keep that wound clean and

dressed. Send James Curtis to the office if you need me. Your lucky husband

should be fine. Shove these pills down his throat for the next few weeks. We’ll

watch for infection. A few more inches and that bullet would’ve severed a main

artery in his leg.”

The old doctor hadn’t stopped

talking since he arrived minutes after Thirl was laid on his bed. “You know,

the League is a legal bargaining agency for Bradley’s employees. That committee

was formed to create the company’s welfare plan for its own workforce. I helped

to put that committee together. That League’s a fine a group of men as God ever

made. The League of Widen Miners is company, sure, but it offers medical and

retirement. Don’t those fool strikers remember the mine was open two and three

days a week during the Depression even when the other mines were shut down?

Don’t they remember that?”

“Lord, Doc, they’ve been trying to

strike here since I was a girl. You’re really worried this time, aren’t you?

How long do you think this one will last?”

“How long’s hard to say. As long as

it takes. As long as the United Mine Workers provide their strike fund. John

Lewis and Bill Blizzard are behind this one again, bigger and better organized

than the last strike. I’m afraid it’ll get more violent before it’s over, as

long as their morale doesn’t crack.”

DeDe set her coffee cup on the table by Thirl’s bed.

“I believe I’ve told you, I’m not from Widen. My family came here from Matewan

to get away from the reputation of that town, the violence—and death. Daddy

died here, in Widen, from black lung back in ‘44. Mama … she passed from black

lung too … from thirty years of washing Daddy’s clothes.” DeDe smoothed the

front of her bloodstained blouse, her stare drifting through the windows and

then back to Thirl. Her voice was strained and soft. “My daddy believed Joseph

Bradley owned the safest mines in the state; that’s why we moved here. But the

mines will kill us all, eventually.”

Every man in her life had been or

was a miner, including her son. They all learned the speech patterns of the

coalface. In response to the slightest tap of a pick or a shovel, the mine

communicated. Sighs, hisses, pops, squeaks, groans, crackles, gurgles—each

sound spoke to them and warned of underground water, a weak wall, or a methane

leak. Her own father once told her if the mine choked and found itself about to

crumble, it shuddered first then screamed like a woman in childbirth.

But to DeDe, a long strike was as

dangerous as a cave-in. “I’ve seen the killing a strike will bring. I’ll

protect my own.” Her face already beginning to sag, the carefully groomed hair

already beginning to gray, the eyes already receding into a calm, dark

indifference most people chose to see as insight. She never wore makeup. DeDe

looked down at her bitten half-moon fingernails, then twisted her thick copper

hair into a knot and anchored it at the private part of her neck with bobby

pins. She picked up her pocketbook.

Everybody

in town knew she kept a gun in her purse, including Doc Vance. She walked back

into the kitchen, gripping it against her chest. Doc Vance followed on her

heels.

“DeDe! Now you listen to me … I won’t

have you or any other woman in this town in harm’s way. You let the men handle

this. The company’s recruited its own force. Thirteen good and loyal company

men, I’ve heard. Sworn in as deputies by the County Sheriff to guard the town.

Stay out of it, DeDe, I mean it.” His stare like two grimy nickels and his

tone—stern, “You tell the rest of the women in town, stay close to home and

keep their young’uns in the house after school. I’ve always been fond of your

family. Why, it was just yesterday I delivered James Curtis in this house.”

“That was over nineteen years ago.

I believe you stood by us when we buried a stillborn son five years later. I’ve

had enough heartache, Doc.”

Doctor Vance nodded, avoiding her

eyes, then gathered his jacket and medical bag. “You know management’s secret

weapon when there’s a strike? It’s the women. Mama goes a few months with only

gut paste gravy and biscuits to fix for supper, the old man’s hangin’ ‘round

the house drinkin’ and yellin’ because the kids’re sick and cryin’ and there’s

dirty clothes everywhere and he’s gone most evenin’s to a union meetin’ or

finishin’ his shift on the picket line, comin’ home tired, cold, and

dirty—stinkin’ of liquor. Drives every women I know crazy. They’ll settle

because their wives’ll make them settle.”

DeDe could only nod in return. She

picked up his hat and led him to the door. She was the granddaughter of a

much-revered Baptist minister who had also worked in West Virginia’s coal mines

at the turn of the century. Surely that should count for something with God.

DeDe smiled deceptively and handed the doctor his hat. “Vengeance is mine,

saith the Lord of hosts.”

“You just remember that,” he said

as the screen door spanked shut behind him.

Published on July 19, 2012 09:51

July 18, 2012

Coal Dust On My Feet ~ part 1

~~~Widen, West

Virginia, September 1952~~~

No one knew how long the strike would last.

~~~

Bullets whizzed past Thirl Nettles’

head. Bolting for cover, he leaped into his 1940 Plymouth sedan. His right leg

throbbed with a red-hot searing pain all the way up into his groin. Only

moments before he’d left the League of Widen Miners meeting, strolled past the

tipple and began whistling, “Walking The Floor Over You.”

“Thirl! You

okay?”

“I’ve been

hit!” He slid down on the seat and pressed his hand on the wound, the inside of

his car spinning around his head.

“Hold on!”

The pain was like nothing he’d experienced before.

Not just a pain—an explosion like a live grenade thrown into his body. It

couldn’t be contained. It spread and expanded, searched for ways to escape the

confinement of his skin. His flesh vibrated with it.

