Jared C. Wilson's Blog, page 9

September 11, 2018

The Lord’s 9/11

He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High

will abide in the shadow of the Almighty.

— Psalm 91:1

Early this morning my 17-year-old daughter rode with me into work. We stopped at a grocery store Starbucks to get coffees, and as she ordered her frou-frou coconut milk choco-yaya, I watched over her shoulder as a TV in the corner showed footage from today’s 9-11 memorial preparations. It took me back to that morning, 17 years ago.

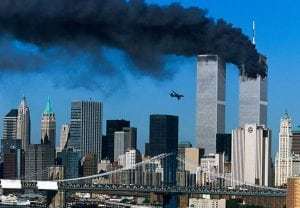

My morning had been routine up until the moment, sitting cross-legged on our master bed, my 3-month-old daughter cradled and snoozing in my lap, I watched the Today Show cut to footage of “a plane crash” in the North Tower of the World Trade Center. At that time, of course, nobody really knew what had happened. The perspective was skewed. The impression was of a small passenger plane that had had an accident. Then watching live, I saw the second plane explode into the South Tower.

More was clear then. But more was cloudy too. I looked down at my little girl and remembered feeling afraid. In the days and months that followed, all the talks of bombings and anthrax and war dominated the news. A year later, a couple of snipers terrorized the Washington, D.C. area. My 1-year-old was toddling around, and like any parent, I wondered, What kind of world will she grow up in?

I sort of know now. Terror hasn’t gone away. Anxiety is at record levels, if pharmaceutical sales are any indication. If you have trouble thinking of things to be afraid of, you probably haven’t looked at a screen in a while. I’m the kind of parent who worries less about Islamic terrorists and more about the crazy driver racing down I-35 while my daughters are figuring out that, inexplicably, the Kansas side is wilder than the Missouri side, as if the Indy 500 begins immediately at the border. But there are daily new things to be frightened about. I don’t think 9/11 didn’t create that, but it is a landmark in our history of fear and of the tragedies that define generations.

Lots of things have changed since 9/11. But at least one thing hasn’t. The Lord reigns.

No, I don’t know all the ins and outs of his reign. I do believe that the one true God is sovereign over all things (Isaiah 46:10, Proverbs 16:4, Colossians 1:17) and that the Son of God upholds the universe by the word of his power (Heb. 1:3). I know that that is cold comfort to some, but it is a world of hope to me. I don’t have to know how this works to be glad it does. At running the risk of trying to be too clever here, I think the Lord’s 9/11 —Psalm 91:1, and the rest of the song—are well worth meditating on over days like this, and days like these.

Psalm 91

He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High

will abide in the shadow of the Almighty.

I will say to the LORD, “My refuge and my fortress,

my God, in whom I trust.”

For he will deliver you from the snare of the fowler

and from the deadly pestilence.

He will cover you with his pinions,

and under his wings you will find refuge;

his faithfulness is a shield and buckler.

You will not fear the terror of the night,

nor the arrow that flies by day,

nor the pestilence that stalks in darkness,

nor the destruction that wastes at noonday.

A thousand may fall at your side,

ten thousand at your right hand,

but it will not come near you.

You will only look with your eyes

and see the recompense of the wicked.

Because you have made the LORD your dwelling place—

the Most High, who is my refuge—

no evil shall be allowed to befall you,

no plague come near your tent.

For he will command his angels concerning you

to guard you in all your ways.

On their hands they will bear you up,

lest you strike your foot against a stone.

You will tread on the lion and the adder;

the young lion and the serpent you will trample underfoot.

“Because he holds fast to me in love, I will deliver him;

I will protect him, because he knows my name.

When he calls to me, I will answer him;

I will be with him in trouble;

I will rescue him and honor him.

With long life I will satisfy him

and show him my salvation.”

(Psalm 9:11 is good too.)

Several years ago I was a guest on a Canadian radio program, and while I was invited under the guise of speaking to the attractional church phenomenon, it turns out that the host and the other guest wanted to grill me as a “Reformed guy” about predestination and such. The conversation was strange, as there was no genuine interest, just ridicule and “gotcha”-type maneuvering. They gave me 30 seconds until the commercial break to resolve how God was sovereign over the Holocaust. But neither God’s sovereignty nor the Holocaust are soundbite kinds of subjects. Declining to defend a view they were clearly trying to set up as horrific, I meekly suggested, “Consider the alternative.”

I thought of that the other day when I posted on Twitter this quote from John Newton: “There is one political maxim which comforts me: ‘The Lord reigns’.” A commenter—one who professes faith in Jesus, as far as I know—replied shortly thereafter, “I’m sure that was a real comfort in Auschwitz.”

Well, I don’t know. Perhaps not. But I can think of one thought much less comforting: “The Lord doesn’t reign.”

Wherever your fears find you today, remember as well as you can that the Lord is sovereign over our 9/11’s. And remember his 9-11, Psalm 91:1: “He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will abide in the shadow of the Almighty.”

September 6, 2018

C. S. Lewis and T. S. Eliot: Unlikely Partners in Mythopoeic Pilgrimage

An author should never conceive himself as bringing into existence beauty or wisdom which did not exist before, but simply and solely as trying to embody in terms of his own art some reflection of eternal Beauty and Wisdom.

— C.S. Lewis, “Christianity and Literature”

Lewis despised the British Modernist innovations from the start. Thinking them unnecessarily rebellious, and even nonsensical, he argued against them in many forums. In letters to friends he criticized the “New Criticism,” sometimes mentioning T. S. Eliot specifically, for whom he reserved special professional ire. His disdain for perhaps Eliot’s most famous poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” is most obvious. In A Preface to Paradise Lost, for instance, Lewis takes Eliot to task as an example of the new poetic excesses. He draws his views from I. A. Richards’s Practical Criticism: A Study of Literary Judgement, and views Eliot’s “Prufrock” as an example of a poet using the wrong “stock responses.”

Lewis sees this practice arising from “a decay in Logic” and a “Romantic Primitivism” (55). For Lewis, the New Criticism represented a fake front, preventing both poet and reader from being completely honest. He specifically criticizes Eliot’s opening lines in “Prufrock”:

Let us go then, you and I,

the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherised upon a table[.] (ll. 1-3)

Lewis comments:

I have heard Mr. Eliot’s comparison of evening to a patient on an operating table praised, nay gloated over, not as a striking picture of sensibility in decay, but because it was so ‘pleasantly unpleasant.’ . . . When poisons become fashionable they do not cease to kill. (Paradise 56-57)

Lewis even responds in a poem of his own, “A Confession”:

For twenty years I’ve stared my level best

To see if evening—any evening—would suggest

A patient etherized upon a table;

In vain. I simply wasn’t able. (ll. 13-16)

It is obvious that Lewis detested the poetic liberties Eliot embraced. The New Criticism, for Lewis, constituted a rejection of the goodness of all poetry before the Modern Era; thus, Eliot could not escape Lewis’s wide net of critique. Lewis argued against Eliot’s techniques in “Shelley, Dryden, and Mr. Eliot,” a rejoinder to Eliot’s own “John Dryden.” Lewis was upset by Eliot’s apparent rejection of Romanticism. Because Lewis himself recalled his early love for Romanticism as the germinations of the Sehnsucht that led him to his religious faith, he stood opposed to Counter-Romantics like Eliot who seemed to criticize Shelley and others, and who attacked the “religion” they thought Romanticism unnecessarily introduced.

Lewis’s dislike for Eliot’s style and ideas finds its way into his fiction as well. The first fictional piece Lewis published after his conversion to Christianity, of course, was The Pilgrim’s Regress, an allegorical tale of his journey to faith (and a twist on Bunyan’s classic allegory). In Regress, Lewis allegorizes Eliot(!) as the Neo-Angular, a man who talks as though he sees things invisible.

The 19th-century literary traditions form much of Lewis’s style, and he was a writer philosophically grounded in and spiritually committed to the past. And, as Patrick Adcock once put it, Lewis believed “20th-century critics have overreacted in their rejection of 19th-century conventions.”

Despite apparent differences, however, Lewis’s and Eliot’s work shares many commonalities, more than perhaps either would admit and more than they are typically given credit for. For all of Lewis’s post-conversion sniping at Eliot’s poetry, the pre-conversion work of both men (Eliot’s conversion to orthodox Christianity was made public in 1927) represent similar concerns. In retrospect, Lewis’s view of myth and “literary religiousness” apply to Eliot’s work. Both poets’ early verse share common concerns, also. As Eliot’s early poetry seeks to recover the “lost story” by creating a verbal collage of divergent philosophies, religions, and folklores, Lewis’s early poetry evidenced his desire to integrate his Modernist atheism with classical mythologies. The two writers appear to echo each other’s concerns.

The controlling metaphor in Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” and most of his other poetry, is that of “broken images.” He writes:

. . . Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats . . . (ll. 20-22)

Eliot’s poetic style resembles this “broken image” idea as it runs stream-of-consciousness through fragments of thoughts and pictures, becoming a type of literary Cubism — abstract on purpose. This metaphor actually resembles one of Lewis’s own. In the second installment of his Space Trilogy, Perelandra, Lewis’s protagonist Ransom reflects:

Our mythology is based on a solider reality than we dream: but it is also at an almost infinite distance from that base. . . . Ransom at last understood why mythology was what it was—gleams of celestial strength and beauty falling on a jungle of filth and imbecility.

For Eliot, the variant world mythologies reflected a universal mythos. Each strand of tradition was a broken image. Piled in a heap, though, with the sun (the Son?) illuminating them, a brighter reality shines through. Lewis’s view concurs: the variant mythologies are individual “gleams” illuminating the “jungle of filth.” The “heap of broken images” and “gleams of strength and beauty” are parallel ideas.

The way these metaphors function in their works carries the idea even further. Their philosophies of myth and literature are not widely divergent. For Eliot, “the living of a myth consists of viewing reality in light of the imagination” (William Skaff, The Philosophy of T. S. Eliot). For Lewis, as Gilbert Meilaender wrote in an 1999 issue of First Things, “imagination was the organ of meaning.” The literature of Eliot and Lewis synthesizes their imaginations with their ideologies. Viewing myth similarly as they do, the prevalence and purpose of allusions to myth, religion, folklore, and literature appear synonymous in their writing.

Eliot’s “The Waste Land” employs the mythic quest as its structural theme. The poem in fact embodies the “form of myth” (Lee Oser, “Eliot, Frazer, and the Mythology of Modernism”). The crossing of water, the acceptance of journey—these are conventions evident in the fragments of descriptions. Eliot apparently believes the universal concept of the quest hints at a true pilgrimage. “The Waste Land” embarks on this pilgrimage, reading the sign posts on the way, watching the heavens and ruminating on the ruins around. Each experience in the poem—love, frustration, adventure, prognostication—are meant as clues to an over-arching story. It is unfortunate that Lewis did not realize the similarity between this approach and his own. Of The Pilgrim’s Regress, Andrew Wheat writes, “Lewis’s pilgrim maps a path between relativist ideology and superstition. Lewis treats the Christian life as a quest and a dialectic rather than a series of questions.”

Implicit in Lewis’s allegorical pilgrimage is the salvation-as-process idea. Given this idea, one would assume Lewis might appreciate Eliot’s processional in “The Waste Land.” And given Eliot’s own conversion, the view of his poetry as processional in the Lewisian sense is not too far off base.

Had Lewis purposefully compared his first published poetry to Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” he would have discovered more similarities than differences. Lewis’s long-form verse Spirits in Bondage, with its subtitle “A Cycle of Lyrics,” represents his immature atheism. At that time in his life, Lewis perceived Beauty as the only true spirituality. Influenced by his experiences in the first World War, Lewis expresses his conviction that nature is malevolent. This is a far cry from his post-conversion views, of course, but the “gleam of celestial beauty” is there—the seed, if you will, of what is filled in later by full Christian theism. The concept behind Spirits in Bondage, differing metrical forms revolving around a central idea, is reminiscent of Eliot’s masterpiece. The cyclical approach suits both poets’ efforts, though Lewis’s work is a collection of poems and Eliot’s is one. Lewis considered his poems in this volume as parts of a whole, however, and this approach is comparable to “The Waste Land”‘s episodes.

From the start, Lewis’s Spirits in Bondage alludes to a figure with a key part in Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” In the first poem, “Prologue” (xli-xlii), Lewis writes:

As of old Phoenician men, to the Tin Isles sailing

Straight against the sunset and the edges of the earth,

Chaunted loud above the storm and strange sea’s wailing . . . (ll. 1-3)

Here, in the first three lines of Lewis’s work, one finds the Phoenician sailor, a critical element to Eliot’s poem. Lewis begins his Cycle with the quest motif, integrating classical archetypes into his presentation of a journey. Eliot’s protagonist in “The Waste Land” is the Phoenician sailor who steers through the ruins and whirlpools of time in search of a turning point in life.

The similarities between the two writers’ mythopoeic sensibilities don’t end there. In Spirits in Bondage, Lewis’s poem “Spooks” (11) follows a man who feels dead inside and thinks himself a ghost to the outside world. In the last stanza he recalls:

So thus I found my true love’s house again

And stood unseen amid the winter night

And the lamp burned within, a rosy light,

And the wet street was shining in the rain. (ll. 113-16)

These lines are eerily similar to Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Prufrock, whether actually inside the room or not, views the party as apart from himself. Both poems feature this sense of detachment, this burning of unrequited love or internal emptiness. The voices in “Prufrock” and “Spooks” are disenchanted, disillusioned, and distanced from life. Even the environmental descriptions in the two poems share images: Eliot has “pools that stand in drains” (l. 18), and Lewis has “wet street shining in the rain” (l. 16). The speakers in each poem echo distance from “the light.”

Returning to Eliot’s “The Waste Land” as a primary indicator of the poet’s mission, more similarities to Lewisian poetry are found. The description of a “turning of the tide” appears in “The Waste Land” both explicitly and implicitly. Eliot writes:

The river sweats

Oil and tar

The barges drift

With the turning tide . . . (ll. 266-69)

This “turning” is a recurring theme in the poem, elucidated most clearly through the Wheel tarot card and illustrating Eliot’s notions of time and history as cyclical. The turning motion is an exquisite companion for the poem’s entire lyrical movement as well. In his later collection of verse, simply titled Poems, Lewis includes a piece called “The Turn of the Tide” (49-51) about the birth of Jesus. The poem singles out the moment of the birth of the Word Incarnate as the turning point in time and space:

The vibrant dithyramb shook Libra and the Ram,

The brains of Aquarius spun round . . . (l. 59-60)

For Lewis, the turning tide is the birth of Christ. For Eliot it is the attempt by man to resist the degenerative flow of “modern” ideas. Eliot’s view emerges from his ideas of culture and history. Lewis’s view is similar to that of Albert Schweitzer, who thought that Christ meant to turn the wheel of history through revolution. Christ failed (according to Schweitzer), was murdered, and then it was his broken body thrust upon the wheel of time that began its turning. (Lewis’s view is not as cynical, but it is still Christocentric.) At the time, Eliot may not have seen Christian Theism as the wheel turner, but he must have eventually. Eliot’s concept of the turning tide can be illustrated as “all paths lead to the same place; we must change directions.” Lewis’s concept can be illustrated thus:

And though there seemed to be, and indeed were, a thousand roads by which a man could walk through the world, there was not a single one which did not lead sooner or later either to the Beatific or the Miserific Vision. (Perelandra)

The cyclical journeys, the attempts at turning the tide, reflect correlative ideas in both writers’ works.

Along with the “tide” similarities, there is another lyrical similarity between Eliot and Lewis. In two instances, they appear to view the process of thought in a like manner. In “The Waste Land,” Eliot writes:

What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

I never know what you are thinking. Think. (l. 113-14)

In a similar passage, in Poems’ “Poem for Psychoanalysts and/or Theologians” (113), Lewis writes:

All this, indeed, I do not remember.

I remember the remembering . . . (ll. 12-13)

The process of thought, as random and disjointed, appears in both excerpts. Also, emphasis is placed on fallacies of thought. Eliot’s speaker admits ignorance (“I never know . . .”), and so does Lewis’s (“I do not remember”). Lewis’s poem embodies the fragmentary approach of Eliot’s.

The many individual allusions in “The Waste Land” are to works and movements Lewis finds influential, also. Eliot alludes to Edmund Spenser’s Prothalamion—“Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song (l. 176)”—and Spenser’s shadow towers over nearly all of Lewis’s work. Referring to Spenser’s Epithalamion, Lewis writes:

“Into this buoyant poem Spenser has worked all the diverse associations of marriage, actual and poetic, Pagan and Christian: summer, landscape, neighbours, pageantry, religion, riotous eating and drinking, sensuality, moonlight—all are harmonized . . . Those who have attempted to write poetry will know how very much easier it is to express sorrow than joy. That is what makes the Epithalamion matchless.”

Like Spenser, both Lewis and Eliot enrich basic allegory with epic ideas.

Another literary figure influential on both men is Dante. In his “Notes on ‘The Waste Land’,” Eliot cites Dante’s influence five times. Of Dante, Lewis writes, “I think [his poetry], on the whole, the greatest of all the poetry I have read,” and, “He has not only no rival, but none second to him.” The prevalent theme in Dante’s work, the mythic journey as picture of Christian afterlife, appears significantly transported to the works of Eliot and Lewis. Eliot cites Milton and Wagner in his “Notes” also, and these two artists are perhaps the two most influential upon Lewis in his adolescence. Lewis writes of his pre-Christian yearnings as stabs of joy. He believes God used works like those by Wagner and Milton to create within him a longing for “the other.” John Bremer writes:

[Lewis] came across a periodical in the schoolroom containing a review of the recent translation of Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods by Margaret Armour; the review included illustrations by Arthur Rackham. One of them, accompanying Act III of Siegfried, shows the startled, awestruck Siegfried, gazing in wonder at the bare-breasted Brunhild whose long sleep he is about to terminate with a kiss. She is the first woman he has ever seen. [Lewis] did not know who Siegfried was, but the picture gave him a sense of “northernness” and a rediscovery of Joy. Later, he was able to buy, with Warren Lewis’s help, the complete volume . . with all the illustrations, and also to collect recordings of parts of the Ring, beginning with The Ride of the Valkyrie. The love of Wagner and all things “northern” continued throughout his life.

Lewis mentions Milton many times in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy. In this passage, Milton joins a list of formative influences, giving us another window into how Lewis’s conversion informed his mythopoeia:

All the books were beginning to turn against me. Indeed, I must have been as blind as a bat not to have seen, long before, the ludicrous contradictions between my theory of life and my actual experiences as a reader. George MacDonald had done more to me than any other writer, of course it was a pity he had that bee in his bonnet about Christianity. He was good in spite of it. Chesterton had more sense than all the other moderns put together; bating, of course, his Christianity. Johnson was one of the few authors whom I felt I could trust utterly; curiously enough, he had the same kink. Spenser and Milton by a strange coincidence had it too.

Milton’s masterpiece, of course, also inspired Lewis’s foremost critical effort, A Preface to Paradise Lost. The influence of both Milton and Wagner upon Eliot’s poetry is significant in his comparison with Lewis. They share these formative influences.

A more curious allusion, and admittedly only a minor note (though still worth mentioning), is Eliot’s allusion to Hinduism. The benediction to “The Waste Land” is extracted from the Upanishads. Eliot writes:

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Shantih shantih shantih[.] (ll. 433-34)

The repetition and spiritual otherness echoed here induce a trance-like reading. The closing is solemn, even “holy.” Interestingly enough, Lewis also had some positive words for Hinduism. While facing which road to formal religion to follow after abandoning atheism, he writes in Surprised by Joy, “There were really only two answers possible: either in Hinduism or in Christianity.” Though eventually accepting Christianity, Lewis believed there was something in Hinduism that set it apart from other religions. Apparently, Eliot believed this, too, as he chose a meditative chant as the climax to “The Waste Land”‘s meta-religious pilgrimage.

The most important similarity between Eliot and Lewis is their view of myth. Mythology, religion, folktale, music, and literature, to them, all hold bits of reality. Between the two of them there is much reliance on classical myths and even the Grail legend. William Skaff writes, “Myths for Eliot, then, give us a glimpse into our unconscious, a sense of Reality as immediate experience.” Similarly, Lewis writes, “Myth is . . . like manna; it is to each man a different dish and to each the dish he needs.” In myth, Lewis and Eliot see a universal acknowledgment of “the other,” of something beyond. Both writers explored myth as a way of finding the truth. In his most focused examination of this concept, the essay “Myth Became Fact,” Lewis writes:

Now as myth transcends thought, Incarnation transcends myth. The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the Dying God, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens—at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical Person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.

. . To be truly Christian we must both assent to the historical fact and also receive the myth (fact though it has become) with the same imaginative embrace which we accord to all myths.

. . . Those who do not know that this great myth became Fact when the Virgin conceived are, indeed, to be pitied. But Christians also need to be reminded—we may thank Corineus for reminding us—that what became Fact was a Myth, that is carries with it into the world of Fact all the properties of a myth. God is more than a god, not less; Christ is more than Balder, not less. We must not be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on our theology.

. . . If God chooses to be mythopoeic—and is not the sky itself a myth—shall we refuse to be mythopathic? For this is the marriage of heaven and earth: Perfect Myth and Perfect Fact: claiming not only our love and our obedience, but also our wonder and delight, addressed to the savage, the child, and the poet in each one of us no less than to the moralist, the scholar, and the philosopher.

Lewis and Eliot both imaginatively embraced this Christian “myth” (Lewis in 1931, Eliot officially in 1927). With this in mind, it is a wonder that Lewis could not recognize the pilgrimage in Eliot’s early poetry. Lewis halted at his disregard for the Modernist style, neglecting an explanation of the purpose behind it. Some critics, like James Tetreault, have begrudged Lewis his cynicism. In an essay published in Renascence Journal, James Tetreault chronicles the two writers’ parallel lives and art, focusing on Lewis’s “unwavering hostility” (257), “major assault” (260), and “major onslaught” (261) against Eliot.

This is probably too much. Critics criticize, and Lewis is no exception. In Eliot, Lewis found the chief spokesman for the Modernist movement he vehemently disagreed with. One can hardly blame him for his aggression. Tetreault appears to credit Lewis’s hostility to his own failed attempts at poetry, insinuating envy as the motivation (264). Anyone at all familiar with the works of Lewis would not arrive at this conclusion so hastily. Lewis was perhaps envious, but there are no other indicators of his jealousy leading to animosity. Lewis had several friends who enjoyed varying degrees of success (Charles Williams, Dorothy Sayers, Owen Barfield), often more than his own. J. R. R. Tolkien is one as well, and Lewis never begrudged “Tollers” his success. Tetreault appears to be grasping at straws here and finally approaches something resembling reasonable when, almost as an afterthought, he reprints Lewis’s words to Walter Hooper, “You know that I never cared for Eliot’s poetry and criticism, but when we met I loved him at once.”

In later years, Lewis and Eliot became friends when both were asked by the Archbishop of Canterbury to serve on the Commission to Revise the Psalter. In a letter to Eliot, Lewis wrote:

You need not sympathise too much: if my condition keeps me from doing some things I like, it also excuses me from doing a good many things I don’t. There are two sides to everything!

We must have a talk—I wish you’d write an essay on it—about Punishment. The modern view, by excluding the retributive element and concentrating solely on deterrence and cure, is hideously immoral. It is vile tyranny to submit a man to compulsory “cure” or sacrifice him to the deterrence of others, unless he deserves it. On the other view what is there to prevent any of us being handed over to Butler’s “Straighteners” at any moment?

I’d have to know more about the Greek of that period to make a real criticism of the N.E.B. (N.T. which is the only part I’ve seen.) Odd, the way the less the Bible is read the more it is translated.

In this letter, one finds evidence of previous conversation. This correspondence finds Lewis and Eliot interacting as friends (Eliot is concerned about Lewis’s health), as literary companions (Lewis apparently thinks highly enough of Eliot’s work to suggest he write an essay), and as colaborers (translation theory is discussed).

What joins Lewis and Eliot together is more important than what makes them different. Lewis later observed, “I agree with him about matters of such moment that all literary questions are, in comparison, trivial.” But, with each closer inspection, their literary differences appear less significant. Eliot and Lewis took up a literary and mythic journey that has challenged mankind throughout history. They weathered storms and charted paths. In terms of literary history, they have helped turn the tide of mytho-literary thinking. In a recent New Yorker essay on religion, John Updike ponders, “What might a faith of the future consist of? . . . Religions are conservative artifacts, made from scraps of others.” Compare this to Lewis’s words in perhaps his most important apologetic work, Mere Christianity: “If you are a Christian, you are free to think that all . . . religions, even the queerest ones, contain at least some hint of truth.”

The future of faith, in the Eliotic and Lewisian sense, in one of gathering up the “heap of broken images,” of bathing in the “gleams of celestial beauty”—these are the “artifacts,” the “scraps.” These are the common elements of our universal experience. Stylistically, Eliot and Lewis may be worlds apart, but thematically they journey together.

August 29, 2018

In Praise of Pastoral Renaissance Men

If you’ve been in church ministry for any length of time, you’ve probably discovered that one of the persistent challenges of your role is the apparent need to treat it like ten other roles. While nearly every pastor is exceptionally gifted in one particular area or another, it is rare that one’s ministry context allows him to camp out in just that one place. As churches grow in scale, it may become more necessary for pastors to serve as specialists, but in most churches, the pastor as “general practitioner” is still the order of the day.

In some evangelical corners, the pastor as generalist may not seem like a particularly cool concept, or even a particularly efficient one, but it certainly has biblical precedent. We have, of course, the various qualifications listed (1 Tim. 3:1-7, Titus 1:5-9, and 1 Pet. 5:1-4). These passages show us what every elder must be, but they shouldn’t be taken as a description of the ideal pastoral personality. Instead, they may show us, alongside the requisite gifting, the requisite pastoral persona—or personas, plural. For instance, in Paul’s letters, we learn that the pastor should be a faithful family man, a gracious host, a disciplined student, and a respected community member. Peter’s list adds the more general descriptor of shepherd. Both apostles of course emphasize that the pastor must be a faithful preacher of the word of truth.

But there’s more. In 1 Corinthians 9:19-23, Paul holds himself up as an example of pastoral versatility in reaching the lost for Christ. As our own cultural landscape continues to change, the faithful local church pastor will also continually renew his foundational commitment to the unchanging gospel of Jesus Christ while at the same time re-evaluate his missional strategy for preaching and applying that gospel. Doing the work of an evangelist, Paul tells the young pastor in 2 Timothy 4:5, is one way to “fulfill your ministry.” In 1 Corinthians 9, then, he’s fleshing out what that might look like. It would seem that even in evangelism and mission, the pastor must “wear many hats.”

Of course, there is a fleshly way many pastors go about trying to “be all things to all people.” This is why the Mayo Clinic warns that those in “helping professions” are at high risk for burnout, because they “identify so strongly with their work that they lack a reasonable balance between work life and personal life and try to be everything to everyone.” Biblically speaking, we’d call this idolatry.

And yet, there is a healthy, God-honoring way for ministers to embrace the call to be “all things to all people.” We could call this more formally the inter-disciplinary work of pastoral ministry. Or we could call it being a renaissance man! A renaissance man is a man of multiple talents. He accesses a wider breadth of knowledge. The pastoral renaissance man, then, is one who gives his whole self to the whole word that he may be of whole use to the whole church.

Not to be confused with a dilettante, who simply dabbles in this and that according to personal whim and cultural fancy, the pastoral renaissance man is a committed exegete, a prayerful missiologist, and a long-suffering shepherd. While the dilettante is outsourcing his study, the renaissance man is a theologian. While the dilettante is scouring the blogs for the latest church-growth techniques, the renaissance man is having coffee with his lost neighbor. While the dilettante is delegating away messy ministry to focus more on “vision,” the renaissance man is feeding the sheep.

Pastoral ministry is not theoretical. It’s not even something you can halfway do.

The challenges of ministry are many, and the bar is set high, but our capacities are limited, and our reach is short.

How in the world can we pull all this off? We can’t, really. That’s one of the other lessons you learn from spending any length of time in ministry. None of us is prophet, priest, and king enough to “be Jesus” to our church and our neighborhood. The challenges of ministry are many, and the bar is set high, but our capacities are limited, and our reach is short.

All the more reason to lean into the fullness of Christ. Pursuit of him will improve our gifts, adoration of him will increase our holiness, and preaching of him will mitigate our weakness. It is good to know as we fail constantly at “pastoral versatility” just how versatile the gospel of Jesus really is.

August 28, 2018

Pastor Only Out of Love

“He must be of a high and great spirit that undertakes to serve the people in body and soul, for he must suffer the utmost danger and thanklessness. Therefore Christ said to Peter, Simon, &c., ‘Lovest thou me?’ repeating it three times together. Then he said: ‘Feed my sheep,’ as if he would say, ‘Wilt thou be an upright minister, and a shepherd? then love must only do it, thy love to me; for how else could ye endure unthankfulness, and spend wealth and health, meeting only with persecution and ingratitude?'”

— Martin Luther, The Table Talk 136

August 23, 2018

To Have Christ is To Have Joy

Until now you have asked nothing in my name. Ask, and you will receive, that your joy may be full.

— John 6:24

You and I live daily within an external — and internal — clash of two worldviews. This tension is the exact tension Jesus himself ministered throughout. here is the worldview we might call Materialism that even Jesus’ followers can’t seem to keep themselves away from, and in which the entire unbelieving world continues to swim. And then there’s the worldview of Christianity. And so many of the disciples’ problems arise from their confusing the worldview of Christianity and the worldview of materialism. And so many of our problems arise from confusing these worldviews too. It’s one reason why taking verses like John 16:23-24 out of context can be so appealing, even though we’re not doing it intentionally.

The worldview of materialism kind of thinks along these lines:

1. Mankind’s greatest need is to have his desires (or feelings) met.

2. Therefore we need things, experiences, and achievements to meet those desires.

3. And then we will be happy.

It begins with our desires (or appetites). It assumes that having “stuff” will satisfy these desires. And then we have these desires met, we will be happy.

Christianity, on the other hand, isn’t totally disinterested in our desires or feelings – it definitely speaks to those things – but it starts much deeper than our desires, and thus it goes much deeper than any other worldview can. Christianity teaches along these lines:

1. Mankind’s greatest need isn’t unmet desires but actually unrealized glory. Our biggest problem isn’t unsatisfied feelings but actually sin. We are disconnected from God, we fall short of his glory, because of our disobedience and rebellion against him.

2. Therefore, what we need is not things, experiences, and achievements, but salvation, redemption, forgiveness, righteousness, rescue – we need primarily the glory of Christ.

3. And once we have Christ (by faith), regardless of our circumstances or feelings (happy or sad), we can have something that runs much deeper than circumstantial feelings. We can have joy. “Fullness of joy,” in fact.

So materialism offers circumstantial experiences and temporary things to satisfy superficial desires. Christianity offers the glory of Christ to satisfy the eternal void inside of our souls.

The problem as I’ve said with the materialistic worldview is that it doesn’t go deep enough. We’re all searching for happiness but Jesus is offering a deep, bottomless, abounding, everlasting well of forever-joy.

The disciples think they’re treasuring Jesus but they only really see the Jesus they want to see, the Jesus they want him to be. And so he knows that when he first dies, they will be undone with confusion and pain. And he knows that when he ascends to heaven after his resurrection their joy at the reunion will be complicated by the sorrow of seeing him depart.

He also knows they will have to endure a very difficult life in the expansion of his mission after he’s gone. They will be threatened, accused, exiled, in some cases tortured, and in many cases executed for their faith.

But he makes them a promise. A promise that is far greater than earthly rewards and earthly successes.

Truly, truly, I say to you, you will weep and lament, but the world will rejoice. You will be sorrowful, but your sorrow will turn into joy. When a woman is giving birth, she has sorrow because her hour has come, but when she has delivered the baby, she no longer remembers the anguish, for joy that a human being has been born into the world. So also you have sorrow now, but I will see you again, and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you. (John 6:20-22)

The pain is a promise. And your pain is a promise.

One day your tears will not only be wiped away, but they will turn to rapturous joy. He will trade your ashes for beauty. Every single hurt your endure will be stored up and returned to you a million-fold in heavenly bliss.

With that in mind, let us turn to the little theology of prayer Jesus offers here in John 6:

In that day you will ask nothing of me. Truly, truly, I say to you, whatever you ask of the Father in my name, he will give it to you. Until now you have asked nothing in my name. Ask, and you will receive, that your joy may be full. (vv.23-24)

Whenever we pray – or whenever we expect something from God – we face the clash of worldviews. Will we walk by sight — materialism – or walk by faith – true Christianity?

The key phrase in vv.23-24 is the repeated “in my name.”

Sometimes people treat this like magic words. “The reason you still suffer is because you don’t have enough faith.” Or “because you’re not praying hard enough.” Like we can add “In Jesus’ name” and get what we want. Like God is some kind of vending machine for our hopes and dreams. But the whole point of vv.23-24 – in fact the whole point of this entire passage – is that our hopes and dreams are not the point. The point is the glory of Jesus Christ!

When you ask anything “in the name of Jesus,” what that really means is that you want the name of Jesus to be magnified more than anything. And if that means the Father must say “no” to your requests – for healing, for comfort, for “stuff” – it means the no is better than the yes, if only the name of Christ is exalted. Whatever you want, Lord, we want! Whatever most brings you glory, Jesus, that’s what we want.

“Only one life, and soon will pass. Only what’s done for Christ will last.”

The promise is that if you will align your purposes and ambitions and prayer requests with God’s purposes, you still may fail but he never will. And in the end, your sorrow will turn into joy.

So many of us have our hearts set on temporary happiness. And that’s fine as far that goes. You’d be weird if you only wanted to be sad all the time. You’d be abnormal if you enjoyed getting hurt! So pray for healing, pray for comfort, pray for things you need. But remember that true joy, which you can have despite your hurt, despite your trials, despite your poverty, despite your lack, can be had in any circumstance because you have Christ, who will never leave you nor forsake you.

He will never let you go.

August 15, 2018

Let Your Internet Yes Be Your Real-Life Yes

Perhaps the shift began when children stopped saying they wanted to be doctors, firemen, and teachers when they grow up and started saying actors, singers, and sports stars. Maybe it began with the manufactured reality of reality TV. Maybe it began when we stopped “going onto the internet” and the internet became the water we swim in. Maybe it began when, out of a need to be viral, every stay-at-home-mom turned her sassy-rants into YouTube shows and every upper-middle-class suburban family turned their life into a reality TV program. I don’t know when it began, but at some point we stopped living like persons and started living like personas.

And the persona has taken over.

The persona allows us to say and do whatever it is our desired audience desires, whatever it takes in fact to maintain the persona and—fingers crossed—turn the persona into a brand. Meanwhile, the person shrinks, and his or her soul along with it.

A couple of times in the last few years I’ve been told “You’re just like you are on Twitter” by people who seem surprised. I’m surprised that they’re surprised. But it’s not exactly true. I’m more extroverted on social media, though I’ve learned to say less about more things, and I don’t usually initiate conversations with people I don’t know. I’ve also been told that I am more ________ than I am online, or less __________ than I am online, suggesting that there is a measuring going on between the real me and the online me and the two me’s don’t exactly look the same. I have thought a lot about that.

Just the fact we think this way is telling. We expect people to be performing. Because a whole lot of us are.

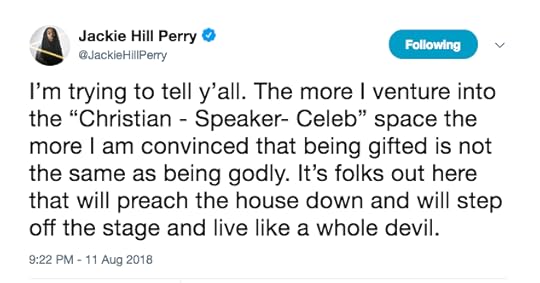

Jackie Perry tweeted this the other day:

This phenomenon is real. But it’s real the other way too. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been contacted by someone concerned about someone they know is an acquaintance of mine who comes off like a jerk online, and I say, “They’re not really like that. If you just knew them, you’d see that’s just how they seem on Twitter,” or whatever. Tone speaks as loudly as text on social media, but perhaps even more loudly. And in any event, it’s easy for all of us to slip into soapbox mode, to battle mode, to “proverbial wisdom” mode in social streams, because the medium favors talking, not listening, and it strips away inconvenient things like looking somebody in the eye, reading facial cues, or even using our real names and faces in the first place. What takes over online is The Persona.

The danger, then, is that what will take over in real life is The Persona. What happens when we are so driven to be known a certain way, to build a certain audience, to accumulate a certain number of subscribers, to establish a certain kind of platform that the persona takes over our real life? We cease being able to see real-life people —whether online or in day-to-day life—as image-bearers, as people who don’t deserve to be used for our platform, derided for our pleasure, mocked for our exaltation, maligned for our advancement. When we think of ourselves as personas, we de-humanize ourselves, and when we de-humanize ourselves, we dehumanize others too. (This is the easy criticism of the anonymous trolls on Twitter—I mean, the ones who aren’t literally bots. They have de-personed their persona, and thus make it easy to dehumanize the real people they target every day.)

Jesus called the Pharisees “hypocrites.” Today we know a hypocrite to be someone who says one thing while doing another. This is a good understanding. But the word’s original meaning—and I think Jesus’s intent—comes from the concept of playacting: ὑποκριταί (hypokritai) refers to actors who painted their faces and played someone they really aren’t. For the Pharisees and scribes, the lie had taken over, become second nature. Outwardly they looked good, but inside they were rotting. But the rot began to seep out through the cracks in the facade. The makeup started running.

We weren’t designed to be double-minded. We weren’t made to playact, to posture. It’s impossible to keep The Persona from taking over. Whatever we put our heart into, whatever we worship, we will become. So if your online persona is abrasive, domineering, argumentative, critical, you don’t get to say for long, “That’s not really me.” You is who you is. Let’s take care that our online yes and no match up with real life, in the right way.

And if we don’t want to cringe when we hear that who we are in real life is who we are online (and vice versa), I suppose we ought to take care how we think, speak, and act in both places. We don’t check the fruit of the Spirit at the door of the login screen. Our obligation to “outdo one another showing honor” (Rom. 12:10) applies as much to our online selves as our in-real-life selves, perhaps more so given the greater temptation to treat people like less than people online.

Come near to God and he will come near to you. Wash your hands, you sinners, and purify your hearts, you double-minded.

— James 4:8

August 14, 2018

Normal Pastor Conference Audio

We were pleased to host the 2nd Normal Pastor Conference at Liberty Baptist Church in Kansas City, MO last weekend, and I’ve been really blessed by the feedback from those who attended. The audio of the messages — from D.A. Horton, John Onwuchekwa, Won Kwak, Nathan Rose, and me — is now available. You can stream or download via the conference website, or via the SoundCloud page.

Messages:

“Passing the Baton of Normal Ministry” – D.A. Horton

“The Normal Pastor’s Family” – John Onwuchekwa

“The Normal Pastor’s Prodigal Gospel” – Won Kwak

“Persevering Through the Perils of Normal Ministry” – Nathan Rose

“The Heart of Normal Ministry” – Jared Wilson

July 24, 2018

Every Christian Must Be a Theologian

Every Christian must be a theologian. In a variety of ways, I used to tell this to my church often. And the looks I got from some surprised souls are the evidence that I had not yet adequately communicated that the purposeful theological study of God by laypeople is important.

Many times the confused responses come from a misunderstanding of what is meant in this context by theology. So I tell my church what I don’t mean. When I say every Christian must be a theologian, I don’t mean that every Christian must be an academic or that every Christian must be a scholar or that every Christian must work hard at giving the impression of being a know-it-all. We all basically understand what is meant in the biblical warning that “knowledge puffs up” (1 Cor. 8:1). Nobody likes an egghead.

But the answer to formal scholasticism or dry intellectualism is not a neglect of theological study. Laypeople have no biblical warrant to leave the duty of doctrine up to pastors and professors alone. Therefore, I remind my church that theology—coming from the Greek words theos (God) and logos (word)—simply means “the knowledge (or study) of God.” If you’re a Christian, you must by definition know God. Christians are disciples of Jesus; they are student-followers of Jesus. The longer we follow him, the more we learn about him and, consequently, the more deeply we come to know him.

There are at least three primary reasons why every Christian ought to be a theologian.

First, theological study of God is commanded.

Having a mind lovingly dedicated to God is required most notably in the great commandment: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” (Matt. 22:37). Loving God with all of our minds certainly means more than theological study, but it certainly does not mean less.

Second, theological study of God is vital to salvation.

Now, of course, I do not mean that intellectual pursuit merits salvation. We are saved by grace alone through faith alone (Eph. 2:8) totally apart from any works of our own (Rom. 3:28), which includes any intellectual exertion. At the same time, the faith by which we are justified, the faith that receives the completeness of Christ’s finished work and thus his perfect righteousness, is a reasonable faith. Faith may not be the same as rationality, but this does not mean that faith in God is irrational.

Saving faith is a gift from God (Eph. 2:8; Rom. 12:3), but it is not some amorphous, information-free spiritual vacuum. The exercise of faith is predicated on information—initially, the historical announcement of the good news of what Jesus has done—and the strengthening of faith is built on information, as well.

Our continued growth in the grace of God, our perseverance as saints, is vitally connected to our pursuit of the knowledge of God’s character and God’s works as revealed in God’s Word. Contrary to the way some idolaters of doubt would have you believe, the Christian faith is founded on facts. Hebrews 11:1 reminds us that for the Christian, faith is not some leap into the dark. Instead, it is inextricably connected to assurance and conviction. It stands to reason that the more theological facts we feast on in the Word, the more assurance and conviction—and thus the more faith—we will cultivate.

Paul tells his young protégé Timothy, “Keep a close watch on yourself and on the teaching. Persist in this, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers” (1 Tim. 4:16). He is reminding Timothy that the sanctification resulting in continual discipleship to Christ necessarily includes intense study of God’s Word.

Third, the study of God authenticates and fuels worship.

True Christians are not those who believe in some vague God nor trust in vague spiritual platitudes. True Christians are those who believe in the triune God of the holy Scriptures and have placed their trust by the real Spirit in the real Savior—Jesus—as proclaimed in the specific words of the historical gospel.

Knowing the right information about God is just one way we authenticate our Christianity. Intentionally or consistently err in the vital facts about God, and you jeopardize the veracity of your claim truly to know God. This is why we must pursue theological robustness not just in our pastor’s preaching but in our church’s music and in our church’s prayers, both corporate and private.

But theological study goes deeper than simply authenticating our worship as true and godly—it also fuels this worship. We must remember what Jesus explained to the Samaritan woman at the well:

True worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father is seeking such people to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth. (John 4:23-24)

We are changed deeply in heart and, therefore, our behavior when we seek deeply after the things of God with our brains. The Bible says so: “Do not be conformed to this world,” Paul writes. “Be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom. 12:2). The transformation begins with a renewing of our minds. As John Piper has said, “The theological mind exists to throw logs into the furnace of our affections for Christ.”

Purposeful theological study of God, as an expression of love for God, cannot help but deepen our love for God. The more we read, study, meditate on, and prayerfully apply the Word of God, the more we will grow in awe of him. Like a great ship on the horizon, the closer we get, the larger he looms.

July 19, 2018

The One Thing We Can Know in Our Hurts

After speaking at a conference once, I spoke with a young man who had suffered from a mental disability all his life. But what he lacked in intellectual capability he did not in theological insight. He said to me that sometimes he asks God why he had to be born with his disability. His brother, he told me, is a smart engineer but an atheist. He said, “Sometimes I ask God, ‘why?’”

So I asked him, “What answer does God give you?”

He paused for a couple seconds and finally answered, “Just that he loves me.”

It was one of the most profound things I’ve ever heard.

We may not always (or ever) understand the ways of God’s providence, why he makes us certain ways or leads us through certain things. But one thing we can know: looking at the cross, we are very loved.

This is perhaps the chief way the Holy Spirit comforts us in our afflictions. He reminds us of what Christ has done for us. And this is not because the Spirit is at a loss as to how to encourage us. He’s not like our well-meaning friends who like to spout cheap inspirational clichés and lame pick-me-ups, mainly out of their own discomfort at our pain. He knows the biggest help we could ever get is from the power of the gospel. And the Spirit’s reminding us of the gospel is entirely according to plan, just as Jesus said:

But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you. (John 14:26)

The Holy Spirit comes to us in our moments of suffering and reminds us of the sufferings of Christ for us, that we are not alone nor or ever, because of the great and eternal love of God given to us through Jesus. Another way to put this is that the Holy Spirit comforts us by reminding us of God’s love.

It is tempting especially in times of darkness to feel abandoned or unloved. Even if others are showing us love, we can doubt the love of God because of the pains we face that only he can alleviate. For some reason he won’t. We begin to reason, like Job’s friends, that we have done something to deserve our disability, our depression, our debilitating pains. But the same Spirit who groans with us in Romans 8:26 reminds us of Romans 8:1—“There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.”

Our great Helper gently and firmly teaches us about Christ, bringing to our remembrance all Christ did for us, including dying. If you are ever tempted to doubt God’s love for you, look at the cross!

The love of God is the most precious thing any person could ever know. It will sustain you like nothing else can and when nothing else will. It will encourage you through the darkest moments of your life. The love of God was put on you, child of God, before the world was even created(!), and it will carry you through your dying day and into the blissful joy of eternal reunion with the source of love himself.

“God is love,” the apostle John tells us (1 John 4:8). This means that in his inter-Trinitarian self, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit share an abounding love for each other that has overflowed and spilled into the bounds of creation, bringing even sinners like us to taste the goodness of God’s divine nature.

The love of God, the psalmist says, is better than your next breath (Ps. 63:3), and so when all else gives way, whether you die young or old, when your eyes close each time in anguished prayer or for the final time, and your lungs give their final whisper, and your heart gives its last beat, the love of God will still be there, never stopping, never ending, lifting you up to glory. And on the day of resurrection, when you enjoy the fullness of creation in a restored earth, it will be love that empowers you and all the redeemed creation, and it will be the love of God that drives our worship of Jesus forever.

When you’re tempted to think God has reached his limit with you, the Spirit reminds you that “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases; his mercies never come to an end” (Lam. 3:22).

When you feel like God has abandoned you, the Spirit reminds you, “The LORD is near to the brokenhearted and saves the crushed in spirit” (Ps. 34:18).

When you expect to be rejected by Christ, the Spirit reminds you that Jesus has gone to prepare a place for you, that where he is, you will be also (John 14:3).

When you are racked by insecurity, the Spirit reminds you that you are safely in the hands of Jesus and nothing can snatch you away (John 10:29).

When you are overcome by fear, the Spirit reminds you that “perfect love casts out fear” (1 John 4:18) and that his own indwelling presence in your life is not conducive to fear, but to power, love, and self-control (2 Tim. 1:7). Indeed, “you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the Spirit of adoption as sons” (Rom. 8:15).

When you are just flat-out overwhelmed by life, and it seems like one thing after another, and you’re tired and desperate and feel hopelessly lost, the Spirit reminds you that

neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord (Rom. 8:38-39).

We could go on and on, because the gospel goes on and on. And the Holy Spirit sent by Christ to comfort us will go on and on to apply it to our hearts in the pain of our darkest days. And when our darkest days are no more, we will go on and on, celebrating the gospel with him for all eternity.

July 17, 2018

Undone by a Sermon for Women

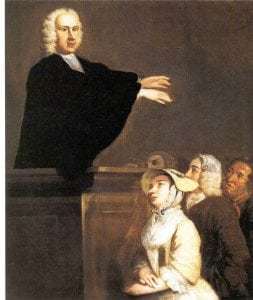

A couple of years ago, I took up the brilliant biography of George Whitefield by Thomas Kidd and was reminded afresh of the spiritual anointing that granted Whitefield unprecedented response to his simple gospel preaching.

When Whitefield preached, the crowds went crazy. Some came to heckle him. Some came to assault him. He had several attempts on his life. But many were ecstatically moved. He would preach, and people would cry out, fall down as though slain in the Spirit, scream, tear their clothes, fall sway to some kind of charismatic joy and conviction.

And though he was a dynamic preacher, it wasn’t just his preaching that caused such effect. Others would take Whitefield’s printed sermons and preach them in their own pulpits, and the resulting gospel havoc would be almost the same.

So as I was reading about all of this incredible response in Kidd’s biography, I thought to myself, I’m going to get some of these sermons. I wanted to see what might happen to me!

I ordered a two-volume collection of Whitefield sermons and began to dig into them straight away. I read one sermon, then two. I read a few more. Kept reading.

And . . . well, nothing happened. No screaming, no fainting. I didn’t rip my shirt off or anything. They are good sermons. Like the preaching of Spurgeon, Whitefield’s exposition is characteristically narrative, imagistic. He doesn’t do heady theology. He is faithfully showing Jesus in short texts and preaching to the “common man.”

I mean, they’re good. But nothing profoundly impressive happened to me. Until—

I came across one particular sermon called “Christ the Best Husband.” Now, I knew a little bit about this message from Kidd’s biography, because he spends a little bit of time recounting the circumstance and consequence of it. See, “Christ the Best Husband” was written for and directed to primarily young women—specifically, to young single women perhaps aspiring to marriage.

I was in a public place reading this selection, and as I sat there reading the sermon for the ladies, I began to weep in front of God and everybody. This is the part that did me in:

Consider who the Lord Jesus is, whom you are invited to espouse yourselves unto. He is the best husband. There is none comparable to Jesus Christ. Do you desire one that is great? He is of the highest dignity, he is the glory of heaven, the darling of eternity, admired by angels, dreaded by devils and adored by saints. For you to be espoused to so great a king, what honour will you have by this espousal?

Do you desire one that is rich? None is comparable to Christ, the fullness of the earth belongs to him. If you be espoused to Christ, you shall share in his unsearchable riches. You shall receive of his fullness, even grace for grace here and you shall hereafter be admitted to glory and shall live with this Jesus to all eternity.

Do you desire one that is wise? There is none comparable to Christ for wisdom. His knowledge is infinite and his wisdom is correspondent thereto. And if you are espoused to Christ, he will guide and counsel you and make you wise unto salvation.

Do you desire one that is strong, who may defend you against your enemies and all the insults and reproaches of the Pharisees of this generation? There is none that can equal Christ in power, for the Lord Jesus Christ hath all power.

Do you desire one that is good? There is none like unto Christ in this regard; others may have some goodness but it is imperfect. Christ’s goodness is complete and perfect, he is full of goodness and in him dwelleth no evil.

Do you desire one that is beautiful? His eyes are most sparkling, his looks and glances of love are ravishing, his smiles are most delightful and refreshing unto the soul. Christ is the most lovely person of all others in the world.

Do you desire one that can love you? None can love you like Christ: His love, my dear sisters, is incomprehensible; his love passeth all other loves: The love of the Lord Jesus is first, without beginning. His love is free without any motive. His love is great without any measure. His love is constant without any change and his love is everlasting.

Oh everything we look for everywhere else but God can only be found in God!

Every greatness, every wealth, every wisdom, every power, every goodness, every beauty, and every love we are longing for can only be found in him, and in him we find the apex of all these virtues and more. Even the best of all earthly versions of these virtues are but pale substitutes. Even the most joyous marriage, the most blessed parenthood, the most adorable of babies virtually disappears in the radiance of his most joyous of joys, most blessed of blessedness, most adorable of adorability as the stars disappear when the sun comes up.

(A version of this post appeared previously in my book The Imperfect Disciple.)