Michael Sudduth's Blog, page 2

July 10, 2016

Stephen King and the Path of Fiction

I’ve spent most of the past twenty years playing conceptual chess and solving logical puzzles, an essential part of my work as a professional philosopher. Like finding your way out of a labyrinth, that can be fun, especially if you don’t take it too seriously. But other modes of discourse, exploration, and expression have also played a prominent role in my life, mainly music, poetry, and story telling. And in my most challenging hours, I’ve always turned to music and creative writing, not analysis and logic chopping.

During the past decade I have on different occasions happily digressed from scholarly projects to explore fiction writing, something I first broached with the writing of zombie stories in my teenage years. And in the past three years, I’ve regularly supplemented my scholarly writing with contemplative writing and poetry, some of which I’ve published in my blog. In the past eleven months, though, I’ve returned to fiction writing. It’s been a very sustained and concentrated effort, inspired largely by Stephen King. Here I offer some reflections on my movement into fiction, King’s role in it, and what I’ve found beneficial about this new direction in my writing.

My Return to Fiction Writing

Some very unusual experiences while living in an 1817 home in Windsor, Connecticut inspired my first attempt at writing a novel. That was back in 2008. The storyline of the novel emerged from two situations that kept popping up in my head. The first was a very ordinary one: what if a young widow bought an old house and started restoring it, as a way of working through grief after the death of her husband. The second situation was a paranormal one: what if place can absorb and retain the memories and emotions of people who reside there? These two situations gave birth to an interesting story that linked a young woman’s pursuit of psychological healing, a retired philosophy professor’s newfound life as gardener, and the Connecticut witch trials.

I never finished the novel, but the hundred pages I wrote represented my first serious exploration of fiction writing since my teenage years. Back then I wrote zombie stories. That was a great way of throwing some water on the flames of teenage angst. It was also a nice way to exact a little poetic justice on the asshole jocks in junior high and the stuck-up cheerleaders who didn’t give me the time of day. My friends and I had a good laugh, and—perhaps most importantly—no one got hurt.

My early exploration of fiction writing was also something of a tribute to George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. I must have watched that film with friends over hundred times by the time I graduated from high school. We had the entire script memorized. That movie was simply the shit.

In high school my creative expressions shifted to music. After starting a heavy metal band in the 1980s, the writing of zombie stories gave way to lyric writing. The zombies were still alive, but they walked in a larger supernatural field with vampires, ghosts, and demons.

In the past year, I’ve returned to fiction writing. I have two novels and a novella underway. Each story explores dissociative psychology. One is a straight psychological thriller; two involve ostensible paranormal phenomena and explore the ambiguity between such phenomena and abnormal psychology. I’ve nearly completed one of them—Shadow at the Door. I’ll have more to say about this in a future blog once the novel is complete.

Inspiration from Stephen King

Why have I returned to fiction writing?

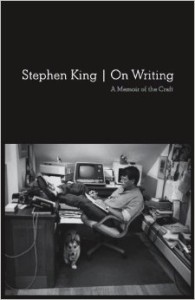

Late last year I happened upon Stephen King’s On Writing (2000) while perusing books at a Barnes and Noble bookstore, appropriately the same venue where eight months later I’d participate in a Q&A with King himself. A protracted moment of lucid disgust with academic philosophy led me to wander aimlessly through the store. I eventually wandered into the fiction section, and there I saw Stephen King’s On Writing. “Oh yeah, King,” I thought. A series of images lit up my mind—Jack Nicholson slashing through a bathroom door with an ax (Here’s Johnny!), Kathy Bates hobbling James Caan’s cockadoodie legs, and Sissy Spacek using psychokinetic powers to seriously fuck up her cruel high school peers.

I picked up the book and began reading it. Within minutes it melted away my disgust with academic philosophy. In fact, it melted away academic philosophy altogether. What a rush!

It only took five pages to persuade me to buy the book, which was so enthralling that I completed reading it in two sittings. On Writing is a brilliant and inspirational memoir-style exploration of fiction writing, though I think there’s something in it for any writer. And from On Writing I went on to read King stories for the first time—Salem’s Lot, the Shining, Misery, Bag of Bones, A Good Marriage, and a dozen King short stories.

One of the strengths of King’s writing is his ability to reveal that ordinary life is thin and fragile, like the sheet of ice that covers a lake in thawing season. It doesn’t take much for the ice to break and for us to fall through. The abyss is not far away, and our deeper fears are actually very close to the surface of ordinary life. King’s stories allow us to confront these fears but also to develop a certain liberating relationship with them. I think there’s a certain playfulness there that helps us feel more confortable in our skin, darkness and all.

A precondition of this playfulness is an unobstructed transparency about the human condition, and this is a signature of King’s writings. He holds back nothing, and he represses nothing. This allows light and darkness to each break out. And there’s no apology for letting the dark express itself, even if the darker side of human nature wins on occasion. “Monsters are real, and ghosts are real too,” King has said. “They live inside us, and sometimes, they win.”

One must already be okay with the darker side to be fully transparent about it. We hide what we cannot tolerate about ourselves, and that tends to be what we condemn in others. Shame and guilt are the gatekeepers of unsettling truths. Those gatekeepers are rather stingy when it comes to divulging our deeper secrets, even to our selves.

But therein is the magic of King. He busts it all open. He drops you into the abyss, but there’s something redemptive about it. King once said, “Good writing—good stories—are the imagination’s firing pin, and the purpose of the imagination, I believe, is to offer us solace and shelter from situations and life-passages which would otherwise prove unendurable” (Nightmares and Dreamscapes, 6).

The point can be expressed in more positive terms. We might say, with a dash or two of metaphor, that writing opens space large enough to allow our laughter and our tears to be and to dance together. In that dance we don’t merely disclose life’s larger movement. We actually unite with it. That’s redemptive, but it’s not an escape from the dark. It’s a reconciliation to it. It’s Zen on a magic carpet ride.

I’ve always found the dark fascinating and liberating. So it’s no surprise that I should connect with Stephen King stories. This also explains my teenage attraction to the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, and the lyrics of heavy metal bands like Black Sabbath. Of course, it also helps to grow up in the dark—Vietnam, Watergate, the proliferation of serial killers, the rise of horror films, and the threat of nuclear holocaust, if the “big one” didn’t shake, rattle, and roll California into the ocean first. And religion comes in here too. To some extent, I found Christianity appealing in my later teens and early twenties because it acknowledged the more potent devils of our nature.

So King ignites something fairly deep in me. And as a catalyst in my movement towards fiction, he’s really guided a return to something that was very alive for me years ago. Things that were once very alive for us sometimes come back, sometimes many times. They’re not done with us yet. They have something more to say, something more to do, and there’s some new transformation or development awaiting us.

Three Benefits of Fiction Writing

Fiction writing can facilitate personal development and transformation in different ways. Here I’ll just mention three that are particularly significant to me, especially since they stand in sharp contrast to philosophical writing, at least of the sort I’ve practiced for twenty years.

First, fiction writing, like all expressions of creativity, helps loosen the grip of the ego. Fiction invites us to write as unconsciously as possible, just like music invites us to play an instrument or sing as unconsciously as possible. To some degree the process releases the chokehold of the ego, that is, our attachment to a distinct set of interests, expectations, and beliefs—you know, all that thinking that mediates the toxicity of our lives.

By contrast, scholarship and argumentation are very much about a consciously adopted point of view. There I try to make a point, or many if my reader is very unlucky. Even when I’m doing analysis, I’m keeping track of the number and color of the cows behind the fence, how many times they’ve taken a dump, and where the piles of shit are located. The less conscious I am here about what I’m doing, the worse off I am. No scholar likes to step into a pile of shit after all.

Fiction writing moves in the other direction. Throwing oneself far enough into any creative process is similar to the Buddhist experience of “no self.” You can’t be too conscious of what you’re doing while you’re doing it or you’re not going to find any deep satisfaction in it, and you’re also unlikely to do it well. I still remember the three months I worked as an apprentice for a house painting company. Every time I flubbed something on the job, my boss would say to me, “you’re thinking about it too much!” He was right. At any rate, I was too much in thought.

When I’ve been most effective in playing guitar or sports, I wasn’t thinking about what the hell I was doing. And whatever thinking might have been going on, was little more than a ballboy on the sidelines. I wasn’t in it. You have to move from the center, recede into the background so to speak; maybe disappear altogether. That’s the nature of art, whether it’s painting, music, or writing.

The selflessness of the artistic process takes a variety of concrete forms in writing. For example, I have to trust my characters more than myself. I wait for them to say and do things. It’s intuitive writing. In a certain sense, I’m just watching things play out in my mind and writing down what I see happening. The characters, not my conscious intentions, play the deeper role in shaping the development of the story. And it takes a certain amount of cultivated patience to just go with the flow when the characters have something to say or be at rest (take your fingers off the keyboard) when they’ve fallen silent.

When I tell people I’m writing a novel, they want to know what the plot is. I tell them, I don’t have one. That’s truthful, and of course it’s also a good way to get out of talking about your story. Some fiction writers do plot. I’ve done some of this myself, years ago. It’s just not how I do things now. The writing is now more situation-driven, as King often describes it. And the dynamic is entirely different.

Of course, I understand that some people need a meticulous outline of the details of their story worked out in advance, just like some people need to paint by numbers. What’s your plot? Have you identified the antagonist(s) and protagonist(s)? Have you planned the story arc in the right way? Have you avoided head-hopping? All those nagging questions, which, for me, just sound like a good way to distract from story writing. I personally prefer just to write the story, let that flow, get in that zone. There’s plenty of time to address technical questions later and do the needed clean up.

And here’s one of those many points where Stephen King’s observations resonate with me:

I distrust plot for two reasons: first, because our lives are largely plotless, even when you add in all our reasonable precautions and careful planning; and second, because I believe that plotting and the spontaneity of real creation aren’t compatible . . . I want you to understand that my basic belief about making stories is that they pretty much make themselves. (On Writing, 163)

In the writing of my current novel I’ve seen how a story can make itself or be the direct product of what the characters are doing in a very spontaneous manner, without much or any foresight on my part. Over and over, I’ve found myself writing scenes or dialogue that I had no idea I’d be writing until the sentences were being typed. And even where I have some bare bones idea of where things may be going, when the characters clothe it with flesh and blood, there’s still considerable surprise. Nor is the result chaotic or incoherent. What’s amazing is the level of inner coherence that emerges when there’s been no conscious intention to create it. I personally find this more enjoyable than merely filling in the details of an outline.

What is important is that I feel the movement of the story, and that means listening to my characters tell the story. And it’s important not to “push the river.” To the extent that I’m trying to achieve something with the story, I’m not listening to my characters tell the story. And to that extent, I can’t even hear the voice of my characters, much less see them evolve with the story, and that’s all essential to a good a story I think.

Second, there’s a sense in which fiction writing possesses the power to disclose aspects of our inner life, not immediately transparent to us. Someone once asked Albert Camus whether he appears in his own novels as some particular character. He said, no; he’s actually all of them. Arguably, every character is some part of the author (maybe some are a bigger part of us than others), but the salient point is that those parts come into clarity in the process of writing, even if it’s only at the completion of a work or in subsequent reflection on it. And that means there’s quite a bit of self-knowledge delivered in the writing of a story.

Stephen King has often said that while he was writing the Shining, he wasn’t aware that, in writing about Jack Torrance, he was in fact writing about himself. King was the alcoholic struggling for redemption but slowly losing his mind. That hit him later, no doubt in part because the novel became a mirror that enabled him to see his own face more clearly. Hence, King says, “I think you will find that, if you continue to write fiction, every character you create is partly you” (On Writing, 191).

This is not to say that our characters bear no resemblance to persons outside us, but if we look close enough at our most meaningful relationships (the one’s most apt to inspire the creation of our fictional characters), they bear a striking resemblance to aspects of ourselves. The woman you fell in love with it, or the asshole boss you want to punch in the face at least once a week. When you fashion characters after these persons, you’re really writing about yourself.

There’s more to what you call you than what you take yourself to be. The writing process is an activity of this wider field of subjectivity. As such, it’s largely an incursion from the unconscious, not something conscious at all. Fiction opens that door, for writer and reader alike. Whether by sudden fall (through a trap door) or gradual descent (down the basement staircase), fiction takes us to the underworld of our inner life. And a certain change takes place in that journey, for example, the enriching of our perspective and degrees of emotional regulation. In a sense, fiction writing can be a form of therapy, very effective therapy. And perhaps that’s why so many people read fiction.

Third, fiction thrives on ambiguity and open-endedness, and that’s not something characteristic of scholarly writing, the process of argumentation, and criticism. Of course, there’s a place for precision and rigorous reasoning in life, and—contrary to what some of my former Zen teachers have said—criticism too. It’s by no means a bad or counterproductive thing to believe something, to critique, or to reason. Try living without these. That’s just a complete denial of life and the human experience. We can’t escape beliefs, reasoning, and critique, but one can do it with less attachment. And I think that’s what fiction helps cultivate—non-attachment. Perhaps because it sensitizes perspective to its own limitations and thereby opens up further possibilities. And isn’t this true to life? Don’t we live life in the wider space of unknowing, of mystery? We can contently accept our ignorance and learn to play with it, or we can neurotically reject it and live with it dogging us and spinning us out.

This is particularly significant for me since the topics that loom large in my fiction writing are often the same ones I’ve conceptually explored in my philosophical writing. Take the topic of survival of death. I’ve written at length on whether certain paranormal phenomena are evidence for life after death. But if that’s the question I’m asking, I’m working within narrow parameters the question dictates. I’m looking at criteria for evidence, how we assess explanations, and all that. Here I care, for example, whether survival better explains the facts than some rival hypothesis. Was it an actual discarnate spirit or just some psychic imprint left on the environment from some formerly living person? The virtue of an argument might be that it shows one of these explanations is superior, or it might show why it’s difficult to say which, if either, is a better explanation. But this is all about taking up a position of some sort. And it requires being hard nosed and rigorous in reasoning.

By contrast, if I’m writing fiction, I want to leave things as open as possible. I’m dialing-in that aspect of experience. The only positions that matter are those the characters authentically own. And hopefully they don’t agree with each other too often.

Imagine a story in which one character believes a girl is demonically possessed, and another character believes she’s suffering from schizophrenia. As the author, I don’t care which character is correct (hell, maybe they’re both incorrect). I could write that way, but I’m not particularly interested in doing so. I don’t care whether the girl’s really demon possessed, a schizophrenic, or under the influence of pissed off extra-terrestrials. I care about what’s true about the characters, what they believe, and their being true to their own beliefs and acting from their beliefs and intentions.

True, the story might present the skeptic as more reasonable/virtuous than the gullible priest who thinks the girl is possessed. The story might also portray the priest as more reasonable/virtuous than the skeptic. But is that it? I mean, is that the point? Isn’t it rather that the characters are true to themselves? That’s the fertile soil of conflict, and often the path out of it—vital elements of story. And it’s what helps us care about the characters and what happens to them in the story. And maybe, just maybe, this leads the reader into some form of self-realization. After all, the characters of a story are not just a mirror by which the author may see her face more clearly, but it’s also one in which readers may come to see their own face more clearly.

Dreaming with Eyes Wide Open

King has said, “fiction is the truth inside the lie.” Fiction has truth to reveal, but ultimately it’s the truth about the author and reader. And it’s the individual author and individual reader who are the only ones who can know what that truth is. Likewise, the consolation, healing, enjoyment, or satisfaction that a work of fiction brings to life is one the author and reader is uniquely situated to determine for herself. Otherwise put, stories are really, or at least fundamentally, about persons. The persons appear in the pages of the book, and they appear as the eyes behind the book.

As I said at the outset, I’ve spent most of the past twenty years playing conceptual chess and solving logical puzzles. And I’ll probably always do that sort of thing. But I’ve learned that it’s also important to spend a significant amount of time dreaming with my eyes wide open. That’s how King describes the path of fiction, and that seems exactly right.

Michael Sudduth

REVISED 11/29/16

The post Stephen King and the Path of Fiction appeared first on Cup of Nirvana.

May 30, 2016

Empirically Robust Survival Hypotheses

Oxford philosopher H.H. Price (1899-1984), himself sympathetic to life after death, once noted that survivalists – people who believe in life after death – should spend less time collecting evidence for survival and more time examining and clarifying the very hypothesis of survival itself. On the whole, survivalists interested in empirical evidence for survival (specifically, evidence collected from psychical research or parapsychology) have not heeded Price’s admonition. Consequently, the entire field has produced a body of literature that overwhelms in facts but underwhelms in critical analysis and argumentation.

Oxford philosopher H.H. Price (1899-1984), himself sympathetic to life after death, once noted that survivalists – people who believe in life after death – should spend less time collecting evidence for survival and more time examining and clarifying the very hypothesis of survival itself. On the whole, survivalists interested in empirical evidence for survival (specifically, evidence collected from psychical research or parapsychology) have not heeded Price’s admonition. Consequently, the entire field has produced a body of literature that overwhelms in facts but underwhelms in critical analysis and argumentation.

The logical blunders regularly, if not systematically, encountered in the literature are symptomatic of a failure to understand, much less appreciate, the conceptual complexities involved in connecting conjectures and facts. Downstream you find all the poor argumentation that’s called out in a standard critical thinking textbook. This same level of intellectual dopiness has vitiated the initial critiques of my book on survival. These critical reviews have reinforced rather than undercut my pessimistic verdict on the field of survival research. Of course, I’m not alone in this assessment. Philosopher Stephen Braude voiced the same general criticism for years before I began publishing on the topic of survival. And the critique of near-death experiences in the recently published book by John Martin Fischer and Benjamin Mitchell-Yellin provides further evidence for this negative assessment within the community of Anglo-American philosophers.

So let’s be clear here. No, I don’t deny that there’s evidence for survival, but please don’t ask me whether I think there is evidence for life after death. Purple objects are evidence that a being with a purple object fetish created the world. Roughly stated, whenever the predictive consequences of a hypothesis are borne out by experience, you have evidence that your hypothesis is true. Hence, for many hypotheses of survival to which you assign some credence value N, there will be observations such that, after the observation, you ought to assign to your survival hypotheses credence value N+. Yada, yada, yada . . .

Evidence is easy to come by, but this is clearly not what I’m challenging in the survival literature. I’m challenging the entire framework. It’s not that past-life memories (and the entire range of closely-allied phenomena), the messages delivered by mediums, near-death experiences, or whatever else you wish to include are not evidence for survival. It’s that survivalists are for the most part clueless as to how to argue that they are, much less show that the facts under consideration are good evidence for survival. At any rate, they’ve not succeeded in doing this in a way that’s not as trivial as arguing that bananas are evidence that the world was created by a gorilla god with a fetish for fruits with a high glycemic index.

Is there evidence for survival? Wrong question. Or, at any rate, it’s a premature question. That’s what the great H.H. Price understood, but which most survivalists have not understood.

Here’s what you should be asking. First, how many ways can we conceive of life after death? Second, what would we rightly expect as evidence for survival given each of these ways of conceiving of survival?

Now the one thing you should discover in this exercise is that it’s not the mere supposition of survival itself that informs us of what we’d rightly count as evidence that a given survival hypothesis is true. No, it’s the extra-stuff, all the assumptions about survival, assumptions about our memories persisting (or not), our various skills persisting (or not), our personality traits persisting (or not), our being able to interact with the world of the living (or not), and so on. None of these is built into the supposition of survival as such. The most casual rummaging of your imagination, or – the next best thing – the texts of the world’s religious and philosophical traditions, should demonstrate this to everyone’s satisfaction.

There are many ways of conceiving of God, alien civilizations, and invisible gardeners. How I unpack the concept determines what could or would count as evidence for the existence of such entities or corresponding states of affairs. Survival or life after death is no exception to the general rule that determining whether some observational datum O is evidence for some thing X’s existence depends on how X and X’s properties are conceptualized. Only then can we venture with any show of plausibility to say what would be true about X’s (logical and causal) relation to the world.

Nor will it do simply to gather all the evidence that fits one way of thinking about survival and proclaim victory for that concept of survival. This is shameless epistemic chauvinism, and it’s a logical sleight of hand, though obviously not one that I’d put past many survival researchers. After all, that’s why they’re mentally atrophied when it comes to producing a single possible fact that would disconfirm survival. That’s what happens when you merely retrofit facts to your preferred conjecture and engage in poor explanatory reasoning.

When you’re doing that little thought experiment I mentioned above, ask yourself how the world should not look if said notion of survival is true (or not look if survival is true). If you can’t do that, you don’t know how the world should look if said idea of survival is true. Please don’t speak about evidence for survival unless you’re also willing to acknowledge the same kind of evidence for the existence of gods with a purple object or banana fetish, demons masquerading as deceased loved ones, and invisible gardeners who attract yellow jackets. For any observation, there are an infinite number of hypotheses that would lead us to expect that observation. Ask yourself, what facts would count as evidence against the very hypothesis that so easily “accounts” for your privileged facts.

A couple of years ago I asked reincarnation researcher Jim Tucker what fact, if it should turn up, would disconfirm reincarnation. He couldn’t tell me. We need look no further for evidence that the present state of reincarnation research hasn’t advanced beyond the conceptual infancy of Ian Stevenson’s brain child. You can’t tell me how the world should not look if your conjecture is true? I’d suggest that it’s equally impossible to say what would non-trivially confirm your conjecture. If your conjecture fits anything you could possibly observe, you’ve transcended the empirical world. You’re doing metaphysics, writing fiction, or peddling snake oil. None of these should be confused with the empirical stance.

The empirical stance is an unavoidable aspect of everyday life. We know what would count as evidence that so-and-so committed a particular crime, that so-and-so survived a plane crash, that so-and-so is having a heart attack (as opposed to suffering from the flu), or that there’s a snake in one’s garden, that Elvis Presley is alive, that Richard Bachman is Stephen King, or that your car has a defective fuel pump.

In each of the above cases we can say the way should look (and not look) if the conjectures are true. In other words, the conjecture in each case is empirically grounded, or empirically testable if you will. Why? First, because the conjecture is robust; it’s really a bundle of statements (a core hypothesis and auxiliary assumptions). Second, the statements that constitute the bundle, specifically the auxiliary assumptions, are themselves independently testable. The hypothesis is empirically robust.

In the case of survival, nothing can plausibly be said to be evidence for survival without survival being a robust hypothesis, but nothing can plausibly be said to be good evidence for survival unless the robustness of the survival hypothesis is empirical robustness. As I see it, there are many robust survival hypotheses, but I’ve yet to see a single empirically robust one. At present, the auxiliary assumptions that must be enlisted (to do the requisite explanatory work) are either not independently testable or they’re no more independently testable than the auxiliary assumptions that make alternative explanations as good (or bad) as explanations in terms of survival.

– Michael Sudduth

The post Empirically Robust Survival Hypotheses appeared first on Cup of Nirvana.

April 6, 2016

Unphilosophical Fragments

Since the publication of my book on empirical arguments for life after death in November 2015, I’ve been very busy with a range of personal and professional responsibilities. But I thought I’d post a brief message about recent and upcoming events that may be of interest to subscribers, as well as a change of direction in my writing.

about recent and upcoming events that may be of interest to subscribers, as well as a change of direction in my writing.

First, on Friday April 8, I will appear on The Q.Psience Project (www.kgraradio.com) at 6:00pm-8:00pm (pacific standard time). Host Jill Hanson and I will discuss my recent book on arguments for life after death, as well as the future of empirical research into the question of survival. I encourage subscribers to listen in.

Second, I’ve written one paper related to my book that will appear in the Journal of Scientific Exploration this summer, and I’ll be writing responses to some reviewers of my book as we move into the summer. I’ve also committed to writing an entry on “defeaters” for the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which I suppose will appear near the end of the year.

During spring break in March I gave a talk on near-death experiences at the University of Portland. Dr. Andrew Eshleman was kind enough to invite me up north to give a talk to his philosophy of religion class, a thoroughly enjoyable experience. This was my first visit to Portland, and also the first time I read Stephen King in a philosophy class. “Afterlife” (in Stephen King’s Bazaar of Bad Dreams is a whimsical and thought-provoking short story on near-death experiences and reincarnation.

During spring break in March I gave a talk on near-death experiences at the University of Portland. Dr. Andrew Eshleman was kind enough to invite me up north to give a talk to his philosophy of religion class, a thoroughly enjoyable experience. This was my first visit to Portland, and also the first time I read Stephen King in a philosophy class. “Afterlife” (in Stephen King’s Bazaar of Bad Dreams is a whimsical and thought-provoking short story on near-death experiences and reincarnation.

Finally, for a number of years I’ve wanted to write more popular books on topics (philosophical, religious, and psychological) that interest me. That’s something I’ve broached in my blog, which has allowed me to express a broader range of my writing, from more analytical/scholarly pieces to contemplative and poetic works. I still have an interest in writing “scholarly” works (and will do so), but at age 50 it’s time for a change in direction. So I’m moving into more popular publishing markets.

For me, writing must be something more than a job to keep one’s job and beef up one’s CV. In the end, what really matters is whether my writing has honestly expressed life as I’m living it, and whether it’s helped bring other people back to life.

While I’m interested in writing a popular book on survival (in the near future), at present I’m experiencing a revival of my interest in fiction, an interest that goes back to my teenage years. I’m presently writing a novella (now halfway complete) and a novel (I hope to finish this summer). Both involve journeys to the underworld of the human psyche, and each is inspired by my own confrontation with the darker side of experience, which for me has always been the more profound source of light.

“Good writing, good stories, are the imagination’s firing pin, and the purpose of the imagination I believe is to offer a solace and shelter from situations and life passages which would otherwise prove unendurable.” – Stephen King

The post Unphilosophical Fragments appeared first on Cup of Nirvana.

February 6, 2016

Beauty of the World

All the beauty of the world is contained in the grain of sand you hold in your hand and blow into the wind.

All the beauty of the world is contained in the grain of sand you hold in your hand and blow into the wind.

All the beauty of the world is contained in the breath that passes through your lips and merges into the wind.

All the beauty of the world is contained in the fragrance of the ocean breeze, into which your longings disappear.

All the beauty of the world is contained in the taste of an almond, which arises for but a moment and dissolves into the inner night from which it was born.

All the beauty of the world is contained in the cracks of your face, carved by your pain and filled with the tears of your regrets.

All the beauty of the world is contained in the sadness you squeeze from your heart and sacrifice to the earth.

Here you are, at ocean’s edge as the sun sets again. You’re still running, yet still waiting. You’re still hoping, yet still doubting. You’re still longing for but have yet to touch the flower of tomorrow. So also the joy you conceived yesterday remains unborn in the shimmering haze of your unending dream.

Watch the cat chasing mice. Observe the mouse chasing after cheese. Watch your desire chasing itself, hands grasping at the wind.

All of the beauty of the world is found now and nowhere else but here. Where else could you be but here and now? What you seek is neither yesterday nor tomorrow, but a path back to now.

Awaken to the intimate space that surrounds you, in which you were born, live, and shall pass away. Breathe and feel its kiss upon your lips. Fall into the tender arms of death, and let the Great Mother, who has conceived you, give you birth again.

Michael Sudduth

50th Blog

The post Beauty of the World appeared first on Cup of Nirvana.

February 3, 2016

Rivas Redux

Last month I published a response to Titus Rivas’s review of my recently published book on survival. Subsequent to my response, Rivas modified and expanded his original review. Actually, he’s published three separate pieces discussing his original review and my response: his Short Review (revised with corrections and a postscript), a response to my response, and a supplemental piece with selected quotations from my book as illustrations of my alleged errors.

Last month I published a response to Titus Rivas’s review of my recently published book on survival. Subsequent to my response, Rivas modified and expanded his original review. Actually, he’s published three separate pieces discussing his original review and my response: his Short Review (revised with corrections and a postscript), a response to my response, and a supplemental piece with selected quotations from my book as illustrations of my alleged errors.

While I appreciate that Rivas has acknowledged his misrepresentation of both my religious orientation and earlier book on natural theology, I’m afraid that the more serious issues relevant to the cogency of my book’s main argument have gone unaddressed. Indeed, his subsequent responses actually amplify the problems that vitiate his original review. Most generally stated, these are three. First, Rivas has failed to demonstrate an adequate understanding of my central argument. Second, he’s failed to show how his various points undermine or otherwise challenge my central argument. Third, despite my providing clearly stated arguments against the three objections presented in his original review, Rivas proclaims dialectical victory without offering a single counter-argument against any of my reasoned criticisms.

Does Rivas understand the main argument of my book? No, and for all the reasons canvassed in my initial response. His insistence that he understands my argument is baffling, especially since (a) he’s provided no evidence in support of this and (b) I’ve provided very clear reasons that demonstrate the contrary. Of course, there’s a very easy solution here. Rivas can succinctly state my argument and dial in specifically how it’s defective. But Rivas hasn’t done this. This was a crucial problem in his original review, and it’s exacerbated by his subsequent failure to critically engage any of the reasons I presented for supposing that his understanding of my argument is defective. Instead, he’s opted to generate a very dramatic and emotionally charged defense, constructed almost exclusively out of question begging assertions, protracted ad hominem digressions, and an assortment of red herrings.

Let me provide some illustrations.

In response to the reasons I offered for supposing that Rivas doesn’t understand my argument, he writes, “It seems very difficult for Sudduth to grasp the difference between rejecting his analysis and misunderstanding it, as if anyone who does not agree with him must be dumb, denying death, or indolent, or a combination of these” (“Comments on a Response”). The distinction between rejecting my analysis and misunderstanding it is actually very easy to grasp, just as easy as asserting without evidence – as Rivas does – that the distinction is difficult for me to grasp. The problem here is that Rivas is offering a response that assumes that he understands my argument. But that’s precisely what’s in question, and it’s what I’ve argued is false. He’s simply begging the question against my argument. A proper response at this juncture would be to address the reasons I presented that challenge the accuracy of his interpretation of my argument. Rivas hasn’t done this.

As I explained in my original blog response, the failure to state my argument is not without negative consequence for Rivas. It’s counterproductive to his obvious interest in raising relevant objections and defending the integrity of his critical review. However, without doing the proper expository work, he’s unable to show, for example, that my arguments are guilty of taking onboard the implausible assumptions he attributes to them. He’s also unable to show that his specific claims about the ostensible evidence for survival, even if correct, are relevant to my argument, or how exactly his claims are relevant. So Rivas has disabled his own critique.

Another illustration. In his response, Rivas continues to raise the specter of the motivational aspect of certain cases of the reincarnation type and the alleged “implausibility” of the assumptions that must be enlisted by the living-agent psychic functioning hypothesis to accommodate this feature of the cases. In other words, appeals to living-agent psi, if they are to accommodate some crucial strands of data, can only do so at the cost of a significant loss of plausibility. This point is presented as a criticism of my argument. OK. But this criticism needs to be dialed into my argument in some intelligible manner. To do this requires that Rivas show how his point actually impacts my argument. He’s not done this. Needless to say, a precondition of doing so is that Rivas actually state my argument. He’s also not done this.

In the light of the noted deficiencies, let me make my challenge to Rivas very clear. He should state my argument (ideally in standardized form – with the premises and conclusion clearly stated) and then show by way of a clear counter-argument how his point concerning “motivation” refutes my argument. I ask that he be as specific as possible. Does he think his point is evidence against a premise in my argument? If so, which one? He should state it. Or does he think that adding his point to the premises of my argument somehow blocks the inference to my stated conclusion? If so, he should show this. In the absence of a counter-argument of this sort, the contention that he’s refuted my argument has a credence index precariously hovering somewhere near zero.

I’d be interested in seeing Rivas meet this very explicit challenge. It would at least clarify what precisely he finds unacceptable about my argument. As it stands, I have no idea what exactly he rejects. It would also be a wonderful way for Rivas to prove that I don’t understand my own argument, which must surely be the case if Rivas actually understands it. After all, I maintain (and the point was broached in my original response to Rivas) that my argument is consistent with the claim that there are some data the living-agent psi hypothesis doesn’t plausibly accommodate. Presumably Rivas thinks my argument involves a denial of this claim or perhaps that my argument is otherwise weakened or compromised if the claim is true, otherwise his claim wouldn’t be a very sensible basis for objecting to my argument. He should show this. Thus far, he’s not done so.

It’s true, of course, that Rivas makes some claims that are apparently incompatible with some of what I claim in my book. For example, he says: “So if we start, as I do, from a substance dualist ontology, we do not even need to make any new assumption, but we can simply build on something that already follows from substance dualism in general” (1/15/16 postscript to “Short Review”). If Rivas intends to say here that the survival hypothesis can have sufficient explanatory power in the absence of the auxiliary assumptions discussed in chapter nine of my book, then his claim contradicts the conclusion I drew from the auxiliary assumption requirement (applied to explanatory survival arguments). But in that case he must show how substance dualism would lead us to expect the data alleged as evidence for survival. Merely denying one of my claims (be it a premise or conclusion) doesn’t constitute a refutation of my argument, especially when there’s substantial argumentation purporting to provide evidence against what Rivas claims. Rivas’s failure to state my argument has prevented him from dialing in his criticism in a way that’s responsive to what I’ve actually argued.

Contrary to Rivas’s unsupported assertion, substance dualism by itself doesn’t lead us to expect any of the relevant data adduced as evidence for survival. Hence, it’s explanatorily vacuous, unless it’s “bulked up” with auxiliary assumptions. But as I explain in chapter nine of my book, there’s a vast range of assumptions from which to choose. Depending on which ones we select, we get at least a dozen different conceivable models of survival consistent with substance dualism but which would not lead us to expect the data alleged as evidence for survival. Unless we can distribute our credence over these auxiliaries in a way that non-trivially favors one narrow band of auxiliary assumptions over the rest, we simply cannot argue that the data are more to expected given survival than some rival hypothesis. Indeed, we cannot say how the world should look if survival is true. If Rivas thinks otherwise, and wishes to offer something more than an assertion, he should probably respond to the arguments in chapter nine of my book. He must either reject the general auxiliary assumption requirement for explanatory reasoning or reject my particular application of it to explanatory survival arguments. There’s no other option. But again, Rivas hasn’t provided a reasoned account of any of this.

What about those three objections to my book featured in his initial review? I explicitly addressed each one of these objections, which – among other things – involved his attributing claims or assumptions to my argument that I contend are not involved in my argument. I had also noted Rivas’s failure to textually justify these false attributions. Yet, despite his lengthy follow-up responses, including an entire blog that purports to respond to my response to his initial review, Rivas manages not to address a single one of my counter-arguments to his three objections. He dismisses my counter-arguments, along with the dialectical responsibility of addressing them, by merely asserting that they’re “less relevant” and “amount to empty sophistry.” Now I’m not opposed to ostentatious claims. I make them myself when the occasion merits. However, I do my best to make sure that they’re little more than a colorful garnish on full plate of argument. It’s unclear why Rivas thinks his own ostentatious claims should go without support, but it certainly provides yet another illustration of his failure to produce an argument when it’s most needed.

And how would a salient argument go at this juncture? If I present reasons for denying Rivas’s claim that my argument relies on a particular assumption, he must show how my argument is saddled with the assumption. (In fact, he should have done this in his original review.) If I correctly note that he’s not provided textual support for views he attributes to me, he should offer that support or explain why it’s not necessary to do so. If I show that he’s unable to properly engage my argument without stating it, he should either state my argument or show why he can properly engage the argument without stating it. What is unproductive, indeed fallacious, is merely to repeat the very points that I’ve argued are false or otherwise ignore reasons offered up for consideration.

Just to clarify, I’m not claiming that Rivas offers no argumentation at all. It’s that he fails to do so when it matters most. And the latter point is important. It would be unreasonable to demand that Rivas provide reasons for every claim he makes, but his commentary is so vitiated by unsupported assertions, on precisely the points for which I’ve provided argument, that neither human fallibility nor global constraints of space and time provide an adequate defense against the charge that Rivas hasn’t met his responsibilities as a critical reviewer, especially as one who purports to be an advocate of civilized and egalitarian debate. This problem is pervasive in his responses.

Rivas also issues me a challenge. “Perhaps Michael Sudduth will one day have the courtesy and courage to publicly reveal his personal stance on survival (agnosticism, personal survival, personal extinction, or whatever), even if it is still only tentative.” Setting aside the utter irrelevance of this to the cogency of the arguments in my book (which is the central issue), Rivas has once again betrayed his culpable ignorance of matters of fact. I have repeatedly discussed my “personal stance” on survival. In fact, I devoted an entire (5,600 word) blog on this topic in August 2015 – Personal Reflections on Life after Death. While I have a large archive of blog entries spanning the past three years, this is one of the several that has been featured on my website for the last eight months. It appears in both the recent blog archive list in the website widget (which is on the right-hand side of every page of my website), and it’s also highlighted in the center of my main page.

Finally, Rivas characterizes my “program” as destructive.

As I said before, I view Sudduth’s program as destructive. This is because he has given his disturbing diagnosis of survival research such an irrefutable formulation that there seems to be no hope the field will ever progress beyond its supposed impasse. Like myself, many readers will want to know how Sudduth could conceptualize his program as anything else than highly negative. What solution does Sudduth plan to offer that would go beyond a draw between (just) LAP and survival (besides LAP)? (“Comments on a Response”)

I’m actually not offering a general “program” of any sort in my book. I’m offering a diagnosis of what’s wrong with classical empirical arguments for survival. I made this clear in my introductory chapter. Nor is my diagnosis, disturbing as it may be, intended as a complete epistemology of belief in survival. I make this clear in the final four paragraphs of my book, as well as in the introductory chapter. Nothing I argue entails that there’s “no hope” for progress. To be sure, my limited scope project in the book is negative and deconstructive. This is trivially true since I’m arguing that the classical arguments are unsuccessful. But it’s fallacious to infer from this that there’s some larger program that should be characterized in like manner. Of course, the cogency of my arguments doesn’t hang on whether the classical arguments can be fixed, successfully reformulated, or whether there’s some light at the end of the tunnel for survivalists. And I’m certainly not obligated to lead survivalists into the light.

Having said this, as I made clear in my book, if the empirical survival debate is to advance, it’s important to wheel away the rubbish that has increasingly cluttered the conversation for the past century. Much of this rubbish has amassed in area of evidence assessment and its interface with explanatory criteria, which is partially why I chose to focus on the logic of survival arguments. Methodologically speaking, this is the first step in the direction of any sensible recontextualization of the project (broadly construed). Moreover, I chose to deploy techniques and modes of analysis that have been successfully used to advance discussion in other areas of philosophy. If survivalists are uncomfortable with these techniques and modes of analysis, they should propose their own. And if they can at least sufficiently wrap their minds around what I have argued, and just sit with the disturbing diagnosis for a bit, the road ahead might be viewed with greater clarity.

I’ve indicated in my book and blog the direction in which we might move for a positive reconstruction. There’s much more to be said on this topic, and I’ve been very clear about my intention to do so. But I’m in no hurry, and I’m content just to see where it all goes. I’m presently enjoying conversations with others working on the topic of survival, including some preliminary discussions on a possible collaborative project. I personally find more satisfaction in the exploration itself than in the results, which must always be limited and tentative in my view. This is why my views on survival have evolved over the last decade. Anyhow, surely survivalists like Rivas who demand a “plan” or “cure” are capable of putting their own hand to the plow. I look forward to seeing what the best of their intellectual acumen and passion produces.

Michael Sudduth

The post Rivas Redux appeared first on Cup of Nirvana.