Alex Ross's Blog, page 198

March 26, 2012

Czech Noise

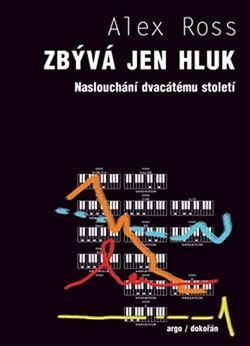

Zbývá jen hluk: Naslouchání dvacátému století is now available from Argo Press in Prague. The Rest Is Noise is now available in eleven languages, with five more translations in the works.

Ross-Boulez

When will Diana Ross and Pierre Boulez finally make a record together? She is sixty-eight today, he eighty-seven. Happy birthday to them both, and to my friend Sean.

March 25, 2012

Kennedy Center column

Culture Complex. The New Yorker, April 2, 2012.

Bonus: Nixon in conversation with Ginger Rogers, Sept. 17, 1971.

For more of Nixon's thoughts on the Kennedy Center and other musical matters, go here.

Simpson in America

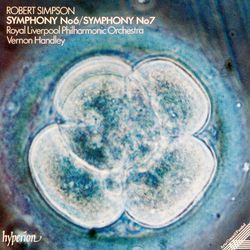

B. W. Grant Barnes, a knowledgeable observer and generous supporter of the Los Angeles arts scene, has written an in-depth report, for Norman Lebrecht's blog, of a recent West Coast performance of Havergal Brian's Symphony No. 27. It was not only the American premiere of the work but its first outing since the 1979 world premiere. The responsible party was the Orange County High School for the Arts Symphony Orchestra, a much-lauded group with a remarkable range of repertory: a recording on the MMC label has them playing works of Magnus Lindberg, Brett Dean, Hans-Joachim Hespos, Éric Tanguy, and Steven Stucky. Christopher Russell, OCHSA's longtime conductor, has made a specialty of neglected twentieth-century symphonists: Brian, Rued Langgaard, and Robert Simpson, among others. Oddly, just before coming across Barnes's report I'd been researching American performances of Simpson's eleven symphonies, and one of very few mentions I'd found in news archives was an OCHSA rendition of the Seventh in 1999. (Another was a performance of the Third by the Oklahoma City Symphony in 1974.) I have admired Simpson's music since hosting a show called "The Twentieth-Century Symphony" on WHRB-FM in the late eighties; indeed, I made my debut as a music critic reviewing Hyperion's CD of the Sixth and Seventh for the WHRB Program Guide. I will have a bit more to say about Simpson in The New Yorker soon, in advance of the Lost Dog New Music Ensemble's performances of the Horn Quartet at two concerts next month — as far as I know, the first nod to Simpson in New York in more than two decades. Despite various attempts over the years, I have yet to acquire a strong taste for Havergal Brian, but there is still time before night falls.

B. W. Grant Barnes, a knowledgeable observer and generous supporter of the Los Angeles arts scene, has written an in-depth report, for Norman Lebrecht's blog, of a recent West Coast performance of Havergal Brian's Symphony No. 27. It was not only the American premiere of the work but its first outing since the 1979 world premiere. The responsible party was the Orange County High School for the Arts Symphony Orchestra, a much-lauded group with a remarkable range of repertory: a recording on the MMC label has them playing works of Magnus Lindberg, Brett Dean, Hans-Joachim Hespos, Éric Tanguy, and Steven Stucky. Christopher Russell, OCHSA's longtime conductor, has made a specialty of neglected twentieth-century symphonists: Brian, Rued Langgaard, and Robert Simpson, among others. Oddly, just before coming across Barnes's report I'd been researching American performances of Simpson's eleven symphonies, and one of very few mentions I'd found in news archives was an OCHSA rendition of the Seventh in 1999. (Another was a performance of the Third by the Oklahoma City Symphony in 1974.) I have admired Simpson's music since hosting a show called "The Twentieth-Century Symphony" on WHRB-FM in the late eighties; indeed, I made my debut as a music critic reviewing Hyperion's CD of the Sixth and Seventh for the WHRB Program Guide. I will have a bit more to say about Simpson in The New Yorker soon, in advance of the Lost Dog New Music Ensemble's performances of the Horn Quartet at two concerts next month — as far as I know, the first nod to Simpson in New York in more than two decades. Despite various attempts over the years, I have yet to acquire a strong taste for Havergal Brian, but there is still time before night falls.

March 24, 2012

Video of the day: alla turca

A mehter, or Ottoman military band, at the Topkapi Palace.

Sitting behind Wagner

Rudolph Aronson, Theatrical and Musical Memoirs: "It was my good fortune during the first Wagner festival to have a seat directly behind that of the master himself, and this gave me an opportunity to see how intently he followed every movement on the stage and in the orchestra. He was a little, wiry, nervous man, and just before the conclusion of each act he would spring to his feet, rush behind the scenes to consult with the artists, superintend the settings, and then appear before the curtain to acknowledge the plaudits of the audience. As the curtain arose for the next act he would quietly resume his seat."

March 23, 2012

Meet the critics

Lewis Rosenthal, in

"The Critics at the Play" (The Theatre, 1887), gives a rundown of New York's music critics:

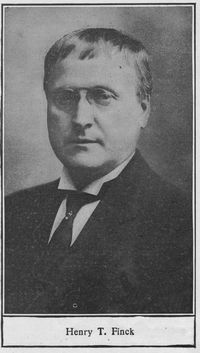

What's on the boards at the Metropolitan Opera House this Saturday afternoon? Never mind what: let's go to have a glimpse of the critics. There is Frederick A. Schwab, of the Times, short, compact, alert, curling his tawny mustache. A little to the left sits tall, courteous, military-looking John P. Jackson, of the World, chatting with bluff, genial, broad-shouldered Leopold Lindau, of the Figaro and the Dramatic News. To the right I see athletic Henry E. Krehbiel, of the Tribune, whispering to blondish Henry T. Finck, of the Evening Post....

Schwab ... has written spicy letters and sent lengthy dispatches from Bayreuth. I hear he is preparing some "memoirs." They are sure to be interesting. An accomplished linguist, a violinist in his hours of leisure, a man of wide general reading, Schwab is as caustic, suggestive, boulevardier in his talk as he is in his printed work....

Finck ... a graduate of Harvard and a student at Berlin and Heidelberg, is a perfect monomaniac on the subject of Wagner, and endeavors to put his readers into the same condition of mind. Jackson and Lindau, even Kobbe, of the Mail and Express, are lukewarm compared with him. He seems to date his articles Bayreuth. He dreams nightly of Siegfried and Tristan. He rides daily with the Walküre, and plays cards with the Nibelungen. I hear that he is getting ready a book on types of female beauty. Ten to one, Brünnhilde is his ideal....

Krehbiel writes learnedly, with his eye ever to the land of Wagner and Liszt. Schwab dashes off his column in a breezy, piquant style, with a marked predilection for Verdi and Gounod. Krehbiel comes out with professional elaborateness — quotes, gives dates, cites precedents. Schwab politely suggests, pithily opines, ingeniously infers.

One of the most clever, if one of the youngest, musical and dramatic critics in town is William T. Henderson ... Henderson has written verses, grave and gay; librettos, and translations of librettos; articles for magazines; letters from watering places. His column in the Times of Sunday, captioned "The Orchestra at Work," demonstrates his knowledge of the technique of the stage and of music, and his power of gentle irony and stinging sarcasm.

Little Steinberg, of the Herald, pert, saucy, snappy, always seems to be in a minority. He writes an interesting criticism, but one in which there is always a note of insincerity, a striving after effect. But who can please all the critics? ...

Bassarids in New York

Not long after he began his tenure at the New York Philharmonic, Alan Gilbert mentioned the idea of presenting a semi-staged performance of Hans Werner Henze's 1966 opera The Bassarids, one of the major works of late-twentieth-century music theater. Perhaps such an event will still come to pass; a program at the Philharmonic this week, containing an orchestral suite from the opera, certainly whets the appetite. The Bassarids, with its Auden-Kallman libretto and its darkly opulent, post-Bergian score, has long seemed a natural for the Met, but, as Peter G. Davis wrote in the Times on Sunday, for one reason or another it has never happened. Christoph von Dohnányi, who led the premiere of The Bassarids back in 1966 and remains astoundingly energetic on the podium nearly fifty years later, is leading the Philharmonic performances, the first of which took place last night. The concert suite, which Henze assembled in 2004, is drawn largely from the "third movement," the Adagio, of the symphonically structured score; it ends with the dismemberment of Pentheus by the Maenads. Henze has done a marvelous job of recasting vocal lines as instrumental solos; especially wrenching are the cello lines representing Pentheus's dying words. Avery Fisher Hall fell uncharacteristically silent as Carter Brey gave a strikingly vocal, expressive account of that solo. Dohnányi, who led with absolute authority, returned after intermission with a Schubert Ninth that began somewhat placidly and built momentum as it went along, ending in a display of furiously disciplined dynamism. A remarkable program, very much worth seeing.

Not long after he began his tenure at the New York Philharmonic, Alan Gilbert mentioned the idea of presenting a semi-staged performance of Hans Werner Henze's 1966 opera The Bassarids, one of the major works of late-twentieth-century music theater. Perhaps such an event will still come to pass; a program at the Philharmonic this week, containing an orchestral suite from the opera, certainly whets the appetite. The Bassarids, with its Auden-Kallman libretto and its darkly opulent, post-Bergian score, has long seemed a natural for the Met, but, as Peter G. Davis wrote in the Times on Sunday, for one reason or another it has never happened. Christoph von Dohnányi, who led the premiere of The Bassarids back in 1966 and remains astoundingly energetic on the podium nearly fifty years later, is leading the Philharmonic performances, the first of which took place last night. The concert suite, which Henze assembled in 2004, is drawn largely from the "third movement," the Adagio, of the symphonically structured score; it ends with the dismemberment of Pentheus by the Maenads. Henze has done a marvelous job of recasting vocal lines as instrumental solos; especially wrenching are the cello lines representing Pentheus's dying words. Avery Fisher Hall fell uncharacteristically silent as Carter Brey gave a strikingly vocal, expressive account of that solo. Dohnányi, who led with absolute authority, returned after intermission with a Schubert Ninth that began somewhat placidly and built momentum as it went along, ending in a display of furiously disciplined dynamism. A remarkable program, very much worth seeing.

Photo: Franco Pomponi as Pentheus, Châtelet, 2005.

March 22, 2012

The "complete" Bruckner Ninth

In Stereophile, Richard Lehnert writes about the Berlin Philharmonic's recent performance of the Bruckner Ninth at Carnegie Hall, with Simon Rattle conducting. At the close, Rattle and the Berliners presented a realization of the unfinished finale, by Nicola Samale, John A. Phillips, Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, and Giuseppe Mazzuca. I, too, attended the Carnegie concert, and agree with Lehnert's judgment: although the finale made a substantial impact, it seemed uncertain in places, and one could almost sense skepticism on the part of the players. Yes, the realization is necessarily speculative, especially with regard to the coda, yet Bruckner did a great deal more work on the finale than most people assume. Cohrs, in his notes to the most recent edition, observes that 557 of 647 bars come directly from Bruckner, and only thirteen bars were wholly invented by the editors. (The most common performing edition of Mozart's Requiem, by contrast, is significantly more speculative: nearly a quarter of the score is by Franz Xaver Süssmayr. I have never understood why some conductors happily serve up all that ersatz Mozart while rejecting out of hand the Mahler Tenth or this new Bruckner Ninth.) As I wrote in a Bruckner column last summer, "Some of [the finale's] strangest, most improbable gestures—trumpets leaning on a piercingly dissonant minor-ninth interval, for example—come straight out of the manuscript. Indeed, at one place in the autograph, Bruckner writes "gut" over a weird harmony combining F major with the note B, as if saying to posterity, 'Yes, this is what I want.'"

In Stereophile, Richard Lehnert writes about the Berlin Philharmonic's recent performance of the Bruckner Ninth at Carnegie Hall, with Simon Rattle conducting. At the close, Rattle and the Berliners presented a realization of the unfinished finale, by Nicola Samale, John A. Phillips, Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, and Giuseppe Mazzuca. I, too, attended the Carnegie concert, and agree with Lehnert's judgment: although the finale made a substantial impact, it seemed uncertain in places, and one could almost sense skepticism on the part of the players. Yes, the realization is necessarily speculative, especially with regard to the coda, yet Bruckner did a great deal more work on the finale than most people assume. Cohrs, in his notes to the most recent edition, observes that 557 of 647 bars come directly from Bruckner, and only thirteen bars were wholly invented by the editors. (The most common performing edition of Mozart's Requiem, by contrast, is significantly more speculative: nearly a quarter of the score is by Franz Xaver Süssmayr. I have never understood why some conductors happily serve up all that ersatz Mozart while rejecting out of hand the Mahler Tenth or this new Bruckner Ninth.) As I wrote in a Bruckner column last summer, "Some of [the finale's] strangest, most improbable gestures—trumpets leaning on a piercingly dissonant minor-ninth interval, for example—come straight out of the manuscript. Indeed, at one place in the autograph, Bruckner writes "gut" over a weird harmony combining F major with the note B, as if saying to posterity, 'Yes, this is what I want.'"

What I found really riveting about this Ninth was the changed nature of the symphonic journey. With that craggy, visceral finale looming as the new endpoint of the narrative, the symphony lost its usual air of cultish mystery, of ritual passage into silence. I suspect that the slightly quickened tempo in the first movement, the full-throatedness of the climaxes, and the sharpness of the dynamic contrasts were related to the fundamental alteration of the plan. And shouldn't this always be the case, whether or not one chooses to engage with the finale materials? Shouldn't conductors and players always at least imagine this ending? As Richard Lehnert argues, in a further comment on the Ninth, the cliché that the three-movement version is complete in itself, that the Adagio is the composer's true farewell to life, contradicts not only his practical wish to finish the work but his spiritual and philosophical beliefs. Let's not invent a quietistic scheme that Bruckner never had in mind. He has received enough condescension over the years.

March 21, 2012

Classical music returns to NBC

Rock Center with Brian Williams, an NBC news show, had a charming little feature tonight on the issue of cellphones interrupting theater shows and classical performances. There's an interview with Alan Gilbert on the subject of the famous Mahler Ninth marimba incident (weirdly, Barber's School for Scandal Overture replaces Mahler in the accompanying footage), and none other than Marc-André Hamelin makes a brief appearance, performing his "Ringtone Waltz." A longer interview with Hamelin can be found online. It was a relief to find that the reporting did not traffic in stereotypes of Stuffy Classical Snobs. Maybe NBC can now move on from covering interruptions of classical music to covering classical music itself. It has, after all, done so in the past.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers