Roz Savage's Blog, page 16

February 6, 2020

It’s Not The Critic Who Counts: Lessons from Failure While Daring Greatly

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.” – Theodore Roosevelt

You’re probably familiar with this quote. It gets used a lot, which is partly a tribute to its power to inspire, and probably also an indicator of how often human beings fail.

I used it to console myself – well, somewhat – when my first attempt on the Pacific ended in very public and ignominious failure in 2007. I had run into a big storm about 10 days into the voyage, and my boat had been capsizing more than I expected. It was designed to self-right, and had been doing so, but in all that rolling around I’d dinged my head a couple of times, and had lost my sea anchor. The leecloth fixings had also pulled out of the floor of the sleeping cabin, so it was a bit of a mess in there.

But I would have carried on. Unfortunately, the decision was taken away from me when somebody on the periphery of my team decided to take matters into his own hands, despite my weatherman telling him to mind his own business, and he called out the US Coast Guard to tell them I was having difficulties.

If I had wanted to be rescued, I had insurance with a private rescue company called Global Recovery, and my team had been working with them to develop a detailed plan of action, should the need arise. Unfortunately that option was removed from us when the USCG was called out.

Looking a lot more cheerful than I felt, with the crew of the USCG helicopter. L to R: Kevin Winters, Chuck Wolfe, me, Stephen Baxter

Looking a lot more cheerful than I felt, with the crew of the USCG helicopter. L to R: Kevin Winters, Chuck Wolfe, me, Stephen BaxterLong story short, after much back and forth, me not wanting to be rescued, but the very professional members of the USCG not wanting me to die on their watch, I accepted rescue, and ended up in the back of a Coast Guard helicopter feeling completely devastated, and not knowing if I would ever see my boat again.

If you’ve never been airlifted, I don’t recommend it. They couldn’t pick me up from the deck of my boat, as the line from the helicopter has to be earthed into the sea to discharge the static. So I had to jump into the 25-foot waves, dressed in an oversized survival suit, and wallow over to the Coast Guard swimmer – who was probably about as un-thrilled about all this as I was. He then hitched me to the line and the two of us were hauled up into the ‘copter.

Things then went from bad to worse: I’d been right on the edge of the helicopter’s range, so we needed to make landfall as soon as we could, or risk running out of fuel. But just as we were approaching the closest refuelling point at Point Arena, it got socked in with fog. By now we were “fuel critical”, and would have to fly another 15 mins to get to the next viable refuelling point. I don’t know what the technical term is for the stage after “fuel critical”, but whatever it is, it’s not good. Anyhow, as you can tell by the fact that I’m here to write this, we all made it out alive.

The full story, as recounted at the time, is here. This is when I republished the story of the Pacific crossing – for some reason, when we transferred blog posts from my old website to this one, I asked for the events around that time not to be copied over. I guess I was still pretty raw about it, even years after the event. It’s also covered in my book about the Pacific crossing: Stop Drifting Start Rowing.

And the video recorded by the US Coast Guard is still on YouTube.

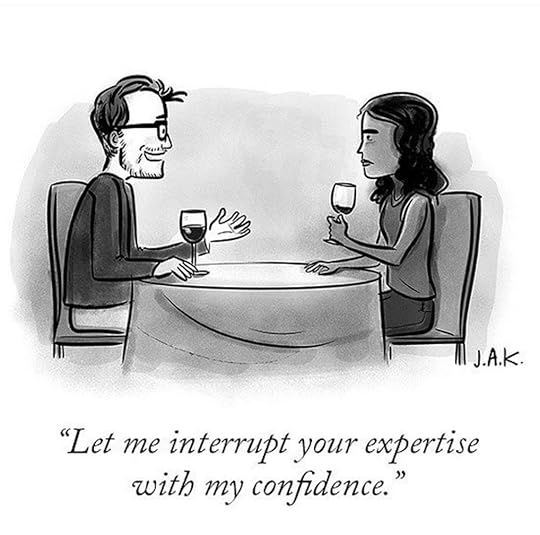

But ah, the best (worst) was yet to come. The online trolling. (I don’t think the word “trolling” had even been invented yet, but that’s definitely what it was.) It felt like every armchair critic on the western seaboard had an opinion. At first it really hurt, to have my intelligence, professionalism, and competence called into question. Naturally, a lot of the abuse used misogynistic terminology. I felt insulted and indignant, on top of the very real practical challenges that I faced to get my boat back before it was either picked up as jetsam, or we lost the signal to its GPS transponder. I also had the strange experience of sitting in a café overhearing a couple of locals discussing the day’s headline news… which was me.

We had to take down the commenting functionality on my website, as it was all getting too nasty. Somebody didn’t take kindly to that either – they knew that my mother had been moderating the comments, and knowing that she would see it, they posted several lines of pure vitriol, including calling her a “F***ing Nazi c**t”. Now you can insult me all you like, but you do NOT say that kind of thing to my mother.

So it was a s***storm. And not fun. But it taught me a lot, which is relevant to anybody who might find themselves on the receiving end of the peanut gallery:

1. People will say any old nonsense, and it’s not personal.

Finally, it was when somebody posted a comment that my female shore manager and I were clearly a lesbian couple that it finally dawned on me how ludicrous the whole thing was. (There’s nothing wrong with being a lesbian couple, but we weren’t.) It was then that I realised that some people will write almost anything, no matter how ungrounded in fact it may be, just because they can.

2. People will be at their meanest when you have reminded them of their own shortcomings.

I discovered I felt sorry for them. What sad, pathetic sadsacks these must be, to have nothing better to do that post ridiculous comments about somebody else’s failure.

In fact, I told myself, the reason they were doing this was because, on some level, it made them feel better about never having tried anything risky themselves. They probably had things they had wanted to do, but they didn’t have the courage. They had talked themselves out of their hopes and dreams because of what might happen. So when they saw me try, and fail, it justified the cowardice that stopped them from even trying. Obviously (cue biting sarcasm) it’s so much better just to sit on your couch in your nice comfy home, throwing insults at someone who is trying to do something out of the ordinary. Because heck, if you put yourself out there, who knows what might happen?

(Wow, finding even as I write this, thirteen years after it happened, it still gets me worked up!)

3. Don’t feed the trolls.

I also learned another valuable lesson: don’t dignify them with a response. It’s SO hard not to. You’re mad at them and you want to set the record straight (which I did do, in a blog post that is no longer on my site, but the USCG were good enough to republish it, with supportive remarks, on their site). But replying to them individually: a) won’t make them change their minds, b) gives them a dignity they don’t deserve, so c) is a complete waste of time.

4. Your actions will speak louder than words.

The best way to respond to them is to pick yourself up, dust yourself off, get back in the saddle (or rowing seat) and next time do it right. Unfortunately, a successful outcome is apparently nowhere near as newsworthy as a dramatic failure. Such is the nature of the media. “If it bleeds, it leads.” But my success the following year – with the added bonus of being able to leave from under the Golden Gate Bridge – left me feeling vindicated.

5. Failure is a sign of success.

Sounds paradoxical, but bear with me. The bolder and more audacious your goal, the more likely it is that you will fail. That’s what comes of being on the edge of what is possible. Humanity has always needed its pioneers, those who are willing to put themselves out there and risk failure – or even death – to expand our collective horizon.

“First they ignore you. Then they laugh at you. Then they attack you. Then you win.” (attributed to Gandhi, although controversial)

In my heart of hearts, I’m proud of what I did. Teddy R. had it totally right. They are “cold and timid souls” who get their kicks out of trying to tear somebody else down. I’m proud of trying, even if on that occasion it didn’t go so well. I failed while daring greatly, and also in the end I knew the triumph of high achievement, and for that I am grateful.

After all, who wants Homer Simpson as a role model?!

Other Stuff:

Last week it was lovely to find how many people had a personal connection with my blog post in some way:

Minette S.’s father was a theatrical and criminal lawyer who helped Hedy Lamarr defend her shoplifting charges.

Howard W. knows Kent Keith, who came up with the Paradoxical Commandments.

And many others had already enjoyed watching Maiden, about the story of Tracy Edwards’ all-female, round-the-world racing crew.

Thanks for all the nice comments!

January 30, 2020

Hedy Lamarr, Bombshell with a Brain

I’ve mostly had my nose firmly to the doctoral grindstone since the start of the year, but last week I took a couple of days to give my nose a rest while I did two speaking engagements in quite contrasting locations – one in Daventry for Platinum Property Partners, and one in Dubai. Apart from the 3-inch heel falling off my keynote-best shoes as I walked across the hotel car park in Daventry, all went well. And it’s amazing what a hotel handyman with a tube of superglue can do at short notice.

I tell you all this for a couple of reasons. First, while confessing that I flew to Dubai (rowing to speaking engagements tends to come with a real risk of missing them altogether), I will also plead forgiveness because my flight – and the flights of all the delegates – were offset by the client company, SITA. While offsetting has its critics, it is certainly better than not offsetting. Thanks to Amber and the rest of the SITA team for making that happen.

(And while we’re on the subject, I will further attempt to salve my conscience by inviting you to take the pledge for a Flight-Free 2020, orchestrated by my fabulous eco-friend Anna Hughes, who I hope will forgive me for my flight-free failure right out of the 2020 gates. Please also think about switching your default search engine on your laptop and phone to Ecosia, who plant a tree for every 45 searches you do. Instructions on how to change your search engine here.)

And second, I wanted to share recommendations for a couple of documentaries I watched during a 30,000 feet movie binge.

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story (not to be confused with the 2019 movie of the same name, which starred Margot Robbie) tells the life story of the Hollywood star, who had already started her acting career in her native Austria, before fleeing the Nazi regime and relocating to the US. It was apparently a source of great frustration to her that people saw her as no more than a beautiful face, blinding them to the brain behind it.

She claimed to have invented frequency hopping, originally so that torpedoes could be remotely controlled without the radio frequencies being jammed by the enemy. It is the same technology that now underpins Bluetooth and Wifi, a multi-trillion dollar industry, but she got little credit and certainly no money for her invention, and died in relative poverty, her face ruined by excessive cosmetic surgery, at the age of 85.

Despite the ups and downs of her life – she was married and divorced six times, her final marriage being to her divorce lawyer, who must have got to know her extremely well over the years – she seems to have had a great ability to roll with the punches. The film ends with a recorded message she left for her son shortly before she died, reciting some lines she had discovered – which seem to me to be very good advice for life and are the main reason why I’m telling you about the film:

People are unreasonable, illogical and self-centred;

Love them anyway.

If you do good people will accuse you of selfish alternative motives;

Do good anyway.

The biggest people with the biggest ideas can be shot down by the smallest people with the smallest minds;

Think big anyway.

What you spend years building may be destroyed overnight;

Build anyway.

Give the world the best you have and you’ll be kicked in the teeth;

Give the world the best you’ve got anyway.

(A quick Ecosia search revealed these lines to come from The Paradoxical Commandments by Dr. Kent M. Keith, with a slightly different version having been found written on the wall in Mother Teresa’s home for children in Calcutta.)

I also watched Maiden, which had been recommended to me by lots of people, but I hadn’t been able to find it on a big screen in the UK. It tells the story of Tracy Edwards, then aged 24, who risked all to skipper the first all-female crew to compete in the Whitbread Round-the-World Race in 1989. They faced hostility, insults, and condescension from other sailors. One journalist called their boat “a tinful of tarts”.

I don’t want to spoil the plot by telling you any more about it – I will just say please, please watch it. If you like underdog stories, you will love this one. It made me cry. A lot. In fact, I’m getting a bit teary as I write this, just thinking about it. And of course I found it extremely relatable, but even if you’ve never braved an ocean in a small boat, do check it out.

The last film I watched was Robin Williams: Come Inside My Mind, and what an amazing mind it was, the mind of an absolute comic genius who was definitely wired differently from most of us. I cried some more.

Despite all the tears, I really enjoyed these documentaries. On the flight out, I’d tried watching Downton Abbey but (please avert your eyes if you’re a diehard Downton fan) I found I just didn’t care about these fictional characters. With notable exceptions, I feel better about myself after watching a true life story than I do after watching a blockbuster. Fact can be so much more extraordinary than fiction.

Other Stuff:

I am starting to put together plans for a speaking tour in Australia/New Zealand for March 2021. Yes, I’m afraid I will be flying again, but if I can pack a lot of engagements into one trip, I feel less guilty about it. If you are interested in having me come and speak to your organisation, please check out my showreel and testimonials and get in touch with my wonderful manager, Miriam Staley.

January 23, 2020

The 7 Ss of Human Perception

Following on from last week’s musings on the nature of reality, I’ve drawn together a short list from various sources (including my own thoughts) on the various ways that we fail to see reality as it really is. Conveniently, there are seven of them, and they all start with S (kind of). Here we go:

Senses

During the Scientific Revolution, many sources of sensory input were discarded or discredited. In its very reductionist way, science wanted to allocate each sense to its own sensory organ, so we ended up with eyes/sight, ears/hearing, nose/smell, tongue/taste, and nerve endings/touch. But most of us have experienced other input that is as real to us as any of these sensations – things like Extra Sensory Perception, telepathy, lucid dreaming, etc. – as if there is other information available to us when we keep our focus wide rather than narrow.

Try this: close your eyes and move as if to touch your nose with your finger, but stop short so your finger is a few millimetres away. Can you sense that it’s there, even though no nerve endings are touching? Most people can. It’s as if you can sense objects coming into your space, even if they’re not yet registering with any of your sensory organs.

Scale

As humans, we perceive things that are relevant to us on our scale, but we’re largely oblivious to things that are too small or too big to matter. Too small: most of us don’t pay much attention to motes of dust. But to a dust mite, a mote appears big, interesting, and delicious. Too big: we’re not good at accurately perceiving large things. I will simply say “Flat Earthers”.

Stale

According to Beau Lotto, by the time our brain has finished processing a new incoming piece of information, it is already out of date. Usually this doesn’t matter, but when things are happening very fast, especially if things are moving rapidly towards us, it’s a problem.

Suitability

An (almost) entirely gratuitous picture of a dog

An (almost) entirely gratuitous picture of a dogDifferent creatures have different ways of perceiving the world, depending on what’s useful to them. Their senses evolve to fit them to their evolutionary niche (or possibly vice versa). Bats can echo-locate (while most humans can’t – with the possibly unique exception of Daniel Kish). Birds have four types of colour-sensitive cones in their eyes (most humans only have three) so they can see ultraviolet light. Dogs smell at least ten thousand times times better than humans (as in, they have a better sense of smell – not that they are greatly more fragrant than us). In fact, human senses are pretty dismal and dull all round when compared with the sensory stars of the animal kingdom.

Safety

As Don Hoffman points out with his FBT theory (see last week’s blog post), fitness beats truth every time. The individual creature that perceives danger sooner (note, sooner, not more accurately) is likely to out-survive and hence out-breed its less danger-aware kinfolk.

Speed

Connected to Safety above, creatures that are more sensitive to fast-moving objects, such as cheetahs or large trucks, have better chances of procreating.

(Ex)Spectations (Sorry, that’s a bit lame, but I’d started with the Ss, so I had to finish…)

We see what we’re expecting to see, and we don’t see what we’re not expecting to see. You might well have seen the gorilla perception test (and if you haven’t, I’ve just ruined it for you – sorry!). You’re less likely to have seen this one, featuring a card trick.

Apparently, we only see sharply a tiny percentage of our overall visual field: if you hold up your thumb at arm’s length, its width is the area you see sharply. We put our attention on the aspect that is most relevant to us, and most of what you see in your peripheral vision is being assumed by your brain, depending on what it expects to be there. We’re getting the gist of a scene rather than an accurate perception.

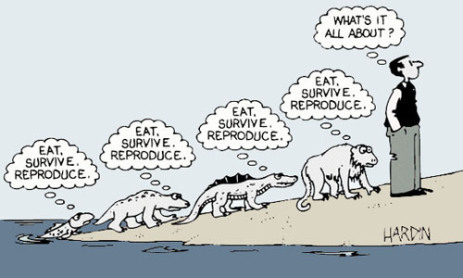

The most important thing to remember in anything related to psychology or neuroscience is that the human brain, for all its wondrous abilities, is a greedy organ, accounting for about twenty percent of our energy consumption, way out of proportion to its two percent of our bodyweight. As we evolved, every single one of those calories had to foraged or hunted, which also required a lot of calories. So the brain developed heuristics, or shortcuts, to save energy. It will do what it needs to do in order to make sure its host (i.e. you) can survive and procreate, while economising as much as it can on energy-expensive processing power.

The most important thing to remember in anything related to psychology or neuroscience is that the human brain, for all its wondrous abilities, is a greedy organ, accounting for about twenty percent of our energy consumption, way out of proportion to its two percent of our bodyweight. As we evolved, every single one of those calories had to foraged or hunted, which also required a lot of calories. So the brain developed heuristics, or shortcuts, to save energy. It will do what it needs to do in order to make sure its host (i.e. you) can survive and procreate, while economising as much as it can on energy-expensive processing power.

So you can look to your brain to keep you safe (which is why it doesn’t like change, nor is it over-keen on critical thinking – both of which come with a significant cognitive overhead), but you can’t count on it to be truthful. (And we haven’t even talked about quantum physics, multi-dimensional reality, or the holographic universe yet – that’s when it all gets seriously mind-blowing.)

So what? – you might very reasonably ask. My perception of reality has served me perfectly well so far, allowing me to function in the world and interact with other people and objects. Why would I bother with all this metaphysical gubbins?

I can only answer from my own experience, which is that learning about this stuff has given me an appreciation that things may not be as they seem, that the world is more complicated – and possibly even more miraculous – than we think. This in turn has helped me to be more humble, less dogmatic. If nothing is as plain as the nose on my face, or as solid as the ground beneath my feet, then maybe there are other things that to me seem intuitively obvious, but are actually dead wrong.

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” – Mark Twain

January 16, 2020

Just How Real Is Reality, Really?

Before I get down to the main business of this blog post, something that would be really appreciated by me would be for you to head over to Medium.com and check out the first article I’ve written for the Better Humans publication. It’s about the infamous obituary exercise that changed my life. If you’re a member of Medium, and you like the article, claps/follows/shares gratefully received!

And fyi, I will always write about things here on my personal blog before I share them with the Medium community, so this is still your best place to keep up with my current thoughts/obsessions.

Now, on to the blog post…

If you want your mind well and truly blown, check out the work of Don Hoffman. He believes – and has mathematical evidence to support his belief – that absolutely nothing we see is what we think it is. In fact, space and time don’t even exist. Yikes!

Don Hoffman

Don Hoffman(TED Talk, his book: The Case Against Reality: How Evolution Hid The Truth From Our Eyes, interview on the After On podcast with Rob Reid)

He claims:

“The problem is not that our perceptions are wrong about this or that detail. It’s that the very language of objects in space and time is simply the wrong language to describe objective reality.”

Before you dismiss him as completely bonkers, give me a moment while I explain more about why I’m open to his point of view.

I’ve written about reality before, and why it might not be as real as we think it is – for example:

On Existence (12th September 2019)

Narratives, Neuroscience, and No Money (4th January 2018) – featuring reviews of Deviate, by Beau Lotto, and Liminal Thinking, by Dave Gray, both on reality

So I was already at the place where I understand three factors that are relevant here:

First, that our brain sits inside the black box of our skull, receiving input from its “peripherals” – sense organs like eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and nerve endings – and it does its best to piece together the world from that information. The brain does not experience reality directly. What it creates is a mental map that enables us to function in the world, but the map is not the territory.

Second, I also already understood (from Liminal Thinking) that the brain is not a neutral recipient of this input data. It has been primed by past experiences to expect the world to function in a particular way. So if the person has had negative experiences – anything from trauma to abuse or even just a specific food making them sick – they will be hyper-vigilant to anything that could be a potential threat in that regard. When we “see” something, the brain is actually drawing heavily on memory to help us interpret what we are “seeing”, so our present is inevitably coloured by our past.

Third, the brain uses a lot of energy. Thinking is, quite literally, hard work, especially when it is what Daniel Kahneman calls “System 2 thinking”. System 1 is our fast, intuitive, emotional thinking, while System 2 is much slower, more cognitive and effortful. You can almost feel whether you’re using System 1 or System 2 – with System 2 you probably stop everything else that you are doing to focus on it, you engage your brain, your brow might furrow, and you kind of turn inward to concentrate. Imagine the difference between calculating 2+2, and calculating 27×33. You can do both in your head, but unless you’re Rain Man, 27×33 will take a lot more effort. So the brain relies heavily on heuristics, or shortcuts, to save on energy. It leaps to the easiest available conclusion.

So that’s what I already knew and agreed with.

But to claim, as Hoffman does, that “Perception is not a window on objective reality. It is an interface that hides objective reality behind a veil of helpful icons” – this was a whole new realm.

He is drawing an analogy with icons on a computer screen. When we stop to think about it, we know that a folder is not a blue rectangle in the top right of our screen. It is not blue, it is not rectangular, and it is not located in the top right. It is a series of 1s and 0s in the circuits of the computer. But if we actually saw the series of 1s and 0s, it wouldn’t be very useful to us. We need a graphical representation of the folder that allows us to open it, move it, or delete it.

Hoffman is saying that our perceived reality is like this: a useful user interface that enables us to interact with reality to do the things we need to do, but it should not be mistaken for reality itself. He calls this the ITP, or Interface Theory of Perception.

To back up this claim, he points to evolutionary biology, which has given rise to his Fitness Beats Truth (FBT) theorem. They have modelled this mathematically, and fitness (meaning the model of reality that enables the organism to “fit in” to its environment) beats truth (meaning an accurate model of reality) every single time. For most of the history of science, we had assumed that an accurate model of reality would obviously be the best one. But apparently not so. As Hoffman pithily puts it: “The truth won’t make you free, it will make you extinct.”

Hoffman’s mission was inspired by the as-yet unresolved “hard problem” of consciousness – science’s quest to explain how a big bunch of molecules like, say, a human, has a subjective experience of its own existence. It’s all very well for Descartes to say, “I think, therefore I am”, but it’s a bit glib, and doesn’t really answer the question. You are, but how are you? What are you? Despite all our huge leaps forward in understanding the world, we still have no idea what makes a thing alive, and conscious of the fact that it is alive.

It is this abject failure to answer this question, or even get close, that made Hoffman suspect that we were buying into the wrong model of reality.

“What false assumption bedevils our efforts to unravel the relation between brain and consciousness? I propose it is this: we see reality as it is… I don’t try to solve the mystery of consciousness. But I do try, in the coming chapters, to dethrone a belief that hinders a solution.”

And he does indeed proceed to inflict great violence on our intuitive perceptions of reality. For example, “ITP makes bold and testable predictions. It predicts that spoons and stars—all objects in space and time—do not exist when unperceived or unobserved.” And it all gets increasingly quantum from there on in.

He isn’t saying that “reality” exists only in our heads:

“There is a world that exists even if I don’t look: solipsism is false. But my perceptions, like observations in quantum theory, don’t disclose that world. They counsel me—imperfectly, but well enough—how to act to be fit. Quantum theory and evolutionary biology, so interpreted, together weave a remarkably consistent story. Quantum theory explains that measurements reveal no objective truths, just consequences for agents of their actions. Evolution tells us why—natural selection shapes the senses to reveal fitness consequences for agents of their actions.”

The implications are startling. As science delves further and further into the tiny realms, was string theory already a thing, or did scientists “create” that domain by looking for it? In the huge realms, are we simply measuring far-flung galaxies, or are we in some way intervening in their existence? As to time:

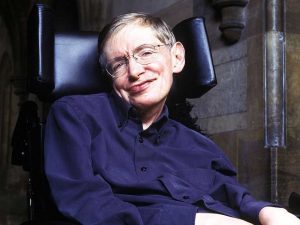

“At least one physicist has argued that the universe has no history apart from observers, that ‘histories of the universe … depend on what is being observed, contrary to the usual idea that the universe has a unique, observer independent history.’ That physicist was Stephen Hawking.”

“At least one physicist has argued that the universe has no history apart from observers, that ‘histories of the universe … depend on what is being observed, contrary to the usual idea that the universe has a unique, observer independent history.’ That physicist was Stephen Hawking.”

… and I hear he knew a thing or two.

I haven’t finished the book yet – I was talking earlier about the brain being energy-hungry, and although Hoffman’s writing is very accessible to the layperson, I still need to lie down in a darkened room for a while after each chapter – but it seems to be leading to some kind of world in which consciousness is the ground out of which all else, including space, time, and the entire universe, arises, rather than the other way around.

If that sounds a bit woo-woo and spiritual to you, maybe it is, but be wary of dismissing it purely for that reason. I haven’t been able to source this quote, but apparently a wise scientist once said words to the effect of:

If that sounds a bit woo-woo and spiritual to you, maybe it is, but be wary of dismissing it purely for that reason. I haven’t been able to source this quote, but apparently a wise scientist once said words to the effect of:

“We think science is achieving so much, but constantly scientists get to a peak only to find a band of ragged monks already sitting there”.

Hope you enjoy my article on Medium.com!

January 9, 2020

Favourite Books of 2019

Happy New Year! I hope you had a wonderful festive season, and that 2020 is being kind to you so far.

As regular readers will know, I love books. I feel like I have a special relationship with them – so often the right book comes along at just the right time. Over the years my progress has been fast-tracked by standing on the shoulders of literary giants.

But there’s always room for improvement. As I was reviewing the highlighted passages from the books I’d read in 2019 (I mostly read e-books on the Kindle app, meaning I can easily review my highlights on the Amazon website – and yes, I know all the awful things about Amazon, but we all have our vices) I was aghast at how much I’d forgotten, even from books that I know seemed really important to me at the time. And it ended up being a huge exercise to review all the 52 books I had read (notice, I don’t say “finished”) last year.

So for 2020 I’m experimenting with a different way. I’ve come up with a reading plan (on an Excel spreadsheet, of course) in which I’ve grouped books by subject. The theory is that by reading several books on the same theme one after another, I will get a more rounded view and create a stronger mental map of the subject. And then if I summarise that group of books, say, in a blog post, I’ll reinforce the learning still further. And I won’t have such a humungous task to catch up at the end of the year.

So, we’ll see how it goes. The other alarming aspect was that it was easy to come up with my 2020 reading list from books I already have in my Kindle library, but haven’t even started yet. The beauty and the peril of e-books is how easy they are to buy, but sadly, for now at least, buying a book is not the same as reading it.

Okay, on to my favourite books of 2019, in no particular order….

At Schumacher College, Devon, in June 2019, (L-R) Satish Kumar, Helena Norberg-Hodge, me

At Schumacher College, Devon, in June 2019, (L-R) Satish Kumar, Helena Norberg-Hodge, meAncient Futures: Learning From Ladakh, by Helena Norberg Hodge

I read this for the pilot Illumination discussion group under the auspices of the Sisters, which was loosely themed on sustainability, but the book touches on so much more. Over the course of many years visiting the remote mountain region of Ladakh in northern India, Helena has learned a lot about their traditional way of life – and how it is now under threat from “development”. The strong social structures that have enabled people to live sustainably, peacefully, and happily for centuries are now being eroded. Income per capita may be rising, but wellbeing is in decline. While on the one hand being a beautiful escape into a simpler and idyllic way of life, the book is also a warning that “progress” isn’t always progress. I also recommend the film based on the book, The Economics of Happiness, available for rent on Vimeo.

The widely acclaimed memoir by the daughter of a fundamentalist Mormon family in Idaho, for whom “home-schooling” meant no schooling at all, but rather child labour in her father’s highly dangerous scrapyard. It’s an inspiring story of courage and determination, as she teaches herself to read and write in order to climb out of the repressive world of her parents.

Men Explain Things To Me: And Other Essays, by Rebecca Solnit

Men Explain Things To Me: And Other Essays, by Rebecca Solnit

Amusing, but also sharply insightful, and occasionally outraging selection of essays that hold a mirror up to the patriarchal society. Rebecca may or may not have invented the word “mansplaining”, but she is certainly its foremost proponent. The essay of the title tells the story of how she and a friend met a man in Aspen who asked her about her work, and she mentioned she had just published a book about Eadweard Muybridge. He immediately leaped in to ask, “And have you heard about the very important Muybridge book that came out this year?” and proceeded to enlighten about her own book, based purely on his reading of the review in the New York Times. Rebecca’s friend had to say three or four times, “That’s her book”, before the words sank in and he realised his faux pas.

I’m not really into self-help books any more, mostly because of the premise that there is something “wrong” with the reader that needs to be “fixed”, but a trusted friend in India recommended this book, and it’s good. Written by the founder of Mindvalley, the personal growth platform, he had me at Law #1: “Transcend the culturescape”. I’m all about questioning the paradigm.

When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times, by Pema Chodron

Wonderful wisdom from a Buddhist nun, this book reminds us that happiness and sorrow are two sides of the same coin, and it’s unrealistic and in fact undesirable to yearn for nonstop happiness, because sadness has so much to teach us. In our culture we deem some emotions “good” and others “bad”, but when we just accept what is, and look for the gift, everything becomes a blessing. This book is balm for the troubled soul. (More about this book in this blog post.)

With Jaimal Yogis in October 2019, Sausalito, California

With Jaimal Yogis in October 2019, Sausalito, CaliforniaSaltwater Buddha: A Surfer’s Quest to Find Zen on the Sea, and All Our Waves are Water: Stumbling Toward Enlightenment and the Perfect Ride, both by Jaimal Yogis

As a fellow seeker for Zen on the sea, I really appreciated these beautifully-written Buddhism-oriented memoirs by surfer Jaimal Yogis. Around the same time I read the fictional Tenzin Norbu mysteries by Gay Hendricks and Tinker Lindsay, with a Buddhist private eye as the occasionally heroic but usually fallible protagonist. For some light, Buddhism-infused reading, this was an unbeatable combination. (More about Saltwater Buddha in this blog post.)

Mary Magdalene Revealed: The First Apostle, Her Feminist Gospel, and the Christianity We Haven’t Tried Yet, by Meggan Watterson

Meggan Watterson is a theologian, but not as we know them. Queer, sweary, and extremely down-to-earth, she takes us on a journey as she investigates the missing gospel of Mary Magdalene (and also those of Philip and Thomas, which didn’t make it into the New Testament for similar reasons). What was so incendiary about these excluded gospels? They said we can all access the divine directly, without the need for priests, bishops, and popes. By rebranding Mary from beloved apostle to prostitute, the ambitious men of the early Christian church scored a double-whammy – they justified leaving her story out of the Bible, while preserving the boys-only bastion of the church hierarchy. A compelling read.

Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War, by Leymah Gbowee

The Nobel Peace Prize winner, Leymah, tells the amazing story of her journey from unmarried mother to founder of the Liberian Mass Action for Peace, using nonviolent protest to bring about the end of the brutal civil war that had wracked her country and claimed the lives of many of her friends and family. A tribute to the power of showing up and doing what is needed, day after day, until the job is done.

Wilding: the Return of Nature to a British Farm, by Isabella Tree

When their estate is no longer viable as a farm, Isabella and her husband turn it back over to nature, which becomes the real star of this book. Nature is marvellous, surprising, and resilient – when we give it a chance. (More about this in a previous blog post.)

Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, by Caroline Criado-Perez

If you live in the UK, you may have heard of Carrie Criado-Perez for her campaign opposing the removal of the only woman to be featured on British bank notes, when the Bank of England planned to replace the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry with Winston Churchill on the £5 note. She succeeded: Jane Austen was installed on the £10 note. Her book is rich with examples, facts and figures on how the “default human” is still male, in all sorts of situations from clinical trials to police body armour to snow clearance. If you don’t have time to read the book, I recommend the podcast in which Carrie is interviewed by former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard – the episode of 20th Sept, 2019, on A Podcast of One’s Own (all sorts of other goodies on there too, including Hillary Clinton, Sandi Toksvig, and Kathy Lette).

If you live in the UK, you may have heard of Carrie Criado-Perez for her campaign opposing the removal of the only woman to be featured on British bank notes, when the Bank of England planned to replace the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry with Winston Churchill on the £5 note. She succeeded: Jane Austen was installed on the £10 note. Her book is rich with examples, facts and figures on how the “default human” is still male, in all sorts of situations from clinical trials to police body armour to snow clearance. If you don’t have time to read the book, I recommend the podcast in which Carrie is interviewed by former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard – the episode of 20th Sept, 2019, on A Podcast of One’s Own (all sorts of other goodies on there too, including Hillary Clinton, Sandi Toksvig, and Kathy Lette).

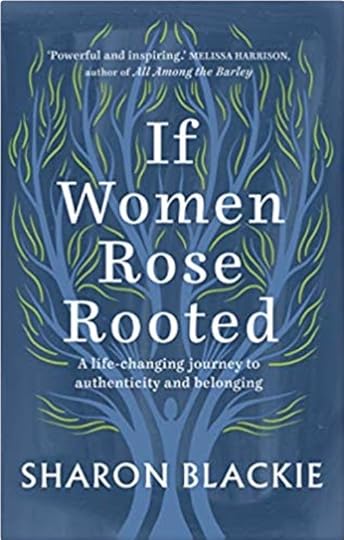

If Women Rose Rooted: A Journey to Authenticity and Belonging , by Sharon Blackie

If I had to choose one favourite book for 2019, this would probably win by a whisker. It resonated very deeply with me, as she describes her escape from the Wasteland of conventional corporate life to the edges of the world, seeking out the remotest parts of the Celtic landscape and re-grounding herself in the land of her forefathers (and, I suppose I should add, foremothers). She weaves together memoir, folklore, and interviews with contemporary women who in various ways are embodying the transition to a more sustainable and grounded way of being. There were so many parallels with my own story that I found myself repeatedly thinking, “Exactly!” and “What she said!” (More in this blog post.)

I hope you might pick at least one of these to try. Let me know how it goes.

And I’ll see how I get on with my new reading plan. Stay tuned!

December 19, 2019

Wishing you a Very Merry Solstice

As I’m currently obsessed with all things yin (as in, yin and yang) I’m loving it that we’re approaching the yinnest time of the year – the winter solstice. This Sunday, here at 51 degrees North, the sun will rise at 8.14am and set at 4.02pm, meaning we have 7 hours and 48 minutes of daylight, and conversely 16 hours and 12 minutes of darkness.

Thankfully not being afflicted with SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) I really enjoy this time of year as a perfect opportunity to hunker down and snuggle in with friends, a good book, and/or a glass of wine as the occasion demands.

It’s also a good time for reflection, and this year I’ve been going all out on an extra-big end-of-decade review – more of a general life audit, really, looking at the various aspects of my life:

Intellectual: what books have I read? what did I take away from them? what have I been writing about in my blogs? what have I learned?

Physical/health: how am I feeling? did I hit my target of average 15,000 steps a day? (yes!) how does my average resting heart rate reflect my health and fitness? (down from 60bpm in the first half of the year to 50bpm in the second!)

Relationships: family? friends? if I’m the average of the 5 people I spend the most time with, who am I?

Financial: how do my finances reflect the value I’m bringing? am I holding true to my “right livelihood” principles?

Home environment: do I feel nourished and safe in my home and its surroundings? is my location supportive of connection with nature? do I find beauty in my place and my space?

Spiritual: how has life encouraged me to grow this year? what have I learned? what books or courses or teachers might help me expand my understanding?

Creative: what space do I make for creativity – with words, with sound, with materials? how do I create balance between left brain activities and right brain activities (aka yang and yin)? what creative endeavours bring me joy?

And of course, these aren’t isolated themes – they are all connected. I step back, evaluate as objectively as I can where I am, and design tweaks to my habits to make sure next year is even better.

By “habits” I mean habits of thought as well as more visible habits – because of course what happens inside (yin) is what shows up on the outside (yang). As within, so without. As above, so below.

So I’ll leave you with that thought as I head off to do the yangiest part of my year-end process, which is to get to email Inbox Zero before I relax for the Christmas break.

I will see you in 2020, which I have the feeling is going to be a very interesting year….!

December 12, 2019

If Women (and Men) Rose Rooted

“We are bleeding at the roots, because we are cut off from the earth and sun and stars, and love is a grinning mockery, because, poor blossom, we plucked it from its stem on the tree of Life, and expected it to keep on blooming in our civilised vase on the table.”

— D.H. Lawrence

Today is general election day in the UK, so having now cast my vote (Green), I am attempting to think about anything but the results, which now lie firmly outside the realm-of-things-I-can-do-something-about.

So I’d like to turn to a book that I read recently, If Women Rose Rooted, that resonated with me very much, written as it was by a fellow refugee from the corporate world who found great solace and meaning in nature as she pursued the Eco-Heroine’s Journey, as she calls it. (If you’re a guy, please don’t stop reading, as I believe this is actually the human journey back to wholeness, and has many similarities with Mac Macartney’s beautiful book, The Children’s Fire, which is also about the urgent need to mend our broken contract with the Earth.)

According to the blurb on her website, “Sharon Blackie leads women on a quest to find their necessary and unique place in the world, drawing inspiration from the wise and powerful females in her native [Celtic] mythology, and guidance from contemporary women who have re-rooted themselves in land and community and taken responsibility for shaping the future.”

According to the blurb on her website, “Sharon Blackie leads women on a quest to find their necessary and unique place in the world, drawing inspiration from the wise and powerful females in her native [Celtic] mythology, and guidance from contemporary women who have re-rooted themselves in land and community and taken responsibility for shaping the future.”

I know and very much admire a couple of these contemporary women: Scilla Elworthy, who has been nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize, and last year wrote an article for my women’s organisation, The Sisters. And Polly Higgins, who passed away too soon earlier this year.

According to Blackie, women have had some bad PR over the last couple of millennia. The book of Genesis did us no favours:

“In this story, the first woman was the cause of all humanity’s sufferings: she brought death to the world, not life. She had the audacity to talk to a serpent. Wanting the knowledge and wisdom which had been denied her by a jealous father-god, she dared to eat the fruit of a tree. Even worse, she shared the fruit of knowledge and wisdom with her man. So that angry and implacable god cast her and her male companion out of paradise, and decreed that women should be subordinate to men for ever afterwards.”

Blackie says that over time this story made her:

“Angry, because it justifies a world in which men still have almost all the real power over the cultural narrative – the stories we tell ourselves about the world, about who and what we are, where we came from and where we’re going – as well as the way we behave as a result of it.”

(If this doesn’t ring true with you, I recommend you take a look at Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, by Carrie Criado-Perez. It’s an eye-opening – and occasionally eye-popping – insight into the many ways that our world is still designed for a “default human” who happens to be male.)

Blackie goes on:

“As I grew older still, I grew angry about other things, too: things that might seem on the surface to have nothing to do with the story of Eve, or the disempowerment of women – but which in fact are profoundly related. The same kinds of acts that are perpetrated against us, against our daughters and our mothers, are perpetrated against the planet: the Earth which gives us life; the Earth with which women have for so long been identified. Our patriarchal, warmongering, growth-and-domination-based culture has caused runaway climate change, the mass extinction of species, and the ongoing destruction of wild and natural landscapes in the unstoppable pursuit of progress.”

(Riane Eisler also points to domination-based culture as the root cause of much that ails the world, in The Chalice and the Blade. In fact, this has been a recurring theme in much of the reading I have done over the last couple of years: when we enact a narrative of domination, it crops up in every aspect of our culture – economic, geopolitical, racial, gender… and ecological.)

To return to If Women Rose Rooted:

“The world which men have made isn’t working. Something needs to change. To change the world, we women need first to change ourselves – and then we need to change the stories we tell about who we are. The stories we’ve been living by for the past few centuries – the stories of male superiority, of progress and growth and domination – don’t serve women and they certainly don’t serve the planet. Stories matter, you see. They’re not just entertainment – stories matter because humans are narrative creatures.

…

“If the foundation stories of our culture show women as weak and inferior, then however much we may rail against it, we will be treated as if we are weak and inferior. Our voices will have no traction. But if the mythology and history of our culture includes women who are wise, women who are powerful and strong, it opens up a space for women to live up to those stories… To be taken seriously, and to have our voices heard.”

Sharon Blackie near her home in Donegal, Ireland

Sharon Blackie near her home in Donegal, IrelandThis is what Blackie goes on to do, very much focusing on “we women need first to change ourselves – and then we need to change the stories we tell about who we are”. So guys, this isn’t having a go at you. We know we all need to work together to create a better future, but we women have some serious work to do to get our own house in order.

“For all my railing against the patriarchy, my own journey wasn’t one which made men the enemy; it was a journey in which men and women could become allies, and the stories which guided me arose from a culture in which both men and women were valued for the different things they brought to the world.”

This isn’t about “leaning in” (a la Cheryl Sandberg) to the masculine world, this is about women’s yin/inner journey, coming up with a better story about what it means to be born female at this time in history.

Part of the work is overcoming the dualistic worldview that has emerged out of Western philosophy over the last 2,000 years, which places us in opposition to ourselves and our environment: mind over matter, men over women, humans over nature. This harks back to the Eastern concepts of yin and yang that I wrote about the other week (in The Yin of Conservation): the Tao is non-dual, in that everything contains the seed of its opposite, and each aspect depends for its existence on what it is not. It is about unity and balance, not separation and domination.

Blackie draws heavily on Celtic mythology, reminding us that we have had powerful female role models within these shores.

“Celtic mythology depicts a society in which women – almost exclusively – held a form of moral and spiritual authority which not only rose directly out of the land itself, but which carried all the weight of the Otherworld… The Celtic divine female in her various incarnations was deeply grounded and rooted in place, indivisible from her distinctive, haunting landscapes.”

She draws a contrast between Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, which focused on the personal transformation of the individual, and the Heroine’s Journey, which she believes is “a journey to understanding how deeply enmeshed we are in the web of life on this planet” and “requires us to step into our own power and take back our ancient, native role as its guardians and protectors.”

I’ll finish with this quote, which is long, but worth reading in its entirety:

Margaret Thatcher was not a great champion of women (!)

Margaret Thatcher was not a great champion of women (!)“When women seek success and ‘equality’ in a male-dominated world, then in order to achieve it we must act like men, play by their rules and, if they deign to allow us, join their societies and institutions. We are judged by masculine criteria for success – and inevitably we fall short, because we are not men. The best we can ever hope to be is not-quite-men, not quite good enough. We live, then, in a culture by the standards of which most women are doomed to fail. But it is easier by far just to go with the system, because this world values women who do: women who stick to the rules, women who do not rock the boat, women who do not push for more. Women who are like men, or women who become what men want them to be. But in becoming what we are not, in colluding with the patriarchy, we are cut off from the source of our own creativity, from the wild mystery and freedom which makes our hearts sing… And in following this path, we prop up and perpetuate the system which destroys us and the planet. In living like this, we embrace the Wasteland… We are caught not only in an industrial wasteland, but in a Wasteland of the heart and the spirit. The Wasteland is not just outside of us, a sickness in the system, in our culture: the Wasteland is in ourselves… The Heroine’s Journey for these times is a journey out of the Wasteland.”

For the record, Sharon Blackie is not anti-men. She has even married a couple of them (not at the same time, obviously). But I would say that she is anti-patriarchy, meaning she is frustrated by systems that advantage men at the expense of women. Her invitation to women is a positive one: to be proud of their gender, and find their voices, while being grounded in deep connection with nature.

I would suggest that the same invitation could equally be extended to men. We ALL need to respect the Earth that we rely on for more than our physical wellbeing – this is about our emotional and spiritual wellbeing too.

December 4, 2019

The Yin of Conservation

I’ve just finished reading Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm, by the gloriously appropriately named Isabella Tree. My thoughts on that intersected with thoughts on listening to my new favourite podcast, Bliss & Grit, and especially their conversation with Jeannie Zandi on “Embodying Yin“, and got me thinking about the currently prevailing approach to conservation.

(There’s a good, quick overview of yin and yang here, but in brief, yin is the feminine/passive principle, while yang is the masculine/active principle in Chinese philosophy.)

Environmental organisations have tended to take a very yang approach, which is unsurprising and forgivable, given that they operate in an economic system where donors want to see a measurable return on their investment in terms of numbers of trees planted, square miles protected, or mating pairs reintroduced into the wild. Give us those lovely yang metrics!

Similar problems appear in the political realm which, in cahoots with the sensationalist media, favours the grand gesture over the “leaving-well-enough-alone”, even though the grand gesture often backfires, tipping over into overkill. I’m sure we can all think of examples where the introduction of non-native species to “solve” one problem has ended up creating a bigger problem. (10 examples of unintended – and undesirable – consequences here!)

In recent years, the increasing sense of desperation has led to ever more yang measures. Implicit in the conceptualisation of a new geological epoch called the Anthropocene, in which human beings are the primary agents of change at a planetary scale, is the notion that we have completed our domination of nature, and every aspect of our ecosystem from now on will have to be micro-managed by humans, despite our extremely imperfect understanding of the systems we are attempting to manage.

For example, it is only in the last few years that the “wood wide web” – the web of mycorrhizal fibres lying under the soil of a forest, distributing nutrients and even a form of information, such as warning of attacking species of insect, between the more conspicuous plants above the surface – has even begun to be understood. This is a relatively straightforward, visible, tangible, measurable aspect of our planet’s complex ecosystem, and yet have only recently started to appreciate its intricacy and intelligence. Meanwhile, geoengineers presume to intervene in one of the most complex and vitally important systems on our planet – the weather.

Hubris didn’t go so well for Icarus

Hubris didn’t go so well for IcarusHubris is the ancient Greek word for the fatal flaw of the powerful, when success tips over into outrageous arrogance, foolish pride, and dangerous overconfidence, leading to the downfall of a group or individual. The ancient Greeks believed that this downfall was preceded by a moral blindness that led the powerful to believe they could do anything they wanted to, free of consequences from either Gods or men. As the yang of expansion swells to its maximum in the yin-yang wheel, the dark seed of its destruction appears at its heart.

Having created a culture, supported by structures, that have led with an increasing inevitability towards severe damage to our environment, we now try to remedy that damage from within the same mindset and the same structures that created it. This appears to be hubristic in the extreme.

What would the yin-yang balanced course be? There is, of course, still a time and a place for urgent and massive action, such as radical decarbonisation, but a useful question would be: “What is the minimum effective response?” in relation to other issues. Sometimes, what is most needed is simply for nature to be left alone to recover.

This may not make for inspiring political vision statements, or gratifying ROI for non-profit donors, and it most certainly will not benefit GDP, but it may be best for nature’s long-term interests. It may run counter to human discomfort once we realise how badly we have messed things up – we have a natural urge to clean up the mess as quickly as we can – but this may not be the appropriate response. For example, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, which happened while I was on the final leg of the Pacific Ocean, was already catastrophic, but was aggravated by BP’s response. Their hasty clean-up operation may have been motivated more by a commercial desire to minimise detectable oil in order to reduce the subsequent fines, than by a conservationist desire to minimise damage, but either way, the results were disastrous. A Georgia Tech study in 2012 determined that the Corexit dispersant made the oil up to 52 times more toxic to the planktonic food chain. A very yang response made a bad situation much worse.

By contrast, I remember vividly the evidence presented by underwater photographer Brian Skerry when he spoke just before I did at the TED Mission Blue conference in the Galapagos in that same year. He talked about the resilience of the ocean, and how life has flourished within marine reserves. He concluded his speech:

“I wanted to finish with this photograph, a picture I made on a very stormy day in New Zealand when I just laid on the bottom amidst a school of fish swirling around me. And I was in a place that had only been protected about 20 years ago. And I talked to divers that had been diving there for many years, and they said that the marine life was better here today than it was in the 1960s. And that’s because it’s been protected, that it has come back. So I think the message is clear. The ocean is, indeed, resilient and tolerant to a point, but we must be good custodians.”

“I wanted to finish with this photograph, a picture I made on a very stormy day in New Zealand when I just laid on the bottom amidst a school of fish swirling around me. And I was in a place that had only been protected about 20 years ago. And I talked to divers that had been diving there for many years, and they said that the marine life was better here today than it was in the 1960s. And that’s because it’s been protected, that it has come back. So I think the message is clear. The ocean is, indeed, resilient and tolerant to a point, but we must be good custodians.”

My interpretation of “custodian” in this context means protecting from harm (yin), rather than proactively intervening (yang).

This yin strategy of less-is-more is nicely captured by Isabella Tree in Wilding.

“Allowing natural processes to happen, and having no predetermined targets to meet, no species or numbers to dictate the plan, is a challenge to conventional thinking. It particularly unsettles scientists who like to test hypotheses, run computer models, tick boxes and fix goals. Rewilding – giving nature the space and opportunity to express itself – is largely a leap of faith. It involves surrendering all preconceptions, and simply sitting back and observing what happens.”

(Anybody who has read the book will know that the author and her husband actually do an enormous amount of work, and not so much sitting back, but as an experiment in conservation their accelerated timeline is tremendously informative.)

“Rewilding Knepp [their estate] is full of surprises, and the unexpected outcomes are changing what we thought we knew about some of our native species’ behaviour and habitats – indeed it is changing the science of ecology. And it is also teaching us something about ourselves, and the hubris that has led us to our current predicament.”

Yang is certainly not a bad thing. It has made our world a better place in so many ways. But we would do well to remember that the classic yin-yang symbol shows a white dot in the black side, and a black dot in the white side, symbolising that each aspect contains the seed of the other. Just as one aspect reaches its zenith, the other aspect is already starting to emerge. According to John Glubb’s theory, our current civilisation has already reached its peak.

Yang is certainly not a bad thing. It has made our world a better place in so many ways. But we would do well to remember that the classic yin-yang symbol shows a white dot in the black side, and a black dot in the white side, symbolising that each aspect contains the seed of the other. Just as one aspect reaches its zenith, the other aspect is already starting to emerge. According to John Glubb’s theory, our current civilisation has already reached its peak.

Could it be that our yang expansion is about to give way to yin contraction? If so, we will need to accept that our future may not be a continuation of our past – and that we will need a new kind of leader to take us into a new kind of reality.

November 28, 2019

What Are We Optimising For?

“What are we optimising for?”

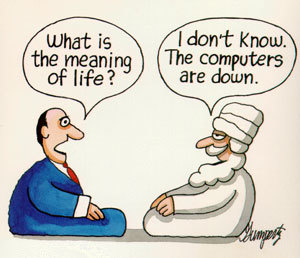

This is the favourite question of my dear friend, Ellen Petry Leanse, when faced with an important decision. Maybe something like: what should my priorities be for 2020? Is this relationship working for me? Or, in a league of its own…. what is the goal of the human enterprise? What are we collectively optimising for?

This came up in relation to last week’s (epically lengthy) blog post on overconsumption. As far as we know, most species don’t have the capacity to question their function here on this Earth. We do. And I feel we haven’t yet arrived at a coherent answer, or certainly not one we can all agree on.

Some very simplistic suggestions… To the religious, we are here to serve God. To the teacher, we’re here to learn. To the athlete, we’re here to win. To the businessman, we’re here to make profit. To the parent, we’re here to raise decent children. To the hedonist, we’re here to party. To the contemplative, we’re here to be enlightened. To the artist, we’re here to create. To many, just surviving may not be their highest aspiration, but it’s what takes up most of their time and energy.

Some very simplistic suggestions… To the religious, we are here to serve God. To the teacher, we’re here to learn. To the athlete, we’re here to win. To the businessman, we’re here to make profit. To the parent, we’re here to raise decent children. To the hedonist, we’re here to party. To the contemplative, we’re here to be enlightened. To the artist, we’re here to create. To many, just surviving may not be their highest aspiration, but it’s what takes up most of their time and energy.

And every philosopher has their own opinion. (My online search for the meaning of human existence yielded this interesting list – although rather depressingly Stephen Fry occupies the #1 spot. We really are in trouble.)

So we may have to agree to disagree on the meaning of human existence. But I hope there are at least three things that we can agree on.

First, that we ought to be thinking about it, and mindfully discussing what it is that we’re optimising for. My concern is that we’re mostly not even making conscious decisions to grow or not to grow, to consume or not to consume. We are mostly defaulting to the status quo, business as usual, while we allow ourselves to be distracted by the loud noises that loom so large just now, of Trump, Brexit, etc., rather than looking at the bigger picture.

(No relation)

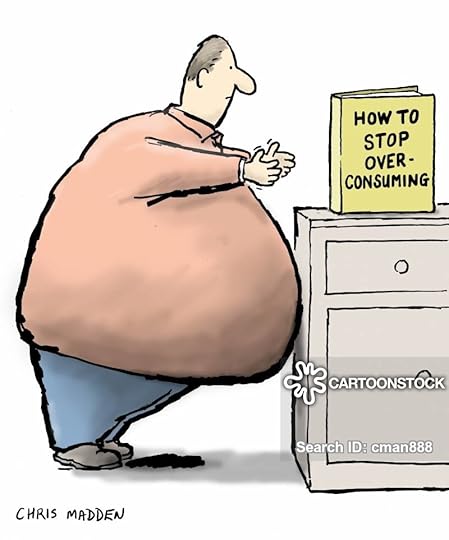

(No relation)Second, that we should each be making up our own minds (and hearts) about it, rather than allowing others (like the advertising industry) to tell us what life is for. I highly recommend The Century of the Self as an eye-opening account of how advertising began – and continues – in order to persuade humans to want more, to pursue our desires rather than our needs… all in service of GDP growth, of course. We have to question the “assumption of consumption” as our route to wellbeing – and ask ourselves if we are using consumption as a second-rate substitute for the things we really want, like love, belonging, a sense of purpose, and self-respect.

(An aside, quoting from Sharon Blackie’s wonderful book, “If Women Rose Rooted”, which I will be reflecting on in a future blog post: “Remember Brave New World? In Aldous Huxley’s ‘utopia’, failure to sufficiently consume was a crime against society. The authorities tried gunning down the ‘Simple Lifers’ who wanted to live differently, but that was neither popular nor effective. And so instead they developed ‘the slower but infinitely surer methods’ of conditioning: immersing people in advertising slogans from infancy. In Huxley’s day, it was still a fiction; today, it’s our reality.”)

And thirdly, assuming that just about everybody reading this blog post is a human (more or less), can we at least agree that human existence should continue?

To be honest, I have my dark days when I’m not so sure, like when I read that the number of wild animals on Earth has halved in the past forty years as humans kill them for food in unsustainable numbers, while simultaneously polluting or destroying their habitats. Or that humans and our livestock make up 96% of all mammal biomass. It doesn’t exactly make me proud to be human.

And yet I’d like to think that there is some purpose to our collective existence here. For all our many faults, humans are still pretty special. I am not a nihilist, one of those people who believes it is all pointless, and I like to think we still have important work to do here – and it would be a shame to frustrate our evolutionary journey through extinction due to our careless abuse of the Earth that sustains us.

And yet I’d like to think that there is some purpose to our collective existence here. For all our many faults, humans are still pretty special. I am not a nihilist, one of those people who believes it is all pointless, and I like to think we still have important work to do here – and it would be a shame to frustrate our evolutionary journey through extinction due to our careless abuse of the Earth that sustains us.

What would that world look like, I wonder, if we optimised for the longevity of the human species? Is that something we could all get behind if we stopped our consumerist lifestyles for long enough to really think about it?

What do you think?

Other Stuff:

Happy Thanksgiving to our American friends!

(speaking of consumption!)

November 21, 2019

Overconsumption – Must, or Madness?

I have been enjoying a robust exchange of ideas with a regular correspondent. We disagree, in some cases vehemently, but we’ve both learned something from the debate. I like to think of it as a Socratic dialogue, where the objective is not to win, but to increase understanding. (And maybe the world could do with more Socratic-acity in our public discourse.) So for the purposes of this article, I shall call my correspondent Socrates (with apologies to Dan Millman/The Peaceful Warrior).

Our lively discussion boils down to a question that lies at the heart of the current economic quandary: do we continue to consume ever more, because this is the way to lift the poor out of poverty and improve life for everybody? Or do we rein back, because our overconsumption is destroying the planet? If you’re a regular reader, you can probably guess which way I’m leaning.

There is a danger, of course, that because this is my blog post, I might skew the argument in favour of my own point of view. So I ran this past Socrates before I published it. So if I have been at all unfair, it is with his permission.

Even though this is an abridged version of our correspondence, this is possibly my longest ever blog post. If you can spare the time, please persevere. If you really can’t spare the time and/or patience, read the first couple of points and then skip to the final conclusions.

This started when Socrates shared the draft of an article he had written, expressing his hope that I would like it. Socrates, I confess, my first impression was that I didn’t like it one little bit. It ran counter to so many of my favourite beliefs (which I suppose is what we like to call our prejudices). But rather than responding with shock and outrage (as is the fashion), I decided to get curious. I’d had enough interaction with Socrates, and we had enough social capital together, that I sensed we could have an interesting exchange about this. So I took a deep breath, set aside my apoplexy, and dived in.

“Hi Socrates. Your article is very interesting, although it also raises a lot of questions in my mind. Maybe you can help me out with these, so I can understand better?” (Blatant playing of the “dumb blonde” card.) I then lifted six quotes from Socrates’s article, and asked for clarification. Socrates, to his eternal credit, was game. “Thank you very much for these questions,” he replied. “I enjoy being challenged.”

It tackles a lot of big questions, so is necessarily incomplete. Please feel free to weigh in!

1. Quote from article: “Our lives have been made better throughout the ages because we have consistently consumed more”. My question: our lives have got better, and we have consumed more, so we undoubtedly have correlation, but do we have causation? Do you have a link to research that establishes this?

Socrates’s reply: I studied some economics at business school. I am by no means an economist, but I understand the basic precepts. It is perhaps so ingrained that I never stopped to think about this point. In economics, a key measure of improvement in living standard is growth in GDP/capita.

See article: What Causes a Country’s Standard of Living to Rise?

GDP/capita growth, in my mind, equates to consuming more. Technically, it is producing more – not consuming more. I sometimes find it hard to make the distinction, because generally a society consumes what it produces. (Sometimes they consume more than they produce.) Therefore, I find myself unable to answer your question satisfactorily. I will research it further.

My (Roz’s) view: The linked article perfectly captures the circularity of the standard argument. It leaps straight from the title, which is about causation, to the first sentence, which is about measurement: “One way to measure the improvement in the living standards of a country is by looking at the growth rate of its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.”

Does rising GDP cause a rising standard of living? Or does it reflect it? Or is there any causal link between GDP and standard of living at all?

As Robert Kennedy famously said in his election speech in 1968, “it [GDP] measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.” Even the creator of GDP, Simon Kuznets, said in 1934 that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income”. And see this long list of quotes reinforcing the point, from all kinds of folks from Ban Ki-Moon to Angela Merkel to David Cameron.

Clearly, a person earning $70,000 a year is going to have a better quality of life than a person living below the official International Poverty Line of $1.90 per day, which equates to about $700 a year. But according to some research , the correlation breaks down above $75,000, due to hedonic adaptation – essentially meaning that too much is never enough. There again, another study says that to achieve “optimal contentment” we would need to possess $100 million. (Wow, sheesh. Most of us had better get used to “SUB-optimal contentment” then.)

So…. Opinions vary. But some useful questions to ask here might be:

To what extent is wealth a determinant of “better”, and how much is “better” a state of mind? (J. Paul Getty was the richest man in the world, but was also a miserable sod .)

How much “better” can a life be? Is more really always more? Or is there a kind of “terminal happiness”, like terminal velocity, beyond which more money can’t buy you any more happiness?

2. Quote from article: “If we were to reverse our consumption habits, which is not possible, humankind would not flourish”. My question: why is it not possible?

Socrates: This is based on two factors, one data-based and one that is intuitive:

Socrates: This is based on two factors, one data-based and one that is intuitive:

1) Based on the data, 194 nations with an aggregate population of 5.5 billion have a GDP/capita less than the global mean GDP/capita (World Fact Book), i.e. they produce/consume less than the global mean. It is a quick-and-dirty metric, since not everyone in those nations produce/consume the national averages. However, the general point is that most of the world’s population is not enjoying the same standard of living that you and I enjoy. But if there is any such thing as fairness, they most certainly should. And they probably would want to, if they knew what it meant.

2) Based on my own feelings, and of most of the people I know, no one, and I mean no one, wants to consume less. If I were forced to consume less, let’s say, owing to straitened circumstances, I would be less happy that I am now. I know this from experience. My friends and I, to a woman and to a man, always want to consume more. Better cars, better iPhones, more paté fois gras, more Champagne, more better everything. This may sound revolting to many people, but it is our reality. (As per my response to (5) below, I do not advocate consuming abusively, however I do advocate for eliminating want.) I have read your excellent essay about your first ocean crossing, and how you lost all your worldly comforts one by one. It sounds as though it was a revelatory experience for you, but as it was happening, it didn’t sound particularly fun.

Roz: Damn right, it wasn’t fun – at the time. But it was tremendously beneficial in the long run. And also, I was privileged enough to get to choose my “poverty”. Most people aren’t.

I think this really comes down to questions like these:

What do we think we are here for? (fulfilment, happiness, contribution, evolution, etc., or fun, hedonism, acquisition, amassing wealth, etc.)

What is the emotional state we are trying to achieve? (happiness, peace of mind, empowerment, connection, safety, etc.)

Daily we are exposed to advertising messages telling us that we can achieve these states if we buy their product, invest in their savings plan, vote for their party, etc. Are these messages true?

What is the emotional state that we hope to achieve by consuming more? What makes us believe that consuming more will enable us to achieve that emotional state?

If we have spent our lives so far consuming more, aspiring to consume more, and/or working to enable ourselves to consume more, has it worked? Have we achieved the emotional state that we hoped to achieve? Is our consumerism bringing us closer to that emotional state?

There is a book called Happier People, Healthier Planet , which surveys and interviews a lot of people (mostly, but not all European or American) who have chosen to consume less, either as a conscious decision or due to circumstances, and this has brought them greater happiness. However, they were a self-selecting sample of people who identified as “modest consumers”, so we can’t assume that their experiences are universal.

Chris Rose, in How To Win Campaigns , identifies three main groups who have different perspectives (and hence need differently-focused campaigns) – from Wikipedia (the percentages are given for the UK in 2012 – they vary over time, and probably over geographies):

Pioneers (inner-directed) are motivated by self-realisation. Their views are governed by values of collectivism and fairness. In their personal lives they are ambitious, but seek internal fulfilment rather than the esteem of others. (38%)

Prospectors (outer-directed) are driven by the esteem of others. They are motivated by success, status and recognition. They are usually younger and more optimistic. They are often conscious of fashion or image, and tend to be swing voters. (32%)

Settlers (sustenance-driven) are motivated by resources and by fear of perceived threats. They tend to be older, socially conservative and security conscious. They are often pessimistic about the future, and are driven by immediate, local issues affecting them and their family. (30%)

It seems reasonable to guess that pioneers are likely to be less consumerist, prospectors more so. So while a prospector may indeed find happiness in conspicuous consumption, for a pioneer consumption may be neutral or even negative. Daniel Kahneman would draw the distinction between “being happy in your life” (more prospector) versus “being happy about your life” (more pioneer).

Here’s something to bear in mind: According to the American Psychological Association , materialistic values are linked to lower life satisfaction. So for those who identify as materialistic and it’s not making them happy, they might want to rethink their value system.

3. Quote from article: “Life would not get better for anyone if we suddenly consumed less. Nor should we expect the ecology to be magically saved by such behaviour. Life would decidedly get much worse.” My question: In what ways would it get worse? Kate Raworth and Tim Jackson write very convincingly on the planetary boundaries and how we can continue to prosper without a growth in consumption. (They also both have excellent TED Talks.)