Alex Ross's Blog, page 82

October 2, 2017

Week of too many concerts

There is a logjam of interesting events in New York and environs this week. Boulez's Répons will resound in the Park Avenue Armory. Ashley Fure's The Force of Things will have a run at Peak Performances in Montclair, NJ. BAM is presenting Matthew Aucoin's chamber opera Crossing, a Walt Whitman meditation. Yarn/Wire is playing Enno Poppe at the Kitchen. The Barnes Ensemble, a new resident group at the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, will cap a week of workshops, master classes, and chamber concerts with a public performance on Oct. 8, featuring works of György Ligeti, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Zosha di Castri, Clara Iannotta, Eric Wubbels, and Chaya Czernowin — the last two serving as composers-in-residence. The reunited Art Ensemble of Chicago will make an appearance at Miller Theatre on Oct. 6 and then proceed to the October Revolution festival in Philadelphia, which is also featuring the Sun Ra Arkestra, Anthony Braxton, Claire Chase, Zeena Parkins, and So Percussion. And the Momenta Quartet will host the third edition of its Momenta Festival, with a two-day dance tribute to Ursula Mamlok following.

October 1, 2017

For Si Newhouse

Stockhausen's Mittwoch, 2012.

Si Newhouse, the longtime owner of The New Yorker and other Condé Nast magazines, has died at the age of eighty-nine. David Remnick, the New Yorker's editor, pays affecting tribute to him on our website. For years, he was to me an unapproachably mysterious character, glimpsed from afar in the cafeteria at 4 Times Square, where Condé Nast moved in 1999. Then, when my book The Rest Is Noise appeared, I got to know him slightly. He read the book and invited me to dinner at the apartment that he shared with his wife, the architectural historian Victoria Newhouse. It was difficult to concentrate on one's meal with masterpieces of twentieth-century art hanging on the walls. Si seemed to respond to one of the governing questions of my book: why, when artistic modernism was so widely celebrated, did twentieth-century musical modernism remain obscure? He took an interest in possible connections between Cage and Pollock, Feldman and Rothko. I had made these arguments before, but never with an actual Pollock looming over me.

He was an undemonstrative, soft-spoken man, who often appeared at Condé Nast wearing a bulky sweatshirt. Conversations with him were intimidating, not so much because he was a man of wealth and power — his rigorously hands-off approach to the stewardship of The New Yorker meant that it made no difference whether one impressed him or not — but because he was so obviously avid to hear about something new and notable. You wanted to satisfy his almost boyish curiosity. In the past decade I often saw him and Victoria at new-music concerts, the more avant-garde the better: the Talea Ensemble, the JACK Quartet, the Austrian Cultural Forum, Miller Theatre, and so on. He was up for almost anything, though he drew the line at Xenakis in rowboats; in that case, Victoria ventured out alone. In the spring of 2012, I told him that I was planning to go that summer to Bochum, to see John Cage's Europeras, and to Birmingham, for Stockhausen's Mittwoch. When I arrived in Bochum, there they were, Si and Victoria: the doubleheader had sounded to them like a fun vacation. He went on attending concerts even when medical challenges made the experience difficult. This was at once heartbreaking and uplifting to see. He was a man of deep culture, even if he hesitated to put his impressions into words. "That was very interesting," he'd say. Likewise, I hesitate to put into words who he was and what he represented. He remained mysterious, yet I regarded him with ever more gratitude and awe. It would have sounded idiotic to express that to him, but I wish I had done so all the same. Deepest condolences to Victoria and the Newhouse family.

September 27, 2017

Cather notes

On the Willa Cather Memorial Prairie, 2011.

In this week's issue of The New Yorker I write about Willa Cather's home town of Red Cloud, Nebraska, and, more widely, about the present state of understanding of the great novelist's work. Anyone interested in exploring the more or less infinitely rich world of Cather can begin with the three superb Library of America volumes devoted to her: Early Novels and Stories, Later Novels, and Stories, Poems, and Other Writings. The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, published in 2013, has instantly become an essential volume. A large quantity of Cather's writing is available at the website of the Willa Cather Archive at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, including her complete journalism up to the year 1894. In a longer draft of my piece, I quoted her journalistic début, from the Nebraska State Journal, in 1893. She was, awesomely, nineteen:

The church was crowded; hundreds of men and women were sitting in front of the minister who stood under the twisted brass chandeliers and spoke of the brotherhood of man. He looked over the well dressed, well educated audience and his interest quickened under the pleasant knowledge that he was being appreciated. His white face flushed and his thin lips trembled with enthusiasm, enthusiasm over the beauty of the women in the audience, the grandeur of the voluntary by Haydn that died from the great moaning pipes of the organ, and over his own eloquence and conscious power. He grew earnest over man's eternal brotherhood, he spread his hands in eloquent gestures. As he quoted an extract from Browning he took a white hot house rose from the cut glass rose bowl beside him and shook the water gently from its leaves. He laid the fleshy white petals against his nostrils with evident satisfaction, then dropped it again into the water. Rich, melodious words dropped from his tongue, and his voice had in it a sympathetic quiver born of excitement and the grandeur of his subject. At last he closed with five of the grandest lines that Shakespeare ever wrote and sat down among the palms and drew toward him a silver pitcher of ice water, and the thunder of the pipe organ took up the strain and went on preaching of the brotherhood of man.

I trust at least a few readers put down the paper that day and asked themselves, "Who the hell is this?" The assurance is what impresses. Cather is already writing from a lordly remove, yet with empathy and a detective's eye. The best line in the piece is "five of the grandest lines that Shakespeare ever wrote.” Her editor may well have asked: "Which lines are those?" But Cather knew that we didn’t need to know: for this pompous minister, Shakespeare is décor, and any lines will do.

Many people provided assistance as I worked on this article and on the Cather chapter of my forthcoming book Wagnerism. (In the book I will have a great deal more to say about Cather's musical masterpiece, The Song of the Lark.) Andrew Jewell, Guy Reynolds, Beth Burke, Melissa Homestead, and Kari Ronnig were excellent hosts at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln last year, when I gave a talk entitled "The Schindelmeisser Factor," unveiling my minor discovery about Cather's childhood piano teacher. My friends Jay Yost and Wade Leak, unabashed Catherites, inspired me to revisit and write about Red Cloud; at the Cather Foundation, Ashley Olson, Lynette Krieger, Tracy Turner, Tom Gallagher, and Jarrod McCartney were all hugely helpful and generous with their time; and members of the extended Yost clain, including Suzy Yost Schulz and the Hansens (Matthew, Sally, Dennis), gave me a sense of Red Cloud life and history. I've also gained much from the Cather writing of John Murphy, Joseph Murphy, Janis Stout, Ann Romines, and my esteemed New Yorker colleague Joan Acocella, among many others. At the Cather Archive site you can read back issues of Cather Studies, a rich fund of contemporary scholarship.

At the end of the article, I mention my grandfather the geologist Clarence Samuel Ross. This is not the first time the late Dr. Ross has received notice in the pages of The New Yorker. He figures in John McPhee's masterly 1996 article "The Gravel Page," recounting the contributions made by American geologists in tracing the origins of Japanese balloon bombs during World War II. "A damned good man on rocks" was the verdict upon him. My parents, also mineralogists, were delighted to be quoted in an article by the great McPhee, who is universally revered in the geological profession. He will be appearing at the New Yorker Festival next week. I will be there, no doubt with many of my colleagues, taking notes.

September 25, 2017

A walk in Catherland

September 24, 2017

Booklist

New and recent titles of interest.

Brent Hayes Edwards, Epistrophies: Jazz and the Literary Imagination (Harvard UP)

Ann Powers, Good Booty: The Sexual Power of Music (HarperCollins)

Daniel K. L. Chua, Beethoven and Freedom (Oxford UP)

Jonathan D. Bellman and Halina Goldberg, eds., Chopin and His World (Princeton UP)

Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, eds., Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America (MIT Press)

Zeynep Tufekci, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest (Yale UP)

September 21, 2017

Nightafternight playlist

— Gregory Spears, Fellow Travelers; Aaron Blake, Joseph Lattanzi, Mark Gibson conducting the Cincinnati Symphony (Fanfare Cincinnati)

— Bernstein, Complete Solo Piano Works; Leann Osterkamp (Steinway)

— Bach, Solo Cello Suites; Thomas Demenga (ECM; digital 9/29, physical 11/17)

— Bach, Solo Cello Suites; Richard Narroway (Sono Luminus)

— Dynastie: Concertos by JS, JC, WF, and CPE Bach; Jean Rondeau, Sophie Gent, Louis Creac'h, Fanny Paccoud, Antoine Touche. Thomas de Pierrefeu, Evolène Kiener (Warner)

— George Lewis, Assemblage; Ensemble Dal Niente (New World)

— Leonard Bernstein the Composer (Sony box set)

September 18, 2017

Design for Living

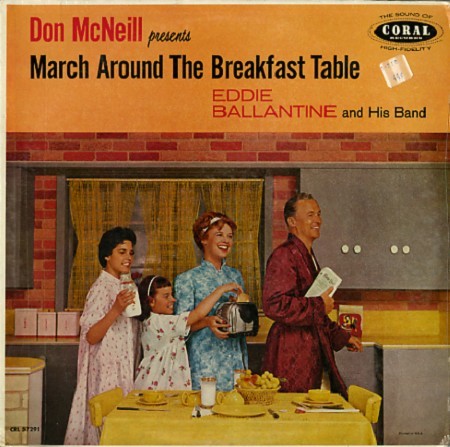

Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder's Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America (MIT Press) is a handsomely illustrated volume devoted not to the incontestable classics of the LP era but to the more utilitarian margins of the catalogue — background music, instructional records, travel albums, and the like. Some highlights are Music to Paint By, Music for a German Dinner at Home, and, of course, March Around the Breakfast Table. (Is it advisable to march with a live toaster?) Many of the record covers have that unreal mannequin quality typical of fifties and sixties advertising, allied with blatantly sexist or vaguely racist tableaux. But some reach into the higher echelons of graphic art: Saul Bass's design for Frank Sinatra Conducts Tone Poems of Color is so lovely to behold that listening to the record seems superfluous. In the same vein, I recommend two recent Taschen volumes: Jazz Covers and Alex Steinweiss, the latter celebrating the pioneer and undisputed master of album-cover art.

Design for Living*

Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder's Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America (MIT Press) is a handsomely illustrated volume devoted not to the incontestable classics of the LP era but to the more utilitarian margins of the catalogue — background music, instructional records, travel albums, and the like. Some highlights are Music to Paint By, Music for a German Dinner at Home, and, of course, March Around the Breakfast Table. (Is it advisable to march with a live toaster?) Many of the record covers have that unreal, mannequin quality typical of fifties and sixties advertising, allied with blatantly sexist and vaguely racist tableaux. But some reach into the higher echelons of graphic art: Saul Bass's design for Frank Sinatra Conducts Tone Poems of Color is so lovely to behold that listening to the record seems superfluous. In the same vein, I recommend two recent Taschen volumes: Jazz Covers and Alex Steinweiss, the latter the inventor and undisputed master of the album-cover genre.

*borrowed from Flanders and Swann

September 16, 2017

John Wooldridge, bomber-composer

The British actor Dirk Bogarde made two famous film appearances as composers: as Liszt in Song Without End and as a musicalized version of Gustav von Aschenbach in Visconti's Death in Venice. One might add to the list, with an asterisk, Bogarde's performance as Wing Commander Tim Mason in the 1953 war picture Appointment in London, about the exploits of RAF bomber crews. True, Bogarde's character is not seen to have anything to do with music. But John Wooldridge, who came up with the film's story and co-wrote the screenplay, was a working composer, and the script is based on his experiences. Wooldridge also wrote the film's score — a rather unusual case of a composer evoking himself on film.

The best account of Wooldridge's life available is a Music Web International essay by his son, Hugh Wooldridge. During the war, he flew ninety-seven missions, an extraordinarily high number. He continued to compose while serving in the RAF. Hugh Wooldridge writes: "During the first three years of the war, and in between flying, he wrote his first and most notable musical work — a symphonic poem The Constellations (1944) working alternately on borrowed pianos and the local padre’s organ. Much of this was sketched during the long bombing missions over occupied mainland Europe." In 1944, Artur Rodzinski and the New York Philharmonic read The Constellations at a rehearsal, and Rodzinski promised that he would play a new work if Wooldridge downed five German planes. When Wooldridge achieved that number, Rodzinski led the composer's A Solemn Hymn to Victory, in late 1944. He received rather tepid reviews from the New York critics: Olin Downes, in the Times, said the piece was "noble in intention" but "technically not mature." Be that as it may, Wooldridge broke the Atlantic speed record while flying home.

After the war, Wooldridge produced a large quantity of film scores, as well as a number of concert pieces. The music for Appointment in London shows no lack of craftsmanship, although it can't be described as subtle. The film makes for uneasy viewing today, given what we know about the Allied campaign of area bombing. But it does capture the extraordinary psychic strain placed upon the likes of Wooldridge. "A crew member on a British bomber had a shorter life expectancy than an infantryman in the trenches of World War I," Ben McIntyre has written. Sadly, having survived all that, Wooldridge died in a car accident in 1958.

September 7, 2017

For John Ashbery

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers