Anthony Metivier's Blog, page 22

March 9, 2020

10 Ways Your Memory Can Help Keep You Safe During a Pandemic

Source: Flickr

Coronavirus. COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2.

It seems like you can’t read the news without hearing something about the latest global outbreak.

And with misinformation spreading faster than the virus itself, how are you supposed to know what’s truth and what’s not?

More importantly, how can you maintain your health (and sanity) during a time when everyone seems to be on the verge of panic?

Let’s take a deep breath…

And then look at 10 ways you can stay mentally and physically healthy during this worldwide crisis — by using your memory (and some helpful tips from the folks on the front lines).

Ready to do this?

Let’s go.

Want to skip ahead?

1. Scrub-a-dub-dub

2. Pretend your hands are on fire

3. Don’t listen to Uncle Joe

4. Do listen to the experts

5. Stock up, modestly

6. Memorize phone and other important numbers

7. Meditate and get your Zzzs

8. Save face masks for health care providers

9. Memorize directions

10. Don’t panic

Live Your Magnetic Life

As we begin, remember what the wise writers of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy would advise us…

Don’t panic.

One of the best ways to survive any crisis is to stay calm, be rational, and remember that nothing in life is certain.

Well, other than our first tip for staying healthy…

1. Scrub-a-dub-dub

You may be getting a little tired of hearing it, but properly washing your hands is one of the best things you can do to stay healthy.

Whether you sing “Happy Birthday” (twice) or some other song, be sure to wet your hands thoroughly, lather everywhere, clean under your fingernails, rinse, and dry.

Even better, Dr. Edith Bracho-Sanchez, a pediatrician with Columbia University Medical Center, advises a new habit for everyone: wash your hands as soon as you walk through the door of your home.

And even if your hands are clean, remember: don’t touch your face.

2. Pretend your hands are on fire

But, but, but!

“How can I keep from touching my face? That’s so hard to do!”

For the technique I’ve been using, I imagine I have gloves of fire on my hands and don’t want to touch my face.

If you don’t like the image of fire, try ice or some other substance. The point is to use a simple visualization that you link with your body.

To remind yourself, you can draw a small dot or even the word “fire” or “ice” on the back of your hand.

Lucid dreamers often do this to help them remember to do “reality testing.”

These approaches are linked to another kind of technique for remembering where you put your keys, such as imagining them explode when you set them down. You are simply adding an imaginary layer of multi-sensory imagery to a regular operation.

Here’s another related tip:

If you want to combat that effect when you leave your living room to get a pair of scissors in the kitchen, only to forget what you are looking for, you can imagine scissors in your hand and make a fist around the imaginary pair.

3. Don’t listen to Uncle Joe

No offense to Joe, but unless he works for one of the global health organizations whose work revolves around mitigating the effects of COVID-19… he’s probably not the best source of information.

The same goes for most of the internet. Seriously.

Most of the mainstream media outlets are driven by views and clicks. And what gets them the most eyeballs?

DRAMA! TERRIBLE THINGS!! THE WORLD IS ENDING!!!

Instead of allowing the media to drive your personal narrative and understanding of what’s (really) happening, choose your news sources wisely.

If you’re wondering who to trust, here’s a chart that breaks down media bias.

4. Do listen to the experts

For health-related issues, it’s also good to look to the experts. In this case, the World Health Organization (WHO).

Additionally, for readers in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For those of us in Australia, the national Department of Health. And for readers elsewhere in the world, your trusted regional or national healthcare organizations.

I’ve also been watching Dr. John Campbell’s detailed daily updates on YouTube, including this great one about washing your hands as soon as you get home:

Tim Ferriss recently shared the following recommendations on how to stay informed:

A Center for Health and Security newsletter

And a curated Twitter list

The trick is to make sure your reading comprehension skills are strong. A lot of the panic comes from people failing to understand what they’re reading and the nature of scientific processes.

You can also talk with your own medical professional:

When I was booking my flights to go to TEDx Docklands in Melbourne (February 2020), I visited my family doctor to air my concerns.

As I told our doctor, even though speaking at the event presented a huge opportunity for me as a memory expert, I didn’t want to infect others should I become sick.

She said two things:

We all have to simply go about our lives, and

If you’re going to get sick, get sick early. Later, it could be very difficult to get help.

The second point involves a bit of dark humor, but if you really think it through, it does make sense. Although my heart didn’t feel 100% right about it, I went, and to my knowledge, none of the attendees has fallen ill.

And thanks to the memory techniques, I could relax and deliver because I know how to memorize a speech.

I did keep close to our hotel, however. We can visit the art galleries and museums next time we’re in Melbourne.

5. Stock up, modestly

I bought extra water, food, and toilet paper weeks ago.

This was especially important because I have multiple food sensitivities. I won’t be able to just whip into any old can of chili if I can’t make it to the grocery store.

As you prepare, think about other things you would need if you had to self-quarantine or practice social distancing for a week or two.

For example, do you have a fire blanket for every person in your home?

At first, my wife thought I was insane for buying them, but it only takes a second to put one over your shoulders in the event of an emergency — something you won’t be able to do if you aren’t prepared.

Health experts also recommend that anyone who uses prescription medication on a regular basis have at least a 30-day supply on hand.

6. Memorize phone and other important numbers

Sure, you’ve got everyone’s number stored on your phone.

So… what are you going to do if you lose your phone when you’re too sick to keep track of things?

Or how about your insurance number?

There are endless situations where you might need your bank account number, phone numbers of your immediate family, and credit card instantly on the tip of your tongue.

Remember, building mental strength is helpful in emergencies as well as your day to day life.

7. Meditate and get your Zzzs

It’s not just helpful for your memory — getting enough sleep, eating well, and practicing mindfulness meditation can also improve your immunity.

One simple body scan visualization that won’t necessarily protect you from a virus – but can be very relaxing and orient your mind on health – goes like this:

As you lay on your back, imagine a healthy color like blue or green entering your lungs and flowing through your body. Try to follow it through your lungs and veins all the way down to your toes.

Then, as you breathe out, imagine all the impurities this healthy color has picked up exiting your breath in a color like white. Imagine it disappearing into the atmosphere.

Repeat 5-10 times, until your body begins to feel relaxed. You can even come up with your own variations.

8. Save face masks for health care providers

Neither the WHO or the CDC recommend face masks for community use in healthy individuals. If you are healthy, the only time they do recommend wearing protective gear is when taking care of a person with a suspected or confirmed 2019-nCoV infection.

If you’re just trying to stay healthy, the jury is out on whether wearing a mask helps or hurts your chances. In fact, NPR has done quite a bit of in-depth reporting about the matter.

If you’re very prone to touching your face – and the visualization above doesn’t help – wearing a mask might help you stop touching your face. But for many people, it just creates another surface for infectious particles to get trapped on.

And remember: if you do touch your face, be sure to wash up.

9. Memorize directions

It’s one thing to consume directions — like “don’t buy masks,” or “call your doctor before visiting their office if you’re experiencing symptoms.”

But to really internalize the directions, you can memorize them. As mentalist Derren Brown points out in his book Tricks of the Mind, by memorizing to-do lists, he was more likely to actually complete them and follow the plan.

Here’s how to do it:

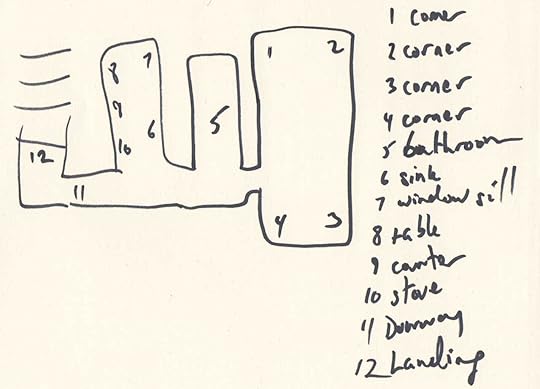

Create a Memory Palace that has enough space for the directions you want to memorize.

If you’ve never created a Memory Palace before, here’s a free training to teach you how:

Let’s say you’re memorizing the direction to call the clinic before showing up.

On Magnetic Station one of the Memory Palace, imagine yourself picking up a big red phone and calling the clinic.

To memorize the direction not to panic, imagine a giant cartoon version of yourself suddenly relaxing after panicking. Or, think of a pop culture character you know who tends to freak out, like Homer Simpson, and imagine him rapidly transforming himself into one of his more vegetative states.

Think these kinds of visualizations are unlikely to work?

Think again: Dr. Tim Dalgliesh is just one psychologist who has shown that pairing positive emotional states with a Memory Palace helps you not only act more positively, but also remember to do so.

10. Don’t panic

I’ll say it again. And again.

During a global health outbreak moving as quickly and evolving as rapidly as this one, the best thing healthy people can do is to stay calm, informed, and prepared.

If you’re having trouble keeping calm, the WHO compiled some good recommendations for coping with the stress of this outbreak:

Live Your Magnetic Life

I’ll leave you with a few parting thoughts:

Be good to people now. Love your loved ones while you can. And don’t wait for things like coronavirus to be a wakeup call because as Michael Gusman reminds us, things can happen anytime.

Until the next time, take care and keep yourself Magnetic (and wash those hands)…

The post 10 Ways Your Memory Can Help Keep You Safe During a Pandemic appeared first on Magnetic Memory Method - How to Memorize With A Memory Palace.

February 25, 2020

Anastasia Woolmer on Memorizing Movement and Mastering Recall

No one has demonstrated the multi-sensory nature of memory techniques with as much grace as Anastasia Woolmer.

No one has demonstrated the multi-sensory nature of memory techniques with as much grace as Anastasia Woolmer.

In fact, Anastasia has literally married memory training with physical activity.

This means that she’s released the Memory Palace journey and associated memory techniques from the mind.

One of those ways is through dance.

This is wonderful, because I’m asked frequently about how to memorize movement.

Although I’ve played around with it, finally our community has access to the processes by someone who has spent a great deal of time with this memory-movement skill.

It turns out there’s a lot to it – and some standards that already exist in dance.

To supplement the audio, you can check out a demonstration for yourself by watching Anastasia’s TEDx presentation. Then, dig into this episode of the Magnetic Memory Method and learn the “mnemonic logic” behind the movement.

As you can already tell, Anastasia reminds us that mental imagery is not just visual.

Indeed, the best memory strategies always encompass all our senses. The most solid and beneficial techniques incorporate all these senses into a unique and powerful tool that is universally accessible.

The Path Of A WorldClass Memory Expert and Memory Athlete

On top of being a self-taught, two-time Australian Memory Champion, Anastasia is a public speaker, memory coach, former professional dancer and contestant on Australian Survivor: Champions v Contenders.

As the Australian Memory Champion, she was the first female to hold the title in the country. Anastasia set the record for the most binary digits remembered in five minutes at 360, the most numbers remembered in 15 minutes, 304, and the most consecutive spoken digits without an error, at a remarkable 86.

Anastasia and I discuss her path, and transformation, from a widely-held (and untrue) belief that her memory was fixed and could not be improved, into a history-making Australian memory champion. As we proceed, you’ll learn more about how she married ancient memory techniques to modern dance to create a method that truly worked for her.

And this podcast and her wisdom is not just for aspiring dancers or choreographers.

As Anastasia demonstrates during our chat, you don’t have to settle for rigid and inflexible learning techniques. You don’t have to be frustrated with attaining your learning goals. You are not tied down to any “right way” to do things.

In the world of dance, I believe this is called free-styling. You’re not bound by the choreography of what moves you should make. Listen to your body, all your senses, and make the journey, and the dance, your own!

Press play now and discover:

The two components necessary to be a “fit” human

How economics relates to memory improvement

The best way to deal with the “initial panic” of an influx of new information to be committed to memory

The benefit of memory exercise in a variety of environments, and why noisy surroundings can actually be great for memory training

The “trick” to multitasked focus, and a simple activity that anyone can do to strengthen that skill

The best method for recovering from memory mishaps, even in a public speaking setting

How to use the Method of Loci to memorize and deliver a speech

The similarities between writing a story and creating a Memory Palace journey

When you shouldn’t memorize anything verbatim (even if it seems like a good idea and you want to strive for perfection – hint: you shouldn’t!)

How learning more, more information, more skills, and taking on more hobbies, is an endless cycle, and why you want to be on it!

The secret dancers naturally utilize that you will want to always employ in learning new information

Why the best methods to memory improvement are multifaceted, multi-sensory, and completely inclusive and customizable, and why individuality is the most important facet of incorporating memory training into your life

Further Resources on the Web, this podcast, and the MMM Blog:

Anastasia Woolmer’s official website

Anastasia’s Master Recall courses

5 Sensory Memory Exercises for Better Memory Palace Success (MMM Blog)

Aphantasia: Develop Your Memory Even if you Cannot See Mental Images (MMM Blog)

Tansel Ali On How Gratitude Can Help You Remember Almost Anything

The post Anastasia Woolmer on Memorizing Movement and Mastering Recall appeared first on Magnetic Memory Method - How to Memorize With A Memory Palace.

February 18, 2020

Explicit Memory: Everything You Need To ERASE The Confusion

Do you remember your first trip?

Do you remember your first trip?

Maybe it was to Paris, or just a school outing.

My first travel memory is with my family. We crossed much of Canada, camping and fishing our way from British Columbia to New Brunswick.

And my first school trips were to a farm and a chocolate factory. You better believe I will never forget the chocolate trip!

No matter where you went for your first outing, I bet you can describe it in all its technicolor details.

Or how about this:

Do you know the capital of Iceland? Or what about some other fact you memorized for a pop quiz or trivia night a few months ago?

In all these instances, it is your explicit memory that helps you intentionally recollect facts and personal experiences.

Amazing, isn’t it?

In this post, I’ll explain all about explicit memory, how you form them and how you can build better and stronger memories.

This is what we’ll cover:

What is Explicit Memory?

Are There Different Types of Explicit Memory?

Implicit and Explicit Memory — How Do They Differ?

How Do You Form an Explicit Memory?

How Does Your Brain Retrieve an Explicit Memory?

3 Fun Ways to Boost Your Explicit Memory

What is Explicit Memory?

Explicit memory or declarative memory is part of your long-term memory. You use it throughout the day. When you recall the time of your dentist appointment or recollect your 16th birthday party, you are using your explicit memory.

Explicit memory needs conscious awareness. The cognitive processes of forming explicit memory are also often associative — you link different specific memories to form one consolidated human memory.

There are two types of long-term memory: implicit and explicit memory.

While implicit memory or procedural memory are skills that you pick up unconsciously and unintentionally, explicit memory is everything you actively work on remembering.

Some examples of explicit memory include trying to remember the name of people you meet or trying to cram into your human memory that the capital of Iceland is Reykjavík.

Although implicit and explicit are subtypes of long-term memory, when you think of memory function in “general,” you are referring to the explicit segment.

What’s more? Implicit and explicit types of memory get affected differently with Alzheimer’s disease. While explicit memory is damaged in Alzheimer’s disease, implicit memory remains intact.

Both implicit and explicit memory systems work together in healthy individuals.

Fun fact: there are two other memory processes – short-term memory (also called working memory) and sensory memory (it retains sensory information like those from sounds in the form of echoic memory). A memory must move through these before a lasting long-term memory can be formed.

Are There Different Types of Explicit Memory?

We can categorize explicit memory into episodic memory and semantic memory.

In 1972, Canadian experimental psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist Endel Tulving found a few differences between episodic and semantic memories and proposed the distinction between these two types of explicit memory.

Curious?

Let’s take a quick look:

What is Episodic Memory?

Episodic memory, like the name implies, is a memory of a previous experience, past event, or activity.

Memories of specific events like your first kiss, that fantastic trip to Greenland, or your first prom are all episodic memories. Some episodic memories are also autobiographical, like remembering your date of birth or the street name where you grew up.

You can consciously recollect these past personal experiences.

You’re usually able to associate how you felt during these specific memories. That’s because your emotions are essential when it comes to memory consolidation.

Your brain’s hippocampus is in charge of processing and storing your episodic memories while your cerebellum is involved in retrieval.

If you can recall the excitement of your first day at university or the stress of moving to another home, you can very clearly remember everything that happened on that day based on how that episode made you feel.

That’s the main difference between this type of memory and semantic memory.

What is Semantic Memory?

Semantic memory is usually based on knowledge that you picked up throughout your life and your capacity to recollect this knowledge at will. These aren’t based on personal episodes in your life.

Semantic memory usually refers to general knowledge. Things like how WWI started in 1914 or how the White House looks are examples of semantic memory.

However, it’s not just limited to general knowledge. For example, you know that the sky is blue, what an elephant is, and how to ride a bike.

You probably started learning all of these when you were a kid, as you were starting to experiment and interact with the world around you. You don’t remember how you learned them and yet they’re still consolidated in your mind.

These specific forms of memories aren’t tied to a feeling or to any personal experience.

Implicit and Explicit Memory — How Do They Differ?

As you’ve probably noticed, explicit memory involves conscious recollection.

Whether you remember it based on how you felt that time or based on how hard you studied for that exam, you consciously worked to remember it.

This is not the case with implicit memory.

Implicit memories (often called non-declarative) are those you never consciously tried to remember.

They are a form of memory that you use to interact with the world around you every day. These include your vocabulary, your spatial memory, and your motor skills.

You learned them and then don’t have to relearn again and again to perform them. You usually can’t even remember learning that skill and yet you can do it almost automatically.

An example of implicit memory can be a simple task like how to use a fork, how to boil an egg or even the chorus of ‘Single Ladies’. All of these are unconscious memories that you may not even know you had!

Just reading ‘Single Ladies’ may probably be enough to get that song stuck in your head for the rest of the day. Sorry about that!

How Do You Form an Explicit Memory?

The processes used to form explicit memories are encoding and retrieval.

First, you record or encode information by absorbing it when you read, hear something, or interact with someone. During recording, memories are stored in the hippocampus, which is located in the brain’s temporal lobe.

The hippocampus is the one involved in creating neural connections in different regions. When you’re rehearsing a memory, the memory passes through your hippocampus multiple times.

You have both short-term memory and long-term memory. Anything you remember is first kept in your short-term memory. From there, your hippocampus has the task of deciding if that temporal memory is going to become a long-term memory or simply be forgotten.

If a memory is important, it’s moved to your long-term memory throughout your cerebral cortex. Its exact location will depend on the type of memory.

Physical damage to the cortex (as seen in a magnetic resonance) has been shown to affect your cognitive processes related to memory directly.

Your brain labels most of the memories you make as unimportant and it discards them, so they never make it to long-term memory.

Since explicit memories are part of your long-term memory, these would be facts, figures, experiences, and episodes that your brain consciously moved from short-term to long-term parts of your memory.

For example:

Do you remember the trousers you wore to work two weeks ago?

No, right? That’s because your hippocampus didn’t consider that information relevant enough to retain for longer than a few seconds.

That’s when repetition comes in. The more you retrieve a memory, the easier it’ll be to retrieve it again because you’re telling your hippocampus that it’s important.

Now:

If a young lady happened to notice your trousers and complimented you about them, you would want to tell all your friends about it (as many times as possible, presumably).

At every instance possible, you would repeat the story of how you were just sauntering down the road when this amazingly beautiful girl smiled at you and complimented your trousers.

The more you repeat that story, the more you reinforce that memory and the recording becomes permanent.

You will never forget those trousers. Maybe they even become your lucky trousers!

Once a memory becomes a story, you don’t just remember facts; you remember how those facts made you feel. Your amygdala connects your memories to specific emotions. And you can recall such memories at will.

Is Sleep Important to Form Better Explicit Memories?

There’s a reason why when you’re jet-lagged, or you simply haven’t slept well, you keep forgetting things.

That’s because sleep plays a crucial role in memory formation.

When you sleep, you perform the most crucial part of making new memories: consolidation.

When you’re awake, you acquire the memory or learn a new fact or skill. But it’s only during night time when you sleep that your brain files the memory in a place you can retrieve it later.

And sleeping doesn’t just help you consolidate the memories you’ve gained that day.

When your brain is organizing new memories, it can associate them with older memories as well. This not only helps you remember things better, but also helps you in your creative process by finding links to your memories you didn’t have before.

When you don’t sleep well, your brain simply lacks the time for filing, organizing, and processing new memories, leading to bad recall later. Believe me – I’ve been there!

If you want to remember what you learned here, you better get your 8 hours of beauty sleep tonight.

How Does Your Brain Retrieve an Explicit Memory?

Memories are usually retrieved by association.

When a teacher asks you a question about Independence Day, you’ll probably try to remember the lecture he gave a week before.

Memory isn’t perfect, though.

If you think back to that lecture, you’ll probably remember what the teacher said but not the shoes he was wearing.

That’s because once the explicit memory is consolidated, it is stored by a group of neurons that react in the same pattern created by the original experience. You won’t remember the shoes because they didn’t create an impact on your original experience, so the memory was lost after being a short-term memory.

These patterns are recorded several times over to create redundancy. That way, if there’s damage to the original, you’ll still be able to retrieve the memory.

Can Memories Get Corrupted?

However, this also means memories can become corrupted with time.

Since you can’t notice everything at once – and your mind doesn’t like to have holes – it fills up the gaps between your memories from other similar memories.

If you try to retrieve details from a memory that wasn’t there, your mind may fill that detail with information from a different memory. Then every time you retrieve that memory, you’ll reinforce that false detail into the experience.

That’s why you may be sure you remembered the right thing for a test only to find out you were wrong when getting the result.

Explicit memories don’t have to be retrieved on purpose. Sometimes simple stimuli can act as a trigger. Have you ever smelled some spice or perfume and felt as if you were teleported to another place?

Explicit memories are remembered by an association that your brain makes, in a conscious or unconscious manner.

However you make them, it’s essential to keep up on the state of your memories. One study compared over one thousand Alzheimer’s patients and found that patients who are aware of memory loss are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Why Do You Lose Memory?

Do you keep forgetting things? Don’t get an MRI just yet!

Forgetting things you used to remember is a normal part of the learning and memory process, especially as you age, and it rarely signals memory impairment.

Memories are a use-it-or-lose-it kind of thing. If you don’t remember a particular memory for long enough, your brain’s response is typically to forget it to make space for new ones.

And that’s great! In a healthy brain, time heals all wounds.

However, some people don’t get that luxury.

The findings of different studies that compared the memory process of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder show that PTSD directly impaired the creation of explicit memories in their subjects by affecting brain activity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

This also affected facial emotion recognition since you rely on these areas to remember and recognize those signals.

However, the tormenting effect that other memories typical of PTSD causes are hard to forget.

For experimental psychology, getting better at forgetting is just as big of a challenge as getting better at remembering.

3 Fun Ways to Boost Your Explicit Memory

Since explicit memories are memories you put effort into recording, you can create those at will.

The problem arises when you’re trying to record information that doesn’t seem particularly relevant to your brain.

Imagine you’re at a party and get introduced to five people. By the time you get to the third person, you probably already forgot the name of the first one.

Why? Because your brain wasn’t thinking about it. You were probably more worried about creating a good impression, giving a good handshake, or trying to look friendly.

All that was very important to your brain, so listening to their names was pushed to the side.

How can we solve it?

Here are three fun ways to strengthen your memory performance:

1. Repeat, Repeat, Repeat

Repeating information is an excellent way for temporal memories to become permanent ones. If you make an effort to repeat someone’s name when you get introduced to them, you’re more likely to remember that name for a long time.

Although repetition is usually associated with implicit memories (like riding a bike), it can also help you form explicit memories.

Repeating answers for a test, passwords, and even phone numbers is a simple but proven way to consolidate a memory.

It’s even better when you use elaborative encoding (exercises) because that reduces the amount of repetition while increasing the impact of each.

2. Use Bizarre Association

A great way to remember information is to associate it with things you already know. Try to think about how things make you feel or tie the memory to another strong memory you have. The stronger the connection, the easier it’ll be to remember.

Even the most forgetful person will probably remember another person who shares their moniker.

You can use this technique when you go grocery shopping. What most people do is try to memorize a list of words of what they’re going to buy. Then you associate your grocery list with a number.

A more effective way is to associate it with a more memorable thing, like a recipe.

Why?

Because your brain finds the task of processing and recording visual memories far easier than a list. This is exactly what a study that compared participants involved in a supermarket scenario found: people are more likely to remember the image of their groceries than the simple words.

And, if you’re using a recipe, it doesn’t even have to be a real one!

For example, say you need to buy eggs, milk, tomatoes, toilet paper, and batteries. You can associate all of them by imagining making scrambled eggs with a bit of milk and tomatoes, mixed with batteries and garnished with little bits of toilet paper.

Make it as realistic in your head as you possibly can. Imagine the colors, the smell, the texture, and even the taste.

The more ridiculous your association is, the more memorable it’ll be!

And when you use the Magnetic Memory Method to become a mnemonics dictionary, all the better.

3. Build Memory Palaces

The last two techniques work better combined.

The Memory Palace technique is an ancient way of remembering things. Traced back to the Greeks, it has been used by geniuses like Hannibal Lecter and Sherlock Holmes to remember everything.

Memory Palaces, however, aren’t fiction.

A Memory Palace consists of associating memories to a location you’re familiar with. You visualize that place in your head and you associate memories to parts of that place.

If, for instance, you were to associate the room you’re in with memories, you’d store the information in the corner, the drawers, the ceiling, etc.

That way, whenever you need to remember something, all you need is to go to your mind palace and look it up.

Neat, right?

Make Better Memories

When you build Memory Palaces using the Magnetic Memory Method, you unlock the powers of:

Autobiographical memory

Episodic memory

Semantic memory

Procedural memory

Sensory memory

Iconic memory

…and so much more.

These improvements allows you to move information into explicit memory faster — and with predictable and reliable permanence.

Otherwise, you’re just waiting around for flashbulb memory, and that’s not a strategy.

You know you deserve better.

The long term effects of using the Magnetic Memory Method to remember and recall information is stronger and results in a healthier brain.

So are you ready to give a booster shot to your explicit memory?

Pick up your copy of my free Memory Improvement Kit, and make your memory Magnetic!

The post Explicit Memory: Everything You Need To ERASE The Confusion appeared first on Magnetic Memory Method - How to Memorize With A Memory Palace.

February 11, 2020

Reading Comprehension Strategies: 13 Ways To Eliminate “Rewinding”

We’ve all been there. Drudging through a book that’s hard to grasp.

We’ve all been there. Drudging through a book that’s hard to grasp.

What started out with such enthusiasm soon becomes a joyless task.

‘’What does that mean?’’ you cry out.

And just as soon as you start getting into a reading flow… you’re rewinding again. It’s a killjoy. It sucks the pleasure out of reading.

It’s enough to make you quit.

And the scary thing is you miss out on so much when your reading becomes stagnated.

But reading comprehension strategies are not just for teachers or struggling students. Mature learners need to keep pace with the younger generations and test their comprehension, too.

With better comprehension, you can remember and use more of what you read.

Here’s what we’ll cover today:

1. Something’s Missing From Your Learning Toolbox

2. Be Purposeful For Pleasure’s Sake

3. Physical Books — One Antidote to Digital Amnesia

4. Evaluate and Expand Competence

5. Monitor Understanding To Leap Ahead and Recalibrate

6. Recognizing Story Structure and Maps

7. Generate Questions to Branch Out

8. Make Inferences (and Predictions) Along The Way

9. Seeing With Graphic Organizers

10. Summarizing And Panning for Gold

11. Memory Palace a Stairway To Heaven

12. The Major Method — Where Numbers and Letters Collide

13. Input-Output Lifestyle Choices

The Four Levels of Reading

Your Next Chapter!

Let’s jump in, or if you prefer watching:

1. Something’s Missing From Your Learning Toolbox

How do you improve reading comprehension?

Maybe you’re a teacher and want to help your students with reading comprehension. Or you’re simply trying to uncover reading comprehension strategies for adults. Whatever the case, you realize it’s not just the topic you need to master first, but the correct tools for learning.

In her well-known essay, Dorothy Sayers discusses the lost tools of learning:

‘’Although we often succeed in teaching our pupils ‘subjects,’ we fail lamentably on the whole in teaching them how to think: they learn everything, except the art of learning.”

Since reading uses the information you already know, better memorization leads to clearer reading comprehension. The result? You can understand and remember more of what you read. The cumulative effect is powerful.

2. Be Purposeful For Pleasure’s Sake

Being purposeful about your reading goals aids comprehension. Drill down into your intentions and ask, ‘’what’s in it for me?’’

Why are you reading anyway? If reading isn’t meaningful it can become an empty pursuit. It’s another reason people quit in the second round.

On the other hand, when your reading is aligned with a clear aim, enjoyment follows. Not only that, it aids your memory as time marches on because:

Pleasure is instantly easier to remember!

If you’re still uncertain, start simply. Start practicing regular reading with less challenging novels — this blends enjoyment and momentum. Then when you decide to tackle tougher books your comprehension skills are already well-honed.

3. Physical Books — One Antidote to Digital Amnesia

While digital books have many excellent benefits (cost, search ease, mobility, sustainability, sharing) it’s worth remembering the trusty paper book.

But why would you choose physical books over digital or eBooks?

First, your precious memory plays a vital role in reading comprehension. Digital amnesia affects our cognitive ability to remember – and learn more – faster. Since your aim is to become a better reader through magnetic memory, paper books help to:

Index the material better in your mind

Reference and re-reference while reading

Keep the books visible

Use reading to practice Digital Fasting

Remember page numbers and details

Assimilate reading into your life, and…

Demonstrate the values and virtues of reading from real books and remembering as much as possible from them

In a world of devices, wi-fi, hotspots, and tabs… your physical book can become a spiritual retreat.

4. Evaluate and Expand Competence

Let’s face it: some textbooks are long and (frankly) scary. Every reader can struggle with how these books are presented — with lengthy paragraphs and sentences, and challenging vocabulary.

A good place to start is to evaluate your strengths and weaknesses. The trick is to gauge your level of competence and gradually expand it (E.E.C. = Expand Existing Competence).

What does your typical reading session look like?

Do you start daydreaming after 30mins as your energy drains?

If so, try to push 10 minutes beyond. You might use a Pomodoro timer to take a break after 30 minutes.

It helps to understand your levels of processing effect in the Big Five of Learning:

In other words, your ability to read, write, speak, and listen comes from memory. When you read, write, speak, and listen you put comprehension into memory in the first place.

Memory to Read –> Reading to Memory

It’s a perfect circle that highlights the importance of developing a better memory.

5. Monitor Understanding To Leap Ahead and Recalibrate

Monitoring is about realizing what you know, what’s unclear, and any gaps in your understanding. The method helps you find the blockers to comprehension. By defining issues with comprehension you can tackle them head-on.

Einstein said:

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

When you write, listen, and speak about a text you reflect on its meaning.

It’s a chance to move from vagueness to better clarity. The offshoot is, you can zone in on and identify blockers and get misconceptions out of the way.

Aslo, ask for help.

By sharing your thoughts with a study partner you can get valuable feedback too. This feedback loop can enhance your understanding and uncover any confusing passages. Monitoring comprehension can help you to read more books and supercharge your subject knowledge. This is all part of developing mental strength.

6. Recognizing Story Structure and Maps

Mature learners can benefit from recognizing a story’s structure.

It highlights the branches an author uses to structure the text. The contents, headings, and bibliography sections are obvious places to start. By further delving into the order of the subheadings, the setting, events, and characters begin to unfold.

It’s no surprise that you can also start to guess the theme and predict what might happen. Using your imagination in this way is bound to improve your reading comprehension.

7. Generate Questions to Branch Out

It’s only right that grown-ups should take a more proactive stance to learning. And there really are no silly questions when it comes to your reading goals. Let’s face it, who’s listening? Because this is more like self-reflection behind closed doors.

The mental process of elaboration involves repeatedly asking the classical questions: “who, what, where, when, why, and how?” By questioning and eliciting answers, guesses or theories, you can boost your understanding of a text.

Rather than just reading and being a reactive passenger, you’re driving to understand the context. You engage more with what’s going on through questions. And instead of a mundane reading challenge, you turn the pages with a new curiosity.

Depending on your reading genre you can create unique questions to aid memory and faster learning.

8. Make Inferences (and Predictions) Along The Way

Research by Robert Marzano (2010) states that inference is a foundational 21st-century skill for higher-order thinking.

So how do you make inferences in a book you’re reading? Four words — ‘’read between the lines’. Inference involves drawing conclusions from what’s implied rather than stated directly. Put simply, you use what’s known to make a creative guess about what you don’t know.

It’s about searching for clues in the text to figure out what’s being said from the context.

Then through your exemplary best judgment, you can land on what’s being suggested. Whether your inferences turn out to be wrong or right, you start to glean value and construct meaning.

That just means you have to adjust your thinking as you read.

For example:

What’s not being said?

Based on these clues I think….?

Because of the way these characters act it means….

I think….will find an escape route because….

I predict….will get married

I wonder if….Mr….is the actual villain

I suppose….might become the leader

I predict…. will fail

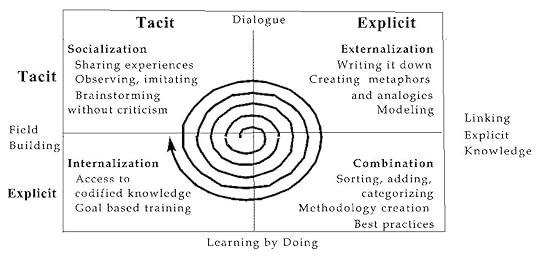

It’s useful to look over Nonaka and Takeuchi (1997) to get an idea of the differences between tacit and explicit knowledge.

Spiral of knowledge (Source: Adapted from Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1997)

9. Seeing With Graphic Organizers

“A picture is worth a thousand words.” It’s true — many words can be conveyed in a single image.

A graphic image has the power to distill big ideas into a bite-size visual. Like rote learning, graphic organizers can boost your reading understanding. Graphic images are often more suitable for expository or information type books.

It’s no surprise that presenting concepts and connections graphically helps you remember them.

It helps draw your attention visually to various features in your book. With a little imagination, mind maps and tables, it works well because it helps you to understand, memorize, and learn faster.

Here are a few examples of graphic organizers:

Tree diagrams – categories and hierarchies

Tables – compare and contrast data

Time and cycle diagrams – order of events (biology, life, water cycle)

Flowcharts – steps of a process

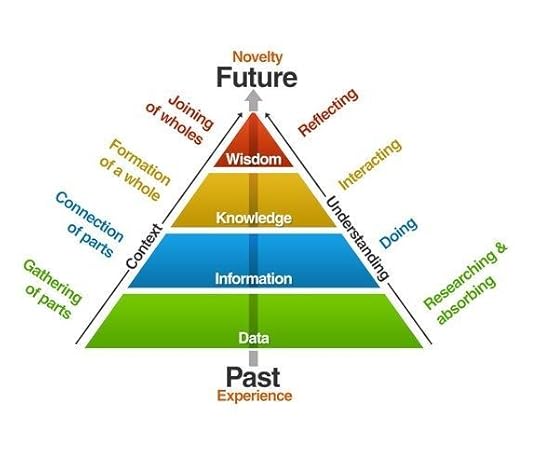

The hierarchy of knowledge is another reading comprehension idea to consider. It’s about the relationship between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. This becomes more important when you need to make a graphic organizer.

Source: https://kvaes.wordpress.com/2013/05/3...

10. Summarizing And Panning for Gold

Prior to summarizing it’s helpful to do intelligent highlighting while reading.

Decide beforehand how many key points you plan to memorize in the chapter. There’s rarely any need to do a total recall and try to memorize everything. That’s why proper goal setting helps you make a scope limit — it forces you to zoom in on the main ideas. Scott Young’s Ultralearning is great for more tips on this aspect of improving your reading missions.

Rereading can help to uncover any summary information that you mysteriously can’t remember. Like retelling, the process of summarizing condenses the main points into your own words. It’s like panning for gold. Once you’ve found some nuggets, you disregard the sand. Afterward, you can feel satisfied with a summarization mini-chapter.

Periodically, stop reading to contemplate on the main ideas in the text. This forces you to combine the key points into a clear outline. You could use new vocabulary as mental triggers when summarizing.

A good summary should paint an honest account of the big picture. The offshoot is that long passages appear less daunting.

‘’The more you share knowledge the more you memorize it. Share it, save it.’’

The process of sharing isn’t confined to your latest book. Try to practice making summaries of podcasts you listen to, informative videos you watch, or interesting conversations you have.

11. Memory Palace a Stairway To Heaven

The memory palace technique is a classical tool used in the ancient world. (Check out The Memory Code for the fullest possible depth of history.) It can boost understanding of books, since remembering information is a big part of why we read.

It’s a top recommended technique of memory champions and experts in the field. A Japanese man, Akira Haraguchi, recently demonstrated its power by memorizing π to 111,700 digits!

So how does the Memory Palace technique work?

Begin with association. You associate each piece of information you want to memorize with parts of a location you’re very familiar with; usually, your house is a good start.

Since you know this location very well, you place items you wish to memorize along a linear route through your house.

These are mental constructs you build in your imagination.

When you want to recall the information, you go through your mental route, and the information will be easily accessible.

When you add surprise characters and features to your memory palace, it helps make your Memory Palace even more effective.

You can also learn more about leveraging your imagination with Memory Palaces.

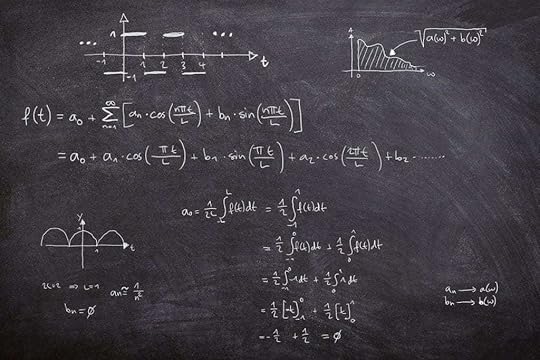

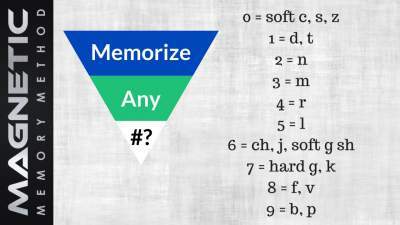

12. The Major Method — Where Numbers and Letters Collide

The Major Method is named after Major Beniowski. The earlier Major System (another term for it) was developed by Aimé Paris. He was world-renowned for his work in memorizing numbers. And thank goodness. His contributions have helped many thousands of people connect what we already know with what we don’t know.

Even with aphantasia, working with these techniques leads us to one incredible equation:

Exercising Your Memory = Improving Your Concentration = Better Reading Comprehension

The Major Method works by creating associations between numbers with sounds. Usually, a number is linked with a corresponding consonant like in this pattern below:

0 = soft c, s or z

1 = d, t

2 = n

3 = m

4 = r

5 = l

6 = ch, j or sh

7 = g, k

8 = f or v

9 = b or p

For example: to memorize the number 22 could be ‘nun’. Adult learners can use this sound-word association to memorize many numbers. All of this will come in super-handy when you know how to memorize a textbook.

Combined with a Memory Palace, you can use the Major to link numbers with other concepts you want to remember, like this:

A Memory Palace example showing the Major System combined with other mnemonic examples for remembering information.

13. Input-Output Lifestyle Choices

Lifestyle choices like taking care of diet, sleep, exercise, and meditation are often overlooked factors in reading (and learning in general).

Exercise: With people leading more sedentary lifestyles, health has never been as important. Regular physical exercise plays a big part in academic performance. A fertile mind enhances your creative energy.

Digital fasting: Mature learners are probably more adept at blocking out digital distractions. The aptly named smartphone is dumbing down our memory. Simply stepping away from devices can boost your focus and concentration powers. As a part-antidote to digital amnesia, reading leads to better brain health.

Diet: Our mind and body is a highly sophisticated organism. Yet some people live off processed artificial food and drink, and wonder why they’re ill so often. Eating more natural whole foods and avoiding refined sugars can help you become a higher performer.

Sleep: There is a good reason why airline pilots must get eight hours of uninterrupted sleep before flying. It leads to peak concentration and better overall performance.

Meditation: Meditation helps keep you on track with your vision. You can gain inner relaxation to keep you centered on what’s important. Whether it’s reading comprehension or memorizing numbers, meditation helps you to stay focused while everyone else falls by the wayside.

Bonus: The Four Levels of Reading

The team at Educational Technology and Mobile Learning put together an amazing infographic explaining the four levels of reading every student should know.

Source: https://www.educatorstechnology.com/2...

Your Next Chapter

Remember that frustrating feeling when you couldn’t grasp that new book? Having to ‘rewind’ through pages and paragraphs to eke out some understanding?

Instead of a dampened mood because you know you’re missing out on the valuable insight you need, reading comprehension strategies can help you race through the books you’ve always wanted to read.

It’s a fundamental skill that will serve as a tool to unlock any subject matter. You can truly leverage reading comprehension to achieve any goal like starting a business, passing exams, growing smarter, and contributing to brain health and concentration.

But you won’t make progress or increase your crystal and fluid intelligence without taking action. Pick one of the reading comprehension strategies in this post today, and start the new year with 20/20 vision to supercharge your reading comprehension skills.

The post Reading Comprehension Strategies: 13 Ways To Eliminate “Rewinding” appeared first on Magnetic Memory Method - How to Memorize With A Memory Palace.

January 15, 2020

Crystal And Fluid Intelligence: 5 Ways to Keep Them Sharp

Jane: “Did you hear Jonas’ speech? He spoke so well! Expressive and kept the audience enthralled. Very intelligent!”

Jane: “Did you hear Jonas’ speech? He spoke so well! Expressive and kept the audience enthralled. Very intelligent!”

Amanda: “Yeah, he was great! Creative, definitely! But intelligent?”

Jane: “It’s the same. You don’t need to be a mathematician or scientist to be intelligent.”

And so the argument continues.

But what is intelligence, really? Do you have fluid intelligence or crystal intelligence?

In this post, I’ll delve into the two types of intelligence (Fluid Intelligence and Crystallized Intelligence), examine how they work together, and talk about which one is more important. You’ll also learn 5 magnetic ways to build razor-sharp intelligence.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What is Intelligence?

What is Fluid Intelligence?

What is Crystallized Intelligence?

Can Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence Work Together?

Is Fluid Intelligence More Important Than Crystallized?

5 Magnetic Ways to Keep Your Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence Sharp?

What is Intelligence?

Many of the world’s most ‘intelligent’ scientists, researchers, and psychologists have been debating ad infinitum over a standard definition of intelligence.

For our understanding, intelligence is your ability to learn new information and use that knowledge to identify and solve problems.

You are deemed intelligent (read: smart) if you can use logic, reasoning, quick thinking, and planning to conduct daily activities effectively.

The good news?

You are not born with finite intelligence. You can boost your intelligence and thereby your social capital by using a proper memory method. (More about this later).

Are There Different Types of Intelligence?

Yes. Intelligence is subdivided into two distinct types — fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. They also go by the nicknames of gf and gc, where “g” stands for general intelligence.

The theory of fluid and crystal intelligence was first proposed by psychologist Raymond Cattell in 1963. He referred to the ability to reason as fluid intelligence, and the capacity to acquire knowledge as crystallized intelligence.

The concept was further developed by his student, John L. Horn, in the 1970s and 1980s. Their findings came to be known as the Cattell-Horn Theory of Intelligence.

The natural intelligence displayed by humans is very different from artificial intelligence (AI), which is intelligence demonstrated by machines. Our intelligence also differs in its cognitive capabilities from that demonstrated by open-source intelligence, which uses information collected from publicly available data sources. That’s not to mention our intelligence for developing concentration and memory through meditation.

A Fun Definition of Fluid Intelligence

Once, at a Paris hotel, my shower wasn’t working. I had checked in late at night, so there was no possibility of calling the plumber.

But I did manage to take a quick bath.

I used the Indian bucket bath method: where instead of a bucket and jug, I filled the drinking glass with water from the tap to pour over my body.

Genius, or what?

It was my fluid intelligence hard at work to come up with a novel solution to a unique problem.

Fluid intelligence is your ability to analyze, reason, and think out-of-the-box to find original solutions to new problems.

Your fluid intelligence uses logic in new situations or tasks, recognizes patterns, and incorporates abstract reasoning towards problem-solving.

Often, fluid intelligence is used when you solve math problems or jigsaw puzzles. You also use fluid intelligence when you start plucking on a guitar without prior training.

Your fluid intelligence does not depend on previously acquired knowledge. A person who is ‘street smart’ uses his fluid intelligence very effectively.

Fluid intelligence depends on your working memory, which is stored in the prefrontal cortex of your brain. It is governed by the anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex — regions of the brain responsible for attention and short-term memory.

More Examples of Fluid Intelligence

You use your fluid intelligence when you:

Identify patterns in logical reasoning questions,

Assemble a complex jigsaw puzzle using a picture,

Develop strategies or a game plan to solve problems,

Think outside the box when solving problems, or

Eliminate unwanted information when you conduct research.

There is bad news, though.

Fluid intelligence starts to decline with age, sometimes even as early as your 20s or young adulthood. Therefore, cognitive functions in elderly people may be reduced.

However, there are ways to keep it sharper and stronger even as you age. (We’ll come to that soon!)

Next, let’s look at crystal intelligence.

A Quick Definition of Crystal Intelligence

Crystal intelligence or crystallized intelligence is your ability to use knowledge and information previously learned over the years.

This type of intelligence is what you acquire through education and experience. Crystal intelligence gets cemented in the hippocampus, neocortex, and amygdala — parts of the brain that store and use long-term memories.

You use crystal intelligence when you do long division, or learn a new language. These tasks also require focused attention.

Ultimately, these terms are measurable. You can literally test and measure it through your grasp of vocabulary, grammar, reading comprehension, and your competence in quizzes and game shows.

Both internal and external factors impact the development of crystallized intelligence.

Internal factors include your innate curiosity and motivation to learn new things. External factors are the surroundings that you grew up in — your family, educational institutions, and society in general.

Examples of Crystallized Intelligence

Crystal intellect is at work when you:

Answer questions related to history or geography in a quiz. (For example, when did Columbus first arrive in America?)

Learn and speak different languages.

Know the exact ingredients used to prepare your favorite dishes.

Learn new words in your native language.

Memorize new maths formulae or facts

Conduct a surgery on a patient.

Remember the demographic statistics of a country you’re reading about.

The good news is: since crystal intelligence relies on the accumulation of knowledge, it is usually maintained with age. It peaks and declines much later in life as compared to fluid intelligence.

Interestingly, research shows that elderly people are valuable as workers as they make up for a decline in fluid intelligence with crystallized intelligence.

Cautionary note: While stronger intelligence may give you a head start in life, it may not prevent you from being affected by Alzheimer’s disease.

You may wonder: do these two types of intelligence cooperate?

Can Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence Work Together?

Turns out, fluid and crystallized intelligence are great team players.

Even though they are two distinct types of intelligence that cover different cognitive abilities of the brain, they work together more often than you might imagine.

For example, when you DIY a table, you use the woodworking skills your dad taught you years ago. This is your crystal intelligence. You figure out which raw materials to use, which tools to use, and how to follow a detailed design.

You also use fluid intelligence to reason and find solutions to any hurdles you face — for example, maybe a certain tool is not available and you need to find a substitute.

This solution is then transferred to long-term memory and becomes part of your crystal intelligence. If you face the same problem in the distant future, the solution would be retrieved from your long term crystal memory.

Use of Fluid and Crystal Intelligence When Cooking

Here’s another example of the interwovenness of fluid and crystallized intelligence:

When you cook a meal, which actually provides a decent brain workout), you utilize your crystallized intelligence to understand and follow the recipe. However, if you modify the spices or find substitutes for some ingredients according to your tastes and dietary requirements, you are utilizing your fluid intelligence.

These forms of intelligence seem quite different, but is one more important than the other?

Is Fluid Intelligence More Important Than Crystallized?

Not at all.

Both types of intelligence are equally important to function well in everyday life.

As I discussed earlier, fluid intelligence is directly related to being creative and innovative (i.e., your street smarts). Crystal intelligence, on the other hand, relies on being book smart.

However, today’s education system and our dependence on technology may deprive our brain of developing its natural aptitude for creative problem-solving.

Educational institutes even resort to the Wechsler Intelligence Test or other IQ tests to determine the cognitive skills in students based only on crystal intelligence. Many cognitive training tasks also give more importance to developing crystallized intelligence.

However, I believe the goal should be to strengthen your overall intelligence — be it crystal or fluid.

Crystal intelligence is closely linked to long-term memories. Fluid intelligence is, however, associated with short-term memory or working memory.

Research says that if working memory is deficient, the ability to acquire knowledge and related skills will be limited. A study by Susan Gathercole and Tracy Alloway showed that “working memory functions as a bottleneck for learning in individual learning episodes required to improve knowledge.”

But what does that mean?

In simple terms: you need to develop your fluid intelligence to enable your crystal intelligence to work well!

Let’s look at how you can do just that.

5 Magnetic Ways to Sharpen Your Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence

Here are five great ways to improve both types of intelligence.

1. Create Memory Palaces

When you build memory palaces using the Magnetic Memory Method, you are using both fluid and crystal intelligence in ways that enable you to improve them.

The Magnetic Memory Method Memory Palace is a powerful way to train the brain regions that govern your fluid and crystal intelligence.

It’s also a better method for remembering and learning information than using other techniques like mind mapping on its own because you’re innovating and drawing upon existing mental content at the same time.

Plus, any time you can combine intelligence and memory strengthening, you get holistic improvement of all levels of memory. You can move short-term memory into long-term memory faster (and permanently) with a minimum amount of practice.

2. Get Creative

It is believed that to be creative, you don’t have to come up with original ideas all the time. You’re creative just by finding new connections between existing ideas.

This could be as simple as finding a new route to go to work, starting new eating habits, or adding new ingredients to a pasta recipe you’ve stuck to for years.

Or, if you’re an artist, simply abandon your tools for a while and wander outside or travel to a new place. Inspiration for your next masterpiece may strike you from unexpected places.

And sometimes constraints fuel creativity, so set yourself time and space limits to complete a project.

3. Challenge Your Brain

Technology has made everyday life so easy for all of us — so switching off is a great way to challenge your brain.

Remember the saying “use it or lose it” and unplug from your devices every once in a while. For instance, navigate to a new landmark in your city without a GPS.

Seeking new experiences, learning new skills, and staying busy with hobbies and people are great ways to keep your fluid and crystal intelligence sharp.

You might also learn a new language, watch a new genre of movies, read on a topic that is alien to you, or just try using your non-dominant hand for a few everyday activities.

4. Meditate Regularly

Mindfulness meditation is a way to engage new neural pathways in your brain. Research has proven that this neurostimulation can transform your body and brain positively.

This form of active brain training can improve your focused attention, long term retention and recall, and your working memory capacity, which are all important aspects of your fluid and crystallized intelligence.

5. Get a Good Night’s Sleep

Want to get a sharper memory? Get more sleep.

As counterintuitive as this may sound, sleep can sharpen your intellect. In fact, sleep is one of nature’s most ignored memory-boosters.

If you’re well-rested, you stay alert and attentive throughout the day — which positively affects your ability to retain more and learn new things like riding a car or learning a new language.

Boost Your Intelligence, Magnetically

Memory science is important and worth reading, but you are the ultimate scientist in the laboratory of your own memory and intelligence.

Why not get cracking at a new intelligence-boosting experiment with me today? Register for my free course, and I’ll send you my free memory improvement worksheets and videos.

The post Crystal And Fluid Intelligence: 5 Ways to Keep Them Sharp appeared first on Magnetic Memory Method - How to Memorize With A Memory Palace.

January 14, 2020

How to Memorize a Speech Fast (Without Sounding Like a Robot)

Imagine this: you’re standing up in front of an audience and giving an important speech.

Imagine this: you’re standing up in front of an audience and giving an important speech.

Now tell me, how do you feel? Are your hands sweaty or your knees shaky? Is your stomach tied up in knots and feeling a bit queasy?

If you’re anything like me during my undergraduate years, maybe you even have a phobia of public speaking. Yes, it’s true. I once had a terrible aversion to giving speeches, because I took a medication for manic-depression that made me shake really, really badly.

Once, in a course on romantic poetry, I was supposed to give a speech. My hands shook, my papers rattled in my hands, and I couldn’t concentrate on my delivery of the speech… much less expressing my familiarity with the topic at hand!

Instead, I ended up frustrated and embarrassed. It was one of the most horrible moments of my scholarly career to be shaking so badly and yet have so much to say.

And to top it all off, the professor wouldn’t take me at my word — I had to go to the Behavioural Sciences Building to get a letter from the psychologist explaining that I could have an alternate assignment instead of being required to give the speech. This bad experience led to a fear and phobia of giving speeches that lasted for quite some time.

But here’s the good news: even if you have a fear of public speaking – most people do – there’s still hope. With the help of memory and a few other tricks I’ll teach you today, you can overcome your fear.

And I’ll let you in on a secret. Now, when I give a speech I really have a lot of fun!

So are you ready to kick your fear of public speaking to the curb and have fun with it instead? Let’s dive right in and take a look at how to memorize a speech — and how memorizing can help you overcome your public speaking fears.

Want to skip ahead to a particular section?

Memorizing a Speech Without Losing Your Place

How to Memorize a Speech: Tips and Techniques

Tip Number 1: Be Prepared

Tip Number 2: Relax, Relax, Relax

Tip Number 3: Don’t Make it a Big Deal

Tip Number 4: Know Your Body

Tip Number 5: Do Table Reads

Memory Palace Alternatives

The Best Way to Memorize a Speech: Create a Memory Palace

How to Memorize a Speech: Step by Step

Real-Life Examples of How to Remember a Speech

Recommended Reading for Memorizing a Speech

FAQs about Memorizing a Speech or Presentation

Have Fun Memorizing a Speech

You might be thinking… “but will your approach work for me?”

I can honestly say — yes! I’ve seen this method work not only for me, but also for clients of mine. Here’s one example:

Michael DeLeon wrote the other day and said:

“I’ve been training myself in the techniques of the Magnetic Memory Method. I’ve given two speeches that were, by far, the easiest for me to give because of the Magnetic Memory Method. I felt no pressure. I could relax and deliver the speech I wanted to give because there was never a fear of ‘I would lose my place.'”

So are you ready to learn some tips for memorizing a speech? Let’s start with a common fear: losing your place.

Memorizing a Speech Without Losing Your Place

When we talk about how to memorize a speech, one of the first things people often ask is what to do when you get lost. In this post, we’ll cover how to find your way quickly back, as well as a host of other issues that can arise during your speech.

We’ll also talk about Steal the Show: From Speeches, to Job Interviews, to Deal-Closing Pitches, How to Guarantee a Standing Ovation for all the Performances in Your Life, a great book by Michael Port that I’ve learned a lot from, as well as some tips I learned from my mentor about giving speeches.

The short answer is: a Memory Palace can help you be fearless, focused, and able to track back if you ever do lose your place. The longer answer? Keep reading!

To make the most of this post, take notes as you read, then start to carve a path forward to where you go out and give some kind of speech (even if it’s just to your friends and family).

We’ve got an action-packed post waiting for you, so let’s get started.

How to Memorize a Speech: Tips and Techniques

Before we talk through my top tips, let’s get one big question out of the way: what’s the point of learning to give (and memorize) a speech? Whether or not you’re using a memory technique, why do you want to learn how to do it?

Here are a few benefits to being a great public speaker:

It’s a highly marketable skill.

There are lots of companies that need someone to be able to present the value they offer – their expertise, unique selling proposition, value for the market, etc – and why customers should pick them. It’s the same for you — you want to be known as the person a company wants to hire, the one they want to promote, the one they want to give a raise.

Public speaking displays your expertise.

Your ability to speak coherently and clearly is a key indicator to both your employer and clients that you know your stuff. When you can speak from the top of your mind without hemming and hawing or stuttering, it lets your knowledge shine.

Stepping on stage develops courage.

Getting comfortable with public speaking takes practice — and getting out there and starting to give speeches (even if it’s just to a friend or two at first) will begin to build your courage muscle. It’s a win-win.

Speaking shows your personality.

As you practice giving speeches, you’ll begin to develop your own personal presentation style. And the more comfortable you get, the more your personality will shine.

Giving speeches helps build relationships.

Getting out into the community allows you to connect with people in both your personal and business networks. And if you’re still in school, it can help you build connections with your teachers and your fellow students.

Public speaking sets you up as an expert in your field.

When you’re the one up on stage, it’s clear to the audience that you know what you’re talking about. You can prepare the road ahead by being known as the expert who has the courage to get up on stage and share their knowledge. Just look at Sunil Khatri’s speech success story.

It helps you deliver results to other people.

Right now, your audience doesn’t have a particular set of knowledge. When you get up on stage, you’re able to give them that knowledge — and package it in a way that helps them quickly absorb it. Plus, you can do so in a way that encourages them to take action, because they’ve seen you demonstrate how valuable it is from the stage.

Speaking can help you build your memory as you learn.

Learning to memorize a speech will help you build your memory as you go. Even if you do need notes in the beginning, you can still improve your memory as you practice your speech.

Bonus: it’s fun!

It’s not only a valuable skill, but being able to jump up on stage and speak off the top of your mind is actually a lot of fun!

Now you know the benefits of memorizing a speech, let’s take a look at a few tips to help you along the way.

Tip Number 1: Be Prepared

The number one best technique of all is to be prepared.

This means: do your research and have the knowledge in your head that you’re presenting on. This might be obvious, but a lot of people think they can skip this step.

If you’re nervous or worried, that sense of fear often comes from the fact that you don’t know your topic well enough. At the end of the day, be prepared with solid research and actual knowledge about your subject…

Because the number one memory tool you have — is to not have to use memory techniques.

You’re here to memorize a speech, but the best way to do that is to know what you’re talking about. It will help you avoid your fears about getting lost when you know your subject backwards and forwards.

Part of giving good speeches from memory is preparation — as you prepare, memorize the key information as you go along. There are a number of ways to do this:

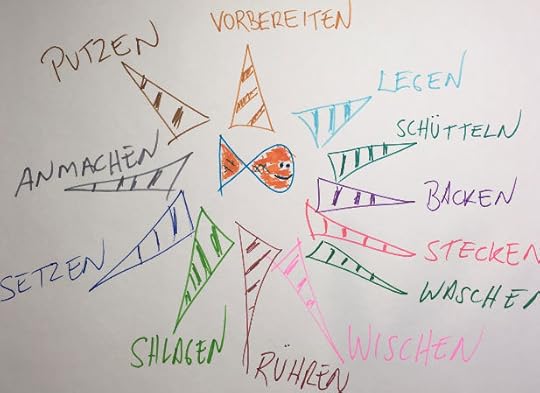

Use a Mind Map

Mind mapping helps you prime your memory from the very beginning, by giving it structure in space.

Imagine you’re creating a mind map — you have your central image, which primes your mind to dig deep into your memory and create a mental image around the core topic, by name. You can also use a key word that’s big, bold, and centered in your attention.

This example Mind Map was created for one of my live stream presentations. I usually juggle for a few minutes before giving a speech to get my creative juices flowing.

This allows you to think in imagery and images placed in space, and also the connections you can make by having multiple key words arranged in space.

You can also turn a mind map into a Memory Palace.

Consider Content Mapping

If you decide to memorize your speech verbatim, this is another kind of mapping that can help you with your beats.

But what do we mean by beats? When you memorize verbatim, you may want to remember things like:

Where your pauses are,

Where on the stage you plan to turn and look at a particular part of the audience,

When you want to pull a prop from your pocket, or

Any other physical cues.

You might even plan to give a speech with another person and need to remember where their lines begin.

Hat tip to Steal the Show by Michael Port for this idea.

Read Additional Books

Once you create your original mind map, then you might consider reading two or three additional books on the topic.

For example, I recently did a livestream on the topic of how to memorize a speech. As part of my preparation, I read not only Michael Port’s Steal the Show, but also the Rhetorica ad Herennium and other books on rhetoric and speaking by authors like Matthew Clark and Dan Kennedy.

Know Your Audience

One fun way to engage with your audience is to know and mention the names of your host and audience. When I give talks on memorizing names, I make it a point to memorize every name in the room — and then I address audience members by name as I give my speech.

But even more important is to tailor your presentation and speech to that particular audience. This may mean memorizing things about the audience, or things about the individuals who will be present, so you can respond on the fly.

You won’t initially have the kind of information you need to do this, but it’s easy to find. Reach out to the person who invited you to give the speech – or ask your teacher or professor – and ask them what considerations they would like included in your speech.

It’s very powerful to tailor your speech to the audience and their specific interests or concerns.

Train Under Pressure

When you’re in the middle of a speech, you ideally want to keep moving forward — even if you make mistakes or something unexpected happens.

When you memorize your speech and train yourself to give it under any circumstances, it can help you find your place when the unexpected happens. You can then quickly find where you were and keep moving forward.

Now that you’re prepared, it’s time to let your hard work pay off.

Tip Number 2: Relax, Relax, Relax

The most important step of all is relaxation, and being willing to let go of your expectations.

When the light goes green and you’re live you can no longer control the outcome — but you can practice not being in control very early on. You do this through relaxation.

You will relax while you:

Prepare your research,

Memorize your speech,

Practice reciting what you’re going to say from memory,

Deliver your speech (by being relaxed ahead of time), and

Analyze how the speech went.

The more relaxed you are during each of these stages, the more you’ll be able to effectively analyze how your speaking engagement went. This gives you the chance to think through the results in a clinical fashion and improve, rather than judging yourself on your performance.

But how do you relax at each stage of preparation and memorization? There are a few techniques you can use.

Box Breathing

This is a breathing technique that’s widely attributed to a former Navy SEAL, who used the skill set to stay calm in combat situations.

To use this technique, think of a square and follow along with your breath.

Inhale to a count of five,

Hold the breath in for a count of five,

Exhale to a count of five,

Hold the breath out for a count of five, and then

Repeat as necessary.

This technique is really good for activating your parasympathetic nervous system and giving you some space between you and your monkey mind. The more you’re able to relax, the more you can be present to what’s happening — instead of overthinking.

You might wonder: why does the monkey mind go on and on?

Well, it’s worried what people are going to think about you! It’s worried about what happens if you make a mistake. It’s worried about what happens if people think you’re going to make a mistake.

Prepare to Make Mistakes

So here’s the deal… I guarantee you’re going to make some kind of mistake. But — it’s not really a mistake if you don’t pay attention to it. If you’re relaxed and you just move on, the audience is less likely to notice that you made a mistake than if you get flustered and lost.

Everyone stumbles over their tongue every once in a while, and the more you speak the more it will happen to you. The way you overcome mistakes is to be relaxed and just keep going.

Remember: it’s all about practice.

Meditate

I highly recommend meditation for anyone preparing to give a speech.