Stephen McClurg's Blog, page 32

February 4, 2021

New Music: Knuckle Dustup

This is the first track from a music project with Justin Litaker called The Spiritual Animal Kingdom. “Knuckle Dustup” started with an improvised track made by Scott Bazar using a nano bug wedged inside a large tuning fork. We edited that track and then wrote the rest of the piece with it as the underlying texture. Thanks for listening!

More soon…

From the Archives: The Terror Test: Test Prep #18

Revisiting the only fragment I have of a zombie book. Originally posted to The Terror Test after George Romero’s death and now resurrected on his birthday.

January 26, 2021

New Review: Lost Chords and Serenades Divine #17

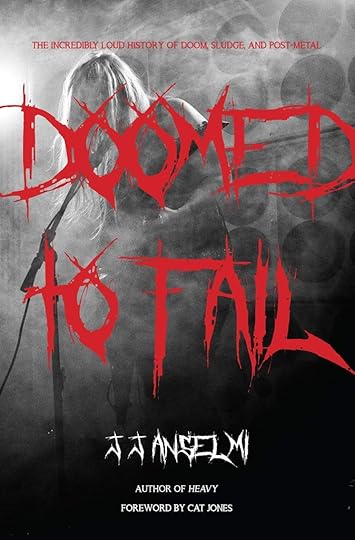

You can read my review of Doomed to Fail over at The Drunken Odyssey.

January 13, 2021

New Review: Lost Chords and Serenades Divine #16

You can read my review of Dua Saleh’s Rosetta EP over at The Drunken Odyssey.

January 2, 2021

New Video: Stull’s “Tear Kettle”

I just finished a video I began at the end of 2017 while just playing with my iPhone camera. After several computer crashes and losing my edit more than once, for maybe a year I thought I had lost all the raw footage. I found it sometime in 2020 while cleaning up files during the pandemic.

Stull has been an important collaboration for me. It’s the first group I started working with after taking six years away from music in order to focus on other work and taking care of my kids.

Happy New Year!

December 15, 2020

New Video: Kelly Coyle’s “Traveling, Sitting Quite Still”

Kelly is my guitar and bass teacher. I started taking lessons in March as a way to get through lockdown. I had always wanted to take lessons, but either always said I didn’t have the money or didn’t deserve them. Getting back into playing music has helped get me through this year.

I’m studying walking bass and a range of folk music with Kelly as well as learning effects enough to attempt some of his improvised pieces we half-jokingly Ambient Americana after something in a Wire article. I’ve been more directly attempting to use fingerstyle guitar on electric whereas Kelly does something else I haven’t quite figured out.

He’s been posting videos of these pieces and, inspired by his use of public domain footage, I wanted to make one for him. I was hoping to capture visually some of what I hear in Kelly’s playing.

December 3, 2020

From the Archives: The Terror Test: Test Prep #17

A Portrait of the Artist as a Glum Man

Originally written for Episode 62 on Eraserhead (1977) and Freaks (1932).

Interviewer: What was Wild at Heart about David?

“Well, it’s about one hour and forty-five minutes.

~An interview with Toby Keeler, recounting a conversation with Lynch

“Believe it or not, Eraserhead is my most spiritual film.”

INT: Why? Elaborate on that, if you will.

“No… I won’t.“

~David Lynch: A BAFTA Interview

INT: Did any of the major studios call [after Eraserhead]?

“I got one call early on […] and I told them I wanted to do Ronnie Rocket. And they said, ‘What is it about?’ […] I told them that basically it was about electricity and a three-foot guy with red hair. And a few more things. They were very polite, but I never, you know, got a call back.”

INT: What is it about?

“It’s about the absurd mystery of the strange forces of existence.”

INT: What else were you doing at the time, besides writing?

“I was building sheds, and whenever you can build a shed, you’ve got it made.“

~Lynch on Lynch

Eraserhead was my Catcher in the Rye. I could relate to Henry. Most protagonists in movies seemed either too rich or beautiful, or were unrealistically heroic. Henry isn’t any of those things. He’s uncomfortable. I could relate to that. Henry seemed like what I felt like on the inside. I had gone to or started at a new school about six times before middle school. I had frequently been the new kid. My father committed suicide when I was in the fifth grade. Decades later, I’m just coming to terms with some of the effects of that. Henry is anxious, afraid, and uncomfortable around people. He’s nervous around girls. He could barely take care of himself, much less anyone around him he was responsible for, including his newborn. He did not have a mask or persona. He was a raw wound with no scab.

I’ve seen Eraserhead more than any other film. I first saw it around age twelve. I’ve owned it on dubbed VHS, two different DVD editions, and now Blu-ray. I had a bootleg t-shirt of Henry Spencer and the iconic title lettering when I was in middle school. I’ve had posters. The score. I’ve played the music live on multiple occasions, one time with a sampled version of the organ in order to replicate it as closely as possible. I have named songs after bits of dialogue.

Seeing Eraserhead was one of the earliest and strongest moments I have of feeling what people refer to as “the power of art.” It was revelatory, ecstatic, cathartic. The world and what it could be–and what art could be–altered after seeing it.

I had seen Elephant Man (1980), Dune (1984), and Blue Velvet (1986). Twin Peaks was starting soon, and while I had seen stills from Eraserhead, I couldn’t find it or anyone who had a copy. My parents and I often watched movies together. In fact, my mom introduced me to The Shining (1980) before I had heard of Stephen King. That movie terrified me, but as a horror fan, I just went back to it again and again. My mom introduced me to Phantasm (1979) and David Cronenberg’s work. I watched It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) by myself in my room as a teenager, but Last House on the Left (1972) was family viewing; we made it a double feature with Eraserhead. We were talking about renting some movies and I brought up Eraserhead, because I knew my mom liked Elephant Man and Dune. We had tried for several years to get Last House, the first film by Wes Craven, because it had scared her so badly when she saw it as a teenager. As one horror fan to another, she wanted to pass that fear onto me, and I wanted it. We called video stores and found one that surprisingly had both. We drove over an hour to rent them, partially because we lived on a barrier island in the Gulf of Mexico, which sounds fancier than the declining fishing village it was.

Star Books and Video was the largest video store I had ever seen. It was a warehouse, really, and had racks of videos so tall that they had to get a ladder out in order to get films down. It was the heyday of video rental. The porn section slowly engulfed the rest of the store until it finally closed, likely swallowed up by the internet.

We decided to watch the Craven film first. It’s a doozy, no doubt, but it wouldn’t affect me for a few years more. My main interests at the time were special effects and monsters and Last House surely has monsters, but they weren’t the ones I was looking for. Watching my choice last meant my parents would likely see about ten minutes and then fall asleep. They did, and meanwhile I had one of the most profound experiences I’ve had with film or any other art.

The lights were off. We had a large screen for the time and I sat right in front of it with a blanket around me, enveloped in it and the world of the film.

I interpreted the narrative–I’ve always seen a story in the film–differently over the years. I think my first interpretation was about the nature of sin and shame. The emblem of both was bound in the repetition of worm-like objects throughout the film: the worm creature Henry hides from his wife Mary, the baby, the snakelike objects The Lady in the Radiator steps on or the ones that Henry pulls from Mary when she’s asleep, the early image of the baby with a sperm-like body that exits Henry’s mouth. I was watching this in the throes of puberty, so it makes sense that I dealt with the film this way. Part of the horror of the film is in fertility or lack of it. Henry’s real and imagined sexual urges, the ones that caused their baby and the ones that cause him to think about and possibly to commit adultery with the woman across the hall, create the shame he has. I think I read The Lady in the Radiator as a form of grace that he goes to once he erases his shame by removing himself from all these personal affairs, including the one to his baby through its murder. I think I read it as a mercy killing, a way to remove shame, sin, and pain, in the way the eraser made of his brain, erases the mark on the paper. It wasn’t until later that I read it as a potential suicide narrative. The Lady in the Radiator as ultimate escape in obliteration.

I’ve read the film as one about the fight of good and evil or sin and innocence and I’ve reversed the place of The Man in the Planet and The Lady in the Radiator. Is she an angel stomping out the relics of sin? Or is she a demon calling Henry to annihilation? Is he a God in the Machine fighting a losing battle? Is he a demonic Hephaestus of the Underworld or subconscious? Are these just images of Henry’s psychological drives?

When I was in college, and still had the dub of the video I made that first night when I watched it for a second time, I began interpreting it as a film about an artist coming to terms with the reality of life, a possible warning for artists about commitments outside their work. My reading may have had something to do with being an art and music major, who later switched to English and philosophy. An artist’s life, particular one that is not charmed, one without professional connections or a trust fund, is difficult in America.There’s a realization that one often comes to: I will have to make a living. Most people will not care about what I write, make, or do.

Later, I thought of the artist coming to terms, or not coming to terms, with fatherly duties. This reading is certainly backed up by some of Lynch’s biography. His first child and his first divorce correspond to the making of the film. When I knew I was going to become a father, I felt confusion and anxiety not knowing what would happen and feeling a deep lack of control over my life. I will say that I did much better than Henry taking care of babies, though it was sometimes terrifying, especially when they were sick. I used the wrong butt ointment once, and had to call my wife at her job, so she could explain to me what to do. I was perplexed and scared when my children were ill. Things were rarely as bad as I imagined, but I felt horribly guilty and sometimes like a failure when I didn’t know what to do.

For better or worse, this has been the story that I’ve connected to my whole life. Now, slouching toward middle age I wonder if I will continue to have a similar connection to the movie. Will I become a version of Mr. X? I’m not quite at “Look at my knees!” but “like regular chickens” and gloating over a family dinner doesn’t seem far off. I imagine being swallowed up by dementia, maybe like the grandmother, and not being able to identify my children, but watching Henry or Mary X as if they strolled out of a family photo album. If I’m lucky, someone will hold my hands so I can stir the oatmeal or toss the salad.

Subscript:

I thought it would be interesting to list works that Lynch has mentioned as influential to him previous to and during the production of Eraserhead. This is by no means meant to be exhaustive. I know he had many more influences in terms of sound and music and in painting (Francis Bacon immediately comes to mind) and other visual art. I just think it’s useful to note the variety of influences on a movie that seems so singular.

The Bible (Lynch has said that a flash of inspiration for Eraserhead came from a particular sentence he read. I don’t believe he’s ever revealed it. )

“The Nose” by Nikolai Gogol

Franz Kafka, particularly The Metamorphosis (I would include The Trial, but I’ve never heard him mention it.)

Robert Henri, The Art Spirit and paintings (Maybe the source of Henry’s name? This would make sense in terms of the artist/father reading. Lynch says this was the most important book for his notions of “The Art Life.”)

Philadelphia Story (1940)

Sunset Boulevard (1950) (Was screened for cast and crew for “mood.”)

Rear Window (1954)

The Fly (1958)

The Hellstrom Chronicle (1971)

Roma (1972) (Fellini, in general. 8 ½ seems an obvious influence.)

Stroszek (1977) (Herzog, in general.)

Jacques Tati

Kubrick (Lynch says he loves his films. Kubrick is said to have screened Eraserhead for friends on more than one occasion and to have referred to it on at least one occasion as “his favorite film.” The opening sequence has been compared to elements of 2001:A Space Odyssey.)

The Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and Transcendental Meditation

An East Indian carved statue of the Buddha: (Lynch relates an epiphanic event that occurred in a museum when he met eyes with the Buddha. The story has lasers or an all-encompassing white light. If the latter, then it corresponds to a scene in the film when Henry is able to hold The Lady in the Radiator.)

November 27, 2020

The Essential If

Here’s a video version of a poem originally published in the Slash Pine Press 2014 Festival Anthology. You can read it and a few other poems inspired by our old mutt Lucy here.

November 23, 2020

From the Archives: The Terror Test: Test Prep #16

Destroy Your Sight With a New Gorgon: “Don’t Look Now” and Macbeth

Originally written for Episode 61 on Don’t Look Now (1973) and C.H.U.D. (1984).

“Do you fear/ things that sound so fair?”

~ The Tragedy of Macbeth, William Shakespeare

“Just chance, a flick of a coin.”

~ “Don’t Look Now,” Daphne du Maurier

In all my viewings of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, I had foolishly not been interested in reading the 1970 story by Daphne du Maurier that inspired it. After tracking it down, I was surprised by the echoes of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which if present in the film, I had missed. I spent time reading the story and working through the play and noticed several recurring images and tropes, including those of vision or seeing (or lack thereof), prophecies, fate, haunting, reversals, motherhood, murderous children, and daggers. At some point I may try to fully explicate the comparisons, but for now, I’m focusing on the beginning and ending of both written works.

The opening scenes set up similar stories of horror, but work inversely. Macbeth opens with The Weird Sisters, three witches rhyming about foul weather and predicting even fouler events. They speak in rhyme and reversals making their speech uncanny, while also giving it the sound of spell casting. One reversal, good is bad and bad is good, sets up a core image of the play. The natural world and natural order are being flipped and the witches, though they can be read as outside these boundaries, possibly represent the unnatural that is taking control over Scotland, most importantly through regicide, the worst crime that could be committed at the time. The opening scene of the witches in a storm is also a version of “a dark and stormy night.”

In “Don’t Look Now,” du Maurier opens the story with a married couple on a dinner date during their vacation in Venice, playing one of their “holiday games” in which they create increasingly perverse narratives about people around them. The scene has a warm playfulness, a couple playing at being detectives like Nick and Nora, from The Thin Man (1934), or one of Hitchcock’s couples. Rather than begin with Gothic gloom, du Maurier sets the reader up for a kind of matrimonial bliss, or recovery of bliss through the healing of dining and travel. She begins in familial mirth, only to slowly displace it. We soon find out that the husband, John, is trying to comfort his wife, Laura, after the death of their daughter from meningitis.

Similar to how the Weird Sisters in their first scene connect themselves to Macbeth by mentioning him and a place that they will meet in the future, John’s first words are about “a couple of old girls” who are trying to “hypnotize” him. We soon find out that the “old girls” are twin sisters on vacation from Scotland, and the blind one has psychic abilities. They believe John has the gift as well, though he denies it and doesn’t trust them.

The Weird Sisters “hypnotize” characters in Macbeth, or seemingly do as their words, especially their reversals, get picked up by others. Their words from the first scene (“Fair is foul, and foul is fair”) are Macbeth’s first words of the play (“So foul and fair a day I have not seen”). These hint at a crisis in the world, good can be evil and evil can be good. Even King Duncan, the character of highest social status and therefore also representing the potential for highest earthly good, echoes the structure of the witches’ reversal in his first scene. When calling for execution on the present Thane of Cawdor and for his title to be given to Macbeth, he says, “What he hath lost noble Macbeth hath won.” Interestingly, the now doomed Thane has no other name, which presents a doubling effect, as if the “Thane of Cawdor” the name itself were cursed. In fact, many versions of the play leave the audience with the notion that mighty Macduff, born of blood and often seen leaving the play covered in blood, becomes the next cursed Cawdor. This may represent the power the Weird Sisters have and may be Duncan foretelling his death. Macbeth also wins the crown “lost” by Duncan.

The first scene in which Macbeth and Banquo confront the witches’ parallels with the opening dinner scene of “Don’t Look Now.” Upon seeing the witches, Banquo, a noble general and Macbeth’s friend, says:

[…]What are these

So withered and so wild in their attire,

That look not like th’ inhabitants o’ th’ Earth,

And yet are on ’t?—Live you? Or are you aught

That man may question? You seem to understand me,

By each at once her choppy finger laying

Upon her skinny lips. You should be women,

And yet your beards forbid me to interpret

That you are so.

Banquo’s words extend the reversals in the play established by the Weird Sisters and Macbeth. They are women, but not (witches were believed to frequently have facial hair). They stand in front of him, yet look inhuman. Already Banquo is unnerved by the “unnatural” qualities of these women. He even associates them with the Devil later. Where Macbeth’s words (“So foul and fair a day”) hint at the ambiguous nature of the post-battle atmosphere, it is one of victory and death. Banquo expresses it in terms of interpretation, of reading, of looking, and the inability to perform these actions. He can’t interpret what the Weird Sisters are, nor does he approve of their prophecies.

In the “holiday game” that John plays with Laura at the opening of “Don’t Look Now,” Laura says, jokingly, that the women across from them are “male twins in drag.” John elaborates on the narrative by describing the twins as criminals in disguise and possible hermaphrodites with hypodermic needles ready to “hypnotize” their prey. For what, exactly, is unclear, but John and Laura, while being playful, are also trying to perversely one-up each other. Similar to Banquo’s wariness at the mixed gender of the witches, John and Laura reveal their uneasiness through jokes about these women being first men in drag, then hermaphrodites, each step transgressing further from their “natural order.”

Just as the Weird Sisters have prophecies for Macbeth, the twins have prophecies for John. Similar to the apparitions that appear to Macbeth and give him warnings that he misinterprets as acknowledgements of his ultimate power, John ignores the warnings, and also misinterprets his own visions, which cost him his life. John misreads what he sees in his own head as Macbeth misreads what the apparition of his own decapitated head tells him. Laura tells him, “I’m not sure of [the twin’s] exact words, but she said something about the moment of truth and joy being as sharp as a sword, but not to be afraid, all was well.” The moment of truth, when John realizes that he has indeed seen the future, is when he experiences his own absurd death by a knife-throwing disfigured dwarf. It’s like a figure straight from Poe invades the short story, just as the apparitions that Macbeth sees begin to take form and invade his own. I suppose the joy could also be the truth? Or maybe the joy is that John gets to recognize the absurdity of the situation.

The inversion comes full circle, though not neatly, with the endings. Macbeth’s Scotland sees the natural order restored, whereas “Don’t Look Now,” shows how lightly tethered to the world ideas like “order” may be. Macbeth battles at the end, there might be some glory in that. John chases what appears to be a child, again, another misreading, that turns unexpectedly deadly. There is consolation and resolution in Macbeth, the natural order, the rightful king and representative of God on Earth, is restored (though one may wonder about Macduff). Not so with du Maurier’s work, where the closest to heaven we get are John’s last words: “Oh, God, […] what a bloody silly way to die …”

November 14, 2020

From the Archives: The Terror Test: Test Prep #15

Carveth vs. Carveth

Originally written for Episode 60 on The ABCs of Death (2012) and The Brood (1979).

“I think the reason why Mommy left… was because for a long time… I kept trying to make her be a certain kind of person. A certain kind of wife that I thought she was supposed to be. And she just wasn’t like that. She was… She just wasn’t like that.”

~ Kramer vs. Kramer (1979)

Watching The Brood in the early ‘80s, I knew it was different from other horror movies, even if I couldn’t articulate how. Unlike the Vincent Price movies that always lurked out of the past, half-velvet, half-malice, or Tourist Trap (1979), which may be the first slasher I saw and seemed like a deviant fairy tale for teens, The Brood felt familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

Years later I discovered Freud’s notion of the uncanny encapsulated that familiar strangeness of early Cronenberg. The architecture, the clothes, and the family dynamics were like the world I lived in, but slightly off. The settings looked like my Michigan neighborhoods, but also didn’t. Like me, the characters bundled up in thick, winter clothing, a component to the overall uncomfortableness of the characters. The literal cold may have affected the metaphorical coldness that some critics see in Cronenberg. Howard Shore’s music echoes this tension with the way he builds phrases with little to no resolution: it provides an atmosphere that is slightly unsettling until it is moreso, like when the brood attacks, and then it echoes the classic Psycho strings of Bernard Herrmann.

Cronenberg’s fourth feature is about the Carveths, Frank (Art Hindle), Nola (Samantha Eggar), and their daughter Candy (Cindy Hinds). More specifically, it is about the divorce and custody battle that ensues between Frank and Nola, a patient at Dr. Hal Raglan’s (Oliver Reed) Somafree Institute of Psychoplasmics. Dr. Raglan’s psychological therapy forces patients to heal themselves through a combination of the talking cure and by manifesting their mental or emotional turmoil as physical change in and on their bodies. Frank fears that Candy is being abused by Nola while she is under Dr. Raglan’s care, and wants to end her visitations at the institute. Raglan will not allow anyone to see Nola, even after family and acquaintances are murdered or beaten by the broodlings, who attack in snowsuited packs.

A few critics, including Stephen King in Danse Macabre, discuss how horror and monsters frequently play to our childhood fears. King writes, “Cronenberg pushes us down the slide; we are four again, and all of our worst surmises about what might be lurking under the bed have turned out to be true.” In a scene from the film, the monster is under the bed, but it is a broodling child that attacks an adult. And, odder still, it is a grandchild (of sorts) attacking its own grandparent, a reversal of the generational violence that King and others see in the film. It’s like the sins of the fathers visiting the fathers, not the offspring. It’s a simple example of how Cronenberg uses horror tropes like the monster-under-the-bed, ones in which we are familiar, yet still infuses something unexpected and frightening into them. When I first saw the film, I dressed in a scarf and one-piece snowsuit just like the brood. The uncanniness of those monsters interested me: a monster to fear, yet one I could be. Where I couldn’t be King Kong, I could be one of them. This was at least one of the features of the film that set it apart from regular monster fare.

Cronenberg’s use of pseudo-scientific research corporations also felt strangely real at a time when you could see commercials for Dianetics on television. In The Brood, we get the Somafree Institute of Psychoplasmics. Other therapies, like recovered memories and self-help psychotherapies, which bear a resemblance to Dr. Raglan’s approach, were mirrored on popular talk shows in the ‘80s and ‘90s. In a way, Oprah became the country’s Raglan. Because there are often notions of psychic power, especially in Scanners (1981), there is also a whiff of the occult to these Cronenbergian institutes reminiscent of other talk show topics of the time like the Satanic Panic.

Though these corporate research institutes are frequent entities in Cronenberg’s oeuvre, he is most famous for what has been termed body horror, a type of horror that focuses on the transformation or decay of the body. I’ve always loved the visceral gross-outs that one expects from these films, but there are a lot of engaging ideas that lend the movies several layers that many genre films just don’t have.

Studying Zen Buddhism led me to one of those layers. Buddhists tend not to differentiate the mind and the body. This idea made me rethink body horror. In Cronenberg’s films, the mind and body are one, which often informs the terror onscreen. The Brood is obvious, though effective. The title can refer to a brood, the offspring, or to brooding, thinking or meditating about something unpleasant. Psychoplasmics, the term itself, hints at this dynamic of thought and body. Dr. Raglan has written a book called The Shape of Rage, and what we find out is that the shape of rage, of brooding, is either sores on the body or broodlings, the killer children who enact the violent thoughts of Nola.

I was an adult before I realized the element of social criticism in the film, though I felt the fear of broken families and divorce in my gut upon first viewing. Also in 1979, one of the most famous films about divorce, Kramer vs. Kramer, came out. Both films are about cruel custody battles. The father calls his son, who’s trying to come to terms with his parents, a “little shit.” There’s an iconic scene in The Brood of the broodlings grabbing Candy through a door, after Nola has said she’s willing to kill her. Even Cronenberg has joked about how similar the films are, only he says his is “more realistic.” How much he’s joking, I don’t know, but the movie is based on his own experience of divorce and a custody battle.

The specter of divorce haunted many families, in elementary school it appeared like having both biological parents at home was becoming the exception, not the rule. I could identify with Candy, though there is a kind of cipherous quality to her performance, but trauma can do this. Many of us were as terrified of divorce as we were of anything lurking under our beds. Even if we hadn’t seen Kramer or Irreconcilable Differences (1984), we had at least heard about them, and knew that there was a child actor in them with whom we could identify.

But this transitioning, of being able to watch Cronenberg’s films like The Brood over the years and discover new ideas has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life as a filmgoer. For example, rewatching the movie, I was surprised by how much of the psychotherapy, Raglan’s psychoplasmics, is bound up with the family drama. The opening features Raglan in a public conference, almost like a talk show, talks with a visibly disturbed patient. Raglan often role plays and here he becomes the patient’s “daddy” and he refers to the male patient as “Daddy’s little girl.” It’s unclear whether the patient is experiencing gender dysphoria (An aspect of the “Somafree” in the name of the institute? One is not defined by body?) or he just won’t “man up.” Getting to the heart, or body, of psychoplasmics, Raglan says, “Don’t speak. Show me your anger. I’m watching you. Go all the way through to the end. Come out the other end.” The patient disrobes showing the polyps growing on his skin, the way to purge difficult emotions with Raglan’s therapy.

This opening scene sets up several themes and energies of the film. Soon after Raglan’s show, the first time we see Frank and Candy together, she says “Oh, Daddy! Daddy!” and we’re set up to believe that this is a proper relationship in comparison to the previous episode of Raglan and his patient. However, Raglan’s episode also echoes the ending when we see Frank and Candy driving away from the institute after Raglan’s death, Frank’s strangulation of Nola, and the death of the brood. Frank and Candy sit together and he says, “We’re going home.” What could that even mean at this point? We also now see Candy’s tears and her own polyps, though Frank, unlike Raglan, either doesn’t want to see her pain and possible anger, or he’s oblivious as the heavy drinking parents of Nola who perished due to her rage. Frank’s notion of home is as spurious as his statement, “You’re the only one for me,” is, though meant to calm his ex and her brood. Those ideas belong in a different movie. Everyone, especially Nola, hears the false ring in it.

Raglan’s language, of not speaking, but showing anger, of going “all the way through” and coming “out the other end,” also aligns with the psychoplasmic polyps, which for Nola, become a kind of pregnancy. Raglan’s language is of birthing. Nola, referred to as his “star student,” literally embodies her anger by giving birth to the brood in wombs hanging from the outside of her body. Dr. Raglan could be seen as a bad stepfather, allowing them free reign until he figures out how to keep them all under control. He’s the one who provides them shelter and clothes.

The patients are Raglan’s brood, but a kind of inverse of Nola’s. Their vision is “distorted;” they see only in black and white. Raglan’s patients appear to confuse categories, maybe they symbolically lack sexual organs, in the way that the broodlings lack them physically. They are like psychological zombies, slaves not to hunger, but to Raglan’s attention. Late in the film, when Frank talks to the patient from the opening scene, he is asked, “Will you be my daddy?” The patient says that his real daddy didn’t care and now Raglan doesn’t even though he knows this patient is “addicted to him.” Similar to how his patients, his children, are trapped in childhood dramas and traumas, we find out in an autopsy that the brood are unborn, unfinished. And though Nola’s can survive for a time without her, they die after their sac depletes, similar to how Raglan’s patients break down away from him.

In one sense, Raglan and Nola are the dysfunctional parents representing all of the generational trauma mentioned earlier. In another sense, they are classic monsters: the mad scientist and his creation: Frankenstein and Frankenstein’s Creature. Nola is also the female creature, the fecund nightmare that Victor feels he has no choice but to destroy. One could read Frank as our Walton, the explorer of Frankenstein’s frame tale, though one not left untouched by the monstrous drama that plays out before him. This Walton gets his fingers dirty, and widens the circle of trauma and guilt, by strangling Nola, which also kills the brood. Walton, the Creature, and a promise of self-destruction are left at the end of the novel, similar to how Frank and Candy, the polyps, and a mention of “home” are at the end of the film.

I’ll stop here, though there always seems to be more to think about with this movie.

One of my favorite comments about Cronenberg’s work that I’ve found comes from David Thomson’s 2004 edition of The New Biographical Dictionary of Film (I first typed that as a “biological” dictionary–word is virus, as Burroughs says). Thomson writes:

Horror for Cronenberg is not a game or a meal ticket; it is, rather, the natural expression for one of the best directors working today. For Cronenberg’s subject is the intensity of human frailty and decay: in short, the body and its many accelerated mutations, whether out of disease, anger, dread, or hope. These are not easy films to take. But how can horror be easy? Anyone born and reckoning on dying needs to confront Cronenberg.

Thomson obviously loves film, but I didn’t expect a comment like this about Cronenberg because Thomson does not just heap praise on filmmakers or actors. He’s a critic, and sometimes a biting one who doesn’t mind tipping sacred cows, much less jabbing genremeisters in the soft and squishies.

I think Cronenberg’s films stay around because they do feel like natural expressions as Thomson notes. If Cronenberg’s subject is human frailty and decay, then it’s no wonder these films have had an eminent rewatchability. We take on different frailties as we continue to grow, to age, and let’s face it, to decay.