Eric Witchey's Blog: Shared ShadowSpinners Blog , page 26

September 9, 2015

Knowing It All

By Christina Lay

Grownups say the darnedest things. I’ve heard a lot of doozies in my time, but the one I’m thinking of today came from a fellow writer and literally made my jaw drop.

I was at the Willamette Writers Conference in Portland, Oregon several years ago and ran into an acquaintance. I asked her if she’d attended any interesting workshops yet and she said, and I quote, “Oh, I’m beyond all that. I know everything there is to know about writing.”

I’ll pause for bit to let that sink that in.

Flash forward to Willamette Writers this year. This is an awesome conference with a mind-bending array of quality instructors and a schedule to make any writer drool. I will admit to a very vague feeling of “been there, done that” when looking over the craft offerings. In years past, I’ve been a craft junkie, always choosing the “How to Write Snappy Dialogue” options over anything to do with the business side of writing. However, this year I was attending with a different agenda, or agendas, to be precise.

For the first time, gathering information to help me make the current project better was not my primary objective. Instead, I had several new identities.

1. A published author looking to market my books

2. A first time publisher looking into the technical side of the business

3. A member of the Wordcrafters in Eugene board looking to spy glean information on how to run a conference by observing the well-oiled machine that is WWC

4. A grizzled veteran looking to meet up and commiserate with pals in the bar, or Burgerville, as it happened to turn out.

Of course I also snuck off to a few craft sessions to feed my always-thirsting-for-literary perfection side.

As I juggled my multiple personalities, scribbled copious notes and tried to keep my head from exploding with all the information I was gathering, I thought about that acquaintance who’d decided she had nothing more to learn. Maybe she’s right. Maybe she had achieved her creative pinnacle and was satisfied with her level of competence. I suppose that is possible. On some planet I have yet to visit.

Personally, I can’t comprehend the idea of ceasing to grow in any aspect of my chosen career. While I’ve attended more workshops and retreats than is healthy for any size pocket book, I still come away with several morsels or tidbits that breathe new life into my approach to storytelling. In addition to new views on craft, I get organization ideas, tips on research, clues on delving deeper, or sometimes inspiration and consolation, the greatest gifts of all for a writer.

My point here isn’t to point and laugh at those who can’t see beyond the publication of The Book (okay maybe just a little) but rather to encourage everyone, no matter what their field of endeavor, to be wary of self-satisfaction. If you truly feel you’ve crammed all the craft you can manage into your skull, perhaps it’s time to start giving back. Take a look at how else you might evolve and contribute. I have friends who teach, host open mike sessions, welcome writing groups into their homes, sit on boards of writing organizations, lead retreats, start up publishing ventures – I admire these people more than I can say and am eternally grateful for writers who know their stuff and yet keep on growing.

I often question my own sanity when I’m juggling all these new projects and challenges, but I have to say I’m never, ever bored. I’m pushing my comfort levels and tentatively experimenting with becoming an adult who has something to offer beyond a competently crafted book.

And if you ever hear me say I know everything there is to know about writing, please dump a barrel of ice water over my head and point me back to this post.

Tagged: author, business of writing, inspiration, Wordcrafters, writing, Writing conferences

September 2, 2015

What is good enough?

“This would be a good death … but not good enough.”

— Frank Miller, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

Leonardo da Vinci said “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” This seems true to experience on some level, but it makes me wonder how the Mona Lisa or Virgin of the Rocks might have ended up if Leonardo hadn’t abandoned them when he did. Could they have ended up better? I don’t know. Could they have ended up worse? Most definitely. So it seems, knowing when to stop is just as critical as knowing how to proceed, or having the perseverance to continue.

Leonardo da Vinci said “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” This seems true to experience on some level, but it makes me wonder how the Mona Lisa or Virgin of the Rocks might have ended up if Leonardo hadn’t abandoned them when he did. Could they have ended up better? I don’t know. Could they have ended up worse? Most definitely. So it seems, knowing when to stop is just as critical as knowing how to proceed, or having the perseverance to continue.

A dose of perfectionism can be a blessing, to fuel an unrelenting drive to press forward with one’s craft and with improvements to a piece. But there comes a time in life of a work of art when further changes could do more harm than good. This can be so clearly experienced in drawing, especially with ink, when a single line can be so quickly regretted. But writing is no different. Perfectionism is a curse, if in pursuit of the unattainable, it drives you past this point.

Recognizing the critical moment is not always easy, but its harbinger is a law of diminishing returns. When each change begins to take more and more consideration for smaller and smaller perceptible improvements, you’re getting close. At some point you must call it good enough, at least for now, and abandon it, as Leonardo would say. Time to submit it, show it, publish it, whatever, and move on to the next piece.

Good enough is not settling. It’s recognizing when something has reached its full potential given your current perception, understanding, and skill. It’s possible you may come back to a piece later, with more experience and greater skill, and see how further improvements can be made. And as long as you see clearly what can be done, that it is an improvement, and you have the skill, time, and inclination to do it, why not? But there’s nothing wrong with letting it be too, as it was in the moment when it was last abandoned. Nothing is perfect, and “there is no exquisite beauty … without some strangeness in the proportions.” (Edgar Allan Poe)

Tagged: art, creative process, editing, fiction, Matthew Lowes, writing

August 26, 2015

Create the Narrative that Creates Our Future, by Eric Witchey

I post this today because this week, over 100 years after scientists first described the carbon emissions greenhouse effect, the President of the United States changed the national narrative on climate change (Svante Arrhenius, 1896).

Source: Alexandrum79 via iStockPhoto.

Create the Narrative that Creates Our Future, by Eric Witchey

A person can be, at least for a little while, logical and rational. Most of us believe we are rational and logical.

Most of us are also wrong.

In fact, even among the well-educated, very few people receive the kind of training that improves actual logical, rational thought. People are trained to apply analytic skills to specific problems, but that’s not quite the same thing. Consider the flame wars that take place when two trained professionals have invested themselves in two separate solutions to the same set of problems. Each solution may solve the problems. Each may have been arrived at via skill and application of sound methodology. However, the battle of egos and emotion that takes place has nothing to do with rational, logical thought.

Human beings are physiologically built so that emotional responses have greater sway over decisions than conscious, executive function.

Certainly, cognitive training increases an individual’s ability to override that tendency. However, a system made up of many people, no matter how well organized, is always irrational. A crowd, a tribe, a company, a state, or a nation is always irrational. In order for a system of people to act effectively on a decision, the decision must fit with the dominant, emotionally satisfying narrative adopted by the individuals who make up that system.

In other words, we internalize stories and act on them as if they are true. Facts are quite irrelevant.

Why do you suppose salesmen and marketers are trained to evoke an emotional response rather than to present facts? Why do you suppose they round up and shoot the independent journalists during a military coup?

Only when facts embed themselves in the system’s foundational irrationality does a culture change for the better—be it a family, a tribe, a community, a county, a state, or a nation.

Cultural inertia is not the tendency of a culture to remain as it is unless acted upon by an outside force. Cultural inertia is the tendency of a culture to act according to an unquestioned narrative until the narrative changes from the inside.

Consider this popular narrative: “The only deterrent to violence is more prisons. If people know they will go to jail, they won’t do the crime.”

Ignoring the logical fallacy of over generalization, consider that it is possible that a potential criminal is so hungry, so afraid, so sick, so threatened by poverty and the absence of less destructive opportunity that the crime has great survival value because the potential gain translates into food and shelter. Even getting caught will at least provide food, shelter, and guaranteed medical support.

A system that acts on the deterrent narrative easily steps forward to embrace this addition: “The cost of prisons is too high for the taxpayer. Privatization can alleviate that cost.” If we believe the former statement, the latter statement is a fairly reasonable step toward the apparent betterment of the social system.

…Unless the private companies receive tax incentives and the judicial system is required to fulfill incarceration quotas in order to maintain profitability.

Here’s a statement that actions demonstrate people accept even if they don’t believe they accept it. “Water in a clear plastic bottle is more pure than tap water because utilities can’t be trusted and magic places exist in the world where water is perfect and we put that perfect, magic water in a bottle so you can buy it. And Convenience. And recycling. Good. Good. Good. Buy more.”

Of course, the more bottled water we buy, the less the local utility is financially viable and the more we complain about our water quality. In other words, we pay thousands of times more for water that came from a tap through a filter outside our town or city, and we thereby undermine the low-cost system that provides our water. And, for spending a lot more, we get the added bonus of loss of public infrastructure and additional layers of environmental damage in production, distribution, and post-consumption.

The facts are known. The facts are even known to most people on the street. The decision to buy that bottle of water is either unconsidered or justified in the moment.

We have serious science that speaks to crime rates, to gun deaths, to global warming, to water losses, to contamination factors, to floating oceanic continents of plastic waste, to the destructive economic effects of corporate feudalism, and to the endless repetition of domestic violence and crime as a result of failed social support and underfunded education.

The facts are available.

However, fact does not have enough social mass to create systemic change.

Factual knowledge has to become part of the tribal folklore that is repeated in ignorance as truth.

Huge campaigns to create the viral narratives that said that seatbelts are good, littering is bad, and cigarettes kill had to be undertaken in order to make the tribal truth a part of the unconsidered oral tradition of the many anthropological tribal systems that, combined, make up our nation. Only when the new narratives took root as fact in hearts and minds did the new narratives replace the old, profit-driven narratives.

Then, cultural change took place.

Interestingly, each of the above changes to national, internalized narrative came about because of the costs to the nation as a whole. Seatbelts translated into lost profits for insurance companies and to lost working person years in the national economy. The same for cigarettes. Littering? Well, that one may have grown out of the zeitgeist of a time when environmental consciousness was first gaining its legs and the power of a public service announcement hadn’t been fully understood by corporate interests. Frankly, I don’t know. I suspect that today the public service ads might be about caution while driving near the crews that our privatized prisons provide in order to keep our national byways scenic.

What is clear is that when a corporate, profit-driven narrative no longer generates profit, the failed story is abandoned. The corporation seeks new products, new markets, and new narratives.

Once a fact-based narrative takes emotional hold, it is much harder to supplant because action based on that narrative creates demonstrable long-term benefit.

People like benefits.

Case-in-point, ACA (Obamacare). Most people have already forgotten that Obama’s original plan was a single-payer solution that has been demonstrated to work in many developed countries. The Republican/Democrat compromise position was the ACA, which is actually based on programs that have failed in other countries.

The compromise came to be because for one side it got us closer to a working plan for the common people. The compromise worked for the other side because history had shown that the ACA would fail very publicly and result in a moment in which existing insurance companies would step up, “compete” across state boundaries, and save the day. The rhetoric was that the new competitive marketplace would result in fewer court cases, lower premiums, etc. None of these benefits of competition are supported by objective study and fact. In fact, the opposite is true (The exception is the court cases because people who buy insurance from a company in another state would have to go to that state to sue. Consequently, it would be harder to sue, so there would be fewer cases).

So, the planned failure was labelled Obamacare in spite of the fact that Obama’s plan was very different. Fortunately for millions of Americans, myself included, the anxiety over medical costs and affordable care was so great that a compromise position intended to fail ended up succeeding in spite of precedent.

The rhetorical association of the ACA with the current administration began immediately. “Obamacare” succeeded as a national narrative. Both advocates and opponents used the term freely. One side used it with pride. The other side used it as a pejorative.

The legal attacks on Obamacare became very serious when numbers started to show that the program might actually work because American healthcare is so screwed up that a system that failed in other countries actually improved the U.S. healthcare system.

By the time the more serious attacks began, it was too late. A new, non-factual narrative was nearly impossible to present to a nation that was clearly seeing immediate benefits.

ACA isn’t perfect. Neither is the single-payer system. The point here is that the ACA narrative’s success is based in the consumer’s emotional need and actual, subsequent benefit.

Facts can support cultural change for the better, but culture only changes when the facts become an emotionally compelling story that can be repeated by people who have no direct knowledge of the science that verified those facts. The change is sustainable when benefits reinforce the tribe’s emotional attachment to the narrative.

Corporate marketing people know the power of story. Ask one.

Politicians know it. They won’t tell you, but even an untrained observer can examine their rhetoric and point to carefully crafted narrative. A trained observer can tell you how and why the rhetoric was designed the way it was.

I know this firsthand because I have been hired to create narratives to present politically volatile concepts as positive change. I also know it because I am a story teller.

Story tellers have always known the power of an emotionally compelling narrative.

The Shaman was the story maker and teller—the conscience and consciousness of the tribe.

Consider that stories told by Sumerian shamanic leaders many thousands of years ago still influence beliefs and behaviors. ISIS justifies beheadings, destruction of property, and slavery based on the modified, interpreted, handed-down narratives from Sumerian stories. Evangelical Christians justify narrative modification of historical fact and science by citing handed-down, interpreted, modifications of the very same Sumerian tales. Both Israelis and Palestinians justify violent action against one another based on differing narrative modifications and interpretations of the same handed-down Sumerian tales.

Are you a little uncomfortable—maybe even angry?

If you are, you are proving the point of this little essay.

Stay with me. Take a breath. Check the facts later. The point of this essay doesn’t change because you are uncomfortable. It doesn’t change if the things I have said are true or untrue. Notice that the only thing actually cited in this essay is the first presentation of greenhouse effects by a scientist. That is a fact.

Right now, consider your emotional response in contrast to a rational response to available historical data. Factual data has no emotional content. Facts just are. If my little narrative above is wrong, it’s just wrong. If it’s right, it’s just right.

Where does the emotional reaction come from?

Regardless, the emotional response to a narrative that doesn’t agree with your own is real. No matter what the facts are, the emotion drives the desire to take action. Why do we live in a world of “trigger warnings?” When do we form those deeply held narratives that affect our emotional responses to everything in life?

We form them in early childhood.

Before we were five years old, we internalized most of the emotional connections to the narratives that cause our reactions in life. How old were you when you went to your first Sunday school class, heard your parents’ first atheist attack on organized religion, attended Hebrew school, went to temple, mosque, church, or synagogue? At what point in the development of your brain did the narrative that caused your reactions form?

The currently available linguistic and cognitive science suggests that a strong emotional response to material like the above is actually a survival response left over from the child who first learned the narrative. In the environment in which the child learned the narrative, acceptance, and by extension food and shelter, were connected to demonstrated belief in the adult-presented narrative.

We are not thinking creatures. We only think we are.

We are feeling creatures.

The facts are only good if they appear in narrative that supports emotional responses.

Little-by-little, linguists, cognitive scientists, sociologists, psychologists, historians, anthropologists, philosophers, and storytellers are making the knowledge of this phenomenon part of cultural awareness. I’m doing it right now.

Consider the development of the science behind our cultural understanding of climate change. The first presentation of the concept of greenhouse carbon emissions impact on the future environment was presented late in the 19th century—over 100 years ago. Not quite that long ago, I wrote bad poetry about climate change when I was in high school. Back then, the Carter administration worked hard to address the known issues of fossil fuel dependence and emissions outputs. Do you remember when coal-fired power plants were first required to install re-burners and scrubbers? Do you remember when catalytic converters were first required on automobiles? Thank you Jimmy Carter for all you have done for the individuals that make up our nation and for the planet as a whole. May you beat your cancer and live long. We need your personal interpretation of the handed-down stories of the Sumerians. I think you got it right.

Do you remember that before Reagan was governor of California, California residents could go to state universities for free? After Reaganomics installed the narrative that higher education is a personal privilege rather than a national investment in the future, no such luck.

Nationally, Reaganomics put an end to the liberal nonsense of the Carter administration.

The very successful electric car experiment disappeared without trace. New, horribly incorrect narratives about emission controls pushed deadlines out into the future. Education funding was cut. Private colleges were encouraged. Banking restrictions were cut. Some of us remember the first time we saw a credit card that offered a deferred 20% or more interest rate. Before Reaganomics, interest rates like that were illegal and, quite literally, only offered by loan sharks. Mining in federal lands became easier. Regulatory agencies became run by people from the industries they were intended to regulate. Okay, that last one was a lie. That wasn’t really new. It just got worse. Prison and schooling for profit gained support.

Am I making a partisan attack?

No. I’m registered an Independent. I’m pushing buttons to get people to test their personal narratives. Most of the above is verifiable public record. The sad part is that the bits people agree with, they won’t check. The bits they disagree with, they won’t check. In other words, as long as we are comfortable in our beliefs, we don’t bother with facts.

People who actually want to test their personal narratives, and this narrative, can simply go to the federal government sites (.gov–not .com, .bus, .edu, .org, or any other dot) that track and present law making, modification, and federal spending numbers. Go to several. Each agency is presenting its own narrative.

Hurry, though.

Legislation is in the works to make it illegal for citizens to access raw data.

Yes, really.

The government changes that move toward controlling the narrative are already visible. Actual raw data spreadsheets showing military and education spending were available in three clicks as recently as five years ago. Now, the raw data is buried. At the surface level, it is interpreted for us in graphs and charts. We have to dig for the raw data. In some cases, we have to submit a formal request via the Freedom of Information Act channels and hope to get a useful result someday.

118 years after a scientist presented the greenhouse gas problem, only very expensive disasters, clearly rising sea levels, public outcry, and some creative rhetoric has made the popular oral narrative of climate change shift from “Don’t be silly” to “Oh, shit. We better pay attention to this.”

Think about Al Gore on his world tour and receiving the Nobel Prize. Piggy-backed on his rhetoric of “Oh, shit” is a message about how we got to this moment by letting profit-based corporate story via political rhetoric override objective science.

It is no coincidence that at the same time this message is finally taking hold in our tribal consciousness, background attacks on funding to university research, attacks on NASA funding, and attempts to mandate “pragmatic usefulness” of federally funded research are underway.

So it goes.

The fight for the human ability to survive and thrive on this planet is about money and who tells which story to the tribes.

We fiction writers are storytellers. Whether we work with scripts, shorts, poetry, or novels, we reach deeply into the consciousness of the people who make up the tribes. We are often the first to reach into the consciousness of the tribes because we touch the youngest minds and hearts before they develop into consumers of political and corporate narrative. Because we are the shamans, the people who create the magic that forms conscience and the illusion of rational consciousness, we have a responsibility to look deeply and carefully at possible narratives that will become part of the emotional decision making that creates a future in which the planet is a place where human beings can survive and thrive.

The Sumerian shamanic leaders created the best narratives they could for their people. Their world was small and constantly threatened by famine, disease, flood, storm, and violent foreigners.

We need to do better. We can no longer afford simple, authoritarian, insular, prescriptive narratives. We can no longer afford us/them narratives. We most certainly can’t afford the profit as success narrative. It is quite literally killing us.

Our narrative about four simple variables will determine the fate of the human race. 1) We live on Earth, a closed system. 2) We currently rely on finite resources. 3) We have created competing, growth-based economies. 4) We allow unchecked population growth.

Any decision, personal or political, that does not mitigate or eliminate one of more of these four variables is tacit support for self-inflicted human genocide.

Humanity, created by god, gods, or random interactions in a chaotic system, is only an experiment in this vast universe. In modified, handed-down Sumerian terms, our god or gods loved us so much that he, she, it, or they gave us opportunity and free will. How we treat our world and, directly or indirectly, each other is entirely on us.

Tell a good story—a story that creates hope, tolerance, and survival.

-End-

Tagged: art, author, belief systems, change, Climate Change, creative process, creativity, evolution, Global Warming, shamans, The Responsibility of Writing, writing

August 19, 2015

Are Your Readers Surprised? By Cheryl Owen-Wilson

At a recent Inklings meeting—my semi-weekly writers’ group—one of the members said, “Cheryl I don’t think your protagonist tried hard enough to escape his dilemma. I knew he wasn’t going to survive.” At this particular meeting we had an out of town guest in attendance. Her rebuttal was my protagonist’s demise had actually shocked her.

You may recall words I’ve shared in previous blogs about my unfortunate inability to keep my characters alive. Try as I might, they always seem to perish and in this particular story, he dies in a most gruesome fashion. Since I value both of these author’s opinions I had a dilemma, who to surprise or who not to surprise with my ending? The guest at our meeting, who has in the past read several of my stories? Or my fellow Inkling, who has read almost every word I’ve ever written? In the end, I knew it was my story to tell, but it kept nagging at me.

It’s a question I believe we must all ask at some point in any creative career when considering our audience. Do you continue for instance, to paint only landscapes because they sell and it’s what your patrons want from you? Or do you change to abstract and hope it is as well received? In writing there is at least one genre, that of mainstream romance, where there are generally no surprises. Most romance readers don’t want to be surprised. Yes, they understand there will be struggles, but in the end they know and want the happily ever after ending.

While pondering the question of surprise in my fiction I was unsettled by the realization that it had been quite some time since I personally had been surprised by anything, in my day-to-day life. While I routinely am surprised when painting—at times the brush takes on a life of its own and in writing—don’t you just love rereading something you wrote and being surprised by your own creative words? But my routine, the flow of days at 50+ years, is fairly consistent. Yet I’ve always abhorred the word “contentment”. My family has heard from me on more than one occasion, “There will never be a rocker on the front porch for me to sit complacently in and watch days go by, one after the other.” So I had to ask myself how had the element of surprise slipped from the fabric of my days and was it being mirrored in my fiction?

Then my grandchildren—five total, ranging in age from fourteen to five—came to visit for several days. Children=Surprise. When they are around there is a surprise occurring in every moment, of every day. And when it comes to the make believe of creating story they open new worlds with an ease both miraculous to watch and lyrical to hear. As was evidenced when we played the makeup a story game while sitting around the fire-pit at night. “Once upon a time…” Each story started and was then added to by the next child and then the next, until its surprise ending. Everything is new and wondrous to these young minds and it fueled my old one with many new and surprising ideas.

Surprise: To make somebody amazed or to experience something unexpected. Isn’t that why we create story, or art of any kind?

With the element of surprise still buzzing in my being I faced my dilemma once more. Should my protagonist live or die? Alas, he must die. Perhaps I will one day give my fellow Inkling a hero who lives beyond my story, but for now I will continue to surprise my readers with the unusual means by which my characters must meet and accept their demise.

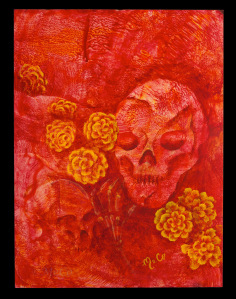

The painting below is another one of the “controlled accident” paintings I spoke of in my last blog. Imagine my surprise as I sat staring at it—at that point it was still just an abstract—and not one but two illusions of skulls appeared. I enhanced them and added marigolds and as if by magic, I now have a new Day of the Dead painting.

So what surprises are you creating?

“Day of the Dead Rising”

An Original Painting by Cheryl Owen-Wilson (MeCo)

August 12, 2015

Switching It Up

By Cynthia Ray

Part of writing a story is deciding what form it will take, or what genre. Fantasy, Science Fiction, Horror, Crime, Literary, Romance, or Non-Fiction all have different audiences and different rules.

Usually, the story itself tells you how it wants to be told. As an experiment, I once wrote the same short story over in three different genres and found that there was one way that brought out the main conflicts and themes better than others—one that made the story shine.

I’ve been thinking about this because I’m stepping out of my usual genre of short fantasy fiction, to write a non-fiction book. Yes, I said non-fiction book. This will be different for me; very different. This book won’t let me go. It had nudged me for months, and now the nudges have turned to kicks-so I had to concede.

Since it is a little scary, and a stretch for me, I decided to do some research on other authors that had switched genres to see how they fared and found some interesting facts. Many authors have successfully “switched it up”. Here are just a few:

Did you know Ian Fleming, prolific author of those iconic 007 spy novels also wrote the children’s story “Chitty-Chitty Bang Bang”? He told the story to his children and they loved it so much he wrote it down.

Roald Dahl, author of “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and “James and the Giant Peach” also wrote hard-boiled crime stories. One of his more famous stories is “Lamb to the Slaughter”, in which a woman beats her husband to death with a frozen leg of lamb, then cooks the murder weapon and serves it to the policemen who comes round to question her. Yikes!

Anne Rice, famous for her vampire novels, also wrote erotica novels early in her career, including BDSM. Apparently she was 50 shades ahead of her time.

And E.B. White, author of “Charlottes Web” wrote the writers non-fiction classic, “Elements of Style.”

Part of my fear of stepping out and starting this new project stems from a failed attempt to write a non-fiction book. A publisher of business books once asked me to write a manual on facilitating virtual meetings. As an expert on the topic, I thought it would be easy-peasey, but writing about it turned out to be dull, boring and painful.

To my chagrin, I discovered that I didn’t want to spend all day facilitating virtual meetings, and then come home and write about the process. Needless to say, I never delivered the product and took on all the inherent guilt/shame that such an experience brings.

I’ve learned from that first foray into non-fiction. Here’s how it will be different this time:

First of all, I’ve discovered something called “Creative Non-Fiction”. This genre is exactly the kind of non-fiction I want to write. Erik Larson’s book, “Devil in the White City” is a good example of this kind writing. Lee Gutkind describes Creative Non-Fiction in his magazine by the same name.

“Creative Nonfiction, defines the genre simply, succinctly, and accurately as “true stories well told.” And that, in essence, is what creative nonfiction is all about. In some ways, creative nonfiction is like jazz—it’s a rich mix of flavors, ideas, and techniques, some of which are newly invented and others as old as writing itself. Creative nonfiction can be an essay, a journal article, a research paper, a memoir, or a poem; it can be personal or not, or it can be all of these.”

Next, the topic I’ve chosen to write about is something I am passionate about (more about that later), and have a lot of fire behind. It requires research and interviews and is something interesting enough to hold my attention for the long-haul.

And finally, I have realistic expectations of the amount of work involved and what it will take to deliver the book to paper that is in my head. Right now, I’m on fire with ideas, outlines and plans. I wake up in the middle of the night with inspiration, but I know that in only a few months I’ll be knee deep in trashed drafts wondering why I started the stupid project in the first place. I can’t wait!

Tagged: change, changing genre, creative process, genre, non-fiction, starting a book, writing

August 5, 2015

Finish What You Start?

Last week I heard two friends mention that once they start reading a book, they read it to the end, no matter whether or not they like it, are interested in the characters, or find any value in it at all. One said that she committed to the end once she passed 100 pages. The other one finished the book once she started. No matter what.

While I believe their dedication is a virtue, I am exactly the opposite. There are just too many good books out there to be read. The stack on my night stand is impossible, and it doesn’t take into account all the books on my “to read some day” list. I’m not going to waste my time with a book that isn’t to my taste, or isn’t up to my level of literary scrutiny, or a book that I find distasteful.

Life’s short.

And yet… when I write something, I find it nearly impossible to abandon it, even if it has no real value to me, or anybody else.

Sometimes the things I write turn out to be mere exercises in this or that—exploring a topic, manipulating a personality quirk, toying with a relationship. They are not all meant to be expressions of literary genius.

And yet… what if I just messed with it a little more? What if I just devoted another year to it? What if I took it out of its dusty box, revisited it, and found gold?

Unlikely.

I’m now of an age where I am just starting to recognize that there are things that are destined, from word one, for the creative compost heap. That doesn’t mean there isn’t value in them for me, as a writer. They are as an artist’s sketch pad: worth exploring but not necessarily ready for the reading public.

I am breaking up with some of my half-finished novels. I have several. They aren’t working for me, and they won’t work for you, either. But it’s hard. It feels like I wasted time, even though I know in my heart that it was not. But like every relationship that needs to come to an end, there are things to reflect upon, a little gratitude for what we gleaned, and then we move on.

Writing is much like reading: there is always more out there, and there is always more in here. I’m not going to waste my time reading a book that does not thrill me, and I’m not going to waste my time writing a book that doesn’t thrill me.

This is hard.

But hey. Life’s short.

Tagged: abandonment, commitment, life's short, Novel Writing, Reading, writing

July 29, 2015

And Now, The Truth: I Don’t Like Starting New Novels

By Lisa Alber

This picture doesn’t represent my writing life.

I hereby declare that I don’t like starting new novels. What? you might be thinking. How can that be? Are you not a novelist creature? A person who loves the process, whose nature it is to gush via the written word?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. But here’s a corollary truth: Within any process there’s always that one task you can’t stand but have to do anyhow. For some novelists it might be copyediting, for others, research. For me, it’s getting into the danged first draft. I dislike it even more than the dreaded muddle in the middle.

You’d think I’d be in the infatuation period with my story right now. Everything about it ought to be bright and shiny and new and on its way to happily ever after, like, for sure.

I wish.

It’s more like I’m dangling over a precipice without a net. The other day, I realized that knowing my characters, their arcs, and the overall plot isn’t enough. There’s some indefinable something missing. I barely know what I mean by that either. It’s just a feeling that’s not in my body. A feeling of rightness even though I’ve had inklings and a-ha moments during the pre-writing development stage.

Right now my writing feels flat, uninspired. And I wonder, is that because for the first time in my life I’m writing under a strict publishing deadline?

It’s more like this.

Publishing deadlines being what they are, this novel isn’t due until a year from now. Believe me, I’ll need the whole year. I can’t procrastinate. And, more importantly, I can’t wait for the “rightness” to sail me out off the precipice on its gossamer wings.

I’m getting words down on virtual paper every day and trying to maintain faith that at some point (please, let it be within 50 pages!), I’ll feel a surge as I realize what the heart and soul of the story really is. In other words, I’m faking it a little bit right now–at least that’s what it feels like.

So what do I mean by “heart and soul of the story” anyhow? I mean the hook. Not the hook for the reader. MY hook as the writer. No one ever talks about that, but for me it’s uber-important to feel an “in” with the story, as if it’s an organic being and I need to find my way into a relationship with it. This might come about when I finally see the shape of the story in my head. Or when I understand the story’s essential truth in five words or less. Or maybe it’s about the theme. Or maybe it’s about discovering the voice for the first-person protagonist. It’s different for different writers, different stories.

There is no answer here. I’m where I am in a process, and I’ve been here before (though not exactly like this). I’ve set a rule for myself, which is 1,000 words per day. Some days it’s like climbing up prickly branches (see picture). Other days, it’s just a job; get ‘er done. Other days, it’s sheer joy.

I can bitch with the best of them, but in the end, I’ll finish my novel by the deadline.

What part of the writing process (or any process in your life) do you not like? How do you work through it?

Tagged: deadlines, novels, publishing, writing

July 22, 2015

The Agony of Empathy

By Christina Lay

I’m reading The Count de Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas and, although the heft of it makes my wrists tremble, I read anxiously and stay up late and resent any and all intrusions.

Palace of the Popes in Avignon, which has nothing to do with The Count de Monte Cristo but looks neat.

Why is this torture device disguised as a book such a time-honored classic? I quake with sympathy for the original readers who had to read this in serial form, waiting in suspense for each new installment, unaware of the conclusion. Personally, I would have headed the torch-bearing mob that stormed Dumas’ loft and demanded the immediate release of Edmond Dantes.

Do you know that innocent young Edmond Dantes gets thrown into a dudgeon and spends years and years and years locked up in darkness? Well, of course you do. Everyone does. But reading the story is so much different then watching the anime version!

I didn’t think I’d be upset by the novel since I know what happens, since the entire world knows what happens. I’m reading it because it’s one of the great enduring adventure stories of all time and I happen to be writing what I hope is an adventure and looking (always) for inspiration. The Count DMC is 1200 pages. I haven’t even read 200 yet and I am feverishly concerned with Edmond Dantes’ misfortune, waking in the night and worrying about his young life wasting away. I could never do something so horrible to one of my characters; not one I like anyway. So why, when I know perfectly well he’s unjustly imprisoned for many years, do I feel so anguished when I read it? Is Alexander Dumas that good?

I have to conclude that yes, he is. I feel Edmond’s pain. I feel the stupendous agony of youth, love and life’s promise lost. But because I know he gets out someday I can bear it. I don’t think I could read this book if I didn’t know in advance he escapes and wreaks vengeance on those who wronged him. Yikes! I’m sure there are people who could write and read a book in which Edmond never gets out, but not I. I’m too soft-hearted toward the fictional characters we bring to life with our rapt attentions. As a writer, I constantly question the why’s and wherefores of such misguided empathy. I lie awake at night, telling myself, it’s only a story! This is not real! So how is it that I, a writer, and occasionally a dastardly one who puts her characters through all sorts of torments, how is it that another writer can trick me into forgetting this?

As a reader I certainly meet a good writer half-way. Give me a character I can care for and some extreme peril, and I’m hooked. Tease me with hope and despair intricately woven, and I’ll follow you anywhere, even through how many years of horrible imprisonment? (God, don’t tell me now or I’ll have to quit reading.)

All the while I long for the payoff that makes it all worthwhile. All the while I curse the author and threaten them with psychic harm if they let me down. I think I’m safe with Dumas, which is why I dare to tread in such dangerous waters. The author who torments me in this way and then releases me to the blissful light of day, through love requited, dreams redeemed, dog saved from drowning, dork turned prom king, quest fulfilled, young lives saved, old lives blessed or vengeance wreaked, earns my eternal gratitude. Even as I curse Dumas I wonder, how can I do this?

*This post was first published on my blog Nutshells & Mosquito Wings about two years ago. It was selected by WordPress to be Freshly Pressed.

Tagged: Characters, Classic, Count de Monte Cristo, Dumas, empathy, writing

July 15, 2015

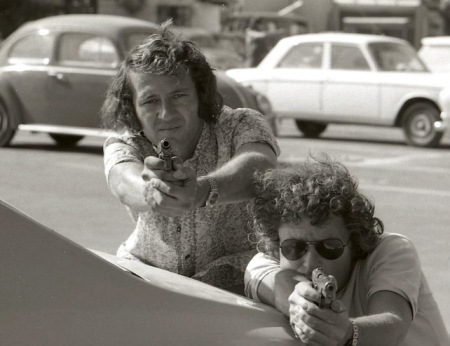

Writing Fight Scenes 3: Getting the Details Right

Photo by Yoni Hamenachem, Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

I’ve been rewatching Lost on Netflix, and once again, I’m surprised by how many writers, producers, and directors get certain details “wrong” when it comes to orchestrating their fictional violence. Much of it can be excused under the guise of serving the story (see my previous post on Graphing Fictional Violence), but some of it is just laziness or a refusal to learn how things really work.

So this brings me to my third installment on Writing Fight Scenes. I want to talk about some details frequently misrepresented in stories. As I said previously, if you’re doing something on purpose to serve a particular story, or a sense of fantasy, that’s one thing. But if you just don’t know any better, that’s another matter. We’ll take some examples from Lost since it’s on my mind.

A lot of people get knocked out in Lost, usually with a blow to the back of the head. This is a common event in a lot of action stories. I get it. It’s convenient. It gets the character out of the way for while without killing them. But while a blow to the head could knock you unconscious, these people are unconscious for a long time, like ten or twenty minutes, even hours. Then they wake up and they’re fine. The reality is, if you’re unconscious for that long, you’re looking at some brain damage and a very serious medical situation.

Likewise, a surprising number of people get beat up on Lost, and while only a few people know how to sail a boat, hunt a boar, or fix a radio, almost everyone can throw a wicked right hook. To their credit, it makes sense for a few of the characters, and they go to some pains to establish an explanation for others. But you see this in a lot of stories, as if boxing were a universal sport. The truth is, I know a few martial artists and not even all of them are good at punching. Most people have a strong psychological aversion to really punching someone, and it’s definitely not a ubiquitous skill.

And now for the guns! There are a lot of guns in Lost, and who controls them, and uses them, rightly or wrongly, is a big topic. Use of firearms, like punching, is not a universal skill. Lost does a pretty good job with establishing this and why some characters have this skill and others don’t. Where they go wrong, and where so many stories go wrong, is in the details. The biggest offender these days is in the constant slide racking of automatic pistols. It’s dramatic. It’s a sound that gets your attention. Sure, but in most cases you’re just wasting valuable ammunition. The slide needs to be racked to load the first round into the chamber. This is usually done when the weapon is loaded. After that, manually racking the slide would just eject an unfired round.

The other mistake with guns is characters who should know better walking around with their fingers resting on the triggers. But I’ll leave it for another day, along with reloading.

Finally, I have to add, I have it on good authority that shocking somebody who has flatlined will not revive them. CPR is good, but forget about the paddles. Those are used for reestablishing a normal cardiac rhythm in cases of life threatening dysrhythmias and ventricular fibrillation. Once the heart stops you have other problems.

So what do you do? Do your homework. Educate yourself on the technical aspects of a scene. If you want a character to be unconscious for a long time, but you need them alive later, maybe a drug could work. If a character is an awesome fighter, consider establishing why. If you hand a gun savvy character a gun before battle, have them check that it’s loaded, but not rack the slide with abandon. If you’re going to show somebody flatline on the operating table, find out what a surgeon would really do. If you still want to ignore reality after you’ve figured it out, at least you’re doing so consciously, and presumably with good reasons.

July 8, 2015

Uniquely Normal is not Broken: My Best Brain Hack, by Eric Witchey

Photo by Stefano Tinti. Licensed through iStockPhoto

Uniquely Normal is not Broken: My Best Brain Hack

Eric Witchey

We live in a one-size fits all self-help culture. If we buy into the belief that we are broken that underlies almost all self-help books and movements, then the fundamental message tends to be the same. To fix yourself, you have to really want to change! Then, there’s the list of things you should change and how you should change them. Currently, the old religious ideal of faith, which often meant trust us to tell you what to think and don’t ask questions we can’t answer, has been replaced with manifest abundance by believing completely. If we fail, we must not have believed completely enough. If we can’t make the self-help system work, shame on us. We need more discipline. We need more energy. We need more education. We need more empathy. We need more… We are broken.

Yeah. Okay. Let’s just start with the understanding that I am broken. If I’m broken, then I’m like everyone else. That means I’m not broken. I’m uniquely normal. I’m good with that.

This week, broken me lost track of time because I was busy teaching a corporate class, writing fiction, doing book production, and being very disciplined about writing fiction and distance skating every day. On top of that, one of my editors sent back her recommendations for a table of contents for a collection of my stories. That caused a minor upswing in mood that created a break in my productivity due to wine and good food. Then, an amazing artist and writer, Alan M. Clark, sent me the first peek at the cover art for my novel, Bull’s Labyrinth, which will finally come out soonish.

While I was distracted by wallowing in my bliss, Monday suddenly jumped out of the temporal bushes, and my automated calendar sent me a reminder that I had a Wednesday deadline for a blog I hadn’t even thought about.

I needed a topic now!

Solution?

Human experiments on my friends!

I asked my friends on FaceBook what they wanted to read about this week.

My friends were great. They participated fully in my experiment. They responded with a good, solid list of topics interesting to writers. Several topics were even things I was interested in doing. In fact, I will get to all of the items on the list in later blogs. However, I chose brain hacks for writers for this week’s offering.

Well, that should be easy, I told myself. Just write a listicle of how-to production techniques. You know the kind of thing: “Five Things Every Writer Should Do before Breakfast.”

Unfortunately, the first attempt turned into an overly long description of the chemical relationship between L-dopa and dopamine and how dopamine levels influence the thought-to-action brain-body connection. Having no dopamine doesn’t stop you from being conscious, but it does result in being trapped in a motionless meat puppet. Watch Robert DeNiro and Robin Williams in their 1990 film, Awakenings. Great film, but I’ll warn you that it is not at all funny.

So, blog attempt #1 sucked. Nobody wants to hear about brain chemistry, organism adaptation to task, and how to build up that connection. Also, being conscious and trapped inside your body is a better topic for a story than a blog.

What people were really asking me for is a solution to their problems. At least, that’s what I told myself.

So, attempt #2 waxed philosophical about free will and how to reduce complex problems to smaller, more manageable problems then prioritize them into action steps.

Oh, just bullshit. Seriously, who doesn’t know that? Does it work? Sometimes. If it always worked, the self-help industry would just die. Think about it. If everyone who knows that trick actually succeeded in connecting their desires to their actions, who would buy a second self-help book or attend a second self-help seminar? Oprah, Dr. Oz, and Dr. Phil would be right out of business. Well, maybe not Oprah. She has a little more emotional depth and breadth of vision.

If you want procedural, emotional and self-discipline type self-help thinking, I recommend a combination of Julia Cameron and Stephen R. Covey. I do, heartily, recommend both rather than one or the other. Both have wonderful, valuable insights. Some might be useful to you. Some have been useful to me, but I don’t need to repeat what they have done.

Now, here I am in attempt #3. Brain hacks for writers. Yeah. Okay. Except, there’s a problem. You see, I don’t buy into the one-size-fits all self-help world. I’m more of a my-size-fits-me sort of guy.

You see, after 30 years of studying how writers write and how readers interpret the little black squiggles on the white background, I have come to the experimentally verified conclusion that my brain and yours are different.

I know. It’s stunning, isn’t it?

Worse than that, my life and yours are different.

Can you believe it? I mean, it actually turns out that based on their personal experience both Republican and Democrat pundits actually believe the stuff they say when they say it.

Similarly, if you face the blank page and your gut goes to jelly, you want to puke, and you end up cleaning the kitchen, you and I have something in common. However, the thing we have in common is neither cognitive physiology nor nurture trauma. In other words, my body is reacting to the fact that my brother liked to belittle me by creating sometimes elaborate scenarios in which he publicly humiliated me. You, on the other hand, may have attended a parochial school where writing was a punishment. While your body and mine are reacting the same way to the potential rejection and humiliation of failure on the page, we won’t respond to the same brain hack solutions.

In fact, some people’s experiences have caused them to need to write in order to prove they are better than other people. Some have adapted to the need to write in order to clarify their thoughts. Some need to write in order to get attention. Some need to write… and it goes on and on. It is unlikely that you and I write for exactly the same reasons or to fulfill the same needs in our lives.

Why do you need to write?

I have not one single clue.

However, I can say that my writing life turned a corner for the better after I was diagnosed with dysthymia with components of OCD. I won’t go into the physiology of my “disorder.” I’ll just say that the DSM diagnosis is a description of a set of symptoms rather than the actual physical underpinnings of that set of symptoms.

The important thing for brain hacking is that once I was diagnosed, I was able to begin exploring what was different about my brain from other brains. For example, I learned I also had dyslexia, for which I had found elaborate compensatory skills. Who knew I couldn’t do math in grade school because the numbers jumped around? Nobody ever tested me. I also learned that the ADHD I had been treated for as a child was considered a precursor to the problems I had as an adult. I learned that my addictions became a compulsion because of a need to medicate away pain. They became an obsession as a result of low dopamine. I learned the hard way that no amount of NA philosophy or community would change my physiology to allow me to be able to physically follow through on the choice to actually attend NA meetings on a regular basis (You just need to discipline yourself to attend. Call your sponsor. Give it over to your higher power.). You see, that advice could only work if I were physiologically capable of transferring my desire into the action of picking up the phone or going to the meeting. At the time, I couldn’t do that. Giving me that advice was, physiologically speaking, exactly the same as telling a quadriplegic they needed to choose to get up from their wheelchair and run. They can believe. They can want it with all their heart. They can try, but they are not going to run.

No, I’m not kidding or joking.

So, my recovery route was, initially, dependent on doctors and medication. Eventually, and with much hard work under the influence of good doctors and medication, the drugs were replaced by ten years of self-observation and supporting therapy that was specific to my brain.

It worked. I’ve been recreational drug-free for 25 years, and most days I manage my brain. A few weeks ago, I sold my 100th story. Not bad for a problem child, recovering addict.

Why do I put these things in my blog on brain hacks for writers? I put them here to show how uniquely normal I am and because the best brain hack I know I learned while in therapy. It has given me all my other brain hacks. It’s called meditation.

Read Jon Kabat-Zinn. His mindfulness movement does not begin with the idea that his readers are broken. He begins with the idea that only the reader can decide what the reader needs, and that comes from learning to sit still and pay attention to ourselves.

I’m not talking about our writer’s endless narrative of self-criticism.

My internal narrative goes like this on bad days, “Oh, for the f of J, Eric, pull your head out of your ass and get to work. Well, shit, here you are cleaning the damn oven. It could have been dirty for another day or even another six months. Just stop it. You should be working on that effing novella. Come on! What kind of wimp are you that you can’t even put down a sponge, turn, around and walk upstairs to put just one damn line on the page?”

This kind of thing can go on for hours and hours, sapping the joy out of everything I do because I’m not doing the thing I should be doing.

What a terrible word—should.

And, my friends, this is what drives the “you are broken” self-help industry. Call it guilt. Call it shame. Call it original sin. Call it whatever you want, but should is the filler of guru pockets and the killer of creativity.

So, if my brain/body experience is unique to me, how do I overcome the unique obstacles created by my brain?

Inventory. That’s pretty much my only real writer’s brain hack.

I pay attention to what I am doing instead of what I should be doing. I know what I want to do. I know what I want my quota to be. I know what my annual, monthly, weekly, and daily goals are. All of that is well and good, but if my stress goes up, my dopamine goes down. The more down it goes, the less likely I am to do anything that corresponds to my own thoughts and desires. The more I get into the should cycle, the more stress I create and the worse my control becomes—less directed action leads to more shoulding leads to less directed action. Beating myself up will only make it worse. When it gets really bad, I can end up playing obsessive hours, and occasionally days, of some computer game in order to escape from my own looping, self-destructive thoughts.

Eventually, I return my focus to my breath. I meditate.

That’s the simplest, most powerful brain hack I know. If I can, and I can’t always, and that’s fine, I stop and pay attention to my breathing—to the feel of my diaphragm shifting and stretching and contracting to move air in and out of my chest. I focus my mind on that simple, life-giving thing, and I let whatever thoughts come to mind come to mind. I acknowledge them and the emotions that drive them, and I let them go and return my focus to my breath.

Out of this one simple exercise has come many moments of understanding about how the metal-edged ruler of my childhood grade school classes influenced my love of and resistance to writing, about how my brother’s behavior influenced my need to hide from potential humiliating experiences by not writing, about how my mother’s attempt to run off to marry a priest influenced my behavior, about how and why some topics come quickly and others don’t, about my relationship to story, about my relationship to my sense of self and my place in culture and human history, about….

Yes, this is a simple exercise. It is, at its heart, Zen meditation. It is not in any way about emptying the mind. It is about focusing on the breathing. We have to breathe anyway, so we always have the tools we need with us. We simply will not, at least under any circumstances we survive, stop breathing. So, just pay attention to the breath. Focus on the diaphragm’s movement and the flow of air. Just let the thoughts that come to mind come. Note that the thoughts are there then return the focus to the breath.

That’s the whole thing. That’s the hack. Nothing else. It’s not about forcing the focus. It’s not about emptying the mind of thought. It’s not about making something happen. It’s just about paying attention to the breath, acknowledging the inevitable thoughts that shift our focus away from the breath, and returning our focus to the breath.

Sometimes, I can just take a few breaths and instantly overcome whatever limitation faces me. Sometimes, the reasons for my own limitations come in bits and pieces over years. That kind of self-discovery and understanding can’t be forced. All we can do is pay attention and repeat the practice over and over and over. We can do it walking, riding a bike, eating, playing an instrument, or while doing pretty much anything we do. It really is that simple. If it gets complicated, we’ve made it complicated, and that’s something to acknowledge before returning to the breath. We can forget to pay attention for days, weeks, or years. Then, when we remember again, the breath is there. We can just pick up again where we left off.

So, my diagnosis set me on the path of self-observation. After my initial experiences with more intrusive medications, my self-management practice stabilized into meditation and methylphenidate (Ritalin). I take the drug as little as possible, but I have found my breath while fishing, while running, while biking, while skating, while driving, while sitting in an easy chair, and while laying on my back in a room full of meditating people. My breath is always with me. I have made a habit of never leaving home without it.

From this one, simple practice, I have discovered that, for me and only for me, I can celebrate success if I practice fiction for five minutes a day. If I do five minutes of conscious practice each day, I win! I am always allowed to do more, but my daily success comes from sitting down and practicing some technique for five minutes.

You see, my obstacles have always manifested themselves on the way to putting my butt in the chair and beginning to type. Once I start typing, I’m fine.

I built my brain hack to match my issues. I discovered that I have very specific performance anxiety triggers. I found them. I built my hack so that I’m not performing. I’m only practicing. Sitting happens. Typing happens. Breathing happens. I’m also still discovering layers of triggers. The discovery doesn’t stop even if we design a hack that works.

What do I practice? Any technique I can describe and execute. I have dozens of how-to books to pick skills from. I keep my own running list of techniques I need to practice. I keep a list of random prompts. I pick one technique and three random prompts. I write for five minutes, trying to get the prompts into a story that demonstrates the technique. I don’t plan to succeed. In fact, I plan to have fun failing. However, my practice of returning to technique basics and having fun has resulted in stories that account for at least 50 of my sales. Of course, as soon as I start thinking of the practice as a story, it stops being a practice. Then, I need a new set of personal hacks. Those hacks are a topic for another post.

So it goes. Oh, the silly ways our brains sabotage us. . .

Other brain hacks include writing with other writers around me. Sometimes, changing locations is the trick. If I observe that the kitchen is getting wear marks on the counter because I’m cleaning it too often (I wish), then it’s time to go and write someplace where there is no kitchen to clean. My local city library has quiet rooms. Several of my local coffee shops have first-come-first-served conference rooms.

If I observe myself surfing the web for hours and hours, I go to a wifi free zone and shift to pen and paper for a while.

If I find I am bored with my own writing, I find another writer (or creative non-writer) to talk to about creative effort.

My absolute favorite people are the ones that can riff silly on any topic. Stories are often born from silly. My chosen brother Mitch Luckett, my biological brother, Nick, and another chosen brother, artist and writer Alan M. Clark, are great for that. Another chosen brother, Barry Buchannan, who is an infrastructure systems analyst, is also refreshingly good at it. Something new and fun always comes from conversations with these people. I go to my sister, Leonore, for wonderful, fun, imaginative explorations of body, mind, and spirit. I guess the short version of this hack is to go out, smile, be silly, and talk to people who have agile minds and a good sense of humor. Let the child within out to play.

As one friend of mine, Devon Monk, once told me, “It’s very important to get out and ride an elephant now and then.” New experiences feed the fire of heart and mind. Personally, I find that travel opens up my channels of creative energy. While travelling, abroad or just to the grocery store, I keep running lists of things I see, hear, smell, feel, taste, and consider. I especially keep lists of things that trigger emotional responses.

In fact, I have running lists of “Things that make me cry from joy,” “Things that make me laugh out loud,” “Things that make me tear up from sadness,” and “Things that make me wish for…”

You get the idea.

In the end, all these brain hacks, from getting up early and going straight to the keys before my dreaming mind has submerged to setting dead minimum time quotas that aren’t about quality or page and word counts, have come one-by-one from returning to my breath—my breath.

I cannot, and will never be able to, gain the correct and complete insight into your personal genetics, family history, physiological reactivity, and complex self-protections that will allow me to diagnose cause and prescribe management skills. Only you can do that for yourself. Even a really good therapist will only facilitate your discovery of your own needs and skills, so I do have to say that I really appreciate the good therapists I have known.

So, pay attention and engage in constant, restless, ceaseless human experimentation on you. I will be there beside you, at least in spirit, celebrating your realizations and the hacks you create for yourself, but I will have no expectation that your hacks and mine will match up. Even if they do match in form and execution, it is very likely that they work for us each in very different ways for very different reasons.

We are not broken. We are a complex manifestation of a biological, and perhaps spiritual, experiment that began billions of years ago. We are exactly what we should be. We are exactly where we should be. We are story tellers. Tell a story. That’s all we need to do. That, and breathe.

Now, I let these thoughts go and return my focus to my breath.

-End-

Tagged: author, belief systems, brain hacks, creative process, creativity, editing, Elizabeth Engstrom, Emotion, Eric M. Witchey, Eric Witchey, evolution, fantasy, fear, fiction, genre, meditation, personal hack, self help

Shared ShadowSpinners Blog

- Eric Witchey's profile

- 51 followers