Alex Ross's Blog, page 204

February 7, 2012

Halftime music

There's much discussion of a Chrysler ad that aired during the Super Bowl, a popular American sporting contest. I was pulled in not only by the rasp of Clint Eastwood's voice but also by the intriguingly dour score, which avoids the ersatz Coplandisms you might expect in this context. (Compare the infamous Rick Perry "Strong" ad.) It reminds me a little of Jóhann Jóhannsson's music for The Miners' Hymns. A few minutes' search on the Internet yielded the information that the score is the work of the Portland musician Alison Ables, who plays in the instrumental trio Strange Holiday. The horn parts are played by Lydia Van Dreel, of the University of Oregon School of Music and Dance. The producer is Collin Hegna, another musician active in the Portland indie scene, and the current bass player of the neo-psychedelic band Brian Jonestown Massacre. No wonder Karl Rove doesn't like it.

Boston in vain

Jeremy Eichler, masterfully evoking a recent performance of Georg Friedrich Haas's in vain by Sound Icon: "...the lights go out and you listen in complete, disorienting darkness. The walls are gone. The musicians are gone. Your neighbor is gone. It is night, and you are suddenly alone with this music of a strange, tremulous beauty."

Hitler's favorite opera?

Various media outlets are making much of a story about the Deutsche Oper being forced to reschedule a gala performance of Wagner's Rienzi that would have coincided with Hitler's birthday. Amplifying the outrage are claims that Rienzi was "Hitler's favorite opera," "Hitler's favorite Wagner opera," or, more oddly, "Hitler's favorite Wagner production." I recall James Jorden some time ago skeptically cataloguing contradictory statements about Hitler's Lieblingsoper, though I can't seem to find the post. In any case, typing the relevant phrases into Google shows the problem. The special opera is said to have been Rienzi, Die Meistersinger ("probably Hitler's favorite," Ernst Hanfstaegl said), Götterdämmerung, Tristan, Parsifal, Lohengrin, Eugen d'Albert's Tiefland, and The Merry Widow. To avoid trouble, German opera houses may have to avoid programming any of these works on April 20.

The main thing that is known about Hitler and Rienzi is that a 1905 performance of the opera in Linz inspired him to begin thinking of a political career. Hitler identified strongly with Wagner's portrayal of the "people's tribune" — a nobler figure than the ultimately decadent demagogue of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel — and drew political lessons from Rienzi's defeat, as Hans Rudolf Vaget, the brilliant Thomas Mann scholar, has noted. In the essay "Hitler's Wagner," which appears in the anthology Music and Nazism, Vaget observes that in 1930 Hitler evidently spoke to Otto Wagener of his "special liking" for Rienzi. (Wagener had assumed that Hitler wouldn't care for the opera because it shows a popular leader falling prey to intrigues. They were deciding whether to see Rienzi or Rosenkavalier.) And, yes, the autograph manuscript of Rienzi may have gone with Hitler to the bunker, along with the original scores of Die Feen and Das Liebesverbot and various manuscripts related to the Ring. (Interestingly, though, Sven Friedrich, the director of the Wagner archive in Bayreuth, believes that this material never left Hitler's villa in Berchtesgaden, and may still resurface.) So Rienzi had a powerful, even pivotal, effect on Hitler. But there is no basis for calling it his "favorite opera."

In the end, the question should be left unanswered: in the case of Hitler, above all others, we should not assume more knowledge than we have. The documentary record does hint, however, that Hitler, like so many others, may have been most deeply affected by Tristan — ironically, the least "political" of the music dramas. In a notebook from Landsberg prison, Hitler wrote that he was "dreaming of Tristan and his kin." In January 1942, according to Monologe im Führer-Hauptquartier, 1941-1944, he said, "Tristan is surely [Wagner's] greatest work. We have the love of Mathilde Wesendonck to thank for it." ("Der Tristan ist doch sein grösstes Werk. Es war die Liebe zur Mathilde Wesendonck, der wir das verdanken.") And Hitler's secretary Christa Schroeder recalled him saying that he wished to hear Tristan when he died. He had a primal encounter with Tristan at the Vienna Court Opera in 1906; years later, in conversation with the director Alfred Roller, he could describe the production in detail. In 1998, while working on a piece about Wagner and anti-Semitism for The New Yorker, I puzzled over the fact that extant descriptions of the episode in the Hitler literature did not name the conductor. So I sent a fax to the Staatsoper, asking who led Tristan on May 8, 1906. It was, unsurprisingly yet shockingly, Gustav Mahler.

February 5, 2012

Philip Glass at 75

Number Nine. The New Yorker, Feb, 13 and 20, 2012.

Bonus track: ISSUE Project Room.

Previously: The Satyagraha protest.

Nightafternight playlist

Recordings of interest.

