Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 595

September 14, 2015

The World Is Changing Faster Than You Think

Japan’s population may be shrinking, but the Land of the Rising Sun has no intention of letting its economy shrink as well. Bloomberg has a deep dive into how Japan’s powerhouse robotics industry is keeping its economy afloat in the face of challenging demographic changes:

The rise of the machines in the workplace has U.S. and European experts predicting massive unemployment and tumbling wages.

Not in Japan, where robots are welcomed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government as an elegant way to handle the country’s aging populace, shrinking workforce and public aversion to immigration.Japan is already a robotics powerhouse. Abe wants more and has called for a “robotics revolution.” His government launched a five-year push to deepen the use of intelligent machines in manufacturing, supply chains, construction and health care, while expanding the robotics markets from 660 billion yen ($5.5 billion) to 2.4 trillion yen by 2020.

Japan’s surplus of capital and technological know-how combined with its aging population and hostility to mass immigration makes it well-situated to become a robot superpower. If a job can be automated—from health care to table service in restaurants—the Japanese will figure out how to do it.

This is going to have a big global impact. It’s expensive to develop new kinds of robots for new and more complex tasks. In countries where labor is relatively cheap, it wouldn’t make sense to invest millions of dollars in machines that can replace a lot of low-skilled workers. But it makes lots of sense in Japan, with its shrinking population and tightening labor market. Once the initial investments have been made and the technology exists, the marginal cost of each robot will fall dramatically. This means that the it will be economical to use the robots even in places where labor is significantly cheaper.There’s a second dimension to the implications of Japan’s robot revolution: Many people have assumed that because certain countries (think: Germany and Japan) face aging and shrinking populations, their growth will slow and their influence will wane. At least in Japan’s case, they could be in for a surprise. After all, given the trends in global demographics, Japan may just be getting to the next stage of history a little faster than the rest of us. That means that what Japan needs today, the rest of the world will need tomorrow. Investing in robot technology can put Japanese companies back where they were in the glory days of the 1980s, when cutting-edge Japanese goods were in high-demand around the globe. Becoming the Silicon Valley of the robot revolution is a good business plan for Japan, Inc.Finally, the military implications are also significant. A country that leads the world in robots, automation and technology is going to be a significant military power even if it doesn’t have a lot of 18 year-olds in its infantry. By extending its already significant technological edge over China, Japan can compete much more effectively against its giant neighbor in regional power politics than conventional opinion currently allows.Japan has problems—a huge debt load, the cost (even with robots) of caring for an aging population, hostility from China, poor relations with South Korea, a corporate and bureaucratic establishment that resists innovation, deep pocketed special interests that have bought and paid for legislative allies—but it has assets too. In the 1980s and 1990s the chattering classes ignored Japan’s problems and focused on its assets; since then they have done the opposite.Don’t write it off the Land of the Rising Sun. If the robot revolution takes hold, a big chunk of the 21st century will be made in Japan.Iran Announces “Unexpectedly” High New Uranium Deposits

Iran’s leaders must be shocked—shocked!—to have discovered, just months after signing a nuclear deal with the U.S. and days after it became clear that Congress would not be able to overturn it, that it had much more uranium than previously thought. Reuters reports:

Iran has discovered an unexpectedly high reserve of uranium and will soon begin extracting the radioactive element at a new mine, the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization said on Saturday.

The comments cast doubt on previous assessments from some Western analysts who said the country had a low supply and sooner or later would need to import uranium, the raw material needed for its nuclear program.[..]“I cannot announce (the level of) Iran’s uranium mine reserves. The important thing is that before aerial prospecting for uranium ores we were not too optimistic, but the new discoveries have made us confident about our reserves,” Iranian nuclear chief Ali Akbar Salehi was quoted as saying by state news agency IRNA.Salehi said uranium exploration had covered almost two-thirds of Iran and would be complete in the next four years.

The U.S. State Department told Reuters through a spokesman that new discoveries would also be subject to the agreement, and monitored. However, this announcement will likely remind critics of the debate over Iran’s disclosure of PMD (potential military dimensions)—the account of its previous activities that would serve to benchmark inspections going forward. Skeptics pointed out that if we did not have a sense of where Iran had been, it would be harder to judge cheating going forward.

Likewise, the new “discoveries”—even Reuters put the word in quotes in one story—of undisclosed amounts of uranium will likely make monitoring the deal more difficult. And more such news may be to come—the Iranian government claims to have only surveyed 63% of the country for uranium so far, but promises to finish soon.One wonders how many more times the Iranians will discover—unexpectedly!—good news as the deal moves forward.Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

There are few miseries more widely felt than the pains of sitting in traffic. Daily, millions of commuters take to overused, often poorly maintained roads and head towards their many destinations. While congested roads may seem like an unavoidable constant of life—and to some extent they are—a new study from the nonpartisan think tank Common Good suggests that a considerable amount of this inefficiency is the result of an over-complicated process for the approval of new projects. From the WSJ:

In 2009 the Obama Administration air-dropped $800 billion of taxpayer cash known as the stimulus package, but as of last year a piddling $30 billion had been spent on transportation infrastructure. One reason the projects proved not as “shovel ready” as promised is that proposals must undergo extensive environmental and permitting reviews, which leave no tedium behind in part to avoid litigation. […]

One irony is that delays mean more carbon energy use. Roughly 6% of energy pumped out for public consumption is wasted thanks to America’s superannuated electricity grid. That works out to about 200 coal-burning power plants, the study notes. The same is true for congested roads, on which motorists guzzle gas in traffic while they wait the average six years for a major highway project to be approved.The expense adds up: A six-year delay on public projects costs more than $3.7 trillion, the report found. By the way, the amount needed to update dilapidated bridges, water pipes and so on over the next decade is half that, at $1.7 trillion.

Reform of the licensing process for infrastructure projects is a vital part of the restructuring government needs. Layers of conflicting mandates, bureaucracies with overlapping responsibilities, and legal and regulatory processes that are sluggish and out of date make necessary projects and repairs slower and much more expensive than they need to be.

But this is just one window into the many ways that our government processes and bureaucratic institutions are too slow—and how this inefficiency imposes huge costs. Private business faces the same kinds of delays and obstruction when it comes to permits and clearances.The gap between the performance we need and the performance we have is particularly frustrating because if there is one thing the information revolution ought to be able to accomplish, it is the acceleration of government decision and permit processes. Bureaucracy is best understood as an early and primitive form of computational system, using the equivalent of algorithms to analyze particular requests and actions. Law courts work much the same way.What we call the ‘rule of law’ is the rigorous application of legal and regulatory norms to particular cases: much (though never all) of this can be done in the 21st century more effectively (faster, cheaper, fairer) by processes that take advantage of the enormous ability of information technology to accelerate the processes of analysis that bureaucracies grind through so slowly and painfully—and with so many places where bribes and political cronyism can be brought to bear.Our society is inevitably getting more complicated: the population is growing and the complexity of modern life create denser and denser networks of overlapping interests and concerns that require ever more complex legal and regulatory systems to adjudicate and manage. That is all the more reason why we have to take up the task of upgrading the way our legal and regulatory systems work. Otherwise, American society will strangle in red tape.Kurds Mourn Dead—and Their Hopes for a Better Turkey

One hundred thousand Kurds gathered in the city of Cizre yesterday to mourn their compatriots killed during a recent Turkish army crackdown. The Daily Hurriyet reports:

The mourners carried the coffins of 16 people to a funeral ceremony before their burial.

The Turkish government said up to 32 outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants were killed during the curfew imposed in Cizre in an “anti-terror” operation.But the Kurdish-problem-focused Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) said 21 civilians were killed during the operation, which deprived residents of access to essential amenities and triggered food shortages.

Erdogan’s strategy seems to be clear. For a critical slice of the electorate, a traditionally Kurdish party became a rally point for opponents of Erdogan’s plan to amend the constitution and gift himself with powers to match his new palace. The success of this party deprived the AKP of its hoped-for majority. Rather than abandoning his grandiose ambitions, Erdogan has embarked on a strategy of polarizing Turks on the Kurdish question, ratcheting up tensions in Kurdish areas, and exacerbating Turkish-Kurdish relations. This is especially sad because in the past one of Erdogan’s genuine accomplishments was to move toward a more open and reasonable Kurdish policy that might have helped overcome years of suspicion and violence.

What Erdogan appears to want now is a synthesis of the worst of Kemalism (intolerant authoritarianism and rigid nationalism) with Islamism. By playing the Kurdish card, he now hopes to attract support from hardline nationalists and continue to rebuild links with the military. There are few sadder spectacles in world politics today than the ruin of the hopes Erdogan once raised for a brighter, more democratic future for the Turkish people.Tory Coup in Australia

An internal challenge from the centrist wing of his own party has overthrown the Prime Minister of Australia. The Wall Street Journal reports:

Malcolm Turnbull will succeed Tony Abbott as Australia’s prime minister after a party rebellion that may moderate the country’s stance on issues ranging from same-sex marriage to climate change and economic policy.

Mr. Turnbull called for a leadership ballot earlier Monday as voter surveys pointed to defeat for the ruling Liberal-National conservative coalition at federal elections due next year. The 60-year-old former investment banker defeated Mr. Abbott by 54 votes to 44.

Australia can’t be a banana republic, because its voters have never agreed to replace Queen Elizabeth with an elected President. But otherwise, after generations of a fairly stable political environment, it seems to be moving to a much more volatile system.

The last Labour government had as much plot as Macbeth, with backstabbings, palace coups, and intrigues galore. Prime Ministers came and went until the voters swept out the whole pack—despite a solid economy.Now the Coalition, a center right group, is going through the same kind of tumult. Abbot became leader of the Tories by staging his own intra-party coup against Turnbull while both were in the Opposition; he was then elected Prime Minister in 2010. Abbott has had a turbulent run in office (not helped by China’s economic troubles, and the fact that Australia may be facing its first recession in 24 years), and he already survived one formal challenge to his leadership in February. Now, Abbott is back out of office and Turnbull in—but today’s events hardly seem a recipe for long-term stability in the ruling party.What happens to Australia matters more to the world than it used to. Like Canada, it is a rising power. It has a sophisticated economy, strong educational system, growing population, good record with assimilating immigrants, and an extraordinary resource base. Both Australia and Canada seem to be encountering some political turbulence as they rise; that’s not unusual. In rising powers with rapidly developing economies and evolving societies, political institutions and parties have a hard time keeping up with the changes in the wider society. And as countries become stronger economically and more important politically, their global interests become more complicated, and domestic struggles over foreign policy can become harder to resolve.One of those struggles will likely affect Australia’s relations with the United States. Turnbull is a member of the Australian school that believes the country needs to balance more effectively between the U.S.—Australia’s main security partner—and China, its main economic partner.Australians who take this view are liable to misunderstand the nature of China’s rise, and to underestimate the importance (economically as well as strategically) of the network of powers from Japan and Korea to India that are creating a new Asian alignment. As a result, the China School could end up weakening Australian ties with the U.S. and other important states in Asia without gaining anything from China.Australian foreign policy shouldn’t consist simply of saying “Yes, sir!” and saluting every time Washington makes a proposal. There are ways that Australia’s location and interests give it important insights into common problems, and if Washington is smart it will listen closely to what Canberra has to say. But the China School seems to misunderstand the nature of the impact of the rise of China on regional politics, overestimating what China is capable of doing and underestimating the determination and capability of states like India, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan to balance China’s rise. A rising China makes alliance politics more complicated and more important for Australia as well as for other countries in the Pacific—that much the China school gets right. But the answer isn’t to distance oneself from allies and partners; it’s to engage more deeply and thoughtfully in order to develop effective ways to promote peaceful Asian integration.At the end of the day, though, these domestic struggles and foreign quibbles are mostly the growing pains that come from Australia’s increasingly important role on the global scene. In the 19th century, the UK dominated the Anglosphere. In the 20th century, it was the U.S., with Britain reduced to second fiddle. The U.S. won’t be fading away in the 21st century, but the Anglosphere may start looking like a string quartet, in which four distinct but connected fiddles make music that intrigues (and sometimes infuriates) the whole world.Europe’s Failing Dream

“We are not forming coalitions of states, we are uniting men.”

—Jean Monnet, founding father of the European Union, 1952

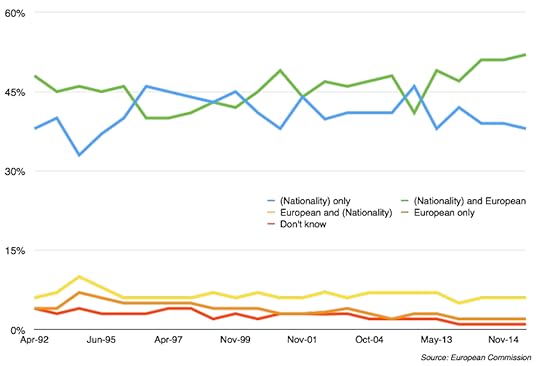

—Marine Le Pen, leader of France’s National Front, 2014If French presidential elections were held today, Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Front, could come out on top in the first round. Ms. Le Pen would easily beat the current president, François Hollande, and might even edge out the center-right’s most likely candidate, former President Nicolas Sarkozy, according to recent polls. Voters hostile to the National Front would still band together to hand Marine a defeat in the second round if elections were held today, the same polls show. She would, however, end up carrying between 41 and 45 percent of the vote.And that poll was held before the migrant crisis convulsed Europe.The National Front, the party founded by Ms. Le Pen’s father Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972, has never been as popular as it is today. At the height of his own popularity, Mr. Le Pen won 16.9 percent of the vote in the first round of the 2002 presidential elections, but was soundly defeated in the second round. His daughter, who took over the party leadership in 2011, beat her father’s best showing on her first try, coming in with 17.9 percent of the vote in the 2012 elections. With the atmosphere in France increasingly uncertain, she may well have the shot in 2017 that her father never did.And the National Front is not the only far-right party on the popularity upswing. All across Europe, far-right parties are making big strides. In Hungary, the ultranationalist Jobbik party, whose members have been accused of holding rabidly anti-Semitic views, is riding high in the polls and is now the second strongest party in Hungary. In April of this year, Jobbik’s Lajos Rig defeated the favored candidate from the ruling center-right Fidesz in a by-election that the party’s gloating leader, Gabor Vona, described as “historic.” Similar successes are on display in Austria, where the Austrian Freedom Party had one of its best performances in 2013 when it captured 20.5 percent of the vote in parliamentary elections; in Denmark, where the Danish People’s Party is the second largest party in parliament as of the 2015 elections; in the Netherlands, where the anti-immigrant PVV is currently pulling ahead of the mainstream VVD in aggregate polls; and in Finland, where the euroskeptic True Finns have joined the government after getting 13 percent in the latest elections. Even in traditionally left-leaning Sweden, the anti-immigrant Sweden Democrats are the number one force in the country. With far-right parties becoming a rule rather than the exception in mainstream politics, the political landscape in Europe has been transformed.The appeal of far-right parties seems to have caught European centrists by surprise. But it shouldn’t have. For decades, mainstream parties turned a blind eye to the “crazies” on the right. United behind the European project, center-left and center-right parties forged ahead towards a bright European future. They missed—or more likely simply chose to ignore—the simmering anti-immigrant and euroskeptic sentiment in their constituencies. The financial crisis of 2008 has acted like a force multiplier for these feelings: by showcasing the ineptitude of the ruling elites in addressing the serious challenges facing voters, many people only tentatively identifying as Europeans found they have a real appetite for the resolute certainties offered by strong nationalist programs. And a more mature far-right, groomed by years of failed attempts at power and steeped in a newfound pragmatism, was ready to pounce.The Weak Roots of Monnet’s Dream Jean Monnet, the founding father of the European Union, had grand ambitions for the European coal and steel partnership that was established in 1951. Monnet foresaw a Europe united not only by markets and political institutions, but by a common sense of cultural belonging: a unique European identity would supersede the nationalist impulses that had left Europe ravaged by two world wars. The new Europe was to be a beacon of democracy and tolerance, a social union of European citizens grounded in shared Enlightenment ideals. A common currency would be more than a medium of exchange: it was to bring this uniquely European identity into being.For the next fifty years, Monnet’s grand vision appeared to be on its way to being fully realized. The Treaty of Rome established the common market; six member states became twenty-eight; border guards gradually began leaving their posts, ten years after the signature of the Schengen Agreement; EU passports were printed; plans for a common currency were drafted; a state-like bureaucracy emerged, equipped with a parliament, an executive branch and judiciary. By the turn of the millennium, with the euro being introduced, a European United States seemed tantalizingly within reach. France’s Finance Minister Laurent Fabius confidently predicted that “thanks to the euro, our pockets will soon hold solid evidence of a European identity.”That dream of a shared European identity, however, never gained the kind of purchase its most fervent supporters hoped for. A decade and a half after the introduction of the euro, Eurobarometer polls show that a full 90 percent of Europeans see themselves first and foremost in either solely national terms—as German, French, Italian, etc.—or as an admixture of national first and European second, whereas only two percent see themselves as solely Europeans. Research I conducted with Neil Fligstein and Wayne Sandholtz shows that the two percent of self-described “full” Europeans tend to be an elite group: wealthy, well-educated, white-collar workers who speak multiple languages and travel often. This group of transnational elites, perhaps not surprisingly, has also been the primary beneficiary of the European economic project. While the highly skilled have been able to take advantage of the common European labor market, the majority of their compatriots have had a very different experience. Particularly since the financial crisis of 2008, the “have-nots” of Europe have seen their economic prospects wither.

To further understand how economic decline affects individuals’ sense of belonging, Neil Fligstein and I analyzed Eurobarometer surveys before and after the financial crisis, in 2005 and 2010. In a forthcoming paper in the Journal of European Public Policy, we find that citizens of countries worst hit by the economic crisis—most notably in Greece, Spain, Italy, and Ireland—became more nationalist. Specifically, in countries where GDP fell and debt increased by the largest margins, individuals became more likely to define themselves in national terms, looking to their national governments for protection from worsening economic conditions. This tendency appears to hold across demographic characteristics, political views, or educational backgrounds.But the Eurobarometer data goes only so far. It suggests that the early theories of visionaries like Monnet and of political scientists like Ernst Haas—that economic integration would beget political cooperation, which would in time birth a new ‘European nationalism’—have not panned out. It tells us that the impressively broad and robust-seeming bureaucratic and economic edifice that has been built on the European continent since World War II has yet to put down deep roots in Europeans’ cultural consciousness. It suggests that the European dream is in trouble, especially in today’s febrile political climate, given the strong relationship between economic hardship and a decline in support for European identity.It does not, however, explain how the dream is failing and what its vulnerabilities are. My own research, detailed in a recently published book, has found that economic distress alone has historically not been enough of a motivator for Europe’s voters to wholly embrace an anti-European nationalist politics. However, when economic worries are coupled with concerns about immigration in a broader climate of declining societal trust, people start to look to the political extremes. Other research has shown that generalized hostility towards the EU explains far-right voting over and beyond all other socio-political attitudes, including feelings of ethnic threat from minorities and general xenophobic attitudes.Put those two insights together and you begin to see the broad potential appeal, and staying power, of the new far-right in Europe. Monnet’s dream, for all its grandiloquent promise, has stalled at the economic level. Its successes there are real enough, of course. People understand and appreciate the benefits that a common market and common currency has brought them—51 percent identified the free movement of people, goods and services, and 25 percent identified the euro as among the most positive achievements of the EU in the 2014 Eurobarometer—and this appreciation probably goes part of the way to explaining the attitudes of people who self-identify as national first and European second. Looking across time, the number of these “European second” people has been growing at roughly the same rate as the number of people identifying solely in national terms has been declining. Yet as we shall see, this secondary Europeanness is a weak glue that is relatively easy to pry apart.Greeks Bearing Debts: Euroskepticism In Name OnlyThe Greek financial crisis, which has dominated European news coverage for the better part of the year, was the first high-profile case of where a radical (so-called) euroskeptic party, the left-wing Syriza, came to power and challenged Brussels. United under the anti-EU banner, some far-right parties elsewhere on the continent cheered Syriza’s rise. But assuming that this alliance of opposites means that functional differences between the far-right and far-left in Europe have disappeared would be too much of a simplification. Syriza, for example, is ideologically not opposed to immigration, while the National Front has campaigned on an anti-immigration platform for decades. And as the Greek crisis shows, this missing ingredient makes a big difference.As the financial crisis began to rattle the eurozone in 2008, investors started examining some of the riskier bets they had made in fat times. The Greek government’s outstanding debt in particular started to look unsustainable. Revelations that the Greeks had systematically cooked their books in the past heightened worries. By April 2010, when credit agencies had downgraded Greek debt to junk status, a consensus had emerged: Greece was on its way to defaulting. By May of the same year, the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the IMF—the so-called “Troika”—was offering to step in with what was to be the first of several bailouts, coming in at €110 billion.Greeks, over 90% of whom self-identified either solely as Greek nationals or as Greek nationals first and Europeans second in 2010 according to Eurobarometer, looked to their own government for leadership and protection amid all the turmoil. What they saw instead was their Prime Minister, George Papandreou of the socialist PASOK, getting ready to agree to a draconian set of austerity conditions attached to the bailout money: demands for deep cuts to social programs, including pensions, healthcare, and government salaries, and an increase in taxes.In Papandreou’s defense, he realized early that his room for maneuver was limited. Having adopted the euro, Greece could not devalue its way out of its debt pile as many southern European countries were all too fond of doing in the past. He knew he would have to submit to whatever demands were made of him, or preside over an unprecedented default by his country.But Greece’s voters were having none of it. Protests demanding Papandreou drive a harder bargain began to multiply. The protesters’ logic was not hard to grasp: in the spring of 2010, the rest of Europe was petrified of the knock-on effects that a Greek default would have on the much larger but similarly troubled economies of Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Italy (the rest of the countries that made up the malevolently-invented acronym PIIGS). Greece actually has a few aces up its sleeve, the reasoning went: Papandreou could get a better deal if only he pushed back harder. A massive strike on May 5, 2010 shut down the country and brought hundreds of thousands to the streets of Athens alone. Protests rumbled on for the next two years, as reforms stalled in parliament and the first bailout was supplemented by a second (bringing the total pledged by the troika to €240 billion).Finally, after Papandreou stepped down in late 2011 after nearly losing a vote of confidence, the twin elections of the summer of 2012 (the May ballot failed to produce a government, so a re-vote was scheduled for June) allowed voters to fully express their frustrations with what they saw as a feckless national elite that had failed to protect their interests. The conservative New Democracy took over the top spot in Parliament, but Papandreou’s PASOK didn’t come in second. Instead, voters began rewarding Alexis Tsipras and his Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza), who captured almost 17 percent of the vote in May, and nearly 27 percent of the vote in June. By January of 2015, Tsipras had a mandate to form a coalition government with 36.3 percent support.But Tsipras’ seven-month tenure—he resigned last month after desertions from Syriza followed his caving to the Troika’s austerity demands—was a study in contradictions. In negotiations with the Troika, he insisted on debt forgiveness and was an uncompromising rejectionist of austerity. Yet throughout the drawn-out process, he would periodically insist that he would not allow Greece to default out of the eurozone. A few short weeks after he got a resounding “no” from voters in a referendum on the terms of the bailout deal, Tsipras turned around and agreed to most of the Troika’s terms when the last of Greece’s liquidity began to dry up in June. Although it later emerged that his Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis had set up a contingency plan that would allow the government to issue payments to all taxpayers in what would amount to being a proxy electronic currency, the Greek government chose not to go down the path of Grexit.His newest rival for the leadership of the radical left, Panagiotis Lafazanis, who spun off frustrated Syriza deserters into a new party, is trying to present a stark contrast, vowing to “smash the eurozone dictatorship” and calling for a return to the drachma. But after Tsirpas’s promise and subsequent failure to secure a better deal with the EU, Lafazanis appears to be equally distrusted. At time of writing, his party, Popular Unity, is hovering around the 3 percent threshold for entering parliament.These seeming contradictions, however, ought not puzzle us too much. The Greek crisis was predominantly economically fueled, and the solutions Syriza was proposing were likewise limited to that domain. Though Syriza’s leaders at times stoked nationalist impulses, particularly in vilifying the Germans as latter-day Nazis, they were careful to insist that their beef was with the unreasonableness of European demands, not with the idea of the EU itself.Looking back, it appears as if Tsipras judged that voters wanted to remain in the EU, and were mainly demanding a better deal from Brussels. And it looks like he was right. Though Greece’s voters emphatically rejected the bailout’s terms in what was arguably a rushed and confusingly politicized referendum in early July, public opinion nevertheless continued to back Tsipras even as he concluded his negotiations and accepted the draconian terms of the latest bailout. Though Tsipras’ popularity has taken some hits since the bailout passed parliament, his Syriza coalition, shorn of its most radical left elements, is still running neck-and-neck with New Democracy for the top spot in the upcoming snap elections. It turns out, there was never much evidence that Greek voters had an appetite for the outright rejectionism that many outside observers feared Tsipras would resort to—or that is now on offer by Lafazanis.The Far Right: All Grown UpIt is important to remember, however, that a certain number of Greeks did turn to the extreme right in the 2012 elections: for the first time in Greece’s post-war history, Golden Dawn, a far-right ultranationalist party with a paramilitary bent, entered parliament with 7 percent of the vote. By the January 2015 election, Golden Dawn was the third largest party in the country, albeit with a slightly diminished 6.3 percent support. And there they’ve stubbornly stayed: show Golden Dawn capturing around 6 percent of the vote in the upcoming snap elections set for late September. Golden Dawn’s venomous racist platform, openly fascist ideology, and willingness to use street violence, all appear to create a hard upper-limit for their popularity. Indeed, some studies have convincingly argued that the most successful radical right parties are those that frame their nationalism against the external threat of the EU: far-right parties that hold on to the old openly racist, blood-and-soil rhetoric tend to fail at the polls. It’s a lesson that Europe’s slicker, more modern far-right parties—the likes of which just don’t exist in Greece—have properly internalized.The most successful European far right parties have pitched themselves to voters as protectors of a civic liberal tradition, which they have nevertheless successfully reframed along national lines. In these party narratives, the EU has become a threat to national sovereignty, and non-European Muslim immigrants have become scapegoats for the loss of national values and the threat to liberal democratic ideals. Far right parties have paradoxically become defenders of European values against the encroachment of both non-European foreigners, as well against an effete elite in Brussels that is seen to be undermining European civilization by its commitment to pluralism at all costs. Cultural issues, rather than purely economic ones, have become the key to catapulting the far right into the political limelight.France’s National Front is a case in point. The battle between Marine Le Pen and her father over the control of the party he founded precisely tracks how the far right has retooled itself all across Europe. In April 2015, Ms. Le Pen publicly distanced herself from her father after he called Nazi gas chambers a “detail of history.” By May, Mr. Le Pen was suspended from the party, a decision that he appealed to no avail. In August, Mr. Le Pen was categorically expelled from the party he helped found, ostensibly for making the same kinds of comments that had won him votes in the past. Holocaust denial and open racism is out; a defense of a uniquely European culture—a Europe for Europeans, but without the meddling EU to muck things up—is in. The appeal to nationalism is still there, but it has been sublimated and made respectable.It’s worth looking once again at how this positioning plays against the general 2014 Eurobarometer readings. Those that identify by nationality only, without any sense of belonging to Europe, are a natural potential constituency for the far right: those who see themselves in national only terms are more distrustful of EU institutions and tend to see EU integration as a bad thing for their countries, according to Eurobarometer trends. When the economy gets bumpy and Brussels appears particularly ineffective, the euroskeptic pitch resonates. But it’s arguably the “European second” cohort where the real battle for the future of Europe is being waged. The modern far right pulls those people away from what is a weak attachment to the EU by appealing to a more inchoate sense of Europeanness that both transcends, and is under threat from, the bureaucracy in Brussels. Marine Le Pen’s pitch in France, which nets her between 41 and 45 percent in runoff elections according to those recent polls, suggests that her strategy is working.Leftists, on the other hand, base their whole euroskeptic argument in economic terms, and as such are playing on the turf on which Monnet’s dream is succeeding best. Voters see value in the common market and common currency, and a purely contrarian position (“the euro is a bad deal”) is not as resonant. Put simply, Greece’s Lafazanis may be an economic euroskeptic, but he doesn’t have the cloaked nationalist appeal or the anti-immigration worldview to win over votes.And the migrant crisis convulsing Europe these days is only likely to strengthen the allure of the far-right’s pitch, even as Europe’s elites continue to remain obstinately deaf and blind to its appeal. “Our answer [to the migrant crisis] must be in line with our history and our values, in line with what Europe is about,” Europe’s Economic Commissioner Pierre Moscovici said as hundreds of thousands of refugees poured into Euope. “To be European means to care about humanity and to care about human rights. […] When the world and Europe face such a drama, the answer should never be nationalistic. Never to close borders, never to renounce our values. Never.” Alas, fervently wishing for something does not make it so. Just yesterday, Germany “temporarily” exited the Schengen zone and started requiring passport checks on its border with Austria. The far-right is licking its chops as the EU struggles to come up with a coherent response to the refuges crisis.Is an Ever-closer Union Still Possible?The era of EU expansion appears to be over. Though some states are still knocking on the door of Fortress Europe looking to be let in, they are being told not to hold their collective breaths.Meanwhile, others on the inside are plotting their escape. A Grexit was narrowly averted with Tsipras’ most recent capitulation, but still cannot be fully ruled out, especially if the Greek economy doesn’t start showing signs of recovery in the next year. British support for staying in the EU is split (49 percent support staying while 44 percent favor leaving the Union, according to a recent poll) ahead of a public referendum currently scheduled for some time in 2016. Even the Danes are getting in on the act, scheduling a referendum on opting out of common EU justice and home affairs rules for December.Other southern European states are still in economic trouble: Spain’s economy has shown some signs of recovery this summer, but unemployment remains at over 20 percent; Italy is also struggling to cope with its stubbornly high youth unemployment—44.2 percent as of June 2015. In both countries, we are bearing witness to the birth of a permanently scarred generation, a cohort that is likely to have lived through its critical 20s without any relevant job experience, and is likely to be economically worse off for it for the rest of their lives. If they play their cards right and follow Marine Le Pen’s lead, euroskeptic far-right parties will only gain at the polls.And yet, there is still cause for some guarded optimism. For one, despite the skill with which far-right parties have been able to exploit the EU’s weaknesses, their political program still amounts to a cri du coeur and not much besides. Economically, far-right parties across the continent are peddling little more than warmed-over protectionism in an era of unprecedented globalization. As reactionary grousing, it hits all the right notes; as a prescription for a better life in today’s world, not so much. The EU, for all the real pain it has caused with its elite-driven bureaucratic bungling, is itself not the ultimate source of many of the anxieties far-right parties propose to cure. Limiting Muslim immigration might scratch the itch for some voters, but repealing Schengen will not bring unemployment down.For another, among the unrelenting doom and gloom prognostication, it’s all too easy to lose sight of the real successes that the European Union has fostered. Monnet’s dream has kept what was once a war-ridden continent whole, free, and at peace. This is no small feat. Perhaps, in hindsight, the rush to implement the common currency was misguided, its integration uneven and hasty. Nevertheless, research shows that European integration and the common currency has allowed Europeans to experience each others’ countries and cultures more than ever before: more Europeans, particularly the young, study and work in other European countries, speak multiple languages, and find romance outside their own borders. As a result of this cultural mixing for work and pleasure, Europeans today are more aware of each others’ interests, and more empathetic to each others needs than ever before. This is not yet the coherent European civic nationalism Monnet anticipated, but it should not be so readily brushed away either.The young in particular are a key cohort. Europe’s youth face a difficult road ahead—youth unemployment is at staggering highs—but these younger people are also more likely to see themselves as European in some capacity. Europe’s millennials and Generation Z may take the achievements of the European project for granted, but whether they know it or not, these young people are already more European than their parents.This is a pivotal moment in Europe’s history, and mainstream politicians need to seize it. The progress that has been made towards realizing a European identity has occurred during a time of relative prosperity. Politicians across the continent need to prioritize improving the prospects of those who have sat out the last six years unemployed—especially the young. And they must do it together, emphasizing that the future of Europe’s peoples is in cooperation, coordination and openness, not in beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism.In the current climate of economic uncertainty, Europe’s youth are searching for something concrete to hold on to; a vision for the future that speaks to their concerns, lifestyles, and values. The European dream, guided by the EU’s founding principles—democracy, inclusion, economic liberalism—could still fill that void. Monnet’s dream may have its moment yet, but only if European leaders realize that without a vision for the future, there can be no path from the uncertainty of the present.

To further understand how economic decline affects individuals’ sense of belonging, Neil Fligstein and I analyzed Eurobarometer surveys before and after the financial crisis, in 2005 and 2010. In a forthcoming paper in the Journal of European Public Policy, we find that citizens of countries worst hit by the economic crisis—most notably in Greece, Spain, Italy, and Ireland—became more nationalist. Specifically, in countries where GDP fell and debt increased by the largest margins, individuals became more likely to define themselves in national terms, looking to their national governments for protection from worsening economic conditions. This tendency appears to hold across demographic characteristics, political views, or educational backgrounds.But the Eurobarometer data goes only so far. It suggests that the early theories of visionaries like Monnet and of political scientists like Ernst Haas—that economic integration would beget political cooperation, which would in time birth a new ‘European nationalism’—have not panned out. It tells us that the impressively broad and robust-seeming bureaucratic and economic edifice that has been built on the European continent since World War II has yet to put down deep roots in Europeans’ cultural consciousness. It suggests that the European dream is in trouble, especially in today’s febrile political climate, given the strong relationship between economic hardship and a decline in support for European identity.It does not, however, explain how the dream is failing and what its vulnerabilities are. My own research, detailed in a recently published book, has found that economic distress alone has historically not been enough of a motivator for Europe’s voters to wholly embrace an anti-European nationalist politics. However, when economic worries are coupled with concerns about immigration in a broader climate of declining societal trust, people start to look to the political extremes. Other research has shown that generalized hostility towards the EU explains far-right voting over and beyond all other socio-political attitudes, including feelings of ethnic threat from minorities and general xenophobic attitudes.Put those two insights together and you begin to see the broad potential appeal, and staying power, of the new far-right in Europe. Monnet’s dream, for all its grandiloquent promise, has stalled at the economic level. Its successes there are real enough, of course. People understand and appreciate the benefits that a common market and common currency has brought them—51 percent identified the free movement of people, goods and services, and 25 percent identified the euro as among the most positive achievements of the EU in the 2014 Eurobarometer—and this appreciation probably goes part of the way to explaining the attitudes of people who self-identify as national first and European second. Looking across time, the number of these “European second” people has been growing at roughly the same rate as the number of people identifying solely in national terms has been declining. Yet as we shall see, this secondary Europeanness is a weak glue that is relatively easy to pry apart.Greeks Bearing Debts: Euroskepticism In Name OnlyThe Greek financial crisis, which has dominated European news coverage for the better part of the year, was the first high-profile case of where a radical (so-called) euroskeptic party, the left-wing Syriza, came to power and challenged Brussels. United under the anti-EU banner, some far-right parties elsewhere on the continent cheered Syriza’s rise. But assuming that this alliance of opposites means that functional differences between the far-right and far-left in Europe have disappeared would be too much of a simplification. Syriza, for example, is ideologically not opposed to immigration, while the National Front has campaigned on an anti-immigration platform for decades. And as the Greek crisis shows, this missing ingredient makes a big difference.As the financial crisis began to rattle the eurozone in 2008, investors started examining some of the riskier bets they had made in fat times. The Greek government’s outstanding debt in particular started to look unsustainable. Revelations that the Greeks had systematically cooked their books in the past heightened worries. By April 2010, when credit agencies had downgraded Greek debt to junk status, a consensus had emerged: Greece was on its way to defaulting. By May of the same year, the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the IMF—the so-called “Troika”—was offering to step in with what was to be the first of several bailouts, coming in at €110 billion.Greeks, over 90% of whom self-identified either solely as Greek nationals or as Greek nationals first and Europeans second in 2010 according to Eurobarometer, looked to their own government for leadership and protection amid all the turmoil. What they saw instead was their Prime Minister, George Papandreou of the socialist PASOK, getting ready to agree to a draconian set of austerity conditions attached to the bailout money: demands for deep cuts to social programs, including pensions, healthcare, and government salaries, and an increase in taxes.In Papandreou’s defense, he realized early that his room for maneuver was limited. Having adopted the euro, Greece could not devalue its way out of its debt pile as many southern European countries were all too fond of doing in the past. He knew he would have to submit to whatever demands were made of him, or preside over an unprecedented default by his country.But Greece’s voters were having none of it. Protests demanding Papandreou drive a harder bargain began to multiply. The protesters’ logic was not hard to grasp: in the spring of 2010, the rest of Europe was petrified of the knock-on effects that a Greek default would have on the much larger but similarly troubled economies of Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Italy (the rest of the countries that made up the malevolently-invented acronym PIIGS). Greece actually has a few aces up its sleeve, the reasoning went: Papandreou could get a better deal if only he pushed back harder. A massive strike on May 5, 2010 shut down the country and brought hundreds of thousands to the streets of Athens alone. Protests rumbled on for the next two years, as reforms stalled in parliament and the first bailout was supplemented by a second (bringing the total pledged by the troika to €240 billion).Finally, after Papandreou stepped down in late 2011 after nearly losing a vote of confidence, the twin elections of the summer of 2012 (the May ballot failed to produce a government, so a re-vote was scheduled for June) allowed voters to fully express their frustrations with what they saw as a feckless national elite that had failed to protect their interests. The conservative New Democracy took over the top spot in Parliament, but Papandreou’s PASOK didn’t come in second. Instead, voters began rewarding Alexis Tsipras and his Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza), who captured almost 17 percent of the vote in May, and nearly 27 percent of the vote in June. By January of 2015, Tsipras had a mandate to form a coalition government with 36.3 percent support.But Tsipras’ seven-month tenure—he resigned last month after desertions from Syriza followed his caving to the Troika’s austerity demands—was a study in contradictions. In negotiations with the Troika, he insisted on debt forgiveness and was an uncompromising rejectionist of austerity. Yet throughout the drawn-out process, he would periodically insist that he would not allow Greece to default out of the eurozone. A few short weeks after he got a resounding “no” from voters in a referendum on the terms of the bailout deal, Tsipras turned around and agreed to most of the Troika’s terms when the last of Greece’s liquidity began to dry up in June. Although it later emerged that his Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis had set up a contingency plan that would allow the government to issue payments to all taxpayers in what would amount to being a proxy electronic currency, the Greek government chose not to go down the path of Grexit.His newest rival for the leadership of the radical left, Panagiotis Lafazanis, who spun off frustrated Syriza deserters into a new party, is trying to present a stark contrast, vowing to “smash the eurozone dictatorship” and calling for a return to the drachma. But after Tsirpas’s promise and subsequent failure to secure a better deal with the EU, Lafazanis appears to be equally distrusted. At time of writing, his party, Popular Unity, is hovering around the 3 percent threshold for entering parliament.These seeming contradictions, however, ought not puzzle us too much. The Greek crisis was predominantly economically fueled, and the solutions Syriza was proposing were likewise limited to that domain. Though Syriza’s leaders at times stoked nationalist impulses, particularly in vilifying the Germans as latter-day Nazis, they were careful to insist that their beef was with the unreasonableness of European demands, not with the idea of the EU itself.Looking back, it appears as if Tsipras judged that voters wanted to remain in the EU, and were mainly demanding a better deal from Brussels. And it looks like he was right. Though Greece’s voters emphatically rejected the bailout’s terms in what was arguably a rushed and confusingly politicized referendum in early July, public opinion nevertheless continued to back Tsipras even as he concluded his negotiations and accepted the draconian terms of the latest bailout. Though Tsipras’ popularity has taken some hits since the bailout passed parliament, his Syriza coalition, shorn of its most radical left elements, is still running neck-and-neck with New Democracy for the top spot in the upcoming snap elections. It turns out, there was never much evidence that Greek voters had an appetite for the outright rejectionism that many outside observers feared Tsipras would resort to—or that is now on offer by Lafazanis.The Far Right: All Grown UpIt is important to remember, however, that a certain number of Greeks did turn to the extreme right in the 2012 elections: for the first time in Greece’s post-war history, Golden Dawn, a far-right ultranationalist party with a paramilitary bent, entered parliament with 7 percent of the vote. By the January 2015 election, Golden Dawn was the third largest party in the country, albeit with a slightly diminished 6.3 percent support. And there they’ve stubbornly stayed: show Golden Dawn capturing around 6 percent of the vote in the upcoming snap elections set for late September. Golden Dawn’s venomous racist platform, openly fascist ideology, and willingness to use street violence, all appear to create a hard upper-limit for their popularity. Indeed, some studies have convincingly argued that the most successful radical right parties are those that frame their nationalism against the external threat of the EU: far-right parties that hold on to the old openly racist, blood-and-soil rhetoric tend to fail at the polls. It’s a lesson that Europe’s slicker, more modern far-right parties—the likes of which just don’t exist in Greece—have properly internalized.The most successful European far right parties have pitched themselves to voters as protectors of a civic liberal tradition, which they have nevertheless successfully reframed along national lines. In these party narratives, the EU has become a threat to national sovereignty, and non-European Muslim immigrants have become scapegoats for the loss of national values and the threat to liberal democratic ideals. Far right parties have paradoxically become defenders of European values against the encroachment of both non-European foreigners, as well against an effete elite in Brussels that is seen to be undermining European civilization by its commitment to pluralism at all costs. Cultural issues, rather than purely economic ones, have become the key to catapulting the far right into the political limelight.France’s National Front is a case in point. The battle between Marine Le Pen and her father over the control of the party he founded precisely tracks how the far right has retooled itself all across Europe. In April 2015, Ms. Le Pen publicly distanced herself from her father after he called Nazi gas chambers a “detail of history.” By May, Mr. Le Pen was suspended from the party, a decision that he appealed to no avail. In August, Mr. Le Pen was categorically expelled from the party he helped found, ostensibly for making the same kinds of comments that had won him votes in the past. Holocaust denial and open racism is out; a defense of a uniquely European culture—a Europe for Europeans, but without the meddling EU to muck things up—is in. The appeal to nationalism is still there, but it has been sublimated and made respectable.It’s worth looking once again at how this positioning plays against the general 2014 Eurobarometer readings. Those that identify by nationality only, without any sense of belonging to Europe, are a natural potential constituency for the far right: those who see themselves in national only terms are more distrustful of EU institutions and tend to see EU integration as a bad thing for their countries, according to Eurobarometer trends. When the economy gets bumpy and Brussels appears particularly ineffective, the euroskeptic pitch resonates. But it’s arguably the “European second” cohort where the real battle for the future of Europe is being waged. The modern far right pulls those people away from what is a weak attachment to the EU by appealing to a more inchoate sense of Europeanness that both transcends, and is under threat from, the bureaucracy in Brussels. Marine Le Pen’s pitch in France, which nets her between 41 and 45 percent in runoff elections according to those recent polls, suggests that her strategy is working.Leftists, on the other hand, base their whole euroskeptic argument in economic terms, and as such are playing on the turf on which Monnet’s dream is succeeding best. Voters see value in the common market and common currency, and a purely contrarian position (“the euro is a bad deal”) is not as resonant. Put simply, Greece’s Lafazanis may be an economic euroskeptic, but he doesn’t have the cloaked nationalist appeal or the anti-immigration worldview to win over votes.And the migrant crisis convulsing Europe these days is only likely to strengthen the allure of the far-right’s pitch, even as Europe’s elites continue to remain obstinately deaf and blind to its appeal. “Our answer [to the migrant crisis] must be in line with our history and our values, in line with what Europe is about,” Europe’s Economic Commissioner Pierre Moscovici said as hundreds of thousands of refugees poured into Euope. “To be European means to care about humanity and to care about human rights. […] When the world and Europe face such a drama, the answer should never be nationalistic. Never to close borders, never to renounce our values. Never.” Alas, fervently wishing for something does not make it so. Just yesterday, Germany “temporarily” exited the Schengen zone and started requiring passport checks on its border with Austria. The far-right is licking its chops as the EU struggles to come up with a coherent response to the refuges crisis.Is an Ever-closer Union Still Possible?The era of EU expansion appears to be over. Though some states are still knocking on the door of Fortress Europe looking to be let in, they are being told not to hold their collective breaths.Meanwhile, others on the inside are plotting their escape. A Grexit was narrowly averted with Tsipras’ most recent capitulation, but still cannot be fully ruled out, especially if the Greek economy doesn’t start showing signs of recovery in the next year. British support for staying in the EU is split (49 percent support staying while 44 percent favor leaving the Union, according to a recent poll) ahead of a public referendum currently scheduled for some time in 2016. Even the Danes are getting in on the act, scheduling a referendum on opting out of common EU justice and home affairs rules for December.Other southern European states are still in economic trouble: Spain’s economy has shown some signs of recovery this summer, but unemployment remains at over 20 percent; Italy is also struggling to cope with its stubbornly high youth unemployment—44.2 percent as of June 2015. In both countries, we are bearing witness to the birth of a permanently scarred generation, a cohort that is likely to have lived through its critical 20s without any relevant job experience, and is likely to be economically worse off for it for the rest of their lives. If they play their cards right and follow Marine Le Pen’s lead, euroskeptic far-right parties will only gain at the polls.And yet, there is still cause for some guarded optimism. For one, despite the skill with which far-right parties have been able to exploit the EU’s weaknesses, their political program still amounts to a cri du coeur and not much besides. Economically, far-right parties across the continent are peddling little more than warmed-over protectionism in an era of unprecedented globalization. As reactionary grousing, it hits all the right notes; as a prescription for a better life in today’s world, not so much. The EU, for all the real pain it has caused with its elite-driven bureaucratic bungling, is itself not the ultimate source of many of the anxieties far-right parties propose to cure. Limiting Muslim immigration might scratch the itch for some voters, but repealing Schengen will not bring unemployment down.For another, among the unrelenting doom and gloom prognostication, it’s all too easy to lose sight of the real successes that the European Union has fostered. Monnet’s dream has kept what was once a war-ridden continent whole, free, and at peace. This is no small feat. Perhaps, in hindsight, the rush to implement the common currency was misguided, its integration uneven and hasty. Nevertheless, research shows that European integration and the common currency has allowed Europeans to experience each others’ countries and cultures more than ever before: more Europeans, particularly the young, study and work in other European countries, speak multiple languages, and find romance outside their own borders. As a result of this cultural mixing for work and pleasure, Europeans today are more aware of each others’ interests, and more empathetic to each others needs than ever before. This is not yet the coherent European civic nationalism Monnet anticipated, but it should not be so readily brushed away either.The young in particular are a key cohort. Europe’s youth face a difficult road ahead—youth unemployment is at staggering highs—but these younger people are also more likely to see themselves as European in some capacity. Europe’s millennials and Generation Z may take the achievements of the European project for granted, but whether they know it or not, these young people are already more European than their parents.This is a pivotal moment in Europe’s history, and mainstream politicians need to seize it. The progress that has been made towards realizing a European identity has occurred during a time of relative prosperity. Politicians across the continent need to prioritize improving the prospects of those who have sat out the last six years unemployed—especially the young. And they must do it together, emphasizing that the future of Europe’s peoples is in cooperation, coordination and openness, not in beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism.In the current climate of economic uncertainty, Europe’s youth are searching for something concrete to hold on to; a vision for the future that speaks to their concerns, lifestyles, and values. The European dream, guided by the EU’s founding principles—democracy, inclusion, economic liberalism—could still fill that void. Monnet’s dream may have its moment yet, but only if European leaders realize that without a vision for the future, there can be no path from the uncertainty of the present.

Germany Reinstates Passport Controls

Over the weekend, our own Adam Garfinkle wrote a must-read piece on Europe’s migrant crisis, in which he predicted that German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s welcoming embrace of refugees was sure to kick off a reactionary response sooner or later, with one of the likely knock-on effects being the end of the Schengen Zone of passport-free travel. Here’s Adam recounting a set of meetings he had on the continent:

I predicted that within five years Poland will be forced to erect passport control at airports for incoming European flights. (In case you are not aware, dear reader, there are none now. We flew from Berlin to Warsaw by way of Munich, and when one lands there is simply no passport control at all—meaning that any non-EU national who can get into Germany and pay for a ticket to get to Poland can indeed fly to Poland without anyone so much as asking his name or how long he intends to stay.) They all said I was wrong, but just a few days ago look what the Danes did: They basically sealed the border to rail and road traffic from Germany. And they were right to do it.

Well, sooner it is. With unused warehouses, sports arenas, and even Berlin’s iconic Tempelhof airport being converted into temporary camps for the sea of humanity flooding into Germany, Berlin yesterday announced it was instituting passport controls along its border with Austria after institutions in Bavaria began to buckle under the load of processing thousands of new arrivals.

The border closure is temporary and, as such, is technically legal under Schengen, but Germany’s Interior Minister refused to rule out other border closings in the near future. The move may force other countries to follow suit: Austria’s Foreign Minister said, “We have only one option and that is to act in concert with Germany.”Merkel’s open door policy toward the migrants has earned plaudits from around the world but appears to have sown discord at home. The leader of the Bavarian party, which is in coalition with Merkel Christian Democratic Union, attacked the Chancellor in an interview on Friday, saying her decision was “a mistake that will keep us busy for a long time.” Privately, officials close to Merkel concede that they did not anticipate that the Chancellor’s remarks would have such resonance and would encourage more migrants to try to get to Germany.This all sets the stage for contentious meetings of EU Ambassadors slated for later today. A draft four-page memorandum of what the meeting is supposed to achieve has already leaked. Gone is the insistence that any migrant relocation program among the EU’s member states be mandatory; in its place is language about Europe being “committed” to sharing the burden. Also notable is the first mention of the creation of massive new internment camps for “irregular migrants”, to be set up in Italy and Greece.Fortress Europe, here we come.India and Vietnam Flirt with Security Cooperation

India’s Air Force Chief visited Vietnam last week, as New Delhi made yet another move to strengthen military ties with a regional power. The Diplomat picked up the story over the weekend:

The Indian Air Force’s (IAF) chief marshall, Arup Raha, arrived in Vietnam on Thursday, where he was received by Vietnam’s minister of defense, General Phùng Quang Thanh. Raha is in Vietnam for a three-day visit where he will meet with a range of senior Vietnamese defense officials and discuss military cooperation between the two countries. Raha’s visit emphasizes the ongoing strategic convergence between Hanoi and New Delhi. Both India and Vietnam have expanded their defense cooperation in recent months, with high-level discussions about security cooperation becoming relatively routine.

Thanh, according to a report in Vietnam’s Tuoi Tre, “hailed Raha’s visit, considering it a boost to the traditional friendship, mutual understanding and trust between the two countries and peoples, particularly in defense ties.” To date, India and Vietnam haven’t focused specifically on air force cooperation, preferring instead to build their security ties around maritime security. The specifics of Raha’s agenda in Hanoi remain obscure for the moment. In broad terms, Vietnamese reports notes that the Indian air chief’s agenda will be broad enough to address strategic security cooperation between the two countries.

India has asserted itself more aggressively abroad since Prime Minister Modi’s election. Last year, Modi reached out to Taiwan. In March, his government announced a big increase in military spending. And over the weekend, the Indian navy was busy conducting exercises with its Australian counterpart. That effort was organized after the Aussies expressed interest in joining the upcoming MALABAR naval exercise, a landmark trilateral event between Japan, India, and the United States.

India is also enjoying its newfound economic status as what the Wall Street Journal called “the strongest of the weak” among emerging markets. India’s GDP is still a fraction of China’s, but it is increasingly viewed as a relatively stable investment. If India does prosper at the expense of other emerging powers (and that is far from a sure bet), look for New Delhi to take more confident steps to confront Chinese power.September 13, 2015

Is Corporatization the Problem?

Fredrik deBoer, the socialist lecturer at Purdue University who is quickly becoming one of the most interesting commentators on American higher education, has a provocative piece in the New York Times Magazine that attempts to offer a unified theory of what is ailing campus political culture. It’s not, as the right typically argues, left-wing ideological intolerance (though he concedes that this is a problem), nor is it, as the campus left would have it, widespread racism and sexism (though there is progress to be made on this front, too). Rather, deBoer suggests that the real source of the campus insanity that has been circulating in the popular press for the last few years—the trigger warnings, the speech codes, the “Yes Means Yes” rules, the coddling and political correctness—is what he calls corporatization, or “the way universities operate, every day, more and more like corporations.” He continues:

As Benjamin Ginsberg details in his 2011 book, ‘‘The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters,’’ a constantly expanding layer of university administrative jobs now exists at an increasing remove from the actual academic enterprise. It’s not unheard-of for colleges now to employ more senior administrators than professors. There are, of course, essential functions that many university administrators perform, but such an imbalance is absurd — try imagining a high school with more vice principals than teachers. This legion of bureaucrats enables a world of pitiless surveillance; no segment of campus life, no matter how small, does not have some administrator who worries about it. Piece by piece, every corner of the average campus is being slowly made congruent with a single, totalizing vision. The rise of endless brushed-metal-and-glass buildings at Purdue represents the aesthetic dimension of this ideology. Bent into place by a small army of apparatchiks, the contemporary American college is slowly becoming as meticulously art-directed and branded as a J. Crew catalog. Like Niketown or Disneyworld, your average college campus now leaves the distinct impression of a one-party state.

DeBoer is clearly on to something here. Campus bureaucrats, like all bureaucrats, are often more concerned with protecting their institution and advancing their own interests than creating the best outcomes for the people that they serve. Some of what the right sees as left-wing ideological militancy on the part of college administrators—for example, the recent adoption of guilty-until-proven-innocent sexual assault policies at some schools—is actually driven more by a corporate desire to protect the college from bad press than any particular political commitment. (The reverse is also true: some of what campus activists see as right-wing oppression by campus administrators—such as letting athletes off the hook for well-substantiated sexual assaults—has just as much to do with the university’s self-interest as it has to do with the patriarchy). Moreover, the proliferation of administrators who advertise the campus, manage publicity, and cater to their students’ every need is related the decades-long transformation of higher education from a type of public service designed to invigorate American democracy into a private service to be sold in at exorbitant prices.

At the same time, deBoer’s framing of the problem as one of “corporatization” misses an important part of the story. The problems he describes—the explosion of campus administrative positions and the crackdown on campus political freedom—might have something to do with market-oriented changes in higher education, but they have just as much, if not more, to do with very different trends: the intrusion of the federal government into higher education, and the resistance to competition among university employees. Federal spending and regulation has played a large role in driving up the tuition rates that pay for the growing army of campus administrators. Overzealous federal bureaucrats at the Office of Civil Rights have been instrumental in forcing campuses to pass speech codes and sex codes over the last few years. More broadly, the make-work administrative positions that deBoer condemns are of a piece with what we call blue-model employment—secure but inefficient jobs that are rarely available elsewhere outside of the public sector. Moreover, the American Association of University Professors’ resistance to any alterations to the tenure-for-life system drives up costs (by limiting universities’ flexibility to shift professors and resources around) and forces campuses to either hunt for corporate sponsors, hire low-paid adjuncts, jack up tuition still higher, or go hat-in-hand to the federal government.It might be said, then, that campus political culture has gotten so out of whack because the university is at once too corporate and not corporate enough. DeBoer is right that it is too corporate insofar as colleges and universities cave to P.C. activists out of concern for their “brand.” But it is not corporate enough in the sense that so much campus policy is managed and controlled by federal authorities, rather than the schools themselves. The most efficient corporations do not have a business model that relies perpetually on vast federal subsidies, human resources policies subject to the approval of federal officials, large swathes of their budgets devoted to a self-perpetuating class of bureaucrats that contribute very little to their overall mission, and a class of employees (faculty) who can work for life. If universities became “more corporate” in the sense that they were actually able to manage their own harassment policies, rein in inefficient administrators, and compete with one another in a truly competitive market, campus political culture might get healthier in some ways.DeBoer’s argument is a serious one, and worth reading in full. Perhaps his “corporatization” framing will encourage others on the Left to acknowledge the destructive effects of administrative bloat.Mistrust Hangs Over December’s Climate Summit

France’s climate envoy had some cautionary words for the developed world this week, telling Reuters that the world’s developing nations would need to see concrete commitments, and not just reassuring words, in order to sign off on any sort of Global Climate Treaty:

Countries suffering the worst effects of climate change will not be content with empty promises at the Paris summit in December and the meeting could end in failure unless they are satisfied, President Francois Hollande’s envoy has warned. […]

…Nicolas Hulot, Hollande’s Special Envoy for the Protection of the Planet, said countries most at risk from rising sea levels and extreme weather also want firm commitments from richer countries to fund efforts to limit global warming.“I have warned everyone. Words will not be enough. Promises will also not be enough,” he said in his office across the road from the Elysee palace.

Hulot is exactly right. Climate change’s effects are as varied as they are far-reaching, but there are essentially two sides entering negotiations in Paris this December: the developed and the developing world. The former is responsible for most of the emissions up to this point and is best insulated from the effects those emissions are producing. The latter is going to be responsible for most of the emissions going forward (though as we’ve said before, there’s no reason it has to follow the same development model the West trail-blazed, involving energy-intensive industrialization before the transition to an information economy), and is most vulnerable to the negative consequences scientists promise climate change is poised to unleash.

The disparity between responsibilities for and exposure to climate change produced a commitment from the world’s rich countries to pay into a $100 billion climate fund, but so far that purse remains far lighter than promised. It’s in that context that Hulot is telling Reuters that “[i]f the nations that are suffering the most are not reassured, we could be heading towards a clash at the conference.” The French envoy warned that “[c]ountries that are suffering the negative consequences of climate change will no longer feed on promises because they doubt the sincerity of richer nations to honor those promises.”A fog of mistrust will hang over the Paris climate summit—hardly the kind of atmosphere conducive to producing a lasting, binding Global Climate Treaty.Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers