Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 493

February 8, 2016

Pakistan Fights to Protect Chinese-Managed Port

Pakistan’s military has deployed a large, well-equipped force to protect the Chinese-managed port at Gwadar. Reuters:

Securing the planned $46 billion economic corridor of roads, railways and pipelines from northwest China to Pakistan’s Arabian Sea coast is a huge challenge in a country where Islamist militants and separatist gunmen are a constant menace.

The armed forces and interior ministry have sent hundreds of extra soldiers and police to Gwadar, the southern hub of the so-called China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and more are on their way.“Soon we’ll start hiring 700-800 police to be part of a separate security unit dedicated to Chinese security, and at a later stage a new security division would be formed,” Jafer Khan, regional police officer in Gwadar told Reuters.

This story points to a key of both Pakistani and Chinese strategy: crushing the insurgency in the area so that the new, multibillion-dollar Silk Road can reach the port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean.

For its part, Pakistan needs China. With the U.S. increasingly alienated by Pakistan’s pattern of hosting and supporting some of the worst jihadis in the world, China, which is called Pakistan’s “all-weather friend,” is a critical partner for Islamabad. Pakistan’s armed forces desperately need money to keep up their nuclear and conventional weapons competition with India, and China is the best available financier.For China, making the land transport system—from Gwadar, up through Pakistan and Afghanistan, and into western China—work is the key to its strategy to secure its energy supplies and establish Chinese supremacy in Central Asia. China is facing naval challenges and hostile powers to its east (made hostile primarily by China’s own aggressive behavior, but that’s another story). In that context, Pakistan is important to China as a friendly neighbor. Moreover, the new Silk Road presents what some Chinese see as an opportunity to break out of the containment wall they believe the U.S. is trying to build around China.Pakistan’s support for this ambition is worth a lot of money to China, and Pakistan needs money, so this all makes sense to both parties. But the ethnic Baluchis, who inhabit much of the thinly populated territory through which the new Silk Road needs to pass, have been fighting what they see as a brutal, crooked, and ineffective Pakistani government for decades. The Pakistani army has been rather effective nationally of late: According to an independent think tank cited in the Reuters piece, terrorist incidents were down 48 percent last year. But the Baluchi insurgency remains strong, and continues to threaten Pakistani and Chinese assets. These guerrilla nationalist movements are hard to suppress, and there are lots of rumors that India and others with an interest in keeping the Baluchi pot boiling have been helping the insurgents in various ways.Meanwhile, given that a deeper China-Pakistan relationship brings India’s two foreign policy nightmares into closer alignment, expect New Delhi to respond.Reviving an Old Model in a New Way

Can the apprenticeship model make a comeback in the twenty-first century? The Wall Street Journal‘s Anne Kadet offers a look at Floating Piano Factory, a Brooklyn-based company offering both cheap piano tunings to customers and high-tech training for aspiring piano technicians. A taste:

Who, in this digital age, would become a piano tech? You might as well study typewriter repair [ . . . ]

But the Floating Piano apprentice who arrived at my door last week was no Luddite. Tom Erickson is a young composer and sax player who describes the sound of his big band, Flying Dragon, “as if a modern classical or jazz composer was writing a Radiohead song.”It was like no tuning I’ve ever seen. Mr. Erickson used an app to help calibrate the pitch and FaceTime video to share his work with his boss, Eathan Janney, who currently lives in Peru.

The story underscores the way that new technology can help facilitate an “old-fashioned,” but highly effective, arrangement, in which the apprentice learns a difficult skill, the customer gets a piano tuned at around a 50 percent discount, and the master monitors the work online and gets an income while enjoying the freedom and flexibility to live thousands of miles away.

Many skills can be taught as well as or better in apprenticeships than in formal classes at accredited colleges with their high tuitions, regulatory and administrative overloads, and superfluous political agitation. Policymakers should focus on reforming the educational and credentialing systems so that more people can find creative, modern ways to teach and learn specialized skills that are as important as ever in the new economy.America’s Biggest Corn Ethanol Producer Rethinking Future

Corn ethanol’s largest producer—and its biggest cheerleader—is taking a step back and evaluating its operations in the industry. The FT reports:

[L]ess than six years after ribbons were cut, [two corn mills] in Nebraska and Iowa and an older one in Illinois will be reviewed for “strategic options,” [Archer Daniels Midland] disclosed last week — a study that could lead to a sale.

It is a far cry from the times when ADM spent $1.3bn on the mills and lifting its ethanol production capacity to 1.7bn gallons per year. That was a heady time: crude oil prices had cleared $60 a barrel, travellers were burning record amounts of petrol and Washington had just passed a mandate requiring biofuels’ use.But now there has been a reversal of fortunes and the value of those investments in ethanol production is now in doubt. Low oil prices and shifting politics are forcing a reckoning for the US biofuel industry, the world’s largest by production volumes. ADM, a potent ethanol advocate since opening its first plant in 1978, will be a test case.

Corn ethanol production has ballooned over the past decade, kickstarted by the 2007 Renewable Fuel Standard, a law that mandated U.S. refiners start blending ethanol into their products in volumes that increased annually. The idea behind this policy (which, it should be noted is a bipartisan success story: it was signed into law by George W. Bush and truly embraced by President Obama) was to bolster American energy security by sourcing more of our transportation fuel domestically. The whole program was given a green patina by the fact that this ethanol would be derived from crops.

But it’s been clear for many years that the RFS has been nothing but a biofuel boondoggle. Producers like ADM have been frustrated by the fact that fuel can only contain so much ethanol (blending in more than 10 percent ethanol by volume can damage engines in older cars), a phenomenon known in the industry as the “blend wall.” Refiners have complained that they’ve been required to blend more ethanol into their fuels than they’re being supplied, or that they can reasonably manage given that 10 percent blend wall. As a result, refiners have been forced to buy up Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs), credits that have subject to speculation from Wall Street.This mess doesn’t end there, though. By incentivizing the use of more corn crops for biofuels, the RFS has raised global food prices, starving the world’s poor and perhaps even inciting riots abroad. It fleeces American drivers at the pump, and perhaps most damning of all, it isn’t even green (and may be responsible for declining wild bee populations).ADM seems to see the writing on the wall: falling crude oil prices have made ethanol volumes less economically attractive for refiners, and political support in Washington seems to be waning (Ted Cruz won the Iowa caucuses while opposing the RFS). Is this the canary in the corn field we’ve been waiting for?Aleppo, Center of Rebel Power, Besieged

Bashar al-Assad’s forces, bolstered by Russian and Iranian support, have made major advances towards the rebel-held city of Aleppo, as CNN reports:

In the space of a few weeks, the Syrian battlefield has been transformed, the balance of forces pulverized and the prospects for peace talks — already dark — virtually extinguished. Another tide of displaced civilians converge on the Turkish border, trapped by the advance of regime forces.

Last week, the regime of Bashar al-Assad, supported by Iranian and Lebanese Shia militia, severed the main road from Aleppo to the Turkish border, a narrow corridor through which the rebels and NGOs alike moved supplies. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reports that several villages in the area were hit by airstrikes on Sunday.A defining battle for Aleppo, Syria’s largest city before the war, seems imminent. Regime forces and their allies on the ground, supported by Russian bombers in the air, are tightening the noose around the eastern half of the city, still held by a coalition of rebel groups. It’s estimated some 320,000 people still live, or subsist, there — under continual bombardment.

A decisive battle or long siege for Aleppo, the devastated country’s economic center, looks set to change the balance of power in Syria and exacerbate the already-dire refugee crisis. If the regime takes Aleppo, the backbone of the non-ISIS opposition to Assad will be broken. Barring a large-scale intervention by one of the players, this will make the chances of Assad’s regime being overthrown basically nil. Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the United States look on with trepidation, as without the ‘moderate’ rebels, the only remaining check to Iranian ambitions will be ISIS.

The timing of Assad’s offensive also points to the farcical nature of the U.N. mediated peace talks that the Obama administration has staked its hopes on. Just as Russian diplomats were supposed to be negotiating a political solution in Geneva, Russian generals were targeting airstrikes on Assad’s political opponents. Assad and Putin appear to be betting on Western and Arab timidity as they consolidate his power. Even the ongoing flood of refugees benefits Assad, as Sunnis and other ethnic and religious minorities flee his territory and minimize possible sources of dissent in the war-torn wasteland he hopes to once again rule. If he can eliminate the Syrian opposition and make the Syrian war a choice between ISIS and himself, the devil we know might be here to stay.Kerry has apparently been on the phone with Lavrov as many as five times a day, frantically trying to negotiate a “common approach” to Syria. Somehow, the subject of a Russia-backed Assad offensive that would crush the rebels and collapse the peace talks never quite came up. Maybe the answer is to have six, seven, or eight calls with Lavrov a day? Clearly, for some in the administration, the problem is still that we aren’t negotiating enough with Russia.UAE to Join the Party in Syria?

A few days after Saudi Arabia announced it was open to sending ground troops to Syria, the United Arab Emirates may be joining the party. Reuters reports:

Asked whether the UAE could be expected to send ground troops to Syria, and if so under what circumstances, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash said:

“I think that this has been our position throughout … that a real campaign against Daesh has to include ground elements,” he said, referring to Islamic State’s name using the Arabic acronym.[..]Gargash said that any potential supply of troops would not be particularly large.

The Emiratis have several motives here. Firstly, they will back the Saudis’ play, should Riyadh choose to make one, because a close relationship with the Saudis is a pillar of the current Emirati foreign policy. Like the Saudis, the Emirati leadership hates and fears the Iranians and their regional aggression. If Emirati advisors, spotters, and planes (the UAE air force is excellent) can help with a serious coalition effort in Syria, then the UAE will probably see that as a core interest worth pursuing.

But the missing piece is the United States—which has been conspicuously absent in Syria. “Of course an American leadership in this effort is a pre-requisite,” the Emirati Foreign Minister declared. As there’s precious little chance of that before the next election, the Emirati remarks may be seen in some ways as laying down a marker: Any future Administration will be have to face the reality that this Sunni Arab ally is prepared to enter the fight only if the U.S. assumes a leadership role.But that’s a year off—and in the meantime, the Iranians and Syrians are making it clear they want no outsiders in their butcher’s shop. LA Times :At a news conference in Damascus, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Moallem declared that any foreign forces intervening against the government would not come out alive.

“Those who launch an aggression against Syria will return in wooden boxes, be they Saudis or Turks or anyone,” Moallem told reporters.[..]In Tehran, the head of the Revolutionary Guard mocked Riyadh, saying the kingdom lacked the resolve to fight in Syria.

And if Iran were to get involved in a conflict with the Saudis and Emiratis as well, would the Assad regime’s other ally, Russia, get drawn in too? And, if so, what would Washington do if two of its most prominent allies were to wind up in a shooting war with the Russians? What if Turkey, a NATO member and co-sponsor with Riyadh of the Sunni resistance forces, becomes embroiled as well? American foreign policy has been activist for decades in the Middle East not for the fun of administering local quarrels, but precisely to avoid this sort of scenario where a security vacuum brings more and more powers into conflict. Alas, it appears that lesson may have to be relearned—let’s just hope the cost of doing so is manageable.

DPRK Missile Launch Empowers Regional Hawks

The U.N. Security Council condemned North Korea’s Sunday morning missile launch, but it’s not yet clear what concrete actions, if any, the Council will take. CNN:

At an emergency meeting Sunday, members of the U.N. Security Council “strongly condemned” the launch and reaffirmed that “a clear threat to international peace and security continues to exist, especially in the context of the nuclear test.”

Security Council members have previously threatened “further significant measures” if there was another North Korean launch and now will “adopt expeditiously a new Security Council resolution with such measures in response to these dangerous and serious violations,” according to a statement read by Venezuela’s ambassador to the United Nations after the meeting.

China could use its veto to block any Security Council sanctions on the DPRK. Yet that power is more of a burden than a blessing for Beijing, which has to balance its desire to limit both the U.S. military presence in the region and the hawkishness of its neighbors against its commitment to Pyongyang. Indeed, the most important consequence of the launch could be the deployment in South Korea of a missile defense system developed and managed by the United States. A spokeswoman in Beijing said China is “deeply concerned” by reports that Seoul and Washington are planning talks on the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) system.

Sanctions (should they be proposed) and a missile defense system are not the only possible consequences of the missile launch. By scaring everybody and making cooperation with the U.S. and Japan look more attractive, North Korea’s move gives the current South Korean government a big boost in its efforts to handle the fallout over last December’s “comfort women” deal. Pyongyang’s bad behavior (and Beijing’s inability and/or refusal to control it) pushes politics in both South Korea and Japan to the right.

The Great Stall

The Republic of Korea and Taiwan are the only economies of appreciable size to have transformed themselves from low-income to high-income status inside two generations. China has already matched, if not surpassed, the speed of the earlier part of these two far smaller economies’ journey. The biggest question, not only in global economics but arguably also in world politics, is whether China will finish what it has successfully begun, or crash along the way. The answer is that the obstacles ahead are formidable. China might overcome them. But it is also imaginable that it will fail to do so, or, at least, that the journey will take longer and be more difficult than many now imagine.

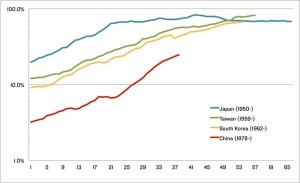

The stakes are very high. If China were to succeed even partially, its economy would be bigger than those of the United States and the European Union combined. If its political system were to remain largely unchanged, the world’s largest high-income country would then not be a democracy, unlike all the others. This would partially reverse the triumph of liberal democracy, hailed at the end of the Cold War.1The journey that lies ahead for China is to become a high-income society. Other societies have achieved prosperity merely by exporting valuable commodities. But that is not development. It is also not a path open to China. While China has used—indeed, abused—its endowment of natural resources, particularly water, air and fossil fuels, during its period rapid economic growth, these resources have always been far too limited to generate even temporary prosperity for so huge a country. Indeed, the abuse of its resources is now creating significant challenges of environmental degradation.As was true of South Korea and Taiwan (and Japan before them), China’s most valuable resource is its hard-working, increasingly well-educated and enterprising people. In the course of their development, the other East Asian economies transformed the structure, sophistication, and size of their economies and, in the process, the quality of the labor force itself. This has also been China’s path.Hong Kong and Singapore managed to do much the same thing. But they are just city-states, with populations of seven and five million, respectively. South Korea, with fifty million people, and Taiwan, with 23 million, had to manage the challenges of urbanization in much the same way as China. With a population of 1.4 billion, China is in another class altogether. Indeed, in respect of size, only India is comparable. But from the economic point of view, what China has achieved since 1978 can indeed be compared with what South Korea achieved after its reforms in the early 1960s. Yet it is also important to note one possibly decisive difference: Western powers, notably the United States, wanted South Korea and Taiwan (and Japan and West Germany before them) to succeed because they were dependencies and allies during the Cold War. The West is far more ambivalent, if not yet determinedly hostile, to China’s ambitions.So, what is the journey that lies ahead? What are the main obstacles in China’s way? What might its leaders do in response?The Journey AheadThe best measure of the standard of living generated by an economy is gross domestic product at purchasing power parity.2 Relative GDP per head at purchasing power parity is also the best available indicator of opportunities to raise living standards by catching up on the productivity levels in more advanced economies. As the most productive of the large economies since the late 19th century, the United States has long been the benchmark. In 1962, South Korea’s real GDP per head (at PPP) was a little under 10 percent of U.S. levels (see figure 1). Just over fifty years later, it had risen to close to 70 percent. At that point, South Korea’s GDP per head had also caught up with Japan’s, whose relative GDP per head had been falling since the early 1990s. South Korea’s real GDP per head rose at a trend rate of just over 6 percent a year between 1962 and 2015. But this should be divided between the era of ultra-high growth between 1962 and 1997, when real GDP per head rose at a trend annual rate of just over 7 percent, and the era of merely fast growth between 1998 and 2015, when real GDP per head rose at a trend rate of 4 percent. The dividing line between these two periods was the Asian financial crisis. As is often the case with such crises, this marked a turn for the worse in South Korea’s growth rate.Since the policy of “reform and opening up” began under Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China’s GDP per head at PPP is estimated to have risen from just 3 percent of U.S. levels to 25 percent. In 1978, China was not only relatively far poorer than South Korea had been in the early 1960s, when the latter’s reforms began; it was even absolutely poorer: China’s real GDP per head in 1978 was half that of South Korea in 1962. It took a quarter of a century of fast growth before China’s real GDP per head reached the same position, relative to the U.S. economy, as South Korea already enjoyed in 1962. It took another 13 years for China’s GDP per head to reach a quarter of U.S. levels, which South Korea achieved in the mid-1980s. Between 1978 and 2015, China’s real GDP per head rose at a trend rate of 7.5 percent, slightly faster than in South Korea between 1962 and 1997.In absolute terms, however, China became as rich as today’s South Korea already in the early 1990s. The fact that U.S. GDP per head itself continues to rise explains the difference between China’s relative and absolute performances. China is chasing a moving target. Opportunities are increasing as more new ideas are put into practice in the world’s most advanced economies. This means that, over time, a given income per head, relative to the U.S. economy, implies a higher absolute income.If China were to match South Korea’s success in catching up on U.S. GDP per head, after the latter’s GDP per head reached a quarter of U.S. levels, it would take China roughly another three decades. Because China started off relatively (and absolutely) much poorer than South Korea, it would then have taken seventy years to achieve what South Korea managed in a little more than half a century.Obstacles to Completing the JourneyThis is certainly an imaginable future. But it is also an unlikely one (though certainly not inconceivable), because China confronts at least five interconnected obstacles to continued progress. Some of these obstacles threaten to slow China’s growth sharply.First, under relatively conservative assumptions about the prospective growth of U.S. real GDP per head (about 1 percent a year), achieving what South Korea did would imply growth of more than 4 percent a year in real GDP per head over another three decades. Regardless of past performance, it’s questionable whether China can sustain such a high rate of economic growth.In an important recent piece, Lant Pritchett and Lawrence Summers of Harvard University conclude: “History teaches that abnormally rapid growth is rarely persistent, even though economic forecasts invariably extrapolate recent growth. Indeed, regression to the mean is the empirically most salient feature of economic growth.”3 In simpler terms, this means that it is far more likely than not that fast growth will slow toward the world average. Such slowdowns have been very common. Indeed, South Korea’s performance was quite extraordinary, as China’s has been, at least so far. One must not casually assume that the extraordinary will continue. That hope has delivered many a disappointment. Moreover, the rapid ageing of the Chinese population will make sustaining high growth of GDP per head even more difficult, since its population of working age is set to grow significantly more slowly than its overall population.Second, if China were to achieve the envisaged growth, its economy would also expand roughly five-fold over the next generation. Given the already huge economic size and limited domestic resources of China, this would put substantial strain on the world’s environmental and economic “carrying capacity.” China’s population is, after all, substantially larger than that of all of today’s high-income countries combined. One must imagine huge improvements in the supply and use of scarce natural resources, not just by China, but by the rest of the world too. At some unpredictable point, environmental constraints might assert themselves. This might not halt economic growth, but it could slow it substantially relative to what small countries such as South Korea have been able to achieve.Another set of constraints could be the capacity to accommodate such a huge shift in relative economic and geopolitical weight. All sorts of stresses would emerge in China’s relations with neighbors, in its relations with other powers, in the absorptive capacity of world markets, in the global monetary and financial systems, and in global institutions. In the past, such huge shifts in relative power have destabilized the world with devastating results, at least in the medium term.Third, it is unwise to assume that China will remain politically stable or, if it does, that it will achieve the improvements in the quality of governance needed by a sophisticated high-income economy. Professors Pritchett and Summers note, pointedly, that “salient characteristics of China—high levels of state control and corruption along with high measures of authoritarian rule—make a discontinuous decline in growth even more likely than general experience would suggest.”Unlike all other high-income countries, China is extremely authoritarian. South Korea was also authoritarian (though not communist, of course) at roughly the same point in its economic development as China is today. But South Korea changed in the late 1980s and 1990s. The resultant upheaval was substantial. Something similar might lie ahead for China. Xi Jinping’s current crackdown, including his anti-corruption campaign, suggests that he fears such a possibility. But his actions—including the fear he must be generating among millions of officials—might prove counterproductive, and even bring about the instability he fears.China’s governance indicators also fall far short of what would be expected of a high-income country. According to the World Bank, the country ranks in the fifth percentile of all countries (from the bottom) in voice and accountability, in the thirtieth percentile in political stability and absence of violence, in the 66th percentile in government effectiveness, in the 45th percentile in regulatory quality, in the 43rd percentile in the rule of law, and in the 47th percentile in control of corruption. Except in voice and accountability, this record is far from poor. But South Korea, in contrast, is now in the 69th percentile in voice and accountability, 54th percentile in political stability and absence of violence, 87th percentile in government effectiveness, 84th percentile in regulatory quality, 81st percentile in rule of law and 87th percentile in control of corruption.In sum, China needs a great deal of improvement in governance if it is to sustain high levels of economic growth over an extended period. It is doubtful whether any country in which the Communist Party rules as an absolute sovereign can achieve the necessary improvements. Certainly, this has not happened anywhere else. That is why communism collapsed in so many countries in the late 1980s and early 1990s.Moreover, a serious slowdown in growth might well catalyze political unrest, instability, and then a crackdown. The suppression of the Tiananmen Square protest worked, at least from the economic point of view, in 1989. But it is far from clear that such a policy would work as well now. China’s current opportunities are very different. It now has a far more advanced and internationally engaged economy, dependent on rapidly rising technological and economic sophistication.Fourth, China is either at or close to the “Lewis turning point,” at which the labor market starts to tighten as the pool of underemployed rural labor dries up. The sharpness of this turning point is likely to be exacerbated in China’s case by the effects of the longstanding (and only recently modified) one-child policy.The Lewis turning point is named after the Nobel-laureate economist Arthur Lewis, who thought the pattern of economic development should be analyzed in relation to the abundance of surplus agricultural labor. Before the surplus disappears, real wages will be stagnant and growth will be driven to a significant extent by increased employment. After the surplus disappears, growth of employment will necessarily slow, real wages will rise rapidly, profitability will be squeezed and economic growth will become more dependent on investment and innovation and less on the continued transfer of surplus labor from low-productivity agriculture to high-productivity urban activities.Whether China has already passed the Lewis turning point is open to debate, since its rural population is still almost half of the total (according to World Bank figures). But China already shows two symptoms of having passed that point. First, real wages have been rising rapidly since the turn of the millennium.4 Second, the trend rate of real economic growth has slowed sharply toward 7 percent (and probably even less, in reality) since 2012. While this is still fast growth, it is well below the previous rate of 10 percent a year or more (See figure 2). Xi Jinping even talks of a “new normal.” But getting smoothly from the old normal of 10 percent growth and cheap labor to a new normal of 6.5 percent growth (or less) and ever-more expensive labor is tricky. When a bicycle slows, it becomes more likely to topple over.

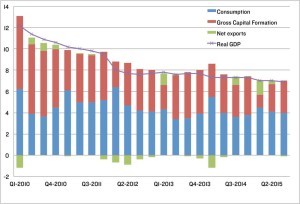

South Korea’s real GDP per head rose at a trend rate of just over 6 percent a year between 1962 and 2015. But this should be divided between the era of ultra-high growth between 1962 and 1997, when real GDP per head rose at a trend annual rate of just over 7 percent, and the era of merely fast growth between 1998 and 2015, when real GDP per head rose at a trend rate of 4 percent. The dividing line between these two periods was the Asian financial crisis. As is often the case with such crises, this marked a turn for the worse in South Korea’s growth rate.Since the policy of “reform and opening up” began under Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China’s GDP per head at PPP is estimated to have risen from just 3 percent of U.S. levels to 25 percent. In 1978, China was not only relatively far poorer than South Korea had been in the early 1960s, when the latter’s reforms began; it was even absolutely poorer: China’s real GDP per head in 1978 was half that of South Korea in 1962. It took a quarter of a century of fast growth before China’s real GDP per head reached the same position, relative to the U.S. economy, as South Korea already enjoyed in 1962. It took another 13 years for China’s GDP per head to reach a quarter of U.S. levels, which South Korea achieved in the mid-1980s. Between 1978 and 2015, China’s real GDP per head rose at a trend rate of 7.5 percent, slightly faster than in South Korea between 1962 and 1997.In absolute terms, however, China became as rich as today’s South Korea already in the early 1990s. The fact that U.S. GDP per head itself continues to rise explains the difference between China’s relative and absolute performances. China is chasing a moving target. Opportunities are increasing as more new ideas are put into practice in the world’s most advanced economies. This means that, over time, a given income per head, relative to the U.S. economy, implies a higher absolute income.If China were to match South Korea’s success in catching up on U.S. GDP per head, after the latter’s GDP per head reached a quarter of U.S. levels, it would take China roughly another three decades. Because China started off relatively (and absolutely) much poorer than South Korea, it would then have taken seventy years to achieve what South Korea managed in a little more than half a century.Obstacles to Completing the JourneyThis is certainly an imaginable future. But it is also an unlikely one (though certainly not inconceivable), because China confronts at least five interconnected obstacles to continued progress. Some of these obstacles threaten to slow China’s growth sharply.First, under relatively conservative assumptions about the prospective growth of U.S. real GDP per head (about 1 percent a year), achieving what South Korea did would imply growth of more than 4 percent a year in real GDP per head over another three decades. Regardless of past performance, it’s questionable whether China can sustain such a high rate of economic growth.In an important recent piece, Lant Pritchett and Lawrence Summers of Harvard University conclude: “History teaches that abnormally rapid growth is rarely persistent, even though economic forecasts invariably extrapolate recent growth. Indeed, regression to the mean is the empirically most salient feature of economic growth.”3 In simpler terms, this means that it is far more likely than not that fast growth will slow toward the world average. Such slowdowns have been very common. Indeed, South Korea’s performance was quite extraordinary, as China’s has been, at least so far. One must not casually assume that the extraordinary will continue. That hope has delivered many a disappointment. Moreover, the rapid ageing of the Chinese population will make sustaining high growth of GDP per head even more difficult, since its population of working age is set to grow significantly more slowly than its overall population.Second, if China were to achieve the envisaged growth, its economy would also expand roughly five-fold over the next generation. Given the already huge economic size and limited domestic resources of China, this would put substantial strain on the world’s environmental and economic “carrying capacity.” China’s population is, after all, substantially larger than that of all of today’s high-income countries combined. One must imagine huge improvements in the supply and use of scarce natural resources, not just by China, but by the rest of the world too. At some unpredictable point, environmental constraints might assert themselves. This might not halt economic growth, but it could slow it substantially relative to what small countries such as South Korea have been able to achieve.Another set of constraints could be the capacity to accommodate such a huge shift in relative economic and geopolitical weight. All sorts of stresses would emerge in China’s relations with neighbors, in its relations with other powers, in the absorptive capacity of world markets, in the global monetary and financial systems, and in global institutions. In the past, such huge shifts in relative power have destabilized the world with devastating results, at least in the medium term.Third, it is unwise to assume that China will remain politically stable or, if it does, that it will achieve the improvements in the quality of governance needed by a sophisticated high-income economy. Professors Pritchett and Summers note, pointedly, that “salient characteristics of China—high levels of state control and corruption along with high measures of authoritarian rule—make a discontinuous decline in growth even more likely than general experience would suggest.”Unlike all other high-income countries, China is extremely authoritarian. South Korea was also authoritarian (though not communist, of course) at roughly the same point in its economic development as China is today. But South Korea changed in the late 1980s and 1990s. The resultant upheaval was substantial. Something similar might lie ahead for China. Xi Jinping’s current crackdown, including his anti-corruption campaign, suggests that he fears such a possibility. But his actions—including the fear he must be generating among millions of officials—might prove counterproductive, and even bring about the instability he fears.China’s governance indicators also fall far short of what would be expected of a high-income country. According to the World Bank, the country ranks in the fifth percentile of all countries (from the bottom) in voice and accountability, in the thirtieth percentile in political stability and absence of violence, in the 66th percentile in government effectiveness, in the 45th percentile in regulatory quality, in the 43rd percentile in the rule of law, and in the 47th percentile in control of corruption. Except in voice and accountability, this record is far from poor. But South Korea, in contrast, is now in the 69th percentile in voice and accountability, 54th percentile in political stability and absence of violence, 87th percentile in government effectiveness, 84th percentile in regulatory quality, 81st percentile in rule of law and 87th percentile in control of corruption.In sum, China needs a great deal of improvement in governance if it is to sustain high levels of economic growth over an extended period. It is doubtful whether any country in which the Communist Party rules as an absolute sovereign can achieve the necessary improvements. Certainly, this has not happened anywhere else. That is why communism collapsed in so many countries in the late 1980s and early 1990s.Moreover, a serious slowdown in growth might well catalyze political unrest, instability, and then a crackdown. The suppression of the Tiananmen Square protest worked, at least from the economic point of view, in 1989. But it is far from clear that such a policy would work as well now. China’s current opportunities are very different. It now has a far more advanced and internationally engaged economy, dependent on rapidly rising technological and economic sophistication.Fourth, China is either at or close to the “Lewis turning point,” at which the labor market starts to tighten as the pool of underemployed rural labor dries up. The sharpness of this turning point is likely to be exacerbated in China’s case by the effects of the longstanding (and only recently modified) one-child policy.The Lewis turning point is named after the Nobel-laureate economist Arthur Lewis, who thought the pattern of economic development should be analyzed in relation to the abundance of surplus agricultural labor. Before the surplus disappears, real wages will be stagnant and growth will be driven to a significant extent by increased employment. After the surplus disappears, growth of employment will necessarily slow, real wages will rise rapidly, profitability will be squeezed and economic growth will become more dependent on investment and innovation and less on the continued transfer of surplus labor from low-productivity agriculture to high-productivity urban activities.Whether China has already passed the Lewis turning point is open to debate, since its rural population is still almost half of the total (according to World Bank figures). But China already shows two symptoms of having passed that point. First, real wages have been rising rapidly since the turn of the millennium.4 Second, the trend rate of real economic growth has slowed sharply toward 7 percent (and probably even less, in reality) since 2012. While this is still fast growth, it is well below the previous rate of 10 percent a year or more (See figure 2). Xi Jinping even talks of a “new normal.” But getting smoothly from the old normal of 10 percent growth and cheap labor to a new normal of 6.5 percent growth (or less) and ever-more expensive labor is tricky. When a bicycle slows, it becomes more likely to topple over.

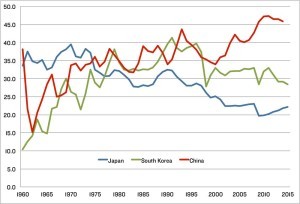

Fifth and most pressing, the economy now attempting to make this transition is, in the words of former Premier Wen Jiabao, “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.” But the problems in this regard are much greater than when Mr. Wen first said this, about a decade ago. While he talked about the unbalanced economy, Mr. Wen’s government allowed the imbalances to grow further right up to the end of his term in 2012. These imbalances are far greater than in other East Asian economies, such as Japan or South Korea, at comparable stages of development.There exist at least three significant dimensions to China’s lack of economic balance: Its growth has become far too reliant on investment; its internal debt has grown unsustainably fast; and its national (not just household) savings rate is far too high to be absorbed productively at home. Let us consider each of these imbalances.The most important fact about China’s current pattern of growth is its dependence on investment as a source of supply and demand. This has been particularly true since 2000. Since then the share of gross capital formation in GDP rose from 35 percent—not an exceptional level for a fast-growing east Asian economy—to almost 50 percent, which is far higher than during the periods of fast growth of Japan and South Korea (see figure 3). This extraordinarily high rate of investment has implications for both demand and supply.

Fifth and most pressing, the economy now attempting to make this transition is, in the words of former Premier Wen Jiabao, “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.” But the problems in this regard are much greater than when Mr. Wen first said this, about a decade ago. While he talked about the unbalanced economy, Mr. Wen’s government allowed the imbalances to grow further right up to the end of his term in 2012. These imbalances are far greater than in other East Asian economies, such as Japan or South Korea, at comparable stages of development.There exist at least three significant dimensions to China’s lack of economic balance: Its growth has become far too reliant on investment; its internal debt has grown unsustainably fast; and its national (not just household) savings rate is far too high to be absorbed productively at home. Let us consider each of these imbalances.The most important fact about China’s current pattern of growth is its dependence on investment as a source of supply and demand. This has been particularly true since 2000. Since then the share of gross capital formation in GDP rose from 35 percent—not an exceptional level for a fast-growing east Asian economy—to almost 50 percent, which is far higher than during the periods of fast growth of Japan and South Korea (see figure 3). This extraordinarily high rate of investment has implications for both demand and supply.

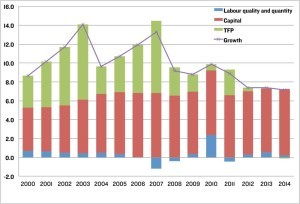

With regard to supply, analysis by the U.S.-based Conference Board (Total Economy Database) shows that additional capital has been almost the sole source of additional supply potential since 2011. The contribution of the growth of “total factor productivity,” which measures the change in output per unit of inputs (and is, accordingly, a measure of innovation), has fallen to nearly zero. The contribution from labor supply (both quantity and quality) has also been negligible (see figure 4). Inevitably, with the investment rate rising and the rate of economic growth falling, returns on investment have declined on average and, without doubt, far more rapidly still at the margin, almost certainly to negative levels. The “incremental capital output ratio,” a measure of the additional output generated by a given level of investment, has risen from about 3.5 in the late 1990s to close to seven in recent years. Thus, investment’s ability to generate additional GDP has halved over this period.

With regard to supply, analysis by the U.S.-based Conference Board (Total Economy Database) shows that additional capital has been almost the sole source of additional supply potential since 2011. The contribution of the growth of “total factor productivity,” which measures the change in output per unit of inputs (and is, accordingly, a measure of innovation), has fallen to nearly zero. The contribution from labor supply (both quantity and quality) has also been negligible (see figure 4). Inevitably, with the investment rate rising and the rate of economic growth falling, returns on investment have declined on average and, without doubt, far more rapidly still at the margin, almost certainly to negative levels. The “incremental capital output ratio,” a measure of the additional output generated by a given level of investment, has risen from about 3.5 in the late 1990s to close to seven in recent years. Thus, investment’s ability to generate additional GDP has halved over this period.

Daniel Gros of the Brussels-based Centre for European Policy Studies has shown that China’s average capital-to-output ratio is higher than that of the far-richer United States. It is almost as high as that of Japan and likely soon to surpass even the latter’s levels. If China’s capital-output ratio is merely to stabilize at current levels, and the economy is to grow at, say, 6 percent, the investment share in GDP needs to fall by about 10 percentage points, to around 35 per cent of GDP. That is where it was during much of the 1990s. It would also still be high by international standards.Gros explains:

Daniel Gros of the Brussels-based Centre for European Policy Studies has shown that China’s average capital-to-output ratio is higher than that of the far-richer United States. It is almost as high as that of Japan and likely soon to surpass even the latter’s levels. If China’s capital-output ratio is merely to stabilize at current levels, and the economy is to grow at, say, 6 percent, the investment share in GDP needs to fall by about 10 percentage points, to around 35 per cent of GDP. That is where it was during much of the 1990s. It would also still be high by international standards.Gros explains:[H]igher investment rates cannot lead to permanently higher growth rates, just a higher output level. The “acceleration” of growth from higher investment cannot be permanent because once the investment rate reaches a certain level, returns will start to fall and growth will return to its underlying rate. An over-investment cycle . . . arises if the temporary nature of the growth boost from a shock to investment is not recognised. This seems to have been the case in China after 2008.

The proposition here—that a decine of 3-4 percentage points in the rate of economic growth could produce a fall of as much as 10 percentage points in the share of investment in GDP—is known as the “accelerator.” The accelerator is then connected to GDP on the demand side, via the “multiplier,” this being the impact of a change in spending (in this case, on investment) on aggregate demand. The interaction between the accelerator and the multiplier makes GDP vulnerable to large downward shocks in demand once decision-makers decide that the lower growth sharply reduces the profitability of planned investment.

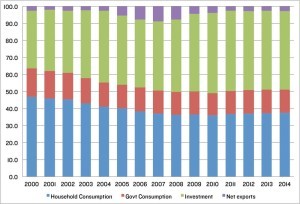

The vulnerability to such a shock to demand has hugely increased over the past 15 years simply because investment has increased so much. Back in 2000, household consumption generated 47 percent of aggregate demand, government consumption 17 percent of demand and investment 34 percent of demand. Net exports also contributed just over 2 percent of demand. By 2007, household consumption had shrunk to a mere 37 percent of demand, government consumption had shrunk to 14 percent of demand, investment had risen to 41 percent of demand and net exports had jumped to an enormous 9 percent of demand. China’s economy had become extraordinarily dependent on both very high investment and very high external surpluses (see figure 5). Then the global financial crisis hit, threatening China’s ability to sustain its huge external surpluses without a slump in domestic output. How did the authorities respond? They promoted an even bigger investment boom, much of it in real estate (see also figure 2). This offset the decline in net exports and maintained economic growth at close to 10 percent between 2009 and 2011, despite the global crisis.In brief, the rise in the investment share in GDP of the past 15 years, and particularly since 2008, is unsustainable. It must ultimately turn into a period when investment grows more slowly than GDP, possibly much more slowly. And given the very high capital-output ratio, it might even shrink.This unsustainably high investment rate is very far from the end of the story. It is only an element of it. Two other significant and ultimately unsustainable disequilibria are associated with the investment boom. One is the suppression of household incomes via still-low wages and low interest rates on bank deposits. Michael Pettis, professor of finance at the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University in Beijing, has argued persuasively that only ever-rising implicit taxation of households has made the extraordinarily high spending on increasingly low-return investments feasible.5According to the World Bank, the share of household disposable income in GDP bottomed out at 59 percent of GDP in 2011. This number looks plausible: Since the share of private consumption in GDP is 40 percent, it would mean that households save a third of their income (see figure 5). The World Bank data also seem consistent with Conference Board data that the share of labor compensation in GDP was 40 percent in 2014, down from 51 percent in 2000 and even a little below 42 percent in 2008.Given the very low shares of consumption, wages, and household disposable incomes in GDP, private consumption can lead growth if and only if a combination of two things happens: First, households radically reduce their savings rate; or, second, income that now accrues as corporate-retained profits or as government revenue is transferred to private households. But the former is quite unlikely in an environment of high policy uncertainty, such as exists today. Meanwhile, the latter would threaten both the incentive to invest and the ability to fund such investments. In any case, the adjustment remains small. The share of household disposable income in GDP was still only 61 percent in 2013.The second disequilibrium closely associated with the investment boom is soaring indebtedness. This has become particularly significant since the global financial crisis, which led to the decision by China’s policymakers to expand credit in order to support a huge surge in investment. “Total social financing” (a broad credit measure) duly jumped from 120 percent of GDP in 2008 to 208 percent in the third quarter of 2015.6 According to the McKinsey Global Institute, gross debt in China jumped from 157 percent of GDP in the last quarter of 2007 to 227 percent in the last quarter of 2012 and 290 percent in the second quarter of 2015. In contrast, gross U.S. debt was only 270 percent of GDP in the last quarter of 2014.7Many imagine that the principal danger created by this rise in indebtedness is that of an unmanageable financial crisis. This is mistaken. In China, an unmanageable crisis is still quite unlikely: It is not only a creditor nation; its government is solvent, it owns and controls the main banks, it is able to regulate private capital outflows, and it offers domestic residents relatively few financial alternatives to bank deposits. The true risks created by the debt overhang are two-fold.The first risk is that leverage works in both directions. During a boom, borrowers obtain higher returns than they expected. During the subsequent bust, both they and the lenders obtain lower returns than they hoped and duly reduce their risk-taking. This happens even if there are not waves of bankruptcies. But if bankruptcies are feared, people will become very unwilling to take risks, because they do not know how large the ultimate losses will be and where they will fall. One might describe this condition as one of pervasive distress. It should be added to the accelerator and multiplier as a powerful mechanism for weakening the economy. As professor Pettis stresses, conventional economics does not pay sufficient attention to such balance-sheet effects.The second risk concerns the sustainability of investment. To sustain growing investment, borrowing must rise. But as economic growth and returns on investment fall, this must look increasingly unwise to both spenders and lenders. Thus, even without any financial crisis, caution about further increasing indebtedness would guarantee a sharp economic slowdown. The dilemma, then, is that the policymakers must want both to prevent and to promote a further build-up of debt.The International Monetary Fund argues that, “Without reforms, growth would gradually fall to around 5 percent with steeply increasing debt.” Yet even with reforms, history suggests that it is extremely hard to move off of an unsustainable path smoothly. One can think about this relatively precisely. The main element to focus upon is the national savings rate.Assume that the level of investment needed to support growth at 6-7 percent a year is 35 percent of GDP. This level of investment is, as past Chinese experience suggests, probably consistent with a roughly stable level of indebtedness: that is, it does not require an explosive increase in debt in support of unprofitable investment. Assume, too, that one wishes to avoid a current account surplus. Then the national savings rate also needs to fall to 35 percent of GDP. For that to happen, public and private consumption must rise to 65 percent of GDP. Assume public consumption were to rise from 10 to 15 percent of GDP and private consumption from 40 to 50 percent of GDP. Assume, too, that households continue to save 30 percent of disposable income. Then household disposable incomes would need to rise by 10 percent of GDP, from 60 to 70 percent. This would slightly more than reverse the decline in the share of household disposable income in GDP over the past 15 years. It would also mean that savings in the rest of the economy—corporate and government—would also roughly halve relative to GDP.At its recent rate, notes professor Pettis, this adjustment could take a quarter of a century. It is almost inconceivable that it could take place, without heroic policy measures, in less than a decade. But this means that investment must continue to be far higher than 35 percent of GDP for a substantial period. That almost certainly mean a continuation of poor-quality investment and soaring excess capacity..The path of reform and successful adjustment, if not blocked altogether, is extremely difficult. This is why, Pettis argues, the only way out is to accept lower rates of economic growth. But this, too, might not work. Once the rate of debt-financed investment starts to fall, the economy risks a severe crisis, as the accelerator-multiplier-distress engines go powerfully into mutually reinforcing operation. Moreover, the continuation of high household savings means sustained increases in indebtedness, as households continue to lend to the rest of the economy.Possible Policy ResponsesThe obstacles to a smooth transition to a different economic structure, given what this means for the distribution of income, the operation of the financial sector and the structure of the economy, are huge. Correspondingly, the ability to avoid a hard landing or, more likely, a sustained period of lower growth than is now officially expected, is arguably far less than many believe. Probably, the best approach would be to continue with reforms while trying to put more spending power into the hands of consumers and investing more in public consumption and environmental improvements. Such a response would be in keeping with China’s needs. It would also require the deliberate and coordinated use of monetary and fiscal mechanisms, in order to sustain demand and shift the distribution of income towards private and public consumption. The magnitudes involved, as noted above, would be large.In practice, however, policymakers are far more likely to try two other, ultimately self-defeating, but immediately simpler alternatives: yet more investment-promoting domestic credit; and a big real depreciation of the renminbi, with a view to creating a bigger trade surplus. Both would be dead ends.Further reliance on the credit engine merely guarantees a bigger slowdown in the end. Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is now far too big to run a sufficiently large current account surplus sustainably. Yet so long as the national savings rate remains not far short of 50 percent of GDP, any substantial decline in investment must lead to a bigger current account surplus. With an apparently reasonable investment rate of, say, 35 percent of GDP, continuation of such a high rate of saving would imply an annual current account surplus (and so net capital exports) of 15 percent of China’s GDP. This would be $1.5 trillion, 15 times the capital of the vaunted Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Even Xi Jinping’s “one belt, one road” investment program could not absorb such a huge surplus of investible funds.Moreover, a steep decline in the external value of the currency could just be the product of letting the currency adjust to market forces. The decline in investment opportunities, capital flight, and the desire of highly indebted companies to repay their foreign debts are already combining to create strong downward pressure. China’s huge foreign currency reserves fell by close to 20 percent between mid-2014 and the end of 2015. Yet, if the currency were allowed to depreciate and the external surplus were to soar, the rest of the world could not run the corresponding current account deficits sustainably. The latter would almost certainly create a protectionist backlash, huge financial crises, or, more probably, both. The only way out is for the government to borrow and spend the surplus savings itself or accelerate the transfer of income to Chinese households. The best way to do the former would be to raise spending on public consumption, including a huge environmental cleanup. The best way to do the latter would be to tax corporations and subsidize consumption.A discontinuity in China’s economic growth is now far more likely than it has been for decades. Moreover, such a discontinuity might not be brief. The challenge facing policymakers is, after all, huge. They need to re-engineer a highly unbalanced and slowing economy without letting it crash. Many analysts, suspicious of Chinese statistics, think the situation is already far worse than official sources suggest, with growth running at closer to 4 percent than 6 percent.8 If so, the investment rate is even more radically unsustainable than now appears to be the case.Chinese policymakers have a stellar reputation for the quality of economic management. But the same was also true of Japanese policymakers three decades ago. There is no doubt that Chinese officials allowed the economy to move onto a radically unbalanced and ultimately unsustainable path after 2000 and especially after 2007. For policymakers to manage a transition to a pattern of growth that is not investment- and debt-led, without losing their way at least for a while, would be an extraordinary achievement.It is also important to consider the political implications. A big question is how the reforms and adjustments now required fit with the concentration of political power in China. Some believe the latter is a necessary condition for the former: only a strong leadership can overcome the obstacles to reform. But a leadership committed to Communist Party supremacy and the concentration of power in its hands might prove unable to accept the necessary decentralization of the economy. At the same time, it might not survive a long period of weak growth.It is perfectly possible, perhaps even likely, that China will become a high-income country one day. But the path ahead looks very bumpy. The huge imbalances built up in the past are becoming binding constraints today. Many countries have looked very impressive until they ceased to be—or, to recall once again Herb Stein’s immortal wisdom: “If something can’t go on forever, it won’t.” The next stage for China’s economy is a conundrum. Its resolution will shape the world.1Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (Free Press, 1992).2The main reason for making the adjustment from GDP converted at market exchange rates to GDP at purchasing power parity (or international prices) is that, at market exchange rates, labor-intensive non-traded services tend to be far cheaper in poor countries than in rich ones. The purchasing power parity adjustment is, to give a simple example, based on the assumption that a haircut is a haircut, whether consumed in China or Japan.Raising the relative price of labor-intensive services in poor countries also increases their GDP per head relative to those of rich countries. In fast-growing developing countries, real wages will tend to rise rapidly. This will raise relative prices of the labor-intensive services whose productivity cannot increase rapidly: a haircut tends to take the same amount of time everywhere. Once real wages have converged, the purchasing power parity adjustment will become relatively trivial.3Pritchett and Summers, “Asiaphoria Meets Regression to the Mean,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 201573 (October 2014).4Andong Zhu and Wanhuan Cai, “The Lewis Turning Point in China and its Impacts on the World Economy,” AUGUR Working Paper (February 2012).5Pettis, Avoiding the Fall: China’s Economic Restructuring (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2013).6International Monetary Fund, “People’s Republic of China: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation”, July 7, 2015, and Michael Pettis, “China’s rebalancing timetable,” Michael Pettis’ China’s Financial Markets, November 29, 2015.7These figures come from unpublished data supplied by the McKinsey Global Institute.8See “Asia Pacific Consensus Forecasts,” Consensus Economics, November 9, 2015.

Then the global financial crisis hit, threatening China’s ability to sustain its huge external surpluses without a slump in domestic output. How did the authorities respond? They promoted an even bigger investment boom, much of it in real estate (see also figure 2). This offset the decline in net exports and maintained economic growth at close to 10 percent between 2009 and 2011, despite the global crisis.In brief, the rise in the investment share in GDP of the past 15 years, and particularly since 2008, is unsustainable. It must ultimately turn into a period when investment grows more slowly than GDP, possibly much more slowly. And given the very high capital-output ratio, it might even shrink.This unsustainably high investment rate is very far from the end of the story. It is only an element of it. Two other significant and ultimately unsustainable disequilibria are associated with the investment boom. One is the suppression of household incomes via still-low wages and low interest rates on bank deposits. Michael Pettis, professor of finance at the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University in Beijing, has argued persuasively that only ever-rising implicit taxation of households has made the extraordinarily high spending on increasingly low-return investments feasible.5According to the World Bank, the share of household disposable income in GDP bottomed out at 59 percent of GDP in 2011. This number looks plausible: Since the share of private consumption in GDP is 40 percent, it would mean that households save a third of their income (see figure 5). The World Bank data also seem consistent with Conference Board data that the share of labor compensation in GDP was 40 percent in 2014, down from 51 percent in 2000 and even a little below 42 percent in 2008.Given the very low shares of consumption, wages, and household disposable incomes in GDP, private consumption can lead growth if and only if a combination of two things happens: First, households radically reduce their savings rate; or, second, income that now accrues as corporate-retained profits or as government revenue is transferred to private households. But the former is quite unlikely in an environment of high policy uncertainty, such as exists today. Meanwhile, the latter would threaten both the incentive to invest and the ability to fund such investments. In any case, the adjustment remains small. The share of household disposable income in GDP was still only 61 percent in 2013.The second disequilibrium closely associated with the investment boom is soaring indebtedness. This has become particularly significant since the global financial crisis, which led to the decision by China’s policymakers to expand credit in order to support a huge surge in investment. “Total social financing” (a broad credit measure) duly jumped from 120 percent of GDP in 2008 to 208 percent in the third quarter of 2015.6 According to the McKinsey Global Institute, gross debt in China jumped from 157 percent of GDP in the last quarter of 2007 to 227 percent in the last quarter of 2012 and 290 percent in the second quarter of 2015. In contrast, gross U.S. debt was only 270 percent of GDP in the last quarter of 2014.7Many imagine that the principal danger created by this rise in indebtedness is that of an unmanageable financial crisis. This is mistaken. In China, an unmanageable crisis is still quite unlikely: It is not only a creditor nation; its government is solvent, it owns and controls the main banks, it is able to regulate private capital outflows, and it offers domestic residents relatively few financial alternatives to bank deposits. The true risks created by the debt overhang are two-fold.The first risk is that leverage works in both directions. During a boom, borrowers obtain higher returns than they expected. During the subsequent bust, both they and the lenders obtain lower returns than they hoped and duly reduce their risk-taking. This happens even if there are not waves of bankruptcies. But if bankruptcies are feared, people will become very unwilling to take risks, because they do not know how large the ultimate losses will be and where they will fall. One might describe this condition as one of pervasive distress. It should be added to the accelerator and multiplier as a powerful mechanism for weakening the economy. As professor Pettis stresses, conventional economics does not pay sufficient attention to such balance-sheet effects.The second risk concerns the sustainability of investment. To sustain growing investment, borrowing must rise. But as economic growth and returns on investment fall, this must look increasingly unwise to both spenders and lenders. Thus, even without any financial crisis, caution about further increasing indebtedness would guarantee a sharp economic slowdown. The dilemma, then, is that the policymakers must want both to prevent and to promote a further build-up of debt.The International Monetary Fund argues that, “Without reforms, growth would gradually fall to around 5 percent with steeply increasing debt.” Yet even with reforms, history suggests that it is extremely hard to move off of an unsustainable path smoothly. One can think about this relatively precisely. The main element to focus upon is the national savings rate.Assume that the level of investment needed to support growth at 6-7 percent a year is 35 percent of GDP. This level of investment is, as past Chinese experience suggests, probably consistent with a roughly stable level of indebtedness: that is, it does not require an explosive increase in debt in support of unprofitable investment. Assume, too, that one wishes to avoid a current account surplus. Then the national savings rate also needs to fall to 35 percent of GDP. For that to happen, public and private consumption must rise to 65 percent of GDP. Assume public consumption were to rise from 10 to 15 percent of GDP and private consumption from 40 to 50 percent of GDP. Assume, too, that households continue to save 30 percent of disposable income. Then household disposable incomes would need to rise by 10 percent of GDP, from 60 to 70 percent. This would slightly more than reverse the decline in the share of household disposable income in GDP over the past 15 years. It would also mean that savings in the rest of the economy—corporate and government—would also roughly halve relative to GDP.At its recent rate, notes professor Pettis, this adjustment could take a quarter of a century. It is almost inconceivable that it could take place, without heroic policy measures, in less than a decade. But this means that investment must continue to be far higher than 35 percent of GDP for a substantial period. That almost certainly mean a continuation of poor-quality investment and soaring excess capacity..The path of reform and successful adjustment, if not blocked altogether, is extremely difficult. This is why, Pettis argues, the only way out is to accept lower rates of economic growth. But this, too, might not work. Once the rate of debt-financed investment starts to fall, the economy risks a severe crisis, as the accelerator-multiplier-distress engines go powerfully into mutually reinforcing operation. Moreover, the continuation of high household savings means sustained increases in indebtedness, as households continue to lend to the rest of the economy.Possible Policy ResponsesThe obstacles to a smooth transition to a different economic structure, given what this means for the distribution of income, the operation of the financial sector and the structure of the economy, are huge. Correspondingly, the ability to avoid a hard landing or, more likely, a sustained period of lower growth than is now officially expected, is arguably far less than many believe. Probably, the best approach would be to continue with reforms while trying to put more spending power into the hands of consumers and investing more in public consumption and environmental improvements. Such a response would be in keeping with China’s needs. It would also require the deliberate and coordinated use of monetary and fiscal mechanisms, in order to sustain demand and shift the distribution of income towards private and public consumption. The magnitudes involved, as noted above, would be large.In practice, however, policymakers are far more likely to try two other, ultimately self-defeating, but immediately simpler alternatives: yet more investment-promoting domestic credit; and a big real depreciation of the renminbi, with a view to creating a bigger trade surplus. Both would be dead ends.Further reliance on the credit engine merely guarantees a bigger slowdown in the end. Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is now far too big to run a sufficiently large current account surplus sustainably. Yet so long as the national savings rate remains not far short of 50 percent of GDP, any substantial decline in investment must lead to a bigger current account surplus. With an apparently reasonable investment rate of, say, 35 percent of GDP, continuation of such a high rate of saving would imply an annual current account surplus (and so net capital exports) of 15 percent of China’s GDP. This would be $1.5 trillion, 15 times the capital of the vaunted Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Even Xi Jinping’s “one belt, one road” investment program could not absorb such a huge surplus of investible funds.Moreover, a steep decline in the external value of the currency could just be the product of letting the currency adjust to market forces. The decline in investment opportunities, capital flight, and the desire of highly indebted companies to repay their foreign debts are already combining to create strong downward pressure. China’s huge foreign currency reserves fell by close to 20 percent between mid-2014 and the end of 2015. Yet, if the currency were allowed to depreciate and the external surplus were to soar, the rest of the world could not run the corresponding current account deficits sustainably. The latter would almost certainly create a protectionist backlash, huge financial crises, or, more probably, both. The only way out is for the government to borrow and spend the surplus savings itself or accelerate the transfer of income to Chinese households. The best way to do the former would be to raise spending on public consumption, including a huge environmental cleanup. The best way to do the latter would be to tax corporations and subsidize consumption.A discontinuity in China’s economic growth is now far more likely than it has been for decades. Moreover, such a discontinuity might not be brief. The challenge facing policymakers is, after all, huge. They need to re-engineer a highly unbalanced and slowing economy without letting it crash. Many analysts, suspicious of Chinese statistics, think the situation is already far worse than official sources suggest, with growth running at closer to 4 percent than 6 percent.8 If so, the investment rate is even more radically unsustainable than now appears to be the case.Chinese policymakers have a stellar reputation for the quality of economic management. But the same was also true of Japanese policymakers three decades ago. There is no doubt that Chinese officials allowed the economy to move onto a radically unbalanced and ultimately unsustainable path after 2000 and especially after 2007. For policymakers to manage a transition to a pattern of growth that is not investment- and debt-led, without losing their way at least for a while, would be an extraordinary achievement.It is also important to consider the political implications. A big question is how the reforms and adjustments now required fit with the concentration of political power in China. Some believe the latter is a necessary condition for the former: only a strong leadership can overcome the obstacles to reform. But a leadership committed to Communist Party supremacy and the concentration of power in its hands might prove unable to accept the necessary decentralization of the economy. At the same time, it might not survive a long period of weak growth.It is perfectly possible, perhaps even likely, that China will become a high-income country one day. But the path ahead looks very bumpy. The huge imbalances built up in the past are becoming binding constraints today. Many countries have looked very impressive until they ceased to be—or, to recall once again Herb Stein’s immortal wisdom: “If something can’t go on forever, it won’t.” The next stage for China’s economy is a conundrum. Its resolution will shape the world.1Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (Free Press, 1992).2The main reason for making the adjustment from GDP converted at market exchange rates to GDP at purchasing power parity (or international prices) is that, at market exchange rates, labor-intensive non-traded services tend to be far cheaper in poor countries than in rich ones. The purchasing power parity adjustment is, to give a simple example, based on the assumption that a haircut is a haircut, whether consumed in China or Japan.Raising the relative price of labor-intensive services in poor countries also increases their GDP per head relative to those of rich countries. In fast-growing developing countries, real wages will tend to rise rapidly. This will raise relative prices of the labor-intensive services whose productivity cannot increase rapidly: a haircut tends to take the same amount of time everywhere. Once real wages have converged, the purchasing power parity adjustment will become relatively trivial.3Pritchett and Summers, “Asiaphoria Meets Regression to the Mean,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 201573 (October 2014).4Andong Zhu and Wanhuan Cai, “The Lewis Turning Point in China and its Impacts on the World Economy,” AUGUR Working Paper (February 2012).5Pettis, Avoiding the Fall: China’s Economic Restructuring (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2013).6International Monetary Fund, “People’s Republic of China: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation”, July 7, 2015, and Michael Pettis, “China’s rebalancing timetable,” Michael Pettis’ China’s Financial Markets, November 29, 2015.7These figures come from unpublished data supplied by the McKinsey Global Institute.8See “Asia Pacific Consensus Forecasts,” Consensus Economics, November 9, 2015.

February 7, 2016

Nice Guy, Bad Driver

El Centro, California, is a dusty little agricultural hamlet on the southern edge of the Imperial Valley, not far from the Mexican border In the spring of 1954, acting on a tip that a junior college out there was looking for football players, two high school friends and I drove all the way from East Texas to see about filling its need. Approaching El Centro from the east on U.S. Highway 80, we sailed safely through an intersection with California Route 111 four miles east of town. We didn’t know it at the time—and it wouldn’t have meant anything to us if we had—but a gifted American novelist and his wife had died in a grinding two-car collision at that very intersection some 14 years earlier.