Hearing his heartbeat in his ears, he glanced down

at his legs. Dark, warm blood soaked his pants. For a moment, he was sure they

were his dad’s legs, the day they carried him out of the Macbeth mine

explosion—dead. Thirl remained crouched down and motionless on the seat as more

rifle fire struck his car, until dark was the only hand he had to hold before

he passed out.

~~~

Dawn arrived, sifting its dull

light through DeDe Nettles’ lace panel curtains. In the front room, the coal

stove grumbled and ashes rattled into the ash pan. The morning was miserable

cold, raw and damp, the kind of damp that ate into your bones and sucked out

the marrow. It had rained for two weeks straight. Buffalo Creek ran high, its

steep banks muddy and slick.

Thirl

didn’t know who had come to his rescue. He opened his dark eyes to find a

blurry Doctor Vance hovering over him. The other side of the bed was still

made, the pillow tucked neatly under the chenille spread. Groggy, Thirl heard

the doctor’s voice before he passed out again.

Doctor Sherwood Vance, a wide, solid stump of a man,

bald and nearsighted behind wire-rimmed glasses, worked the bulge of muscles in

his jowls to and fro, all while he muttered mostly to himself, but partly to

DeDe.

“Bastards ... low lifes. Miners,

they call themselves, but they have no loyalties, not to their town, not to

their country, not even to each other. They call themselves godly men but

they’d sell their souls for a wooden nickel and a plug of tobacco. They talk

like politicians, up one side and down the other. No respect for the League

tryin’ to make life better for them. What do they expect when somebody like

Jack Hamrick goes berserk in the mine! He deserved to be fired!”

DeDe pulled the blanket over her

husband to keep him warm. She had combed back his oiled hair and washed the

coal dust from his face the best she could. He’d kept a trim figure all these

years despite his diet of fried potatoes, bacon, sausage, and squirrel. And

daily helpings of molasses and biscuits. The man ate for enjoyment, like most

men that worked in a coal mine.

DeDe watched their son, James

Curtis, pull his legs up to his chest and sink into the bottom of his dad’s

bed. He stared at the blood on the floor. At nineteen, he stood as tall and

lanky as Thirl and shared his unreadable dark blue eyes and constant smile. But

where his dad’s hair exuded the color of brown mountain clay, James Curtis had

inherited her burnt red locks, often appearing as if they’d been dipped in

honey when the sun hit at the right angle.

DeDe gave her son’s shoulder a soft

hug, pulled off his cap and kissed the top of his head. Until that moment, she

had no strength to ask questions. Her immediate concern was to assist the

doctor in keeping her husband alive. But anger bubbled just under the surface

of her constraint, searching for a way out of her mouth. She wiped sweat from

her forehead with the back of her hand, then followed the doctor into the

kitchen to prime the pump. Tears dripped down her cheeks as she watched Doc Vance

lean into the sink and scrub her husband’s blood off his hands.

All the nights she lingered near

the sink while Thirl washed up after work in her tiny kitchen, stripped to the

waist, mine dirt covered him like shoe polish. He’d dip his arms over and over

in water up to his elbows, scrubbing with a wire brush and hard granite-like

soap, turning the water black. She thought she’d never again see the true color

of his skin. Black coal dust collected in the creases of his neck and in the

wrinkles of his face. To DeDe, her husband’s hands looked like black bear paws.

She knew he was proud to never have lost a finger. Thirl had told her he

regarded non-life threatening professions as jobs for women and men with too

much education. She saw him as a person who’d been unknowingly thrown into a

world between heaven and hell. She’d heard the Catholics had a name for it. But

unlike everybody else in the coal camp, he was content in the place he

stood—never expecting God to give him more. Even if he damn well deserved it.

A sob caught in her throat. Her

voice and stare were equally painful. “What happened, Doc?”

Doc Vance scrubbed then dried his

hands on a clean towel. “Thirl was there when Harry Gandy fired Jack Hamrick

last week. You know Jack and Opal? I believe they attend your church.”

“Don’t recall his face. I know his

wife.” She wiped her tears with the cuffs of her blouse, then motioned for him

to have a seat at the kitchen table.

“The way I hear it, Hamrick went plum crazy last

week when asked to work in a trackless section of the mine where a new machine

was bein’ given a tryout. Hamrick flew into a rage, shoutin’ the job was unsafe

and that the company was tryin’ to kill its men. Damn fool, took a pop bottle,

broke off the end, and slashed a gash an inch long in his supervisor’s cheek.

Took me an hour to stitch him up. You got any coffee?”

“I’ll

make some,” she said. After rinsing out cups, she filled the coffee pot with

water and Maxwell House, and then turned the electric stove on high. While it

perked, DeDe began scrubbing found blood off the table with jagged sweeps of

her arm. Her elbows pumped sharply. She sniffed more tears back in her head,

but didn’t speak.

Doc Vance removed his

blood-spattered glasses and wiped each lens slowly. “I wasn’t there when Gandy

fired Hamrick. But I walked into Gandy’s office tonight right after the League

meeting. Thirl had just left. Nobody expected miner retaliation. After all,

it’d been a week since they’d fired Hamrick—but seems Jonas Zirka, a

troublemaker in my mind, got everybody all stirred up. When problems come to

the mine and things look bad, there’s always one man who thinks he’s got all

the answers and is willing to take command. Usually, that individual is crazy.

This time, it’s Zirka. Hamrick needed firing. But Zirka’s gonna use it and some

other lame issues to try and bring in the union again. Lies are an infectious

disease. I think Zirka contracted it from some fat cat in the UMW. Anyway, I

heard the gunfire. So did Gandy.”

DeDe stormed back into her

husband’s sick room and glared at her son. “Get a message to Mister Gandy. Make

sure he knows it was your daddy that’s been shot. Use the phone in his office

to call the sheriff.”

“Ain’t no use calling the sheriff,

Mama. Picket line’s done been formed at the top of Widen hill. Doc’s right.

Zirka’s behind it. All that noise last night, those car horns blowing and

moving through the streets? Strike’s on. I was with Savina last night. When I

took her home, it was Odie who told me ‘bout Daddy. I wanted to go straight to

the sheriff. But her daddy said the law won’t come unless somebody’s dead

‘cause Widen is all private property, owned by Joseph Bradley.” She knew her son saw no point in holding

back the truth, even from a woman.

“Odie said he’s gonna strike.”

“Then you get a message to Savina’s

daddy. Tell Odie he best remember who helped him with his farm last year when

Josephine died.” She gave her son a maternal once-over that made him

instinctively straighten up from his slouched position on the bed.

“Yes, Ma’am. Next time I see

Savina.”

“Your girl, Savina, she’s welcome

here James, but Odie’s not gonna allow your skinny company butt on his

property.”

“No, Ma’am.”

She watched James lower his gaze to

her bare feet. They were filthy and spattered with blood. A few of her pretty

red toenails were chipped. They were to attend a church sing in Gassaway

tomorrow. She was going to wear shoes with her toes sticking out. Two nights

before she had held a bottle of red nail polish in front of Thirl, and he

smiled. “Real pretty,” he’d said.

Doc Vance carried two cups of

coffee in from the kitchen. With his elbows fanned out and his eyes on the

cups, he glided up and handed her a cup, stiffly easing himself down on the

chair beside her. They continued the vigil beside Thirl’s bed, watching his

chest rise and fall with each breath, as if at any given moment the body would

change from a wounded man to a dead corpse.

“Odie ain’t too bright,” said Doc.

“The man has only two more years of work to gain a pension, but decides to

strike. Told me he ain’t gonna go on paying fifty cents a month to that no

‘count company League. Damn black throat. Since the rules of pension

eligibility require twenty full years of service, of which Odie already has

eighteen, he’s throwin’ away $1,200 a year for life to save twelve dollars. The

man sleeps with his head up his ass!”

... to be continued

Published on July 18, 2012 12:29

July 17, 2012

A Coal Miner's Granddaughter Remembers

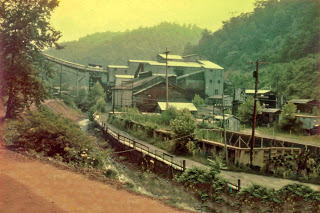

Wash day at Grandma King's house was long and grueling, especially in the winter. I still recall the smell of Grandpa's wet clothes. The stench of the mine refused to budge from the heavy denim. This picture threw me back to those wash days ... when life was simple ... when I was a bitty girl who played among the wet sheets and blue denim hanging on the line.

I loved those days, and my coal mining grandpa. The picture above was taken long before he walked hunched over from working years in the mines. I was born a coal miner’s

granddaughter. That fact inspired the story COAL DUST ON MY FEET. I

never dreamed one day I would write about Widen, West Virginia. The town that

had so haunted my childhood was once involved in a reign of terror between

labor and management that has been said to be the longest and most violent coal

strike in the history of our country. As a child, I was only privy to bits and

pieces of these stories.

I dug deep into the crevices of my

memory. I tunneled through pages of old picture albums Daddy and Mama kept

stored away for years, and found what I was looking for. My grandparent’s

wedding photo. Looking at it, I realized the miners of West Virginia and their

children didn’t romanticize their lives. They lived them, surviving the best

they could. The outside world didn’t exist much past an occasional radio

program or newspaper article. For many years, time stood still in the hollers

and mountains around Clay County. Life for my grandpa, Troy Jennings King,

consisted of his wife Gussie, five children, and a job … mining coal for the

Elk River Coal and Lumber Company.

As a writer, I returned to West

Virginia, to Widen, and immediately began to develop a powerful attachment to

the place. Over the next few months I learned more about the town, and

discovered that my family had deep roots there. Several generations of Kings

and Samples were born and lived in Clay County, all the way back to the

Revolutionary War.

A short time later, I learned of

the role my grandpa played in the Strike of 1952, siding with the company that

had been loyal to him through the Depression. Grandpa always said, "We Hardshell Baptists don't sell our souls that easy." But the family was split on both

sides.

COAL DUST ON MY FEET

is a very real story … in some ways. The strike did happen. Jack Hamrick, Ed

Heckelbech, Bill Blizzard, Charles Frame, John Lewis, Jennings Roscoe Bail,

Governor Marland, and Joseph Bradley were real people who either lived in or

near Widen, and were associated with the strike. Otherwise, the story and

remaining characters are fictional, created from my imagination purely for

storytelling purposes. But the violence from September 1952 to Christmas Eve of

1953 is legendary, and the men who were killed and maimed live on in the

memories of their families to this day.

Families were torn apart, cousin against cousin, father against son—and the

union, though it failed to break the back of the company, changed things.

Eventually, the company closed its doors. In its day, 3,000 people lived in the

coal camp of Widen. Today, there are less than 200. The town folded up except for

the post office and a few that refused to leave—some of them are my relatives.

From these threads of family

history, COAL DUST ON MY FEET was woven. It is a tale of love and

betrayal, forbidden passions and long-buried secrets, of one woman’s struggle with

her heritage and with her God—and the ancient bridge where the real and the

supernatural meet.

But most intriguing to me

personally as I wrote this story was the possibility that I had come by my

stubbornness genes honestly, and that I was more like my grandparents than I

ever dared to think. I dedicated this story to them.

In the coming days, I'll post excerpts from COAL DUST ON MY FEET, one of my favorites from Southern Fried Women . I hope you enjoy it.

Blessings to you and yours.

Published on July 17, 2012 08:16

July 11, 2012

The Journey Never Ends

Yesterday was an exciting day!

We're booking signing and speaking engagements, although not everything is confirmed, we're making headway on the book tour. A tour that looks as though it will take Michael and I around the country this time. From sea to shining sea.

My book trailer is looking fabulous and I'm so pleased. Lots of good news there!

And ... drum roll, please ... Televenge is an Editor's Pick from BookExpo America 2012 from the Library Journal Review. http://reviews.libraryjournal.com/2012/07/books/editors-picks-from-bookexpo-america-2012-from-magick-to-bbq-backlist/

I think back to the days when I just wanted to pull my hair out. Writing at 3 a.m. when the rest of the world slept. The day a few experts told me the book was just too long ... "cut it in half!" "make it a trilogy!" "You're not Nora Roberts, nobody's gonna publish a book this long by a debut novelist!"

The day my watch stopped, the hairdryer started on its own, the TV started when I walked past it, and the bathroom door locked and I couldn't get out ... all on the day I decided not to shorten the book, to stay true to my heart, and to keep certain chapters in the book.

I recall the day I changed the title, but couldn't get used to it, and changed it back. The seventeenth draft. The twenty-second draft. The printers I wore out just printing copy for my readers.

The critiques. Oh, those blasted critiques that sent me reeling! But in the end, shaped the story into crisp prose, shutting the mouth of the author, and never stopping the reader.

Crying over this chapter and that character. Debating on whether or not to dig that deep into my own story and rewrite it. And I remember the day I cut out a character, taking out five chapters in the process. It felt like a funeral.

The day I bawled my eyes out when I typed, The End. But it wasn't the end. It was only the beginning of a journey that has carried me to where I am today. Ready to start the next book.

Well. After the marketing and promotion of Televenge . And a few more good days like yesterday.

Blessings to you and yours.

We're booking signing and speaking engagements, although not everything is confirmed, we're making headway on the book tour. A tour that looks as though it will take Michael and I around the country this time. From sea to shining sea.

My book trailer is looking fabulous and I'm so pleased. Lots of good news there!

And ... drum roll, please ... Televenge is an Editor's Pick from BookExpo America 2012 from the Library Journal Review. http://reviews.libraryjournal.com/2012/07/books/editors-picks-from-bookexpo-america-2012-from-magick-to-bbq-backlist/

I think back to the days when I just wanted to pull my hair out. Writing at 3 a.m. when the rest of the world slept. The day a few experts told me the book was just too long ... "cut it in half!" "make it a trilogy!" "You're not Nora Roberts, nobody's gonna publish a book this long by a debut novelist!"

The day my watch stopped, the hairdryer started on its own, the TV started when I walked past it, and the bathroom door locked and I couldn't get out ... all on the day I decided not to shorten the book, to stay true to my heart, and to keep certain chapters in the book.

I recall the day I changed the title, but couldn't get used to it, and changed it back. The seventeenth draft. The twenty-second draft. The printers I wore out just printing copy for my readers.

The critiques. Oh, those blasted critiques that sent me reeling! But in the end, shaped the story into crisp prose, shutting the mouth of the author, and never stopping the reader.

Crying over this chapter and that character. Debating on whether or not to dig that deep into my own story and rewrite it. And I remember the day I cut out a character, taking out five chapters in the process. It felt like a funeral.

The day I bawled my eyes out when I typed, The End. But it wasn't the end. It was only the beginning of a journey that has carried me to where I am today. Ready to start the next book.

Well. After the marketing and promotion of Televenge . And a few more good days like yesterday.

Blessings to you and yours.

Published on July 11, 2012 10:11

July 8, 2012

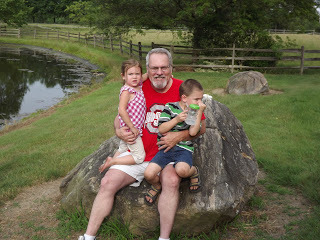

And on this Farm she had some Grandchildren!

Published on July 08, 2012 08:46

July 4, 2012

The Miracle of July 4th

What we celebrate with picnics, apple pie, and fireworks--the colonials gave their lives for. If you love history as I do, you know the horrific fight the early Americans endured so that we could swim in freedom. As you relax around your pools on this hot summer day, just breathe a word of thanks to those who not only gave their lives, but the lives of their families as well. These gallant men who fought with General George Washington, lost battle after battle in unbelievable conditions. Discouraged and disheartened, thousands of men, women and children fought and died to give us the freedoms many of us take for granted.

I do love this holiday. It's summertime at its best. Parades, the grand old flag flying high above the local high school band marching down Main Street, tractors pulling homemade floats, ice cream cones and watermelon. It's a day off work. A day to relax with sparklers for the kids, and a cold beer on the lawn. Baseball, a firey hot sun, and running through the sprinkler. We seem to have become so distanced from the reason we celebrate the 4th, that I wonder if we had the choice would American History be an optional course in our school systems?

Fortunately, American History remains mandatory in our schools. But most of us memorize enough of it just to pass the course, seldom pondering the extreme sacrifices made for us to celebrate July 4th.

The strategic battles, the brutal hand-to-hand combat, and the children that were slaughtered in the process makes me weep. The starving mass of men that turned the tide of war to eventually knock the British to their knees was nothing less than divine intervention. In my humble opinion. As I study more about the birth of our nation, I'm constantly amazed at the odds against us. Out-numbered, out-maneuvered, and out-smarted in one battle after another, I can't image the heart of General Washington. What was it that moved him forward?

One retreat after another, some men wore rags on their feet in horrific winter conditions. It took six weeks just to get a message across the ocean. There were few roads, faulty guns sent by the French, and food for the army (if you could get them to enlist) consisted of salt pork and flour.

You want to talk about miracles? July 4th is a miracle.

Remember that as you load your plate today with hot dogs and potato salad.

Just for a minute ... think of those colonial fallen families and say thanks.

Then go enjoy your fireworks!

Blessings to you and yours.

I do love this holiday. It's summertime at its best. Parades, the grand old flag flying high above the local high school band marching down Main Street, tractors pulling homemade floats, ice cream cones and watermelon. It's a day off work. A day to relax with sparklers for the kids, and a cold beer on the lawn. Baseball, a firey hot sun, and running through the sprinkler. We seem to have become so distanced from the reason we celebrate the 4th, that I wonder if we had the choice would American History be an optional course in our school systems?

Fortunately, American History remains mandatory in our schools. But most of us memorize enough of it just to pass the course, seldom pondering the extreme sacrifices made for us to celebrate July 4th.

The strategic battles, the brutal hand-to-hand combat, and the children that were slaughtered in the process makes me weep. The starving mass of men that turned the tide of war to eventually knock the British to their knees was nothing less than divine intervention. In my humble opinion. As I study more about the birth of our nation, I'm constantly amazed at the odds against us. Out-numbered, out-maneuvered, and out-smarted in one battle after another, I can't image the heart of General Washington. What was it that moved him forward?

One retreat after another, some men wore rags on their feet in horrific winter conditions. It took six weeks just to get a message across the ocean. There were few roads, faulty guns sent by the French, and food for the army (if you could get them to enlist) consisted of salt pork and flour.

You want to talk about miracles? July 4th is a miracle.

Remember that as you load your plate today with hot dogs and potato salad.

Just for a minute ... think of those colonial fallen families and say thanks.

Then go enjoy your fireworks!

Blessings to you and yours.

Published on July 04, 2012 09:29

June 29, 2012

No Guarantees For The Writer

UGH, I certainly don't like to go this long between blog posts! But we're getting down to the wire, three months to go before the book launch!

TELEVENGE

, the dark side of televangelism.

I've been working closely with my publicist at Smith Publicity and my publisher at Satya House, setting up media interviews, booking the launch party, and writing byline articles ... the list is endless and it includes a great deal of time on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and whatever else I can put myself on. The final edits have to be completed before the actual book goes to print, and I'm already working on the next novel ... yes, folks, by the time I lay my head down at night, I've worked twelve hours or more.

The TELEVENGE book trailer is in the works, I'm booking speaking engagements from Ohio to North Carolina to Georgia, and back up the east coast into the Philadelphia area, and my publicist tells me the response to their initial pitch to the media was overwhelming!

I'm hoping all the book buyers at the BEA in New York City are enjoying their advanced reading copies. Hundreds of uncorrected proofs are out there, and this writer can only hope for the best at this point.

When you've done all you can do, poured your heart and scraped-thin soul into your book and then into promoting it, you have to put all the negative thoughts surrounding the publishing industry out of your head. Yeah, you know the odds. Any writer with half a brain who spends any time on the Internet knows the tough road ahead. The thick skin needed for the journey. But we persevere anyway, don't we? What choice do we have?

There are no guarantees. I know that.

It's all I've ever wanted to do. Sure, we crave some measure of success. But this life, my career as a writer, I'm already living my dream. Harper Lee couldn't be any happier than I am at this moment.

I'm already blessed.

Blessings to you and yours.

I've been working closely with my publicist at Smith Publicity and my publisher at Satya House, setting up media interviews, booking the launch party, and writing byline articles ... the list is endless and it includes a great deal of time on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and whatever else I can put myself on. The final edits have to be completed before the actual book goes to print, and I'm already working on the next novel ... yes, folks, by the time I lay my head down at night, I've worked twelve hours or more.

The TELEVENGE book trailer is in the works, I'm booking speaking engagements from Ohio to North Carolina to Georgia, and back up the east coast into the Philadelphia area, and my publicist tells me the response to their initial pitch to the media was overwhelming!

I'm hoping all the book buyers at the BEA in New York City are enjoying their advanced reading copies. Hundreds of uncorrected proofs are out there, and this writer can only hope for the best at this point.

When you've done all you can do, poured your heart and scraped-thin soul into your book and then into promoting it, you have to put all the negative thoughts surrounding the publishing industry out of your head. Yeah, you know the odds. Any writer with half a brain who spends any time on the Internet knows the tough road ahead. The thick skin needed for the journey. But we persevere anyway, don't we? What choice do we have?

There are no guarantees. I know that.

It's all I've ever wanted to do. Sure, we crave some measure of success. But this life, my career as a writer, I'm already living my dream. Harper Lee couldn't be any happier than I am at this moment.

I'm already blessed.

Blessings to you and yours.

Published on June 29, 2012 14:06

June 11, 2012

PICTURES Of A Successful Book Expo!

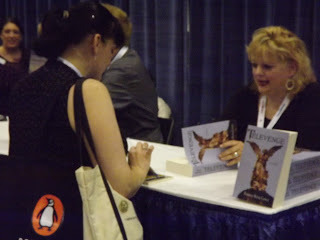

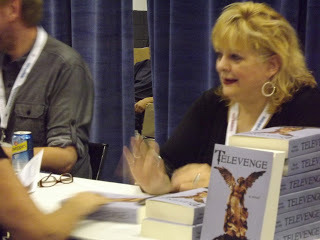

Here I am, signing Advanced Reading Copies at Book Expo America 2012 New York City!

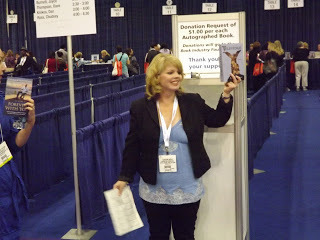

Here I am, signing Advanced Reading Copies at Book Expo America 2012 New York City!Claudine Wolk, my Social Media Guru, spreading the word and bringing the book buyers to my booth!

I signed almost 200 books in an hour and a half!

It was a tremendous success! We're off and running as we prepare for the release date! October 8th! Currently, you can preorder on Amazon.com and from my publisher at Satya House Publications. After 10/8, TELEVENGE will be available everywhere! I can't tell you how excited I am, just waiting for you to get your copy! Thanks to the entire team at Satya House for making this writer's dream come true. Bless you all!

It was a tremendous success! We're off and running as we prepare for the release date! October 8th! Currently, you can preorder on Amazon.com and from my publisher at Satya House Publications. After 10/8, TELEVENGE will be available everywhere! I can't tell you how excited I am, just waiting for you to get your copy! Thanks to the entire team at Satya House for making this writer's dream come true. Bless you all!

Published on June 11, 2012 12:06

June 4, 2012

It All Starts Today!

We're packed and ready, steering the Chevy due east. Heading to New York City today and Book Expo America. Michael and I will hit the Javits Center sometime tomorrow. It isn't our first book party at the Javits. But this time, I'm arriving as a bonifide novelist.

Televenge

is making its debut and I'm pretty stoked, I really must say. I'll be signing books Wed. at Booth 4346 - 10 am, and at Autographing Table 14 - 1 pm. It's certainly the culmination of years of hard work. Although, in some respects its really just beginning.

I'll be meeting with my publisher, my publicist, and hopefully lots of eager readers. It's quite an exciting time in the life of a writer. I've worked a lot of years, wondering if I would just die on the vine. Some mornings I'd sit at my computer and think, "what the hell am doing?" The tears and frustration halted me in my tracks more than once. And I've pulled a lot of splinters out of my hands, building that proverbial platform.

As a writer the hard work is never done, unfortunately. But this week, I'm going to bask in a little bit of sunshine. The book I was meant to write is finished. It's in God's hands now. I'm just going to help Him sell it the best I can. I've had questions as to its genre, and I really have a hard time answering. It's literary, its romance and suspense, thriller, and a bit of the paranormal all rolled into one.

What I do know is that Televenge is a story about the dark side of televangelism. A powerful message of faith and deliveance and strength of the human spirit. A tale of unconditional love. A vivid portrayal of heartbreaking loss and incredible courage. I'm hoping folks will talk about it for a long time.

If you're in NYC this week, and your a bookseller, come see me! I'd love to meet you and hand you a copy of the book.

How cool is that?

Blessings to you and yours.

I'll be meeting with my publisher, my publicist, and hopefully lots of eager readers. It's quite an exciting time in the life of a writer. I've worked a lot of years, wondering if I would just die on the vine. Some mornings I'd sit at my computer and think, "what the hell am doing?" The tears and frustration halted me in my tracks more than once. And I've pulled a lot of splinters out of my hands, building that proverbial platform.

As a writer the hard work is never done, unfortunately. But this week, I'm going to bask in a little bit of sunshine. The book I was meant to write is finished. It's in God's hands now. I'm just going to help Him sell it the best I can. I've had questions as to its genre, and I really have a hard time answering. It's literary, its romance and suspense, thriller, and a bit of the paranormal all rolled into one.

What I do know is that Televenge is a story about the dark side of televangelism. A powerful message of faith and deliveance and strength of the human spirit. A tale of unconditional love. A vivid portrayal of heartbreaking loss and incredible courage. I'm hoping folks will talk about it for a long time.

If you're in NYC this week, and your a bookseller, come see me! I'd love to meet you and hand you a copy of the book.

How cool is that?

Blessings to you and yours.

Published on June 04, 2012 04:36

Pamela King Cable's Blog

- Pamela King Cable's profile

- 54 followers

Pamela King Cable isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.