Gregory Crouch's Blog, page 24

June 13, 2013

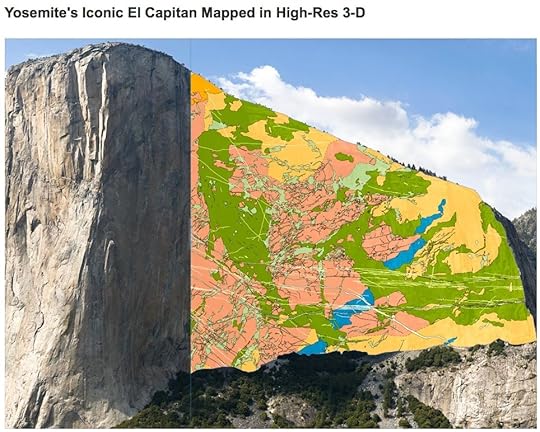

Gorgeous hi-res geologic map of Yosemite’s El Capitan

Here’s an interesting article about the gorgeous geologic map of Yosemite’s El Capitan produced by Roger Putnam, a veteran Yosemite climber and master’s candidate at the University of North Carolina.

June 12, 2013

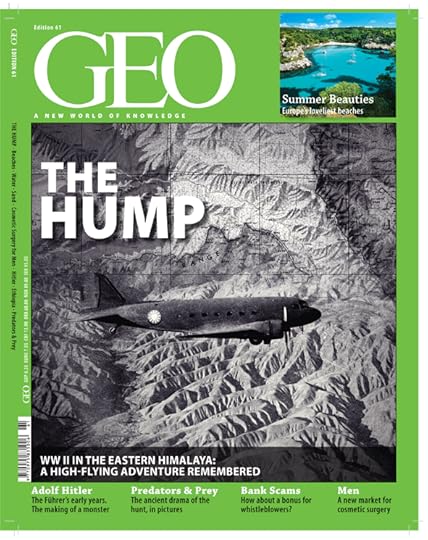

GEO Magazine covers the Hump — CNAC, ATC, Moon Chin, Joe Rosbert, and No. 58′s crash

I’m happy to announce that the June issue of GEO magazine has my article about the Hump Airlift on its cover — a great platform from which to stump for China’s Wings and laud the pioneering efforts of William Langhorne Bond and the China National Aviation Corporation.

I haven’t yet held a hard copy of the magazine, but it’s available electronically by installing the GEO App on your tablet or smartphone and then buying the issue. (The app is free: here’s the link for Apple devices, and here’s the Android link.) I’m truly chuffed with the eArticle, and it has a bunch of enhancements, including a great World War II newsreel about the Hump operation.

I haven’t yet held a hard copy of the magazine, but it’s available electronically by installing the GEO App on your tablet or smartphone and then buying the issue. (The app is free: here’s the link for Apple devices, and here’s the Android link.) I’m truly chuffed with the eArticle, and it has a bunch of enhancements, including a great World War II newsreel about the Hump operation.

(Installing the GEO app is free; buying the issue costs $5.99)

Fellow CNAC-enthusiast and GEO editor Kai Friese worked up the piece with me and wrote the excellent companion story In Search of Ship 58 about his expedition to the crash site of CNAC No. 58, the plane in which Joe Rosbert and Ridge Hammell crashed on April 7, 1943, beginning their epic 47-day walkout to civilization. Amazingly, Kai located Mingah Ramat, one of the Mishmi women whose family sheltered Rosbert and Hammell after the crash. Kai’s eArticle enhancements include a video of Mingah Ramat giving her impression Rosbert crawling across the floor of her hut. That scene is one of my favorites in China’s Wings, and it’s mind-boggling to see it reenacted by an eyewitness — and I’m relieved to see that I imagined it correctly.

How Man Wong, President of the China Exploration and Research Society (CERS), wrote the second companion article, The Veteran, about the amazing life of Moon Fun Chin.

I hope you enjoy the stories. The issue also has an interesting article about Adolf Hitler’s youth and rise to power.

It’s also worth installing the app for GEO’s German edition (Apple; Android). Once you’ve installed the app, they offer one free sample issue (with a reddish cover that says ‘WUNDER’). It’s got an astonishing feature of climbers ascending the Roraima Tepui and a flabbergasting 360 degree image taken from the top.

My gratitude to Kai Friese for allowing me to contribute to his Hump project.

June 3, 2013

Video of Shaken, Not Stirred

Eddie Phay posted a 22 minute climber’s-eye video of an ascent of Shaken, Not Stirred on Vimeo. Crazy cool to watch their ascent and have it feel so familiar. Watching it, I felt like I knew exactly where the next stick of the pick was going to land and where the next gear was going in. Also interesting to watch what has changed in climbing since Jim and I made the route’s FA in 1997. (Damn, those axes and screws look good… and so do those gloves.

Here’s my account of making the route’s first ascent with Jim Donini, in May 1997.

June 1, 2013

Color film of New York in 1939

Here’s a wonderful 2:50 minute film made by a French tourist in New York in 1939 — and it’s in color! (Great soundtrack, too.)

Cars, dresses, hats, suspenders, elevated railways, Harlem, and more, it ends with a great pan of the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building from the observation deck of the Rockefeller Center.

William Bond, main character in China’s Wings, spent the first three months of 1939 in the United States, and he went to New York several times to meet with his corporate superiors at Pan Am headquarters — which was in the Chrysler Building. This film shows his exact milieu.

I would imagine those visits included lunch and lunchtime martinis in the Cloud Club, the former speakeasy built under the stainless steel carapace on the top floors of the Chrysler Building.

May 14, 2013

Another Sistine Chapel truth

Another artistic truth etched in the Sistine Chapel ceiling:

“When will it be done?” growled the Pope.

“When it’s finished, [expletive unspoken],” replied Michelangelo.

[A joke cribbed from a manuscript I'm reading.]

The Hindenburg Disaster

Moon Chin, one of China’s Wings main supporting characters, told me about the huge impression seeing the Graf Zeppelin over Baltimore made on him when he was a boy.

Here’s an incredible run of Hindenburg photos published on The Atlantic’s website.

May 8, 2013

Eurasia Ju-52 at Chungking’s Sanhupa Airport

A partnership between Lufthansa and the Nationalist Chinese government, Eurasia Airlines was CNAC’s great commercial rival through the 1930s and early ’40s.

An email correspondent just brought this superb photo to my attention. It shows one of Eurasia’s Ju-52s, and he asked if I thought it was taken at Chungking’s Sanhupa Airport, a cobblestone airport built on a Yangtze sandbar below the city.

I told him that I thought so, but then decided to see if I could figure it out for sure.

Comparing the hills in the background with this photo, which I know was taken at Sanhupa, I think it’s a definite confirmation.

The two hilltops immediately right of the pole in the picture above are an exact match to the two hilltops at the extreme right of the Ju-52 photo.

March 29, 2013

Interviewing Flying Tiger ace and CNAC stalwart Joe Rosbert

Looking back, I knew less than I thought about the story that would become China’s Wings when I sold the proposal in the spring of 2004, but one thing I did recognize was that my immediate priority was interviewing AVG ace and CNAC stalwart Joe Rosbert.

I’d heard other CNAC veterans talking about Rosbert’s scarcely-believable survival at reunions, and I’d read the “Only God Knew the Way” story that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in February, 1944, but because aspects of the Saturday Evening Post version didn’t sit right with my writerly intuition, I wanted to hear it from the man himself. I also knew that Joe Rosbert wasn’t in good health, so as soon as I could fix the details, I flew to Houston to interview him.

[image error]We met in the Omni Hotel in Katy, Texas, and, as usual, I arrived early. I stood up to greet Joe as he shuffled across the lobby on the arm of his son, Bob. He looked very fragile, and it took a long time to get him settled.

Rosbert had volunteered to help China fight the Japanese in the year before Pearl Harbor, when few others Americans were willing, and his gnarled, veined hands that struggled to steady a coffee cup had once gripped the controls of an AVG P-40 as he battled the Japanese in the skies of Asia in the first half of 1942. He joined CNAC when the Flying Tigers disbanded, and he helped pioneer the Hump flying until he crashed into the Himalayas in April, 1943.

And then Joe Rosbert proceeded to lay on me the very best survival story I have heard in my life.

I started writing as soon as I got back to California. Joe and I did a series of follow-up telephone interviews, and when I’d finished my draft, we did several fact-checking sessions over the telephone.

Here’s a photo of Ridge Hammell and Joe after they staggered out of the mountains, 47 days after their crash — long after they’d been given up for dead.

Sadly, we lost Joe Rosbert not long after I’d completed writing his story.

I was very happy to receive an email a few days ago from Joe’s son, Bob, in which he passed along the Omni photos above (I’d never seen them) and also said how much he and his son Cameron, (Joe’s grandson) have enjoyed China’s Wing, and he wrote that he “felt quite honored by the respect you showed toward the patriarch of the Rosbert family. My Father would be very proud of you!”

Bob told me that started one afternoon and read throughout the night until he finished.

(BTW, should you ever want to make a writer feel good — that’s how it’s done.)

March 16, 2013

Gorgeous adventure footage

I’ve been staring in slack-jawed astonishment at this adventure footage from Renan Ozturk, especially at the spectacular scenes in Alaska’s Ruth Gorge that start near the midpoint. Looks to me like those scenes were taken high on the SE Buttress of Mount Dickey, a mountain that makes a cameo appearance on my recent post about the first ascent of Shaken, Not Stirred. The other route that Jim Donini and I did in the Ruth, The Bourbon Bottle Route, doesn’t quite show up in any of the clips, although Mount Bradley, the mountain it is on, does appear two or three times.

Renan’s footage also puts the Ruth into its proper scale, which none of my pictures ever accomplished.

Check out Renan’s short, it’ll be 3:11 of well spent, inspiring time. I used to live in that world. I’d like to get back to it.

March 6, 2013

Shaken, Not Stirred — stories & photos from the first ascent

Amongst a lot of great climbing in the mid- and late- 1990s, my Enduring Patagonia years, Jim Donini and I made the first ascents of what struck me as three truly world-class alpine climbs: in Patagonia we did The Old Smuggler’s Route on the north face of Aguja Poincenot and A Fine Piece on the west pillar of Cerro Pollone, and on the south face of the Mooses Tooth in Alaska’s Ruth Gorge, we did Shaken, Not Stirred. None was cutting edge in terms of difficulty, but all three were incredibly beautiful; Sophia Loren kind of beautiful.

I’ve always been astonished and grateful that we were able to get onto three such marvelous climbs. Recently, I shared pictures and stories from A Fine Piece. Here, I’m going to post about Shaken, Not Stirred.

First, I need to take issue with the story Jim told Joe Puryear, author of the Supertopo guidebook Alaska Climbing, in which Jim waxes poetic about how he and Jack Tackle had always had their eye on the climb that would become Shaken, Not Stirred but had never gotten around to climbing it. I’ve also heard him talk about how we spotted Shaken, Not Stirred from the summit of Mount Bradley, after we climbed The Bourbon Bottle Route.

Hmmmm….. that’s not how I remember it.

(I’m reserving the right to needle Jim here because he’s one of my best friends, definitely the best climbing partner I’ve ever had, and unless your last name is Tackle, Lowe, Bragg, Kennedy, or Engelbach I’m not extending you the same right. Period. Plus, he kinda hurt my poor little feelings.)

So here’s the real story — or, at least, here’s my version of it. Without any concrete objectives, Jim and I flew into the Ruth in May of 1997 with Kent McClannan and Jurgen Grunevald. Jim was familiar with the area thanks to the expeditions he’d made into the Ruth with Jack Tackle, he and I had done The Bourbon Bottle Route on the south face of Mount Bradley the year before, and I had photocopies of all the American Alpine Journal entries pertinent to the Ruth Gorge. Our plan was to fly in there and “take a look around,” “see what we could find,” and “hopefully get up something.”

We started scouting possibilities soon after Paul Roderick of Talkeetna Air Taxi slipped under the cloud layer and dropped us on the Ruth. (I loved flying with Paul, a real kindred spirit.) Kent was partnered with Jurgen, and I was with Jim, but it was Kent and I who went together to scope the enormous and imposing south face of Mount Dickey. We saw nothing attractive, but I thought to set up my camera tripod and take a zoom lens shot of the south face of the Mooses Tooth with the the bottom of Dickey’s southeast buttress in the foreground.

One peek through the lens changed everything.

Here’s the picture:

The Ham and Eggs couloir (first ascended in 1975 by Jon Krakauer, Thomas Davies, and Nate Zinsser) was clearly visible running up the sun/shade line left of the Tooth’s main summit, but what really caught my eye was the other couloir, the one just into the shade between the west and middle summits. It doesn’t show up too well in this scan, but through the camera lens I could see what looked to be a thin runnel of ice running up slightly to the right of the prominent snowfield high in the couloir and then merging into it not too far beneath Englishman’s Col — the high col between the Tooth’s west and middle summits.

The runnel looked viable, and it looked good.

It looked really good.

Looking through the lens, collecting my thoughts and trying to keep calm, I also realized that I had a problem: I was with Kent, and I didn’t want him and Jurgen to scoop the line. Both were good climbers, and given any opportunity, they’d nail it. Which wasn’t lost on me. So I kept quiet, albeit quivering with excitement.

There are two things in this world I’m good at keeping quiet over: things I’m told in confidence and new-route possibilities. (Fifteen years later, I’m still sitting on some good ones.)

Having spotted the Shaken, Not Stirred couloir, I’d sooner the Mooses Tooth fall over than have somebody other than me grab its first ascent.

Back to camp, I whispered to Jim about what I’d seen and threatened violence if he let on. He took a “ski around” and got himself a vantage. He liked what he saw and we organized a sortie.

We left the tent about midnight, climbed the icefall where the Root Canal Glacier tumbles into the Ruth Gorge to the base of the south face of the Mooses Tooth, and started up the route about six a.m. It didn’t take us long to realize that we were onto something really special. A pitch or two of hollow, rotten ice gained a straightforward couloir, and we climbed that for a long way, until it pinched down to the beautiful ice runnel I’d seen from the opposite side of the Ruth.

Here’s a good overview of the route that I found on the web. The coming photos will make more sense if you click on it and bounce back. Plus, you’ll see why it’s such a great climb.

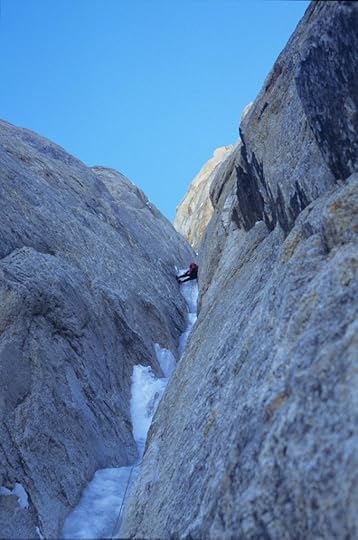

And here’s Jim in an easy part of the couloir. I think he’s about to launch up into the narrow ice runnel.

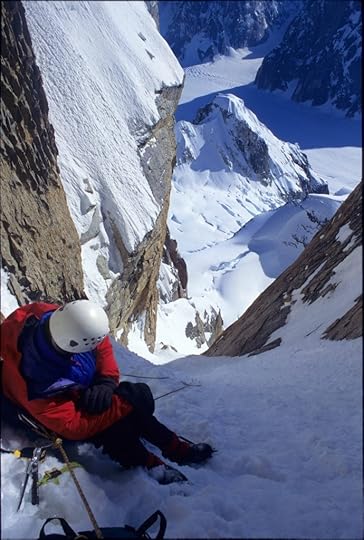

The ice runnel served up the best climbing on the route. Jim got the best of it, and it was fabulous. Below is a shot of Jim copping a rest near the end of a long pitch:

Jim led the bulk of the runnel, which I think went on for four pitches. I got the last one. Here are two pictures of me that Jim took on that pitch (I think):

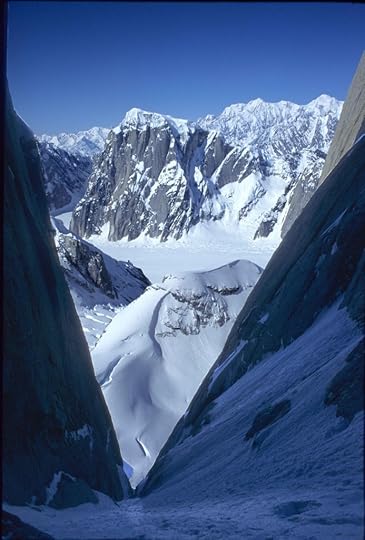

The couloir walls framed spectacular views into the Ruth Gorge. The picture below is an odd converse of the one I’d taken below Mount Dickey the day before, perhaps showing why the route hadn’t been discovered, since only a small slice of the Alaska Range is visible from inside the couloir’s depths.

As I recall, it wasn’t easy to find anchors in the mostly flawless granite beside the snow and ice, but when I did get a stance, I took this picture of Mount Dickey.

A bit farther up, I led the crux of the route, a short, sharp mixed step that wasn’t very well protected. I took off the pack to do it:

I was pretty psyched to get over that step. Above it, I could see that the route would “go” all the way to Englishmen’s Col, and except for a funky move over a snow mushroom that got us back into the main snowfield, it was mostly cruising — in a truly spectacular alpine setting.

Here’s Jim kicking back in Englishman’s Col while we brewed tea.

Jim taking in the sights:

In the other direction, we had an incredible view across the upper north face of the Mooses Tooth, which was holding the day’s last sunshine.

We climbed up and over the west summit of the Mooses Tooth and spent the rest of the night descending to basecamp. Here’s me just after arriving:

Despite two nights without sleep, it didn’t take us long to graduate from hot Tang.

The Shaken, Not Stirred couloir is directly over Jim’s head.

I was delighted. I knew we’d scored a really good first ascent, and it became popular in a hurry, especially once Paul Roderick reduced the approach to five minutes by landing people on the Root Canal Glacier directly below the climb. People with good weather could suddenly knock out both Ham & Eggs and Shaken, Not Stirred in a single weekend.

Here’s what Joe Puryear’s guidebook has to say about Shaken, Not Stirred: “This narrow ice ribbon splitting the immense granite walls of the south face of the Mooses Tooth is an alpinist’s dream. Although it doesn’t provide an easy way to the actual summit, the outstanding nature of the climbing makes it exceptional. And with its easy access and short approach, this is about as good as it gets for Alaskan alpine climbing.”

Makes a guy blush.

As further evidence of my version of the route discovery story, I offer up the phone call I made to Jack Tackle as soon as we were back in civilization: “Dude, how’n the fuck did you miss that?”

Jack wasn’t too happy with my gloating, if I remember correctly (and probably wanted to beat me to a bloody pulp), but at least he had the Elevator Shaft and the Cobra Pillar to ease his pain.

I’d been giving Jim a hard time along those lines ever since we were in Englishman’s Col.

If you’ve got Shaken, Not Stirred stories of your own, please post ‘em or link to ‘em below — along with photos.

Here are good Shaken, Not Stirred photos from Ouray Ice Climbing.

Here’s the American Alpine Journal mention of the second, third, and fourth ascents of Shaken, Not Stirred in 2000, three years after we’d done the first. Kelly Cordes is a friend of mine. I’d forgotten that he’d done the second ascent. Very cool.

Here’s a 22 minute climber’s-eye video of an ascent of Shaken, Not Stirred on Vimeo. I remembered every placement…

On a different topic, please take the time check out the three eStories I’ve just published. They’re only available digitally. However, if you’re NOT normally an eReader, you’ll be able to read them on Amazon’s “Kindle Cloud Reader” or the Barnes & Nobles “Nook for Web,” both of which open in your computer browser. (In my opinion, opening them through Safari on an iPad gives a top-shelf reading experience.)

Here they are:

Into Action is a stark military tragedy that hinges on a young soldier’s struggle to remain loyal to his distant girlfriend in a morally trying, sexually charged situation, and it spotlights the complicated emotional choices shouldered by young men at war.

Into Action is a stark military tragedy that hinges on a young soldier’s struggle to remain loyal to his distant girlfriend in a morally trying, sexually charged situation, and it spotlights the complicated emotional choices shouldered by young men at war.

My first piece of fiction, Into Action is a short story that takes place during Operation Just Cause, the 1989 invasion of Panama, during which I was an infantry platoon leader.

Into Action is available at Kobobooks, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble for $.99.

In 2011, accompanied by National Geographic photographer Stephen Alvarez, I spent a jaw-dropping month climbing the highest mountains in the Islamic Republic of Iran as members of a goodwill exchange between the American Alpine Club and the Alpine Club of Iran, world-class organizations intent on doing something to improve the strained relations between the two peoples. Besides having wild adventures in gorgeous mountains, we built excellent relationships with their Persian hosts, gained a better appreciation of the ancient culture of Iran, and experienced some of the tensions inherent in life in modern Iran, all at a time when the two captured American hikers were still languishing in a Tehran prison.

In 2011, accompanied by National Geographic photographer Stephen Alvarez, I spent a jaw-dropping month climbing the highest mountains in the Islamic Republic of Iran as members of a goodwill exchange between the American Alpine Club and the Alpine Club of Iran, world-class organizations intent on doing something to improve the strained relations between the two peoples. Besides having wild adventures in gorgeous mountains, we built excellent relationships with their Persian hosts, gained a better appreciation of the ancient culture of Iran, and experienced some of the tensions inherent in life in modern Iran, all at a time when the two captured American hikers were still languishing in a Tehran prison.

The Atlantic published a short version in their April, 2012 issue; Rope Diplomacy: On the Steeps in Iran gives you the opportunity to read the full, detailed, and nuanced story accompanied by more than thirty of Stephen’s brilliant photos.

Rope Diplomacy is available at Kobobooks, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble for $.99

Last but not least is Right Mate, Let’s Get On With It, an article that explores the outrageous accomplishments and inner workings of one of the most powerful rope teams in mountaineering history – the partnership of Australian Andrew Lindblade and Kiwi Athol Whimp. Together, they climbed some of the most difficult, dangerous, and beautiful mountains in the world — among them Jannu and Thalay Sagar, vertiginous Himalayan summits that make Mount Everest look like a bump.

Last but not least is Right Mate, Let’s Get On With It, an article that explores the outrageous accomplishments and inner workings of one of the most powerful rope teams in mountaineering history – the partnership of Australian Andrew Lindblade and Kiwi Athol Whimp. Together, they climbed some of the most difficult, dangerous, and beautiful mountains in the world — among them Jannu and Thalay Sagar, vertiginous Himalayan summits that make Mount Everest look like a bump.

Tragically, Athol Whimp died in a fall in the mountains of New Zealand in early 2012. Right Mate, Let’s Get On With It was first published in the June, 2004 issue of Climbing (No. 321), and veteran mountaineer and author Gregory Crouch has updated and eReleased the story in Athol’s honor with Andrew Lindblade’s cooperation and nineteen of his best photos.

Right Mate, Let’s Get On With It is available at Kobobooks, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble for $0.99 (There seem to be issues with Right Mate on Nook, although strangely, not on “Nook for Web.” I’m trying to figure that out.)

And so back to Shaken, Not Stirred…