Alex Ross's Blog, page 217

October 2, 2011

Thought of the day

". . . yes by God there's a corpse that will dance for some time yet and leave the world precisely as it finds it."

— James Joyce in Tom Stoppard's Travesties

October 1, 2011

Miscellany: John Schaefer's Radiohead solo, etc.

The LA Phil will unfurl a very attractive-looking Green Umbrella on Tuesday, Oct. 4: Zosha Di Castri's La forma dello spazio, Feldman's Viola in My Life 1 and 2, Takemitsu's Rain Coming, and Georg Friedrich Haas's chants oubliés. Writes Haas: "The title refers to late works by Franz Liszt (Valses oubliés, Romance oubliée) – Liszt's technique of presenting one-part melodies in a different sound environment (often that of the piano) is applied here to the possibilities of the chamber orchestra." ... John Adams, who is overseeing Green Umbrella as LA Phil's Creative Chair (a great season overall), also has a lovely piece on Mahler in the New York Times Book Review.... The new building of the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest is named after György Ligeti.... The Red Light New Ensemble opens its season on Monday night with a "Music as a Map" program.... For some years now, Gotham Early Music Scene has been fighting to change the widespread impression that New York's early-music community lacks lustre in comparison with Boston's or the Bay Area's, not to mention scenes in a dozen European cities. They're making headway, as sampler concerts this weekend should testify.... Scandal! Anne Midgette has got into a public dispute with Plácido Domingo.... My American Musicological Society post below inspired Will Robin to start a "fake AMS" game on Twitter, the results of which are summarized on NewMusicBox. All this is good-natured fun — I have deep respect for so many brilliant scholars out there, and Will is himself a musicology grad student.... I saw Radiohead on Thursday night at Roseland. Three random notes: 1) I'd never noticed that one of Jonny Greenwood's ondes Martenot lines in "The National Anthem" seems to quote the Andante sostenuto theme from the second movement of Sibelius's Second (see 4:08); 2) Yes, that's the voice of WNYC's John Schaefer on Jonny's Cagean radio in the first minute — talk about Soundcheck!; 3) The version of "Bloom" that opened the show was one the most awesome things I've heard them do, a dancing juggernaut.

September 29, 2011

A Luca Marenzio moment

The famous opening of this madrigal — a setting of Petrarch's "Solo e pensoso" ("Alone and pensive") — has the top voice rising by chromatic steps, over the span of a major ninth; the summit is reached at 0:50. The effect is wonderfully vertiginous, evoking the poet's solitary wanderings. But the really ecstatic, spine-tingling event occurs at 1:08, when (in the transposition on this recording) the harmony slips eerily from E minor to G minor and then cadences in D major. The reason it sounds like pure Romanticism for a moment is that on the third beat of the G-minor bar (around 1:10) the alto rises from D to E-natural and holds the E into the next bar while the other voices go to D major. The ache of that suspension is universal. Something quite similar happens as Isolde breathes her last (listen for the suspension in the high winds):

The Marenzio recording is by La Venexiana, for Glossa. Isolde is, of course, La Flagstad.

September 28, 2011

The Schoenberg shelf (1)

I've been reading two recent books about the Master of North Rockingham Avenue: Sabine Feisst's Schoenberg's New World (Oxford University Press) and Jennifer Shaw and Joseph Auner's The Cambridge Companion to Schoenberg. Feisst's book, an exceedingly thorough study of Schoenberg's American years, has been long in the making and is worth the wait. It should efface prevailing conceptions of the later Schoenberg as "a controversial figure displaced in a culturally alien environment, disadvantaged, neglected, and disillusioned," to quote from the opening chapter. In place of that conception, which Schoenberg himself helped to fix in his more pessimistic moments, Feisst portrays a composer energetically if ambivalently engaged in his adopted homeland — Schoenberg died an American and left behind an American family — and determined to create a many-sided legacy. If he was an outsider to the end, it should be remembered that he was always an outsider, always an alien. Neither a "European" nor an "American" perspective can accommodate him fully: he pushed against the grain of whatever culture he inhabited. He had his intellectual formulas but was constitutionally incapable of lazy or simplistic thinking. The same cannot be said of many of his self-appointed followers, who imprisoned his work in sanctimonious ideology. To quote Schoenberg's scarily prophetic aphorism of 1909: "The second half of this century will spoil by overestimation, all the good of me that the first half, by underestimation, has left intact."

I thought I knew this territory fairly well from my researches for The Rest Is Noise, but Schoenberg's New World held many revelations for me — although I'm happy to see that in broad outline my own portrait of the American Schoenberg is not dissimilar. Some nuggets that jumped out: 1) Schoenberg generally did better financially from teaching in America than he did in Berlin, and even in retirement he was in no way impoverished; 2) following the hysteria over Gerhart and Hanns Eisler, in 1947, the FBI searched Schoenberg's home, becoming momentarily suspicious when they found volumes of Adolf Bernhard Marx; 3) American performances of Schoenberg were considerably more frequent than is generally believed, even before the composer arrived on these shores (between 1915 and 1933 there were at least thirty performances in Los Angeles alone; the pianist James Sykes played the Suite Op. 25 in thirty recitals between 1937 and 1951). There are many excellent anecdotes demonstrating that while Schoenberg was a severe teacher he was not a dogmatic one, and often refused to discuss the twelve-tone method even when students begged him to. Yet his imperious attitude toward performers often proved self-defeating, especially in an American culture of superficial politesse. Feisst notes that when Dimitri Mitropoulos indulged in a modest bit of choral theatrics in a performance of A Survivor from Warsaw Schoenberg reprimanded the conductor for betraying "higher taste." Mitropoulos replied: "Please, I beseech you, be more tolerant, especially when you write letters of complaint," going on to say that while he remained a devoted admirer others would be turned off. Schoenberg was duly chastened: "You are right, in my age I should not be anymore as temperamental as I was — very much to my disadvantage – during my whole life." Although Feisst plainly has affection for her subject, she does not omit less flattering material — for example, Schoenberg's bizarre fantasy of becoming the savior of the Jewish people, broadcasting messages from a ship that was to have been supplied by President Truman.

One item I'd like to quote in its entirety, since I had never seen the full text. It is a letter that Schoenberg wrote on behalf of Henry Cowell when Cowell was convicted of sexual contact with a seventeen-year-old boy. Some colleagues cut Cowell off when the arrest was made; Charles Ives, notoriously, stopped writing to him for a time, although recent researches by Leta Miller and Rob Collins suggest that Ives's attitude was not as censorious as Harmony Ives, his wife, wished others to believe. ("I didn't know what to write or say or what to think or do," Ives himself wrote to Cowell.) Schoenberg was more generous — and sudden bursts of generosity were by no means uncommon in him:

Henry Cowell is probably the most outstanding American musician. Not only is he a composer of greatest originality, but what he has done for the musical culture of America can not be expressed in a few words, because it is history. It is his merit that through him American musicians became interested in those modern movements in music which are predominant in the old country. I have known Henry Cowell for more than ten years and I know that he is the most distinguished, noble minded, idealistic character; he is absolutely without selfishness; he is good natured and full of regard for others. Thus one will understand how distressed I was when I learned he was arrested and convicted; and one will conceive that I did not believe at first that this could be true. I could not believe that a character like that described before could be capable of such violations. But when I realized it was true, I understood what the great interpreter of the human soul and passions, William Shakespeare, said: 'There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.' May I add that it would be the most regrettable loss for the musical culture of America if a man like Henry Cowell had to suffer longer for a temptation which seems to have been even stronger than such an extraordinary character.

You can see the facsimile in the Schoenberg online archive. A handwritten draft reveals that Schoenberg was uncertain at first whether to attribute the quotation to Shakespeare or Schiller. "There are more things in heaven and earth" — so it is also with Schoenberg himself, whose music exceeds the bounds of any philosophy that has been devised to celebrate, explain, or attack it. Feisst's book shows how much there is left to be learned about this astonishing figure in modern cultural history, whose true, full biography has yet to be written.

I'll address the Cambridge Companion in a future post.

September 27, 2011

An Ervín Schulhoff moment

This moment is inspired by the arrival of ECM's Edition Lockenhaus, a handsome five-CD retrospective that includes a fine account of Schulhoff's Duo and a spectacular rendition of his Sextet, one of the finest chamber works of the nineteen-twenties. The original recordings, paired with late Shostakovich, made a great impact on me circa 1988. I was lucky to visit Lockenhaus some years later.

September 26, 2011

Electric Pasta (AMS addendum)

Pasta as Anna Bolena

Several correspondents, among them the excellent Roger Evans, have asked whether I might consider an addition to my list of "top 10 paper titles" from the forthcoming conference of the American Musicological Society. Indeed, I'm not sure how I overlooked Ellen Lockhart's tantalizing offering, "Giuditta Pasta and the History of Musical Electrification." The title deserves extra points for avoiding the overfamiliar catchphrase-colon-paraphrase formula. By way of penance I append the entire abstract:

This paper charts the development of metaphors of musical electrification, from the first experiments in "animal electricity" into the realm of Italian operatic performance. In the last decade of the eighteenth century, northern Italy was the site of a scientific revolution, when Luigi Galvani discovered that frogs' legs could be animated by means of electrical current. His experiments in "animal electricity" were reproduced in salons and on stages across Europe, often enhanced with lighting effects and musical accompaniment. Music itself was often described as an electrical force, which could transmit charge from one body to another, or redistribute the electrical currents within an individual, without the need for metal conductors. One result was an early form of music therapy: in his 1816 medical treatise, Angelo Colò suggested that epileptic seizures could be cured by means of musical accompaniment, directing the patient's electrical current rhythmically away from the brain and into the limbs. Another consequence was a new lexicon and theoretical apparatus for describing music's effects on the listener. Writers drew most frequently on metaphors of electrification in describing Italian operatic performance—and in particular the performance of women. This had some basis in electric science: women were believed to carry a negative charge, and thus the female singer could act as a lightning rod, drawing the positive charge in the atmosphere into her body (which would display the symptoms of shock), and transmitting it into spectators through song. The earliest performer to be described consistently in such terms was Giuditta Pasta, in writings by Stendhal, Chorley, Ritorni, and Cantù. For these writers, Pasta's ability to electrify her audience derived both from her mercurial voice and from her distinctive acting style: she was known for suddenly stiffening her body into poses lasting two to three seconds, directly in time with musical events; her teacher, Talma, reportedly taught her that an action should precede its music in a flash, the way lightning precedes thunder. This research into electric animation may enrich our understanding of performative presence, musical effect, and the interaction of visual and musical media within early ottocento opera.

September 25, 2011

Radiohead in New York

The English composers Radiohead are having a brief residency in New York. On Saturday Night Live last night, with Clive Deamer as guest second drummer, they played "Lotus Flower" and a dreamily potent new song called "Staircase"; you can watch videos here. Thanks to a bass-playing friend, I got to watch from the audience at Rockefeller Center; it was my first time in Studio 8H, the historic Toscanini venue. Photos of the great man still hang in the corridors, mingling oddly with pictures of Sprockets, the Coneheads, and the like. (There's a common link, though: Alec Baldwin, who hosted the show, is the announcer for the New York Philharmonic's radio broadcasts, and serves generally as classical music's chief celebrity spokesperson.) Anyway, Radiohead will appear tomorrow on the Colbert Report, and on Wednesday and Thursday they'll play at Roseland. Tickets for the shows go on sale tomorrow at 10AM, and will probably be gone a minute or two later.

I first heard Radiohead at the Hammerstein Ballroom in 1997, during the OK Computer tour. The second song on the setlist was "Just," with its octatonic scale spiraling gigantically upward; I was converted. I wrote at the time:

OK Computer has fewer stately airs than The Bends, but it adds layer upon layer of weird beauty. The sound is somehow tall: ideas unwind in every register. "Paranoid Android" is a symphony in six minutes, moving from a shuffling introduction to a hardcore scherzo, then from a slow chorale on the words "From a great height" to a hammering coda. Throughout the album, contrasts of mood and style are extreme: a couple of the songs could almost have been sung by Sinatra (or so it's fun to imagine), while a couple of others, rescored for bass clarinets, might win appreciative shrugs from new-music cognoscenti at the Knitting Factory. This band has pulled off one of the great art-pop balancing acts in the history of rock.

My 2001 profile of Radiohead is in my book Listen to This. As I've said before on this blog, chronicling the band's European and American tour was one of the great experiences of my life. Having given up pretensions of writing about non-classical music, for the most part, I'm happy now to relate to them as a fan rather than as a critic. The photo above was taken at Red Rocks in Colorado.

September 24, 2011

Top ten AMS paper titles

The annual meeting of the American Musicological Society will take place in San Francisco in November. As with any academic conference, some scholars seem to have worked a tiny bit harder than others to arrest the eyes of those browsing the program. There is, of course, no guarantee that these will be the most interesting papers in the conference. (Hat tip: Will Robin.)

Francesco Dalla Vecchia, "Sopranos Gone Wild: Flashing in Seventeenth-Century Venetian Opera"

Craig Monson, "'How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria?' — 'They Would Claw Each Other's Flesh If They Could': Conflicting Conformities in Convent Music"

David Kasunic, "Beethoven in the Background: Music and Fine Dining in Nineteenth-Century France"

Amanda Eubanks Winkler, "High School Musicals: Understanding Seventeenth-Century English Pedagogical Masques"

Rachel Cowgill, "Filling the Void: Theosophy, Modernity, and the Rituals of Armistice Day in the Reception of John Foulds's A World Requiem"

Jessica Wood, "An Old World Instrument for Cold War Diplomacy: The Touring Harpsichord in 1950s Asia"

Elaine Kelly, "Late Beethoven and Late Socialism in the German Democratic Republic"

John Howland, "Nobrow Pop in the New Millennium?: Nico Muhly and Post-2000 Chamber Pop"

Paula Higgins, "Josquin and the Dormouse: Aesthetic Excess, Masculinity, and Homoeroticism in the Reception of Planxit autem David"

Joseph Auner, "Weighing, Measuring, Embalming Tonality"

Footnote: Prof. Winkler is also the author of O Let Us Howle Some Heavy Note: Music for Witches, the Melancholic, and the Mad on the Seventeenth-Century English Stage.

September 23, 2011

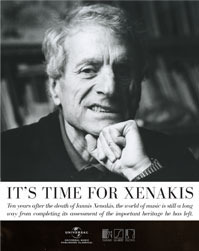

Hey kids, what time is it?

The title may bring unexpected Howdy Doody resonances for American readers, but this thirty-one-page pamphlet is a fine short introduction to the master of controlled chaos. The text makes considerably more idiomatic use of the English language than does the online summary.

September 22, 2011

Miscellany: Hilary Hahn interviews a fish, etc.

Above is a video preview for the SONiC Festival, the major new-music event of the fall New York season. More than a hundred composers aged forty or under, covering a very broad stylistic spectrum, will be featured in a series of nine concerts in October.... Mode Records is currently curating a series of shows at the Stone. Two notable events this weekend: a program including Mauricio Kagel's Ludwig van on Saturday night, and Margaret Leng Tan singing and playing Cage's Four Walls on Sunday.... In Slate, Jan Swafford has a beautiful story on the sad fate of Charles Ives's summer home.... Always worth reading: reviews of new music at the Proms by 5:4. Of the premieres I heard online (only five, to be sure), Simon Holt's Centauromachy might have been my favorite.... Ekmeles, a vocal ensemble whose repertory ranges from Gesualdo to the contemporary avant-garde, is a promising addition to the New York scene. On Oct. 6 they will sing James Tenney, Pascal Dusapin, Johannes Schöllhorn, and Peter Ablinger at ISSUE Project Room's future home on Livingston Street.... "Do you have any advice for people who would like to become fish?" Hilary Hahn, having apparently sat through too many robotic interviews, has responded with a Cagean provocation.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers