Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 160

July 11, 2017

China Denies Responsibility For North Korea

China has made its strongest statement yet suggesting it won’t play ball with American efforts to pressure North Korea. Reuters:

Asked about calls from the United States, Japan and others for China to put more pressure on North Korea, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said it was not China ratcheting up tension and the key to a resolution did not lie with Beijing.

“Recently, certain people, talking about the Korean peninsula nuclear issue, have been exaggerating and giving prominence to the so-called ‘China responsibility theory,'” Geng told a daily news briefing. […]

“I think this either shows lack of a full, correct knowledge of the issue, or there are ulterior motives for it, trying to shift responsibility,” he added.

China has been making unremitting efforts and has played a constructive role, but all parties have to meet each other half way, Geng said.

“Asking others to do work, but doing nothing themselves is not OK,” he added. “Being stabbed in the back is really not OK.”

It is no secret who Geng is addressing here: the so-called “China responsibility theory” has been the consistent centerpiece of Donald Trump’s thinking on North Korea. The President’s approach has evolved tactically over time—with an initially solicitous approach toward China turning lately into a screws-tightening campaign—but all along, it has been animated by the belief that China holds the unique leverage that can “solve” the North Korean crisis once and for all.

The Chinese have rejected that thinking before, and it would seem that Trump’s recent imposition of secondary sanctions has not changed their mind. Beijing seems to be holding out hope that Trump will come around to their preferred formula: the removal of the THAAD missile defense system and the suspension of U.S.-South Korean military exercises, in exchange for Pyongyang halting nuclear tests and coming to the negotiating table.

But the Trump administration is unlikely to agree to those terms: if anything, it is only growing bolder in its pressuring of China and its muscular demonstrations of the THAAD system. Today, the U.S. announced that it had successfully shot down an intermediate-range ballistic missile in a first-of-its-kind test:

The test was the first-ever of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system against an incoming IRBM, which experts say is a faster and more difficult target to hit than shorter-range missiles. […]

“The successful demonstration of THAAD against an IRBM-range missile threat bolsters the country’s defensive capability against developing missile threats in North Korea and other countries,” the Missile Defense Agency said in a statement.

China is not going to like that message. And with Beijing and Washington remaining at loggerheads over who is to blame for North Korea—let alone how to handle the crisis—we are likely in for some tense and turbulent times in the U.S.-China relationship.

The post China Denies Responsibility For North Korea appeared first on The American Interest.

Germany Has a Coal Problem

A new study out of Brussels offers up a conclusion that will surprise precisely no one: coal power is Europe’s biggest pollution problem. But here’s something that might turn a few heads: green-crazed Germany is among the continent’s worst offenders on this front. The AP reports:

The European Environment Agency said in a report late Sunday that half of the plants responsible for the largest releases of air and water pollution were in Britain, with a total of 14. Germany was second with seven, followed by France and Poland, each with five.

A quarter of the plants the EU agency identified as being the worst polluters in Europe can be found in Germany. How could this be? After all, Berlin is quick to point out the fact that it’s sourcing roughly a third of its energy from renewable sources these days, the result of heavy subsidies afforded to wind and solar power producers (that have also led to some of the EU’s highest electricity prices).

That surge in renewables is part of the German energiewende, but it isn’t the only component of that energy transition. Berlin is also phasing out its nuclear power fleet, a decision hastened by the 2011 Fukushima disaster. Of course, a rational examination of the prospect of nuclear power in Germany would show that the country faces none of the numerous risks of natural disaster that threaten Japan’s own reactors, but then, environmentalists aren’t the first group one turns to for rational reflection.

Nuclear power is, like renewables, a zero-emissions energy source, but unlike wind and solar, it can be relied on for consistent supply. Its absence has put Germany in a bind, and has led to a greater reliance on coal-fired power plants even as Berlin crafts its image as a green leader. Nice work if you can get it.

The post Germany Has a Coal Problem appeared first on The American Interest.

Reading the News in Tehran

On June 11 the Wall Street Journal ran an —the Persian-language news service of Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty (RFE-RL), one of five U.S. government-supported networks that provide news and information to foreign audiences around the world.1 The author of the piece, Sohrab Ahmari, listed a dozen news items that, in his view, reveal “dysfunction” at Radio Farda.

Five items on Ahmari’s list are reports on events in Israel that contain inaccuracies suggestive of a pro-Palestinian bias. Another five characterize American critics of President Obama’s nuclear arms agreement with a Persian word that could be translated as “extremist.” And the last two items cover routine activities of President Hassan Rhouhani and his deputy in a manner that Ahmari finds unduly deferential.

This sounds pretty bad, until we step back and consider that these 12 stories appeared over a five-year period, from 2012 to 2017, during which Farda produced approximately 18,400 news reports about events in Iran and the region. Assuming that all 12 news items on Ahmari’s list are in fact biased or inaccurate, that is still less than a tenth of one percent of the total. Ahmari declined my request for an interview, so I cannot say how he obtained these 12 items. In his article he makes no claim to have sifted through five years of Farda reporting, but neither does he indicate a source. What I can report, based on interviews with RFE-RL management, is that Farda responded to his sole inquiry with a lengthy memo addressing each item, inviting him to visit RFE-RL’s Prague headquarters, and defending the work of its journalists, more than twenty of whom have in recent years been threatened and harassed—as have their families back in Iran.

Apparently Mr. Ahmari didn’t get the memo. His article makes no mention of the Iranian regime’s many hostile measures against Farda, which include not only threats and harassment directed at journalists but also costly efforts to block the service’s radio, television, and online communications. In fact, Tehran spends more money to block Farda’s programming than Farda spends to produce it.

In spite of these hostile measures, millions of Iranians use Internet proxies to access Farda. In May of this year, Farda’s website attracted 28 million page views and received over 60,000 comments, and ten million people listened to its radio programs online. These Iranians are not turning to Farda for anti-Israel rhetoric, defenses of President Obama’s nuclear arms agreement, or flattery of their rulers. They can get all that on their state-run media—without risking arrest.

As a grantee of Congress, RFE-RL is required to undergo two external reviews every year. Because Farda is the language service that receives the most criticism (from Washington as well as Tehran), RFE-RL’s management ordered an additional review this spring. The person hired to conduct the review was an experienced Western journalist fluent in Persian, who compared Farda with the other international channels penetrating Iran and concluded that, of the lot, Farda was the least biased and most independent.

Farda is not without problems. A major issue cited in every external review is the lack of reporting from inside Iran. The reason for this is simple: anyone caught reporting for Farda, or even posting a message on its website, Facebook page, or other social media, is immediately sent to prison. As noted in the memo sent to Ahmari, the official newspaper of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei routinely calls Farda “CIA official radio.”

There was a time, not too long ago, when digital media were perceived as having the potential to liberate Iran. When the “green movement” filled the streets of Iran’s cities with protests against the rigging of the 2009 election, Western pundits dubbed it “the Twitter revolution.” But the name didn’t stick, because the movement was swiftly crushed by a combination of old-fashioned brutality and new-fangled digital repression. Today the battle continues between tech-savvy Iranians and a security state increasingly skilled at using online tools to censor, surveil, and propagandize its people.

This brings us to a second problem, one that existed before the digital age. Ahmari gets one thing right: the key mission of Farda (and of the 25 other language services at RFE-RL, as well as its four sister networks) is to provide high-quality local and regional news to audiences in countries where information is tightly controlled by a repressive regime hostile to the United States. This “surrogate news” mission involves many challenges. One of the most daunting is to teach émigrés from those same countries how to temper their oppositional passion for the sake of dispassionate reporting.

It is easy to overlook how crucial émigrés are to the whole undertaking of surrogate news. Identifying important stories in a closed society, verifying the facts, adjusting the nuances for a particular audience, then delivering the story in fluent, idiomatic language via the most effective media platforms—these are not things that Americans can do alone. They require the cooperation of émigrés. But—here’s the challenge—émigrés tend to come with baggage.

During the Cold War, when RFE-RL provided surrogate news to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, its dozen or so language services employed a motley assortment of characters: exiled leaders and bureaucrats, including a few former Communists; poets and pamphleteers adrift in Paris and London; native speakers raised in the West; and countless activists, all loyal to different political factions, who quarreled heatedly over who should take power once their countries were liberated.

These Cold War émigrés had the requisite linguistic and cultural savvy, but very few arrived at RFE-RL knowing how to practice good journalism. Driven by a passionate desire to end the scourge of Communism, most had grown up being hammered by Soviet propaganda (not to mention Nazi propaganda during the war). So their initial impulse was to hammer right back. It took hard work and patience to teach them the difference between propaganda and journalism.

Part of the lesson was that internecine quarrels within a given language service must not be allowed to impinge on its news operations. Once learned, this lesson stuck, because most of the men and women who became committed journalists at RFE-RL understood in their gut how easy it would be for a hostile government to exploit their particular quarrels.

But here’s a question that came up in my interviews with Farda management: What happens when you combine 21st-century digital media with overheated émigré politics? You get a third, very real problem that does not yet have a solution.

Generally speaking, RFE-RL reporters regard digital media as a blessing because along with its sister networks RFE-RL has become quite adept at using digital tools to move information into and out of closed societies. Indeed, these networks are in some ways more adept than their commercial cousins because their priority is news, not profit. But unfortunately, this is not the whole story. To seasoned staff trying to teach good journalism to raw recruits, digital media can also be a curse.

Here in America, it is evident that Facebook, Twitter, and other social media blur the line between disciplined reporting and undisciplined ranting. For many young reporters (and some old ones), professional journalism, with its strict standards of veracity and objectivity, is just a day job. The real action, the stuff that stirs the blood, is on social media—especially personal accounts not monitored by employers. In that space, the best way to build trend-lines and clicks is to steer every discussion into an ever narrower, nastier gutter.

This two-tier practice is worrisome enough in the context of an open society. It is far more worrisome in the context of surrogate news, because instead of cooling the political passions of émigrés, online indulgence ignites them. In the past, RFE-RL employees understood the danger of letting hostile governments fan the flames of their internecine quarrels. Today that understanding is in danger of being lost, as all of us, not just the enemies of freedom but also its supposed friends, seek advantage in fanning our own flames.

1Voice of America (VOA), started in 1942; Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB), started in 1983; Radio Free Asia (RFA), started in 1996; and Middle East Broadcasting Networks (MBN), started in 2002.

The post Reading the News in Tehran appeared first on The American Interest.

Another City Eyes Chapter Nine

Even as the stock market booms, many American cities are watching their financial situations deteriorate as they struggle to cover explosive pension obligations for retired civil servants. Chicago is in dire straits, with analysts weighing the possibility of bankruptcy for the public school system. Meanwhile, in Hartford, Connecticut—another major city in a wealthy blue state—there are also rumblings of Chapter Nine. Bloomberg reports:

Like many other local governments across the country, Hartford — city of Mark Twain and the young John Pierpont Morgan — has been grappling with budget problems for years. On the same day that Illinois lawmakers finally scraped together a long-overdue budget, Hartford hired the law firm Greenberg Traurig LLP to evaluate its options, which include bankruptcy. It would be the first prominent U.S. municipality to seek protection from its creditors since Detroit did so in 2013.

As the article notes, Connecticut is in trouble in part because the hedge fund industry, one of its major sources of economic activity, has contracted in recent years, cutting into the state’s tax revenue even as it has to pay growing pension bills. This is a higher-end version of the problem that forced Detroit into bankruptcy: As the manufacturing industry faded, the Motor City could no longer afford defined-benefit pensions that depended on a constantly growing economic base. Both cities would have been better off with 401(k)-style pension plans, whereby workers saved for their own retirement and the city wasn’t stuck paying a guaranteed income to thousands of retirees even as its economic base shrank. Defined-benefit pensions made sense when we expected companies and industries to stick around for long periods of time; but at a time of economic transition, they can bankrupt local governments in the blink of an eye.

More broadly, Hartford’s struggles highlight the severity of the crisis of public finance for states and localities across the United States. The fact that states like California, Illinois and Connecticut—home to dynamic economies and enormous reserves of wealth—are struggling mightily to fund their pension obligations even in the midst of a long bull market suggests that there are major structural problems below the surface. They are likely to be exposed in the next recession.

The post Another City Eyes Chapter Nine appeared first on The American Interest.

July 10, 2017

The Wages of the Campus Revolts

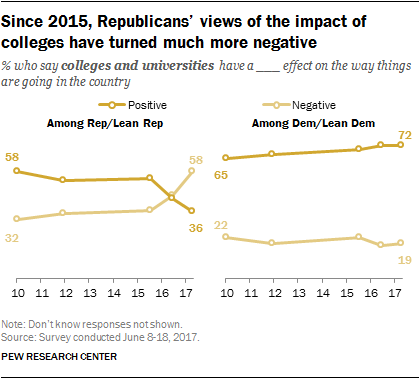

Colleges have been perceived as liberal bastions for decades, but the latest round of campus culture warring—beginning around 2014 and continuing through the present day—has had a sudden and dramatic impact on conservatives’ perceptions of the Ivory Tower. According to a new Pew survey, Republicans saw colleges and universities as having a “positive effect on the way things are going in the country” by about a 20 point margin until 2015. In the last two years, however, GOP esteem of America’s higher education institutions started to collapse. Today, Republican 58 percent of Republican voters say colleges have a negative effect on American society, compared to just 36 percent who say they have a positive effect.

The reason for the collapse is clear: Over the past few years, leftwing activism on college campuses has reached a level of intensity not seen since at least the “canon wars” of the late 1980s and early 1990s, and possibly not since the countercultural movements of the 1960s. Meanwhile, campus PC blowups—over trigger warnings, safe spaces, sexual harassment, and offensive speakers—dovetailed with the 2016 presidential campaign, as Hillary Clinton touted “intersectionality” on her Twitter feed and Donald Trump reveled in raising a middle finger to the ever-proliferating codes of academic liberalism.

Conservative media has also played an important role. Privileged students ensconced in $60,000-per-year institutions shouting down speakers for incorrect opinions on gender pronouns makes the perfect foil for the new anti-PC right. So right-wing journalists have followed the excesses of the campus left closely, spreading news of the latest insanity far and wide, often with a touch of hyperbole thrown in.

Most campus lefties will probably look at these numbers as evidence that Republicans are even more anti-intellectual than they thought, and that the #resistance against them needs to be taken up a few notches. This would be a big mistake. The homogenization of leftwing views on college campuses, and the obvious hostility to conservative ones was bound to produce a backlash from conservative voters. That backlash has been wrapped up in class conflict between a highly-credentialed professional class and a working class that finds higher education and the well-paying jobs it provides to the elite increasingly out of reach.

Meanwhile, Republicans control an overwhelming share of America’s statehouses, and so have unprecedented power to defund and restructure public higher education. And Congressional Republicans could restrict the flow of student loans that academia depends on or subject massive university endowments to ordinary tax rates (most are currently exempt). In other words, America’s higher education system, as currently structured, depends on consensus support from both parties. If universities continue to torch their reputation with the right, they may find that some of the privileges and resources and social prestige they have become accustomed to will go up in flames as well.

The post The Wages of the Campus Revolts appeared first on The American Interest.

India, Japan, and U.S. Put on a Show for China

The United States, India, and Japan are kicking off the Malabar naval exercises today, in the largest version to date of the annual drills that have put China on edge. Reuters:

Military officials say the drills involving the U.S. carrier USS Nimitz, India’s lone carrier Vikramaditya and Japan’s biggest warship, the helicopter carrier Izumo, are aimed at helping to maintain a balance of power in the Asia-Pacific against the rising weight of China. […]

The Indian navy said the exercises would focus on aircraft carrier operations and ways to hunt submarines.

The navy has spotted more than a dozen Chinese military vessels including submarines in the Indian Ocean over the past two months, media reported days ahead of Malabar.

The Malabar drills are not officially directed at any particular country, but in recent years they have increasingly annoyed the Chinese. In 2015, Japan became a permanent member of the exercises, sparking anxiety in Beijing about a U.S.-India-Japan axis. And this year, the message to China is none too subtle: by focusing on tracking submarines, the parties are clearly signaling their displeasure with the expanding network of Chinese subs in the Indian Ocean. It is also no coincidence that the U.S. cleared a deal to sell surveillance drones to India last month, just weeks ahead of the Malabar drills. With a combination of surveillance equipment and naval cooperation, the U.S. is helping India keep a watchful eye on China’s maritime activities.

Meanwhile, the Chinese are keeping a close watch on the Malabar exercises themselves: according to First Post, Beijing has deployed a surveillance ship to the Indian Ocean to snoop on the drills. With the Indian and Japanese navies cooperating more closely at the encouragement of the U.S., China may finally be starting to feel some more forceful and coordinated pushback against its maritime moves.

The post India, Japan, and U.S. Put on a Show for China appeared first on The American Interest.

India, Japan and U.S. Put On A Show For China

The United States, India, and Japan are kicking off the Malabar naval exercises today, in the largest version to date of the annual drills that have put China on edge. Reuters:

Military officials say the drills involving the U.S. carrier USS Nimitz, India’s lone carrier Vikramaditya and Japan’s biggest warship, the helicopter carrier Izumo, are aimed at helping to maintain a balance of power in the Asia-Pacific against the rising weight of China. […]

The Indian navy said the exercises would focus on aircraft carrier operations and ways to hunt submarines.

The navy has spotted more than a dozen Chinese military vessels including submarines in the Indian Ocean over the past two months, media reported days ahead of Malabar.

The Malabar drills are not officially directed at any particular country, but in recent years they have increasingly annoyed the Chinese. In 2015, Japan became a permanent member of the exercises, sparking anxiety in Beijing about a U.S.-India-Japan axis. And this year, the message to China is none too subtle: by focusing on tracking submarines, the parties are clearly signaling their displeasure with the expanding network of Chinese subs in the Indian Ocean. It is also no coincidence that the U.S. cleared a deal to sell surveillance drones to India last month, just weeks ahead of the Malabar drills. With a combination of surveillance equipment and naval cooperation, the U.S. is helping India keep a watchful eye on China’s maritime activities.

Meanwhile, the Chinese are keeping a close watch on the Malabar exercises themselves: according to First Post, Beijing has deployed a surveillance ship to the Indian Ocean to snoop on the drills. With the Indian and Japanese navies cooperating more closely at the encouragement of the U.S., China may finally be starting to feel some more forceful and coordinated pushback against its maritime moves.

The post India, Japan and U.S. Put On A Show For China appeared first on The American Interest.

Georgia’s Dilemma

While the nadir in post-Soviet Russo-Georgian relations passed with the defeat of the United National Movement by the Georgian Dream coalition in the 2012 parliamentary elections, the subsequent Georgian governments have nevertheless maintained the country’s goal of NATO and EU membership. Over the past few years, however, both polling data and anecdotal evidence suggest a possible shift of Georgian sympathies away from the European and Euro-Atlantic vector toward Russia, including an increase in support for Georgian membership in Putin’s Eurasian Union. Assessing the different geopolitical orientations of the South Caucasus countries, one of my Georgian friends ruefully concluded that “the Armenians proved to be smarter”—surely one of the most wrenching admissions any Georgian could ever make.

Is this renewed Georgian interest in partnering with Russia simply a flash in the pan caused by frustration with the halting, drawn-out process of trying to join NATO and the EU? Or have the Georgians erred fundamentally with their wager on the West? Even as the level of Georgian support for NATO and EU membership remains high, is a reassessment of Georgia’s civilizational trajectory perhaps underway? Could the Georgians behave like the Armenians, orienting their country toward Moscow and accepting Russian bases in exchange for security assistance and subsidized energy?

The complexity of Georgian attitudes toward their mighty northern neighbor defies any simple categorization into pro- or anti-Russian. It has been thus for centuries, and remained so with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Georgia’s brief medieval ascendance as a Christian power with mostly Muslim neighbors came to an abrupt and catastrophic close with the Mongol conquest of 1236. For over five centuries thereafter, the Georgian lands were mostly divided, either among foreign conquerors or feuding Georgian principalities. For most of this time Georgian monarchs were vassals of Muslim empires, principally the Ilkhans, Persians, and Ottomans. Georgian rulers operated on a short leash when their suzerains were at the apogee of their power, and secured greater leeway as their overlords experienced dynastic decline. This ebb and flow in Georgia’s political fortunes was punctuated by occasional invasions, such as the serial devastations of the country by Tamerlane in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. The Georgians also endured periods of intense raiding by warlike tribes from the North Caucasus. The cumulative effect was the constriction of the Georgian living space through the extirpation of the Georgian population in some regions, and the conversion of Georgians to Islam and their assimilation with their conquerors.

The expansion of Orthodox Christian Russia into the North Caucasus in the 18th century thus appeared as a godsend to the Georgians, and the rulers of Kartli and Kakheti (eastern Georgia) began to explore transferring their allegiance from Persia and becoming a Russian protectorate. Sporadic efforts culminated in the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk, which established Kartli and Kakheti as a Russian protectorate with Russian confirmation of its internal sovereignty and territorial integrity under the continued rule of the Bagratid Dynasty. As if to underscore the new ambivalence of his loyalties, King Irakli II of Kartli and Kakheti began striking copper coins with the two-headed Russian eagle while continuing to mint silver coinage along traditional Islamic lines.

Irakli’s dalliance with Russia led to a devastating Persian invasion in 1795. To the Georgians’ dismay, no help was forthcoming from the Russian protector. In the aftermath of the Persian depredations, the Russian Empire formally annexed Kartli and Kakheti in 1801, and seized most of the remaining Georgian lands from the Ottoman Empire by 1829.

In many respects, Russian rule was a boon to the Georgians in the 19th century. Their lands were safe from their erstwhile Muslim overlords, and with the Russian conquest of the North Caucasus, the destructive raiding from that quarter likewise ceased. Tbilisi became Russia’s administrative capital in the South Caucasus, and the city recovered from the destruction wrought by the Persians. Consonant with the usual Russian imperial practice, Georgian nobles were welcome to assume positions in the Russian military and bureaucracy. Both the economy and the population expanded apace.

At the same time, however, Russia alienated its Georgian subjects by abolishing the two institutions that had consolidated and preserved the Georgian nation through centuries of foreign conquest—the monarchy, with its venerable Bagratid Dynasty, and the autocephalous Georgian Orthodox Patriarchate. These two moves, never consummated by any of Georgia’s numerous Muslim conquerors, cemented Georgia’s role not as a client state or even a vassal, but as an integral part of the Russian Empire. They seemingly precluded the tried-and-true practice of quietly leveraging and expanding whatever autonomy the Georgians had managed to salvage from their latest conqueror.

The revolutions of 1917 and the collapse of Russian rule in the South Caucasus ushered in a short, tumultuous period of British and German occupation, brief independence under a Georgian national government, and ultimately Bolshevik conquest in early 1921. As the Russian Empire had not been organized territorially along national lines, there was no general agreement on borders among the peoples of the South Caucasus. The Georgians therefore found themselves in conflict during this period with the neighboring Armenians and Azeris, as well as with smaller nationalities like the Abkhaz and the Ossetians, none of whom shared the Georgians’ understanding of which lands constituted “Georgia.”

During the Soviet period, the Georgian intelligentsia and party structures came in for their share of purges, and advocacy for Georgian independence was severely punished. However, the Georgians as a whole did not endure national traumas along the lines of the Ukrainian and Kazakh famines of the 1930s or the mass deportations of Balts, Crimean Tatars, and various North Caucasus peoples. Their architectural patrimony was not subjected to the level of destruction of Russia’s own. The fact that Stalin was himself from Georgia might have spared the country the worst of his repressions. Tbilisi was considered open, relaxed, and prosperous by Soviet standards, and late-Soviet jokes invariably depicted Georgians as wealthy, with the source of their money identified as, or presumed to be, some sort of shady business practice. The major eruption of Georgian national sentiment prior to perestroika came, ironically, in 1956 as a reaction to Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization policy. Georgian demonstrators were dispersed by Soviet troops, with the number of dead estimated as several dozen to several hundred.

This unhappy incident was reprised in 1989, as the Soviet Union was starting to unravel and Georgians again began agitating for greater leeway, even independence. On April 9 Soviet troops cleared demonstrators from Rustaveli Boulevard in central Tbilisi by attacking them with batons and spades, leaving 20 demonstrators dead. The perceived brutality of the incident not only inflamed Georgian nationalist sentiments, it also poisoned Georgian public opinion against the authorities in Moscow and paved the way for the ascent to power of the fiery nationalist Zviad Gamsakhurdia, elected as Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia on November 14, 1990.

Gamsakhurdia’s “Georgia for the Georgians” approach alarmed the country’s numerous ethnic minorities and stoked separatism among the Abkhaz and Ossetians. At the same time, his anti-Russian rhetoric irked Moscow and motivated Russian Communists and nationalists to support the separatists. Finally, Gamsakhurdia’s inept governance plunged the country as a whole into anarchy and civil war, paving the way for his own ouster in early 1992 and the triumph of Russian-abetted separatism in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Eduard Shevardnadze, who benefited from a little Russian facilitation in emerging as Gamsakhurdia’s successor, took a very different tack, eschewing anti-Russian rhetoric, bringing Georgia into the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and accepting Russian military basing in Georgia. It is scarcely remembered today, but when the First Chechen War broke out in 1994, the only country that unequivocally supported Moscow was Georgia. After all, Chechens had fought on the side of the Abkhaz, and the subsequent war in Chechnya seemed to demonstrate the wisdom of a common Russo-Georgian front against separatism. The implied tradeoff, at least in Georgian minds, was that Georgia would be Russia’s best friend in exchange for help restoring Georgia’s territorial integrity.

And for a couple of years in the mid-1990s, there was a palpable ambiguity in Moscow’s attitude toward the separatist regimes in Georgia. However, notwithstanding Shevardnadze’s conciliatory efforts, there remained a powerful current of Russian support for the separatists. This support was justified intellectually by the assessment that Georgia’s separatist entities are totally beholden to Moscow in a way that Georgia proper could never be. Georgia would always have the ability to build relationships with other centers of power. The separatists had no such option, and therefore represented Moscow’s best bet in the South Caucasus.

Quite apart from any dispassionate assessment of whether Russia’s interests would be better served by supporting Georgia or the separatists, Shevardnadze personally labored under the burden of Russian hatred for his supposed role, as Gorbachev’s foreign minister, in the collapse of the Soviet Union. Thus, even as he tried to make Georgia Russia’s best friend, Shevardnadze constantly had to watch his back. He survived several assassination attempts, most notably one in which Igor Giorgadze, whom Moscow had imposed on Shevardnadze as his security chief, was implicated. After the attempt Giorgadze fled to Moscow, which rebuffed extradition requests by claiming that the Russian authorities did not know his whereabouts—a circumstance that didn’t prevent him from providing multiple interviews to Russian journalists.

By the end of Shevardnadze’s rule the bankruptcy of his “best friend of Russia” policy was evident. During the Second Chechen War, Chechen separatists were able to establish a foothold in Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge. Rather than training and equipping the Georgians to clean them out, Russia proposed to send in its own forces. With the Russian peacekeeping operations in Abkhazia and South Ossetia already taking on the character of a foreign occupation, the Georgians understandably declined, turning instead to the Americans for a train-and-equip program. Moscow was irritated but had only itself to blame if the imperative to weaken Georgia had become an even higher Russian priority than ridding the Pankisi Gorge of Chechen fighters. As his wager on friendship with Moscow showed no sign of paying off, Shevardnadze increasingly sought to court NATO.

Moscow’s reaction to the fall of Shevardnadze and the ascent of Mikheil Saakashvili was rich in irony. Russian national chauvinists, who had cursed and undermined Shevarnadze for a decade, suddenly raised a howl of protest that their Eduard Amvrosiyevich had been toppled by an American stooge. Moscow’s undisguised support for separatism in Georgia was highlighted by the negative Russian reaction when Saakashvili quickly reestablished central-government control over the Ajara region, deposing a Russian-backed local warlord, Aslan Abashidze. Moscow, the implacable foe of separatism in the North Caucasus, was taking a completely different approach on the south side of the mountain range.

Indeed, any lingering Russian ambiguity about supporting Georgia’s separatists had vanished very soon after Putin came to power. Moscow abandoned any pretense about facilitating the return of Georgian refugees to Abkhazia, blaming all impediments on Tbilisi rather than the separatists. The negotiating fora for resolving the separatist conflicts were occasions for Russia to berate and pressure Georgia rather than to seek a formula for restoring Georgia’s territorial integrity. Moscow openly seconded Russian officials to the separatist administrations, began mass issuance of Russian passports to the inhabitants of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and menacingly proclaimed Moscow’s intention to defend these newly minted “Russian citizens.”

It is important to bear in mind that these Russian actions antedated Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. It was Russian antipathy and meddling that generated Georgia’s turn toward the West, not vice versa. I have sometimes mused that Russia’s governing elites must have met in secret conclave in the early 1990s and decided that Moscow’s top priority in the South Caucasus would be to drive Georgia and the West unwillingly into each other’s arms. Certainly Russian policy was so successful at alienating Georgians that one could be forgiven for supposing that a Euro-Atlantic vocation for Georgia was the Kremlin’s actual intent.

However, Georgia’s civilizational reorientation, myopically abetted by Moscow, has run up against a natural barrier. The Balts, with their deep historical and cultural ties to Germany, Poland, and Scandinavia, were welcomed into Euro-Atlantic institutions as long-lost family. Not so Georgia. If Westerners found Georgia a fascinating and even beguiling place, it was due to its exoticism, not its familiarity. Georgia’s historical and cultural influences were Byzantium, Persia, the Arabs, the Turks, and latterly Russia—not Europe. If Westerners didn’t instantly recognize Georgia as a long-lost patch of their traditional patrimony, that’s only because it wasn’t. This is not a deal-breaker for Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration, but it is definitely an obstacle.

Georgia has long been part of the Russian information space, which has had an effect on Georgian perceptions. Among the Russian concepts most influential on Georgian security thinking has been the conviction that the West bears unremitting hostility toward Russia. Given this shared Russo-Georgian perception, how could Georgians not expect the West to come substantively to their aid in any confrontation with Moscow? Given the presuppositions, NATO’s failure to admit Georgia and blanket the country with American bases ought to come as a surprise to Russians; it certainly has perplexed the Georgians. Indeed, it has taken Georgians a while to grasp the fact of the West’s fundamental ambivalence toward their country.

The question is not whether granting MAP status to Georgia at the 2008 Bucharest Summit would have forestalled the subsequent Russian invasion—it clearly would not have done so. Rather, the issue is whether the Alliance is willing to do anything substantive short of full Article 5 guarantees to protect the security of prospective members. For Georgia, the answer in the years prior to the 2008 war was an unambiguous “no.” That answer was loud enough to be clearly audible in the innermost recesses of the Kremlin.

Moscow apparently figured out the lay of the land before Tbilisi did. A string of Russian provocations beginning with the 2007 missile incident at Tsitelubani raised barely a ripple of protest from the West. Each Russian move, seemingly inconsequential in isolation, cumulatively amounted to a creeping Russian annexation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The West constantly admonished Tbilisi not to overreact to Russian provocations, but never saw fit to urge Moscow to stop them.

I hope my Georgian friends can forgive me for saying so, but I do not particularly romanticize about a Georgia oriented toward the West at the cost of permanent enmity with Russia. No, my vision is even more utopian than Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration. I dream of a Russia that appreciates Georgia’s uniqueness and respects Georgian sovereignty enough to serve as a worthy partner, rather than a compulsory overlord, for Tbilisi. Unfortunately, however, in the post-Soviet order, Moscow has taken on the historical role of the Persians, Ottomans, and North Caucasus tribes in dismembering Georgia and eliminating the Georgian population from various areas. Under the present circumstances, Russo-Georgian reconciliation would require Tbilisi to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and abandon any hope of returning Georgian refugees to those regions. Moreover, there would be no guarantee even then that Moscow would not resume its divide et impera approach to Georgia, perhaps fanning the embers of separatism in Ajara; awarding Javakheti to the Armenians, Russia’s “loyal millet”; or even anointing local warlords to serve as Moscow’s proconsuls in other parts of Georgia.

For better or worse, since 1991 Moscow has made a strategic choice in the Caucasus to favor those groups who have no option but abject dependence on Russia, rather than to court people like the Georgians who could be persuaded to cooperate with Russia, but who have—and would like to maintain—wider options. The Armenians have not been smarter so much as simply trapped. If their gamble on Russia—their only real option in any event—has been paying dividends so far, the Armenians should pocket them while they can. If Kremlin policies should lead to another systemic collapse of Russia like in 1917 and 1991, Armenia—and even more so Russia’s separatist clients—will fall fast and hard. Disorder on its northern border would not be pleasant for Georgia either, but at least Tbilisi would be able to restore the country’s territorial integrity. Russia is great and powerful; Georgia is small and inconsequential. Still, the day might come when the Russians could sorely benefit from Georgian friendship, and perhaps come to regret their shortsighted wager on separatism.

Georgia finds itself facing a dilemma. The West respects Georgian sovereignty and is willing to provide modest assistance and encouragement, but does not view the country as a natural fit in the Euro-Atlantic family, and is in any event thoroughly absorbed by other, more compelling problems. By contrast, Russia cares deeply about Georgia. Alas, this Russian attention is Georgia’s misfortune unless Moscow reverses its policy of favoring a weak, divided, and ultimately subordinate Georgia. Hence, neither a wager on the West nor on Russia offers any short-term solution to the pressing problem of the country’s sundered territorial integrity and consequent constriction in Georgian living space.

Georgians with a historical perspective will recognize the parallels with periods in their country’s past, when Georgia had to maneuver uneasily among mightier powers and seek whatever advantage wherever it might be found. Unfortunately, the sense of déjà vu is scant consolation for the current generation of Georgia’s elites, faced with guiding their country through the latest tribulation in its long and turbulent history.

The post Georgia’s Dilemma appeared first on The American Interest.

Germany’s Trade Surplus: ‘Not Good!’

The Economist’s cover story this week, on the danger’s of Germany’s trade surplus to the world, is a must read. Chancellor Angela Merkel, host of last week’s G20 Summit, has carefully cultivated a role for her government as chief foil to the supposedly anti-free-trade crusader President Trump. In response to his calls to protectionism, government ministers in Berlin have relished the chance to portray themselves as standard-bearers for that old neoliberal creed—that free movement of capital and goods has and will continue to produce economic miracles if we all just keep the faith.

But, as the Economist points out, there is the nagging issue of Germany’s persistent trade imbalance, which reached nearly $300bn last year. Their leader points to the origins of this economic phenomenon:

Underlying Germany’s surplus is a decades-old accord between business and unions in favour of wage restraint to keep export industries competitive (see article). Such moderation served Germany’s export-led economy well through its postwar recovery and beyond. It is an instinct that helps explain Germany’s transformation since the late 1990s from Europe’s sick man to today’s muscle-bound champion.

The writers go on to note the dire consequences of this policy, advantageous as it might be for Germany:

But the adverse side-effects of the model are increasingly evident. It has left the German economy and global trade perilously unbalanced. Pay restraint means less domestic spending and fewer imports. Consumer spending has dropped to just 54% of GDP, compared with 69% in America and 65% in Britain. Exporters do not invest their windfall profits at home…

For a large economy at full employment to run a current-account surplus in excess of 8% of GDP puts unreasonable strain on the global trading system. To offset such surpluses and sustain enough aggregate demand to keep people in work, the rest of the world must borrow and spend with equal abandon. In some countries, notably Italy, Greece and Spain, persistent deficits eventually led to crises. Their subsequent shift towards surplus came at a heavy cost. The enduring savings glut in northern Europe has made the adjustment needlessly painful. In the high-inflation 1970s and 1980s Germany’s penchant for high saving was a stabilising force. Now it is a drag on global growth and a target for protectionists such as Mr Trump.

Our readers, of course, ought not be surprised that we agree with this assessment: our own WRM has pointed to the merits of some of the criticism leveled at Germany’s trade policy, as well as to the implications of the status quo for the world economy.

This is an important issue, and we urge our readers to pore over the Economist‘s offering, which, in that magazine’s best trademark style, is both approachable and substantive. Especially on this issue, all too frequently signal has been drowned out by the rhetorical noise of simplistic black-and-white narratives. Do read the whole thing.

The post Germany’s Trade Surplus: ‘Not Good!’ appeared first on The American Interest.

Show Me the Money!

Empty financial promises lie at the very core of the Paris Accords—a promise of $100 billion per year, paid indefinitely into the future by the developed world to developing countries as the price of their participation. Obama promised this, knowing full well that the U.S. Congress would never go along with the U.S. share of this total—$30 billion or so, per year, as far as the eye can see.

And now that the U.S. is pulling out, Turkey—and a lot of other developing countries—realize that without the U.S. financial commitment, they could come up short. They now want the other advanced countries that are staying in the deal to make up for what the U.S. won’t be paying.

Newsflash: that won’t be happening. France is groaning under debt. Germans hate shelling out money, and the EU doesn’t know how it will make up for the losses due to Brexit, much less how it will pony up tens of billions for a green extortion fund.

The FT has some choice details:

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, surprised the German hosts of the G20 summit on Saturday when he told reporters his country may be less inclined to ratify the Paris agreement in the wake of the US decision, suggesting it could jeopardise funds promised to developing countries.His comments came just hours after he approved a final communiqué at the meeting in Hamburg where the US was left isolated after 19 of the group’s 20 members pledged to fully implement an “irreversible” Paris agreement.

Germany’s environment minister, Barbara Hendricks, downplayed Mr Erdogan’s remarks on Sunday saying: “It’s about access to international financial mechanisms”, rather than a fundamental rejection of the Paris accord.

That the Germans (and presumably other bien pensant Europeans) were reportedly “surprised” couldn’t be more surprising. This was perhaps the most predictable outcome imaginable.

The fact is, the money was never going to come—especially as a lot of it would be going to corrupt and dictatorial governments. Money to Burma even as the army shoots Rohyingya? To Zimbabwe as Mugabe and his clan line their pockets? Brazil, where the entire political class either has been or is about to be indicted for corruption? Venezuela? Cuba? North Korea? Syria?

The reality of the Paris has always been that they are a set of non-binding commitments to emissions goals in return for non-binding promises to pay lots and lots of money at some later date. It all works as long as everyone agrees to believe in fairies and unicorns. All that the United States has done by walking away early is to expose the whole arrangement for the farce that it is.

And this is just the beginning. Erdogan isn’t going to be the only leader in the developing world who wants the cash up front.

The post Show Me the Money! appeared first on The American Interest.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers