Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 14

January 30, 2020

Beyond Parties of One

In Germany, center-right Christian Democrats and center-left Social Democrats are in trouble. In the neighboring Czech Republic, the country’s mainstream parties “find themselves in an advanced state of decay,” says Karel Schwarzenberg, the former Foreign Minister, ex-presidential candidate, and friend of Václav Havel. Enter billionaire populist Andrej Babiš. It is happening across the West, this loosening of voter ties to traditional parties, these vacuums being filled.

Lawmakers who “owe just about everything to him [are] perfect foot soldiers” for a leader with “an expansive notion of power.” He has “almost unchecked authority … building a fawning cult of personality.” No, this is not a description of a Trump second term. That’s the New York Times on French President Emanuel Macron, a “liberal authoritarian,” as Etienne Soula of the German Marshall Fund puts it.

Something structural is afoot.

Back in 2015, the American Enterprise Institute’s Gary J. Schmitt—now a TAI contributing editor—had a bead on Donald J. Trump: His policies were “substantively an inch deep and bombastically a mile wide. . . his flippant comments, vulgar attacks on opponents, and appeals to the public’s anger and fears … demagogic.” But, writing in the Weekly Standard at the time, Schmitt also identified something arguably more important. Wrote Schmitt:

At some level, candidates should reflect the party’s principles. Or, at least, that was the original intent for creating modern political parties. Otherwise, voting would be a matter of choosing this or that personality on a ballot who might or might not be anchored to some broader substantive program. […] It is a rather remarkable thing that a political party has so little say over who its nominee is. . . . Political parties should not have to follow their putative leader, lemming-like, off the proverbial cliff.

Prescient. Babiš and Macron created their own parties of One. We will see about the shape of a post-Merkel Germany. In the United States, the Republican Party has become the party of Trump.

Irish political scientist Peter Mair was arguing before his death in 2011 that the decline of political parties was leading to a hollowing out of representative democracy. To revive and sustain themselves, contended Mair, political parties would need to act both responsibly and responsively. As we know by now, a glaring lack of the latter has led to populism galore. “Do you think Americans care about Ukraine?” quipped recently the American Secretary of State.

The abdication of elites has gotten us into the current bind, and now a paradox. We trust neither experts nor government. Yet we need expertise and a managerial class to lead us out of our mess. We also need stable, healthy political parties to re-anchor our democracy. Unless, of course, you believe Mr. Trump, in his “great and unmatched wisdom,” has it all covered. Today’s “Forgotten Man” may see Trump as his advocate. But the President also happens to be a reckless fabricator, avid conspiracy theorist, and self-adoring narcissist who seeks to consolidate power by manipulating a pliant, subservient following. None of this can be good for fixing democracy. Or for tackling the nation’s problems.

None of this is to absolve the left. Multiculturalism and identity politics bear responsibility for American malaise. Part of the blame for the new populism lies with those who pushed a large policy agenda well ahead of any democratic consensus among the American electorate. We see more trouble ahead in the neo-Marxism, woolly-headed internationalism, and run-away political correctness of progressives.

TAI remains determined to look for the bigger picture, working chiefly to help rebuild a broad political and intellectual center. We want relevant, gritty detail, but without the inane food fights. Through convening and publishing, we will do our best to create a platform for gifted writers and thinkers—both seasoned and early-career—to tackle the problems our readers care most about.

In the current print issue, arriving in mid-February, Tyler Cowen explains his optimism for liberalism, democracy, and capitalism. This, while Elisabeth Braw finds evidence—in history and language—of eroding democratic culture. Karina Orlova sees in the movie Joker warnings of how social media are changing protest and participation. Her take might surprise you. In reviewing The War on Normal People, Philip A. Wallach appreciates Andrew Yang’s sincerity and lack of pretension—even as he finds the presidential candidate’s case for universal basic income wanting.

Still, two cheers for anything that steers us away from Trumpism—and to a politics and public policy both responsive and responsible.

The post Beyond Parties of One appeared first on The American Interest.

The New, Rotten Normal

Unmaking the Presidency: Donald Trump’s War on the World’s Most Powerful Office

Susan Hennessey and Benjamin Wittes

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020, 432 pp., $28.00

Whatever happens with impeachment, if the Democrats do not make a hash of the elections, in less than a year Donald Trump will depart from the White House for good. Can things snap back to normal? Will Trump’s presidency be seen as an unfortunate aberration, or will the chaos, the lying, and the depravity continue? No question is more important for the future of American democracy. One place to look for answers is in the nature of the presidency itself. Has Trump’s unique brand of politics altered the institution in irreversible ways?

A new book, Unmaking the Presidency by Benjamin Wittes and Susan Hennessey, is an excellent starting point for any such inquiry. Wittes is the author of several previous well-received books about American government and a founder of the indispensable Lawfare blog (where I have been an occasional contributor). Hennessey, a top editor at Lawfare and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, is a former National Security Agency attorney. In their book they place Trump in historical context and examine the changes he has wrought.

They note at the outset that the American presidency has never been a static institution. Over the course of two-plus centuries, it has evolved along several dimensions, including its size and organization and its relationship with the other branches of government as well as the public. With a rich history behind it, Trump came into office seemingly bound by a dense web of traditions and expectations about what a presidency should look like. The most striking thing about him, in Wittes and Hennessey’s view, is how thoroughly he has cast aside those traditions and expectations and created a truly novel conception of the office:

Trump proposes a presidency that elevates the expressive and personal dimensions of the office above everything else. It is one in which the institutional office and the personality of its occupant are almost entirely merged—merged in their interests, in their impulses, in their finances, and in their public character.

With this basic observation as their launching pad, Wittes and Hennessey examine various aspects of Trump’s presidency, surveying his treatment of major thematic realms like ethics, rhetoric, and national security, with additional stops along the way to take up the Russia investigation and the ongoing impeachment saga. One such stop is the paradox of the “non-unitary executive,” which might also be filed under the label of the surprising weakness of an aspiring strongman.

Under our traditional understanding of the constitutional order, the president sits at the apex of the executive branch and appoints subordinate officials to carry out his will. These subordinates serve at the pleasure of the presidency and do his bidding or risk the axe. But under Trump, this unified top-down system has cracked. Subordinates regularly contradict the president or, conversely, the president regularly contradicts his subordinates.

Thus, the intelligence community says that Russia interfered in the 2016 election. Trump denies it and insists it was Ukraine. Trump claims he was surveilled by Barack Obama in Trump Tower. The FBI says nonsense: Nothing of the sort ever happened. Unmaking the Presidency offers a multitude of similar instances, including some in which bewildered White House staffers are compelled to scramble to reconcile established policy with Trumpian tweets. Among others, a flustered Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been caught more than once in the middle of these knots. Utterances by the president, Pompeo has insisted, are not the same thing as U.S. policy: “People make lots—I make lots—of statements. They’re not U.S. policy.”

Wittes and Hennessey suggest that this disunited executive branch may only be “temporary,” a feature of Trump’s erratic character, inattention, and sloth:

The executive has fractured only because Trump has let it fracture, because he tolerates a chaotic disunity that other presidents have not and that future presidents can choose not to tolerate. It’s hard to imagine, in fact, future presidents tolerating the kind of insubordination Trump tolerates daily, from which he seems to benefit so little and suffers so much.

But Wittes and Hennessey also hold out the alternative possibility of a future Trump-like repeat in which, in the absence of regular processes, subordinates act autonomously: “[T]he expressive presidency may have staying power and that lessened presidential control over the executive branch is, to one degree or another, an organic feature of the expressive presidency.”

Whatever the future holds, the upside for the moment is clear. The non-unitary executive has frustrated some of Trump’s more outlandish maneuvers. But there is a downside as well that Wittes and Hennessey point out. The disunited executive

risks cultivating habits in the bureaucracy of not doing what it’s told, habits far beyond those that have long made the executive branch a slow ship to turn. The consequences may be a presidency that will be much harder to manage in the future. Trump complains of a “deep state” that operates independently of the president. The slander has a quality of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

One area where the changes wrought by Trump might be particularly long-lasting concerns the administration of justice. The rule of law is one of the most fundamental features of a well-functioning liberal democracy. And in the United States, at least since Watergate, our Department of Justice has been renowned for its deeply ingrained culture of rectitude. Yet, as Wittes and Hennessey point out, the Department has turned out, under Trump, to be the “soft spot, the least tyrant-proof part of the government.”

The Justice Department has institutional defenses against the perversion of justice. There are formal rules, like the Levi Guidelines, that limit when and for what purposes the FBI can open an investigation. But the stronger constraints, at least in the past, have been informal “normative rules” about contacts between the Justice Department and the White House, along with the “behavioral expectations” of officials who have taken an oath of office. Vested with an enormous amount of prosecutorial discretion, the judicial machinery has functioned relatively smoothly in the post-Watergate era. But, as Wittes and Hennessey note, the machinery has an enormous vulnerability: “[A]n important element of our system presupposes a president who is fit to oversee it.”

In Donald Trump that fitness has been absent. The president’s conception of justice, as Wittes and Hennessey observe, is that of Polemarchus in Plato’s Republic, who posits that “justice is helping friends and harming enemies.” Repeatedly, we see this in action. Trump’s complaint, leveled in a tweet, that Attorney General Jeff Sessions was remiss in prosecuting two crooked Republican congressmen is a case of helping friends. His calls for the prosecution or imprisonment of his political adversaries, including both Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden, are notable examples of harming enemies.

Prosecutorial discretion and the informal nature of Justice Department independence have turned out, in Trump’s hands, to be a loaded gun pointed at the rule of law. Write Wittes and Hennessey:

Whether out of candor or—more likely—out of bombastic ignorance, Trump has never made the slightest pretense of respecting his highest prosecutors’ autonomy. The most remarkable feature of his behavior toward law enforcement is how overt it is. Where mid-century presidents struck a pose of virtue in public and quietly tolerated or encouraged abuses, Trump openly calls for abuses. . . . [He] not only merely assaults the specific norm itself; he is openly hostile to the value of nonpartisan and apolitical law enforcement that the norm seeks to protect. Trump’s behavior toward his law enforcement apparatus must count among his gravest breaches of the traditional presidency’s expectations.

To be sure, presidential perversions of justice are not unique to Donald Trump. Unmaking the Presidency walks us through the long history of abuses going back all the way to the actions of John Adams in prosecuting the editor of the Aurora under the Sedition Act of 1798. And Trump, they readily acknowledge, has not fully succeeded in corrupting the institutions under his control. Though damage has been done, careers ruined, morale undermined, a culture tarnished, to some important degree his lawless vision remains aspirational rather than realized.

But in one ominous respect he has succeeded wildly: his “simple demonstration of the idea that a president can involve himself in specific law enforcement decisions and not face immediate and catastrophic political consequences.” This is a demonstration that his successors will remember.

Wittes and Hennessey conclude their book on a pessimistic note. Trump may be a uniquely nefarious character but he is also the product of intense polarization “that will not go away just because he leaves the scene.” There is reason to worry, they continue, “that the damage Trump has inflicted on the office and its institutions is greater than it will appear on the day he leaves office.” This is not because Trump has succeeded in irreparably corrupting everything he touches but rather stems from his “thinking the unthinkable and [then] speaking it out loud.” The lesson a successor might learn is not never to do such things but rather “do them a little more quietly.” A smarter, defter version of Trump could prove to be the undoing of American democracy.

With impeachment hanging in the balance, it is impossible to make a confident assessment of which depredations wrought by the Trump presidency will prove to be enduring and which will prove evanescent. But in attempting to think seriously about such questions, Unmaking the Presidency, an admirable combination of historical understanding and subtle thinking, stands out as a singular achievement in the burgeoning literature about this troubled chapter of American life.

The post The New, Rotten Normal appeared first on The American Interest.

January 29, 2020

The Private Sector Acts on Climate Change

Lookin’ for love in all the wrong places: That’s what we economists have been doing to cope with the possibility, some say certainty, that the planet is heating up in response to human activity. We have been asking politicians to support a carbon tax which many of their constituents are loath to bear, and the benefits of which will not be realized until long after the politicians have retired from public life. In the process we are warning Americans, many of whom say they prefer socialism to capitalism, to fear the alternative of regulation and bigger government. They don’t. Silly us.

We have forgotten F.A. Hayek’s admonition that “nobody can be a great economist who is only an economist . . . the economist who is only an economist is likely to become a nuisance if not a positive danger.” As “only economists” we have become a bit of a danger by focusing policy debates almost exclusively on taxes that would induce consumers to curtail purchases of products associated with high levels of CO2 emissions. Although more and more politicians are giving us a serious hearing, few are willing to risk their futures by raising taxes, especially in the United States, where the President is unalterably committed to the proposition that global warming as a result of CO2 emissions is “a hoax,” perpetrated by “perennial prophets of doom and their predictions of the apocalypse” as he put it in Davos.

Trump did agree to have America participate in the planting of 1 trillion trees, not to reduce climate change but rather to conserve “the majesty of God’s creation.” As Marc Benioff, co-founder of Salesforce, put it, “the tree is a bipartisan issue. No one is anti-tree.”

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin suggested Greta Thunberg take lessons in economics. The teen Swedish climate activist is as certain we are heading toward global catastrophe as Trump is that climate change is a hoax. Such dueling certainties make the development of sensible public policy difficult.

Governments, however, are not the only players in this game: Private-sector players, acting in the jobs, capital, and product markets, matter. “We believe industry can deal with this issue on its own,” says Mnuchin, and perhaps it can, although what BlackRock CEO Larry Fink calls “realistic carbon pricing” would surely help.

Start with the jobs market. Americans not only buy stuff, they sell their labor. And they are increasingly unwilling to sell that labor, especially when it has a high skills content that gives them bargaining power, to companies that do not have strong programs that somehow comport with their “values.” Buyers in the tight and competitive labor market cannot ignore the preferences of the employees they seek to hire. Competitive pay and opportunities for growth, of course. But many tell interviewers they also want to feel good about what they are doing.

Which might well be one reason Microsoft, whose CEO Satya Nadella says, “Our employees will be our biggest asset in advancing innovation,” announced aggressive plans to become carbon negative—remove more carbon than it emits—by 2030, “both for our direct emissions and for our entire supply and value chain,” funded by an expansion of the “internal carbon fee” adopted in 2012. The company will deploy $1 billion of its own capital to develop new technologies “to help us and the world become carbon negative.” There’s more. Microsoft hopes “to remove by 2050 all the carbon the company has emitted . . . since it was founded in 1975.” Come work for us: We offer more than massages, ping-pong tables, and 24-hour healthy cuisine.

The market for capital is another in which concern about rising temperatures is now a factor. Fink has announced that BlackRock, which has $7.43 trillion under management, “will exit investments” that “present a high sustainability-related risk,” and vote against managements and boards insufficiently attentive to these risks. Whether he really believes such divestment creates “little downside” risk for BlackRock’s portfolio, or is merely “virtue signaling,” we cannot know. Let’s hope it is the former. “I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good,” wrote Adam Smith 244 years ago.

But we do know three things.

Some companies might possess assets that future regulations or taxes will sharply reduce in value. Others are exposed to severe weather and other events alleged to be the result of global warming. If investors are underpricing those risks, divestment is in Fink’s clients’ economic interests.

BlackRock’s plan to divest holdings in companies for which thermal coal production accounts for more than 25 percent of revenues exempts such large, diversified coal producers as Anglo American and Glencore. Coal divestments, reckons The Economist , come to less than 0.1 percent of BlackRock’s assets.

Fink can’t count on help from most bankers. They want no part in telling client-borrowers what environmental policies they should adopt in order to obtain loans.

We might add that we also know, or think we know, that hard-headed clients that entrust their money to firms such as BlackRock are concerned about the sustainability of the value of those investments. Fink is not alone in thinking that. Stephen Schwartzman, founder and CEO of the Blackstone Group, which has $554 billion under management, is reviewing the private equity firm’s portfolio to take account of sustainability. “Ironically, it ends up being good economics,” he told reporters in Davos.

In addition to labor and capital markets, consumer preferences might be operating against purchases of emissions-heavy products. Too much salt, or sugar, or fat, has prompted consumers to boycott a product. Many CEOs worry that association with a heavy carbon footprint will become a similar flashpoint, especially for climate-concerned millennials, who will pay more for a cleaner product even as they resist paying more to cover the cost of a carbon tax. To an economist who is only an economist this seems irrational; to a social scientist not so much.

In short, private-sector labor, capital, and product markets are doing some of the job economists have assigned to carbon taxes. This does not mean abandoning efforts to increase support for carbon taxes that confront consumers with the social costs of their consumption decisions. It means supplementing advocacy for that tax with policies that make labor, capital, and product markets even more effective in forcing reductions in emissions. Fink, Nadella, and their peers can use all the help they can get.

That help will, of course, not be forthcoming from the government if, as the odds now suggest, Trump’s lease on the White House is renewed. But despite the apocalypse-now crowd, this is a long battle. It is worthwhile gathering support for carbon taxes and banking it for later use, at which time the political class is likely to be in search of an alternative to both inaction and the spectacularly costly Green New Deal. This most efficient and least government-swelling of tools to cope with the risk of climate change would be on the shelf and ready for use.

The post The Private Sector Acts on Climate Change appeared first on The American Interest.

January 28, 2020

The Inquisitor

A rare moment of sanity—with an even rarer potential for good governance—emerged last month from the miasma of President Trump’s continuing war on the “Deep State.” After the Justice Department’s Inspector General reported that FBI investigators repeatedly misrepresented or withheld evidence from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court when they applied to wiretap Carter Page, a former Trump campaign adviser, the Court’s Chief Judge ordered the Bureau to reform the way it seeks permission to eavesdrop on Americans in national security cases.

For years, civil libertarians have warned about the lack of transparency and accountability in the FISA process. Targets almost never find out that their calls or emails have been monitored or what information the government provided to get permission to listen in. The FBI told the Court in early January that it would improve oversight and training, and there is some small hope for broader surveillance reforms–with Republicans who fiercely opposed or watered down earlier efforts now converted to the privacy cause (at least for this President).

Good news and good governance have a brief shelf life in Donald Trump’s Washington. Trump and his Attorney General, William Barr, immediately rejected the other big takeaway from the IG’s report: Despite the President’s charges of witch hunts, conspiracies, and treason, the FBI had a legal basis to open an investigation in 2016 into possible links between the Trump campaign and Russia, and the Bureau’s top leaders were not driven by anti-Trump bias. Even before the Horowitz report was completed, Trump and Barr had shifted their sights to the next investigation, this one headed up by Barr and his chosen investigator, U.S. attorney for Connecticut John Durham. At a Pennsylvania political rally the day after the IG’s report was released, Trump attacked FBI agents as “scum” and the Bureau leadership as “not good people,” declaring to a cheering crowd, “I look forward to Bull Durham’s report–that’s the one I look forward to.”

The Barr-Durham investigation is again focusing on alleged biases and misdeeds in the origins of the Russia probe (how many times before they get the answer they want?). But this one is also examining the January 2017 assessment by the CIA, FBI, and NSA that Russia interfered in the 2016 campaign with the goal of helping “Trump’s election chances when possible by discrediting Secretary Clinton.” There is no doubt what Trump is looking for: a declaration that Moscow played no role in his victory. Of course, his very best outcome would be a discovery that some other foreign power—Ukraine is the President’s preferred candidate—was the one really meddling in the election, on behalf of Hillary Clinton with the connivance of the Obama White House.

Let’s remember that the first favor Trump asked of Ukraine’s President Zelensky in their July 25th phone call was about the hacked DNC server he believes was spirited to Ukraine—it’s still in the DNC’s basement—telling Zelensky, “I would like to have the attorney general call you or your people, and I would like you to get to the bottom of it.” On Saturday’s opening day of Trump’s impeachment defense, Jay Sekulow, one of the President’s lawyers, argued that Trump was right “to inquire about the Ukraine issue himself,” rather than “blindly trust[ing] some of the advice he was being given by the intelligence agencies,” adding, “They kept telling you it was Russia alone that interfered in the 2016 election, but there is evidence Ukraine also interfered.”

In public, U.S. intelligence officials insist that they are getting all the support they need from the White House to do their work, including safeguarding the 2020 vote. But Trump’s solipsism and bullying are clearly taking a toll. Politico reported earlier this month that the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has been trying to persuade Congressional leaders to drop this year’s public testimony on the intelligence community’s annual worldwide threats assessment, for fear of again contradicting and infuriating Trump. When intelligence leaders testified last year that North Korea was unlikely to ever abandon its weapons and Iran was not cheating on the nuclear deal, Trump tweeted that they were “passive” and “naïve” and “Perhaps Intelligence should go back to school!”

If Trump gets even part of what he wants and a Barr-Durham report is crafted to feed public doubts about Russian election interference, Putin’s malign intent, or the reliability of U.S. intelligence analyses—all favored Trump memes—then U.S. national security will take a major hit: The Russian leader will be even more enabled in the midst of a new U.S. presidential campaign; U.S. intelligence partners even more unwilling to share information; and the American public even more skeptical of their government.

Durham—who had a reputation for even-handedness until he jumped out ahead of his own investigation and criticized the IG’s findings on “predication and how the F.B.I. case was opened”—has been closed-mouthed about any theories he might harbor. Judging from Barr’s public pronouncements, and his travel schedule (more on that below), he appears intent on proving once and for all the illegitimate origins of the FBI probe. (He has already accused the FBI of “spying” on the Trump campaign and declared that, “The president bore the burden of probably one of the greatest conspiracy theories—baseless conspiracy theories—in American political history.”) Whether he is also determined to “debunk” the 2017 intelligence community analysis on Russian interference, or just indulging Trump, is less clear, but there is certainly reason to worry.

Trump’s relentless attacks on his own intelligence services—and the recklessness with which he blurts out secrets in Oval Office meetings or tweets classified satellite images or the supposed name of the CIA whistleblower—has led key allies to question the continuing reliability of the U.S. intelligence partnership. The sight of Barr end-running the normal intelligence channels and expressing his and the White House’s contempt for their own Intelligence Community is further straining relations. On a trip to Italy this past summer, Barr went as far as asking Italian intelligence chiefs about possible nefarious activities by U.S. operatives on Italian soil.

The disbelief and rancor heaped on the Administration at home—including from some members of their own party—for the shifting justifications for the January drone strikes that killed a top Iranian general can be attributed to Trump’s own long-squandered credibility, the arrogance of their evidence-free briefing on Capitol Hill, and the fact that Trump and his advisors didn’t bother to get their public stories straight. But Trump’s attacks on the intelligence community have also taken their toll, especially with his base. Fox News host Tucker Carlson dismissed Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s trust-me-but-I-can’t-tell-you description of the imminent Iranian threat, telling viewers, “It seems like about 20 minutes ago, we were denouncing these very people as the Deep State and pledging never to trust them again without verification.”

Trump and Barr remain undaunted. In May, the President gave Barr the power both to declassify intelligence for the investigation and overrule any objections from the intelligence chiefs. Steve Slick, a former member of the CIA’s clandestine service and special assistant to President George W. Bush who directs the Intelligence Studies Project at the University of Texas at Austin, calls the move “alarming,” both because “it betrayed an instinctive lack of trust by the President, and likely the AG, in the integrity and loyalty of the intelligence agencies,” and because “declassification decisions made by inexperienced criminal investigators pose obvious risks to sensitive sources, fragile collection methods, and the confidence of foreign liaison counterparts.” In October we learned that the Barr-Durham probe has become a criminal inquiry, with the additional power to issue subpoenas.

Meanwhile, Barr has taken three trips to Europe, some with Durham, apparently to chase down a right-wing conspiracy theory, favored by the President and his most vocal backers on the Hill, about a CIA and Obama White House plot to deny Trump the presidency. As this story goes, the London and Rome-based professor, Joseph Mifsud, who told a Trump foreign policy adviser in the summer of 2016 that Moscow had “thousands” of hacked Clinton emails, was actually a western agent sent to entrap the campaign. The FBI probe was launched after George Papadopoulos told an Australian diplomat in London about the conversation and the Australians alerted U.S. officials.

In October, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, pummeled by his Parliament for authorizing his intelligence chiefs to meet with Barr, went public with the details, telling reporters that the U.S. Attorney General had asked about Mifsud’s relations with their intelligence agencies and also “to verify what the American intelligence did.” “Our intelligence is completely unrelated to the so-called Russiagate and that has been made clear,” Conte declared. Barr and Durham also took the show to London. And Trump called Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison to ask him to provide help. If our allies were consoling themselves that this is all Trumpian madness, Lindsey Graham, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, then sent his own letter to the leaders of Australia, Italy, and the UK justifying Barr’s efforts and claiming that the FBI and CIA “relied on foreign intelligence” to “investigate and monitor the 2016 presidential election.” The Australians immediately rejected the letter’s assertion that their London ambassador had been “directed” to contact Papadopoulos and to “relay information obtained from Papadopoulos regarding the campaign” to the FBI.

It doesn’t look like it will take much work to debunk the Papadopoulos-Mifsud conspiracy—assuming that investigators want the straight facts. Mueller and his team already did their own exhaustive legwork on Mifsud (and his Russian travels and contacts) and nothing factual has come out since to contradict what they found.

The more worrisome strand of their work is the investigation into alleged bias in the 2017 intelligence community assessment on Russian interference in the US election. According to The New York Times, Durham is taking a close look at the role of former CIA director John Brennan—one of the president’s most vocal critics, Trump moved to strip him of his security clearance in August 2018—requesting his call logs, emails and other records from the agency, and is particularly interested in whether Brennan championed the salacious and, we know now, hugely problematic Steele dossier as part of the finding. Brennan has denied that and all of the information that has come to light suggests he did the opposite. According to the Horowitz report, the CIA under Brennan “expressed concern about the lack of vetting for the Steele election reporting and asserted it did not merit inclusion in the body of the report. An FBI Intel Section Chief told us the CIA viewed it as ‘internet rumor.’” That said, Brennan’s overheated post-CIA performance—tweeting that Trump’s Helsinki press conference with Putin “was nothing short of treasonous” and writing in an op-ed that “Mr. Trump’s claims of no collusion are, in a word, hogwash”—has left him, and by implication the Agency, vulnerable.

Barr and Durham may also be probing for any differences in the intelligence agencies’ analyses in the 2017 finding. The CIA, NSA, and FBI all agreed with “high confidence” on the overall judgment that “Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at the US presidential election . . . to undermine public faith in the US democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency. We further assess Putin and the Russian Government developed a clear preference for President-elect Trump [emphasis added].”

But there was some difference on a second assessment that “Putin and the Russian Government aspired to help President-elect Trump’s election chances [emphasis added] when possible by discrediting Secretary Clinton and publicly contrasting her unfavorably to him.” According to the declassified version of the assessment, while “all three agencies agree with this judgment,” the CIA and FBI both expressed “high confidence”; the NSA (Durham and his investigators have reportedly met with former NSA Chief Adm. Mike Rogers several times) had “moderate confidence.” UT’s Slick says intelligence analysis remains “more art than science” and “it is perfectly normal, even routine, for two analysts or teams of analysts looking at the same intelligence reporting to assign a different level of confidence to a shared judgment.”

There is always a chance that the intelligence community got that part of the analysis wrong, although everything Putin has done since makes that very hard to imagine. It is very easy to imagine how “high” vs. “moderate” confidence can be spun to serve the Trump narrative. If, as has been reported, the IC’s source on Putin’s intentions was a Kremlin insider, it could be impossible for the Agency to push back in public.

It would be folly to sit back and hope that the already-considerable damage from the Barr investigation—and Trump’s wider assaults on the Russia finding, the intelligence community’s other analyses, U.S intelligence relationships, the list goes on—can be contained and the final report turns out better than signs suggest. Leaders of the IC need to fully commit to needed reforms—including confronting mounting concerns about politicization of intelligence analysis. And responsible members of Congress need to get back to their regular non-politicized oversight responsibilities. Admittedly none of this will be easy given the President’s penchant for firing top officials, Republicans’ enabling of Trump no matter how high the stakes or how obvious the offense, and the Democrats’ desire to score points against the President.

In the wake of the Horowitz report, FBI Director Christopher Wray has repeatedly drawn Trump’s fire, first for highlighting the IG’s finding that the FBI’s Russia probe was justified—“With that kind of attitude, he will never be able to fix the FBI, which is badly broken,” Trump tweeted—and then for admitting to the FISA application errors but not punishing “dirty cops.” “Chris, what about all of the lives that were ruined because of the so-called ‘errors?’ Are these ‘dirty cops’ going to pay a big price for the fraud they committed?” the President tweeted at his FBI director.

An expert on surveillance law appointed by the FISA court to assess the FBI’s reform plan has recommended additional changes. To restore confidence in the Bureau and the FISA process, the IG will need to go further and complete an in-depth review of many more FISA warrant applications to establish the full extent—and source—of the problems. If it turns out that errors in the Carter Page application are indeed widespread, then the Bureau’s announced fixes with the added revisions may be enough, although a recent op-ed in the Times by Cato’s Julian Sanchez makes a persuasive argument for why the Bureau needs to rework its procedures to address the problem of confirmation bias. Alternatively, if it turns out that the 17 errors and omissions and misrepresentations identified in the Page case are rare, then the Bureau may indeed have a serious problem of political bias that needs to be identified and rooted out. It certainly wouldn’t be the first time for the FBI. Trump’s relentless attacks are hyperbolic and destructive. But they mustn’t prevent a full investigation of what went wrong with the FISA applications—and a full effort to address the problems.

CIA Director Gina Haspel has managed to avoid Trump’s personal wrath (except for the threat assessment tweets, and that was a collective drubbing). But she should be seriously worried about the ongoing toll of Trump’s and now Barr’s assaults on her agency’s credibility and what further damage a Barr-Durham report might do. Placing the Attorney General and a U.S. Attorney in charge of reviewing/criminally investigating the 2017 intelligence community analysis has to send an especially chilling message to her analysts about the danger of not toeing the Trump line.

Haspel needs to address the fear—outside the CIA and in—that the CIA has been politicized either for or against Trump. As a first step, Haspel should review her predecessor Robert Gates’ 1992 speech to CIA analysts pledging to guard against politicization and the in-house survey that preceded it. With that historical cover, she could then launch her own survey to find out just how freaked out her own people really are—and follow up with her own strong public commitment to guard against politicization and protect their work and careers. Gates, the consummate Washington bureaucrat, acted after a bitter Senate confirmation hearing in which he was accused by former Agency colleagues of hyping the Soviet threat to please his masters. If Haspel thinks her own position is significantly stronger—or the current institutional necessity is any less pressing—she should also review George Papadopoulos’ Twitter feed in which her service as London station chief in 2016 plays a prominent role in the Mifsud entrapment conspiracy.

Congress also needs to get back into the business of serious oversight, rather than attacking or defending the intelligence community based on fealty to or animus toward Donald Trump. The Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee, and their chairman Rep. Adam Schiff, blew it with their unalloyed defense of the FBI’s FISA applications (rebutting a conspiracy-riddled memo from the then-Republican majority under Rep. Devin Nunes, a voluble champion of dark and outlandish theories). Schiff has admitted his error and now is otherwise engaged as an impeachment manager. But as the Chair of the House Intelligence Committee he can help improve the IC’s performance and bolster its credibility if he makes clear that it will no longer get a pass just because it is Donald Trump’s favorite target.

Schiff—and his far more bipartisan counterparts on the Senate Intelligence Committee—can start by holding long overdue public hearings on why the intelligence community failed to raise an early alarm about Russia’s assault on the 2016 elections. Moscow had been in the business of information warfare since at least 2008 and mounted a full-on assault in Ukraine in 2014. President Obama wasn’t warned about Putin’s plan to disrupt the U.S. elections until August 2016—a month and a half after the first tranche of hacked DNC documents were unleashed. In any other times, this would be called what it was: a major intelligence failure, one that requires a full public accounting to ensure that it is not repeated.

Whatever the Barr-Durham investigation comes up with, oversight hearings on the IC’s 2016 performance would also reinforce to the American public—and Moscow and Tehran and any other actors planning to interfere in U.S. elections—how seriously the U.S. Intelligence Community, U.S. law enforcement, and the U.S. Congress, if not the Trump White House, consider the threat. And how closely they will be watching in 2020 and beyond.

The post The Inquisitor appeared first on The American Interest.

Pompeo Should Go—and I Don’t Mean to Ukraine

Washington is consumed with the Senate impeachment trial this week, but it should also find some time to reflect on a sorry episode from this past weekend: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s behavior with NPR reporter Mary Louise Kelly. During an interview with Kelly in which he balked at discussing whether those State employees embroiled in the impeachment controversy—especially former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch—deserved an apology, Pompeo launched a profanity-laced tirade against the reporter for having the temerity to even ask such a question. He then issued an unbelievable statement the next day accusing Kelly of being a “liar.”

These actions undoubtedly played well to the audience in the White House, but they have done further, serious damage to the already battered morale in the State Department, and to U.S.-Ukraine relations, in tatters after the impeachment scandal. It wasn’t a great day in the United States for respect for the role of the press either.

Pompeo is scheduled to land in Kyiv this Thursday. He has canceled two previously scheduled visits—the first time because of the impeachment scandal, the second because of the crisis with Iran and attacks on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad. In light of his comments on Friday with Kelly, Pompeo should cancel again—and then he should resign as Secretary. To be sure, Secretaries are expected to support their Presidents, but Pompeo’s actions have taken that virtue well past the bounds established by his predecessors.

In the interview Friday, which started with questions about Iran, Kelly shifted to Ukraine and asked Pompeo whether he owed an apology to Yovanovitch, who was unfairly attacked by President Trump and Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s lawyer, among others, and removed last spring because of false allegations against her.

Pompeo refused to answer the specific question. “I’ve defended every single person on this team,” he said, responding in broad terms. “I’ve done what’s right for every single person on this team.” That would be news to most of those involved.

An aide to Pompeo ended the interview abruptly, and then called Kelly into Pompeo’s inner office, where the Secretary ripped into her for asking him questions about Ukraine, even though Kelly had alerted Pompeo’s staff that she would be doing so. In his typically bullying treatment of reporters, especially female ones, Pompeo challenged Kelly to find Ukraine on a map—which she did—and asked, according to Kelly, “‘Do you think Americans care about Ukraine?’ He used the f-word in that sentence, and many others.”

On Saturday, the State Department issued an extraordinary statement in the Secretary’s name, far and away the most juvenile and embarrassing statement under a State Department label I have ever seen. In it, Pompeo attacked Kelly, claiming she lied, not once but twice, and violated their after-interview conversation as being off-the-record, though he does not deny what she reported he said. He concludes the statement in way that probably won points at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue but that is beneath the office of Secretary of State, writing, “It is worth noting that Bangladesh is NOT Ukraine.”

Pompeo seems to be suggesting that Kelly, when challenged to find Ukraine on a map, mistakenly chose Bangladesh instead. Given her solid reputation, reporting experience, including from Russia, and her graduate degree in European studies, it beggars belief that Kelly pointed to a country far away on another continent.

Aside from attempting to bully journalists like Kelly, Pompeo has done an atrocious job of defending those who work at the State Department who have been ensnared in the impeachment controversy. When allegations surfaced earlier this month in media interviews with Giuliani associate Lev Parnas that Yovanovitch might have been surveilled by American citizens, Pompeo simply said in an interview with radio show host Hugh Hewitt that he had “never heard” of such reports.

In a separate interview with another radio show host Tony Katz that same day, Pompeo cast doubt on the allegations. “I suspect that much of what’s been reported will ultimately prove wrong,” an odd thing to say given that he previously claimed earlier that day to have never heard of the allegations.

He half-heartedly went on to state, without mentioning Yovanovitch by name, “but our obligation, my obligation as Secretary of State, is to make sure that we evaluate, investigate. Any time there is someone who posits that there may have been a risk to one of our officers, we’ll obviously do that.”

The Ukrainian government, by contrast, has shown more concern for the safety and welfare of Yovanovitch, a highly respected diplomat, than Pompeo has. Very soon after Parnas’s allegations surfaced, Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs announced that it was launching an investigation into the “possible unlawful surveillance on the territory of Ukraine of former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Jovanovich,” mentioning her, unlike Pompeo, by name. “Ukraine cannot ignore such illegal activities on its territory,” the statement added.

Since last fall, Pompeo has refused to defend Yovanovitch and other State employees unfairly slammed by Trump, Giuliani, and others for appearing before the House committees responsible for the impeachment inquiry. Instead, Pompeo attempted to block their appearance and refused to turn over any subpoenaed material.

Pompeo said nothing about Trump’s comment in his infamous July 25 phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelelnsky that Yovanovitch would “go through some things,” even though Pompeo listened in on that call. Michael McKinley, a top adviser to Pompeo, resigned after more than three decades of service to protest Pompeo’s “lack of public support for Department employees.”

Beyond damaging morale in the State Department by refusing to defend those who work there, Pompeo has fed discredited conspiracy theories that Ukraine interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. As a former director of the CIA, Pompeo is in a position to know better than to call for an investigation into such discredited theories. In his attack on Kelly on Friday, Pompeo made it clear that he doesn’t care about Ukraine and irresponsibly suggested that Ukraine doesn’t matter to the United States. Why would Zelensky and other Ukrainians want Pompeo to visit Kyiv after this latest indignity?

When he was a member of Congress, Pompeo was an outspoken critic of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton over the Benghazi tragedy in 2012 that cost four Americans their lives. When pro-Iranian militias attacked the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad last month, Pompeo supported a strong response. He has demonstrated he can come to the defense of his staff in certain circumstances.

But when it comes to Trump’s political fortunes and the President’s attacks and intimidation of people connected to the Ukraine controversy, Pompeo is nowhere to be found. He is not the first Secretary to seek to stay in the good graces of his boss. Secretary Colin Powell bowed to President Bush’s decision to invade Iraq and even made the case for it before the United Nations despite his own serious reservations about such a major move.

At the same time, Pompeo is arguably the most influential member of Trump’s national security team. James Baker may be the most recent Secretary of State with influence comparable to Pompeo’s, but Baker advanced weighty foreign policy objectives, including the Persian Gulf War, the reunification of Germany, and the collapse of the USSR.

Pompeo has handled some major foreign policy issues, too, including Iran and North Korea. But it is clear that Pompeo has decided that staying in Trump’s good graces politically is more important than doing the right thing, even when that undermines morale in his own building, plays into Russian disinformation efforts, damages U.S.-Ukrainian relations, and demeans the office he holds. On top of all that, Pompeo joins the ranks of those who demonize journalists who seek to do their job, holding officials accountable. Apparently Pompeo believes he is above accountability and a fan of freedom of the press only when journalists ask him softball or pre-cleared questions. I can’t think of a Secretary of State in recent memory with a worse relationship with the media.

I co-authored a piece in October in the Washington Post calling on Pompeo to resign. Since then, the need for his departure has only grown more urgent. Pompeo, however, has indicated he is staying on as Secretary, apparently forgoing at least for now, as many predicted, a run for the open U.S. Senate seat in Kansas. That is unfortunate for U.S.-Ukraine relations and for those who work at State. They deserve better.

The post Pompeo Should Go—and I Don’t Mean to Ukraine appeared first on The American Interest.

January 27, 2020

Trump, Clinton, and Defining Deviancy Down

Before Sunday evening, the odds of the Senate voting to remove President Trump from office were between slim and none. But news that John Bolton’s draft book directly ties the president’s intent to withhold aid to Ukraine in exchange for an investigation of the Bidens has moved those odds up just a bit. How much is difficult to tell at this point. But it certainly makes it more of a challenge now for senators to reject the idea of hearing from key White House witnesses.

To be clear, however, should Bolton and others testify, it is not as though they will be revealing something the senators don’t already privately know: that the president used the prospect of a meeting with the newly-elected president of Ukraine and U.S. aid to Ukraine as leverage to investigate a political rival in advance of the 2020 election. Similarly, most of them believe that the president’s sweeping claims of executive privilege to withhold papers and prevent the testimony of key witnesses have less to do with preserving an executive prerogative as a constitutional matter than blocking evidence that might be more damaging—something the Bolton news just reaffirms.

If the Senate vote ultimately falls short of the two-thirds majority required to oust President Trump from the White House it will reflect public opinion as of now. A slim majority currently thinks the president should have been impeached and removed. But polls also indicate that, while most Americans think that the president’s actions were wrong, they do not rise to the level of seriousness that the Senate should remove the President from office. In short, at this moment, the Senate seems to be in lock-step with the public.

We’ve seen this before. In the Clinton impeachment, most Americans believed the President committed perjury by lying under oath about the Monica Lewinsky affair and then acting to cover it up. And while a majority was willing to see him officially censured for his behavior, and hence obviously believed he had misbehaved, public support for removal was too weak to have moved the Senate to vote otherwise.

Given the level of partisanship involved in both cases, it could be argued that the two impeachments will have ended about where one would have expected—and even correctly so. In Clinton’s case, the argument was: Yes, his actions were wrong, but they were the product of a kind of human frailty that is common and often forgiven. Indeed, if there were true victims, it was Hillary and their daughter Chelsea.

As for Trump, the more sophisticated of his supporters will say: Of course he used the office for political purposes, but that’s no different than any president seeking reelection from time immemorial. Administrations will pick (or not) this or that policy, chose to enforce (or not) this or that law because it might play well (or not) in some key state. Why be holier than thou now, particularly with an election less than a year way?

The Senate tries impeachments because the Constitution’s framers believed it would bring, among other things, a political sensibility to bear on these matters. And the requirement that it be a Senate supermajority to remove the President implies that such a decision be unequivocally compelling.

Nevertheless, the precedents set by the “acquittal” for Clinton and, possibly, for Trump can’t help but have knotty implications.

Although the Clinton “war room” was able to publicly frame the House GOP’s and Ken Starr’s impeachment effort as some perverse obsession with sex, the President had in fact committed perjury and tried to obstruct a legally constituted investigation. Both actions were in violation of his constitutional duty to “faithfully execute the laws.”

As for President Trump, it’s true that other presidents have played politics while sitting in the Oval Office. But what president has gone so far as to essentially bribe a foreign government to assist him in taking down a possible domestic opponent with promises of a meeting and already promised aid? This is, one would think, an affront to the president’s oath to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution,” which among other things surely includes protecting the integrity of the electoral system.

As a pair, Clinton’s acquittal and Trump’s will set a bar for removal that suggests “a little” wrongdoing by a president will be judged okay. Whether this low bar is what the framers had in mind is an entirely different question.

In the debate in the First Congress over whether the president has an implied constitutional power to remove senior executive officials from their posts, James Madison beat back attempts to say that the removal power was the Senate’s and the President’s combined, or that it was a matter for Congress to write into legislation whatever mechanism for removal it saw fit. Thus Madison, the very “Father of the Constitution,” in one of the most important first inter-branch debates, defended the unitary character of the presidency as essential for the President to be able to carry out his duty to see that the laws are faithfully executed. Yet in this very same debate, Madison also notes that an impeachable offense and grounds for removal would include “the improper continuance of bad men in office” and “the wanton removal of meritorious officers.” Neither of these offenses, as described by Madison, involve bribery or treason. They must have fallen in his mind under the category of “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” It’s not difficult to conclude that our contemporary tolerance for “a little” wrongdoing by presidents is difficult to square with the delegates’ intentions when they adopted the phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” in the waning days of the Constitutional Convention.

It’s arguable that keeping the bar for removal higher is prudent, if not strictly speaking constitutionally accurate. Given current levels of partisanship and polarization in the body politic, to do otherwise might result in open season on every new chief executive. But given how presidents of both parties have come to view the discretionary authorities of the Oval Office, it’s also possible that the result of Clinton’s impeachment and the likely result of the Trump impeachment are licensing further problematic behavior. Certainly in the immediate case of President Trump, how probable is it that he will be chastened by his impeachment? Rather, he may well turn a favorable vote in the Senate into a mandate to be even more aggressive in the use of his powers, and become even less likely to countenance congressional oversight of any note.

Finally, a Senate vote that falls short of the two-thirds majority will likely cement what most Americans will accept as tolerable behavior on the part of presidents. At a time when both left and right are bemoaning the decline in America’s civic culture, are the lessons learned from both the Clinton and Trump impeachments salutary? If the split in the population on these matters weren’t so strongly along party lines, it might be possible to have a forthright conversation about what to expect (or not) from modern politics and today’s politicians. But that is nowhere to be seen in the Senate trial so far. Perhaps witnesses will change that dynamic. But, in the meantime, what we are left with, to paraphrase the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, is two impeachment cases defining presidential deviancy down.

The post Trump, Clinton, and Defining Deviancy Down appeared first on The American Interest.

American Politics Change, But American Parties Endure

The Constitution of the United States makes no mention of political parties. America’s first president, George Washington, abhorred them. He spent a large part of what turned out to be his most influential presidential message, his Farewell Address of 1796, warning the country against the dangers of what he called “factions.” Yet Americans ignored that warning and developed, soon after his presidency ended, two major parties. The country has had two major political parties almost continuously ever since. Moreover, it is difficult to imagine American democracy, or indeed democracy anywhere, functioning effectively without such parties to connect citizens to the government and to structure elections and legislative proceedings.

For that reason, the current distress that major parties are experiencing across Western democracies is cause for concern. In recent years, in Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy, the parties that have dominated the political landscape since World War II have weakened, in some cases to the point of disappearing, without being replaced by new parties with the demonstrated capacity to govern. The troubles extend to the United States. Donald Trump, for much of his adult life a Democrat or an independent, seized the Republican nomination for President in 2016, won the office, and has carried out policies, such as trade protectionism, that almost all Republican officeholders had previously opposed. A leading candidate for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, is not a Democrat. He calls himself a democratic socialist and one of his best-known supporters, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, has said that in a European political system she and one of Sanders’ principal opponents for the nomination, former Vice President Joseph Biden, would not belong to the same political party.

Are the Republicans or Democrats or both headed for fragmentation or oblivion, and the American political system therefore destined for disruption or even chaos? In his lucid, concise, and deeply informative new book, How America’s Political Parties Change (And How They Don’t), Michael Barone provides the basis for a clear answer to those questions: No. As a leading authority on American politics and political history, the coauthor of an indispensable guide to the subject, The Almanac of American Politics, and the author as well of several well-received books about American history and politics, Barone knows whereof he speaks.

He points out that the country’s two political parties have proven to be unusually durable. The Democrats date from the 1830s and are the lineal descendants of Thomas Jefferson’s Republican-Democratic Party, which was founded in the 1790s. The slightly younger Republicans began their formal existence in 1854, and inherited policies and members—notably Abraham Lincoln—from the Whigs, a party that began in 1833.

The two have survived in part because of American electoral laws, which favor the existence of two and only two parties by making it very difficult for smaller ones to win elective offices. They have managed to persist as well because, down through the decades, each has retained a basic feature. The Democrats have represented the interests of what Barone calls “out-groups,” who have felt themselves marginalized in, and often in some ways excluded from, American society. In the 19th century these groups sought to protect their interests by limiting the reach of the government. In the 20th and 21st centuries they pursued the same goal by expanding government’s scope. The Republicans, by contrast, have historically assembled the “in-groups,” who have felt generally satisfied with the country’s social, economic, and political arrangements but have often regarded these as under attack and in need of defending. Finally, and crucially, both parties have proven to be flexible, able to adapt to new challenges and welcome new groups to their coalitions.

They have had to be flexible in order to survive because America has changed, frequently and substantially, since the mid-19th century. Three kinds of changes in particular have reshaped the parties. Individuals have changed their political ideas and moved from one party to the other. The most prominent 20th-century example is Ronald Reagan, who as a young man staunchly supported Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal but later became dissatisfied with the Democrats’ approach to governance and ultimately served two presidential terms as a conservative Republican.

In addition, new challenges have arisen, to which the parties have responded in ways that have both lost and gained them support. In 1920, for example, with Woodrow Wilson’s hopes for post-World War I peace based on American membership in the League of Nations shattered, with inflation raging, and with widespread strikes interrupting economic activity across the country, Wilson’s Democrats suffered one of the most crushing defeats in American electoral history. Only 12 years later, however, Herbert Hoover’s perceived failure to respond adequately to the Great Depression led to a sweeping victory for the Democrats and Franklin Roosevelt. In 1980 it was the Democrats’ turn to pay the price for ineffective economic policy as, in the face of double-digit rates of unemployment and inflation, Ronald Reagan won the presidency by a wide margin. On each of these occasions, voters shifted their partisan allegiances in substantial numbers.

A third kind of change has had long-term consequences for America’s two political parties. Over time, entire groups—or at least many of their members—have altered their political affiliations. Donald Trump and John F. Kennedy are seldom seen as similar political figures but both won the presidency by attracting votes in large numbers from northern and midwestern workers without college educations, and from white southerners. In the 56 years between 1960 and 2016, because of the upheavals in American public life, these voters had come to see the Republicans as more reliable defenders of their interests than the Democrats.

The exodus of liberals from the Republican Party and of conservatives from the Democrats count as the most significant group defections of the last 50 years. Both are usually attributed to the rising political salience of race, due to the civil rights movement, and while not denying the importance of this issue Barone cites two other important causes: In the middle third of the twentieth century liberals were Republicans, he says, in no small part because they disliked the southern segregationists, the corrupt bosses of large northern cities, and the sometimes less-than-honest union leaders who played key roles in the Democratic party. When all three either disappeared or lost much of their influence, Republican liberals felt free to become Democrats. As for Democratic conservatives, the author points to foreign policy as a reason for their switch in party loyalty. The south is the most hawkish part of the country, and during the Vietnam War the Democrats became the dovish party, driving southerners into the Republican ranks.

Through all the changes that have taken place in American history over the last 150 years, one feature of the political system has remained constant. While the two major parties have not been able to retain the allegiance of all their supporters all the time, they have demonstrated sufficient flexibility to adapt to new circumstances and thus to remain viable national coalitions. In this way they have sustained the ruling duopoly of American party politics.

Of greatest immediate interest in a presidential election year is the balance of power between the Republicans and the Democrats. Barone finds that, by historical standards, the two parties are now very evenly matched: Neither enjoys a dominant electoral position. For this reason, How American Parties Change (And How They Don’t) does not attempt to predict the outcome of the 2020 election. On the basis of the book’s survey of the nation’s electoral history, however, it is possible to make a prediction with some confidence about 2070: fifty years hence the Republican and Democratic parties will still dominate American politics, but in their membership and their positions on the issues of the day, they won’t look the way they do now.

The post American Politics Change, But American Parties Endure appeared first on The American Interest.

January 24, 2020

Overdoing It, with Chinese Characteristics

Having paid our due to President Coolidge, we now turn to an informal Navy Seal motto to help us fathom Singapore the improbable. Articulated by, among others, Admiral Dennis Blair and adumbrated by David Brooks, it goes like this: “We’re Americans: Anything worth doing is worth overdoing—and at great expense.” Amusing, sure; but what does it mean?

For present purposes, it means that if you combine a technocratic juggernaut manned by well-trained, coherently led personnel with expansive mission mandates defined by higher political authorities, you will, at least from time to time, defeat any balancing gyroscope designed to keep it from running off the rails. There will be excesses. Mistakes of commission will outnumber mistakes of omission. Adjustments will ensue, but so long as the juggernaut remains in motion with political endorsement, a rinse-and-repeat pattern will emerge.

Navy Seal operations fit the category, which is why civilian overseers festoon its subculture with lawyers—as they should, whatever the resultant warrior frustrations. Singapore’s administrative technocracy fits the category too, for similar generic reasons and other reasons special to its circumstances. In short, like the U.S. Special Ops community, most of the time it’s admirably efficient, but when it isn’t, it isn’t in a characteristically “overdone” way. Specific examples will follow next time, but before examples can sum to make overall sense they need be set in an intelligible framework. That’s today’s labor.

Generic reasons for any technocracy’s overdoing things include those associated with the intrinsic nature of elitism. The corporate-minded folks who run the Red Dot (a.k.a. Singapore) consist of the high ranks of the People’s Action Party and the senior managers who direct its ministries, agencies, and two sovereign wealth funds. To give an extreme but not entirely uncharacteristic example of the tightness of this networked and not infrequently family intermarried elite, the CEO of Temasek is the wife of the current Prime Minister (who is the son of Singapore’s first and most illustrious Prime Minister). Ho Ching and Lee Hsien Loong—although several rungs down the ladder from the late iconic duo of Lee Kwan Yew and Kwa Geok Choo—are Singapore’s current power-political couple; when they walk together arm-in-arm, small explosions issue from the heels of their shoes.

Similar connections run vertically through generational time. A recent long-serving Deputy Prime Minister, Teo Chee Hean, is the great-nephew of Teo Eng Hock, one of Singapore’s most prominent late 19th-early 20th century Teochew business and political figures. Family and dialect-group/clan connections among ethnic Chinese Singaporeans, called guanxi, represent deep reservoirs of bonding social trust. It is a trust based on common values and protects against selfish rogue actors ending up in high positions where they could do much harm. It is not to be confused with crude nepotism; nor does it negate Singapore’s fealty to meritocracy that opens high positions in private and public sectors to Indians, Malays, and others who make the grade. But at the very top of the interlinked business/political elite, these connections do skew it. Hence, no sentient adult here thinks Singapore will have an Indian or Malay Prime Minister any time before the orchid display in the Botanical Gardens freezes over.

There is a Malay President who happens also to be a woman, Halimah Yakub. It would be churlish to stigmatize her as a token; she is able and accomplished. But she attained her mostly ceremonial office accompanied by a kind of rigging: the PAP elite’s warping and winding the constitutional law stipulating who can become President and how. It’s no stretch, therefore, to characterize her elevation into office from a PAP loyalist into an obligatory party-unaffiliated President as managed symbolism.

The symbolism itself was arguably a sensible aim. But did the method exemplify overdoing it—too much stage management veiled by too thin a wizard’s curtain? Depends who you ask, but just about everyone agrees that Yakub would have won handily even without any special efforts courtesy of the PAP brain trust.

All insular and confident political elite clusters tend to generate a sense of privilege—earned privilege, perhaps, but privilege all the same. When coupled with the longevity of high status and a perception of success at doing the “job,” a certain rigidity of personality, defensiveness about criticism, and, at times in some people, arrogance about their own presumed infallibility can result. It can also lead to a belief that the über-elite are entitled to warp and wind the law to their own purposes. The tendency isn’t new: See II Samuel, chapter 12, for an example concerning King David and a family friend named Nathan.

The keenest American interpreters of this compound condition in the United States have been members of the Adams family (no, not that Addams family…). First from President John Adams:

Power always thinks it has a great soul and vast views beyond the comprehension of the weak; and that it is doing God’s service when it is violating all His laws.

Next from his great-grandson Henry:

No man, however strong, can serve ten years as a school-master, priest, or senator and remain fit for anything else. All the dogmatic stations in life have the effect of fixing a certain stiffness of attitude forever, as though they mesmerized the subject. . . . The effect of power and publicity on all men is the aggravation of self, a sort of tumor that ends by killing the victim’s sympathies, a diseased appetite, like a passion for drink or perverted tastes.

No cloistered elite is safe from such infirmities of mien and mind. The circulation of elites generally and the rotation of political leadership in particular are preventatives against ingrown insularity, arrogance, and, as Henry Adams put it, “the killing of sympathies” in any mature political order.

Is Singapore’s present political elite afflicted by such debilities? Can there be such a thing as too much bonding social trust, such that an elite can become excessively confident in its own judgment? Let me remind you that Singapore contains multitudes, and that nothing here is simple. The answer, alas, depends on who is asked the question.

Which begs a better question: What are the historical and cultural facets of overdoing it, in part at least, “with Chinese characteristics”? Since I am not and never will be expert on anything Chinese, I rely for parts of an answer on Singapore’s 89-year-old sage Wang Gungwu—whom I have read, known, and worked with now and again for 25 years. For present purposes, three insights demand a hearing.

First, the paternalistic nature of leadership in Singapore owes much to a path dependency planted amid its 1965 origin, and it has little to do with anything culturally Chinese. When Singapore was thrust into independence against its will, the leadership faced a parlous situation in which maintaining social order and political control was paramount. Traumatic 1964 race riots were vivid in their working memory. The trauma of the 1942-45 Japanese occupation was still felt, partly in the form of the psychological shock of the sudden, ignominious dethronement of British superiority that rattled the self-confidence of the Chinese elite whose members had modeled themselves as Westernizing Anglophones.

In the mid-1960s, too, the country still deserved “the world’s largest slum” epithet, and the recent withdrawal of the British from the naval base at Sembawang had left an unsolved employment crisis in its wake. And Maoist China loomed nearby, at work avidly infiltrating labor unions across the region as well as in Singapore itself, an effort that contributed to cataclysmic civil violence in Indonesia the same year Singapore was thrown into independence. That same year, too, in February, U.S. Marines hit the beach at Da Nang to prevent South Vietnam from being communized by force of arms.

If all that were not enough, the Sukarno government in Indonesia had opposed the creation of a “greater” Malaysia—one that included parts of Borneo as well as Singapore. During the Konfrontasi of 1963-66, bombs went off here as an offshoot of that complex disagreement from hell. Under such conditions, the notion of introducing multiparty democracy seemed a formula for ethnic-based civil war, external intervention, and near-instant oblivion.

But second, yes, Singapore’s paternalistic political culture does owe also to the Taoist/Confucian prism that splits civil light into the colors of Chinese culture. It is a deep shaping factor that is much more powerful than a mere two generations of Anglophonic affections and affectations.

At least as much as China itself these days, whose intellectual traditions have been whipsawed by forced-march Marxism-Leninism and its partial relaxation, Singapore’s elite prizes orderliness above all else. There is right and wrong, diligence and laziness, loyalty and disobedience. Despite the existence in the Analects of a right to oppose unrighteous, ruinous rule, history has bequeathed the de facto obligation that authority and expertise are due respect and honor. There is, in short, a natural hierarchy inherent in all things that guides virtuous behavior, and in that hierarchy all things fit together. Reality exudes symmetry. Ambiguity and loose ends make some people in all cultures nervous, but in Confucian-accented Singapore, those personality types dominate.

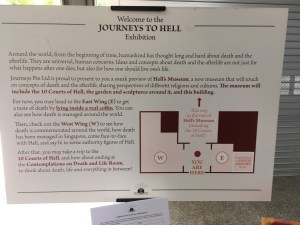

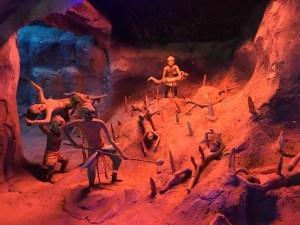

A vivid if weird attestation is Haw Par Villa, an eight-acre art-diorama park developed largely around the theme of hellfire and damnation, Asia style. Dating from 1937, courtesy of the brothers who invented Tiger Balm, the place is surreal in a specific way: It is a deliberately over-the-top extrapolation of the sacred statuary and related art styles one finds in Taoist/Buddhist temples and shrines. One Haw Par exhibit takes you through a tunnel displaying the ten courts of hell. In each court, a Mandarin matches sins to specific punishments, which are illustrated in roughly one-fifth scale miniature before you. It is the orderliness of the surreality that is striking.

The hellish lore is a mash-up of Taoist, Hindu, and Buddhist legends, in keeping with the syncretism of typical Asian approaches to religion. Buddhism comes out of Hinduism and most Taoist temples here have Buddhist rooms or sections. Adepts mix and match deities and supplications as suits the moment. Confucianism functions as a trans-ritual ethical umbrella, for East Asian traditions do not join faith and philosophy, ritual and law, in the same ways that the Abrahamic faiths do.

Another illustration of the general point can be gleaned from something as anodyne as a high-end restaurant experience. At most very high-end Western restaurants, menus offer at least some choices. At nearly all very high-end East Asian restaurants, chefs dictate what is best among the foods available, and know how to cook and present them. Both a Westerner in a high-end Western restaurant who refuses to choose and an Easterner in a high-end Eastern restaurant who deigns to choose are inexplicable in their respective cultural contexts.

This difference echoes across political cultures: Multiparty politics and wide-open elections are menu-like; one-party paternalistic systems are not. Asian democracies are unlikely ever to fully mimic Western types, whatever other reasons may also explain differences.