Y.S. Lee's Blog, page 5

April 12, 2016

Circling back

Last night, I realized that we forgot to introduce our 7yo to fairy tales and fables. No Hans Christian Andersen. No Brothers Grimm. No Aesop. No Monkey God, from the Chinese tradition. No Coyote, from indigenous traditions. No Disney versions, even.

Exception: the summer he was 2, we took a roadtrip and he was so fussy and tearful that I spent the entire trip facing backwards (from the front passenger seat), telling him either “The Three Little Pigs” or “Goldilocks”, over and over and over. I’d have branched out but every time I tried to tell a third story, he began screaming again. Apart from “The Three Little Pigs” and “Goldilocks”, our firstborn is a blank slate for fairy tales.

I think I remember how this happened. I wanted to hold off on the Disney adaptations until he’d encountered the originals and visualized them for himself. And each time I looked up translations of Grimm and Andersen at the library, the stories just seemed too old for him. Dark. Violent. Cynical.

At this point, however, our 7yo has already encountered the Second World War and the Holocaust. He’s asked what the F-word is (and I’ve told him). And sometimes, to express extreme self-pity, he deliberately stands like the Wimpy Kid. “Hey, Greg Heffley,” we greet him in passing. Basically, I think we’re ready to circle back. Here’s what I’ve ordered up from the library:

At this point, however, our 7yo has already encountered the Second World War and the Holocaust. He’s asked what the F-word is (and I’ve told him). And sometimes, to express extreme self-pity, he deliberately stands like the Wimpy Kid. “Hey, Greg Heffley,” we greet him in passing. Basically, I think we’re ready to circle back. Here’s what I’ve ordered up from the library:

The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, ed. Noel Daniel, trans. Matthew R. Price (Taschen)

I couldn’t decide which of these translations of Hans Christian Andersen to choose, so I’ve requested both (yay, libraries!)

The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen, trans. Jeffrey Frank and Diana Crone Frank (Granta).

Fairy Tales, by Hans Christian Andersen, trans. Tiina Nunnally (Viking). I love Nunnally’s recent translation of Pippi Longstocking, so I have high hopes for this one.

I’m still searching for the right edition of Wu Cheng En’s Journey to the West, a classical Chinese novel about the adventures of the greedy, sneaky, impulsive Monkey God. My local library holds a bunch of these graphic novel versions, retold by Wei Dong Chen and illustrated by Chao Peng, which I’ll investigate.

I’ll also keep looking for well-illustrated versions of the Arthur Waley translation. I have extremely fond memories of my grandfather reading these stories to my brother and me, translating from Chinese as he went, so I’m hoping to find a really exceptional edition.

I haven’t yet tackled Aesop or researched First Nations mythology, but I’ll get there. Do you have any recommendations? Strong convictions about fairy tales? Lay it on me in the comments, please!

April 5, 2016

Keep going, never end

Hello, friends! A couple of months ago I was browsing our local indie bookshop and noticed that William Boyd has a new novel out. As you might know, I’m a longtime fan of his and I immediately bought the book. When I got home, I was startled to discover that it’s called Sweet Caress. Um. It’s a good thing I’m already a superfan, otherwise I definitely wouldn’t have glanced twice, let alone plucked it from the shelf.

Hello, friends! A couple of months ago I was browsing our local indie bookshop and noticed that William Boyd has a new novel out. As you might know, I’m a longtime fan of his and I immediately bought the book. When I got home, I was startled to discover that it’s called Sweet Caress. Um. It’s a good thing I’m already a superfan, otherwise I definitely wouldn’t have glanced twice, let alone plucked it from the shelf.

That’s a terrible shame because I’m enjoying it so much. Boyd is working mostly in familiar terrain (England and New York in the twentieth century, special emphasis on the Second World War) and in his usual narrative style (alternating strands of narrative from different time periods). Yet the effect is startling.

His protagonist, Amory Clay, is a female professional photographer born in 1908. She’s the female counterpart to Logan Mountstuart, the protagonist of Boyd’s Any Human Heart, but although Boyd is retreading the scenes of Logan’s life here (boarding school, creative career, London, New York, the War, its aftermath), Amory is far more vulnerable – literally so – because of her sex. Her life is messy, unconventional and gripping.

There are a few things that don’t quite ring true for me about Amory, but there are far more that do. Some of them make me sit back and wonder, How does Boyd know this? For example, here’s the sixty-nine-year-old Amory having lunch with a thirty-something diplomat:

Within about two minutes I knew I didn’t like him – not because of his manifest intelligence but because he was one of those men who cannot conceal their sexual interest – their sexual curiosity – about any and every woman they encounter… Here I was, sixty-nine years old, chatting away, as this young man’s querying lust, his snouty evaluation, first assessed and then casually rejected me. Maybe all men do this – instinctively consider the sexual potential of every woman they meet. I can’t say – but all the men I’ve known have taken care to conceal it from you, if you’re a woman, unless that encounter is taking place expressly with some sexual end in mind, of course.

The young waitress comes to their table and

I sensed Alisdair McLennan’s idle carnal interest now play over her as she stood there, taking our orders, like an invisible torch beam, probing, considering, and then being switched off. Nothing doing. As a consequence, I became a bit dry with him, a bit clipped and cynical, as if to say: I’ve got your number, my friend – and it doesn’t appeal. But I don’t think he picked up the nuances – these kind of men don’t. It’s a variant version of pure ego – they’re never aware how others are judging them.

To me, that’s an remarkable bit of insight. Astral projection, even. The phrase “snouty evaluation” especially got to me: the way it evokes uncouth nosing and nudging is perfection.

Because Amory is a photographer, the book is decorated with “found” period photographs. I’m really ambivalent about this. It’s a lovely idea but with very few exceptions, I find the photos disappointing – particularly those that are supposed to represent Amory’s professional work.

This one, meant to be of Amory, her younger sister and her father, is my favourite so far.

This one, meant to be of Amory, her younger sister and her father, is my favourite so far.Others, though, are just delightful – like this one. And of course the father’s handstands become an important part of the story.

I’m only two-thirds of the way through Sweet Caress (really, I hate even typing the title) and am trying not to anticipate too much, although Boyd is shameless about dropping hints (wedding day, Vietnam, a missing brother) of what’s to come. It’s a classic Boyd experience for me because despite its flaws, I want it to last forever. Reading it hurts a little because each page brings me closer to the end.

That might be the best thing I could possibly say about a book.

March 29, 2016

Welcome, spring

Hello, friends. It’s early spring in eastern Ontario. This means that everything – everything! – is brown, there’s salt and grit all over the sidewalks and roads, and the weather is still mostly wintry. If T. S. Eliot had lived here, he would absolutely, positively have declared that March, not April, is the cruellest month.

Despite this, we had a lovely, lazy long weekend. Dinner with neighbours. An Easter brunch tradition with friends. And we started some seeds in seedling trays: butternut and acorn squash, sugar pumpkin, kale, eggplant, watermelon, peppers, basil chrysanthemums, and as many tomato varieties as we could find. It’s only through rituals like these that I begin to have confidence that spring will actually arrive.

And then: look what the wind blew into our garden!

Tattered and miraculous and imperfect and awe-inspiring.

Thank you. I needed that.

March 22, 2016

Writers for Hope

Hello, friends. This week, I’d like to spread the word about Writers for Hope, an online auction to benefit RAINN (the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network). Writers for Hope began in 2014 and more than doubled its funds raised in 2015. Its organizer, Kelly Johnson, ensures that 100% of the money goes directly to RAINN.

This year, there are more auction items – 96! – than ever. They include query, chapter, and full manuscript critiques from agents and authors, including a first-chapter critique from me. Also on offer: consultation calls, developmental editing, and a whack of books. Yes, “whack” is the collective noun for a pile of almost 50 books.

The auction goes live on April 4. If you’d like to bid, I recommend browsing the auction items ahead of time and plotting your bidding strategy accordingly. And I’d love it if you signal-boosted the event in any way. The hashtag is #WritersForHope.

Thank you!

March 15, 2016

Holocaust literature for younger children

“Who was Hitler?” asked my seven-year-old, a couple of weeks ago. It was 7.30 on a weekend morning.

It turns out he’d been inspecting the books on my desk. I ought to have seen this coming: I’ve amassed heaps of primary and secondary sources about the Second World War over the past three years. It just never dawned on me that he’d go browsing through the unglamorous adult books in the study when there are so many age-appropriate books for him in nearly every other room of the house.

Over the past two weeks, taking my cues from S’s direct questions, we’ve spent quite a few hours talking about race, racism, Hitler, war, conscience and resistance. It’s been hard: the most complicated, painful thing I’ve had to explain to him thus far. When I defined racism his first response was, “That’s rude.” He was so innocent that he didn’t have the vocabulary for talking about hate. I had to correct him: “No, that’s evil.” Yet he’s capable of morally complex questions, among them: “Why do people go to war?”, “Why did Hitler believe what he did?” and “What would you have done if you lived in Germany and Hitler said you had to be a soldier?”

S’s questions also uncovered a cultural fault line in our house. Nick grew up in 1970s/80s England. When he thinks of Hitler, he thinks about the Battle of Britain, rationing, conscription. For him, the war is recent and local and deeply personal. Because I grew up in Canada, Hitler means the Holocaust, the Jewish diaspora and the Allied war effort. For me, the war is frightening but also distinctly historical, definitely elsewhere. S’s three-word question has really underscored for me that while our children are biracial, they are also inheriting (at least) three cultures.

We will get to the Battle of Britain and British military history. We will also get to the Pacific War. But for now, our first priority is to introduce the Holocaust without too many nightmares, both literal and figurative.

When I began looking for children’s books about the Holocaust, most seemed written for middle-grade or young adult readers. I wasn’t even sure there existed such a thing as Holocaust literature for younger children. It was only when I began asking, not googling, that titles began to pop up (hurray for people, not search engines!). The list below is drawn from the generous, well-read brains of bookseller Rachel E. L. King, librarians Eugenia Beh and Paige McGeorge, authors Robin Stevenson and Jill Bryant, book blogger Rebecca Herman, my aunt Cynthia Krause, and a couple of Facebook friends who like to keep a low profile.

Here’s a list of picture-book titles thus far. Titles with asterisks are the ones I’ve read, thanks to the Kingston public library, and for those I include my notes in italics.

Picture books about the Holocaust

*Adams, Simon. World War II (Dorling Kindersley Eyewitness series). Straight-up military history with excellent photographs. Middle-grade. Will save for a couple of years.

*Borden, Louise and Allan Drummond. The Journey That Saved Curious George: The True Wartime Escape of Margret & H. A. Rey. Primarily for committed fans of the Reys. The story is diffuse and children will need a firm grasp of the events of the War in order to make sense of how the Reys’ journeys fit into it.

Bunting, Eve. Terrible Things: An Allegory of the Holocaust.

Deedy, Carmen Agra and Henri Sorenson. The Yellow Star: The Legend of King Christian X of Denmark.

Elvgren, Jennifer and Fabio Santomauro. The Whispering Town.

Hesse, Karen and Wendy Watson. The Cats in Krasinki Square.

Johnston, Tony and Ron Mazellan. The Harmonica.

*Kacer, Kathy and Gillian Newland. The Magician of Auschwitz. Based on a true story. Ideally, readers will have a solid understanding of the Holocaust and concentration camps before beginning this book.

Mochizuki, Ken and Dom Lee. Passage to Freedom: The Sugihara Story.

Oppenheim, Shulamith Levy and Ronald Himler. The Lily Cupboard: A Story of the Holocaust.

*Polacco, Patricia. The Butterfly. An effective introduction to the Resistance. Heavy-handed at times.

Rappaport, Doreen and Emily Arnold McCully. The Secret Seder.

*Rubin, Susan Goldman and Bill Farnsworth. Irena Sendler and the Children of the Warsaw Ghetto. A deft and suitably complex introduction to the concepts of the Holocaust and the Resistance, and my first choice to read with my son. The diction is high and a seven-year-old will need help understanding the ramifications of some statements.

*Ruelle, Karen Gray and Deborah Durland Desaix. The Grand Mosque of Paris: A Story of How Muslims Rescued Jews During the Holocaust. I had very high hopes but was ultimately disappointed by how fragmentary and unverifiable most of the anecdotes were in this book. Again, the diction is too high for the average picture-book reader.

*Spielman, Gloria and Manon Gauthier. Marcel Marceau: L’enfance d’un mime. Originally published in English as Marcel Marceau: Master of Mime. I read the French edition, so cannot comment on the English text. A sound introduction to the Resistance through the framework of Marceau’s early life.

*Tryszynska-Frederick, Luba, Michelle R. McCann and Ann Marshall. Luba: The Angel of Bergen-Belsen. A powerful story that requires a sound understanding of the War and concentration camps to be comprehensible. Includes many quotations from Luba Tryszynska-Frederick, which are less effective for children because of how formal her language is.

*Ungerer, Tomi. Otto: The Autobiography of a Teddy Bear. A nice conceit, but odd to my eyes because it places the German Aryan boy’s experiences at the centre of the story. The illustrations depict a black American soldier as deeply simian. Can’t recommend this one.

*Upjohn, Rebecca and Renné Benoit. The Secret of the Village Fool. Based on the true story of a village outcast who sheltered a family in his root cellar. Simple and moving, with a lovely coda about the family members who survived the war.

Wiviott, Meg and Josee Bisaillon. Benno and the Night of Broken Glass.

This list is a work-in-progress and I’m still reading. If you have picture-book recommendations for me, please do leave them in the comments. And thank you!

March 8, 2016

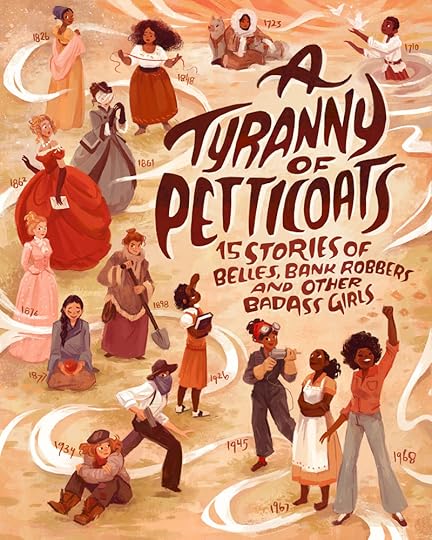

A Tyranny of Petticoats

Happy book birthday to Jessica Spotswood, whose kickass anthology, A Tyranny of Petticoats, went on sale yesterday! Here’s to piracy, stunt flight, revolution, exploration, gold-panning, fortune-telling, and so much more in these fifteen short stories about girls in American history. Was it coincidence that yesterday was International Women’s Day? I think not.

From an impressive sisterhood of YA writers comes an edge-of-your-seat anthology of historical fiction and fantasy featuring a diverse array of daring heroines.

Criss-cross America — on dogsleds and ships, stagecoaches and trains — from pirate ships off the coast of the Carolinas to the peace, love, and protests of 1960s Chicago. Join fifteen of today’s most talented writers of young adult literature on a thrill ride through history with American girls charting their own course. They are monsters and mediums, bodyguards and barkeeps, screenwriters and schoolteachers, heiresses and hobos. They’re making their own way in often-hostile lands, using every weapon in their arsenals, facing down murderers and marriage proposals. And they all have a story to tell.

With stories by:

J. Anderson Coats

Andrea Cremer

Y. S. Lee

Katherine Longshore

Marie Lu

Kekla Magoon

Marissa Meyer

Saundra Mitchell

Beth Revis

Caroline Richmond

Lindsay Smith

Jessica Spotswood

Robin Talley

Leslye Walton

Elizabeth Wein

And, as my friend Viv blessed us on International Women’s Day, “May you all run everywhere without getting verbally and physically harassed ever (and may harassers spontaneously fall out of cars/bikes and onto sidewalks under the weight of collapsing patriarchy and be trampled on by younger generation of feminist children).”

I’ll raise a glass to that!

March 1, 2016

Leap Day Magic

On Leap Day, I went ice skating for the very first time*. It was unexpectedly magical.

Ice skating is something I’ve wanted to try for ages but it took me a while (okay, several years) to get organized. First I had babes-in-arms, then toddlers-on-the-hip, followed by perfectly-capable-children-who-nevertheless-insisted-on-being-carried. And last winter, an acquaintance fell while skating on the Rideau Canal, fractured her forearm, and couldn’t return to work for 8 months (she’s a dental hygienist). That definitely gave me pause.

But this week, the timing was just right. My seven-year-old had a day off school and my four-year-old did not. My son and I walked down to the outdoor rink at Market Square, just the two of us, and laced up in perfect weather: blue skies, sunshine, just cold enough for the ice to stay solid, yet warm enough that we could feel our fingers while tying laces. Then my son stepped onto the ice and said, “This is how you push off, Mummy.”

I wobbled, he giggled, we rested every two laps. Here’s what I learned:

In hockey skates, keep your weight on the balls of your feet. The blades curve under your heel, so if you lean back – or even stand tall – you will fall backwards.

You go faster when gliding than when pushing.

Yoga helps with balance. I was expecting to fall quite a lot, but instead only fell once. Sure, there were several undignified moments of scrabbling/lurching, but mostly I stayed on my feet.

It doesn’t take long at all to feel the magic.

As we were preparing to leave for a hot chocolate, a woman in her late 60s/early 70s stepped onto the ice. She was amazing to watch: swift, serene, each movement small and apparently effortless. And I thought, THAT is what I want. If I work at this, I’ve got another three decades of flying along in the winter sunshine.

The real trick now is making time to skate again before next Leap Day…

How was your week, friends? How did you spend your Leap Day?

*Nick insists that Monday was not technically my first time: apparently, in my twenties, I tried it once but found the skates so uncomfortable that I muttered dark things for the entire ten minutes they were on my feet. I remember nothing.

February 23, 2016

“pungently hostile”

Friends, I have a dilemma. I’m currently reading Christopher Hale’s Massacre in Malaya: Exposing Britain’s My Lai as part of the research towards Monsoon Season. It’s a very compelling book. I haven’t yet got to the part about the Batang Kali Massacre (to which the title refers) but my inter-library loan copy is already feathered with post-it notes.

I am very keen to see how his argument develops (Neal Ascherson describes it as “a pungently hostile history of British colonial strategy and tactics in the region”) and I admire Hale’s gift for historical precis. But there’s a problem.

Less than halfway through the book, there have been a completely distracting number of mistakes. Many of them are small things that a copy editor ought to have caught:

Some Asian names appear with variant spellings: Giya Gun vs Giyu Gun (the latter is correct).

Spencer Chapman vs. Chapman (trickier, but the latter is correct).

Malayan Communist Party leader Chin Peng is listed in the bibliography as “Peng Chin”. It’s a nom de guerre but even so, the false family name should still be cited as “Chin”.

Others mistakes are larger and thus very embarrassing. For example, Hale mentions “the elderly Madam Cheng Seang Ho… [whose] heroic death fighting at Bukit Timah earned her the title of Malaya’s La Passionaria (after the Spanish communist leader Dolores Ibárruri) (146)”. It’s a magnificent story, marred (or not!) by the fact that Cheng Seang Ho survived the Battle of Bukit Timah. Madam Cheng appears in this Straits Times article of July 25, 1948, yet she seems to have been forgotten even in her own lifetime. This 1957 news story shows her interrupting a ceremony at the Kranji war memorial – a ceremony at which she surely ought to have been honoured. This is a point that actually serves Hale’s larger analysis, yet he’s lost the chance to use it.

Finally, nearly everything goes uncited. Some direct quotations are even unattributed! Neither are there clues to support assertions like, “Rape, belligerent drunkenness, the trashing of shops and stores – this was the face that Tommy turned to the East.” I am willing to believe this sentence; it rings true. But that is a huge bundle of claims to repeat in good faith.

I understand that this book was never intended as a scholarly monograph. In his “Acknowledgements”, Hale calls it “an extended essay rather than a textbook or academic historical study”. Yet I should be able to track things down. I need to know who else was forgotten, what else possibly misreported. If nothing else, I would love to know where so many of Hale’s tantalizing quotations come from. (Somebody apparently said: “If talking about a chip shop in Salford, Churchill would find a way to mention how important its chips were to the Empire.” COME ON, NOW! I think we all want to know who said that.)

So I’m stuck. I am on board with Hale’s argument so far. I can definitely see elements from Massacre in Malaya making it into Monsoon Season. But I’ve seen enough mistakes at this point that I’m on high alert: Are you sure? Is that correct? How can I be sure that’s what was said?

Can you help me out, friends? What do you do when a book is conspicuously flawed and there’s no path to its primary and secondary sources?

February 16, 2016

“The shortfall between the imagined and the real…”

Hello, friends. I might be one of the last adults in the Western world to discover George Saunders but it’s happened at last. I am so glad it has!

In 2008, shortly after I had my son, my dear friends K and A gave me a copy of Saunders’s essay collection, The Braindead Megaphone. The timing was less than ideal. I had a newborn who seemed never to sleep, I was recovering from a complicated and frightening childbirth ordeal, and when I tried to read the first paragraph of the title essay, I could actually feel the exact moment his words bounced off my brain. Also, I hated the cover. It blared at me in just the way Braindead Megaphone Guy blares at everyone, which I realize is the point, but at the time all I wanted to do was burn it. In the end, Nick shelved it somewhere lowdown and easily ignored and I didn’t think of it for eight years.

This past week, I read a very funny and close-to-the-bone short story in the New Yorker and realized, after the fact, that it was by Saunders. It was so good that I ended up poking around the dusty bookshelves near the woodstove and recovering my copy of The Braindead Megaphone. It’s now nine years old and the title essay, which meditates on news coverage of the Iraq War, should be out of date. And yet it’s not. Here’s what I mean:

Our venture in Iraq was a literary failure, by which I mean a failure of imagination. A culture better at imagining richly, three-dimensionally, would have had a greater respect for war than we did, more awareness of the law of unintended consequences, more familiarity with the world’s tendency to throw aggressive energy back at the aggressor in ways he did not expect. A culture capable of imagining complexly is a humble culture. It acts, when it has to act, as late in the game as possible, and as cautiously, because it knows its girth and the tight confines of the china shop it’s blundering into. And it knows that no matter how well-prepared it is – no matter how ruthlessly it has held its projections up to intelligent scrutiny – the place it is headed for is going to be very different from the place it imagined.

This is the sharpest, most compassionate, most acerbic reflection on conflict and culture I’ve read in some time – and I’ve been doing a lot of reading about war and its involutions. I had to sit quietly for a minute, after reading that. And then I turned to the last sentence in the paragraph:

The shortfall between the imagined and the real, multiplied by the violence of one’s intent, equals the evil one will do.

That sentence summarizes, far more eloquently than I ever have, the novel I’m writing right now. It’s something I’ll continue to reflect upon, as I continue my work. And oh, I am grateful to be in the presence of a furious, insightful, spiky, large-hearted thinker such as this.

I’ll probably turn to Saunders’s fiction next. Do you have any particular recommendations?

February 9, 2016

Sisters, scammers, hijinks ensue

Hello, friends! I am still healing from the wisdom tooth extraction and feeling cross about my soup/hummus/pudding subsistence diet. So! Much! Slime! But I don’t want to talk about that. Instead, I’d like to share some of the sources I consulted when writing “The Legendary Garrett Girls”.

As you probably know, I adore research. In this case, though, my research began entirely by accident, with an extended-family holiday to Alaska back in 2007. We rode the White Pass Railway (now a tourist’s toy) and saw the grave of the villainous Soapy Smith, but most of this was secondary. The main impressions I retain from that trip are of the sublime landscape. Still, I bought a souvenir at Parnassus Books (still open! hurray!) in Ketchikan: William B. Haskell’s Two Years in the Klondike and Alaskan Gold Fields, 1896-1898. I flicked through bits of it and then got distracted. I read other books, wrote about other times and places.

Several years later, Jessica Spotswood asked me for a short story for her anthology. Her parameters? “Any time in American history, with a girl protagonist.” Talk about possibilities!

Illustrated timeline by Simini Blocker

I knew I wanted to write about a place I knew, however slightly. (I’m daunted by the idea of a real place I’ve never visited. Even with the internet at my disposal, I question whether I can take the measure of a place without smelling it.) And I’m drawn to people and places on the margins. Alaska was logical, the Gold Rush almost too obvious. But what kind of story was this going to be?

What happened next was Fate. I opened Haskell’s memoir and my eye fell on this line: “They now say there are more liars to the square inch in Alaska than any place in the world.” And that was it: I knew I had to write a romp about con artists during the Gold Rush.

Of course, there were logistics to work out, questions to answer. But unlike my novels, “The Legendary Garrett Girls” has remained remarkably true to its initial proposal, a high-energy scrawl of words on a page: sisters, scammers, hijinks ensue. I hope I’ve got the setting mostly, nearly right. I hope Alaskans don’t shake their heads with pity for the presumptuous cheechako who had the nerve to set a short story in their place, their legendary time. As ever, all errors in the story are my responsibility.

Publishing on March 8!

If you’re as entranced by the Gold Rush as I became, here’s a list of the books that I found most enjoyable – and, in some cases, infuriating but essential.

The Legendary Garrett Girls: Sources

Berton, Pierre. Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899. 1972.

Emmons, George Thornton. The Tlingit Indians. Ed. Frederica de Laguna. 1991.

Haskell, William B. Two Years in the Klondike and Alaskan Gold Fields, 1896-1898. (1898.) 1998.

Hitchcock, Mary E. Two Women in the Klondike. (1899.) 2006.

Holder Spude, Catherine. “That Fiend in Hell”: Soapy Smith in Legend. 2012.

Smith, Jeff. Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel. Klondike Research, 2009.

Winslow, Kathryn. Big Pan-Out. New York: W. W. Norton, 1951.

In a couple of weeks, I’ll return to the question of my sources and talk about anti-heroes, historiography, and holdouts.