Ben Peek's Blog, page 17

January 3, 2013

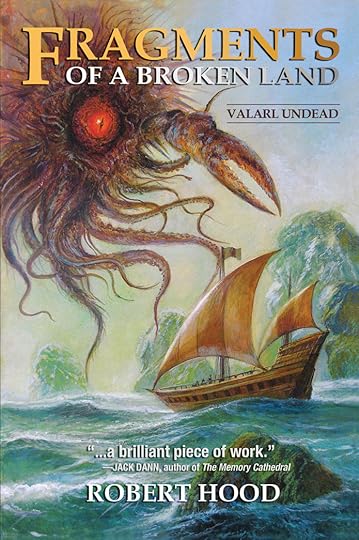

Fragments of a Broken Land

The fine and excellent Rob Hood will have a new book released soon, the long awaited Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead.

To introduce you to the world, and to help get word out about the book, he has put up three stories set in the world, 'Tamed', 'Dark Witness' and 'Garuthgonar and the Abyss'. As I post this, I have read 'Tamed', which I read years ago in the anthology Dreaming Down Under, and which I quite enjoyed--in part, the full realisation of Hood's work, the complete manifestation of his talent. That the complete novel is finally going to be published is nothing short of excellent.

In short, follow the links, check it out, and prepare to its release.

Published on January 03, 2013 19:21

January 2, 2013

Dear Germany

Thank you for buying Black Sheep.

Signed,

Author with Royalty Cheque (Admittedly, A Small One)

Signed,

Author with Royalty Cheque (Admittedly, A Small One)

Published on January 02, 2013 20:02

January 1, 2013

The Hobbit: 48 and 24 Frames Per Second

And so I saw the Hobbit, in both 48 frames per second and 24.

In truth, it is not a film worth seeing twice, but I was curious and, in my life, that's enough to justify anything.

Set before The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit returns Peter Jackson to the director's role on Middle Earth, to tell the story of how Bilbo Baggins found the Ring of Power, met some dwarves, and generally had a bad time of it. Divided into three films, The Hobbit, unlike the previous Lord of the Rings, is a single, slim novel, but the introduction of extra material to help it work as a prequel for its already existing successful films, as well as a cast of thirteen dwarves, pretty much ensures that it would be, at the very least, two, and yes, three films. If you're a big fan of the book, you will probably have issues with that, but from a structural point of view, the film mirrors the opening of the first Lord of the Rings film fairly closely, ending not with the breaking of the fellowship, but rather with the consolidation of this 'new' fellowship. There are times when it could be cut down--indeed, a much leaner, meaner film could have been made by cutting ten of the thirteen dwarves out, as well as various scenes involving storm giants, goblin kings, and more; but then, in all likely, I wouldn't have seen Christopher Lee again, and that, perhaps, is worth it. Still, it is fairly obvious that Jackson wants to mirror his successful first trilogy in terms of structure, thus creating six films that echo across each other, and should that work it will actually be pretty sweet, assuming of course that you can afford to put aside the time to watch them all.

Overall, I thought the film was decent enough, no better nor worse than the first Lord of the Rings film, but there are some disappointing problems with The Hobbit, mostly stemming with a general inconsistency across it. The dwarves, for example, start off looking vaguely decent, with Richard Armitage's Thorin looking, in all honesty, like a Little Viggo Mortensen, or as I like to call him, L'l Vig. From him, however, it's a swift descent into comically designed dwarves who have the misfortune, as one of my friends pointed out, of looking like they are suffering from down syndrome. Since the film cannot accommodate most of the dwarves to have speaking parts or characterisation, they are instead defined by these poorly thought out designs, and these have the unfortunate result of allowing you to think that the minders are taking the downie kids out for the day. But inconsistency is a general problem with the design of the film, from cardboard pumpkins nestled between real sheep and beautifully built CGI cities, to Gandalf's power, which functions as a bad narrative device, revealing itself as all powerful when it is required and less powerful when not, though this last problem has been in all the films and has more to do with Tolkien than with anything else. But still, it remains a problem, and when at the end of the film Gandalf is blowing flame into pine cones to set the first aflame, you can't help but think, 'Dude, didn't you just knock down a billion goblins? Don't you fight a motherfucking Balrog soon enough? Just go down the fireball the shit outta that pale orc.'

So there's that, and it niggles, all the way through.

But what, I hear you say, of the 48 frames vs 24?

Well, that is the reason I saw the film and I saw it first in 48,and it was... awful, frankly.

It looked like a cheap, fan made version of The Hobbit, where somehow Ian McKellen had been kidnapped and forced the reprise his role under threat of losing his toes. For the first thirty minutes, I actually had to fight the urge to get up and leave, telling myself that it would get better--that I would, somehow, adjust to the faster frame rate, but I never did. I wanted to do so: I had paid the money, I had found myself there, and I was keen for a shiny new film toy. But there was never a moment through the entire thing where I thought, 'This looks great.' I always, always thought it looked awful, and I could never allow myself to flow with it. The CGI looked awful. The actors looked both real and unreal, a weird combination of men and women who never quite fit their part. The scenery was uniformly uninspiring. The list goes on, and it goes on in negative ways, resulting in my first opinion being of the film in 48 frames that it was cheap, nasty, and like bad fan work.

There is a lot of conversation out there about it: one article explains that the the frame rate brings in the Uncanny Valley, where things look too real to sustain disbelief. Another points out that it is simply what we, as viewers, have been conditioned to see, and that in time we will adjust to it. There's more, of course, and you can look them but; but personally, I neither know, nor truly care which one is right--the end product is that my reaction to 48 frames is so negative, so very much in the no category that I would not go to pay and watch a film in the faster frame rate, no matter who was responsible.

Whereas, when I saw the film a second time, in 24 frames per second, it was rather like watching a different film. The inconsistencies of set design and dwarves still remained, but Smaug--what you saw of him--did not look truly awful, the actors looked as if they had settled into their characters, and the CGI was overall fine. Of course, that said, in either 48 or 24 frames per second, the storm giant fight in the mountains was awful: poorly designed, poorly conceptualised, poorly everything. But beyond that, the rest of the film looked great, and it looked like a film, like the previous Lord of the Rings films, with beautiful scenery, a fully designed and crafted world that I did not mind spending the time in, and which I was happy to pay money for.

In the end, it is the reaction of the last emotion that justifies whether to use 48 frames or not, and I say, for myself, you can let it die. Like Beta.

Yes, like Beta, for all you people who loved it. Just like Beta, so you can all say for years to come, that the wrong one died.

For which I will slap you, hard and fast, with a Beta tape I found.

In truth, it is not a film worth seeing twice, but I was curious and, in my life, that's enough to justify anything.

Set before The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit returns Peter Jackson to the director's role on Middle Earth, to tell the story of how Bilbo Baggins found the Ring of Power, met some dwarves, and generally had a bad time of it. Divided into three films, The Hobbit, unlike the previous Lord of the Rings, is a single, slim novel, but the introduction of extra material to help it work as a prequel for its already existing successful films, as well as a cast of thirteen dwarves, pretty much ensures that it would be, at the very least, two, and yes, three films. If you're a big fan of the book, you will probably have issues with that, but from a structural point of view, the film mirrors the opening of the first Lord of the Rings film fairly closely, ending not with the breaking of the fellowship, but rather with the consolidation of this 'new' fellowship. There are times when it could be cut down--indeed, a much leaner, meaner film could have been made by cutting ten of the thirteen dwarves out, as well as various scenes involving storm giants, goblin kings, and more; but then, in all likely, I wouldn't have seen Christopher Lee again, and that, perhaps, is worth it. Still, it is fairly obvious that Jackson wants to mirror his successful first trilogy in terms of structure, thus creating six films that echo across each other, and should that work it will actually be pretty sweet, assuming of course that you can afford to put aside the time to watch them all.

Overall, I thought the film was decent enough, no better nor worse than the first Lord of the Rings film, but there are some disappointing problems with The Hobbit, mostly stemming with a general inconsistency across it. The dwarves, for example, start off looking vaguely decent, with Richard Armitage's Thorin looking, in all honesty, like a Little Viggo Mortensen, or as I like to call him, L'l Vig. From him, however, it's a swift descent into comically designed dwarves who have the misfortune, as one of my friends pointed out, of looking like they are suffering from down syndrome. Since the film cannot accommodate most of the dwarves to have speaking parts or characterisation, they are instead defined by these poorly thought out designs, and these have the unfortunate result of allowing you to think that the minders are taking the downie kids out for the day. But inconsistency is a general problem with the design of the film, from cardboard pumpkins nestled between real sheep and beautifully built CGI cities, to Gandalf's power, which functions as a bad narrative device, revealing itself as all powerful when it is required and less powerful when not, though this last problem has been in all the films and has more to do with Tolkien than with anything else. But still, it remains a problem, and when at the end of the film Gandalf is blowing flame into pine cones to set the first aflame, you can't help but think, 'Dude, didn't you just knock down a billion goblins? Don't you fight a motherfucking Balrog soon enough? Just go down the fireball the shit outta that pale orc.'

So there's that, and it niggles, all the way through.

But what, I hear you say, of the 48 frames vs 24?

Well, that is the reason I saw the film and I saw it first in 48,and it was... awful, frankly.

It looked like a cheap, fan made version of The Hobbit, where somehow Ian McKellen had been kidnapped and forced the reprise his role under threat of losing his toes. For the first thirty minutes, I actually had to fight the urge to get up and leave, telling myself that it would get better--that I would, somehow, adjust to the faster frame rate, but I never did. I wanted to do so: I had paid the money, I had found myself there, and I was keen for a shiny new film toy. But there was never a moment through the entire thing where I thought, 'This looks great.' I always, always thought it looked awful, and I could never allow myself to flow with it. The CGI looked awful. The actors looked both real and unreal, a weird combination of men and women who never quite fit their part. The scenery was uniformly uninspiring. The list goes on, and it goes on in negative ways, resulting in my first opinion being of the film in 48 frames that it was cheap, nasty, and like bad fan work.

There is a lot of conversation out there about it: one article explains that the the frame rate brings in the Uncanny Valley, where things look too real to sustain disbelief. Another points out that it is simply what we, as viewers, have been conditioned to see, and that in time we will adjust to it. There's more, of course, and you can look them but; but personally, I neither know, nor truly care which one is right--the end product is that my reaction to 48 frames is so negative, so very much in the no category that I would not go to pay and watch a film in the faster frame rate, no matter who was responsible.

Whereas, when I saw the film a second time, in 24 frames per second, it was rather like watching a different film. The inconsistencies of set design and dwarves still remained, but Smaug--what you saw of him--did not look truly awful, the actors looked as if they had settled into their characters, and the CGI was overall fine. Of course, that said, in either 48 or 24 frames per second, the storm giant fight in the mountains was awful: poorly designed, poorly conceptualised, poorly everything. But beyond that, the rest of the film looked great, and it looked like a film, like the previous Lord of the Rings films, with beautiful scenery, a fully designed and crafted world that I did not mind spending the time in, and which I was happy to pay money for.

In the end, it is the reaction of the last emotion that justifies whether to use 48 frames or not, and I say, for myself, you can let it die. Like Beta.

Yes, like Beta, for all you people who loved it. Just like Beta, so you can all say for years to come, that the wrong one died.

For which I will slap you, hard and fast, with a Beta tape I found.

Published on January 01, 2013 16:27

December 26, 2012

The NRA Mindset, As Explained By Die Hard.

On Xmas eve, the girlfriend and I watched Die Hard, because we thought it would be funny to do so.

In case you've never seen Die Hard, it is a film where a young Bruce Willis arrives in LA on Xmas eve to meet with his estranged wife. It being the 80s, she has taken a job in a Japanese corporation that threatens the central character's masculinity and marriage. Fortunately, Alan Rickman and a bunch of European terrorists arrive and by the end, many people will be dead, masculinity will be restored and McClane's wife will have lost the horrible watch that signifies her independence.

Then, a black man will drive them home in a limo.

That the mediocre film has earned a 'classic' status tells us more about the current status of film making than anything else I might write, but that's okay, because I now plan to use it to explain the NRA to you.

Settle in.

Not so long ago, there was a mass shooting in Newtown, in which twenty-six people were killed. Twenty were children, six were adults, teachers at the school. Kept silent for a few weeks, the NRA finally had a press conference in which their spokesperson, Wayne LaPierre, made the now infamous comment, "The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is to have a good guy with a gun." He was arguing for why, at the very least, there shouldn't be some restrictions on the kind of weapons you can buy. He then said you should have armed men and women in schools. Click below to watch, and imagine thousands of Americans heading to gun stores, to stock up.

http://youtu.be/sdWLZ-7hEeE

It is a strange, strange argument to follow, really. For many people outside of the United States, the conversation, filtered through personal rights, freedom of speech, personal safety, the lack of affordable health care, the growing divide of economic status', the culture of fear based on race, age, culture and religion, can be nothing more than a big, dumb echo chamber. One side says one thing, and all you hear is the same words, again and again, with no debate taking place. The difficulty of establishing the debate, of changing a huge part of society, is lost. For many that I know, the argument is as Bill Hicks said once, "There's no connection between owning a gun and shooting a gun and anyone who says otherwise is a Communist," but Hicks, the fine and excellent social comedian, has been dead for eighteen years, and the debate really hasn't moved any.

It won't, either, not until the NRA is changed.

Fortunately for both you and I, there is Die Hard, or as I like to call it The Hope and Dreams of the NRA, in 131 Minutes, which may give you a better understanding of why this is a difficult task.

Die Hard presents us with the fading masculinity of John McClane, as portrayed by a stoic Bruce Willis. In the days when a good man could take a gun on a plane, the New York based Policeman arrives in LA not to spend time with his family, but rather to put an end to his emasculation at the hands of his wife, who has, it might be worth mentioning, begun to his her maiden name instead of his. The connection between McClane's masculinity, his failed marriage, and his gun is established early, as these three things are mentioned within the opening minutes of the film. To understand the mentality of NRA, you have to understand that subtext, which is clearly stating that we are in dire times. Most likely, we have been since the 1970s, when all that free love and feminist bullshit started getting a leg up. A decent, hard working white man will find it tough in this new world. He will be attacked. He will be made to look as a dinosaur, as if he is in a world where he is failing to grow, and at risk of losing not just his voice and power, but his guns, as well.

But never fear, for there are vaguely European men around the corner, and to return to the quote of Wayne LaPierre, "The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is to have a good guy with a gun."

Except what LaPierre really means, as filtered through the film, is "The only way not to feel disempowered is with a weapon," and we shouldn't shirk away from that.

Having taken his weapon on a plane, having worn it in the limo, having kept it through security and up to the 30th floor of a building to meet his wife, John McClane, without shoes, without a shirt, and certainly without any help, is left with only it to stop the men who burst through the front door, heavily armed. McClane's loss of shoes and shirt is a clear message to the audience to demonstrate the importance of the gun, and the power that it has. Having a weapon takes precedence over simple things such as footwear and perhaps a protective jacket, both of which are exploited in later stages of the film, though neither of these cause McClane loss. Indeed, so long as he has a gun, McClane's power is undeniable, and his references to old cowboy films only highlight the 'utopian' Old West that lies at the centre of the NRA and its approach to America. The power of the gun is what motivates McClane to send the dead blond German down with the words, 'Now I Have A Machine Gun, HO HO HO' written on his chest, not in blood, of course, but in a red that is close enough. His actions clearly say to the audience that, now armed with a much better gun than the one he arrived with, he is a much more formidable and dangerous and masculine product--and the response of the bad guys, who clearly outnumber him and have control of the building, but respond in fear, demonstrates the response to this power.

You can imagine how much more power he has when, later, he finds a bag full of plastic explosives. He needs that, by the by, to stop the rocket launcher that is doing bad things to the Police.

There is no moment in Die Hard after McClane runs up the stairwell bare foot and with a gun where he is ever weak. His strength of weapon requires him to be juxtaposed against an overweight black cop whose one moment of characterisation comes when he tells the story of how he accidentally shot a child. Having been emasculated by the act, he put away his gun and rendered himself useless. He is not just a man, but also a Policeman, who can no longer serve and protect. Al--as the character is known--is therefor not afforded any respect until, in the final scenes of the film, he draws his gun again and shoots the final terrorist, who has survived being hanged in an earlier part. This reveal, view in the light I am presenting it to you, is not so surprising when you consider that no weapon was fired in that fight. Masculinity, as clearly displayed through Die Hard, requires a firearm--and in doing so, it allows Al to regain his sense of power, his sense of authority in the world, again.

It is not difficult to use Die Hard to illustrate the mentality of the NRA, and to use it to help better explain how the organisation responds to the situations that are being played out in real life around America. In the heart of the NRA, they believe that the fiction will one day be birthed, and should that moment ever arrive, they will jump up and down and laud whoever it is.

Until then, of course, what men such as Wayne LaPierre hope for, are nothing but a daydream, a fantasy, a fiction, and not until that is recognised, will the NRA begin to change.

In case you've never seen Die Hard, it is a film where a young Bruce Willis arrives in LA on Xmas eve to meet with his estranged wife. It being the 80s, she has taken a job in a Japanese corporation that threatens the central character's masculinity and marriage. Fortunately, Alan Rickman and a bunch of European terrorists arrive and by the end, many people will be dead, masculinity will be restored and McClane's wife will have lost the horrible watch that signifies her independence.

Then, a black man will drive them home in a limo.

That the mediocre film has earned a 'classic' status tells us more about the current status of film making than anything else I might write, but that's okay, because I now plan to use it to explain the NRA to you.

Settle in.

Not so long ago, there was a mass shooting in Newtown, in which twenty-six people were killed. Twenty were children, six were adults, teachers at the school. Kept silent for a few weeks, the NRA finally had a press conference in which their spokesperson, Wayne LaPierre, made the now infamous comment, "The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is to have a good guy with a gun." He was arguing for why, at the very least, there shouldn't be some restrictions on the kind of weapons you can buy. He then said you should have armed men and women in schools. Click below to watch, and imagine thousands of Americans heading to gun stores, to stock up.

http://youtu.be/sdWLZ-7hEeE

It is a strange, strange argument to follow, really. For many people outside of the United States, the conversation, filtered through personal rights, freedom of speech, personal safety, the lack of affordable health care, the growing divide of economic status', the culture of fear based on race, age, culture and religion, can be nothing more than a big, dumb echo chamber. One side says one thing, and all you hear is the same words, again and again, with no debate taking place. The difficulty of establishing the debate, of changing a huge part of society, is lost. For many that I know, the argument is as Bill Hicks said once, "There's no connection between owning a gun and shooting a gun and anyone who says otherwise is a Communist," but Hicks, the fine and excellent social comedian, has been dead for eighteen years, and the debate really hasn't moved any.

It won't, either, not until the NRA is changed.

Fortunately for both you and I, there is Die Hard, or as I like to call it The Hope and Dreams of the NRA, in 131 Minutes, which may give you a better understanding of why this is a difficult task.

Die Hard presents us with the fading masculinity of John McClane, as portrayed by a stoic Bruce Willis. In the days when a good man could take a gun on a plane, the New York based Policeman arrives in LA not to spend time with his family, but rather to put an end to his emasculation at the hands of his wife, who has, it might be worth mentioning, begun to his her maiden name instead of his. The connection between McClane's masculinity, his failed marriage, and his gun is established early, as these three things are mentioned within the opening minutes of the film. To understand the mentality of NRA, you have to understand that subtext, which is clearly stating that we are in dire times. Most likely, we have been since the 1970s, when all that free love and feminist bullshit started getting a leg up. A decent, hard working white man will find it tough in this new world. He will be attacked. He will be made to look as a dinosaur, as if he is in a world where he is failing to grow, and at risk of losing not just his voice and power, but his guns, as well.

But never fear, for there are vaguely European men around the corner, and to return to the quote of Wayne LaPierre, "The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is to have a good guy with a gun."

Except what LaPierre really means, as filtered through the film, is "The only way not to feel disempowered is with a weapon," and we shouldn't shirk away from that.

Having taken his weapon on a plane, having worn it in the limo, having kept it through security and up to the 30th floor of a building to meet his wife, John McClane, without shoes, without a shirt, and certainly without any help, is left with only it to stop the men who burst through the front door, heavily armed. McClane's loss of shoes and shirt is a clear message to the audience to demonstrate the importance of the gun, and the power that it has. Having a weapon takes precedence over simple things such as footwear and perhaps a protective jacket, both of which are exploited in later stages of the film, though neither of these cause McClane loss. Indeed, so long as he has a gun, McClane's power is undeniable, and his references to old cowboy films only highlight the 'utopian' Old West that lies at the centre of the NRA and its approach to America. The power of the gun is what motivates McClane to send the dead blond German down with the words, 'Now I Have A Machine Gun, HO HO HO' written on his chest, not in blood, of course, but in a red that is close enough. His actions clearly say to the audience that, now armed with a much better gun than the one he arrived with, he is a much more formidable and dangerous and masculine product--and the response of the bad guys, who clearly outnumber him and have control of the building, but respond in fear, demonstrates the response to this power.

You can imagine how much more power he has when, later, he finds a bag full of plastic explosives. He needs that, by the by, to stop the rocket launcher that is doing bad things to the Police.

There is no moment in Die Hard after McClane runs up the stairwell bare foot and with a gun where he is ever weak. His strength of weapon requires him to be juxtaposed against an overweight black cop whose one moment of characterisation comes when he tells the story of how he accidentally shot a child. Having been emasculated by the act, he put away his gun and rendered himself useless. He is not just a man, but also a Policeman, who can no longer serve and protect. Al--as the character is known--is therefor not afforded any respect until, in the final scenes of the film, he draws his gun again and shoots the final terrorist, who has survived being hanged in an earlier part. This reveal, view in the light I am presenting it to you, is not so surprising when you consider that no weapon was fired in that fight. Masculinity, as clearly displayed through Die Hard, requires a firearm--and in doing so, it allows Al to regain his sense of power, his sense of authority in the world, again.

It is not difficult to use Die Hard to illustrate the mentality of the NRA, and to use it to help better explain how the organisation responds to the situations that are being played out in real life around America. In the heart of the NRA, they believe that the fiction will one day be birthed, and should that moment ever arrive, they will jump up and down and laud whoever it is.

Until then, of course, what men such as Wayne LaPierre hope for, are nothing but a daydream, a fantasy, a fiction, and not until that is recognised, will the NRA begin to change.

Published on December 26, 2012 22:25

December 19, 2012

The Sun

Published on December 19, 2012 18:53

December 12, 2012

And That's Why Robots Without People Are Cool.

I haven't written a short story since last year. Sirius was, in fact, the last one I wrote.

Now, however, that the book is done, I have time to do a few different things before I head into a new, large project. I have a few ideas, from a comedy, to a book about apocalypses, another about revolutions, but I haven't settled on any, not yet. Time will tell exactly what will happen, but until then, I have spare time to write where the time was used to write a book, and I am going to use that time to write a few short stories, I believe.

There's a couple of stories I've had around for a while, including one I came up with while sitting in a buffet in Minnesota, somewhere. I tried to write the story once, but it didn't take, and I am going to give it a second short, ditching the narration, changing it from first to third person, switching some of the content around and rebuilding it around the original idea, with a few ideas I have had. In other words, I'm keeping the title and trying a new story. I have a couple of Dead American stories in my head, including one about David Carradine, and one about William and Edgar Burroughs who, when I was much, much younger, I thought were brothers. I plan to call that story the Burroughs Brothers, but it requires a bit of reading first and I am toying with the idea of making it a cutup story. Also, it might be long--and long things, I dunno, anything that becomes a novella or larger, becomes so much harder to sell, so we'll see. And I have a Red Sun story planned, and a few other bits and pieces, such as a story about a sin eater, and a ghost story, and I suspect when I have gotten through those, I'll be ready for a new large project. Which of course, probably sounds silly to discuss, since no one asks for anything, the book just done isn't sold, there's an agent and a publisher to find, and etc., but it's no big. It's my time to spend as I please, and if you're not working for what you love, what are you working for?

But it's a strange thing, shifting from a novel structure to a short story one. The form change requires you to alter your mindset. In a simple way, you have to reduce rather than expand, you have to be precise where you might not be. But where plot and subplot become smaller, your choice of language expands. What is hard to sustain for the length of say 120,000 words is much easier on, say, 6000. What is a difficult narrative challenge on that same length, is easier on a shorter one--and you can be more daring, more experimental on a smaller scale for less risk than what you would spend on a larger project that may take a year or two to complete, if you're not confident on the artistic outcome. Or the financial one, if that's how you fly. But there is, at any which way you look at it, a whole mindset change that you have to go through, a whole new voice and suit and set of tricks that you can employ.

Anyhow: I'm off to keep working on that, so peace, laters, and alla that.

Oh, and here's a question I have that I thought of while I watched the trailer for Pacific Rim:

Why, then you have giant robots to fight giant monsters, would you make it so that the people who control the robots are linked in some way that causes the drivers to die while they're sitting in safty? Sure, sure, its an old trope, but why? It's just so unnecessary. Take the people away, have cool robots, you know? I mean, people suck. Especially movie people. They're all finish and no rough. And that line about canceling the apocalypse is awful.

Which is why robots without people make far superior merchan... I mean, films.

Now, however, that the book is done, I have time to do a few different things before I head into a new, large project. I have a few ideas, from a comedy, to a book about apocalypses, another about revolutions, but I haven't settled on any, not yet. Time will tell exactly what will happen, but until then, I have spare time to write where the time was used to write a book, and I am going to use that time to write a few short stories, I believe.

There's a couple of stories I've had around for a while, including one I came up with while sitting in a buffet in Minnesota, somewhere. I tried to write the story once, but it didn't take, and I am going to give it a second short, ditching the narration, changing it from first to third person, switching some of the content around and rebuilding it around the original idea, with a few ideas I have had. In other words, I'm keeping the title and trying a new story. I have a couple of Dead American stories in my head, including one about David Carradine, and one about William and Edgar Burroughs who, when I was much, much younger, I thought were brothers. I plan to call that story the Burroughs Brothers, but it requires a bit of reading first and I am toying with the idea of making it a cutup story. Also, it might be long--and long things, I dunno, anything that becomes a novella or larger, becomes so much harder to sell, so we'll see. And I have a Red Sun story planned, and a few other bits and pieces, such as a story about a sin eater, and a ghost story, and I suspect when I have gotten through those, I'll be ready for a new large project. Which of course, probably sounds silly to discuss, since no one asks for anything, the book just done isn't sold, there's an agent and a publisher to find, and etc., but it's no big. It's my time to spend as I please, and if you're not working for what you love, what are you working for?

But it's a strange thing, shifting from a novel structure to a short story one. The form change requires you to alter your mindset. In a simple way, you have to reduce rather than expand, you have to be precise where you might not be. But where plot and subplot become smaller, your choice of language expands. What is hard to sustain for the length of say 120,000 words is much easier on, say, 6000. What is a difficult narrative challenge on that same length, is easier on a shorter one--and you can be more daring, more experimental on a smaller scale for less risk than what you would spend on a larger project that may take a year or two to complete, if you're not confident on the artistic outcome. Or the financial one, if that's how you fly. But there is, at any which way you look at it, a whole mindset change that you have to go through, a whole new voice and suit and set of tricks that you can employ.

Anyhow: I'm off to keep working on that, so peace, laters, and alla that.

Oh, and here's a question I have that I thought of while I watched the trailer for Pacific Rim:

Why, then you have giant robots to fight giant monsters, would you make it so that the people who control the robots are linked in some way that causes the drivers to die while they're sitting in safty? Sure, sure, its an old trope, but why? It's just so unnecessary. Take the people away, have cool robots, you know? I mean, people suck. Especially movie people. They're all finish and no rough. And that line about canceling the apocalypse is awful.

Which is why robots without people make far superior merchan... I mean, films.

Published on December 12, 2012 20:48

December 4, 2012

The Next Big Thing: Ten Questions Meme

I was tagged by the ever talented Brendan Connell for the Next Big Thing Meme that is going around. No doubt, he is planning his parties to involve copious amounts of cocaine and women and men and riches now, since he (and therefor I) will be billionaires before the week is out.

I plan to be completely corrupt.

Anyhow:

1) What is the title of your next book?

Immolation.

Until, y'know, it changes.

2) Where did the idea come from for the book?

A number of things, as always. Immolation is my big fantasy novel on a moderate diet, which I say because it pulls only 120, 000 words, and not 300, 000. But it's primary influence is pretty much the steady diet of big fantasy that I consumed as a teenager. In part, I wanted to capture that original love again, as closing in on fifteen years writing and selling (sometimes well, sometimes not) had left me a little burnt out--the business of art can be kinda rough, you know, and I had had my ups and downs in that. There was a period when I wasn't sure what I wanted out of it, if it was worth it, and so I returned to all the original things I loved, and I figured I'd write a big fantasy, the kind I'd like to read now, which perhaps explains why its set in a world full of dead gods, with immortals, fanatics, and betrayal.

Most of the content I made up as I went along, but the immortals and their war, that came to me while driving along a road up in Darwin. For no particular reason: I was just daydreaming.

3) What genre does your book fall under?

It's a fantasy novel. If everything goes well, it'll sell as a trilogy, which is the first of those that I've written. If all goes badly, then the next novel I'm going to write is either going to be a comedy, or a book about apocalypses.

Immolation is set fifteen thousand years after the War of the Gods. During that war, the world as the characters know it changed: the sun fractured into three, the ocean turned dark and rose, awful cold struck parts of the world, the entire planet was plunged into darkness for ten days, resulting in years of famine. It was a terrible time, for when a god died, it impacted on the world in an awful way, and after the last of them died, there came their 'children', men and women who said they were they descendants of the gods, the inheritors of their power. After centuries of bloody war, they established a series of terrible kingdoms that, a thousand years back, fell when they renounced their power--or so, most of them did. No longer gods, the men and women with the power of the gods are never quiet, but their power is a fragile thing, lost beneath capitalism, democracy, and they must compete against all of that to remain relevant.

Which doesn't begin to explain the army that is marching up the Spine of Ger, where the giant god himself lies, dead beneath the stone.

Clearly I need to work on this synopsis thing (it is, in fact, what I am working on today, in case you're curious (I know you're not)).

4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

I wouldn't.

You know, questions like this always bother me, because they imply, somehow, that film is more interesting, or somehow more complete than prose. Now, I like film, I do, but I really do think film would be a lot better off if it stopped adapting novels and just worked on original work. In addition to that, if I wanted to write scripts and work with actors, I'd be a scriptwriter--and then I'd worry about which actors I'd want to be part of the work. But I'm not. I'm a down and out author and I work in prose so the last thing I really think of is film and what bad actor is going to play a part in one my pieces that no one has bought or shown interest in.

Also, and perhaps this is just a personal thing, but so many films are shithouse these days, I'd just rather read a book. I'm currently reading Graham Greene's the Power and the Glory, for example. I plan to read more--I know very little of his work.

5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Er.

On the back of a dead god, a girl is on fire, and an army is marching.

6) When will the book be published?

Take your guess.

7) How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

It's hard to say. The messy, vomit draft no one could read? Probably around six months, though the end looked nothing like it does now. The decent, first draft that I could read half of? Maybe twelve. I edit a lot as a write, so nothing is ever clear like that. I finished the first version of it in about fourteen or sixteen months, then spent another six or so months rewriting and editing. Took about two years, all up--and that's with working, having my girlfriend move countries, etc.

8) What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

No idea.

You know, originality isn't a big thing in these questions, is it? Like, what is my book like, who would I want to play in the movie version... you know, I was influenced by a lot of creation stories in various religions, and myths and such that exist around. Could I say my book is like all the books of religions rolled into one?

9) Who or what inspired you to write this book?

I mostly covered this, yeah?

Could I say Jesus and Buddha and L. Ron. Hubbard?

10) What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

What else do you need?

So, there you go. I'm not going to pass it on because if you wanna do it, feel free. If you don't, hey, no stress.

I plan to be completely corrupt.

Anyhow:

1) What is the title of your next book?

Immolation.

Until, y'know, it changes.

2) Where did the idea come from for the book?

A number of things, as always. Immolation is my big fantasy novel on a moderate diet, which I say because it pulls only 120, 000 words, and not 300, 000. But it's primary influence is pretty much the steady diet of big fantasy that I consumed as a teenager. In part, I wanted to capture that original love again, as closing in on fifteen years writing and selling (sometimes well, sometimes not) had left me a little burnt out--the business of art can be kinda rough, you know, and I had had my ups and downs in that. There was a period when I wasn't sure what I wanted out of it, if it was worth it, and so I returned to all the original things I loved, and I figured I'd write a big fantasy, the kind I'd like to read now, which perhaps explains why its set in a world full of dead gods, with immortals, fanatics, and betrayal.

Most of the content I made up as I went along, but the immortals and their war, that came to me while driving along a road up in Darwin. For no particular reason: I was just daydreaming.

3) What genre does your book fall under?

It's a fantasy novel. If everything goes well, it'll sell as a trilogy, which is the first of those that I've written. If all goes badly, then the next novel I'm going to write is either going to be a comedy, or a book about apocalypses.

Immolation is set fifteen thousand years after the War of the Gods. During that war, the world as the characters know it changed: the sun fractured into three, the ocean turned dark and rose, awful cold struck parts of the world, the entire planet was plunged into darkness for ten days, resulting in years of famine. It was a terrible time, for when a god died, it impacted on the world in an awful way, and after the last of them died, there came their 'children', men and women who said they were they descendants of the gods, the inheritors of their power. After centuries of bloody war, they established a series of terrible kingdoms that, a thousand years back, fell when they renounced their power--or so, most of them did. No longer gods, the men and women with the power of the gods are never quiet, but their power is a fragile thing, lost beneath capitalism, democracy, and they must compete against all of that to remain relevant.

Which doesn't begin to explain the army that is marching up the Spine of Ger, where the giant god himself lies, dead beneath the stone.

Clearly I need to work on this synopsis thing (it is, in fact, what I am working on today, in case you're curious (I know you're not)).

4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

I wouldn't.

You know, questions like this always bother me, because they imply, somehow, that film is more interesting, or somehow more complete than prose. Now, I like film, I do, but I really do think film would be a lot better off if it stopped adapting novels and just worked on original work. In addition to that, if I wanted to write scripts and work with actors, I'd be a scriptwriter--and then I'd worry about which actors I'd want to be part of the work. But I'm not. I'm a down and out author and I work in prose so the last thing I really think of is film and what bad actor is going to play a part in one my pieces that no one has bought or shown interest in.

Also, and perhaps this is just a personal thing, but so many films are shithouse these days, I'd just rather read a book. I'm currently reading Graham Greene's the Power and the Glory, for example. I plan to read more--I know very little of his work.

5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Er.

On the back of a dead god, a girl is on fire, and an army is marching.

6) When will the book be published?

Take your guess.

7) How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

It's hard to say. The messy, vomit draft no one could read? Probably around six months, though the end looked nothing like it does now. The decent, first draft that I could read half of? Maybe twelve. I edit a lot as a write, so nothing is ever clear like that. I finished the first version of it in about fourteen or sixteen months, then spent another six or so months rewriting and editing. Took about two years, all up--and that's with working, having my girlfriend move countries, etc.

8) What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

No idea.

You know, originality isn't a big thing in these questions, is it? Like, what is my book like, who would I want to play in the movie version... you know, I was influenced by a lot of creation stories in various religions, and myths and such that exist around. Could I say my book is like all the books of religions rolled into one?

9) Who or what inspired you to write this book?

I mostly covered this, yeah?

Could I say Jesus and Buddha and L. Ron. Hubbard?

10) What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

What else do you need?

So, there you go. I'm not going to pass it on because if you wanna do it, feel free. If you don't, hey, no stress.

Published on December 04, 2012 15:57

December 3, 2012

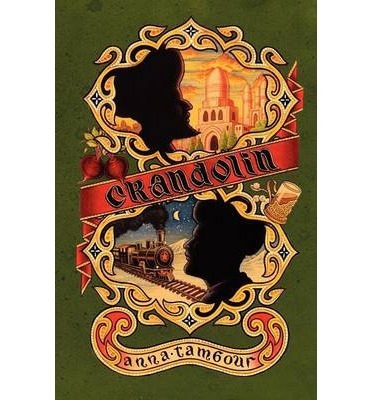

Crandolin

Anna Tambour's new novel,

Crandolin

, has been released by Chomu Press.

Tambour is a fine, but often neglected Australian author who deserves a much larger audience than she has. You could do much worse than checking out her book--in fact, you would be doing much worse by not doing just that.

It is, after all, the only novel ever inspired by postmodern physics and Ottoman confectionery.

Tambour is a fine, but often neglected Australian author who deserves a much larger audience than she has. You could do much worse than checking out her book--in fact, you would be doing much worse by not doing just that.

It is, after all, the only novel ever inspired by postmodern physics and Ottoman confectionery.

Published on December 03, 2012 15:26

December 2, 2012

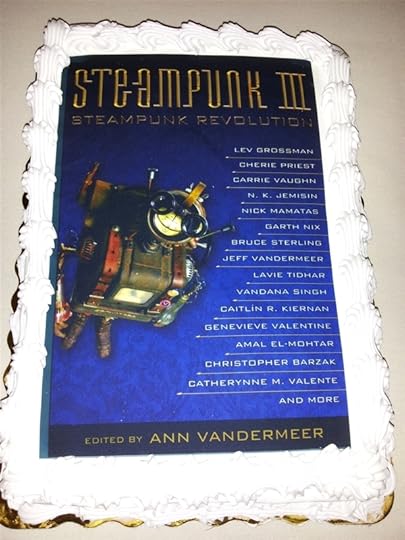

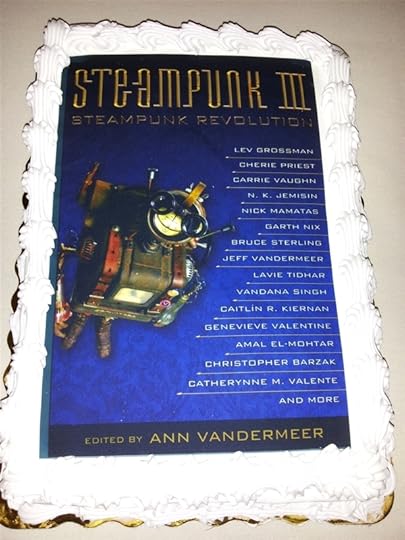

Steampunk Revolution, Official Release

Steampunk III: Steampunk Revolution is officially released today. Here is a cake that has a cover of the book on it:

Edited by the always lovely Ann Vandermeer, the book contains a reprint of my Red Sun story, 'Possession', and includes pieces by Christopher Barzak, Paolo Chikiamco, Amal El-Mohtar, Jeffrey Ford, Lev Grossman, Samantha Henderson, Leow Hui Min Annabeth, N.K. Jemison, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Malissa Kent, Andrew Knighton, Nick Mamatas, David Erik Nelson, Morgan Johnson, and Fritz Swanson, Garth Nix, Cherie Priest, Margaret Ronald, Christopher Rowe, Vandana Singh, Bruce Sterling, Karin Tidbeck, Lavie Tidhar, Catherynne M. Valente, Genevieve Valentine, Jeff VanderMeer, Carrie Vaughn, J.Y. Yang, Jaymee Goh, Margaret Killjoy, Austin Sirkin.

Clearly, as the capitalist holidays run towards us, you want to buy and buy and buy.

Edited by the always lovely Ann Vandermeer, the book contains a reprint of my Red Sun story, 'Possession', and includes pieces by Christopher Barzak, Paolo Chikiamco, Amal El-Mohtar, Jeffrey Ford, Lev Grossman, Samantha Henderson, Leow Hui Min Annabeth, N.K. Jemison, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Malissa Kent, Andrew Knighton, Nick Mamatas, David Erik Nelson, Morgan Johnson, and Fritz Swanson, Garth Nix, Cherie Priest, Margaret Ronald, Christopher Rowe, Vandana Singh, Bruce Sterling, Karin Tidbeck, Lavie Tidhar, Catherynne M. Valente, Genevieve Valentine, Jeff VanderMeer, Carrie Vaughn, J.Y. Yang, Jaymee Goh, Margaret Killjoy, Austin Sirkin.

Clearly, as the capitalist holidays run towards us, you want to buy and buy and buy.

Published on December 02, 2012 18:43

November 27, 2012

The Archway Publishing Scam

This morning, I woke up to discover that Simon and Schuster have begun a self publishing service. Or, as I like to call it, a gouge and leave you bleeding in an alley service:

It's a fairly impressive business they've begun, one that, if you're curious, will ensure that your self published books are sold at the same cost as books from publishers, which would certainly be cynical of me to point out, given other self publishing successes who have undercut traditional publishers. Certainly would be.

Here's the cost breakdown:

Royalties are based on the net payments we actually receive from the sale of printed or electronic (e-book) copies of your book, minus any shipping and handling charges or sales and use taxes. Since retail and wholesale customers purchase at a discount, the royalty amount you receive depends on what types of customer bought your book, the channel through which they purchased, and any discount they received.

Here are two examples of common sales transactions.

The cover price (list price) for your book is $17.95. Your Archway Publishing royalty rate is 50 percent.

But to me, the best part, the part that says, I-Am-Here-to-Take-Full-Advantage-of-You, is the different kind of publishing packages you can purchase. Beginning with the small sum of but two grand (it's actually $1,999, but c'mon) you can get classic author support, a standard cover design and a standard interior layout. Well! Let the jokes begin! Classic support! If it's anything like the classic support I know, then you'll be lucky to hear from anyone, your cover will be a recycled image, and the design and layout will be put into a program. Or, of course, you could throw down $3,799 dollars and get some elite cover and book design, which may or may mean an original image, but still a vague sense of author support. You have to pay at least six grand to move up to 'concierge' author support (okay, it's $5,999) and that'll grab you a DIY audiobook--the DIY says it all, really, doesn't it--and a couple of tickets to the BookExp of America. Fly yourself, of course. Moving up to ten grand ($9,999) will grab you all that and then a premium book trailer to be housed on youtube. Really, four grand for a trailer about your book. If anything, this next step says you should get into film, because that's where the money is. Or, you know, become a publicist, because for fifteen grand ($14,999) you get one of those. It's a social media publicist, of course, and they'll help you get onto twitter, facebook, blogging, and tell you who to target yourself towards, based on your book. Truly, such help is worth a full five grand after that stylish book trailer you just paid for.

Here's the link to it all.

At the end of the day, when reading this, if you wanted to self publish your work, the best bet is to take your fifteen grand and do it yourself, then continue to undercut the traditional publishers. Simon and Schuster's program offers the air of legitimacy, but it really doesn't give you any more than if you did it yourself (which, lets face it, is an ever evolving state of legitimacy anyhow). If you don't want to self publish it, then you're on the trail of agents and publishers, both big and small, and you want someone who will actually be supportive and believe in your work, which is not what this program will provide. As we continue into the century, the divide between self published and published is starting to reduce itself to how much of a gamble you'd like to take on payment (none upfront vs some upfront) and how much you value yourself as a designer, advertiser and publisher of your own work.

Simon & Schuster has created Archway Publishing to help writers self-publish fiction, nonfiction, business and children’s books.

They will run the new service with help from Author Solutions, the self-publishing company acquired by Pearson for $116 million in July.

Archway Publishing will include “editorial, design, distribution and marketing services” for its authors, all these tools coming from Author Solutions. Fiction options range from $1,999 Author package to the $14,999 Publicist package. The business book options start at $2,199 and go as high as $24,999.

It's a fairly impressive business they've begun, one that, if you're curious, will ensure that your self published books are sold at the same cost as books from publishers, which would certainly be cynical of me to point out, given other self publishing successes who have undercut traditional publishers. Certainly would be.

Here's the cost breakdown:

Royalties are based on the net payments we actually receive from the sale of printed or electronic (e-book) copies of your book, minus any shipping and handling charges or sales and use taxes. Since retail and wholesale customers purchase at a discount, the royalty amount you receive depends on what types of customer bought your book, the channel through which they purchased, and any discount they received.

Here are two examples of common sales transactions.

The cover price (list price) for your book is $17.95. Your Archway Publishing royalty rate is 50 percent.

Wholesale Example:

A retailer places an order for your book through Ingram Book Company, a wholesaler. Ingram, in turn, purchases your book from Archway Publishing at a discount. Your royalty on this sale is calculated as follows:

$17.95 (SRP "Suggested Retail Price")

- $9.87 (55% Wholesale Discount)

= $8.08 (Net after Wholesale Discount)

- $4.97 (COGS "Cost of Goods Sold")

= $3.11 (Net after COGS)

x 50% (Royalty Rate)

= $1.56 (Royalty Earned from a retail sale)

Web Sale Example:

Another scenario occurs when a consumer comes to the Archway Publishing bookstore and purchases your book directly. Your royalty on this sale of the same book is calculated as follows:

$17.95 (SRP "Suggested Retail Price")

- $4.97 (COGS "Cost of Goods Sold")

= $12.98 (Net after COGS)

x 50% (Royalty Rate)

= $6.49 (Royalty Earned from a web sale)

Please be aware that the largest retailers, including Barnes & Noble and Amazon, place orders for print copies of Archway Publishing titles through Ingram, so those orders will appear as wholesale sales on your royalty statement.

But to me, the best part, the part that says, I-Am-Here-to-Take-Full-Advantage-of-You, is the different kind of publishing packages you can purchase. Beginning with the small sum of but two grand (it's actually $1,999, but c'mon) you can get classic author support, a standard cover design and a standard interior layout. Well! Let the jokes begin! Classic support! If it's anything like the classic support I know, then you'll be lucky to hear from anyone, your cover will be a recycled image, and the design and layout will be put into a program. Or, of course, you could throw down $3,799 dollars and get some elite cover and book design, which may or may mean an original image, but still a vague sense of author support. You have to pay at least six grand to move up to 'concierge' author support (okay, it's $5,999) and that'll grab you a DIY audiobook--the DIY says it all, really, doesn't it--and a couple of tickets to the BookExp of America. Fly yourself, of course. Moving up to ten grand ($9,999) will grab you all that and then a premium book trailer to be housed on youtube. Really, four grand for a trailer about your book. If anything, this next step says you should get into film, because that's where the money is. Or, you know, become a publicist, because for fifteen grand ($14,999) you get one of those. It's a social media publicist, of course, and they'll help you get onto twitter, facebook, blogging, and tell you who to target yourself towards, based on your book. Truly, such help is worth a full five grand after that stylish book trailer you just paid for.

Here's the link to it all.

At the end of the day, when reading this, if you wanted to self publish your work, the best bet is to take your fifteen grand and do it yourself, then continue to undercut the traditional publishers. Simon and Schuster's program offers the air of legitimacy, but it really doesn't give you any more than if you did it yourself (which, lets face it, is an ever evolving state of legitimacy anyhow). If you don't want to self publish it, then you're on the trail of agents and publishers, both big and small, and you want someone who will actually be supportive and believe in your work, which is not what this program will provide. As we continue into the century, the divide between self published and published is starting to reduce itself to how much of a gamble you'd like to take on payment (none upfront vs some upfront) and how much you value yourself as a designer, advertiser and publisher of your own work.

Published on November 27, 2012 14:47