Sharon Charde's Blog, page 2

December 5, 2023

THE HOLIDAYS

Here they are again.

I don’t know about you, but for me, the time between Thanksgiving and New Year’s is fraught. It arrives with not only our aspirations for joy and celebration, but also multiple layers of stress, memory, hope, and grief--to say nothing of the work of decorating, tree trimming, present buying, candle lighting, card writing and sending, shopping and feast preparations.

The “full catastrophe,” as Jon Cabot-Zinn would say.

The holidays hold so many expectations for pleasure and satisfaction, when so often the opposites are truer. When I was working as a psychotherapist, it was the busiest time of year for my practice. My clients often tried to measure their own experience against the Hallmark card paradigm, and for so many it came up short, causing anguish, self-questioning, and confusion.

“Why do I not have the kind of family I see on TV, or on the many photo greeting cards I receive?” many ask themselves. The “shoulds” operate in higher gear than in the rest of the year; the pressure ramps up to meet both real and imagined demands, of ourselves and of the others in our lives.

My mother always insisted on happiness at holiday time, especially at Christmas. I was never sure whether or not hers was real or forced, but in any case, the expectation was that my sisters and our families would all follow suit, even in the years following our son’s death.

That was hard.

One of the best Christmases I remember was the one a few weeks after Geoffrey was born. We were living in a small apartment in Philadelphia, where my husband John was a medical student at University of Pennsylvania. For two reasons, we could not travel to our parents’ homes as we had always done, bundling up to drive north in our heatless VW Beetle. I’d been diagnosed with viral pericarditis, a more serious disease than I then realized, and was told by a compassionate physician to stay home and rest instead of being hospitalized. And there was a giant snowstorm a few days before Christmas, making travel impossible.

John had a several-week vacation, which allowed him to be fully present and take care of all of us. With what delight I remember seeing he and year-and-a-half-old Matthew walking amidst the waist-high snow to get a $3 tree, small and already shedding needles, and their excitement in dragging it up the stairs to our second-floor apartment. My mother sent some ornaments, and a bolt of red felt from which I cut out stockings, stitched together with green yarn, weaving our names on each. I still hang them every year.

My sisters and parents sent some lovely gifts; we had already known we could only buy one present each for each other. Geoff got little red corduroy booties, and Matthew a plate, bowl, and cup set. John gave me John Updike’s “The Music School,” (which I noticed recently is now a valuable first edition), and I gave my neighbor $10 to buy him Merton’s “Confessions of a Guilty Bystander.” John cooked a goose, and our downstairs neighbors brought up dessert, carols playing on our record player.

It was perfect. There was such delight and warmth as our new young family celebrated its first Christmas together. We had each other, and that was all that mattered. No other Christmas since then has held such simple joy.

We had Jewish neighbors upstairs from us in the third-floor apartment, and I became close friends with Sandy, the wife of another med school student. Growing up in a Catholic world, I’d not known any Jews and was eager to learn about their customs and beliefs. Hard to believe, I know, but it was the first I learned of Hanukkah. Since then, my world has been deeply enriched with many more Jewish friends and how I ache for them especially during the current holiday season. while war is raging in Israel and Gaza. What could they be celebrating, with so much terrifying antisemitism going on, and all that has happened since October 7?

And as I read of the increasing deaths in Gaza, now close to 15,000 I think, I feel the horror that many of us must. It’s hard to feel celebratory, seeing all those terrified bloodied children, the heaps of dead bodies, the knowledge that now the Gazans in the south have nowhere to go to escape the bombing, that Israeli families are traumatized and frightened.

There is so much suffering in the world right now.

I considered not sending cards and my annual letter at all this year, given the world situation and my anguish over it, but I love this way to reach out to all our friends., and connection seems more important than ever. It’s what we should do in every small way we can, a bulwark against the despair and pain that can threaten to overtake us. But when I searched for a message to put on this year’s holiday card, nothing seemed right. Not even the anodyne “Season’s Greetings,” certainly not “Merry Christmas.”

I settled on one word, “Peace.”

And that is my wish for all of you. It is a tall order, maybe even impossible, knowing that many of you have your own issues with aging, poor health, family problems, and agony over the Mideast conflict, but aspiration can perhaps move us closer to finding it in our lives.

May we all have the strength to bear what we must, to find pockets of peace amidst the holiday noise, and share that peace with those around us.

**************

Thank you so much for all for the amazing responses I received to “Radical Empathy,” possibly more than I’ve received for any other post. There are so many opportunities to continue trying to embrace it during the current and continuing nightmares in Ukraine and the Middle East as well as in our country. I continue to try and hope you will too.

October 23, 2023

RADICAL EMPATHY

This week one of my oldest and dearest friends has embarked on an incredibly courageous journey, called VSED (voluntarily stopping eating and drinking) as she has rapidly increasing Alzheimer’s disease, saw what it did to her father and her as she cared for him, and did not want that for her family or herself.

We are in frequent touch with her husband only by email, as they live in a midwestern state and easy visiting is not possible. I had chosen my response by writing her a personal note, sending stones from the beach and recalling memories of our long friendship. However, my husband, struggling with what his acknowledgement to this achingly difficult situation could be, wanted to fly out for a few days and see them. I’d ventured that I thought that wasn’t a good idea, worrying that it would be intrusive, that the family needed intimacy at this time.

But it seemed important to find a way to more clearly define my position, for him as well as myself.

A few years ago, I’d read Isabel Wilkerson’s excellent book, “Caste,” about the hidden system of social order in our country, its rigid hierarchy of human rankings and how it has shaped so much of our history and present. I was taken with her description of a term I’d never heard before, ‘radical empathy,’ a possible way to begin overcoming that relentless and cruel paradigm.

I went back to look up her definition.

Radical empathy…means putting in the work to educate oneself and to listen with a humble heart to understand another’s experience from their perspective, not as we imagine we would feel. Radical empathy is not about you and what you think you would do in a situation you have never been in and perhaps never will. It is the kindred connection from a place of deep knowing that opens your spirit to the pain of another as they perceive it.

“We need radical empathy,” I told him. “To make the right decision, we need to try to feel what it’s like to be where they are, who they are, rather than think about our own needs.”

But how?

I typed ‘VSED’ into the Google search box, and up came an hour-long video with realistic descriptions of what happens to a person when they choose VSED, the many misconceptions around it, and how peaceful and meaningful it can be.

We watched, rapt. It was the help we both needed. Many pictures, email and tears have followed, and the visiting will be saved for later, when our bereaved friend will need comfort after the long ravages this horrible disease has visited on him, his wife, and all their family.

So why am I telling this very personal story now?

Because I believe we are all in great need of radical empathy, given the horrific events in Gaza and Israel of this past week. And because I thought it a possible way to step into the tangled anguish of the individuals involved in those events.

As hard as it is.

We see the pictures of bloodied children, shattered cities, human suffering vaster than we can imagine. We hear of demonstrations, passionate rage on both sides, justifications, calls for revenge, and political arguments. And then add to the poisonous mix the polarization in our Congress, grown men acting like children when we need thoughtful, caring leadership, and yes, radical empathy.

One human life is not worth more than another’s. Let’s not just watch, read, despair, turn away. Let’s work at getting into the skins of Palestinians and Israelis. Perhaps it’s too much to ask right now to do the same for Hamas and Hezbollah, but I always think, each one of these soldiers, these terrorists, was once a baby, a child with hopes and dreams. Perhaps growing up in impoverished circumstances, suffering constant rejection, not having enough to eat or any schooling, has shaped their souls. They each believe fiercely in the rightness of their cause.

As Wilkerson says, those of us who have hit the caste lottery (and that is me and so many of you) “are not in a position to tell a person who has suffered under the tyranny of caste what is offensive or hurtful or demeaning to those at the bottom.”

I do get what a gigantic order this is. I do get the complexity, the injustice, the monstrous barbaric slaughter and its terrifying impact. But I also get that until we can get closer to achieving that connection with the humanity of “the other,” we are doomed.

What is happening now in the world is bigger than us; we can do little to affect it. Yes, we can give money to causes that help and we need to, we can bear witness and weep for the pain we see in the news, but I suggest that what we can do is to reflect on some of these thoughts—not agree—just reflect—and turn to our smaller worlds, finding ways we can reach out to our fellow humans with compassion and kindness, trying out radical empathy as we turn our focus to what the hurt is in their lives rather than our own.

Let it become a practice.

Right now, there is so much suffering. All of us know someone who is burdened, frightened, struggling. Reach out. Think how the world could change, one act of radical empathy at a time.

If ever there was a time that called us to be our best selves, it is now.

******************

The book is “Caste,” by Isabel Wilkerson, well worth a read.

Also, check out this op-ed by David Brooks in the NYT Sunday, October 22: The Essential Skills for Being Human

I am sending much love in this tragic time.

September 18, 2023

COMING HOME

This is such a resonant phrase; I often give it to my writing groups as a prompt. It engenders an immediate and often visceral response, and usually a juicy piece of writing.

There are so many kinds of coming home. There’s the actual act of arriving at the dwelling in which you live. Feeling the comfort of your own bed, after a long trip, or just a movie or dinner out. Opening the refrigerator with its motley collection of leftover pasta, five kinds of cheese, a fuzzy cuke, and door full of half-used condiments--you see the newly mowed grass, the garden you planted yourself, the dog that bounds to you with a euphoria that feels new every time you appear and feel the enfolding of their familiar shelter.

Or, in imagination, to your childhood home, the bedroom you had all to yourself.

Mine was in a ranch house my father had built in a small town in Connecticut, now a big burgeoning city. My sister and I have plans to go and see it after all these years; the owner has let her in once and is willing to again, with me this time. On Zillow, when I look at the ghastly renovations they have made, I notice that the built-ins so popular in the fifties are still there. I had shelves, cupboards, a desk, and bureau, all built in, painted neon pink. Those shelves held my collection of Nancy Drew books, all the Landmark ones, some Madame Alexander dolls on the top shelf. The desk where I drew all my biology assignments, pictures of hummingbirds, amoebae and frogs connected to the bureau where I hid a contraband copy of Bonjour Tristesse under my Carter’s spanky pants.

I still have that blue loose-leaf, all the drawings.

To some of you, walking into a church, attending Mass and communion will feel this way. I was taught as a child that the most perfect of all homecomings was death in the state of grace, so I could go directly to heaven, to sit the lap of God. I’m not sure what I, as a seven-year-old (the age at which we were prepared for communion by confessing a list of sins to a priest in a dark box behind a screen) could possibly have made of that idea.

Then there’s the feeling of belonging to a group, of a coming together with people with like-minded ideas or purpose. Boy or Girl scouts, an athletic team, yes, a church community, a book group, a writing residency, a profession, and especially today, a political party--the support and solace we can have from being affirmed by others who think and believe as we do.

A specific person can feel like home. When I hug my husband of fifty-nine years, I am home in a way I can never be with another. Seeing my son is a homecoming as well, particularly now that he lives so far away. When I go to the cemetery where my younger son is buried, I experience a sense of abode that I wish I didn’t have to have. Being with my sister brings a wash of memory of our long, shared life, all its warts and wonder.

There’s the wow, I get it! that comes from reading a poem or a book filled with ideas that closely resonate with one’s own--connection in the abstract but solace all the same.

When I arrive at Mercy by the Sea at the Connecticut shore in a few weeks and see the women I’ve written with for so many years, our joyful embraces, and the vulnerability we will share in days of writing together I know will feel like falling into a sea of familiar solace. We will be buoyed by each other enough that we can take that experience home to nurture ourselves for days and weeks to come.

But the matchless and most important of arrivals is coming home to oneself. A few weeks ago, I traveled to Barre, Massachusetts, to a place called the Forest Refuge. It’s an offshoot of Insight Meditation Society, a stunning haven of mindfulness practice founded in the seventies by Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzburg, Jack Kornfield, and others who wanted to bring the meditation they’d discovered in India and Burma, to the west.

After my son Geoff died in 1987, I lost my sense of self, who I was and had been. All my moorings came loose, and I had no anchor to swim to. I’d left the church of my childhood years ago and had found no other spiritual haven. Psychology, therapy, the new belief systems I’d embraced in the seventies, provided no relief.

I was homeless.

On one of many trips to Taos to study with Natalie Goldberg, where I discovered my voice in writing but still felt adrift, I met a woman who insisted I come to a meditation retreat in the mountains nearby.

“It will change your life,” she said.

I mightily resisted, but finally acquiesced. And it did change my life, some thirty-three years ago. I clung to the anchor I’d finally found, my own battered soul, embraced in a refuge of kindness and support. Over the years, I’ve “sat” for hundreds of hours, watching my thoughts, feeling my sensations, uncovering stuff I’d not even known was there.

I came to understand self-forgiveness, letting go, impermanence, and how to witness the thoughts and feelings that course through my mind without possessiveness.

And that of course it’s hard-- but that I can always start over in the next moment.

As I drove up the long hill to the Forest Refuge, all of the peace and centering I so needed after the summer of struggle with my husband’s illness, operation, and months of recovery, reached out to welcome me. Each day of the week I was there, the busy world fell away a little more, the silence and total lack of distraction allowed me to be with myself in a way I had not been in a long time.

I’d come home.

**********************

May you all be happy, may you all be peaceful, may you all be safe, may you all be free.

For those of you interested in finding out more about mindfulness practice and IMS, here is the link: imsnews@dharma.org

As always, thanks for reading and for the responses you send me. I so appreciate them.

July 25, 2023

AFTER THE CAMINO

It’s been a pretty intense several months since I last wrote.

April and May included a long-planned trip to Zurich, Switzerland where my son and his wife now live, and a very special pilgrimage hike I’ve wanted to do for a long time, on the Camino de Santiago, the way of Saint James, in Spain.

It was awesome to finally see the Zurich digs--pretty great apartment in a very pleasant city, quite walkable, with a river and a huge lake as enjoyable aquatic offerings. It was fun to be there and Matthew and Hedi were great hosts.

We flew to Madrid to meet the group we’d be hiking with. John seemed particularly exhausted from the fairly short trip and laid down in the hotel room while I went to get some much-needed nourishment. Then began the strange odyssey of an affliction that later put him in the hospital for two weeks and caused a second open-heart surgery.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

He recovered fairly quickly from what we now know (but didn’t then) was a “shower stroke” of the bacteria that were infecting his artificial heart valve, and the next morning we met our cohort of seven, our genius guide German Cruzado, and the amazing Marly Muci who headed the company we traveled with--highly, highly recommended! (marlycamino.com)

A friend recently asked me what made this trip so special, and why was it different from a regular hiking trip?

Well, first of all, it’s an ancient pilgrim way. From the 9th century on when the relics of Saint James, one of the twelve apostles, were discovered, believers came from France, Portugal, and Spain to reach the holy site, now the base of the majestic Cathedral de Santiago Compostella. The path is rich in that history--I could feel it under my feet in the same way I’ve felt the suffering in visits to the Killing Fields in Cambodia and Auschwitz in Poland.

I told him I’d felt deeply joined with everyone we passed on the path, exchanging the greeting Buen Camino, as we walked by each other. There were so many other warm gestures I remember, like the time I was inspecting my hiking partner Lucy’s neck for sunburn and a pilgrim rushed over with sunblock without even being asked. Offers of tissue for bathrooms, euros for café con leche, concern if we were sitting by the side taking a rest, emphasized our shared journeys over and over in a way a “regular” hike never would have.

Such kindness. I hadn’t realized how hungry for it I’d been, until I felt its warmth spilling into every day, every interaction along the way.

It felt so good to be part of something so much bigger than myself.

As our guide German often said, “The Camino provides.” But also, “There is no Camino without pain.”

And that’s where the next part of the path enters my story.

John had been unable to hike given his long Covid symptoms of the last year--that’s why we’d chosen this trip, with the opportunity for those who could not hike, or had a tired or blistered day, to ride in the van. German and Jose Ramon, the van driver, would meet us at check points along the way with snacks, water, encouragement, and one day, a glorious picnic lunch.

John happily rode in the van for the days he could not stay at our accommodations (the one-nighters) and enjoyed the stunning scenery and the company of German and Jose Ramon as well as one of our cohort who had bad blisters and stress fractures--so hard--but was great support for John (thank you, Melissa!).

That is, until the day before the journey’s capstone--the march into Santiago, dinner celebration where we’d receive our certificates, and the Pilgrim’s Mass in the Cathedral, where 8 monks would pull the ropes that swung the giant botafumario. (Catholics, remember the censor swung down the aisle before mass filled with incense?) Only this one was 5 feet tall!

We did all those things, but after we had to take John to a hospital in Santiago city after another event of total body weakness, a second blanking-out episode, and what appeared to be high fever (another one of those “shower strokes”). He, German and I spent 8 hours there, while our cohort patiently waited, then finally went to the accommodation without us for the planned celebration of Jose Ramon and, by their report, a delicious dinner (as most of our meals were).

We left the hospital with no answers, a now well-oriented but still weak husband, and a prescription for an antibiotic, which in hindsight, allowed us to finish the trip.

He was an incredibly good sport, and I was ecstatic to be able to have hiked the whole way. Our group by this time had become family, and a more supportive and caring one would have been hard to come by. Most of us split up planning to reunite the following year in Porto for a longer trek and stay in touch on What’s App and social media.

John and I took the train to Madrid where we spent several wonderful days despite a few more scary but brief events, and many wheelchairs later arrived home after a long plane trip and drive from Newark.

No Camino without pain, remember?

After a visit to our primary care doctor who could find no cause of all these strange symptoms, a few days passed, and he developed a high fever. Despite his considerable resistance, I insisted on a trip to the Sharon Hospital ER where the second part of our Camino journey was to begin.

They quickly diagnosed SBE (subacute bacterial endocarditis) and began a massive infusion of IV antibiotics, which would continue for 7 weeks, done at home via a PICC line. From the ICU he was transferred to Hartford Hospital where he would be for another 9 days, have further tests and, a second open heart surgery to replace the infected artificial valve he’d had inserted exactly 5 years ago.

So it’s been a different kind of journey going forward. Sitting by John’s hospital bed, waiting to hear the results of the surgery, pushing the antibiotics into his line every morning, greeting the nurses and PT practitioners who have been coming to our home weekly, I remind myself that this is all part of the pilgrimage we began in early May, that there is no real “after the Camino,” but that life’s paths of joy and pain are intertwined, and that kindness can bring ease to both.

*******

Though shaken by this perilous journey, we keep moving. John gets a little stronger each day, and my caretaking responsibilities have ceased for the most part. The cushion of kindness that the Camino offered continues to support us both. Thank you, Lucy, Christina, Alicjia, Melissa, Daphne, and Al--and of course, German and Marly. You are the best.

Buen Camino!

May 8, 2023

MAY IS THE CRUELEST MONTH (revisited)

I have just finished a truly extraordinary pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago and cannot wait to write a post or two or three about it, but I am still in Spain and May 9 is coming up so I am reposting this one from a few years ago. I felt Geoff’s spirit with me all the way, carrying me along, pushing me up hills, consoling me as I walked the exhausted last miles of the day, sat with my husband on a most unexpected trip to the Santiago hospital. How lucky am I to continue to not only survive but thrive these 36 years after his death. Buen Camino, my dearest son, wherever you are. I am full of love and gratitude.

I was going to tell you about the great Zoom re-creation of my women’s writing group last Sunday, when seven of us joined for the day to express in words the many feelings and thoughts prompted by poems I shared, but I’m not going to do that.

I debated writing about the powerful virtual mindfulness retreat I sat (in front of my computer) last week, given by renowned meditation teachers Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzburg to 2300 others all over the world. I thought I’d quote Ajahn Chah, Thai meditation master, who said “Anything that is irritating you is your teacher,” thinking it a rich source of reflection for the constant challenge, destabilization and disruption we are all feeling daily—but I just couldn’t get there.

Because, as my son’s beloved teacher said many years ago, introducing me to a group of students at the Trinity College/Rome campus where Geoff spent his junior year abroad, “T. S. Eliot was wrong. The cruelest month is not April, but May, the month Sharon’s son Geoff died from a late night fall from the wall along the Tiber River.”

May has again arrived, and the torment of remembering him, his death, his life, has hijacked my mind and heart.

OUTLIVING HIM

for Geoffrey

His ghost blooms with the lilacs--

nothing takes away May’s missing him,

not the bluebirds his father’s enticed

at last to our backyard

not the ravenous red tulips

or the luminous acres of lawn.

He brings death to the newly born.

It’s not that I forget him in winter.

but winter’s flowers are underground,

sheltered by hard earth--

not the outrageous bursts of spring

I cannot hide from.

His death day sounds its arrival

with dogwood and daffodils

while I, now gray haired and lined,

survive at winter’s edge

unwilling still to outlive him.

(Four Trees Down from Ponte Sisto, 2006, Dallas Community Poets Press)

The anniversary of his death is this Saturday, May 9, the day before Mother’s Day, a day always for me, of tangled emotions. Those of you who have lost people in your life you’ve deeply loved will recognize the memorial surprises of unexpected choking sobs, of darkening moods, of sudden sore throats, chills or headaches that arrive with unerring precision during these anniversary weeks.

It’s been thirty-three years since my son died alone on that dark night in Rome, his death still an unsolved mystery, and the raw chasm of grief it left still surges unannounced. Struggling to find the words for ideas I’d thought to write about this week, deleting everything I began, I realized that his death was my story, that honoring his memory was the only way to get something on the page.

Just this morning, someone I hadn’t seen or spoken to in years asked the question that always comes when someone hears that death has punctured one’s life. It’s such a complex question for me to answer that ten years ago I wrote this poem:

THE STORY

we’re sitting around a table eating lasagna, or walking down a dirt road in Virginia, maybe in a dusty country store crammed with jams and tee shirts and vitamins, or possibly in the back seat of a taxi in New York or a hotel conference room or next to each other on a plane—when the question comes---how many children do you have and I tell the person that I have two but one is dead and see the look I already know I will see---a kind of blanching—a pulling away or maybe back from what they hadn’t wanted to hear and my god I hadn’t wanted to hear it either but now it’s like this unlit candle I carry around never knowing who will have the match and then they say how did your son die—of course you don’t have to say if you don’t want to-- and of course I don’t want to but I do want to and I tell them the story—a little bit—he fell fifty feet from a wall in Rome but then of course they will think it was suicide---which of course is not true--if I don’t tell the rest of the story—how thrilled he was to be a student in Rome—his asthma—the dinner with John—the paparazzi—the branch in his hand—and their eyes are so kind now---they are so full of happiness that their own children are alive—and then they want to know how long ago and I tell them it’s been twenty three years already—he’s been dead longer than he was alive—only twenty one I tell them—although he really wasn’t quite twenty one but it’s easier to say he was and sometimes like today I start to sob surprising myself and causing the other person to back away or hug me and try to comfort me and it doesn’t do any good really because the hole is so big and there’s no way to fill it my god I have tried and tried and will probably try forever and then the conversation turns to what someone’s husband does---what book they are reading—maybe what school their child goes to—because after all we are all trying to tell our stories aren’t we—and I smile and listen and all these candles are burning inside me and even though it’s been so long—you should be over it—I don’t know how to put them out—

New Delta Review, Vol. 27, 2010

I’ve written and written about his death. Six collections of poetry, and now I Am Not A Juvenile Delinquent, my memoir about how I’ve survived it by working as a volunteer poetry teacher at a facility for delinquent girls, despite the fact that that was never my intention in beginning the ten-year program I describe in the upcoming book (Mango Publishing, June 16, 2020). “Writing is a way to transform trauma,” I told the girls—a way to get the inchoate, the unbearable, gone from where it can daily eat you alive, a way to reach and connect with others who’ve suffered in similar ways. I brought them to classrooms, cafes, galleries, The Hotchkiss School, and our yearly poetry festivals, where their passionate, powerful voices reached and affected so many. I hope you’ll all read my book so you can hear those voices too. They are rich and strong and brave. Geoff would have loved them, sensitive creative artist that he was.

For a minute, I let myself think, what, who would he be today, at almost 54? Would he have a wife, children, cousins for my grandsons, be the brother whose death didn’t make Matthew an only child? Would he have followed his creative dreams, or had his tender soul squashed by the harshness of today’s world? But I don’t go far with these thoughts, which always lead to painful dead ends.

Instead, I bring to mind the words I spent a year searching for, to have inscribed on his gravestone, carved deep into rough Westerly granite.

And think not you can direct the course of love

for love, if it finds you worthy, will direct your course.

Khalil Gibran, The Prophet

I draw in afresh the comfort and wisdom of those words, their rightness radiant when I found them at last. They remind me again that love, my love for him, for my living son’s family, for my husband, for the girls, for all of you, and this hurting world we’re inhabiting now, keeps directing the course of my life.

But all those candles are still burning inside of me….

May 6, 2020

March 23, 2023

THE NEXT PLACE

When we were in Switzerland having a lovely ski-mountain lunch with our son and his wife right before the pandemic, I overheard one of their friends refer to “Matthew’s elderly parents” who were here for a visit.

I was 76.

Elderly? Me?

When I hear that word, I envision a frail white-haired woman in a rocker, crocheting doilies or afghans, struggling to get up, a walker or cane nearby. In her closet are matching pumps and pocketbooks from a long-ago time when she could go out into the world, probably hats with veils, flannel nightgowns, serviceable cotton underpants.

But no, it is me, now almost 81, entering that next place. Not exactly the last place, that would be death (unless you believe in reincarnation as I do, though another life sounds exhausting). And despite the fact that I hope it’s not coming anytime soon, I’m getting prepared. I filled out my “Five Wishes” last week and then, inspired, made a list of what I want done with all my stuff, books, jewelry, papers, who might want what, who gets what.

Now on a roll, especially with a worry I might not get the wooden box I want to be buried in next to my son and husband, I called the funeral home my friend’s daughter works at to check. It seems he can get them--phew--and we had a nice chat. He sent me more forms to fill out:

A viewing or wake will be held at: ___________________________________________

My remains shall be embalmed: Y____ N____

There will be an open casket: Y____ N____

The type of casket will be: __________________________________________________

My burial clothing will be: _________________________________________________

The following jewelry should be handled as follows: _____________________________

Well, that’s taken care of.

We sit with friends over glasses of wine, a cheese plate. What do we talk about? Not the last book we’ve read, what our children are doing, a ski trip or even politics--it’s the broken hip, the basal cell carcinoma, our friend’s cancer, or heart surgery, osteoporosis, or most dreaded of all, Alzheimer’s. Then we laugh, catching ourselves, but still move on to the problems of downsizing (which we swear we will never do) or first-floor bedrooms versus chair elevators, long-term care insurance and what it will cover.

In CVS, we browse the greeting card racks for those that say things like, Isn’t it weird being the same age as old people? or We’re not old, we’re just young people who take multivitamins and joint supplements and go to bed early.

And then there’s that pesky thing, memory. Why did I come into this room? What am I looking for when I open the refrigerator? What did I do yesterday? My husband’s gotten smart about this, he writes everything down in a book on his desk, and just to be safe, one in his pocket too.

It’s been hard for me to identify with aging, but I’m determined to face it with as much grace as I can muster. Easy for me to say I know, still upright, devoted to my yoga classes and daily 4–5-mile walks, busy with writing projects, teaching classes, gardening. And my mother lived to see her 100th birthday, my father close to his, so I’m told I’ve “got the genes.”

I have a bevy of (much) younger friends; spending time with them is a balm and a joy--lost in conversation, dancing or taking long walks with them, it’s easy to forget my age.

And I can wear the same clothes from the Gap or Patagonia my grandchildren and their friends wear--jeans, tee shirts, puffy jackets, cute dresses (well maybe not those, after I’ve looked at myself in the dressing room mirror).

Is denial still denial when you’re aware of it?

AARP cover photo March 2023

It’s so different, this new place. What lies ahead, even tomorrow, is a mystery, unclear, uncertain. Maybe it was always this way, but we “elderly” (I put it in quotes as I still resist identifying with such an unattractive word) when younger, were caught up in the lives and needs of our young children, or new romances, or buying a house, a car, a dog, a washing machine. Planning a vacation.

Then the future held promise, or hope--or just was.

I know our ageist society worships youth. Just look in any magazine, or online. Even Eileen Fisher, whose clothes are bought mostly by older women, rarely if ever pictures an older model wearing those expensive sweaters and pants. And on that rare occasion, she always has a perfect figure, a wrinkle-free face. The AARP magazine that comes to our house regularly never has people on the cover who look like the population for whom it is supposedly produced--instead there’s Jane Fonda (whose plastic surgery, workouts, hair dye and Botox injections make her look 40 years younger at least) and a coterie of other celebrities.

What message does that send to the world about aging? That being “elderly” doesn’t change a thing. You can, and should, still look great, even hot. That with a bit of Botox and a sexy outfit, you can pretend that no time at all has passed.

I want to learn to look at aging in a more realistic way. Or at least to face the fact that it is inevitable, this new narrative of our later years. The popular saying--how sick I am of it --age is just a number--is a lie. It is much more than a number. It is wrinkles, weight that’s hard to get rid of, failing eyesight and hearing, shuffling gait, falls, limits of all kinds. The deaths of friends, need to move to smaller spaces, the possibility of illness or yes, death.

It is also, as I said to a younger friend this morning over coffee, true liberation. I can do whatever I want, sleep late, read all day, eat cake for breakfast, lunch and dinner, free to be without a shred of ambition.

There is a richness to aging. The struggles of younger years --to make it, to achieve, to find a partner, to sort through the choices, worrying about which one to make--are over. We’ve worked hard to create our relationships and careers and now can relax some, at least those of us lucky enough to have retirement savings and the stability of a home and children who will be able to care for us when we need it. Though as I write that sentence, I’m immediately stopped by the fact that the world is in such a turbulent state that the very idea of relaxing is hard to fathom.

Still, we need to try. To breathe deeply, to sit with a good book, a good friend, a cup of tea or a glass of wine. To be in this moment, not yesterday or tomorrow, to not want to be other than who we are, comparing our life now to what it was.

Yes, I get that it’s a tall order, a big challenge.

All the more reason to try.

*********************

Here is a link to “Five Wishes”: https://store.fivewishes.org/ShopLocal/en/p/FW-MASTER-000/five-wishes-paper

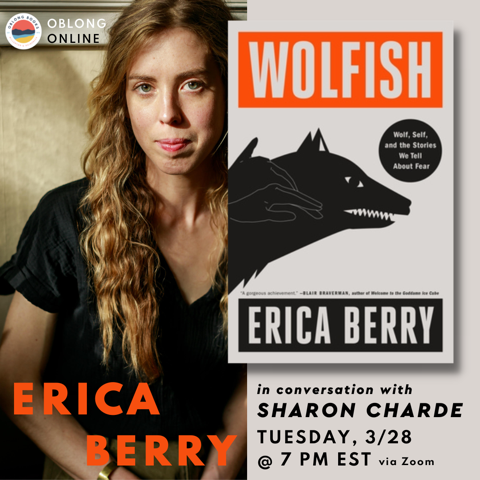

Please register for my conversation with dear friend Erica Berry

https://us06web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_ECEa0oQEQaKy-Kvo_sI3CA

on Tuesday March 28 at Oblong Books in Millerton, about her new and fabulous book, Wolfish, about fear, wolves and so much more, which is getting great reviews. See this one in The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2023/03/wolfish-erica-berry-fear-little-red-riding-hood/673269/

February 13, 2023

FEAR

Gunshots, Covid, polarized politics, Chinese balloons, war and earthquakes, floods and fires, unbridled rage--it’s quite literally in the air these days.

I’ve just finished reading my dear friend Erica Berry’s new book, out this month, called Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear. It’s an amazing work for anyone to have accomplished, but she’s only in her early thirties. Brava, Erica. Brilliant book.

When I was in my early thirties, I was ferrying my two young boys to Little League, Cub Scouts, science camp, hockey games, sleepovers and play dates. Figuring out how to make not-enough dollars stretch, baking bread and listening to Crosby, Stills and Nash, the Beatles, and the Band, fantasizing the writing life I never had.

So, though it is thrilling to be able to embrace my young friend’s success, it evokes a flood of memories and feelings I hadn’t expected, not the least of which is fear, a central theme in her narrative. Though she describes a life mixed with both ample amounts of anxiety and risk-taking, she had been raised as Little Red Riding Hood had, to walk out into the woods unafraid. Adventure and challenge were simply part of her being, part of a family that both sanctioned and encouraged it.

My anxious father was masterful in creating a fearful household. As a toddler he’d returned to this country from Italy during the first world war, with his mother and sister in the hold of a ship. Torpedoes flying, the women screaming, praying rosaries, giving their frightened babies sips of wine from nippled bottles—this was the story he told us about that trip, and what I feel was the beginning of his lifelong fears of just about everything.

Or maybe the fear came too as an unconscious reaction to his wild young manhood --dropping out of school, running with a gang, driving fast, I’m sure drinking too much—he knew what males were capable of. And as an overprotective Italian father in the fifties with daughters—well, boys were absolutely not to be trusted, so no dating allowed. Women and girls were to stay home, under the shielding eyes of men. Added to the patriarchal mores of the times, his fears limited and contained us, his family of females. We couldn’t ride bikes, learning to drive was dangerous (I only got my license at nineteen), there were just so many nos.

Fear was in our DNA.

My mom had grown up with a feisty Polish mother who’d had to cope with two severely disabled sons, losing a husband and his income as a young woman, going to work at several jobs, including at Sikorsky Aircraft during the war, to support her bereaved family. But despite my grandmother’s great courage, storms had always scared her, and she instilled that fear in my mother. So, she (my mother), quaking inside by her telling, held baby me in front of a window when the tempests came, and crooned to me how beautiful was the wildness we beheld.

She pushed me, not the comforting mom that my other friends had. Got my father to pay for the summer camp that changed me into an adventurer, dropped me off at a strange school in seventh grade, let me visit camp friends in New York City and Philadelphia in my teens, told me not to worry when I called terrified from Grand Central Station, that I’d lost twenty dollars, the only money I had.

“I’ll wire you more,” she said. “Don’t worry.”

The mixed messages were both conflict and challenge. My father fought his fears to become a successful businessman though it was a dark day in our household when a deal fell through. My mother inherited her mother’s feistiness, learned to drive our big Packard in her early thirties despite my father’s resistance, fought for me when the nuns at my high school complained that despite having all A’s, I wasn’t working hard enough, challenged the housewife mores of the time by spearheading drives for mental health advances and other causes.

I went away to college in Washington, DC where, though still under the protective eyes of the nuns who taught me, I experienced city living, so different from my sheltered suburban suffocation. With some trepidation, I and my new friends took advantage of everything this exciting city had to offer.

Meeting my now-husband at nineteen and then dating exclusively until marriage at twenty-two, I was insulated from the harrowing, groping encounters I’d had freshman year with dates. We were in love, and in 1964, getting married was what one did. My husband-to- be, a confident oldest male and a first-year med student, was fearless in his assurance that we would be fine, despite having only $350 to our name. To support us, I had a job lined up in a big inner-city school where I’d be making $4,000 a year as a teacher. To get to the job, I had to learn how to drive our stick-shift VW, which I had to master on our honeymoon, accomplished with much grinding of the gears.

Despite his confidence in me, I was terrified.

Answering to a name I’d been assigned only a week earlier, I was a teacher so young the staff confused me with the students. Struggling with the stick shift, the ordeal of finding a parking space near my school, juggling prep for six classes of fifty kids each, I started every day with anxious apprehension as well as the nausea and lightheadedness of a pregnancy I had yet to realize.

We lived in a dicey neighborhood in a second-floor walk-up with no yard, the elderly electrician who came to fix some light fixtures attacked me sexually, there was an attempted break-in while I was grocery shopping, and my school, a la Elizabeth Warren’s experience, let me go at Christmas because I was pregnant and therefore a dangerous influence on the girls in my freshman classes, four of whom were already pregnant.

As I write this, I cannot fathom how I coped. But upon reflection, I think I managed by challenging my fear every day, as my father must have, as my courageous grandmother and gutsy mother did. I knew I had to be there for my baby, and then a second one. But becoming a mother gave me new opportunities for fearfulness—whom of us has not worried about our children’s safety, their illnesses, their well-being, successes, and failures?

Their possible deaths.

The seventies roared in and with them, the welcome invitation to cast off our fears, our captivity, our bras, our imprisonment in the gender roles to we’d been assigned. It was an exciting and liberating time and I thrilled to the new freedoms, though the life I had did not invite much room for them except in my head.

Our move from university housing in Rochester where I’d been buoyed by the support and friendship of other young resident’s wives, flung me into a traditional, WASP-y community the seventies revolution had yet to reach. But for one dear friend my own age with whom I hiked and biked and drank lots of coffee, I was deeply different from all the other wives and women I met in our staid neighborhoods.

For the boys, I rallied, and submersed myself in their activities, was elected to the school board, searched for some more like-minded friends. Geoff’s asthma was a constant worry, but when he started at Hotchkiss, I went back to school to train as a psychotherapist. It was exciting to study psychological afflictions and learn to be useful to those who came to me for help.

Then, both boys were away at college. Geoff longed to go to Rome for his junior year, the perfect place to study his major, art history. When he called to tell me he’d gotten into the program he’d so wanted, I cried. It was 1986, there’d been bombs in the Fiumocino airport, the air in Rome would be toxic for his asthma.

“Mom, why are you crying? This is the happiest day of my life.”

“Because I’m so afraid something will happen to you.”

And something did, the worst of all fears realized. Raw grief consumed me for years; I was sure I would never be the same. And I am not. I think in a way, his death was curative—nothing could ever hold that much fear for me again.

***

Erica and I will be in conversation about her debut book on March 28 at 7:00 on zoom, for the Oblong Bookstore. It’s out on February 21, just a few weeks from now. Here’s what one review had to say about it: A Most Anticipated Book of 2023: Vulture, Salon, Bustle, The Rumpus, The Financial Times, Debutiful, and more!

"Wolfish starts with a single wolf and spirals through nuanced investigations of fear, gender, violence, and story. A GORGEOUS achievement." ―Blair Braverman, author of Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube (And Blair’s book is pretty great too!)

February 12, 2023

ONLY CONNECT (Copy)

FEAR

Gunshots, Covid, polarized politics, Chinese balloons, war and earthquakes, floods and fires, unbridled rage--it’s quite literally in the air these days.

I’ve just finished reading my dear friend Erica Berry’s new book, out this month, called Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear. It’s an amazing work for anyone to have accomplished, but she’s only in her early thirties. Brava, Erica. Brilliant book.

When I was in my early thirties, I was ferrying my two young boys to Little League, Cub Scouts, science camp, hockey games, sleepovers and play dates. Figuring out how to make not-enough dollars stretch, baking bread and listening to Crosby, Stills and Nash, the Beatles, and the Band, fantasizing the writing life I never had.

So, though it is thrilling to be able to embrace my young friend’s success, it evokes a flood of memories and feelings I hadn’t expected, not the least of which is fear, a central theme in her narrative. Though she describes a life mixed with both ample amounts of anxiety and risk-taking, she had been raised as Little Red Riding Hood had, to walk out into the woods unafraid. Adventure and challenge were simply part of her being, part of a family that both sanctioned and encouraged it.

My anxious father was masterful in creating a fearful household. As a toddler he’d returned to this country from Italy during the first world war, with his mother and sister in the hold of a ship. Torpedoes flying, the women screaming, praying rosaries, giving their frightened babies sips of wine from nippled bottles—this was the story he told us about that trip, and what I feel was the beginning of his lifelong fears of just about everything.

Or maybe the fear came too as an unconscious reaction to his wild young manhood --dropping out of school, running with a gang, driving fast, I’m sure drinking too much—he knew what males were capable of. And as an overprotective Italian father in the fifties with daughters—well, boys were absolutely not to be trusted, so no dating allowed. Women and girls were to stay home, under the shielding eyes of men. Added to the patriarchal mores of the times, his fears limited and contained us, his family of females. We couldn’t ride bikes, learning to drive was dangerous (I only got my license at nineteen), there were just so many nos.

Fear was in our DNA.

My mom had grown up with a feisty Polish mother who’d had to cope with two severely disabled sons, losing a husband and his income as a young woman, going to work at several jobs, including at Sikorsky Aircraft during the war, to support her bereaved family. But despite my grandmother’s great courage, storms had always scared her, and she instilled that fear in my mother. So, she (my mother), quaking inside by her telling, held baby me in front of a window when the tempests came, and crooned to me how beautiful was the wildness we beheld.

She pushed me, not the comforting mom that my other friends had. Got my father to pay for the summer camp that changed me into an adventurer, dropped me off at a strange school in seventh grade, let me visit camp friends in New York City and Philadelphia in my teens, told me not to worry when I called terrified from Grand Central Station, that I’d lost twenty dollars, the only money I had.

“I’ll wire you more,” she said. “Don’t worry.”

The mixed messages were both conflict and challenge. My father fought his fears to become a successful businessman though it was a dark day in our household when a deal fell through. My mother inherited her mother’s feistiness, learned to drive our big Packard in her early thirties despite my father’s resistance, fought for me when the nuns at my high school complained that despite having all A’s, I wasn’t working hard enough, challenged the housewife mores of the time by spearheading drives for mental health advances and other causes.

I went away to college in Washington, DC where, though still under the protective eyes of the nuns who taught me, I experienced city living, so different from my sheltered suburban suffocation. With some trepidation, I and my new friends took advantage of everything this exciting city had to offer.

Meeting my now-husband at nineteen and then dating exclusively until marriage at twenty-two, I was insulated from the harrowing, groping encounters I’d had freshman year with dates. We were in love, and in 1964, getting married was what one did. My husband-to- be, a confident oldest male and a first-year med student, was fearless in his assurance that we would be fine, despite having only $350 to our name. To support us, I had a job lined up in a big inner-city school where I’d be making $4,000 a year as a teacher. To get to the job, I had to learn how to drive our stick-shift VW, which I had to master on our honeymoon, accomplished with much grinding of the gears.

Despite his confidence in me, I was terrified.

Answering to a name I’d been assigned only a week earlier, I was a teacher so young the staff confused me with the students. Struggling with the stick shift, the ordeal of finding a parking space near my school, juggling prep for six classes of fifty kids each, I started every day with anxious apprehension as well as the nausea and lightheadedness of a pregnancy I had yet to realize.

We lived in a dicey neighborhood in a second-floor walk-up with no yard, the elderly electrician who came to fix some light fixtures attacked me sexually, there was an attempted break-in while I was grocery shopping, and my school, a la Elizabeth Warren’s experience, let me go at Christmas because I was pregnant and therefore a dangerous influence on the girls in my freshman classes, four of whom were already pregnant.

As I write this, I cannot fathom how I coped. But upon reflection, I think I managed by challenging my fear every day, as my father must have, as my courageous grandmother and gutsy mother did. I knew I had to be there for my baby, and then a second one. But becoming a mother gave me new opportunities for fearfulness—whom of us has not worried about our children’s safety, their illnesses, their well-being, successes, and failures?

Their possible deaths.

The seventies roared in and with them, the welcome invitation to cast off our fears, our captivity, our bras, our imprisonment in the gender roles to we’d been assigned. It was an exciting and liberating time and I thrilled to the new freedoms, though the life I had did not invite much room for them except in my head.

Our move from university housing in Rochester where I’d been buoyed by the support and friendship of other young resident’s wives, flung me into a traditional, WASP-y community the seventies revolution had yet to reach. But for one dear friend my own age with whom I hiked and biked and drank lots of coffee, I was deeply different from all the other wives and women I met in our staid neighborhoods.

For the boys, I rallied, and submersed myself in their activities, was elected to the school board, searched for some more like-minded friends. Geoff’s asthma was a constant worry, but when he started at Hotchkiss, I went back to school to train as a psychotherapist. It was exciting to study psychological afflictions and learn to be useful to those who came to me for help.

Then, both boys were away at college. Geoff longed to go to Rome for his junior year, the perfect place to study his major, art history. When he called to tell me he’d gotten into the program he’d so wanted, I cried. It was 1986, there’d been bombs in the Fiumocino airport, the air in Rome would be toxic for his asthma.

“Mom, why are you crying? This is the happiest day of my life.”

“Because I’m so afraid something will happen to you.”

And something did, the worst of all fears realized. Raw grief consumed me for years; I was sure I would never be the same. And I am not. I think in a way, his death was curative—nothing could ever hold that much fear for me again.

***

Erica and I will be in conversation about her debut book on March 28 at 7:00 on zoom, for the Oblong Bookstore. It’s out on February 21, just a few weeks from now. Here’s what one review had to say about it: A Most Anticipated Book of 2023: Vulture, Salon, Bustle, The Rumpus, The Financial Times, Debutiful, and more!

"Wolfish starts with a single wolf and spirals through nuanced investigations of fear, gender, violence, and story. A GORGEOUS achievement." ―Blair Braverman, author of Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube (And Blair’s book is pretty great too!)

January 18, 2023

ONLY CONNECT

“I define connection as the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard, and valued; when they can give and receive without judgment; and when they derive sustenance and strength from the relationship.”

Brené Brown

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately—maybe it’s my age, a time when friendships truly feel like jewels in the hand—maybe because so many friends have been meeting trouble—health, accidents, bad luck, deaths of spouses—and our linkages bring comfort in the face of what cannot be changed.

I’ve been pretty passionate about connection for as long as I can remember. As a child, friends provided a much-needed escape and comfort from the turmoil of my home, where disconnection was the dominant theme.

For five summers, I went to a girl’s camp in the Adirondacks where Brown’s definition of connection defined our everyday experience. We lived in age-related cabins, where cooperation with each other was essential for harmonious living. The camp was divided into two teams, which competed ardently every weekend in swim meets, baseball, games like Pioneers and Indians and Capture the Flag. Our days were filled with activities like tennis, archery, riflery, hiking and canoeing, but to me the absolute best part was campfire, where we all sat nestled into each other, singing beloved camp songs, then out into the crisp night to hold hands around goodnight circle as we sang taps.

Though I attended an all-girls high school and a women’s college, both formative experiences in community and connection, I believe that my camp experience was intrinsic in forming both my entire professional and personal lives. The joy, the energy, the ease of working together for common goals, the healthy competitiveness and deep sharing, life lived mostly in the out-of-doors, but perhaps most of all, the absence of the opposite sex, made for a truly halcyon experience, which I sorely missed as an adult.

So, both out of need and knowledge of their importance, I’ve tried to replicate something of what those early experiences of connection were for me, for others. Working as a therapist in the early eighties, when gender was bursting onto the scene as a long-ignored critical dynamic in family and marital relationships, I introduced groups for women, to nourish connection as both balm and empowerment. Exploring the damage done by years of patriarchy and roles in life and marriage that made women feel “less-than,” often suffering from depression and the overwhelm of juggling childcare, housework and jobs, the groups supported women in a way individual therapy could not.

After Geoff died and I went to New Mexico to study writing practice with Natalie Goldberg, I realized that writing in groups as we did there was astonishing in its capacity to offer connection that was both healing as well as instrumental in developing conscious living, what E.M. Forster meant in Howard’s End when he used the phrase “only connect.” Very progressive for his times, Forster felt that the most important quality in a person was the ability to connect the inner life with the outer life, and that if we do not learn how to do this, our disconnectedness will come around to haunt us.

As both a therapist and a writer, I completely agree. So, I set out to create my women’s writing groups, led now for thirty-four years. I wanted to separate women from their busy lives for a time to join with other women in the most nourishing environment I could create, to foster connection with their inner selves as well as with each other, using writing practice as a tool. For many years we met for weekends on Block Island, as well as weeknights in my office and home, and all-day Sundays. One of the hundreds of participants through the years captures the essence of the group in these words:

Sharon creates an amazingly safe and nurturing environment that enables us all to move toward our true voices. As we write and speak our words, we hear and are heard in a deep way. The process reminds me how to be present as a listener. These retreats are a sanctuary where there is no judgment, just loving witness.

Of course, the larger goal is that of carrying this experience out into the wider world, to both enhance our own lives as well as those around us. I am indebted to all the women whose lives have touched mine and each other’s in this profound way.

******************

I wrote this post in response to a call by the Story Circle Network, a women’s writing organization, to write on the Brown quotation, I couldn’t resist, as I say in the post, as so much of my life has been devoted to what I’ve perceived as this deep need both in myself and in others. Since I was limited to 750 words, I was unable to go into more detail, but as most of you, my readers, know, I carried this circle much further into my years at Touchstone, a residential facility for delinquent girls, where writing in a group like this gave so many young women the same opportunity as groups for women have, and produced some pretty fantastic poetry and prose. https://www.storycircle.org/book_review/i-am-not-a-juvenile-delinquent-how-poetry-changed-a-group-of-at-risk-young-women/

For the new year, I wish you strength and courage to deal with whatever challenges appear in your lives, and hope that you will grasp all the happiness you can find along the way.

Love, Sharon

December 7, 2022

LETTING GO

I’m terrible at it.

And I’m not even sure why I’ve chosen to write about such a challenging subject for this post, especially right before Geoff’s birthday. I can feel the beginnings of the anniversary sadness that always hits me around this time, so close to the holidays, the memories that crash and spill into my heart.

Maybe it’s because “we teach what we most need to learn,” and I need to be reminded for the thousandth time of the Buddhist philosophy’s wisdom I’ve tried to adopt in the years since Geoff died.

That’s when the phrase “letting go” entered my personal lexicon. You must let go of your grief, your mourning, move on, I was repeatedly told.

To me, that meant denying my feelings of grief and loss, living a pretense, projecting that all was well, that I was quite okay, despite tragedy’s destruction of life as I’d known it.

And I didn’t want to, feeling that grief was a connection to my son, that I would be disloyal to him if I surrendered it. I clung to my mourning, wore it like a talisman that daily marked my loss.

Yet I was also mother to another son, and wife to a husband. And not functioning very well in either role. Guilt added to grief, and I was stuck in their gluey morass.

I began to write, about his death, my struggle to accept what was and how it was affecting our family. Those early poems became the first portal into the relief I didn’t know I needed or even wanted. Often, I have described writing as a way to transform the inchoate—the unruly mess of feelings in our guts and hearts—as a way to create a new being, a piece of art, something outside of ourselves.

I have come to understand that’s what letting go is, actually. An embrace of reality, then an acceptance of that reality, coupled with a healthy dose of self-forgiveness. A sure knowledge of impermanence, that everything is always changing, that we have no control.

An invitation to start over, each minute, each hour, each day.

A friend I met at a writing workshop in New Mexico insisted I must attend a meditation retreat. She refused to take no for an answer, insisting it would change my life. So, I listened to her, traveled to Taos, and learned breath and silence on the side of a mountain, with the guidance of wonderful teachers, Sharon Salzburg and Joseph Goldstein.

I was learning how to carry my grief differently.

But integrating these seemingly simple concepts into a life takes time—months, years. And grief is an unruly companion. It has toppled me in surprising moments. Triggers lurk everywhere, especially at this time of year, when everyone is supposed to be happy, when Geoff’s birthday reminds me of all I have lost.

It’s hard not to get caught.

In an email I recently received, I read these words of Alan Watts and laughed—with recognition of all the bones I’ve broken in the past.

“When a cat falls out of a tree, it lets go of itself, becomes completely relaxed, and lands lightly on the ground. If the cat made up its mind that it didn’t want to fall, it would become tense and rigid and would just be a bag of broken bones upon landing. …So, instead of living in a state of constant tension and clinging to all sorts of things that are actually falling with us because the whole world is impermanent, be like a cat. Don’t resist it.”

Be like that cat, I tell myself on Geoff’s birthday. Feel it, let yourself fall, see what’s at the bottom of the well. Embrace impermanence, you know how.

We had dental appointments that day, made months ago, down at UConn. I love my dentist and was glad to see him, find out my old teeth were in fine shape.

“Let’s go out to lunch,” I said to John. “And since we’re down here, maybe go to Lux, Bond and Green and look for that ring we were going to get for my eightieth birthday present. Though there’s no way I’ll find what I want.”

I had a vision for this ring, a replacement for one I’d worm for over fifty years. Silver and gold bands entwined—I’d looked online and found nothing resembling my idea and was resigned to finding a jeweler to make one.

We tried a new middle eastern restaurant in West Hartford center and the kale salad with hummus and feta was purely delicious. Stopped at a chocolate shop, a spice store brimming with fabulous smells.

Down the street a bit, we walked into Lux, Bond and Green, West Hartford’s answer to Tiffany’s, I’d always thought. Hit by the glittering cases of gold and gems, I almost wanted to leave—Too fancy, I thought. They’ll have nothing I want here.

A salesperson approached us with a warm smile and offer to help. I told her what I was looking for. She walked to a nearby case, unlocked it, and pulled out a display of rings on a black velvet pad.

“This one?” she said, placing a silver four-strand ring on my finger with a large smile. Connecting the top two strands was a gold x. It fit perfectly.

John was smiling in agreement. “Let’s get it,” he said immediately. “I want you to have it.”

It was only a few days later I realized Geoff had given me a birthday present. The four strands were our family, him in it still, the gold x was a kiss.

We are all falling out of a tree, every moment of our lives.

The day I’d dreaded had become celebratory, redeeming, joyful. Maybe, after all these years, I’ve made some progress in letting go.

Maybe.

**********************

I am thrilled to announce I’ve received three Pushcart nominations in the last month, two for poems— “Where I Come From,” in Italian Americana, and “Things” in The Comstock Review—and one for an essay in Story Circle Network’s anthology Real Women Write: Seeing Through Your Eyes—a piece I wrote about doing writing workshops with women at a homeless shelter in Hartford and how it affected me.

My book, I Am Not a Juvenile Delinquent, How Poetry Changed a Group of At-Risk Young Women, is currently on sale for 30% off on Mango.bz @mangopulishinggroup until January 31st. Grab a copy for yourself or as a gift in time for the holidays!

I wish for all of you a way to navigate the upcoming holiday season with as much joy as you can muster in these troubling times.

With love, Sharon