Alex Ross's Blog, page 227

July 4, 2011

Did Tosca survive?

On my jazz-beflecked visit to the Castel Sant'Angelo, I had a thought that surely has occurred to countless Puccini-minded tourists before me: where did Tosca jump from exactly? If you look out across the Tiber from the upper terrace, as in the photo above, it seems as though the doomed diva would have a straight shot down. But there's a ledge just under:

Unless Tosca had an extraordinary running jump, she would have simply landed there, and, somewhat anti-dramatically, would have needed to leap again. She might of course have gone off the side, into the courtyard below:

It's a considerable drop, but perhaps not automatically fatal, and it lacks style. The angles from the back are entirely unsuited to grandiose self-obliteration. What occurred to me is that we could be looking at a Reichenbach Falls situation. Tosca might have disappeared off the front, landed on the ledge, and then inched round the side and clambered through the little window there, even as Spoletta and the soldiers peered from above and concluded that she had plunged to her death:

I look forward to the shocking sequel, Tosca Returns.

July 3, 2011

Noise in Hebrew

June 30, 2011

Addio, Roma

This is my last night in Rome. Ardent thanks to the American Academy in Rome for hosting me this past month, and, not incidentally, for giving me the view you see above; I have had the extreme good fortune of serving as the Academy's Marian and Andrew Heiskell Visiting Critic for the current term. I've stored up material for a few more Roman posts, not to mention two New Yorker articles and a chunk of Wagnerism, so the Italian accent will persist here a little longer.

Studio with a view

Don't shoot the piano player

I came upon a jazz concert in a somewhat unexpected place in Rome. The artists are Eleanora Colatei, Stefano Cicconetti, Paolo Bernardi, and Marco Contessi. If you don't recognize the sword held aloft in the corner of the last frame, it's this.

June 29, 2011

For Bernard Herrmann

The master of Hollywood film music would have been one hundred today. Strangely, the anniversary has gone mostly unmarked by American musical institutions; one important exception is the Minnesota Opera, which staged Wuthering Heights in April. I wrote about Vertigo for the Times in 1996. Brian Gittis, in an online piece for the Paris Review, describes what happens when daily life is scored with Herrmann music.

Musical Venice

Even with hordes of tourists filling the streets, Venice remains an intensely musical city, from the bell towers on down. On my trip there last week, I picked up a copy of Olivier Lexa's new book Venise, l'éveil du baroque, an illustrated guide to the Venetian musical Baroque. It's published by the Venetian Centre for Baroque Music. I had great fun consulting Lexa's book as I ambled about, listening for echoes of Venice's many golden ages. I was delighted to discover, for example, that Vivaldi once lived at Fondamenta del Dose No. 5879, just a few steps from the hotel where Jonathan and I were staying. The red priest occupied the mezzanine floor from 1722 to 1730; during this time he wrote The Four Seasons.

Between 1705 and 1722, Vivaldi lived in two adjoining houses on the Campo Santi Filippo e Giacomo, first on the right and then on the left. I cannot vouch for the quality of the Hotel Rio, which is ranked #253 of 445 hotels in Venice on Tripadvisor.

Many musical tourists gravitate to the "Vivaldi church," Santa Maria della Pietà, to which the Ospedale della Pietà, Vivaldi's long-time employer, was attached. In fact, the present church, by Giorgio Massari, was begun in 1745, after Vivaldi's death, although it has been suggested that the composer offered advice to the architect before leaving for Vienna in 1740. Lexa notes that fragments of the original Pietà buildings can be seen in and around the Metropole Hotel next door:

I was sorry to miss Jordi Savall's presentation of Vivaldi's Teuzzone at Versailles this summer, the cornerstone of a major Vivaldi-Venice festival — I'd originally hoped to make the trip. A recording of Teuzzone will be forthcoming in Naïve's complete Vivaldi edition.

I wandered for an hour trying to find the spot where the Teatro San Cassiano Nuovo once stood. In this historic venue, opera had what might be called its "second birth," becoming a fully theatrical entertainment. During the 1641 Carnevale, both Monteverdi's Return of Ulysses and Cavalli's Didone were playing at San Cassiano; what a season that must have been. I never quite found the right place — I now realize that I should have stood on the notorious Ponte delle Tette and looked south down the Rio di S. Cassiano — but the blogger Mes Carnets Vénitiens caught the view here. (The theater stood where the gardens of the Palazzo Albrizzi are now, on the right.) It seems merely a coincidence that a Ponte Cavalli is nearby:

The Palazzo Strozzi, on the Rio di Santi Apostoli, was the home of the poet and librettist Giulio Strozzi and of his adopted daughter Barbara Strozzi, a composer of exceptional talent:

I must now break away from the Baroque and revisit the topic of Wagner. My main reason for going to Venice, if reason was needed, was to patrol sites that will figure in my not at all imminent third book, Wagnerism. The Meister came to Venice six times, and, of course, died in the city in 1883. On his first visit, in 1858-59, he stayed first at the Danieli, the famous old hotel near the Piazza San Marco, and then in rented rooms at the Palazzo Giustiniani-Brandolini, on the Grand Canal. It was in the latter space that he wrote much of Act II of Tristan und Isolde; in an evocative description of the period in My Life, the composer suggests that the shepherd's-pipe melody in Act III of Tristan was inspired by the late-night chant of a gondolier. Wagner's rooms were, I believe, on the left-hand side of the palazzo, on the first floor (second row of windows):

Needless to say, we had to stop for coffee at Caffè Lavena, Wagner's favorite haunt during his final Venice stay. He was there on the day before he died:

The café honors its famous customer with a plaque:

I went back to the Palazzo Vendramin-Calergi for another look. Here is a vaporetto view, with the windows of Wagner's personal rooms partly visible behind the fence:

The courtyard, with the Wagner apartment behind the shuttered windows on the left:

On the wall facing the Grand Canal there is an ornate fin-de-siècle monument honoring Wagner, with an inscription by Gabriele d'Annunzio. John Barker, in his very useful book Wagner and Venice, translates it thus: "In this palace the spirits heard the last breath of Richard Wagner become eternal, like the tide that laps the marble stones." The tablet was installed with great ceremony in 1910, with a band playing the Meistersinger overture and selections from the Ring:

June 28, 2011

Listen to no silence

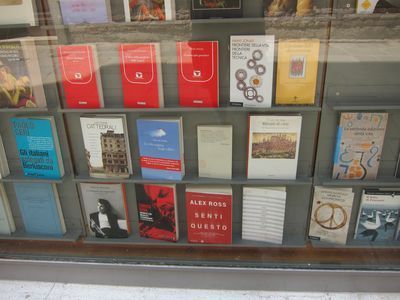

Senti questo, the Italian translation of Listen to This, is now in stores. I saw it in a bookshop window next to Kyle Gann's superb Cage study No Such Thing As Silence. The Italian edition, like the forthcoming English-language paperback, contains my recent New Yorker essay on Cage.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers