Eric Witchey's Blog: Shared ShadowSpinners Blog , page 21

August 17, 2016

How Do I Pitch MY Genre? by Eric Witchey

How Do I Pitch My Genre? by Eric Witchey

After teaching a class, volunteering to help Timberline Review sell subscriptions, and signing my newly launched novel at this year’s Willamette Writer’s Conference, I was walking along a hallway minding my own business and wondering if I could get back to my room to take a nap before I had to face another room full of 100 people. A personable guy said hi and caught my attention. He was a volunteer gate keeper outside the pitch and critique room where aspirants bring their hearts and souls for fine tuning before presenting them in ten minute chunks to agents and editors looking for commodities from which to make a living. Making eye contact, I became aware of my surroundings and realized that the room was understaffed and several people were waiting for a chance to get what might be critical advice. So, I volunteered to take a few pitches and help hone them.

Mind you, there’s actually plenty of help for this kind of thing. The conference ran pitch practice sessions before the conference. They ran pitch practice sessions at the conference. Most of the people pitching had practiced with friends, family, and crit groups. And, as a last chance for final revision and preparation, the conference had a pitch practice room, into which I walked.

I sat down, and the kind people at the conference showed four nervous writers my way—one at a time. I had fifteen minutes to help each.

The four writers had been coached to provide half-page synoptic summaries of their books, and each showed up with pages that did that. The idea, as I understood it, was to give a sense of genre, of character, of content, and of market potential.

Well, that list seems pretty obvious to most people. After all, a science fiction adventure isn’t the same as a historical romance, right?

Wrong.

What was not so obvious is that these people were terrified and clinging to every bit of advice they had ever been given in the hope that it would touch the hearts of jaded professionals and give up a result that would change the writers’ lives and let them connect their hearts through their words to the world.

Can you say, “TERRIFIED?”

One had a fantasy romance. One had a historical novel. One had a non-fiction book on how to talk to kids about sex. One had a cryptobiography. All had decent concepts that could fly in the market. Mind you, I hadn’t read the stories themselves. I only had access to a few pages of pitches and the problems the writers had encountered in trying to sell their stories.

So, we got to work.

In three of the four cases, I realized I didn’t have much to add to the long-form pitches the writers had honed. However, I did have the communication consultant skills and personal experience of 25 years of freelance work. So, I gave all three exactly the same thing.

Emotion.

Twenty years ago, in 1996, I pitched my first novel—a novel that later sold in Poland, but that’s another story. While practicing with my good friend Gail McNally (no, not the actress), I was proud of what I had done and of the fact that I had memorized my pitches cold. Gail listened kindly—eyes closed, nodding, pinching her nose. When I was done, she said, “That might work if you put the emotion in.”

Huh? Obviously, she had missed something because I knew it was a brilliant pitch. After all, I had read about pitching. I had talked to other people. I had carefully crafted my pitch. I had a 30 second pitch, a three-minute pitch, a full page pitch, a five-page synoptic outline, and a full synoptic outline. I was freaking loaded for literary bear.

What the hell does emotion have to do with selling the product?

So, long story short, I lost the argument and rewrote it all with an emphasis on character emotional change.

My first time pitch nailed an editor and let me choose between several interested agents.

Why? I now know it was because stories are not about things or events. Stories are about how people change emotionally and psychologically. Things and events only facilitate the changes.

Yes…. The things and events have to be “interesting and unique,” but they are only truly interesting in that they are connected to emotional change.

So, I helped each one of my three fiction charges fashion a one- or two-line pitch that captured the three Cs:

Character, Conflict, and Change.

You could say it is really only two Cs because Character is really made up of an emotional/psychological state, and Change is really just the character as they appear after they change because of the conflict. So, really, it’s just Character, Conflict, and Character, but that’s a bit confusing and doesn’t really sound right in a culture that likes to think in threes.

Essentially, we put our heads together and came up with statements like:

Soul and psyche torn down to nothing by the murder of her family, outcast 1940’s gay homemaker Millicent Monroe faces insurgent Nazis in the Iowa farmlands and consequently discovers deep connection to the community, land, and country that persecuted her.

Okay, that’s not really one of them, but maybe I’ll write that book. We’ll see.

Anyway, three of the four walked away with a similar statement and some communication consulting advice about how to speak, how to make eye contact, when to pause, and how to manage the transition to their larger already prepared pitch.

One, however, didn’t. That one makes the other three all the more interesting. The fourth person had career as a sex education lecturer, consultant, and therapist. She had a values-neutral book about how to talk to kids about sex. Her problem was also emotion, but it wasn’t the emotion of the book and characters. Her problem was that every time she pitched the book, people’s “sex stuff” came up and interfered with their ability to see the product she offered. Her problem was that she needed to disarm her audience’s emotions in order to allow them to look at her work.

That was interesting, so we worked the same problem from the opposite direction and provided her with language that identified her platform and established a context in which the content created result for the readers who bought the book. We brainstormed keywords that would frame the conversation in terms of platform, product, and market. I also recommended that she add an additional agent I knew to her pitch list.

Results?

Over the following couple of days, one-by-one, each of the four sought me out to share their excitement and success. Each one hit—and not just once. They all got requests from every agent and editor they pitched. All of them.

Why?

Here’s the bit that isn’t as obvious. These writers had been prepared by professionals to walk in and deliver fairly lengthy pitches that made use of the time available—ten minutes. Those pitches might have done fine by themselves without my help. However, agents and editors don’t take pitches in order to hear the story that takes a book-length manuscript to tell. The take pitches to filter the masses through sieve in order to find the writers who control character and story. If a writer truly controls the craft of presenting character and story, then the writer can state character, core conflict, and change succinctly.

Conversely, if a writer can state character, core conflict, and change succinctly, it is likely that they control craft well enough to deliver story. When a writer succinctly states the emotional core of character, the conflict that changes them, and the new emotional makeup of the character, agents and editors hear much more than is stated. The result is that they sit up, quite literally, and start to ask questions that can only be answered by reading the manuscript. So, the pitch creates a conversation that leads to a request for pages.

In the unique case of the non-fiction writer, the emotionally charged material wasn’t the problem. The problem was to help people see the product rather than let their emotional response to product become the primary experience of their encounter. It is really a mirror image of the same problem.

But it’s different for different genres, right?

Nope. Genre doesn’t matter on the heart and story level. Never has. Never will. Genre is marketing category. Yes, you don’t pitch space opera to a commercial woman’s fiction editor. Don’t be entirely daft. However, genre isn’t story. Genre is only a taxonomic label for expectations concerning things and events. Sometimes, genre influences the mix of techniques used for telling a story, but genre has nothing to do with heart and soul and hopes and dreams. The story comes from the writer’s heart and seeks to touch the reader’s heart. Pitching is about letting a potential buyer know that the writer understands heart and controls story craft well enough to deliver emotion to the reader.

-End-

Tagged: author, Characters, creative process, creativity, fantasy, fear, fiction, genre, horror, inspiration, Novel Writing, novels, pitches, pitching, Psychology, writer, writers, writing, Writing conferences, writing habits

August 11, 2016

Finding Your Voice Through The Chatter

By Cheryl Owen-Wilson

What is Voice, and how does it inform your creative life?

Is it just the sound emanating from your throat as your words bounce along your vocal cords? Or is it the tape loop of non-stop chatter playing in your brain? The chatter more commonly known as your monkey brain, since it generally swings from one topic to the next—yes, that paragraph is perfect for the beginning chapter—to just a few minutes later—what were you thinking, no one will read past this paragraph if you start the story there. And with all the noise of your monkey brain how do you even begin to find your—Voice?

Voice—such a small word for such a large topic when discussing creativity. Because ultimately we creative folk would love it if the world at large wanted, no not just wanted, but craved to read the stories we’ve written. Stories created by our own uniquely filtered—Voice.

The monkey brain I discussed earlier, has reminded me on more than one occasion of the old saying—Everything has already been written, every story already told. If that is true, why do I continue to write? Why, because eventually my monkey brain swings back and reminds me of those unique filters only my, Voice can create..

My time in history, I am a witness and recorder of this moment. No one else will live it, see it or record it in the same way, as I will. It is filtered through my life experiences, my traditions, beliefs and feelings and even if I’m not writing current day fiction, those filters still apply when I delve into past history.

The old adage—write what you know—well, I know about being a mother to eight children—seven of them girls. Combine that fact, with growing up in a matriarchal family and you will understand why most of my stories center around the relationships of mothers and daughters.

My own rhythm. In music, you can have three different people sing or compose the exact same song; however, when you hear it, it will sound different with each new player or singer. This is also true in writing. There is a cadence to each individual’s writing, their own rhythm, as they string words together to paint a picture in the readers mind. My writing has the slow rhythm of the Deep South of Louisiana since that is where I grew up. Another writer growing up in a large city would more than likely have a different cadence to their stories.

I’ve spoken to many writers and painters over the years and I often hear, “When I found my Voice, everything fell into place.” Unfortunately we live in a mainstream educational society, which might attempt to silence your distinctive Voice before it is ever fully developed or heard. They may cover it with grammatical rules and years of societal norms of what your writing should or should not be. Some have even been encouraged to pursue other careers by well meaning scholars, because their writing was too radical, too outside the box. Please never let your Voice be silenced in this manner.

I encourage you to continually seek out your own exclusive Voice. But remember, just as we evolve and change through time, so might your Voice. So listen to it closely and when your monkey brain intrudes, enjoy swinging from vine to vine. Because it can take you to many amazing places, if you just sit still and let your Voice shine through all its chatter.

Tagged: art, creative process, creativity, Voice, writing

August 4, 2016

Lying Fallow, Going Wild and Writing in the Nude

By Cynthia Ray

Last week in her post, Liz talked about her literary compost pile. It is summer, after all, so I was inspired to continue with the gardening theme. The principles of fallowness and wildness can be applied to our creative lives.

Before the advent of chemical fertilizers, farmers would rotate crops to balance the nutrients in the soil, leaving some fields fallow for a season. Leaving fields fallow meant that nothing was planted there for the entire growing season. This allowed the soil to rebuild itself, and rest. This thousands of year old process continues to this day in many parts of the world, because it works.

Just doing nothing can be incredibly valuable. Have you ever tried to do nothing? No TV, no book, no writing, just sitting and doing nothing? It’s an under-utilized non-activity. It is not even trying to be “mindful”. It is just being. How long can you do nothing? Fallowness, for me also meant taking a break from plowing the same old fields over and over again. I had to give up some non-productive, obsessive habits that depleted my creativity and time.

Giving up my habit of editing my manuscript before I had even got to the end of the first page, stopping at the first paragraph and going back over every word. I forced myself to just leave it be, and keep writing. Not an easy task but a freeing one. It also meant for me to take more breaks, walk in the woods, dig in the yard and then come back to my project renewed. Tearing myself away from a computer screen and immersing myself in nature is how I re-charge and give my brain a break.

Another version of this ‘leave it be’ approach requires letting a portion of your yard or garden go to seed, creating a non-domesticated space. This small wild area enables natural ecosystems to develop, attracting butterflies, birds and other creatures to abide there. It can replenish and rejuvenate the soil/soul.

Letting ourselves be non-domesticated for a while, allows the wild to show its face. How could I be a bit wild? I experimented with writing in the nude. I thought it would be a way to symbollicaly drop pretense, and get to the heart of things. Later, I found out that this is not uncommon. A web search turned up several authors that used the technique:

When Victor Hugo, the famous author of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, ran into a writer’s block, he concocted a unique scheme to force himself to write: he had his servant take all of his clothes away for the day and leave his own nude self with only pen and paper, so he’d have nothing to do but sit down and write.

DH Lawrence [who wrote the controversial (and censored) erotic book Lady Chatterley’s Lover, liked to climb mulberry trees, in the nude, before coming down to write.

Ernest Hemingway did not only write A Farewell to Arms, he also said farewell to clothes! Hemingway wrote nude, standing up, with his typewriter about waist level.

Benjamin Franklin also liked to take “air baths,” where he sit around naked in a cold room for an hour or so while he wrote.

Mystery writer Agatha Christie liked to write anywhere, including in the bathtub!

So drop those habits along with your clothes, sit around and do nothing for awhile and enjoy the rest of the summer!

Tagged: craft of writing, Creative compost, creative process, creativity

July 27, 2016

The Creative Compost File – or Where do You Get Your Ideas?

One of the most valuable items at my desk is in my file drawer. It is a folder entitled “Creative Compost.” This is my gold mine and it is thick with odds and ends.

When I’m doing my daily ten-minute keep-the-pen-moving practice exercises, and I happen onto something tasty, at the end of the ten minute exercise, I rewrite the good idea, or the good passage, and slip it into the compost file. When I have an unusual dream, or meet someone with a great name, or hear a story that could evolve into wonderful fiction, or encounter someone with a distinctive speech pattern, I waste no time in writing it down and putting it into my compost file. A song lyric. A weird news item. The intriguing juxtaposition of words. A spiritual concept presented by a friend. Any number of things that captivate, confound or amuse me find a home in that file.

Do I ever refer to it? No. Just like I never refer to the coffee grounds, once they’re thrown into the garden compost pile in my back yard. I just leave them there to work.

And work they do.

I have come to believe that it is the act of cutting the item out, or writing it down and putting it into the compost file that cements it in my mind. Just like the elusive dream that evaporates before noon unless I relate it to someone or write it down, so does the Great Idea unless I actively do something with it. Or like the discarded banana peel—it isn’t much all by itself. But throw it onto the soil, rich with micro-organisms, the roots of a nearby rosebush to encourage the decomposition, and hungry worms to digest it properly, and voila! That old banana peel becomes something worthwhile.

And so it is with the bits and pieces within my file folder. It adds to the fertility of the mind. It combines its nutrients with others in the mental digestive process. Just like the backyard stuff, good stories stem from a combination of nutrients. It is the blending of character, setting, and conflict. What comes out of the compost pile is pure gold for the garden and what comes out of the compost file is pure gold for my writing.

I went through my compost file about two years ago for the first time in maybe ten years, because it had become so thick it was taking over my file drawer, and discovered that I had used probably eighty percent of the things in it. I cleaned it out and began again.

That was a simple act of turning the compost. I’ll do it a little more often now, but not too often. Some of those ideas are kind of woody and fibrous and need time to break down and blend in.

So I just keep on adding to that file and keep my trust in the process.

Tagged: compost, Creative compost, creative process, creativity, daily writing exercises, inspiration, writing, writing habits

July 20, 2016

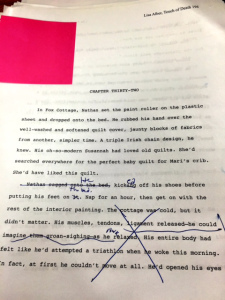

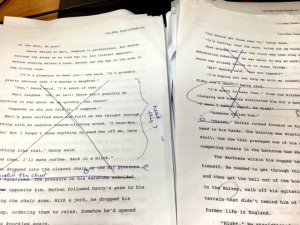

The Art of the Overwritten First Draft

By Lisa Alber

By Lisa Alber

I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m the master of writing bloated first drafts. I like to tell myself that it’s all for a larger cause. There’s a saying attributed to everyone from Ray Bradbury to Robert Heinlein to Elmore Leonard that it takes a millions written words to become a competent writer. If this is true, then I must have hit the magic number by now.

And so …

I’m here to tell you that you, too, can become a competent writer just like me!

Want to hit your million words toward competency? Yeah? Then do what I do! Write morbidly obese first drafts. Savor all those words marching their way across the page toward your mastery. Delight in the fact that whereas other writers underwrite their first drafts, by the time you complete yours you will have so much to work with you won’t know where to begin. Imagine the thrill of deleting whole paragraphs, pages, and sometimes scenes!

It’s fun. Join me! Enjoy the thrill of puffy, self-indulgent, sometimes melodramatic drafting! To help you on your quest toward the magic million, I give you my tips and tricks for overwriting your first drafts:

To help you on your quest toward the magic million, I give you my tips and tricks for overwriting your first drafts:

Do it like a kindergartner: Don’t just show when you can show and tell. That’s right, go ahead and let the character expound on his plan for trapping the bad guy before you have him actually do it. Never mind that this spoils the suspense, bring it on!

Don’t use one sentence to describe how a character feels when you can have her endlessly obsess about how everything bad in her life comes down to her mother. When in doubt, over-analyze!

Do hit the reader over the head with the same point about your character’s traumatized past in 50 different ways, with each way more eloquent and poetic and beautiful than the last.

Do add extraneous subplots that go nowhere but showcase your wondrous talent with “quiet moments.”

Don’t forget long-winded metaphors triggered by weather. Ripping winds and lashing rains are especially useful for sinking into the descriptive abyss.

Do use every moment in every scene to show everything. Don’t let a chance slip past when you can expand a simpl

e narrative statement into a full-blow Moment. Yes, capitalized.

e narrative statement into a full-blow Moment. Yes, capitalized.Don’t forget to have your characters over-react, thus inciting pages and pages of scrumptious dialog.

Do use the same delicious words over and over on the same page. Words such as “scrabbled” and “molten” are fun — make them bleed on the page!

Throw a party! It’s never too late to invite more characters into the story even when they don’t forward the plot. I bet they’re the ones with the wittiest one-liners!

Last but not least, do it like I do and blindly feel your way through the plot, digging into those false starts and trying-to-find-themselves scenes. Munge on, my friends, munge on!

Stay tuned, next time I’ll be bringing you “Self-Tortured Revision for Dummies,” in which you too can detest everything about your so-called competency as you polish a 500-page white beast from hell into submission.

Tagged: first drafts, humor, Novel Writing, revision

July 13, 2016

What I Learned About Plot by Watching Orphan Black

by Christina Lay

This post is a direct rip-off of Liz Engstrom’s post about the characters in Downton Abbey. But it’s also true I’ve been having this conversation with myself for a while now, an internal discussion inspired by my love/hate relationship with this near future SF TV series. I watched the first three seasons over the course of a few months and a couple times when I turned off my Kindle, I thought I wouldn’t be going back, but I couldn’t resist. Naturally as a writer when I experience both exasperation and fascination, I have to question what’s going on and how the writers have managed to piss me off and hook me in at the same time.

If you haven’t watched the show, this is a British series about clones. Yes, clones. The big secret revealed in the first episode is that the main character, Sarah Manning, is a clone. She meets several of her “sisters”, along the way, all with wildly different personalities, all played by the absolutely amazing Tatiana Maslany.

Sarah, stuck between a hard place and another hard place, as usual.

We have Sarah, the street-tough Brit with a heart of gold, Beth the cop who’s identity she steals in the first show, Alison the suburban soccer mom, Cosima the nerdy scientist, Helena the psychopathic Ukrainian nut job, Rachel the evil director of an evil corporation, and so on. The best character in the series, in my opinion, is Sarah’s brother Felix, the smart-alec gay artist who is Sarah’s rock, although she constantly ignores his sensible warnings.

All great fodder for a wild SF thriller. So how did this series hook me?

Great acting. For a writer, this can translate into great character development and dialogue. In other words, how convincingly we portray our characters on the page.

The characters are working toward a solution, finding answers, taking the bull by the horns, etc. They aren’t sitting back waiting to be victimized. Being clones is out of their control, but they never stop fighting back against the Evil Corp that would destroy them.

Constant, exciting forward motion of the plot. This can easily be overdone but Orphan Black manages it well, alternating the life-or-death situations with down time for deepening relationships between the characters— just a breather right before they get shoved off the next cliff.

Good guys win more of the battles. This is a big one for me. I have a low tolerance for grim, unrelenting BADNESS just for the sake of being grim and bad. While the “war” continues to expand, with more bigger and badder bad guys always crawling out of the woodwork, the immediate LOD situations Sarah finds herself in are usually resolved in a satisfying, aren’t we all relieved she survived/escaped/rescued the kitten etc. sort of way.

Plenty of humor and a sense that the writers are aware there is a ridiculous side to this story.

Not overdoing the Next Worst Thing. There’s a rule in writing that states in order to keep the conflict and tension building, you should ask yourself what’s the worst thing that could happen to your character and then make it so. Again, easily overdone. I for one get tired of brutality and misery pretty darn quick. Orphan Black definitely has a dark edge and bad things happen, but the hook for me is that although the ‘worst thing’ often looms as a threat, it usually doesn’t happen. This is a big relief to me as a viewer.

So how did this series piss me off?

Relentless stupid character syndrome. Making bad decisions over and over. True, these decisions are often what forwards the plot, but I really wanted Sarah to get smarter. There is only so often you can throw yourself against Evil Corp with no plan other than to wave a gun around, get caught, get saved and then do it all over again.

Overuse of the Big Coincidence. To the point of eye-rolling and mockery. And it wasn’t even new coincidences, but the same old one used in nearly every episode; no matter how far Sarah runs or how well the characters hide themselves, the bad guys show up like five minutes later with absolutely no explanation of how they ended up there. And don’t even get me started on the pencil to the eyeball moment.

Well-meaning bystanders as sacrificial victims. I mentioned above that one of the things I liked about the series was that our heroines tend not to die. Orphan Black gets around this pesky issue and retains its hard edge by pretty much murdering any minor character who decides to help Sarah. This irritates me. I think this is a matter of tone. On one hand, OB is a fun, humorous, somewhat ridiculous thriller, but on the other, it goes for the brutal dystopian view of an Evil Corp run world where bad guys can indiscriminately blow away cops and bartenders with no fear of reprisal. Maybe as writers we can have it both ways, but we have to be much more sparing with our use of senseless violence if we want to keep the viewer/reader who is attracted by a lighter touch.

Overuse of theme music. Helena, the psycho sister, comes with her own sound track. Whenever she’s about to do something wacked, the music becomes what I can only describe as techno noise-to-hack-and slash-to. Perhaps it’s off the Serial Killers’ playlist. As a writer, this would take the form of waaaay overdone foreshadowing. In OB, it actually worked the first few times, but then it became comical. You don’t want to rob your wildly flawed villain/heroine of her impact by making her cartoonish. Again it almost seemed as if the writers weren’t sure if they wanted to be funny or scary.

Cue theme music

Conclusions:

Plot is ultimately character-driven. Anything can happen that’s out of the characters’ control: flood, famine, cloning. How the characters respond is what really matters. You can get away with almost anything if you create characters who are interesting, engaging, and yes, likable. I firmly believe you need at least one character to root for in order to keep the readers interest up past the initial “isn’t this interesting” phase of a book or series.

Allow your characters to Learn From Their Mistakes and to behave differently. While Sarah gets a little bit softer, she keeps doing the same exact dumb things and endangering everyone around her. There are plenty of new dumb mistakes for characters to make, so why keep rehashing the same old ones?

If you’re going to bring in characters simply to give the bad guys someone expendable to kill, do so sparingly. Overuse reduces impact and pisses me off.

If you’re writing a thriller, keep it thrilling. Not a lot of introspection going on in OB, but it works because exciting stuff keeps happening, the characters respond in new and inventive ways (unless they’re Sarah), and there is very little time to worry about all the glaring errors in logic.

Ultimately, I stopped watching. To be honest, it was the abuse of the innocents that finally killed it for me. I’m sure some day I’ll get over it and watch Season 4 and whatever comes next, but for the moment, the errors overwhelmed the genius. Perhaps the main lesson to learn is don’t become so enthralled with your inventiveness that you forget to mind the basics.

Tagged: Characters, fiction, Orphan Black, Plot, writing, Writing Dark Fiction

July 6, 2016

Writing Between the Lines

Photograph by Helgi Halldorsson

Description is boring … or so people say. Few people want to read page after page detailing the intricacies of a landscape or a room, or cataloging the attributes of character, however interesting they may be. But how then do good writers convey their settings and characters so well that we feel as if we were there, or that we knew exactly what a character looks like? It helps to change your perspective on what is really going on.

If you think of description as something that happens only within the lines of your text, and that only that which is included will be experienced by the reader, you are missing the point. The text is only a signpost used to orient the reader’s imagination, and allow it to engage properly. The real magic is happening between the lines. So it helps to think of description not as description, but as evocation. The words are like a spell creating the dream image of a place or a person in the imagination of the reader. Too many words and the dream will collapse, too few, or not the right ones, and the dream will not arise.

So the trick is not to describe a setting or character, but to evoke the setting or character. Just by changing the way you think about this, you will likely discover, all on your own, new effective ways of doing this. With just a short line of dialogue an entire character can be evoked. With a few choice details an entire setting can be evoked. You can’t describe everything, but you can evoke everything if you write not just for what’s in the lines, but what’s between the lines.

Tagged: creativity, fiction, Matthew Lowes, writing

June 29, 2016

How To be a Writer, “Sort of”, by Eric Witchey

Image Source: Alan M. Clark

How To be a Writer, “Sort of”, by Eric Witchey

“Eric is a writer… sort of.”

This is how a friend of mine, a New York Time best-selling author, introduced me to my local bookstore owner during one of her signings last year. No matter that I had been a full-time freelance writer since before she went to high school. No matter that I had known her since before she had sold a single story. No matter that I had been introduced to the bookstore owner at least five times in the past and he didn’t remember my face or name. None of that much bothered me. I’ve experienced that phenomenon over and over in my 26 years of full-time, freelance writing. I don’t look like dollar signs to the local guy, so he forgets me. However, the “sort of” bit from someone I thought was a friend hurt.

It spun me up. It made me stupid for the rest of that evening and part of the next day. It stuck in my heart and head for a long time.

Yesterday, I had lunch with a friend who was once one of my students. I met her while teaching technical writing, WR 227, for the local community college. I thought of that job as community service because I always lost money at it. The treatment of all teachers, and adjuncts in particular, is a topic for another blog. However, the experience was great for me. I met this woman and a number of other inspiring adults putting themselves through college and sharing the classrooms with kids fresh out of high school.

One guy I remember was struggling hard to get a C in my class. Most people who got a C from me didn’t work hard to get it. Most people who got a C (or lower) had to work hard at not getting a B. They drank too much. They played too many video games. They procrastinated themselves into half-assed work. This guy, however, was fighting a stacked deck. His parents had brought him into the US illegally to pick beans and strawberries when he was four. Because of their illegal status, he lived isolated in a non-English speaking community until he was old enough for grade school. He fought prejudice, language barriers, and local cultural politics to get through high school, win his citizenship, and establish a small business. Raising a family of his own, he was also putting himself through college and taking extra classes to improve his English.

Anyway, one day, I asked him, “Why are you going to college?” It was a standard “teacherly” question designed help the student find and focus their motivation for completion of a difficult final paper. I was on teacher autopilot. I expected one of the usual answers, “So I can get a better job,” “so I can go to X four-year school,” “so I can get a promotion at work,” or “so I can ….whatever…” Then, I would so cleverly connect the paper to his stated goal in a way that would, theoretically, allow him to buckle down and work while keeping his eye on the prize. In short, I was a cliché living out a script of clichés.

He was not on autopilot. He said, “Because my boys are 4 and 6. By the time they get to middle school, I want to have a degree.”

Okay, that wasn’t actually a full answer, but it got my attention enough to break my lazy teacher script. I said, “I don’t understand.”

He said, “I want my boys to know that it is normal to go to college, so I have to get a degree.”

Holy shit! I mean, the guy is struggling with English, a business, a family, and to get a C in my class. The cultural deck is stacked against him. His greatest goal in life is to teach his children that college is normal. In his position, he shouldn’t even know he could get a degree. Nobody in his family could even read. The cultural currency of his life should have constrained him to aspiring to be the foreman in a berry field.

My whole frame of reference shifted hard. This guy wasn’t there to get a better job, to make more money, to blah, blah, blah… He was there to establish a new bar of assumption for his family and the generations that followed.

He started in the Mexican highlands near Guatemala. His family didn’t even begin with Spanish. He had to learn that. At four, he traveled on foot to a foreign country to take advantage of an opportunity where, from my perspective, his family was abused, underpaid, and treated like shit. He learned a another language, fought tooth-and-nail to learn in that new language, created a business that generated jobs, married, started raising a family, and deeply and truly understood that what a person accomplishes in life can be influenced by the assumptions that surround them, cultural currency.

For example, if your parents or the people around you went to college, college seems like a thing you can do. If they didn’t, you don’t even think about it.

Back to my lunch friend. She and her family are about to move out of the area, and she wanted to say goodbye. She sat across from me in tears trying to express her gratitude to me for having helped her with letters of recommendation and other encouragements. She had finished her four-year degree and, having graduated at the top of her class, had been accepted with scholarships to a number of Ph.D. programs.

I kept deferring her thanks, reminding her that she did the work, that she got the jobs, that she applied to the schools, and such. I was on cliché teacher auto-pilot again.

Finally, through the tears she was fighting back, she said, “Just acknowledge my thanks.”

Well, shit. I did. I got all teared up. My heart got all hard-beating and warm. Crap.

I won’t go into her background here except to say that every time I think I’m working hard, I think of her to remind myself that my frame of reference needs to be adjusted. When I think of some amazing accomplishment in my life, I think of her and remember that I have a long ways to go before I will come close to true success.

Today, or maybe tomorrow, I have a new collection of short stories coming out. This coming month, that collection and a novel will be coming out in paper. Yeah! Will my local bookstore owner see dollar signs when he looks at me? Probably not. Both books are coming out through a small press. Neither is likely to become part of the pre-order, velocity marketing system that creates the New York Times list.

On the other hand, when I was in high school, one of my guidance counselors thought my eye-hand coordination would make me a good factory worker for the local steel mills. It did for a while. Later, when I was trying to break my drug addiction and get into college, an ivy league school Ph.D. at my ag school told me I had no chance of ever making it into school, and he said I’d die before I was 35.

So it goes.

On the other, other hand, in high school, a couple of my teachers looked at me, squinted a little, and said things like, “The way you look at things can take you out of this town,” and “this poem is really good.” In college, a couple of my professors said things like, “That’s an A, but you can do better.” Thank you Harriet Snyder, Jim Hunter, Barbara Lakin, and on and on and on.

And that brings me full circle to being a writer “sort of.” The woman who said that worked very hard to become the author she is, but she didn’t work sneak into a new country, learn a new language, be the first to graduate high school and put yourself through college while running a business and raising kids hard. She didn’t work surviving drug addict parents, prison, stolen children taken to another country, get them back, put herself through college, create social programs to help women, get a full scholarship to a Ph.D. program hard. She began with a loving family, middle-class education assumed, supporting love, and fulfill your dreams baseline. And, yes, she worked her ass off.

Of course, she worked hard. Of course, she overcame many obstacles. She accomplished many wonderful things, and I love her books.

That’s not the point. The point of this little essay is cultural currency. We know what we know. We don’t know what we don’t know.

When I was in that Middle America steel mill town, I didn’t know different universities had different reputations. I couldn’t even ask questions about that because I didn’t know I didn’t know.

I did know that if I worked hard I could go to college. My mother and father both did. My older brother did.

I didn’t know that I suffered from a birth defect that stunted my production of certain neurotransmitters that would eventually turn me into an addict and that kept me from ever working in the way that would let me actually go to college.

Nobody could know that back then. It wasn’t a known thing.

Now, I know it.

I know it because I learned it as part of breaking my drug habit. I know because I learned it as a result of reaching, searching, and trying to understand why the world looked the way it did to me and made no sense to others when I tried to describe it. I learned it from seeking help, getting tested, getting diagnosed, and working with a number of gifted doctors and therapists. I even learned to compensate and overcome. Lots of people do.

Now, looking back, seeing what I once thought of as pettiness and self-importance of so many people I have met over the years, I realize that all of us are limited by cultural currency, by what our world showed to us, surrounded us with, taught us was good, right, wrong, possible, and impossible.

Sustained presence of the New York Times best seller list is pretty much considered the epitome of success by many writers I know. It is one hell of an accomplishment. I’d love to do it. However, it is really only a moment, a symbol that represents a journey in life. It does not demonstrate how long the journey has been or the how far the distance between the understanding a person begins with and the complexity of the problems they must solve to move forward. It is only a badge, and it is a good badge.

Success, however, is not a badge. Success is standing in a dark room surrounded by nothing useful and deciding that something better must exist beyond what can be known. Success is the creation of a set of assumptions for a generation not yet formed and who will never know what you went through in order to create those assumptions. Success is the distance between what you could not know and what you learned. Success is neither a dollar nor a badge. It is the ability to know that what you have done was impossible for you and to have still done it.

I celebrate the success of my NYT best-selling friend. I don’t know what was and was not possible for her. Only she knows that.

I celebrate my own successes. Looking back over the road of my life, I do know what was and was not possible for me. I am inspired by the success of my tearful, grateful student-friend. Terrified, she has lived in the darkness and constantly sought to move beyond it, motivated only by her faith that more existed and that if she reached she might grasp it for herself and for her children. I am inspired by the man who began in the forest in an illiterate family who spoke neither Spanish nor English and who worked to create a new understanding of what is possible for his children.

We can all be petty. I know many writers, and we writers abuse the hell out of ourselves, and quite often we casually judge others for what they have done or what they have not done.

Writers have all read at least one book and thought, “Well, that sucks. My work is better than that. Who’d he sleep with to make his book famous?”

Writers have all justified their unfulfilled hopes with statements like, “My last three well-respected agents turned out to be liars and thieves. She was just lucky. Her first asshole agent got her a three book deal.” or “That guy campaigned to win his award. He’ll never know if the story was really any good or not.”

Writers convince themselves of their own superiority with thoughts like, “I wish she’d stop coming to our critique group. She’s flooding the group with stories, and she makes the same mistakes over and over.” or, “If he worked harder, he might be as good as me.”

Writers are people. Most people engage in this kind of personally limited judgment of others. Even the people who are reading this right now and thinking, “I don’t do that,” or, “So-and-so does that all the time,” do it.

All of these casual judgements are a demonstration of cultural currency limiting us. None of them are demonstrations of sneaking into the country, learning a new language, creating a new frame of reference for a new generation success.

Only reaching out from the darkness with faith and fear creates that kind of success. Only creating the next story, a story that lets the people who are reaching in the darkness believe that they will grasp something wonderful creates that kind of success. Only gratitude, love, and respect can create that kind of success.

The badge would be nice. It’s pretty. I want a badge like that. The recognition of my author friend for my journey would be nice. To some people, my accomplishments are many and amazing. To others, like the bookstore owner, they are small and not worthy of a handshake.

To me, they are my life.

Today, I cannot know what I do not know. I can, however, reach outward from my darkness and take action. I can learn. I can meet people where they are and listen. Sometimes, I can teach. Most of all, I can remember that no matter who I meet, no matter where I meet them, the fact that they are with me in that moment means that we are sharing success within the knowing we have inside the lives we are living. When I introduce them, no matter what badges I might wear or want, I hope I can demonstrate my respect for them and what they have survived and accomplished. When I look at myself in the mirror, I hope I can demonstrate my respect for myself and what I have survived and accomplished.

Today, I am a writer, sort of. I wrote this.

To reach out from our darkness is to succeed.

-End-

June 23, 2016

Tools of the Trade

By Cheryl Owen-Wilson

I think we can all agree—writing is a most solitary art form. While I can paint with a room full of other painters exchanging ideas and telling stories, when I write I require either complete silence or music of my own choosing. There is no one sitting behind me handing me ideas as my fingers fly over the keyboard or whispering suggested words when I am stuck in the middle of a too often used, tired cliché’. Close your eyes and visualize your picture of a writer. I’m certain they are sitting in seclusion, even in a noise filled coffee shop, brow furrowed, possibly staring at a blank white screen/page or hopefully they are frantically writing before the words disappear “poof” from their brain’s frontal lobe.

So given the seclusion of writing, I was quite taken aback when attending a recent event in which the speaker, an author, eschewed the benefits of “Writing Critique Groups”. Said author went around the table of attendees and asked. “Who belongs or has belonged to a writing critique group?

Of the roughly sixteen people in attendance I quickly ascertained most were new to the writing community. Three of us said we benefited from our writing groups, one said they did not, and the remainder had, as I mentioned, no experience. The author then proceeded to give a lengthy dissertation as to why she did not think writing groups were beneficial—her two main complaints were—too much socializing and not feeling her writing benefited from any critique another writer could offer. She also placed writing conferences in the same bucket—adding cost to her other arguments listed above. I sat stunned for the remainder of her presentation.

When I left the building my mind would not stop rebuking me for not speaking up on the benefits I personally have received from my 20 plus years in and out of writing groups. I kept envisioning those new writers in attendance who might—given the speaker’s vehement aversion—never know the many benefits I and many published authors I know, have obtained over the years.

Without writing groups and conferences I would not have the readily available support of a wide community of writers, not to mention the value of life-long friendships. If you are at the beginning of your writing life, I feel these are valuable tools that will save you many hours of trial and error. With the way the industry is evolving I feel it’s more important than ever to have a strong, core network, and that can start at conferences or within writing groups. Following is a very brief synopsis of how my writing groups have benefited my continuing evolution as a writer, and artist:

Cheryl’s Writing Groups

The first 8 years—“Wild Women’s Writing Group”—We were four very green individuals who have remained friends to this day. Both fortunately and unfortunately we fell into the biggest pitfall—as mentioned by the guest author above—we became more of a social group. However, two of us have continued writing. One of the four was only eighteen when she started, and may not have the 10+ books she has published today if not for this first writing group.

The next 12 years—“The Inklings”—While there have been months where this group did not exist it always rekindled and began again. Different individuals have populated it, but two of us have remained through it all. I can now count myself a published short story author, published illustrator and creator of a book cover. None of which would have happened without this current writing group. I can’t speak for them individually, but I can say they are each published as well. One member in this current group, began a career in a new genre due to the success another member was having in the genre.

I can also say, at this very busy stage of my life—family, day job, artist—without a writing group to hold me accountable to put words on a page I might not achieve even the small—by comparison to the others in our group—word count I do manage to turn in at each meeting. After each meeting—critiques in hand—I feel I’m one step closer to completing a short story—one step closer to finishing a novel—one page closer to having a larger audience read my stories.

Long ago I was given a very simple outline on how to begin a writing critique group. Here is how it has evolved over the years:

Meet the same time, same day of the week—weekly, bi-weekly, monthly—whatever works best for the group.

Keep the group number to 4-6 attendees.

Set a maximum word count based on the size of the group, and how long you wish the meeting to last.

The meetings are no host meetings. You are there to critique not to socialize—as I mentioned this is the biggest pitfall to a successful group.

Each member is to submit via email, what they wish to have critiqued by a specified date prior to the meeting.

Come to the meeting with printed copies you have already read, and which you have written your critiques upon.

At the meeting your submission will be read by another attendee—this is fabulous not only for individuals who have a hard time reading their writing in public—but there is great benefit in hearing your writing in a voice other than your own.

The person who reads will critique the piece first. You will then go around the room and each give additional commentary. If necessary have a timer for each critique. Please remember to comment on what you like as well.

The author is then given each copy—with the name of the person, who gave the critique, in the event they need further clarification—to take home so they can begin the fun of editing of their story or not. Remember your writing group is for your benefit.

It’s as simple as that. You say you’re not ready to have anyone critique your work? That’s fine too. But I personally think you’ll be missing out on what might be a lifeline to sanity. There really are other people out there who have voices in their heads wanting to live on the written page. Now, you can still go back to writing in solitude and seclusion and ignore everything I’ve just said, but I felt it important to say it.

Before you go, please give me your positive or negative experiences/thoughts regarding writing critique groups.

June 15, 2016

The Space Between

By Cynthia Ray

I’ve been exploring the space between things over the last few months, in my life and in my art. It all began with Viktor Frankl. In Mans Search for Meaning, he says, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

What he said about the space between stimulus and response fascinated me, because our words and actions seem so automatic, I couldn’t imagine having that much self control, so I spent time observing, trying to find that space. After a while, I was able to slow down enough to feel the space between, but not enough to change or stop my response. I kept at it, and eventually, after much practice, I was able to slow down even further, and could remain poised there, between the catalyst and my reaction, long enough to choose a new and different response than I had automatically followed in the past. It’s an exhilarating and powerful tool, but like anything, requires practice.

What he said about the space between stimulus and response fascinated me, because our words and actions seem so automatic, I couldn’t imagine having that much self control, so I spent time observing, trying to find that space. After a while, I was able to slow down enough to feel the space between, but not enough to change or stop my response. I kept at it, and eventually, after much practice, I was able to slow down even further, and could remain poised there, between the catalyst and my reaction, long enough to choose a new and different response than I had automatically followed in the past. It’s an exhilarating and powerful tool, but like anything, requires practice.

But the space between things is much more than the space between stimulus and response. All of art is about the space between. Where things are placed, how far they are from each other in relationship to each other in a painting is more than just perspective. It is balance between what is and what is not. Music is the space between notes. If that is true, then writing is the space between the words.

The Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading by Paul Saenger talks about how the spaces between the words were consciously created to move us from oral to a written tradition. We take all of that for granted now, but it was not always so.

He says, “Over the course of the nine centuries following Rome’s fall, the task of separating the words in continuous written text, which for half a millennium had been a function of the individual reader’s mind and voice, became instead a labor of professional readers and scribes. The separation of words (and thus silent reading) originated in manuscripts copied by Irish scribes in the seventh and eighth centuries but spread to the European continent only in the late tenth century.” This resulted in the spread of reading and education among the common people, not just the elite.

Not only does the space between words give order to the story, and make it possible to find the story in the words, but those spaces also carry deep meaning and impact. What is happening in dialogue? What is not said? Sometimes what is not said is far more powerful than what is said and carries a message that can break us apart. Its not the words that are said, but the ones that are not. Sometimes the best dialogue is not dialogue.

I started watching what my characters were doing in the space between their actions, in the space between their dialogue, in the space between the catalyst and their response. It is a wonderful place to explore interaction, feeling and nuances. Looking at what is not, rather than what is, or at what is between what is and what is not.

If we slow down and take the time to pay attention to that which is hidden right in front of us, we can find those vast in-between spaces in ourselves and the universe we live in to inform our relationships, our lives and our art.

In the space between

the in breath

and the out breath

lie all the worlds

In the place

between heartbeats

all the worlds

tumble to silence

between one thought

and the next

stillness extends out into the universe

C. Ray

Tagged: Characters, creative process, creativity, fiction, Psychology, writing

Shared ShadowSpinners Blog

- Eric Witchey's profile

- 51 followers