Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 193

May 16, 2017

Democrats Push Left as Midterm Campaigns Approach

If you thought that Donald Trump’s victory would impel the Democrats to de-emphasize identity politics and social liberalism and pivot even modestly toward the center, think again. At the local level, Democratic politicians are under tremendous pressure to double down on the whole menu of positions favored by the party’s increasingly militant progressive wing. Governing magazine reports:

Betsy Hodges is running for re-election as mayor of Minneapolis this year on a fairly progressive record. She’s devoted some $40 million to affordable housing, put an emphasis on care for young children and signed an ordinance mandating that employers provide paid sick leave.

Nonetheless, Hodges faces several serious challengers running to her left. Hodges has opened herself up to progressive criticism due to her shifting positions on a prospective minimum-wage increase and handling of a high-profile police shooting.

“Even though she’s the most progressive mayor in Minnesota, most of her rivals are to the left of her,” says Larry Jacobs, a political scientist at the University of Minnesota. “There’s no doubt there’s a kind of Robespierre moment in the Democratic Party, where if you’re not sufficiently pure, you’re suspect.”

Some of the leftward march seems to be motivated by the sense that Hillary Clinton’s tepid center-leftism was a dud and the conviction that Bernie Sanders or someone like him might have had a better shot against Trump. This analysis may or may not be correct, but it is too one-dimensional. In fact, Bernie Sanders was to Clinton’s right on many cultural issues, including gun control, feminism, immigration, and identity politics. If you want to drive a Berniebro crazy, you could even argue that Sanders is the reason Clinton lost—that she couldn’t compete with his left-wing economic populism, so she moved even deeper into boutique academic/PC liberal territory to compensate, and that this was ultimately what did her in. And yet, the new generation of Democrats seems to be retreating to hard-line liberal positions in all areas, economic and social alike.

If Trump’s approval rating remains stuck in the low 40s—and especially if it ticks downward even further, as seems increasingly plausible—the Democrats are well-positioned for a major comeback in Congress and the statehouses in 2020. But they could easily blow this opportunity, just as they blew the last one, by learning the wrong lessons from the Age of Trump. Of course, the real loser here is not one party or the other, but the country at large, which seems to be locked into a self-reinforcing cycle of minority-party radicalization under presidents of both parties that is annihilating the vital center.

Does America Still Need Keystone?

After all these many years of dithering, Keystone XL finally has the green light from the federal government that it deserved in the first place. It almost seems fitting, then, that this pipeline beguiled by political dithering and delays is now facing yet another bump in the road at the final hour. TransCanada, the company that proposed Keystone in the first place, is apparently now taking another look at the project to make sure it will be used enough to justify its cost. The Globe and Mail reports:

TransCanada Corp. is reassessing whether oil producers in North Dakota and Montana are still interested in shipping crude through its long-delayed Keystone XL pipeline, now that they have other new options to ship their product, including the Dakota Access pipeline.

The Calgary-based company’s announcement this month comes with the Keystone XL still needing approval of its proposed route through Nebraska and with the Dakota Access, which was designed to transport about half of North Dakota’s oil production, expected to be fully operational by June.

What’s changed, then? For one, the Dakota Access pipeline, which stole Keystone’s prestigious title as America’s most contentious pipeline last year, is now helping transport crude from the Dakotas’ Bakken shale formation to refiners along America’s Gulf coast. That project makes Keystone less of a vital artery for American energy interests.

But what about Canada’s part in all of this? Alberta’s oil sands producers were looking forward to the construction of Keystone as it would provide them a route to those aforementioned American refineries, and the Dakota Access pipeline won’t serve them the way it will for U.S. frackers. For those Canadian suppliers, Keystone remains an important potential option for them to get their product to market.

So even if the rationale is diminished, this project is far from dead. And given the dynamism of U.S. shale production over the past decade, we’d be much better served to err on the side of too many pipelines, rather than too few. That’s especially true as America gears up for what could be a banner year of oil output in 2018.

In the meantime, court cases in Nebraska are holding up the routing approval process. We’ll have to wait for those to be resolved before we learn just how necessary Keystone XL really is.

Toward Detente In the South China Sea?

Earlier this month, China scored a diplomatic victory when the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) rolled over on criticizing its activity in the South China Sea by issuing a communique that skirted the issue of Beijing’s island-building and militarization. This week, more signs abound that China is on a roll, as rival claimants beat a hasty path to Beijing to hash out their disagreements bilaterally.

First, via Reuters, comes the news that Vietnam—once one of the most openly confrontational countries toward China—has agreed on a joint communique with Beijing to keep tensions in check on the path toward a long-term solution:

After what China said were “positive” talks on the South China Sea last week between President Xi Jinping and Vietnamese President Tran Dai Quang, the joint statement stressed the need to control differences.

Both countries agreed to “manage and properly control maritime disputes, not take any actions to complicate the situation or expand the dispute, and maintain peace and stability in the South China Sea”, it added.

The document, released by the Chinese Foreign Ministry, said both had a “candid and deep” exchange of views on maritime issues, and agreed to use an existing border talks mechanism to look for a lasting resolution.

Meanwhile, Reuters reported over the weekend that China and the Philippines are beginning bilateral talks on the South China Sea this week. And while officials in Manila are cautioning that the dispute will not be resolved overnight, President Duterte has sounded an upbeat note, even suggesting that a lucrative deal could be in the works to share the sea’s energy resources with China and Vietnam.

None of this means that the thorny South China Sea dispute will come to a swift conclusion, but the talks are significant in their own right. China has always insisted that its maritime disputes be settled on a bilateral basis, contra the Obama administration’s efforts to use ASEAN as a multilateral proxy to challenge Chinese claims. Now, after 8 years of Obama and four months of Trump, many of China’s neighbors have come to a similar conclusion: with the U.S. policy process visibly hobbled, they might as well fend for themselves and cut a deal with Beijing.

Here’s Why Petrostate Oil Cuts Have Disappointed

The global oil market is rebalancing at an accelerating rate, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). For OPEC and the eleven other petrostates that have been cutting their collective production through the first half of this year, that could be seen as a sign that their plan to reduce the oversupply in the market is working. But as the Wall Street Journal reports, a closer look at the IEA’s monthly oil market report describes a more unsettling scene for these major producers:

[The] IEA—a global energy adviser for governments—warned Tuesday that more work may have to be done, implying longer cuts are needed to drain excess inventories. In the run up to the cuts, OPEC pumped so much oil that storage levels rose, delaying the rebalancing.

Even if the OPEC and non-OPEC cuts are extended into the second half of 2017, the IEA said, “stocks at the end of 2017 might not have fallen to the five-year average, suggesting that much work remains to be done in the second half of 2017 to drain them further.”

We noted last October that OPEC was playing a savvy and somewhat disingenuous game ahead of its meeting to moot output cuts: by significantly upping its total production in the latter half of last year, it was making the task of then reducing that production in 2017 a whole lot easier.

At the same time, however, that decision has diluted the effect of these cuts, so it’s perhaps no great surprise that oil prices have had such a tepid rebound, just as it might be expected that these petrostates will need to continue to adhere to this strategy for many more months if they want to erase the oversupply (Russia and Saudi Arabia have already said they’ll be cutting through March of next year).

Meanwhile, the United States continues to take advantage of this ceding of market share as shale producers emerge as the big winners from this petrostate production cut.

Two Unflattering Possibilities on Trump’s Intelligence-Sharing Screw Up

Yesterday afternoon, the Washington Post released a bombshell of a report, detailing how President Trump nonchalantly disclosed highly compartmentalized information to the “Two Sergeys”, Foreign Minister Lavrov and Ambassador Kislyak, during their Oval Office meeting last week. In a nutshell, a swaggering President Trump (“I get great intel, I have people brief me on great intel every day”) reportedly revealed certain details about how the United States obtained widely-discussed intelligence about ISIS’ plans for developing undetectable laptop bombs for detonation on planes.

The public uproar seems to have been anchored on the fact that President Trump shared information with Russia, of all countries. The optics are absolutely terrible, given that the conversation with the Russians happened on the same week Trump fired FBI Director James Comey, who was himself pursuing leads into possible collusion between Trump campaign officials and Russian intelligence in last year’s elections. But ultimately, that’s all they are: bad optics. In the greater scheme of things, this is a red herring. The fact that Trump appeared to recklessly reveal trade secrets to an adversarial power is at the crux of the story, not which adversarial power, per se.

President Trump’s childish bragging to his interlocutors about “great” intel is the other main source of dismay and outrage, and here at least, the Post‘s reporting just feels correct. After over 100 days of this Administration, we have a pretty good sense of our Commander in Chief, and regrettably, this sounds like something he might say. Through scores of interviews over the past few weeks, our President routinely comes off sounding like some kind of Hollywood ingénue, constantly in the process of learning obvious things for the first time. His innocence before his own thundering ignorance is almost endearing—until you realize that this man in some ways has the fate of the world in his hands.

But here, too, we ought to be careful. The Post‘s sourcing is anonymous, and is the retelling of an overheard conversation. The words attributed to Trump betray such abject ignorance of the gravity of the matters he is dealing with that it’s impossible to rule out the possibility that this detail was maliciously leaked. This Administration is riven by so much mistrust and mutual suspicion that anything is possible. Just because it sounds right does not mean we ought to embrace the reporting quite yet.

Lawfare boiled down the question like this: if the President disclosed this information in an impulsive and boastful kind of way, this is catastrophic. No, the President has not broken any laws—he technically can’t reveal classified information by definition; by the very act of revealing it to non-cleared individuals, he is declassifying it. The question is whether he did so consciously or carelessly. To put it in the bluntest terms possible, if the President blindly blundered into this mess, it betrays a level of negligence that will give people good cause to doubt that he is fit for office.

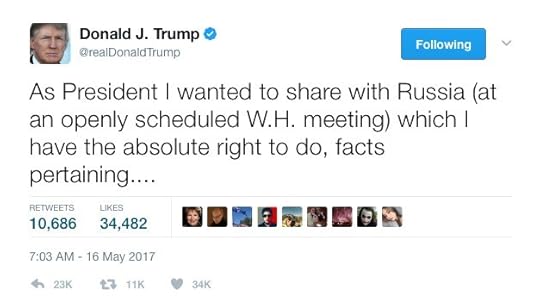

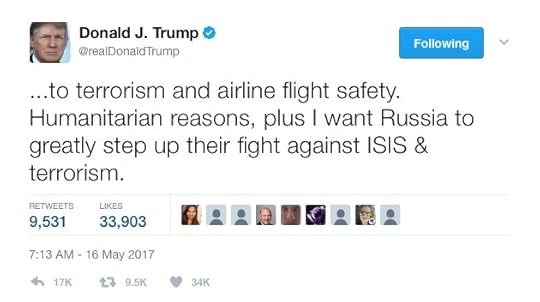

Trump’s team clearly spent the night grappling with this issue, and released a lawyerly pair of tweets this morning, which attempt to put the President firmly on the side of intentionality, rather than carelessness:

As President I wanted to share with Russia (at an openly scheduled W.H. meeting) which I have the absolute right to do, facts pertaining….

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 16, 2017

…to terrorism and airline flight safety. Humanitarian reasons, plus I want Russia to greatly step up their fight against ISIS & terrorism.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 16, 2017

Expect this to be the line of defense going forward. Trump meant to do this. He is in control of himself, and is leading deliberately rather than blindly improvising. The goal was to get the Russians more engaged in the fight against terror.

But is it fully exculpatory? Not at all. As a judgment call, it’s still a very poor one, for reasons that have, once again, very little to do with Russia as such. As the Washington Post said, what was damaging in Trump’s disclosure is that he revealed details—specifically the city controlled by ISIS “where the U.S. intelligence partner detected the threat”—that could let a hostile intelligence service ferret out the source. Trump clearly sees the Russians as potential allies, much more so than any Russia watcher deems prudent, so it clearly didn’t occur to him that the Russians are overwhelmingly likely use the information for their own, narrow, bloody ends. But the death of several informers on the ground and the drying up of a potentially critical source of intelligence in Syria is small beer compared to the real damage wrought.

The damage has to do with the intelligence-sharing relationships we have around the world. Israeli papers were reporting in January that Mossad was already skittish about sharing intelligence with the United States ahead of Trump’s inauguration. Such worries today seem to have been fully warranted. Even if we are to take Trump at his tweets, and grant that he made a conscious decision to share classified details with the Russians in order to make it more likely that they cooperate with him against ISIS, not a single intelligence agency is going to think that the President made a prudent decision here. The world’s spies know Russia and its security services for what they are, and at best they now see Trump as a knave. It’s almost certain that the Israelis will start withholding important information from us, if they hadn’t already. And some serious soul-searching is likely to take place among the “Five Eyes”, as well.

That’s where the debate stands as of this morning: was the President “extremely careless” in the handling of highly compartmentalized intelligence, or did he just make a conscious decision that is almost certain to cost us the goodwill and partnership of our allies around the world? It’s hard to say which one is worse.

The Problem with the “F” Word

A few weeks ago, as I was walking to the university where I teach, I noticed the phrase “Trump = Fascist” graffitied on a wall. I paused a moment, experiencing déjà vu. I had seen the phrase similarly plastered all over my Facebook feed, as well as in the news.

It seems that the “fascist” tag suddenly is back in vogue. All sorts of political commentators hearken back to the 1930s, wondering whether Trump is closer to a Hitler or “just” a Mussolini. Prior to the election, The New Republic warned its readers that “Yes, Donald Trump is a Fascist.” Salon joined in the chorus, publishing a piece informing readers that “Trump’s not Hitler, he’s Mussolini.” Even the New York Times ran a piece in December asking America, “Is Donald Trump a Fascist?” (the answer: “A little”).1 More particularly, academics of a certain ideological coloration across the country have leaned into the word, organizing students at universities from Cal State Long Beach to Harvard to “resist Fascism.” The latter recently established a “Resistance School” to “strengthen the skills they need to take collective action” against Trump.2

There is one problem, however. Few tossing around the word with such alacrity seem to know what it actually means. While that might be excusable for a graffiti artist, most of the rest ought to know better. Some do. Yet most choose silence over objection. The way of thinking that has engulfed the academy over the past few decades has made the field of history, in particular, vulnerable to this sort of hyperbole. And it does not suffer dissenters lightly.

The best way to understand Fascism is to look at the historical record. Four 20th-century regimes self-consciously identified as Fascist: Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’s Spain, and Salazar’s Portugal. These were very different sorts of regimes, a fact that has made a strict definition of the word difficult, and sustained a rich historiographic debate, carried on over the last twenty years by scholars such as Stanley Payne, A.J. Gregor, Robert O. Paxton, and Roger Griffen. But that definitional problem has partially enabled its elastic overuse in recent times; history professor Jeffrey Blutinger not long ago publicly defined Fascism as any right-wing authoritarian movement that “demonizes those who are different.” Such a definition is vague enough to be useless.

All four leaders came to power through violence. For the racialist right in Germany, there were two coup attempts (the Kapp Putsch in 1920 and the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923) prior to Hitler’s chancellorship. Mussolini seized power through his “March on Rome,” which, while semi-legal, was backed by the threat of force by tens of thousands of black-shirted Fascist thugs. Franco came to power after a military coup turned into a bloody civil war. Salazar became Prime Minister for life via a military coup in 1926.

When they achieved power, each did precisely the same thing within months: They banned the political opposition, suspended or reshaped their national constitutions, established concentration camps for political opponents, nationalized or co-opted major national industries, and created massive social welfare programs. Their goal was the fundamental reshaping of national life. As Hitler said in 1937, the goal of his National Socialist Revolution was “To create a single people . . . and within this people to raise a new and higher social community.” This superior society would depend on the fundamental reshaping of its individual members and a rejection of individuality itself. Mussolini wrote in 1932 that, “anti-individualistic, the Fascist conception of life stresses the importance of the State and accepts the individual only in so far as his interests coincide with those of the State.” The greater the penetration of the state into society, the greater its control and the ability to reshape it to the ruling party’s will.

For all his bluster, Trump has done none of these things. His most controversial policy initiatives involve—mostly—enforcing existing immigration laws. Its most contentious element in that regard—the refugee ban—brought cries of outrage and comparisons with German anti-Semitism. Yet despite its fundamentally flawed nature, the differences are plain. Trump’s proposed ban was not directed inward toward American citizens or green card holders, but outward. It would have affected seven Muslim-majority countries (leaving untouched about two dozen others). Only one of the states in question fully controlled its national territory and has a reasonably functional central government. That country is Iran, a state that enforces its own travel ban on Jews and homosexuals. Perhaps that might remind intellectuals of something?

And of course when his Executive Order was struck down by the courts, President Trump accepted the legal decision and tried to revise the Order by dropping Iraq from the list and changing some language—unsuccessfully so far. This highlights another disparity: Despite his belligerent rhetoric, he has (thus far) used only existing tools of Executive Branch power, many of which were crafted during the past two post-9/11 administrations, to govern.

More generally, his appointments at the Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, and the EPA indicate a desire to dismantle much of the administrative state. Whatever one thinks of Trump’s program, his “philosophy” of government seems to point toward a smaller and less intrusive central government, which is the opposite of the Fascist ideal.3

All of this begs the question: Why do so many keep referring to this Administration as Fascist when its actions seem contrary to the very idea of Fascism? I would argue the origin of the word’s overuse and misuse lies in the greatest challenge to American postmodernism: the question of the Holocaust.

Since the linguistic turn—the philosophical reversal of the relationship between language and “fact” which underlies much of modern relativism—the humanities have increasingly shied away from any universal claims. The first to go were moral claims, such as the idea of evil and the language of sin, virtue, and truth. Later, the very idea of a “fact” became viewed as anachronistic. But, in the words of historian Berel Lang, the “moral enormity” of the Holocaust means that it is a “test case for historical representation.”

Denying the Holocaust is, rightly, the greatest sin a modern historian can commit, even in an era where the very concept of “facts” is challenged. But by drawing that line in the sand, intellectuals have been forced to acknowledge a fundamental flaw in their own postmodern reasoning: The Holocaust happened, and its denial is a crime against truth itself. But how can that be, when history is merely the product of hegemonic narratives?

Simultaneously, the postmodern conception of evil remains challenged by the existence of Nazi Germany. Two American academics, Cynthia McSwain and Orion White, once said of evil in the present age “that it is impossible and even dangerous to define it with any finitude.” But anyone looking at the Holocaust and Third Reich recognizes that it cannot be understood without its moral and ethical implications. Fundamentally, the Holocaust was evil.

In serving as the fundamental crux of this postmodern paradox, the perpetrators of the Holocaust have taken on new meaning. With relativism’s attitude to both “evil” and “fact,” debating any issue of practical consequence has become difficult. As a result, “Fascism” has become a catchall for whatever postmodernists oppose. It has become the only safe reference to evil or wrong that many postmodern scholars are willing to credit. Unwilling to seek a more nuanced analogy, and thus expand their moral universes beyond that of the Holocaust, postmodern intellectuals are forced to rely on a singular, hopelessly expansive word to describe all they detest. For them, “Fascist” is the only word that has any moral force. They in turn are echoed by other commentators, from journalists to graffiti artists.

This new postmodern consensus is one factor, among many, that has radicalized American political rhetoric. It represents an emotional reaction more than it does a rational argument. It impedes the sort of reasoned disagreement that leads to mutual understanding, and has alienated large segments of the general public. But to use the word “Fascist” accurately would destroy its utility as an evasion of postmodern illogic. In a way, the misuse of the “F” word reflects a moral crisis of its own, one perhaps as worrying as President Trump’s election.

1Jeffrey Herf came to a similar conclusion much earlier in an effort to debunk the fascist label: “Is Donald Trump a Fascist?” TAI Online, March 7, 2016.

2Masuma Ahuja, “Harvard Students Launch Course on Resisting ‘The Trump Agenda,’” CNN Online, April 3, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/04/03/us/harvard-resistance-school/ .

3A point made months ago by David Brooks: “The Internal Invasion,” New York Times, January 20, 2017.

The Kuril Islands on the Installment Plan

In the last twelve months, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin found enough time to have three face-to-face meetings with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, not counting the many encounters on the sidelines of various international fora and other senior-level meetings. The leaders last met again in Moscow two weeks ago. At the meeting’s conclusion, they agreed to continue their dialogue and to meet again at least two more times by the end of the year.

Such an ambitious pace for summits should raise some eyebrows. With Russia still beset by sanctions and quasi-isolated on the world stage, these meetings represents something of an aberration. And at least in public, Abe and Putin have a much warmer rapport than Putin shares with any of the other G7 leaders.

For Putin, these regular meetings with his Japanese colleague have both symbolic and practical benefits.

Symbolically, Abe’s friendship shows that Russia is not completely shunned by all the countries in what can very broadly be described as the “Western” camp. Domestically, the warm relationship between the two leaders is shown to be sowing discord among Western allies, if not yet fatally splitting them. And who knows what the future brings? After all, if an influential country in the so-called “Western” alliance communicates with the Kremlin, others may consider joining the conversation soon, too, at some point.

More pragmatically, with the Kremlin’s post-Crimea “pivot to the East” strategy currently heavily reliant on cooperation with China, Putin is looking to diversify his options in the region should relations with Beijing take a wrong turn. And thus far, his gambit appears to be paying off. Moscow has for the better part of a decade tried to entice Japan into investing in Russia. Apart from the joint project of developing the LNG terminal at Sakhalin-II, all those enticements have yielded almost nothing.

Last December’s meeting between Putin and Abe, in the Japanese Prime Minister’s hometown of Nagato, represented a sea change. Japanese companies all of a sudden became willing to invest in a country with shrinking consumer demand and slim chances for realizing meaningful growth. Mitsui Group, admittedly a Japanese pioneer in the Russian market, announced the purchase of a 10 percent stake in Russia’s R-Pharm, for a staggering $200m, while Sojitz Corporation, supported by the Japanese state-backed investment fund, expressed interest in modernizing and running the regional airport in Khabarovsk, a city of some 600,000 in Russia’s Far East, adjаcent to the Chinеse border. Additionally a group of renowned Japanese architects and urbanists, supported by a team of Japanese investors, announced plans to transform the provincial town of Voronezh, 320 miles to the south of Moscow, into a pleasant, modern, walkable city.

Abe’s goal remains negotiating a final territorial settlement with Russia over the Kuril Islands—a real sore spot for Tokyo. Back in 2010, when then-President Dmitry Medvedev traveled to the Kurils, the Japanese denounced the stunt as an “unprecedented insult”; two years later, they described Medvedev’s return visit as “a cold shower”. In his third term, Putin has signaled the possibility for an opening.

Russia’s official media insisted that Putin had made no concessions during the Nagato negotiations. However, leading up to the summit, the Russian President dropped some hints as to how a deal might possibly emerge. In a September interview with Bloomberg, Putin said that Russia does not trade in territories. However, he went on to refer to a hard-won “compromise” with Beijing where a “part of the territory [some disputed islands on the Amur river —ed] was permanently assigned to Russia and part of the territory permanently assigned to the People’s Republic of China”. It’s important to remember that most Russians see that episode as a territorial concession to its powerful neighbor; Putin’s elegant wording made it sound much more equitable. Later, in a December interview to Nippon TV and The Yomiuri Shimbun, Putin reiterated his willingness to seek a solution to the peace treaty problem on the basis of the 1956 Declaration, which envisaged the transfer of two of the four Kuril Islands to Japan.

While it’s impossible to know for sure what is really going on, we appear to be witnessing an intricate staged spectacle—a simulated struggle between the two countries over their respective national interests, when in truth the dispute over the Kurils appears to have already been settled. The newfound willingness of the Japanese to invest in comparatively stagnant Russia is a powerful tell.

The key to understanding the dynamic is the looming reelection of Vladimir Putin to the Russian Presidency in 2018. No final deal will be announced before Putin wins his fourth term, because the repercussions of its announcement are an unnecessary variable in a carefully stage-managed re-anointment. On the other hand, the kabuki theater on display this year only helps the Russian President look good: the larger the Japanese investments in the Russian economy, the more visible are Putin’s accomplishments in settling a lingering dispute with an important neighbor.

But rest assured that the marketing for the deal will commence as soon as polling stations close on March 18 of next year. If the elections produce the expected outcome, the Kremlin’s pundits and policy wonks will readily explain to the Russians why remote rocks far in a cold sea should be abandoned to Japan.

Spain Joins the Mo’ Money Caucus

Spain thinks the Eurozone would work better if it spent… more money on Spain. Politico reports:

Spain’s conservative Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has joined the ranks of those who are demanding a deep overhaul of the eurozone.

Madrid has submitted to the European Commission a proposal for deeper economic integration of the 19 countries using the euro, the economy ministry confirmed Monday. It calls for completing the banking union and implementing euro bonds, an anti-crisis budget, and a common unemployment insurance scheme. […]

A summary of Spain’s proposal by its economy ministry argued that the architecture of the eurozone has proven vulnerable to economic shocks and that the lack of absorbing mechanisms has resulted in “high unemployment rates in the countries most affected by the crisis.”

“It’s clear that we need to improve the governance of the eurozone,” the country’s foreign minister, Alfonso Dastis, told POLITICO last week. “The banking union will be the key test.”

Spain here seems to be aligning itself with Emmanuel Macron, who has already headed to Berlin for preliminary talks on Eurozone reforms. Berlin’s response to his reform agenda has so far been cool, but this suggests that pressure on Germany will grow after its elections, as the Spanish right wing joins the French center left and Italy in a clear call for Eurozone reforms that will tilt the system more in favor of its indebted southern members.

There is good reason to sympathize with all the parties in this—and to be skeptical of them all too. The Spaniards are right that the Eurozone in its current form does not work, and they are also right that a functioning currency union would have some of the features the Spaniards are proposing. But it would also have to include a more thorough reform that would address many if not all of Germany’s concerns.

The big problem now is that it appears that neither side, so far, is able to meet the minimum conditions of the other. Germany seems as unable as it is unwilling to make the concessions Spain and its allies want. And the Latin countries so far have not come close to the minimum reforms that the Germans insist must be the price. It is a slow-moving game of chicken, with the ECB working to stave off a real crisis using the limited but necessary tools in its toolbox.

Diesel’s Dirty Secret

Diesel was, for a time, considered by some to be a greener alternative to unleaded gasoline. Those days seem numbered, as the environmental case against the fuel is starting to look stronger. As the AP reports, new research suggests that diesel’s pollution is being grossly underestimated all over the world:

The work published Monday in the journal Nature was a follow-up to the testing that uncovered the Volkswagen diesel emissions cheating scandal. Researchers compared the amount of key pollutants coming out of diesel tailpipes on the road in 10 countries and the European Union to the results of government lab tests for nitrogen oxides.

They calculated that 5 million more tons (4.6 metric tons) was being spewed than the lab-based 9. 4 million tons (8.5 million metric tons). Governments routinely test new vehicles to make sure they meet pollution limits.

Experts and the researchers don’t accuse car and truck makers of cheating, but say testing is not simulating real-world conditions.

Europe has a long history of gaming its car emissions tests, and it’s a history we’ve been following for some time. Testers get creative to juice extra mileage out of vehicles, employing such novel techniques as removing side-view mirrors to reduce drag, taping up doors, and removing “extras” like stereos to make vehicles lighter.

This lax testing has made diesel to seem more environmentally friendly than it actually is. Diesel’s green case was dubious to begin with, though: the fuel emits more local air pollutants than gasoline, and has been blamed for the recent rise in toxic smog in many of Europe’s biggest cities. Europe saw this as an acceptable trade-off, however, because diesel is capable of getting higher mileage.

But it seems as if those local pollutants being spewed out of the tailpipes of diesel-powered cars and trucks are a bigger problem than previously believed. So much for Europe’s “green” credibility.

May 15, 2017

North Korea Tests Missile (And Moon)

Well, that didn’t take long: five days after the inauguration of a pro-engagement president in Seoul, North Korea successfully launched a ballistic missile, defiantly vowing afterwards that such tests would continue at “any time and place” that Pyongyang’s leadership deemed fit. What’s worse, the Norks’ latest test appears to mark a meaningful milestone in Pyongyang’s march toward an inter-continental ballistic missile, as analyst John Schilling explains over at 38 North:

North Korea’s latest successful missile test represents a level of performance never before seen from a North Korean missile. The missile would have flown a distant of some 4500 kilometers if launched on a maximum trajectory. It appears to have not only demonstrated an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) that might enable them to reliably strike the US base at Guam, but more importantly, may represent a substantial advance to developing an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

Apart from its threat to the United States, North Korea’s latest provocation poses a clear test of Moon Jae-in. South Korea’s president was elected amid pledges to de-escalate tensions with the North and reconsider the deployment of the THAAD missile defense system, and he wasted no time beginning talks with Beijing on those issues last week. But Pyongyang’s latest test could complicate Moon’s nascent efforts at diplomacy, reminding an already skeptical public that promises of good-faith negotiations are no guarantee of responsible behavior from the North.

Indeed, the test is likely to harden a political reality that Moon is already confronting: he has neither the numbers in the National Assembly nor a popular mandate to make controversial moves on North Korea, like reversing THAAD or reinstating the cancelled Kaesong Industrial Zone project. :

“Moon will first have to tackle issues which have some kind of common ground among political parties and the public, not divisive issues such as THAAD,” said Kim Jun-seok, a political science professor at Dongguk University. […]

“Unless Moon is out of his mind, he shouldn’t continue to drag on with the THAAD issue. He really can’t oppose it anymore,” said Hong Moon-jong, a member of the conservative Liberty Korea Party, the second-largest party with 107 seats, behind the 120 seats held by the ruling party.

Two other major opposition parties, the centrist People’s Party and the conservative Bareun Party that together have 60 seats, also support the deployment.

In this fraught climate, Moon may tread lightly before granting significant concessions to Beijing or launching direct talks with Pyongyang. And indeed, his initial reaction to Sunday’s missile test suggest that may be the case. In sternly denouncing the test, Moon pointedly stated that “dialogue is possible only when North Korea changes its behavior.”

If that truly is Moon’s standard, then it’s quite likely there won’t be much of a change forthcoming.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers