Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 550

November 13, 2015

Admin Is Letting Iran Run Roughshod over Syria

As the Syrian Civil War continues to rage and negotiators meet in Vienna, the AP acknowledges some harsh truths about U.S. policy, which is giving more ground to Iran in Syria:

Searching for a diplomatic path forward, Kerry and other U.S. officials have tamped down demands for Assad’s quick departure and allowed Iran — whom they call the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism — to join the mediation process.

By doing so, Washington has accepted that Tehran can continue wielding influence over Syria, which it has relied on for decades to project power throughout the Middle East. That includes arming anti-Israel and anti-U.S. forces Hamas and Hezbollah, which the U.S. considers terrorist organizations. The shift has occurred although the Obama administration vowed to “redouble” efforts to counter Iran’s regional ambitions.It’s unclear what the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, Iran’s Mideast rival, are getting in return.

The report goes on to examine the dispute over “terror groups”, with the Iranians and Russians pressing to delegitimize opposition to Iran, and the U.S. and its allies pushing back. But even if the U.S. were to get all it wants there, we’d still be negotiating on Iranian terms: Assad would be staying, and the Mullahs would be getting a say in the future of Syria.

Noting this, Omri Ceren wrote in his morning e-mail that:[T]he White House [has made] repeated assurances – made from the evening the JCPOA was announced and repeated throughout the summer – promising to “double down” on “pushback” to Iran’s non-nuclear aggression, if only Congress would sign off on the nuclear deal.

Since then Iran has: launched joint Russian-Iranian military operations in Syria in defense of Assad, test-fired a ballistic missile in violation of UN resolutions, convicted American reporter Jason Rezaian on what are broadly considered to be trumped up espionage charges, seized American citizen Siamak Namazi, seized American permanent resident Nizar Zakka, and launched a “surge” of cyberattacks against Americans who work on Iran issues, and repeatedly called for Israel’s annihilation.But the administration told the Washington Free Beacon earlier this week that it would not pursue new sanctions against Iran. And now the new AP assessment indicates that not only is the Obama administration not pushing back against Iran’s activities, it’s actively integrating Iran into the region in a way that specifically enables Tehran’s “arming anti-Israel and anti-U.S. forces Hamas and Hezbollah.”

So far the record seems to show that rather than marking the end of a policy of regional conciliation of Iran, the nuclear deal is just another step in the attempt to accommodate American policy to Iranian goals. It is also indicative of a retreat in the face of Putin’s thrust into the region. The White House is validating the pre-Deal concerns of its harshest critics, while not making life any easier for itself in the Middle East.

Beijing Takes Control of Pakistan Port

A Chinese state firm officially took control of the port in Gwadar, Pakistan, marking a significant milestone for a deal that has been in the works for a long time. The Diplomat has the latest:

The Chinese firm officially signed a 40-year lease for over 2,000 acres of land in Gwadar, marking a milestone in the implementation phase of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a major bilateral initiative to build transportation and other infrastructure along the length of Pakistan, connecting the country’s Arabian Sea coast with the Himalayan border with China. CPEC was unveiled during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s April 2015 state visit to Pakistan, where Gwadar was high on the agenda.

Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Planning, Development and Reform Ahsan Iqbal handed over the lease to Wang Xiaodao, the vice chairman of China’s National Development and Reform Commission. Gwadar is a designated free-trade zone by the Pakistani government. The designation will last for 23 years. Additionally, because of Gwadar’s location in the restive southern Pakistani province of Balochistan, the Pakistani government has created a protection force for Chinese workers who will be working on CPEC projects, including at Gwadar.

India is watching, of course. And so is the United States, which has its own complicated relationship with Pakistan. Just as the U.S. and its Pacific allies are working to strengthen collaboration in the South China Sea, so too is Beijing looking for strategic partners and opportunities. The lease’s signing is a concrete step towards China’s goal of building a new Silk Road by land and by sea.

As this Bloomberg brief on Beijing’s new five-year plan observes, China expects to rely more and more on maritime trade as domestic demand for refrigerated food and dry goods increases. Gwadar is clearly an important part of the equation.Anti-ISIS Offensive Launched in Iraq

The Kurdish assault on the key Iraqi border city of Sinjar, which started yesterday, appears to have succeeded. Tens of thousands of peshmerga fighters, backed by U.S. air support, entered the center of town and drove hundreds of ISIS fighters out from the city they had occupied more than a year ago, Kurdish leaders announced. The city sits on a key road linking the terror group’s Syrian stronghold of Raqqa to the city of Mosul in northern Iraq, also under ISIS control.

Meanwhile, Iraqi forces announced the start of an offensive against Ramadi, a city of 450,000 located 100 miles west of Baghdad. Iraqi ground forces began “their advance to liberate Ramadi from three directions: the west, the north and the southwest, supported by (the air force) who are currently striking selected targets”, read a government statement broadcast on Iraqi television.General Joseph Dunford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, visited Iraq in late October to help finalize plans for this operation. In testimony to Congress a week later, he hinted that U.S. Special Forces might be used on the ground to aid in the assault.The administration’s rethink on Iraq has been one of the rare promising initiatives in the Middle East recently. Nothing is guaranteed yet; more components of this strategy will have to be unveiled before we can judge whether it’s likely to succeed long term. The Kurds will likely be limited by geographic and ethnic factors, and the Iraqi forces have proven uneven at best. But any day when ISIS is getting pushed back is a good day by us.November 12, 2015

New Yorker Whiffs on Free Speech

A few months after the staff of Charlie Hebdo was murdered by gun-wielding terrorists for mocking Islam and the prophet Mohammed, the cartoonist Garry Trudeau argued that the magazine had “abused” its satirical license by provoking a marginalized group:

Traditionally, satire has comforted the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable. Satire punches up, against authority of all kinds, the little guy against the powerful. Great French satirists like Molière and Daumier always punched up, holding up the self-satisfied and hypocritical to ridicule. Ridiculing the non-privileged is almost never funny—it’s just mean.

This sentiment—that parts of society that progressives consider to be non-privileged should not face criticism or ridicule from groups progressives consider to be privileged—is widely held on some quarters of the left, and it has emerged again in the wake of the free speech controversies at Yale and the University of Missouri. Here’s the New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb making a similar apologia for America’s crusading campus censors:

The freedom to offend the powerful is not equivalent to the freedom to bully the relatively disempowered. The enlightenment principles that undergird free speech also prescribed that the natural limits of one’s liberty lie at the precise point at which it begins to impose upon the liberty of another.

During the debates over the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Senator J. Lister Hill, of Alabama, stood up and declared his opposition to the bill by arguing that the protection of black rights would necessarily infringe upon the rights of whites. This is the left-footed logic of a career Negrophobe, which should be immediately dismissed. Yet some variation of Hill’s thinking animates the contemporary political climate. Right-to-offend advocates are, willingly or not, trafficking in the same sort of argument for the right to maintain subordination.

Cobb’s words are eloquent, but his argument is nonsensical. The “First Amendment fundamentalists” he derides earlier in the piece would readily acknowledge that criminal harassment, threats, and intimidation do not constitute protected expression. But the attacks on free speech that have generated so much national media attention have nothing to do with this kind of conduct. In what sense did the Yale email that questioned whether the university should really be in the business of policing Halloween costumes “impose on the liberty of another”? In what sense are defenders of the University of Missouri journalist who tried to photograph protesters in a public space “trafficking in the same sort of argument for the right to maintain subordination” as a Jim Crow lawmaker?

The most worrisome element of Cobb’s argument, however, is the idea that progressive victimhood hierarchies supersede rights to political advocacy and dissent. Good (read: “disempowered”) groups are entitled to free speech, while bad (read: “powerful”) groups are not, at least when their speech is considered offensive towards the “disempowered.” Not only is this understanding of freedom of speech fundamentally at odds with liberalism, it creates what Ross Douthat has called “an intellectual straightjacket” by “assuming that lines of power are predictable, permanent and clear.”

In fact, as the current campus controversies highlight, clear-cut progressive distinctions between punching up and punching down, between disempowered victim and privileged oppressor, are awfully flimsy and fluid. Cobb accepts Yale students’ claim to victim status because they purport to be fighting bigotry (like insensitive Halloween costumes). But twenty years from now, when these privileged individuals are running our government, our universities, and our financial institutions, it will be much less clear that they are “relatively disempowered” and therefore entitled to be immune from criticism.The Twilight of Communist Party Rule in China

No autocracy has been as successful as the Communist Party of China (CPC) in the post-Cold War era. In 1989, the regime had its closest brush with death when millions of protestors demonstrated in major cities throughout the country, calling for democracy and venting their anger at official corruption. The party was saved only with the help of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), whose tanks crushed the peaceful protestors around Tiananmen and in Beijing on June 4. In the quarter-century since the Tiananmen massacre, however, the CPC has repeatedly defied doomsayers predicting its imminent demise. It has survived the shock of the collapse of the Soviet Union but also weathered the East Asian financial crisis of 1997–98 and the global financial crisis of 2008. Since Tiananmen, the Chinese economy has grown roughly tenfold in real terms. Its per capita income rose from $980 to $13,216 in purchasing power parity (PPP) in the same period, catapulting the country into the ranks of upper-middle income economies.

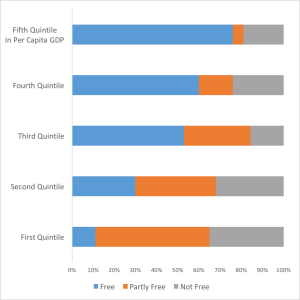

Such a record has understandably led many observers, including seasoned China-watchers, to believe that the CPC has become a resilient authoritarian regime with many inner-strengths that most autocracies lack. Among other things, the CPC is said to have developed an effective process of leadership succession based on established rules and norms, a meritocratic system of selecting capable officials, and a capacity to respond to popular demands. Instead of an ossified regime like the Communist Party of the Soviet Union under Leonid Brezhnev, the CPC has demonstrated a remarkable ability to learn and adapt.1Unfortunately for proponents of the theory of “authoritarian resilience”, their assumptions, evidence, and conclusions have become harder to defend in light of recent developments in China. Signs of intense elite power struggle, endemic corruption, loss of economic dynamism, and an assertive, high-risk foreign policy are all in evidence. As a result, even some of the scholars whose research has been associated with the authoritarian resilience thesis of have been forced to reconsider.2 It has become increasingly clear that the recent developments that have changed perceptions of the CPC’s durability are not cyclical but structural. They are symptomatic of the exhaustion of the regime’s post-Tiananmen survival strategy. Several critical pillars of this strategy—such as elite unity, performance-based legitimacy, co-optation of social elites, and strategic restraint in foreign policy—have either collapsed or become hollow, forcing the CPC to resort increasingly to repression and appeals to nationalism to cling to power.Hence, China’s ruling elites now face the starkest choice since Tiananmen: The post-1989 autocratic crony capitalist development model is dead, and they can either emulate Taiwan and South Korea to democratize and gain an enduring source of legitimacy, or prepare to apply ever-rising repression to maintain one-party rule. How they choose will affect not just China and Asia, but the whole world.Despite popular images of “people power” or the “Arab Spring” revolutions, the single most important source of regime change in authoritarian regimes is the collapse of the unity of the ruling elites. This development is caused principally by the intensification of conflict among the ruling elites over the strategies of regime survival and distribution of power and patronage. Experience from democratic transitions since the mid-1970s shows that, as autocracies confront challenges from social forces demanding political change, the most divisive issue among ruling elites is whether to repress such forces through escalating violence or to accommodate them through liberalization. Should reformers prevail, initial steps toward regime transition, typified by relaxation of political and social control, will follow. If hardliners win the fight, greater repression—but also escalating social and political conflict—will result, at least until the regime faces another crisis that forces it to revisit the question of whether a repressive course is the best strategy.3 Another familiar source of elite disunity is the conflict over the distribution of power and hence the ambit of patronage networks. In more established autocracies, such as post-totalitarian Leninist party-states, this conflict tends to arise when competition for power leads to violations of long-established rules and norms that safeguard a delicate balance of power among ruling elites and their physical security. In many if not most cases—and China is no exception—such violations are committed on behalf of family groupings, and hence represent the repatrimonialization of politics.4In the case of China, the collapse of elite unity turns not on a debate between hardliners and reformers, but on a fight for dominance among hardliners themselves. The initial sign of elite disunity at the top was the purge of Bo Xilai, the high-flying former party chief of Chongqing, on the eve of the 18th CPC Congress in 2012. Later events proved that Bo’s fall was only the prelude to the largest internal housecleaning the party has seen since the Cultural Revolution. After Xi Jinping, the winner of the battle, formally assumed his position as the CPC general secretary and the commander-in-chief of the PLA in November 2012, he launched the most ferocious anti-corruption campaign in recent memory to achieve political supremacy by destroying his rivals. Although Xi’s signature campaign appears to be popular, it has almost overnight dismantled the system the ruling elites painstakingly constructed in the post-Tiananmen era to maintain their unity.Three pillars supported this system. The first was a delicate balance of political power at the top, commonly known as collective leadership, designed to prevent the emergence of another Mao-like leader who could impose his will on the party. Under this system, key policy decisions were made through a process of consensus-building and compromise, ensuring the protection of the interests of the senior leaders and their factions. The second pillar was absolute personal security for top leaders. One of the key lessons from the debacles of the Maoist era was that elite unity is impossible without such security, because only untouchable rulers have the capacity and credibility to negotiate with each other, strike deals, and resolve intra-regime conflict. The third pillar was a system of sharing the spoils of economic growth among the elites, mainly through large and sophisticated patronage networks. To be sure, this system has caused pervasive corruption, but it also has provided incentives for its elites to toil for the regime.Today, less than three years after Xi ascended to the top, this system has been shredded. The equivalent of a “multipolar” world at the top of the CPC regime is now a “unipolar” system; the “collective leadership” has yielded to strongman rule and a decision-making process dominated by Xi. Absolute personal security for the top leaders, defined as sitting or retired members of the Politburo Standing Committee, has also been shattered with the fall of Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the committee and internal security chief who drew a life sentence in 2015 after his conviction on corruption charges. The anti-corruption drive and its accompanying austerity measures have also put an end, at least temporarily, to the practice of sharing spoils among elites, engendering their bitterness and reportedly prompting them to engage in work stoppages as protest. While it is doubtful that Xi’s war on corruption will actually root out corruption, it has succeeded in destroying the post-Tiananmen incentive structure inside the regime.On its own, the transformation of “collective leadership” into “strongman rule” may not necessarily unravel Chinese Leninism. However, the clear initial outcome of this transformation so far is the evaporation of elite unity, the glue that has held together the post-Tiananmen system. Even though there are no overt signs of challenge to Xi’s power within the CPC today, it is a safe bet that his rivals are biding their time, waiting for the right moment to strike back.If elite disunity deteriorates into a political showdown and results in the rejection of the system Xi is trying to construct, there are only two possible outcomes. One is to bring back the corrupt post-Tiananmen system. On the surface, this may seem the most tempting and promising solution, but it will not work: Several of the key underlying conditions that supported the post-Tiananmen system, in particular investment-driven growth and middle-class political acquiescence secured with prospects of ever-rising prosperity, have largely disappeared. If the status quo ante cannot be restored, the CPC will need another way out. While nobody knows what the party will choose, it is worth remembering that, by that time, the party will have tried and exhausted three models of autocratic governance: Maoism (radical communism), Dengism (crony capitalism), and the Xi model (strongman rule). Ironically, the CPC may find itself in the same dire strait as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s: Short of ideas and strategies for maintaining one-party rule in perpetuity, it may be desperate enough to gamble on anything, including democratic reform and political pluralism, as a long-term strategy for making the party a viable force in a China totally transformed by socioeconomic modernization.If elite unity is the glue of the post-Tiananmen system, economic performance, as is commonly acknowledged, is the most important source of popular legitimacy for the ruling party. A quarter century of high growth has bought the CPC a long period of relative social stability and provided it with enormous resources to strengthen its repressive capabilities and buy off new social elites and the urban growing middle-class. However, as the “Chinese economic miracle” is now ending, the second pillar of the post-Tiananmen system is about to collapse as well.Ostensibly, the present sharp Chinese economic slowdown may seem like a natural deceleration after decades of torrid growth. But a closer look at the causes of “the great fall of China” suggests that structural and institutional obstacles, not cyclical ones, are at work and that China is entering a phase of low to moderate economic growth that could imperil the legitimacy of the CPC. Press coverage of Beijing’s recent economic troubles has focused largely on the more visible and dramatic symptoms of the Chinese economic malaise, such as the collapse of a stock market bubble and surprise currency devaluation. However, China’s growth deceleration has much deeper roots.Structurally, China’s rapid growth in the post-Tiananmen era was driven principally by one-off favorable factors or events, and not by the purported superiority of an authoritarian state. Among these factors or events, the most important is the “demographic dividend”, which provided a seemingly endless supply of cheap and able-bodied young workers for China’s industrialization. Besides their low wages, young migrants from rural areas to urban centers can gain an instant and large increase in labor productivity simply by virtue of being paired with operating capital, without need for extensive educational preparation. Consequently, the mere redeployment of the country’s excess rural labor force to factories, shops, and construction sites in the cities can make the economy more productive. According to Chinese data, an urban worker’s productivity is four times higher than that of a rural peasant. In the past three decades, about 270 million rural laborers (excluding their families) have moved to cities and now account for 70 percent of the urban work force. Some economists estimate that about 20 percent of China’s GDP growth in the 1980s and 1990s came from the rural-urban labor relocation.5 But because China’s population is aging rapidly and the mass migration from rural to urban areas has peaked, this one-off favorable structural factor cannot be replicated.Another one-off positive shock that powered China’s growth since Tiananmen was its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. In the 1990s China’s export growth averaged 15.4 percent per annum, thanks to its integration into the global economy. But after its entry into the WTO, China achieved annual growth in exports of 21.7 percent over the period 2002–08. Export-driven growth began to slow after 2011. Between 2012 and 2014, export growth averaged 7.1 percent, a third of the growth in the prior decade. In the first seven months of 2015, exports contracted around 1 percent, the development that probably prompted Beijing to devalue its currency.Perhaps the most troubling aspect of China’s long-term economic outlook is the diminishing return from its investment-driven growth strategy. As a developing country with relatively low stocks of capital, China initially benefited immensely from a sustained rise in its investment rate. In the 1980s, China ploughed an average of 35.8 percent of GDP into factories, infrastructure, and housing. The rate rose to 42.8 percent on average in the 2000s and has reached 47.3 percent since 2010. Such massive increase in investment, accounting for more half of China’s GDP growth, has been the primary engine of economic expansion in the past two and half decades.However, investment-driven growth in the Chinese context has had three negative consequences. One is the diminishing returns on investments, because each incremental increase in output requires more investment, as measured by capital output ratio (the amount of investment needed to produce an additional yuan of GDP). In the 1990s, Chinas capital output ratio was 3.79. In the 2000s, it rose to 4.38. This trend—growth requiring ever-rising investment—is simply not sustainable. China is already investing nearly half of its GDP, an extraordinary number made possible by state control of infrastructure development. The extent of overcapacity and misallocation of capital are equally extraordinary.Another harm inflicted on the economy is that investment squeezes out household consumption (36 percent of GDP in 2013, compared with 60 percent in India), causing a massive structural imbalance and making sustainable growth impossible. That sustainable growth must come from moving away from export-led modalities to domestic market growth, but it cannot set roots with household consumption so artificially low.The final cost of China’s investment-led growth is that much of it has been financed by credit and ploughed into industrial sectors already plagued with excess capacity. With debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 280 percent of GDP today (compared with 121 percent in 2000), risks of a full-blown financial crisis have risen because the largest borrowers—local governments, state-owned enterprises, and real estate developers—have poor repayment capacity due to a narrow tax base (local governments), overcapacity and poor profitability (state-owned enterprises), and a deflating property bubble (real estate developers).If China’s long-term economic woes are purely structural, the country’s prospects are not necessarily dire. Effective reforms could reallocate resources more efficiently to make the economy more productive. But the success of these reforms critically hinges on the nature of the Chinese state and its political institutions. Sustained wealth generation can only take place in states where political power is constrained by the rule of law, private property rights are effectively protected, and there is wide access to opportunity. In states dominated by a small ruling elite, the opposite happens: Those in control of political power become predators, using the coercive instruments of the state to extract wealth from society, defend their privileges, and impoverish ordinary people.6To be sure, the economic policies of the CPC have changed beyond recognition since the end of the Mao era. However, the Chinese party-state has yet to shed its predatory instincts and institutions. Despite rhetoric professing respect for the market and property rights, the actual conduct and policies of the Chinese ruling elites show that they neither respect private property rights nor wish to protect them. The most telling evidence of the absence of their willingness to constrain the predatory appetite and capacity of a one-party state is the top leadership’s undisguised hostility to the idea of constitutionalism, the essence of which is enforceable limits on the power of the state and its rulers. The CPC’s rejection of any meaningful limits on its power, in practical terms, implies that China cannot have truly independent judicial institutions or regulatory agencies capable of enforcing laws and rules. Since genuine market economies cannot function without such institutions or agencies, it is clear that, as long as the party places itself above the law, real pro-market economic reforms are impossible.Many observers argue that a one-party regime is nevertheless capable of implementing pro-market reforms, citing China’s post-Mao history as evidence. Such an argument misses the crucial fact that post-Mao economic reforms, however impressive on the surface, have largely exhausted their potential. Moreover, the Maoist system was so inefficient that even partial reforms could unleash enormous productivity gains, especially in a society where the entrepreneurial energy of the people had been suppressed with totalitarian terror for three decades. Even more importantly, these partial economic reforms have not yet gutted the economic foundations of the CPC rule: state ownership of most productive assets, such as land, natural resources, power-generation, telecom, banking, financial services, and heavy industries. What is holding the Chinese economy back is not its dynamic private sector, but its inefficient state-owned enterprises, which continue to receive subsidies and waste precious capital.7Genuine and complete economic reforms, if actually adopted, will threaten to destroy such foundations. In all likelihood, giving up most of its control over the economy and China’s immense national wealth will result in the organizational collapse of the CPC. The CPC finances and supports its vast organizational infrastructure—party committees and cells through Chinese society—with public funds, the exact amount of which is huge but remains unknown. Much of the funding for the CPC’s organization and activities is provided through the opaque budget of the Chinese state. If the CPC gives up its control of the economy and government spending is made truly transparent, it will no longer have the financial resources to exist. It will become impossible to support the lavish party perks and privileges, such as high-quality health care, large entertainment budgets, free housing, and other allowances, that are provided to officials as rewards for their membership in the elite club.Another catastrophic consequence of complete pro-market reforms would be the destruction of the patronage system the CPC relies on to secure the loyalty of its supporters. The foundation of this system is state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and party-controlled economic bureaucracies and regulatory agencies. If market reforms lead to genuine privatization of these firms (which account for at least a third of the Chinese GDP), the CPC will no longer be able to reward its loyalists with good jobs and contracts, thus risking the loss of their support altogether. Instructively, in the CPC’s blueprint for economic reform released in the fall of 2013, its new leadership reiterated that the party would not abandon the SOEs.Thus, the continuation of China’s predatory and extractive institutions precludes successful, radical, and complete market reforms. The impossibility of the task of constructing a genuine market economy supported by the rule law can be summarized in a wise Chinese proverb, yuhumoupi, or bargaining with a tiger for its skin. The long-term prospects for China’s economic growth, key to the CPC’s survival, are not optimistic. As the era of rapid growth produced by partial reforms and one-off favorable factors or events ends, sustaining China’s growth requires a radical overhaul of its economic and political institutions in order to achieve greater efficiency. But since this fateful step will destroy the economic foundations of CPC rule, it is hard to imagine that the party will actually commit economic, and hence political, suicide. Those unconvinced by such reasoning should count the number of dictatorships in history that willingly gave up their privileges and control over the economy in order to ensure long-term national prosperity.Slouching Toward Repression and NationalismIf long-term economic stagnation were to set in, the Chinese middle class’s support for the status quo will erode. Co-optation of the fast-growing middle-class—another key pillar of the CPC’s post-Tiananmen survival strategy—has been enabled by the past quarter century’s economic boom. China’s secular economic slowdown will undoubtedly reduce opportunities, curtail expectations, and limit upward mobility for members of this critical social group, whose acquiescence to the CPC’s rule has been contingent upon its ability to deliver satisfactory and continuous economic performance.With the evaporation of elite unity, looming economic stagnation, and likely alienation of the middle-class, the post-Tiananmen model is left with only two pillars: repression and nationalism. Contemporary authoritarian regimes, lacking popular legitimacy endowed by a competitive political process, have essentially three means to hold on their power. One is bribing their populations with material benefits, a second one is to repress them with violence and fear, and the third is to appeal to their nationalist sentiments. In more sophisticated and successful autocracies, rulers rely more on performance-based legitimacy (bribing) than on fear or jingoism mainly because repression is costly while nationalism can be dangerous. In the post-Tiananmen era, to be sure, the CPC has employed all three instruments, but it has depended mainly on economic performance and has resorted to (selective) repression and nationalism only as a secondary means of rule.However, trends since Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012 suggest that repression and nationalism are assuming an increasingly prominent role in the CPC’s survival strategy. An obvious explanation is that China’s faltering economic growth is creating social tensions and eroding public support for the CPC, thus forcing the regime to deter potential societal challenge with force and divert public attention with nationalism. There is, however, an equally valid explanation that many observers have overlooked. A survival strategy that depends on delivering economic growth to maintain legitimacy is inherently unsustainable not only because economic growth cannot be guaranteed and ever-rising popular expectations will be impossible to meet, but also because sustained economic growth produces structural socioeconomic changes that, as demonstrated by social science research and histories of democratic transitions, fatally threaten the durability of autocratic rule.Autocracies forced to strike a Faustian bargain with performance-based legitimacy are destined to lose the wager because the socioeconomic changes resulting from economic growth strengthen the autonomous capabilities of urban-based social forces, such as private entrepreneurs, intellectuals, professionals, religious believers, and ordinary workers through higher levels of literacy, greater access to information, accumulation of private wealth, and improved capacity to organize collective action. Academic research has established a strong correlation between the level of economic development and the existence of democracy and also between rising income and probabilities of the fall of autocracies.8 In the contemporary world, the positive relationship between wealth (measured in per capita income) and democracy can be seen in the chart below, which shows that the percentage of democracies (classified as free by Freedom House) rises steadily as income level increases. Partly free countries decline as income rises as well. The distribution of non-democracies, or authoritarian regimes, resembles a U-shape. While more dictatorships can survive in poorer countries (the bottom two-fifths of the countries in terms of per capita income), their presence in the top two-fifths of the countries seems to reject the notion that wealth is positively correlated with democracy. A closer look at the data, however, shows that nearly all the wealthy countries ruled by dictatorships are oil-producing states, where the ruling elites have the financial capacity to bribe their people into accepting autocratic rule.9

Sources: Calculated using income data based on per capita purchasing power provided by the World Bank. Freedom indices provided by Freedom House.

Chinese rulers, if they take a look at the chart, should worry about their medium-to long-term prospects. There are 87 countries with a higher capita income, measured in PPP, than China. Fifty-eight of them are democracies, 11 are classified by Freedom House as “partly free”, and 18 are dictatorships (“not free”, according to Freedom House). But of the 18 “not free” countries with higher per capita income than China, 16 are petro-states (Belarus is included in this group because Russia provides it with significant subsidized energy). The two non-oil states are Thailand (a military dictatorship that overthrew a semi-democracy in 2014) and Cuba (also a Leninist one-party dictatorship). Of the 11 partly free countries, Mexico and Malaysia are significant energy producers while Kuwait and Venezuela are classical petro-states. What should give the CPC leaders even more cause to worry is that Chinese per capita income of $13,216 (PPP) in 2014 is comparable to that of Taiwan and South Korea in the late 1980s, when both began to democratize.10 If the experience of regime transitions in upper middle-income countries, including Taiwan and Korea, were applicable, the CPC should expect rising societal demand and mobilization for political change in the coming decade (some signs of such mobilization can already be detected).

The only implication one can draw from this analysis is that, unless China wants to follow Cuba’s example and maintain a closed economy to ensure the survival of a one-party regime, it will face decreasing odds of holding on to power (provided that China does not miraculously become the equivalent of Saudi Arabia). But since China will never be a petro-state, the CPC may have a chance of long-term survival by introducing some form of competitive politics and becoming a “partly free” regime—a substantial step forward from its Leninist status quo. Alternatively, it can resist even moderate reforms and bet its survival on escalating repression and fueling nationalism.Judging by the policies and measures taken by the current CPC leadership, the party seems intent on betting against history. In the past three years, the party has greatly intensified repression. Among its most notable steps, the CPC has aggressively tightened censorship of the internet, social media, and the press, passed a national security law designed primarily to curtail non-governmental organizations and ensure regime security, destroyed hundreds of church crosses to restrict religious freedoms, strengthened ideological control on college campuses, and arrested dozens of human rights lawyers and civic activists on trumped-up charges. In many ways, the level of repression today is higher than any time since the Tiananmen crackdown.Equally worrisome but more dangerous is Beijing’s escalating appeal to Chinese nationalism. The CPC has all but abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s low-profile and non-confrontational foreign policy in favor of a more muscular external strategy that has brought China on a collision course with the United States. Evidence of Beijing’s renewed appeal to nationalism and its assertive foreign policy can be found in the staging of a first military parade celebrating Japan’s defeat in World War II (even though the CPC played at most a marginal role in the war), a propaganda campaign celebrating the “China Dream” (the essence of which is the revival of China as a great power), a near-explicit demand for parity with the United States (couched in Beijing’s call for a “new type of great power relationship”), relentless cyber-attacks against U.S. government and commercial establishments, and provocations and brinksmanship in the East and South China Seas (establishing a controversial Air Defense Identification Zone over disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and mass land reclamation and island-building in the disputed waters of the South China Sea).If the CPC believes that escalating repression and nationalism will enable it to maintain power during a period of elite disarray, deteriorating economic performance, and heightened social tensions, it must consider the enormous risks and costs of this new survival strategy. Besides taking China backwards, this strategy is unsustainable and dangerous. Repression may work for a while, but autocracies overly dependent on it must be prepared to escalate the use of violence continuously and apply ever-more draconian measures to deter opposition forces. Repression can also be bad for business, as rulers are forced to curtail information flows and economic freedom to ensure regime security. (Indeed, Western firms are already complaining about the inconveniences caused by the Great Firewall.) Raising the level of repression when the economy is sinking into stagnation will strain the CPC’s resources because repression requires the maintenance of an expensive network of informants, secret police, censors, and paramilitary forces. Repression also incurs huge moral costs and could ignite a divisive debate inside the regime. Let’s put the question starkly: Is China really ready to become another North Korea?Manipulating nationalism and muscle-flexing may deliver short-term political benefits, but only at the cost of the CPC’s long-term security. One of the wisest strategic choices made by Deng Xiaoping was to develop friendly ties with the U.S.-led West to accelerate China’s modernization program. In the post-Deng era, Xi’s two predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, also learned a key lesson from the collapse of the Soviet Union: a strategic conflict with the United States would imperil the very survival of the CPC. The costs of a new arms race would be unbearable, and outright hostility in Sino-U.S. relations would destroy the bilateral economic relationship.It is unclear whether the CPC leadership understands the risks of its new and still-evolving survival strategy. If its members are convinced that only this strategy could save CPC rule, now threatened by the collapse of the key pillars of the post-Tiananmen model, they are likely to continue on the present course. Ironically, such a course, if the above analysis is right, is more certain to accelerate the CPC’s demise than to prevent it.1The literature on China’s “resilient authoritarianism” is large. Representative works include Andrew J. Nathan, “Authoritarian Resilience,” Journal of Democracy (January 2003); David L. Shambaugh, China’s Communist Party: Atrophy and Adaptation (University of California Press, 2008).

2Andrew Nathan acknowledged in 2013 that, “The consensus is stronger than at any time since the 1989 Tiananmen crisis that the resilience of the authoritarian regime in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is approaching its limits.” Nathan, “Foreseeing the Unforeseeable,” in Andrew Nathan, Larry Diamond, and Marc Plattner, eds., Will China Democratize? (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013); David Shambaugh published a much-noted long essay, “The Coming Chinese Crackup,” in the Wall Street Journal on March 6, 2015 arguing that the endgame for the CPC regime has begun.3Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (University of Oklahoma Press, 1993); Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).4See Aviezer Tucker, “Why We Need Totalitarianism”, The American Interest (May/June 2015).5Cai Fang Wang Dewen, “Impacts of Internal Migration on Economic Growth and Urban Development in China,” in Josh DeWind and Jennifer Holdaway, eds., Migration and Development Within and Across Borders (The Social Science Research Council, 2008.)6The literature on the predatory state and extractive institutions is vast. The most influential works are Daron Acemoğlu and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail (Crown Publishing, 2012); Douglass North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge University Press, 1990).7The huge inefficiency of state-owned enterprises, as compared with the dynamism of the Chinese private sector, is detailed in Nick Lardy, Markets over Mao: The Rise of Private Business in China (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2014)8Seymour Martin Lipset, “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy,” American Political Science Review (March 1959); Adam Przeworski, Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990 (Cambridge University Press, 2000).9Academic research has also established a strong link between oil and dictatorship. See Michael Ross, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics (April 2001).10Yu Liu and Dingding Chen, “Why China Will Democratize,” Washington Quarterly (Winter 2012).China: Manufacturing Down, Retail Up

Look carefully enough at China’s economic woes and there are some bright spots: The Wall Street Journal reports that despite a pronounced and persistent manufacturing slowdown, retail sales continue to rise. More:

Chinese consumers appear to be weathering the slowdown better than the economy’s traditional growth engines amid weak exports, a manufacturing slowdown and slumping real-estate investment.

A recent McKinsey survey of 1,200 Chinese consumers found that 71% expected their pay to increase this year, and 84% expect to spend more.That dovetails with official data released Wednesday that showed retail sales in October grew 11% from a year earlier, up from September’s 10.9% expansion. Meanwhile, industrial production decelerated to a 5.6% rise from September’s 5.7%. Retail-sales growth has increased modestly in five of the past six months as other economic indicators have weakened.

Because China has been a manufacturing giant for decades, it is easy to base one’s assessment of the country’s future solely on the relative health of heavy industry. But there have been signs that the Chinese economy is moving away from its historical reliance on manufacturing exports and towards one based on services. A rise in retail is further indication that the shift to a services-based economy is happening, because a consumer-based economy will necessarily be a more services-based economy. As the middle class spends more money on toys and clothes, they’ll also spend it on things like entertainment and travel, health, and education. As a result, demand will rise for lawyers, doctors, math tutors, and taxi drivers.

Of course, strong retail sales still aren’t enough to keep everything chugging along, and more reforms—market- and government-driven—will be needed to ensure a smooth transition to China’s new economy.The 1940s Are Back

Many contemporary debates about American social life are premised on the notion that everything is changing—that with the rise of same-sex couples, single-parent households, and pre-marital sex, American family structure looks much different today than it did in the more conservative mid-20th century period. But in at least one important respect, the opposite is true. A new Pew Research Center report shows that, as a growing share of young people choose to live with their parents after turning 18, the multi-generational family is making a comeback:

A larger share of young women are living at home with their parents or other relatives than at any point since the 1940s.

A new Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data shows that 36.4% of women ages 18 to 34 resided with family in 2014, mainly in the home of mom, dad or both. The result is a striking U-shaped curve for young women – and young men – indicating a return to the past, statistically speaking.You’d have to go back 74 years to observe similar living arrangements among American young women. Young men, too, are increasingly living in the same situation, but unlike women their share hasn’t climbed to its level from 1940, the highest year on record.

What accounts for the shift? It probably can’t be attributed entirely to the Great Recession, both because the share of young people living with their parents has been ticking upward for decades and because the improving job market over the past few years hasn’t reversed the trend. In August, we listed a few other factors that might be at play in this story: rising ethnic diversity and immigration (young second-generation Americans are more likely to live with their parents than young people whose families have been in the United States for three or more generations), more liberal attitudes toward sexuality (20 somethings might feel less pressure to get out of their parents’ house if they can bring over romantic partners), and the growing number of single parents (who might be more eager for extra companionship than married couples).

In other words, many of the trends associated with progressivism might be reproducing a family structure from social conservatism’s heyday. We live in interesting times.Greece’s Crisis Afterparty

While the refugee crisis dominates the headlines, an older, more familiar European problem still simmers beneath the surface. The Financial Times reports:

Government offices stayed shut and public transport closed down on Thursday as Greece’s resurgent trade unions staged the first 24-hour general strike since the leftwing Syriza party came to power in January.

Thousands of public sector employees, pensioners and jobless workers shouted anti-austerity slogans as they marched to the Greek parliament in Athens, giving voice to a growing mood of despondency over looming foreclosures on family homes and further pension cuts agreed with creditors under Greece’s €86bn third bailout.

Riot police clashed briefly with a group of protesters throwing petrol bombs and stones in the square outside the parliament building. Three people were detained, according to police.

Meanwhile on Monday, eurozone finance ministers voted to delay a 2-billion-euro bailout payment because the Greek government is failing to implement promised reforms. Deutsche Welle:

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble said Athens had not met “a great number” of commitments agreed to as part of its rescue, following a meeting of eurozone finance ministers in Brussels. He urged the leftist government of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras to deliver.

The package calls on Athens to cut spending, raise taxes and modernize its economy. Greek media reported Monday that key outstanding issues included the details of a plan for taxpayers to settle their arrears, the introduction of VAT on private schools, as well as home foreclosures rules which the Tsipras government insists should protect low-income homeowners.

As we wrote this summer after the Greek crisis had “passed”, the bailout was almost certain to have an afterlife, because the underlying tension between Mediterranean living and German monetary policy had not been resolved. Refugees, euro bailouts, succession movements—European crises continue to mount. And while leaders in Brussels and Berlin have been able to kick the can down the road each time, they don’t seem to have found any long-term solutions yet for the multiple problems plaguing the Continent.

American Sclerosis, Infrastructure Edition

America’s infrastructure is aging, and to the extent that it isn’t updated, built out, and improved upon, it can pose a serious threat to public safety. That’s the message the New York Times wants you to hear:

From coast to coast, the country’s once-envied collection of bridges, dams, pipelines, sewage treatment plants and levees is crumbling. Studies have shown that a lack of investment in public infrastructure costs billions of dollars a year in lost productivity, as people sit in traffic or wait for delayed shipments.

But experts on transportation infrastructure say the economic measures obscure the more dire threat to public safety: Every year, hundreds of deaths, illnesses and injuries can be attributed to the failure of bridges, dams, roads and other decaying structures. […]In recent years, several well-publicized failures of roads, bridges and oil and natural gas pipelines have highlighted the lack of spending on infrastructure and the inability of strapped states to adequately inspect their structures.

This is one of those episodic lamentations and cries of woe over the infrastructure problem in the United States, and it reads like something that could have been written by the PR department of the contracting industry. That’s not to say that the problems covered aren’t real. But this article, which attributes almost all problems to a simple but mysterious lack of money, won’t help readers understand what is going on, much less how it could be fixed. Infrastructure repair is an important American problem, one which is getting worse. But to see why a problem this apparently obvious isn’t being addressed requires an understanding of the sclerosis that afflicts the American political and economic system on so many levels.

First, we need to look at the permitting system. To the Gray Lady’s credit, the piece gets this. Everything takes forever in the U.S., due to years of NIMBY obstructionism, legal review, and on and on. We need a dramatic acceleration in the speed at which our legal and permit systems operate, and we don’t just need that for infrastructure—the clogged arteries of the legal and bureaucratic state hamper business formation and all kinds of public and private activities.The crazy cost structure in the U.S. also bears scrutiny. America’s infrastructure is so hard to fix in part because it is so much more expensive to do stuff here than in many other countries. It’s a bit like our health care system, in that regulatory capture, cronyism, and sweetheart deals involving both business and labor combine to drive up public costs. It ought to be getting cheaper to fix infrastructure—we use materials more efficiently, the machines are more powerful and faster, designs have improved—but costs are instead exploding. Our infrastructure policy, like our health care policy and our education policy, is being held hostage by producer lobbies and cabals. There are some legitimate reasons for higher costs (mostly related to safety and environmental factors), but overall it’s ridiculous that the country can’t afford to repair infrastructure that it built decades ago when we were all much poorer.Finally, we need to acknowledge that policy deadlock reflects political gridlock: The inmates have captured the asylum and the rent seekers control the political process. In every statehouse, in every county seat in America, the businesses and unions who control the building and repairing of expensive pieces of public infrastructure are deeply integrated into the political power structure and have their tentacles into both parties. Again, something similar is true in the other areas of chronic policy failure in the U.S., like health care. The special interests, some “lefty” and some “business friendly”, agree on one thing: The public is a cow to be milked for their mutual benefit.These issues get to the heart of what is wrong with American government today, and they require a sweeping set of reforms that right now our politics seems incapable of providing. That’s too bad; the decay of essential pillars of national health and safety is not a small problem. And the failures of policy in these critical areas has a lot to do with the increasingly angry tone of politics right, left, and center.It may be too much to hope that politicians will solve these problems quickly, but it would be a good start if journalism did a better job of covering some of the most important stories in the United States today.Lincoln v. Obergefell

Dear friends:

The issues we’ve joined are important. In your recent public statement and “Call to Action”, you declare that the recent Supreme Court decision holding that gay couples have the right to marry is “not the law of the land” and should not be treated as such by U.S. elected officials. You repeatedly cite the views of Abraham Lincoln to justify this assertion.My recent essay in The American Interest, “What Would Lincoln Do?”, challenges your argument and particularly seeks to make the case that it’s usually a bad idea to try to recruit Lincoln for contemporary partisan political duty. Several of you have thoughtfully responded, including Matthew Franck in National Review (“David Blankenhorn’s Lincoln: Bent, Folded, Mutilated”) and Hadley Arkes in The Public Discourse (“Recovering Lincoln’s Teaching on the Limits of the Courts—and Giving the News to David Blankenhorn”). I’ve also benefitted from lively exchanges on the topic with my friend Robert George on Facebook and from reading his earlier First Things essay, “Lincoln on Judicial Despotism.” I’m grateful for these replies and exchanges.From my perspective, here’s the nub of our disagreement: I believe that you are urging upon Americans an extremist idea in the name of a revered American who was the opposite of an extremist. By way of keeping our conversation going, let me try to explain—with respect—what I mean.An Extremist IdeaUnless I misunderstand you, your argument extends beyond Obergefell and beyond any particular Supreme Court ruling. You’re proffering a general proposition. You’re articulating a doctrine. You’re interpreting the Constitution. You assert that U.S. officials who sincerely believe that a Supreme Court ruling is unconstitutional (what you also call “lawless”) have both a legal right and a moral obligation to ignore that decision and to refuse to enforce it as public policy.I view this idea as extremist mainly because I’ve seen it up close, in my own life. I know how it looks, sounds, and feels in actual operation, and I know what it can lead to, not to exclude violence.In May 1954, about a year before I was born, the largest newspaper in my home state of Mississippi ran a front-page editorial entitled “Bloodstains on White Marble Steps.” The topic of the editorial was the just-announced U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Court, overturning a previous Court ruling, declared racial segregation in U.S. public schools to be unconstitutional. Elected officials in Mississippi overwhelmingly viewed the Brown decision itself as unconstitutional, or, as they repeatedly put it, “unlawful”, and the editors of the Jackson Daily News agreed, announcing plainly that “Mississippi will not and cannot try to abide by such a decision.” And then they made this prediction: “Human blood may stain Southern soil in many places because of this decision. . .”The prediction turned out to be true. When I was seven years old, in the fall of 1962, with Mississippi’s schools still segregated, the state governor, Ross Barnett, went on television and radio across the state to denounce Brown v. Board of Education in unflinching language—language, in fact, that might be familiar to you—and to rally public support for the doctrine of “interposition”, which stipulates that a U.S. state can lawfully prevent the enforcement of a Federal judicial edict that the state’s leaders and citizens consider to be unconstitutional. Barnett said: “We must either submit to the unlawful dictates of the Federal government or stand up like men and tell them, never!”Toward that end of “standing up like men”, the governor urged his fellow Mississippians to gather in Oxford, Mississippi, the site of the University of Mississippi, to prevent by any means necessary the enforcement of the unlawful judicial decree. Mississippians responded, and on the night of September 29, 1962, two people were killed and over 300 were injured in what amounted to a state-sponsored riot instigated by the governor’s repeated calls to the public to oppose what he viewed as judicial despotism.At the level of constitutional reasoning, it strikes me that what you are calling upon American officials to do today is precisely what Ross Barnett and other Mississippi leaders actually did in 1962. If I’m wrong in this assumption, please correct me.Let’s consider a hypothetical. What if the governor of, say, Idaho, tomorrow ordered the closure of every County Recorder’s Office in the state, on the grounds that having no such agencies at all is preferable to submitting supinely to unconstitutional Federal coercion? You may or may not favor such an action on prudential grounds, but as constitutional reasoning, isn’t such an action of defiance a good example of what you’re arguing that U.S. officials today have every legal right and moral obligation to carry out? (Virginia county officials who in 1959 closed their public schools rather than obey what they sincerely viewed as an unconstitutional Supreme Court order to integrate them certainly saw things exactly this way.)Or what if the state of, say, Arizona tomorrow simply refused to issue marriage licenses to gay couples? And what if, in such a situation, the Federal government were to respond by sending troops to Arizona to make sure that gay couples could get marriage licenses? And if that were to happen, what if the aggrieved citizens of Arizona were to decide to arm themselves and gather in the state capitol to defend, by force if necessary, the true meaning of the U.S. Constitution?Whose side should we be on? The side of the Federal government, which, by your lights, would be seeking to impose a blatantly unconstitutional, illegal act on the people of Arizona? Or should we stand with the people of Arizona who are willing, if necessary, to give their lives for the principle of self-government and the protection of the Constitution?It doesn’t help matters to say, as several of you have said, that while you’d support the state’s right to abrogate the Court’s decision, you would not personally counsel violence as a method of resolving the dispute. It doesn’t matter what you would counsel. Plenty of people counseled Ross Barnett against violence. Plenty of people counseled against the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861, which the attackers also justified on the basis of their sincere interpretation of the Constitution—an interpretation, moreover, that bears remarkable similarities to your own.What matters is not your view of violence, but the political structure of the situation. When our last, best procedures for resolving deep conflict are unilaterally declared by one or both sides to be legally inoperative because unconstitutional, we know from our history that what often emerges to take the place of politics is violence or threats of violence, despite counsel to the contrary. In other words, what is structurally decisive in such situations is an interpretation of the Constitution—which in my understanding is your interpretation—that might as well have been designed to produce irresolvable conflicts, which in turn often lead to violence. Ultimately, it’s an interpretation of the Constitution that allows some of us to declare the legal right and obligation to take the law into our own hands, thereby effectively substituting disorder for order and force for argument in our political life.It’s therefore no coincidence, as the Marxists used to say, that this idea—whether it’s called nullification, interposition, states rights, or opposition to judicial despotism—is so closely linked historically to politically motivated and inspired violence. It’s the idea that led to state-sponsored violence against Cherokees and Christian missionaries in Georgia in the 1830s, when Georgia and the U.S. Supreme Court could not agree on the legality of a Supreme Court decision; precipitated the threat of a Federal military invasion of South Carolina in 1833 during the so-called “Nullification Crisis”; ripped the country into two and led to a devastating Civil War in the 1850s and 1860s; and helped to facilitate, and was used to justify, a terrible stream of violence and brutality in the South in the 1950s and 1960s.That’s what I mean, and all I mean, by describing what you appear to be advocating as an “extremist” idea. It has nothing to do, in my mind, with my substantive disagreement with you on gay marriage. And I don’t mean (simply) that what you’re advocating is a minority or currently unpopular constitutional view. I hold minority views myself. I mean that what you call for has the proven potential to split Americans apart, possibly irrevocably, and to lead, as my hometown newspaper aptly put it, to blood on our soil.In Lincoln’s Name Our exchanges have convinced me that, in my essay, I understated the degree and persistence of Lincoln’s opposition to the Dred Scott Supreme Court ruling of 1857, in which the Court infamously held that African Americans cannot be citizens and that Congress had no power to exclude slavery from the territories. Lincoln detested that decision and viewed it as a threat to the country. The decision shook his faith in an impartial judiciary. He wanted it overturned.More to your point, he refused to accept Dred Scott as a fixed guide to public policy (a “political rule”) for the United States. And by 1862, notwithstanding the absence of either a Constitutional amendment or a reversal of the decision by the Court, Dred Scott as public policy had been effectively nullified by a combination of Lincoln’s leadership, Congressional action, and the exigencies of the Civil War. In my essay, I should have emphasized these points more forthrightly.I also now recognize that, from your perspective, it’s important for us to acknowledge that ignoring or abrogating a Supreme Court decision is not always and certainly not necessarily done for purposes (such as racial segregation) that most Americans today abhor, but can also be done for purposes (such as opposition to slavery) that nearly all Americans today revere. Point taken.At the same time, I believe that your attempt to recruit Lincoln as a spokesperson, symbol, and political champion for the revival of the doctrine of interposition as applied to today’s culture wars is significantly weakened by three important considerations.Chaos and Violence Don’t Teach Us Much About Preventing Chaos and ViolenceThe main American story in the middle and late 1850s is the nation’s rapid slide toward violence and civil war. Substantively, the main cause of the slide was slavery. Constitutionally, the main cause was the breakdown of the only established procedures through which, under our Constitution, painful disagreements among us can be peaceably managed. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise, was a terrible blow to the idea that Congressional compromise can avert civil war. The Dred Scott decision of 1857, arguably the worst Court decision in our history, was a second terrible blow, this time aimed at the very idea of an impartial, rational judiciary.During these years things fell apart; the center could no longer hold; force replaced argument; defiance replaced accommodation. What Lincoln later called the better angels of our nature seemed to desert us. Lincoln struggled under these terrible circumstances with wisdom and courage and skill, but neither he nor anyone could stop the nation’s descent into disorder and violence.Is there really much of anything about Dred Scott, up to and including Lincoln’s response to it, that we should embrace today as a lasting guideline for how to live together peaceably under our Constitution? I don’t think so. I doubt that Lincoln would think so either. The national breakdown of which Dred Scott was both a result and a cause does not demonstrate for us the living how to protect our Constitution. More the opposite.Lincoln Did Not Have a Clear-Cut Doctrine of the JudiciaryIn your replies, you seem to suggest that nearly everything Lincoln ever said about the judiciary adds up to one big and crystal-clear idea, which is principled opposition to what you call “judicial despotism” or the doctrine of “judicial supremacy.” For example, Matthew Franck in his article has compiled many sentences from Lincoln’s speeches and excerpts from Lincoln’s notes to himself and from various other documents. He has drawn detailed exegetical conclusions, inferences, and deductions from these various pieces of text, all in support of his one big thesis about Lincoln’s doctrine of the judiciary.This intellectual method reminds me of a preacher rummaging through the Bible in search of any word, any verse, any interpretation or inference that can help him to reach the conclusion that, at the beginning of his inquiry, he most ardently desired to reach. I question this approach and this conclusion.If Lincoln did aim to articulate a particular, distinctive doctrine regarding the Supreme Court, as you seem to think that he did, what was the name of that doctrine? As you know, when Calhoun and others walked down this same philosophical road, they wrote long constitutional treatises explicating the doctrine of “nullification.” In later years Strom Thurmond, James J. Kilpatrick, Ross Barnett and others embraced and explained at length the related doctrine of “interposition”, which, as I’ve said, seems to me to be the doctrine that you’re embracing in your statement and “Call.”What did Lincoln name his doctrine? Or, for that matter, the doctrine he opposed? In my view, Lincoln didn’t name or clearly define his constitutional doctrine on this subject because he didn’t have one. Let me here repeat that I agree with you that Lincoln refused to defer to the Supreme Court regarding Dred Scott as public policy. That’s an important fact. But I’m hardly alone in arguing that Lincoln, in this as in other areas, was much more pragmatic that doctrinal.For example, unlike some other leading Republicans such as Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln throughout the 1850s accepted, notwithstanding his personal preferences, the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Law. In late 1860, as President-elect, he also proposed the repeal of personal-liberty laws in Northern states that had been passed in order to thwart that widely despised Federal statute. Yet only a few months later, with the U.S. law still in force, Lincoln as President refused to enforce it, thus allowing many slaves mainly from the South but also (and this was obviously more problematic for Lincoln) from loyal border states to attain their freedom by fleeing to Federal army camps. What does this narrative tell us about Lincoln’s constitutional doctrine? Perhaps something, but surely not very much.Similarly, what do Lincoln’s wartime measures effectively repudiating the Dred Scott decision—such as issuing legal documents to African Americans and supporting restrictions on slavery in the territories—tell us about Lincoln’s overall philosophy of the judiciary? The answer again is something, but not very much. Lincoln’s overwhelming priority was to win the war. The effort by us today to extract from his conduct during these months an abstract constitutional doctrine, sufficiently detachable from historical circumstance to be usable off the shelf for whatever current dispute is troubling us, is unlikely to succeed.More broadly, it seems clear that Lincoln’s views on the judiciary changed over time (particularly after Dred Scott) in response to changing circumstances. A balanced view of what he said and did on this topic reveals a man who often equivocated, often seemed to want to things both ways, and often said things that were either contradictory or difficult to understand.Without trying to re-litigate past exchanges between us, let me offer just one example. Responding to the Dred Scott ruling, Lincoln in 1857 says that Supreme Court decisions on Constitutional questions “when fully settled” should control “the general policy of the country” and warns that any alternative to this principle would be “revolution.” Does that sound like a man calling for a wholesale overturning of established notions of judicial review? Or even a man calling for the nullification of a Court decision? And what, pray tell, does that obviously key phrase “fully settled” specifically mean?To the best of my knowledge, Lincoln never makes this clear. I don’t think he ever wanted to make it clear. Trying to save a nation that was tearing itself apart, Lincoln always wanted room to maneuver. He often quipped that “my policy is to have no policy”, and the Lincoln scholar David Donald memorably, and I believe accurately, wrote that Lincoln’s one dogma was an absence of dogma.The doctrinal purists and extremists within his own party—and there were many—never really trusted him. Many despised him. Lincoln’s feelings toward them, however, are revealing. He tells his secretary that these men are “utterly lawless” and “the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with”, but “after all their faces are set Zionwards.” They’re overly zealous and reckless, Lincoln seems to be saying, but they’re walking toward the light. Here, I believe, we get a glimpse into Lincoln’s character and his basic approach to people and politics.In His Character and Political Temperament, Lincoln Was a Consistent Opponent of ExtremismThe key truth of Lincoln’s political life prior to the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861 was that he tried and failed to prevent the breakup of the Union while protecting the Constitution. They key truth of Lincoln’s life from Fort Sumter to his death in 1865 was that he tried and succeeded in restoring the Union while protecting the Constitution as best he could.To me, in either of these periods, it’s very hard to find in Abraham Lincoln a man preoccupied with drawing ideological lines between him and others, or a proponent of the hard-edged, uncompromising position nearly certain to divide and polarize. If, for your purposes today, you want as your spokesperson a political leader from the 1850s who opposed Dred Scott and who also consistently pushed his ideology to extremes and habitually sought out polarization and conflict in the name of doctrinal integrity, there are many qualified candidates from which to choose. But Lincoln is not one of them.Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers