Meg Benjamin's Blog, page 27

October 21, 2010

Red Herrings

I just finished reading a 370-page novel in which the nasty banker was revealed as a double murderer in the end. The thing is, I knew the banker was the baddie after the first fifty pages. Why? Because nobody else in the book had been set up as a possibility. So unless the writer wanted to break with romance tradition and pick a likeable character as the villain, the banker was it. QED.

Now to me, this ranks as a serious flaw in the book's plot, but that may be because I began reading romances after long experience reading mysteries. One of the cardinal rules of mystery writing is that you have to have more than a single suspect. There must be at least two or, preferably, three or four people who could have done whatever nasty thing has been done. That means constructing multiple red herrings.

A "red herring" is a false scent that supposedly diverts a hound from the true scent of its quarry (although this meaning has been challenged, according to Wikipedia). Creating alternative solutions to a mystery depending on alternative villains is standard for mystery writers. Agatha Christie is probably the past master of this—in Murder On the Orient Express she provides an entire trainload of suspects, all of whom had motive, means, and opportunity.

Romance writers don't need to go to that extreme because we're usually more interested in the romance than the mystery, but we do need to at least suggest alternatives so that the reader doesn't lose interest in the other parts of the plot. In Be My Baby, I spent a lot of time figuring out how I could conceal the identity of the nasty kidnapper. I wanted my readers to feel concerned about what was going to happen, and that meant leaving them in the dark about exactly which person they needed to fear.

If only one person in a book could have performed a particular nefarious action, I'm likely to assume that person is innocent, based on my long experience as a mystery reader. In mysteries, the bad guy is never the one you initially suspect. If it later turns out that that person is, in fact, guilty, and no doubt has ever been cast upon his guilt in the course of the novel, I'm going to be more than slightly annoyed.

Now it's possible to have the villain clearly identified from the beginning. He's the serial killer you know is on the loose or the international criminal whom the hero has been tracking for years (although in that case the identity of said criminal may, again, be the mystery). This is the usual MO for thrillers and here the plot hinge comes with how the heroine/hero is finally going to come face-to-face with the villain. This means a skillful writer is going to set up several opportunities that don't pan out in order to build suspense for the one that does (think of Clarice Starling knocking on Buffalo Bill's door in Silence Of the Lambs after all the scary preliminaries).

But whatever the plot hinge is, the reader shouldn't see it coming a mile away. The greater the surprise, the more deeply the reader is immersed in the story. And that brings me back to that nasty banker. Because I figured out the mystery so quickly, I lost interest in the plot soon thereafter. It didn't help that the romance was also pretty routine. I found myself skimming through the pages, trying to get the gist without having to read everything. And I had no problem skipping to the ending. I already knew what it was, and all I had to do was confirm my guess.

That's not the way you want your readers to feel, believe me. You want those readers to avoid looking at the ending at all costs because they don't want to spoil the suspense. And without red herrings, there's simply no suspense to spoil

October 8, 2010

Romance and Politics

It's campaign season and it's killing me. In "real life" I'm a very opinionated person—just ask my friends and family. I can fulminate with the best of them and I have very definite political beliefs. All of which I have to leave at the door when I become Romance Writer.

When I taught at Enormous State University, I was always careful to keep my political opinions to myself. I didn't want my students, many of whom held political opinions that were radically different from mine, to feel that they were in any danger of being persecuted for their beliefs. This was easier for me than for some of my colleagues since I taught things like document design and Web writing, where the subject of politics rarely came up (my friends in the history department were more hard pressed). Even so, I worked to keep my own opinions in the background. I knew what it was like to be on the receiving end of teacher prejudice more than once (when I was a kid, one teacher ridiculed me in front of my homeroom class for having a book about dinosaurs, which obviously meant I believed in (gasp) evolution).

Now as a novelist I'm in a somewhat similar position. I don't want to limit myself to any particular group of readers, and I don't want to exclude anyone from my books if I can help it. I've had some people complain about the sex scenes in my books, and I can't do much about that (or anyway, I don't intend to). Others have complained that my characters take the Lord's Name in vain, and again I'm not going to change that since I want my dialogue to sound the way most people talk. But I try not to make my characters reflect any particular political agenda because as a reader I've been annoyed when authors did that. Some authors, like Jane Haddam, can get by with having political discussions in their work, but most of us can't do it. I've found myself exasperated by characters in romance novels who suddenly start preaching about a particular social philosophy, and even more exasperated if the author inserts a hateful or absurd character who happens to share my own social philosophy. I abandoned one popular series when the author went out of her way to slam some political programs I happen to believe in. And that, of course, is the danger: when you step up on a soapbox, you risk alienating all the readers who don't agree with you.

But my beliefs do show up in my books. My characters share my values—how could they not? When they stand up for something or against something, they're reflecting my own ideas. So my leanings aren't exactly a secret, even though they may not be blatantly expressed in my writing.

Still, at times like these I have a hard time keeping my mouth shut. Every day I hear things that I find outrageous and wrong. I'm longing to say something about it on Twitter or Facebook or MySpace, or to write a really blistering blog piece about the stuff that's in the wind. But I won't. Or anyway, I don't think I will. The sound you hear is me, gritting my teeth so hard it hurts.

September 24, 2010

Snark

The Web has greatly increased the number of book reviewers available these days, both for ebooks and print books. And that's all to the good. Given the number of books being published, it's always helpful to have lots of people posting their own reactions to the latest books available, particularly if those books may appeal to a specialized audience who might not hear about them otherwise.

Some of these review sites present straightforward reviews, the kind of thing you'd find in Entertainment Weekly or Time or The New Yorker, assuming those magazines actually deigned to review romances. But there are also some sites that are largely the creatures of the Web, the ones I think of as snark sites. The reviewers on these sites do like some books, but it's not the positive reviews that their readers look for. Instead, it's the negative reviews, the books that the reviewers hate, that get the most hits. There's something about seeing somebody eviscerated in a few well-phrased paragraphs that really appeals to a lot of readers.

Predictably, most authors hate these sites. At RomCon last summer, some authors argued that reviewers owed authors at least some respect for the fact that they'd actually finished a book and gotten it published, which is, granted, more than a lot of the reviewers have done. While I can sympathize with this point of view, I don't necessarily share it. Reviewers don't really owe us anything. Much as the snarky reviews hurt (and having been on the receiving end of a couple, I can testify that they do, in fact, hurt a lot), reviewers have an absolute right to say whatever they want.

Above and beyond this right, however, I actually do understand some of the impulse behind snarky reviews because I've felt something similar. As I've said before, I once was on the faculty of Enormous State University in South Texas. I started teaching in the English department, and then moved into Communication. In this capacity, I read more papers than I want to remember—thousands, possibly tens of thousands. Early in my career I took workshops about writing comments on student papers, and I did my best to follow them. Start with something supportive. Concentrate on one or two problems the student can work with rather than trying to list everything on particularly hapless papers. Try to couch suggestions in positive language.

As I say, I did this for many years. And with many of the hapless papers, I could offer something helpful because I could see that they students were trying, albeit not getting very far. But the longer I taught, the more I lost patience with some of the papers. Some students clearly hadn't spent any time on their writing, and the results were sloppy and often well-nigh unreadable. Sometimes students went on making the same mistakes over and over, not because they couldn't recognize them but because they couldn't be bothered to do anything about them. Some students simply plagiarized something from the Web. These students pissed me off, and I found it increasingly difficult to write helpful, supportive comments on their papers. I longed, in fact, to tell them precisely what I thought—that they were wasting my time and their money in blowing off assignments. That other people wanted their seats in the class and that they might profit by seeing what awaited them in the "real world" if they continued to screw up. I wanted to write comments on their papers that were decidedly snarky.

Although some snarky reviews may be written just because the reviewer knows snark is popular, some may come from a similar impulse. The reviewer was hoping for something good and instead got something that didn't meet her expectations. The author has wasted the reviewer's time and the reviewer is, consequently, pissed.

Now the author may legitimately reply that she did the best she could, and that she (and her editor) believed the book was actually pretty good by the time it was published. But the reviewer may well be operating from the same set of feelings I had on reading the third plagiarized paper in a row. Maybe she's spouting off because she expected, and wanted, a lot more.

In romance terms, you can think of her as a disappointed suitor. And as romance writers, we all know what that leads to!

September 9, 2010

Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Social Media?

There's been a running discussion about Facebook on one of the author's lists where I'm a member. First of all, the new Facebook place app had everyone (including me) annoyed and getting instructions for turning it off. Then the discussion took a sharp turn, as these things are wont to do. One author had received a comment from a stranger who said she was a "cutie." She took umbrage. After all, her photo only showed her eyes peeking out from behind a book. How could the guy call her a cutie? Wasn't it vaguely creepy? Did it mean she was facing a potential stalker?

After that the messages came hot and heavy, mainly from authors explaining why they weren't and would never be on Facebook or MySpace or that Twitter thing (whatever it was). According to many of these authors, this social media stuff took too much time. If you got involved, you spent all your time posting instead of doing what you should be doing: writing. Better not to post at all than to waste time you could be devoting to your craft.

Dangerous, all of that stuff. Rife with mental cases, all looking for potential victims. Liable to cut into your writing time so thoroughly that you'd never finish that 200,000-word historical you've been working on for years.

Be afraid; be very, very afraid.

I must admit that, as usual, I kept my mouth shut, largely because I couldn't think of any way to staunch this flow of near-hysteria. I'm on Facebook, of course. Also Twitter, MySpace and Goodreads. As of now, I've received no inappropriate messages, and I find they're a helpful way to connect with readers and with people I know personally. But then again, I'm also a ebook author, which most of the people who were having hissy fits were not. Which means, of course, that I use digital media a lot (and it hasn't bitten me yet). I know there are cyber stalkers out there, but I haven't ever encountered one on Facebook or Twitter. I'm pretty careful about who I friend, and I don't automatically follow everybody who follows me.

As for the time issue, I've known people who were addicted to Twitter and spent an awful lot of time out there. I've known people, similarly, who spent hours on Facebook. Needless to say. I'm not one of them. I post two or three times a day and do a quick check to see what my friends have to say. Then I do, in fact, go back to writing.

But the people who never post at all are somehow certain that all of this is threatening. If they once give in and start using Twitter, they'll be sucked into some kind of infinite time sink that will keep them from ever finishing anything. And should they post anything on Facebook, Hannibal Lecter will show up on their doorstep tomorrow.

I think there's a certain retrograde flavor to all of this. A lot of print authors would very much like the publishing industry to return to what it was in, say, the nineties. Or, better yet, the eighties. At any rate, they long for a time when publicists took care of all this, and when communications from readers arrived in envelopes with stamps.

And I can sympathize with that idea up to a point. The problem is, of course, that it's not going to happen. Some writers can afford to ignore all this Internet stuff. Linda Howard, for example, still doesn't have a Web site of her own separate from her publisher's site, and I haven't seen Nora Roberts posting on Twitter lately (although, Lord knows, a lot of people post about her). But most of us have to work harder than that.

Facebook, Twitter, MySpace et al. aren't evil. They're not salvation either. They're just another way to reach people. If you prefer not to use them, more power to you. It's your choice. But please don't try to justify that choice by implying that they represent some kind of Sinister Plot to undermine the time and integrity of romance writers. Take a deep breath, pour yourself a glass of something, and get back to work.

August 27, 2010

Are You Listening?

My critique group just went through a very painful episode in which one member was banned from submitting anything for a while. The situation was this: the writer had been submitting chapters of something she'd written several years ago. This in itself is risky (as I've pointed out elsewhere ), but not really a problem. What made it a problem was that the writer wasn't bothering to revise the chapters she was submitting before she submitted them. Thus each week her submission contained the same errors she'd had the week before. The people who read her submissions became tired and frustrated with pointing out the same things over and over again. The moderator tried to explain what was wrong to the writer, suggesting that she spend some time working over the submissions, taking care of the obvious errors before sending it in, but she refused. She wanted the whole MS critiqued before she started making any changes. The moderator finally gave up and told her to stop.

I was one of the ones who was frustrated by those submissions (although, I swear, not one of the ones who complained). When you take the time to do a very thorough critique, you want to believe that your comments have some impact, that, in fact, the writer is listening to you. This doesn't mean that that writers must unfailingly do what a CP tells them to do—writers and critiquers can have honest differences of opinion on some things. But if a CP points out that you've got serious problems (like POV shifts or missing explanations or garbled prose), you need to at least take heed and try to avoid doing the same thing next time around.

I think most of us in critique groups are willing to put up with submissions that have lots of problems: That's part of the price you pay to be part of the group. But if you know the writer in question is going to have the same freakin' problems week after week, you start wanting to avoid her if possible. For example, as a former copyeditor, I have a hard time reading through mechanical errors without trying to correct them. But if the writer has so many mechanical errors that I lose the thread when I'm reading, I may start sounding testy after a while. It's one thing to miss the occasional comma. It's another to throw in semicolons with reckless abandon and without any clear idea of what they're supposed to do. Does that mean I expect other writers to be mechanically perfect from the get-go? Obviously not (although I can always dream). But it does mean I don't expect to see semicolons used with the same cluelessness in the next MS I read from this author.

In the end, it all boils down to time, as it frequently does with writing. Submissions with lots of errors take a lot longer to read. Like most critiquers, I'm willing to give other writers that time at least once or twice. But if I seen the same thing over and over again, I'm going to start feeling like my time is being wasted. And that, as Don Corleone used to say in a very different context, I do not forgive.

August 12, 2010

Damaged and Flawed

I just finished Nancy Taylor Rosenburg's thriller The Cheater. It's part of a series, although I didn't realize that when I picked it up. The heroine is a former DA who's now a judge in Ventura, CA.

She's also a mess.

Mind you, she has every right to be. In previous novels she was raped by an intruder who also raped her twelve-year-old daughter. She then murdered the man she thought was the rapist. She divorced the father of her daughter, and he was subsequently murdered by the actual rapist. She's now married to a serial adulterer who's also an alcoholic. In other words, she has Personal Problems.

Not surprisingly, the heroine herself is close to a basket case. She has flashbacks to the rape that distract her when she's holding court. She's afraid to be by herself, particularly at night. Her relationships with her husband, her daughter, and her colleagues are shaky at best. In fact, you find yourself wondering how this woman ever ended up on the bench (and hoping that you don't have anyone like her on the bench in your town).

Clearly, The Cheater isn't a romance, but I found myself wondering if a romance could have a damaged heroine like this. Frankly, I doubt it, but I'd make a distinction between the flawed heroine and the damaged heroine. Damaged heroines couldn't make it in a romance that demands people pull themselves together in the end. Flawed heroines can, and frequently do.

Flawed heroines are quirky and sometimes annoying because they're not perfect people. Contemporary romances are full of flawed heroines. Think of Jennifer Crusie's Agnes in Agnes and the Hitman or Susan Elizabeth Phillips's heroine in Natural Born Charmers or Kristan Higgins's heroine in The Next Best Thing. They have their annoying idiosyncrasies, but they're still people you can depend on, and heroines who have more admirable traits than defects.

Damaged heroines (and heroes) show up a lot more in mysteries and thrillers. Patricia Cornwell's Kay Scarpetta is damaged. So is James Lee Burke's Dave Robichaux. There are times when you wonder if they'll be able to make it to the end of the book without cracking up.

I think the basic reason romance writers (and readers) prefer flawed to damaged is that our books tend to follow a rising story arc. We want our heroines (and heroes) to get stronger as they go. To recover. To grow. Basically, we want them to be better people at the end of the book than they were at the beginning. I worked with that idea with Long Time Gone–Erik was flawed, certainly, but he was better by the end of the book. Damaged characters can't do that—once broken, they're not likely to be healed in any real sense.

I don't dislike books with damaged heroines or heroes, but I don't necessarily seek them out either. At the end of The Cheater, I didn't have any high hopes for Lily Forrester to become a more together person. She got through one dangerous situation, and she may be able to repair some of the damage to her life, but she's never going to be whole. Overall, I have to admit, I sort of prefer the kind of thrillers written by somebody like Elizabeth Lowell, which are basically romances in thriller mode with a more-or-less romantic endings. And that's fine with me. I don't want to have to worry about who's going to pick up the pieces after the novel ends.

July 30, 2010

Meanwhile Back At the Ranch

When you write a series, you have one major problem that has to be dealt with—filling in the blanks for people who may not have read the earlier books. Authors who have long-running series are usually pretty straight-forward about this. Ed McBain always used to begin his 87th Precinct books with a quick run-down of any character traits you needed to know about in order to understand what was going on. After a while, I knew enough to skip over the descriptions of Meyer Meyer (who, we learned in every book, was bald as a cue ball) and the information about Teddy Carella being both gorgeous and deaf. Similarly, Linda Fairstein always includes a quick recap about Mike Chapman's dead fiancée and the fact that Alex Cooper is a wealthy woman courtesy of her father's surgical invention. That way if you pick up an Alexandra Cooper mystery for the first time, you're oriented without having to read any of the other books to catch up.

When you write a series, you have one major problem that has to be dealt with—filling in the blanks for people who may not have read the earlier books. Authors who have long-running series are usually pretty straight-forward about this. Ed McBain always used to begin his 87th Precinct books with a quick run-down of any character traits you needed to know about in order to understand what was going on. After a while, I knew enough to skip over the descriptions of Meyer Meyer (who, we learned in every book, was bald as a cue ball) and the information about Teddy Carella being both gorgeous and deaf. Similarly, Linda Fairstein always includes a quick recap about Mike Chapman's dead fiancée and the fact that Alex Cooper is a wealthy woman courtesy of her father's surgical invention. That way if you pick up an Alexandra Cooper mystery for the first time, you're oriented without having to read any of the other books to catch up.

I haven't had quite as much to summarize in my Konigsburg books, but I've done a bit. Long Time Gone has perhaps a bit more than my other books because I needed to make sure readers understood Erik's background and what he was trying to overcome. Some of that background had been mentioned in earlier books, but this was the first time I'd gone into it in depth.

The thing is, all of my books are self-contained: the story begins and ends within the book itself, although there may be passing references to occurrences in the other books. That's why I can quite honestly say that I don't think it matters which book you start off with, although there's obviously an order in which the books take place. You don't need to read Venus In Blue Jeans to understand Wedding Bell Blues, although you may want to go back later to find out exactly how Cal and Docia met and fell in love. I think of this as similar to the way Stephanie Laurens runs her Cynster books. No matter where you start in the series, you'll be okay. But you may eventually want to go back to the beginning.

I was thinking about this the other day as I read Carla Neggers's newest book, The Whisper. I love Neggers's stuff, and I think I've actually read almost everything she's written. But the task she has is a lot tougher than the task I have. Neggers has a continuing story that's carried forward in The Whisper. It relates most immediately to the book that preceded it, The Mist, but there are also lots of references to the book that preceded The Mist, The Angel. And some of the characters date back to the first book in the series, The Widow. Now I've read all of these books, and I read them in order. But The Widow came out in 2006, and by now I don't remember all the details or all the character names. In fact, truth be known, I don't really remember the details from The Mist, and it came out last year. Thus Neggers needs to remind me of the necessary plot points along with setting up new readers who've never encountered these people before. She does it successfully, I think, but you have to hold on and keep going through a lot of characters doing a lot of somewhat mysterious things before the story begins to pull together. Neggers isn't the only one who has to deal with this. Kay Hooper is up against the same problem in her paranormal thriller series, and Laurell Hamilton's Merry Gentry books depend on some understanding of what's gone before in order to understand what's happening now.

Besides being tough to do, this kind of series also has a danger that I don't have to deal with. According to one book buyer I talked to, some readers won't buy a continuing series until all the books have been published. They don't want to commit themselves until all the books are available. Then they'll read the series straight through, assuming they remember that the series exists!

So even though the sort of "epic sweep" of a continuing series has its appeal, I think I'll stick with what I'm doing now. After all, it's hard enough to keep track of the characters and events in my limited Konigsburg world. I'd hate to think what it would be like if I had to figure out what was going to happen three books from now!

July 16, 2010

Rules Are[n't] Rules

Recently, I sent a chapter to my critique group from a new MS I'm working on, an urban fantasy. I knew it was rough, and I needed some outside opinions. I got a lot of good advice from a couple of critique partners, but I found myself automatically rejecting the advice I received from the third. Her first comment was that I had a lot of narrative at the beginning of the chapter (true) and that her editor had told her she should never have more than three pages of narrative in a romance.

Now there are a lot of responses to that. One is to say, "You mean three pages of Courier New double-spaced or three pages as they'd appear in the actual print edition, which would be more like five pages of Courier New double-spaced?" Another would be to look at a couple of romance writers to see if it was true (I checked the Nora Roberts I was reading at the time and immediately stumbled over five pages of narrative relatively early in the book). But realistically, I knew the thing that had set me off was the idea that there was some kind of absolute rule for the length of narrative. Had the critiquer said, "Boy you've got a lot of narrative here—I'm getting lost and/or bored," I probably would have gone back to the MS and looked more critically at the passage. But something about the idea of a rule about how much narrative is enough based solely on number of pages rather than quality of narrative just rubs me the wrong way.

I feel the same way about a lot of "rules" that people cite with romances. For example, "The hero and heroine have to meet within the first ten pages." Now the idea that the hero and heroine need to be introduced fairly soon, like within the first couple of chapters, makes sense. But the idea that they have to meet and meet quickly is just nonsense unless you're writing a category romance with a very stiff set of rules provided by the publisher. If you don't believe me, check the romances on your shelf. I'd be willing to bet that a significant number of them don't have hero and heroine meeting within the first ten pages. The "No adultery" rule is another one that writers continually dance around. In Roberts' Dancing On Air, for example, the heroine is an abused wife who's faked her own death to escape her homicidal husband. Technically, she's committing adultery with the hero, but I doubt any reader holds it against her.

The only romance rule that seems absolutely unquestionable is HEA. But even here, writers like Nicholas Sparks seem to slide by occasionally. Of course, he's also dismissed by a lot of romance readers as not really writing romance. I tend to agree with that assessment.

The bottom line is this: if you, as a critiquer, don't like something in my MS, fine. Tell me so, and tell me why. I may wince (and I may call you names, but since most of my critiquing is on-line, you won't hear them). But don't claim that my stuff is bad because I'm violating some kind of cockamamie rule. Rule or not, the problem is that you don't like what I'm doing. I need to know that and I need to know why you don't like it. Then I can either fix it or not, depending on whether I think it's a legitimate complaint. But trust me, if you try to hide behind an artificial rule, I can guarantee I'll ignore you.

July 1, 2010

Wine Festivals, Long Time Gone, and Me

My fourth Konigsburg book, Long Time Gone, releases next Tuesday (contests and prizes will be forthcoming). It's Erik Toleffson's story, but it's also Morgan Barrett's story. Morgan is manager of a winery outside Konigsburg. As I've explained elsewhere, Texas is a big wine-producing state, and the Hill Country is one of the major wine regions. Long Time Gone closes with a wine festival, which is actually pretty typical. Texas is full of wine festivals year-round, but the festival in Long Time Gone may remind Texas wine drinkers of one in particular: the Fredericksburg Food and Wine Fest. Fredericksburg, for those who aren't familiar with the area, is pretty much Hill Country Central. It's an old town, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century and founded by German immigrants. Although wine production has spread throughout Texas at this point, there are still a bumper crop of vineyards and wineries in the Fredericksburg area, as well as some famous peach orchards.

My fourth Konigsburg book, Long Time Gone, releases next Tuesday (contests and prizes will be forthcoming). It's Erik Toleffson's story, but it's also Morgan Barrett's story. Morgan is manager of a winery outside Konigsburg. As I've explained elsewhere, Texas is a big wine-producing state, and the Hill Country is one of the major wine regions. Long Time Gone closes with a wine festival, which is actually pretty typical. Texas is full of wine festivals year-round, but the festival in Long Time Gone may remind Texas wine drinkers of one in particular: the Fredericksburg Food and Wine Fest. Fredericksburg, for those who aren't familiar with the area, is pretty much Hill Country Central. It's an old town, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century and founded by German immigrants. Although wine production has spread throughout Texas at this point, there are still a bumper crop of vineyards and wineries in the Fredericksburg area, as well as some famous peach orchards.

Every fall Fredericksburg holds its wine festival, usually in October. Those in northern climes (like me) might consider that a bit risky—I mean we had a couple of feet of snow here on the Front Range last October. But in South Texas, October is the month when things finally begin to cool down a little. Which means that the Fredericksburg festival is a lot more comfortable than the Austin festival in May or the famous Grapevine festival in September, both of which tend to be blistering.

The Food and Wine Fest is held in the Fredericksburg city park, which also is well set up for festivals and arts and crafts shows. Here's how I described the wine pavilion in Long Time Gone:

The Food and Wine Fest is held in the Fredericksburg city park, which also is well set up for festivals and arts and crafts shows. Here's how I described the wine pavilion in Long Time Gone:

Around noon, Erik took a quick tour around the perimeter of the city park. All three pavilions were in use. The largest had the winery booths. The varicolored silk banners dangled over each one, with the winery's name and logo. Across the front of the building was a table with the silent auction baskets full of wine bottles and gift-wrapped boxes with floppy ribbons. Hostesses from the Konigsburg Merchants Association milled around, dressed in cowboy hats and vests that made them look like waitresses in a kiddy restaurant.

That is, I assure you, what the winery pavilion looks like in Fredericksburg, too. The other thing I stole from the Food and Wine Fest is the music. Bands play in their own small pavilion with an eclectic variety of musicians. The DH and I even caught the amazing Joel Guzman, accordionist extraordinaire, playing electric organ for one group.

That is, I assure you, what the winery pavilion looks like in Fredericksburg, too. The other thing I stole from the Food and Wine Fest is the music. Bands play in their own small pavilion with an eclectic variety of musicians. The DH and I even caught the amazing Joel Guzman, accordionist extraordinaire, playing electric organ for one group.

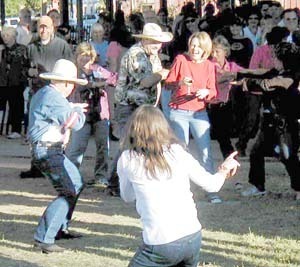

However, for the several years we attended, the headliner was always the same: the legendary Ponty Bone and his band. Ponty played with the Texas Tornadoes among others, and his brand of music combines Tejano and Cajun in a kind of seamless blend.

I also borrowed the idea of the "dance leader" from reality. I have no idea who this guy was, but he always led the line dances whenever Ponty got going, and he could be pretty nasty to anyone who didn't get up and follow him, particularly non-dancing people like me who wanted to take his picture. Never mind. I revenged myself by making him an eighty-year-old banker in a Hawaiian shirt in Long Time Gone. So there.

I also borrowed the idea of the "dance leader" from reality. I have no idea who this guy was, but he always led the line dances whenever Ponty got going, and he could be pretty nasty to anyone who didn't get up and follow him, particularly non-dancing people like me who wanted to take his picture. Never mind. I revenged myself by making him an eighty-year-old banker in a Hawaiian shirt in Long Time Gone. So there.

So anyway, thank you Fredericksburg for providing me with so much material. And thank you all for reading my Konigsburg books. Long Time Gone will be available from Samhain Publishing starting July 6.

And now, a bonus. All who comment here will be entered in a drawing for a free copy of Long Time Gone when it releases on Tuesday. Let the comments begin!

June 18, 2010

Bitch, Bitch, Bitch

In a recent film review, one critic pointed out that a particular movie had all the standard rom com elements, including the fact that the hero and heroine spent the first third of the movie bickering. That sort of startled me, because it's absolutely true. Think about it—just about every romantic comedy of the last couple of years begins with instant dislike. The heroine thinks the hero's a clod. The hero thinks the heroine's a snotty bitch. They trade wisecracks and dirty looks until some outside force throws them together and forces them to re-evaluate each other. This, in turn, made me stop and think—why is this true? Why must rom coms all begin with the couple disliking each other?

I suppose on the one hand we could blame When Harry Met Sally, which is sort of the standard for the contemporary rom com. Harry and Sally are famously antagonistic at first, but what makes them come around isn't any outside force, it's maturity: they both grow out of their earlier prickliness. And when they start fighting again, it's over something serious—the fact that their friendship has moved into love and they're both freaked out about it. Most current rom coms feature bickering for no particular reason. And in many cases both hero and heroine are absolutely right: he is a clod and she is a snotty bitch, neither of whom you feel like spending a lot of time around.

So why can't we have a hero and heroine who are instantly attracted rather than annoyed? Well, one might argue, you need some kind of conflict and being attracted to each other doesn't allow for that. But the external force that acts to keep the lovers apart could be the source of that conflict rather than antagonism. In Four Weddings and a Funeral, hero and heroine are immediately smitten, but her commitment to another man keeps them apart. In The American President, it's his job (i.e., being POTUS) that makes their romance unworkable. In Victor/Victoria, it's her job (i.e., being, well, Victor/Victoria). In Bull Durham, it's her neurosis (sorry, but she's a nutcase) and the fact that, once committed to Nuke, she's sort of stuck. In The Holiday, both heroines are only in place for a short time and feel they can't really commit themselves because of that. In the Colin Firth story-line of Love, Actually it's the fact that he doesn't speak Portuguese.

My point is that hero and heroine don't have to be obnoxious jerks to have a rom com with bite. It's possible to have obstacles even if hero and heroine are both likeable and attracted to one another. Unfortunately, those obstacles can also be insurmountable (see 500 Days of Summer and Annie Hall). The problem, as I see it, comes down to laziness. It's so much easier to begin with heroes and heroines who snipe at each other since that's the kind of groove rom coms have fallen into.

On the other hand, how many of these formulaic rom coms have been successful lately? Wouldn't it be easier if just once Kate Hudson or Jennifer Anniston could fall for the guy right out of the starting gate instead of spending thirty minutes being snippy? If they did, maybe we'd all be more willing to go see these movies than we are at the moment. I know I would!