— Berg, Beethoven, Violin Concertos; Isabelle Faust, Claudio Abbado conducting the Orchestra Mozart (Harmonia Mundi)

— Tune thy Musicke to thy Heart: Tudor and Jacobean music; Stile Antico, Fretwork (Harmonia Mundi)

— EndBeginning: music of Brumel, Crecquillon, Clemens, Josquin, Jackson Hill; New York Polyphony (BIS)

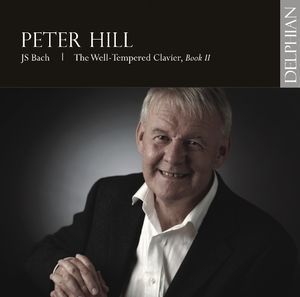

— Bach, Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II; Peter Hill (Delphian)

— Sibelius, Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5; Osmo Vänskä conducting the Minnesota Orchestra (BIS)

— Cage, Number Pieces vol. 6; Essential Music (Mode)

— Besides Feldman; Rozemarie Heggen, Hilary Jeffery, Pamelia Kurstin, Patrick Pulsinger (col legno)

— Wim Henderickx, Tejas and other works; Martyn Brabbins conducting the Royal Flemish Philharmonic (RFP 003)

February 3, 2012

CD of the Week: Peter Hill's Bach

February 2, 2012

Owens spricht

In advance of a recital on Feb. 21, the splendid Eric Owens takes questions from fans on Carnegie Hall's YouTube channel. (There are three other videos in the set.) His goal on any given night, he says here, is to "not phone it in." So far, he is most definitely succeeding. My question: will there be a Kurtis Blow encore?

February 1, 2012

Miscellany: Mostly Carnegie

The major musical event of the winter/spring season, by my lights, is the San Francisco Symphony's American Mavericks Festival, based variously at home, in Ann Arbor and Chicago, and at Carnegie Hall. In addition to four brilliantly programmed MTT/SFS programs — who could say no to an evening of Ruggles's Sun-Treader, Feldman's Piano and Orchestra, and Henry Brant's metamorphic orchestration of the Concord Sonata? — Carnegie has assembled a neat array of auxiliary events, including a So Percussion Cage tribute, an Alarm Will Sound show, a night with the indie bands WHY? and Danielson, a program of William Basinski and Tristan Perich, a JACK Quartet adventure (the great Ruth Crawford Seeger quartet!), and a recital by Lisa Moore. I covered the original Mavericks festival for the New York Times.... When the Berlin Philharmonic comes to Carnegie later this month, Deutsches Haus at NYU will mount an exhibition of David Friedemann's portraits of Philharmoniker musicians from the nineteen-twenties, with a chamber performance appended.... Seated Ovation smartly critiques Carnegie's 2012-13 season announcement — which, Beethoven excess aside, does have a strong lineup of premieres, not to mention a Joyce DiDonato recital entitled "Drama Queens".... Great Performers 2012-13 will bring, among other things, Paul Lewis playing the Schubert B-flat-major Sonata, Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting Wozzeck, Herreweghe conducting the "Christmas" Oratorio, a Timothy Andres recital, and the New York premiere of John Adams's The Gospel According to the Other Mary.... Georg Friedrich Haas's in vain is played by Sound Icon in Boston this Friday.... Beginning on Friday, the Dessoff Choirs mount a festival around Bach's Mass in B Minor, with various contemporary works in the mix, including Ingram Marshall's September Canons and Robin Holloway's Gilded Goldbergs. Dessoff director Chris Shepard blogs about the festival here.... The second edition of the Ecstatic Music Festival opens on Saturday, with works by Jherek Bischoff and company.

Gayby at SXSW

On a personal note, I'm ecstatically happy to say that Gayby, the feature-length directorial debut by my husband, Jonathan Lisecki, has been selected to play at the SXSW Film Festival. I have a tiny cameo in the movie, as does Dan Johnson.

January 31, 2012

Denk's New Yorker debut

When Jeremy Denk began blogging at Think Denk, it quickly became apparent that he was the liveliest writer-pianist since Glenn Gould. In this week's New Yorker, Denk makes his formal debut as an essayist, writing about his experiences recording the piano sonatas of Charles Ives. Here is a sample:

My Ives addiction started one summer at music camp, at Mount Holyoke College. I was twenty and learning his Piano Trio. There's an astounding moment in the Trio where the pianist goes off into a blur of sweet and sour notes around a B-flat-major chord. I knew the moment was important, but I wondered, was my sound too vague or too clear? (A recurring interpretative problem in Ives is discovering the ideal amount of muddle.) I was also puzzled about where this phrase was going. I'd been taught that phrases were supposed to go somewhere, yet this musical moment seemed serenely determined to wander nowhere.One afternoon, the violinist of the group and I were driving off campus and happened to cross the Connecticut River. Looking out of the window, he said, "You should play it like that." From the bridge the river seemed impossibly wide, and instead of a single current there seemed to be a million intersecting currents — urgent and lazy rivers within the river, magical pockets of no motion at all. The late-afternoon light colored the water pink and orange and gold. It was the most beautiful, patient, meandering multiplicity.

Instantly, I knew how to play the passage. Even better, Ives's music made me see rivers differently; centuries of classical music had prettified them, ignoring their reality in order to turn them into musical objects. Schubert uses tuneful flowing brooks to murmur comfort to suicidal lovers; Wagner has maidens and fateful rings at the bottom of a heroically surging Rhine. Ives is different. He gives you crosscurrents, dirt, haze — the disorder of a zillion particles crawling downstream. His rivers aren't constrained by human desires and stories; they sing the beauty of their own randomness and drift.

Denk says more about Ives in a conversation on the New Yorker podcast. On Feb. 13, he will appear at the Housing Works Bookstore Café, in a new series pairing musicians with writers; the writer in question will be the New Yorker literary critic James Wood, who is, as readers of Best Music Writing 2011 know, also a brilliant musical commentator. I may be obsolete.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers