Alex Ross's Blog, page 235

April 26, 2011

Miscellany: Durham, LBJ, etc.

I went to see Bill Morrison's film The Miners' Hymns, which I mentioned a couple of weeks ago. Voiceless, almost textless, only fifty-two minutes long, it is a beautiful and devastating work, having the weight of tragedy. There's one more showing at Tribeca Film Festival on Thursday.... Spring for Music, Tom Morris's festival of inventive orchestral programming at Carnegie Hall, begins on May 6. On Thursday, Spring for Music hosts an online chat with composer Steven Stucky, whose concert drama August 4, 1964 will be played by the Dallas Symphony on May 11.... The Black Pearl Chamber Orchestra, an ethnically diverse group under the direction of Jeri Lynne Johnson, presents a "jazz hot" program in Philadelphia on April 28: music of Milhaud and Stravinsky. Over the weekend comes the premiere of Paul Moravec's short opera Danse Russe, a comedy about the making of The Rite of Spring, with a libretto by our old friend the Hon. Terry Teachout.... Make Music New York has announced some events for the 2011 edition of its midsummer musical jamboree: John Luther Adams's Inuksuit in Morningside Park, a participatory iPhone work by Aaron Siegel, and a rendition of Louis Andriessen's Hoketus on the outdoor balconies of the New York Stock Exchange.... There's a XenakisFest this week in Tempe, Arizona.... Starting on May 1, the Cleveland Orchestra will present three all-Italian programs at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Modern fare includes Scelsi, Dallapiccola, Berio, and the American premiere of Stefano Scodanibbio's fourth string quartet.... Congratulations to the magnificent Manny Ax, who on Thursday will play his hundredth concert with the New York Philharmonic.

April 23, 2011

For Peter Lieberson

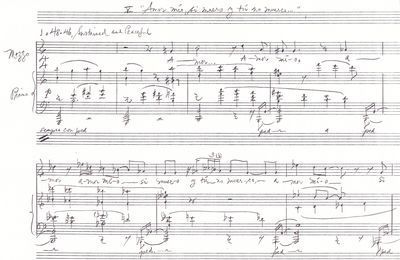

"My love, if I die and you don't," from Peter Lieberson's Neruda Songs; Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, with James Levine conducting the Boston Symphony (Nonesuch 79954).

I am devastated to learn of the death of the composer Peter Lieberson. He passed away in Israel this morning, at the age of sixty-four, of complications arising from a lymphoma that had been diagnosed not long after the death of his beloved wife, the mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, in 2006. Despite the debilitating effects of the illness and its treatment, Lieberson went on composing; the New York Philharmonic presented his song cycle The World in Flower in 2009; the Boston Symphony played Songs of Love and Sorrow, his memorial for Lorraine, in 2010; and the National Symphony premiered Remembering JFK earlier this year. I am told that he was working on a percussion concerto when he died; he had been receiving medical treatment in Israel since last December.

Lieberson was a magician of harmony. He wrote with a rare combination of modernistic rigor and Romantic sensuality, the latter coming ever more to the fore in recent years. Among his major works are the First Piano Concerto, written for Peter Serkin; Drala, a sumptuous symphony in miniature; the opera Ashoka's Dream, which had its premiere in Santa Fe, in 1997; and the Neruda Songs, the last of which can be heard above. His father was Goddard Lieberson, the mighty president of Columbia Records, his mother the dancer Vera Zorina. He studied composition with the late Milton Babbitt, among others. He was also deeply versed in Tibetan Buddhism, and for a time ran a Tibetan training center in Nova Scotia. "What makes the human life so poignant is the recognition of its profound impermanence,'' he told David Weininger last year.

I hope it is not indulgent to mention that I had a personal connection with Peter. I took a course from him in college — a wonderfully discursive theory class in which we spent week after week admiring isolated chords in Schubert's "Erlkönig." He had the final word on my non-career as a composer, describing my end-of-term Sonatina as "most interesting and slightly peculiar." Although I never again met Peter in person, we struck up a correspondence after Lorraine passed away. When I sent him a copy of my book The Rest Is Noise, he sent, in return, the manuscript reproduced above, which I will always treasure. In the original hardback edition of the book I failed to mention his music, and for the paperback I decided to insert a sentence about Neruda Songs, comparing it to Strauss's Four Last Songs. It is now the last work named in the book.

April 22, 2011

No one could defeat death

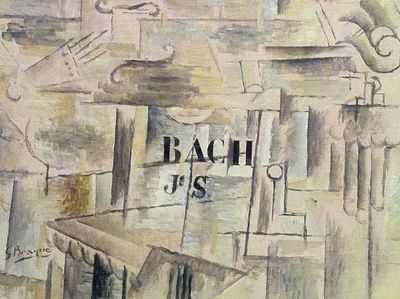

"Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt," from BWV 4, "Christ lag in Todesbanden"; John Eliot Gardiner conducting the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists (Soli Deo Gloria 128, Vol. 22 of the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage).

April 20, 2011

Nietzsche was wise

"When one is young, one deifies and despises without that art of nuance which is the finest gain in life, and understandably one must atone hard for having so battered people and things with Yes and No. Everything is arranged so that the very worst of tastes, the taste for the unconditional, should be cruelly duped and abused, until the subject learns to put a little art into his feelings, even to make a stab at the artificial: that is what the real artists of life do."

— Beyond Good and Evil

April 19, 2011

Fricka knows (II, expanded)

As noted below, I have a piece in this week's New Yorker on a single, highly charged moment in Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung: a ten-bar passage that plays in the orchestra at the end of Act II, Scene 1 of Die Walküre. Essentially, I've tried to write a piece that approaches Wagner in microcosm, rather than from the grand historical perspective that so often dominates discussion of the composer. Aiding me in this quest are the scholars Thomas Grey and Barry Millington, the mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe (who sings Fricka in the Met Walküre that opens on Friday), and the conductors Justin Brown, Simone Young, Simon Rattle, Christoph von Dohnányi, and James Levine (on the podium this Friday, if all goes well). All offered their thoughts about the music. Accompanying the article is a podcast with the New Yorker's Blake Eskin.

Starting at 7:20 in the YouTube video above, you can hear most of the music I discuss in the piece. Fricka, Wotan's wife and the goddess of marriage, has just conducted an interrogation in which she takes apart her husband's grandiose scheme to win back the cursed ring. She leaves him in a psychologically shattered state, spiraling toward the self-accusatory monologue of the following scene. You first hear Fricka's closing arioso ("Deiner ew'gen Gattin"), in which she demands that Brünnhilde, Wotan's loyal Valkyrie, uphold her eternal values and allow the rebellious hero Siegmund to die. Wotan swears that Brünnhilde will do so ("Nimm den Eid"). Then come those ten remarkable bars in E-flat major (see also the post below). Finally, Fricka's parting words to Brünnhilde—"Your father has something to tell you" was Blythe's wonderful paraphrase to me—and the orchestral announcement of the motif of the Curse. Rosalind Plowright is Fricka, Bryn Terfel is Wotan.

I used a couple of favorite older recordings on the podcast. For "Deiner ew'gen Gattin," I chose Margarete Klose, recorded in 1938 as part of EMI's incomplete prewar Walküre set. Klose is even more penetrating on this rare recording from the 1940 Bayreuth Festival, which a YouTube poster retrieved from an undisclosed source. (I consulted a couple of discographic experts, who believe it to be authentic.) For Wotan's monologue, I chose Hans Hotter on the 1955 Bayreuth Ring, which many Wagner connoisseurs now prize as the one Ring to rule them all, to take a phrase from Tolkien. Hotter's delivery of the lines "Endloser Grimm! Ewiger Gram!"—"Endless rage! Eternal grief!"—tears at the heart, and Joseph Keilberth's orchestra positively boils behind him.

I'm fascinated by the dissonance that rumbles in the orchestra as this passage begins. First, the double basses and timpani play octave Cs, which are sustained throughout. Over that drone there appears a chord of D-flat major, creating a semitone clash with the C. Then a D-natural — the second note in the rising bass-trumpet line — sounds against the D-flat, dissonance doubled down. And when a C-flat is added to the D-flat harmony, it, too, jars with the fundamental C. After Wotan's first cry ("O heilige Schmach!"), the sequence is repeated, now with a chord based on G-flat. For a moment, you effectively have C major colliding with G-flat major. These clashes are sufficiently spread out in the orchestra that you don't hear them as painful conflicts: it's more an immense, vague groaning, as Wotan's world is loosed from its moorings.

Fricka knows (II)

As noted below, I have a piece in this week's New Yorker on a single, highly charged moment in Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung: a ten-bar passage that plays in the orchestra at the end of Act II, Scene 1 of Die Walküre. Essentially, I've tried to write a piece that approaches Wagner in microcosm, rather than from the grand historical perspective that so often dominates discussion of the composer. Aiding me in this quest are the scholars Thomas Grey and Barry Millington, the mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe (who sings Fricka in the Met Walküre that opens on Friday), and the conductors Justin Brown, Simone Young, Simon Rattle, Christoph von Dohnányi, and James Levine (on the podium this Friday, if all goes well).

Starting at 7:20 in the YouTube video above, you can hear most of the music I discuss in the piece. Fricka, Wotan's wife and the goddess of marriage, has just conducted an interrogation in which she takes apart her husband's grandiose scheme to win back the cursed ring. She leaves him in a psychologically shattered state, preparing to embark upon the self-scouring monologue that dominates the following scene. You first hear the closing arioso ("Deiner ew'gen Gattin") in which Fricka demands that Brünnhilde, Wotan's loyal Valkyrie, uphold her eternal values and allow the rebellious hero Siegmund to die. Wotan swears that Brünnhilde will do so ("Nimm den Eid"). Then come those ten remarkable bars in E-flat major. Finally, Fricka's own parting words to Brünnhilde ("Your father has something to tell you" was Blythe's wonderful paraphrase to me) and the orchestral announcement of the motif of the Curse. Rosalind Plowright is Fricka, Bryn Terfel is Wotan.

Miscellany: Philly crisis, etc.

What is happening at the Philadelphia Orchestra? Peter Dobrin gives some essential background and context.... Early reactions to the world premiere of Stockhausen's Sonntag in Köln: Seth Colter Walls, Shirley Apthorp, Claus Spahn.... Harpa Concert Hall, the new home of the Iceland Symphony, opens in Reykjavík next month; the façade is by Olafur Eliasson, the acoustics by Artec. Not long ago the project seemed doomed to extinction on account of Iceland's economic collapse. Here's my 1995 review of the Icelanders at Carnegie Hall, with Osmo Vänskä conducting.... The Urban Remix project has come to Times Square.... Tonight at St. Paul's Chapel at Columbia, the College of New Jersey Orchestra and Chorale will collaborate with Argento in presenting Mozart's Requiem together with Georg Friedrich Haas's Klangräume ("sound spaces"), which were written to tie together Mozart's original fragmentary score.... Andrew Rose of Pristine Audio has begun a remastering of Wilhelm Furtwängler's 1953 RAI recording of the Ring.... I'm very happy to have helped inspire Michael Century's forthcoming performance of Ann Southam's late-period masterpiece Simple Lines of Enquiry. It's at EMPAC, in Troy, NY, on April 25th.... The musicologist Alexander Silbiger has supervised an online thematic catalogue of the music of Girolamo Frescobaldi, whose pivotal role in the history of Western music is still not sufficiently appreciated. I'm presently delving into Tactus's monumental 12-CD box set of Frescobaldi's complete keyboard works.

April 18, 2011

Fricka knows

April 14, 2011

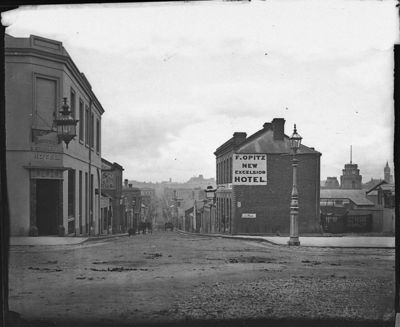

Wagner gazes upon Australia

In 1877 Wagner received a letter from an Australian correspondent, telling him of a Melbourne performance of Lohengrin. This was his reply. Period photograph of Melbourne from the State Library of New South Wales.

Most honored sir!

Your news has pleased me very much, and I cannot refrain from thanking you for it.

May you see to it that my works are performed among you in English; only then can they be understood intimately by an English-speaking public. We are hoping that this will happen in London.

We (my family and I) were uncommonly interested in the enclosed views of Melbourne; as you were so kind as to offer to let us have more, I assure you that you would thereby delight me greatly.

Please extend my compliments to Herr Lyster [conductor of Lohengrin], and even in your distant part of the world may you maintain a friendly feeling toward

your much obliged

Richard Wagner

Bayreuth, 22 October 1877

My translation; the original text is in Jennifer Marshall, "Richard Wagner's Letter to Australia," Miscellanea Musicologica 14 (July 1985).

Miners' hymns

Above is a trailer for Bill Morrison's film The Miners' Hymns, a melancholy celebration of coal-mining culture in the great northern English city of Durham. The film is centered on the Durham Miners' Gala, an annual summertime meeting which, from the late nineteenth century until the Thatcher era, brought thousands of celebrants into the city. The gala was famous not only for its union activism but for its carnival atmosphere, its massed choral singing, and its myriad brass bands. Morrison's film has a soundtrack by the Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson — a brooding ambient creation, recorded in Durham Cathedral, for large brass ensemble, organ, percussion, and electronic sounds. I became aware of Jóhannsson's music when I picked up his gently hypnotic disc Englabörn at 12 Tónar in Reykjavík in 2005; I've had mixed experiences with his records since, but this one packs a considerable punch. Although I can't yet comment on Morrison's film, I've relished his masterly manipulation of "found" footage since I saw his contribution to John Moran's The Death Train of Baron von Frankenstein at La MaMa in 1993; he is best known for Decasia, his film symphony with Michael Gordon. The Miners' Hymns plays at the Tribeca Film Festival later this month.

Interestingly, The Miners' Hymns is not the only Durham mining disc recently to cross my desk. NMC, the superb English new-music label, has issued a CD version of Big Meeting, an hour-long tape-collage composition by the Australian-born composer David Lumsdaine. In 1971, Lumsdaine and several of his students — he was teaching at Durham University at the time — set out with microphones to create an "electronic poem" based on that year's Big Meeting (as the gala is also called), recording hymns, songs, speeches, conversations, and brass bands all around the city. The piece, which was finished only in 1978, was originally in quadrophonic sound; Lumsdaine faced difficulties in attempting to convert the work to stereo, and a planned LP release never came about. For NMC, he has finally made a full digital remastering that seems a convincing alternative to the quadrophonic original. This YouTube trailer gives a flavor of it. Big Meeting is remarkable not only as a technical feat — I can't think of a electronic work that gives a more vivid sense of movement within a particular geography —but also as a haunting evocation of a lost world. If the sound of the miners' hymn in Durham Cathedral doesn't bring a tear to your eye, you must be one of the Koch brothers. Although the miners' gala carries on, its raison d'être is gone; the last of the Durham mining pits was closed in 1992.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers