Alex Ross's Blog, page 27

September 4, 2023

Nightafternight playlist

New and recent releases of interest.

Monteverdi, Vespro della beata Vergine; Renaud Brès, Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, Céline Scheen, Adrien Mabire, Perrine Devillers, Zachary Wilder, Marouan Mankar-Bennis, Antonin Rondepierre, Pierre Gallon, Raphaël Pichon leading the Ensemble Pygmalion (Harmonia Mundi)

Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 5, Schulhoff, Five Pieces for String Quartet (orch. Manfred Honeck and Tomáš Ille); Honeck conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony (Reference)

George Walker, Sinfonias Nos. 1-5; Gianandrea Noseda conducting the National Symphony, with Shana Oshiro, DeMarcus Bolds, Daniel J. Smith, V Savoy McIlwain, and Kevin Thompson (National Symphony)

It Floats Away from You: works of Alexandre Lunsqui, Beth Wiemann, Li Qi, Lei Liang, Vid Smooke, Jeffrey Gavett, Christian Carey, and Chris Cresswell; Byrne:Kozar:Duo (New Focus)

Il concerto segreto; works of Luzzasco Luzzaschi and Francesca Caccini; La Néréide (Ricercar)

Franck, Hulda; Jennifer Holloway, François Rougier, Véronique Gens, Ludivine Gombert, Matthieu Lécroart, Christian Helmer, Marie Gautrot, Artavazd Sargsyan, Edgaras Montvidas, Judith van Wanroij, Sébastien Droy, Guilhem Worms, Matthieu Toulouse, Gergely Madaras conducting the Chœur de Chambre de Namur and the Orchestre Philharmonique de Liège (Bru Zane)

Nørgård, Three Nocturnal Movements, Symphony No. 8, Lysning; John Storgårds conducting the Bergen Philharmonic (BIS)

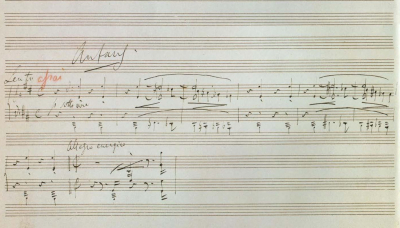

Liszt

September 3, 2023

Dream mattress

September 2, 2023

A Reinhard Febel moment

Reinhard Febel · slumberland

I recently revisited a 1988 Wergo disc devoted to the now seventy-one-year-old German composer Reinhard Febel, who emerged in the nineteen-eighties as the practitioner of a quizzical, deconstructive approach to traditional musical materials — a mode of composing "with" rather than "in" tonality, he called it. At the time, I was particularly fascinated by his vocal-orchestral piece Das Unendliche, which I featured on my college radio show, Music Since 1900. Wanting to catch up on what Febel has been doing lately, I found Slumberland, premiered in 2019. It's in quite a different vein from Febel's quasi-tonal early works. The dominant texture is one of pointillistic clouds of piano sound — six pianos are the core of the ensemble — from which more defined figures gradually emerge. The title is taken from Winsor McCay’s comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland, which ran in the New York Herald from 1905 to 1911, although the composer also had in mind the venerable Berlin bar of the same name, over which he happens to live. Score and notes can be found here here. Also of note: the 2007 orchestral piece Berceuse avec cauchemar, which meditates ominously on the Chopin Berceuse.

Notes on the Wagner Group

August 27, 2023

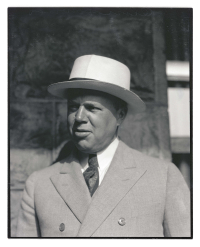

Revisiting Olin Downes

Continuing to catch up on recent issues of American Music, I read with great interest Carol A. Hess's article "'If That Be Treason, Let Them Make the Most of It!': Olin Downes, the Spanish Civil War, and Civil Liberties," in the Summer 2022 issue. Downes, the chief critic of the New York Times from 1924 until his death in 1955, is not generally seen as one of the titans of the profession: he lacked the stiletto-sharp style of Virgil Thomson, his chief rival, and his judgments on contemporary composers bordered on the philistine. In my book The Rest Is Noise I had a certain amount of fun at his expense, noting how his worshipful attitude toward Sibelius may actually have facilitated that composer's creative block, particularly when Downes was badgering the composer to finish his Eighth Symphony. In one letter, Downes sent along urgings from his mother, who said that Sibelius must move on from the Eighth to write a Ninth equaling Beethoven's.

There is, however, much to be said in Downes's favor. At a time of rising snobbery, elitism, and high-mindedness in classical-music discourse, he was an unabashed populist, speaking for the "common man." He was a vigorous opponent of the "No Applause Rule," arguing that audiences should applaud whenever they felt like it. And — this is the core of Hess's research — he was a formidable voice on the American left, organizing fundraisers and speaking at meetings. As the Cold War stoked repressive measures against leftist artists, Downes spoke up in the pages of the Times. In 1947, he protested the deportation of Hanns Eisler, and the following year, in an essay titled "Composing by Fiat," he gave a prickly response to reports of Zhdanov-era persecution of composers in the Soviet Union, observing that political oppression was also taking place on American soil, notably in Hollywood. He wrote: "Great nations, including our own, do lip-service to democracy while clearly showing that they do not believe in democracy at all, but only in power politics and force." Hess has uncovered correspondence and memos revealing tensions between Downes and Times publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger, who, to his credit, ultimately supported his critic's independence. Hess concludes:

In often timid times, Downes took risks. As a result he suffered financial loss, endured the hassle of mindless paperwork and interrogation, and was the object of both hyperbole and downright falsehood. With his fundraising (which often yielded large sums of money) and his stature as an orator, Downes effectively lived a double life, balancing his career in music with activism. He walked a similar tightrope in explaining himself to Sulzberger, whom he seems ultimately to have respected, whatever their differences of principle, rhetoric, and tone.

To compare Downes and Thomson is an interesting exercise. The latter cannily shifted with the political tides, switching from New Deal-ish writings in the thirties to a sterner, anti-populist line after 1945. He spoke unswervingly for an élite musical community and mocked crowd-pleasing musicians such as Toscanini, Heifetz, and Horowitz. Downes, it might be said, was a lesser critic but a better musical citizen.

Image from the Oregon Historical Society.

August 22, 2023

August 21, 2023

The price of Price

In "Capitalism and the Future of American Classical Music Scholarship," an article for the Winter 2022 issue of American Music, musicologist Douglas Shadle writes about the challenges of performing Florence Price's music in the wake of an acquisition of her work by the firm of G. Schirmer:

According to my understanding of current U.S. copyright law, Price’s unpublished manuscripts will enter the public domain in January 2024. At the time of the acquisition, Schirmer therefore had five years to extract as much profit as possible from the Price catalog before others could freely pursue their own projects. Indeed, the cost of renting Price’s orchestral works is prohibitively expensive for smaller organizations, thus limiting its accessibility despite the promise of global availability. In October 2021, a staff member at a moderately sized orchestra in the South publicly disclosed that the rental fee for Price’s piano concerto cost the ensemble $2,200, or over $100 per minute of this relatively brief work. A standard rental agreement obliges the orchestra to return the scores and parts without keeping a copy with bowings and other interpretive markings in the orchestra’s library for future use. Schirmer also charges a per-measure fee for music examples published in books or journals, as is their right. Yet the fee dissuades analytical scholarship in the near term since it will no longer be necessary for writers who can create their own examples from the unpublished manuscripts after 2023.

Shadle talks more about these issues on Will Robin's Sound Expertise podcast. Also worth heeding is Mary Jane Leach's commentary on troubling tensions surrounding the performance and discussion of Julius Eastman.

The end of Mostly Mozart

August 19, 2023

A Paulus Spongopoeus Gistebnicenus moment

In the 2001 edition of the New Grove, Gistebnicenus, also known as Pavel Jistebnický Spongopeus, was described as "arguably the most prolific Bohemian composer of his time."

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers