Matthew Dicks's Blog, page 384

August 20, 2014

Boyhood made all the difference for me.

My friend came over last week and installed a faucet under my sink. This is not the first time I have asked him to help me with a repair. He once spent four long hours on a Friday night unclogging the same sink with me.

He has also repaired two lamps for my daughter, though both times, the repair required the replacing of a light bulb.

My friends can repair things. Build things. Diagnose problems. They can use tools. Identify tools. Repair tools.

I cannot. It often leaves me feeling like a fool.

I saw the movie Boyhood last night. It was an extraordinary film that brought back many memories from my boyhood. Not many good ones.

Part of my inability to fix and repair things is a result of an innate lack of visual-spatial acuity. A school psychologist once administered a new cognitive test on me in order to practice and became irate with me for “screwing around” and not trying my best.

I was trying my best. I was completing a section that required me to rotate, reverse, flip and otherwise manipulate shapes.

I had no idea what I was doing. I barely understood what she was asking me to do. I finished the subtest with the score equivalent to an average seven year-old child.

I was not surprised.

But it occurs to me after watching the film that an even greater reason for my inability to work with my hands was simply the way that I grew up. My father and mother divorced when I was a little boy, and my father quickly drifted out of my life entirely. My mother remarried, but my stepfather had little interest in raising me. He didn’t teach me to play sports. Didn’t teach me to fish or pitch a tent or even mow a lawn. Didn’t teach me to use tools.

I didn’t have a father putting a hammer into my hand and teaching me how to bang in a nail. I didn’t have someone explaining to me how things works. I spent most of my childhood on my own, figuring out things for myself.

Then I graduated from high school and began a decade of turmoil and struggle. I moved in with a friend attending college and worked 50-60 hours a week in order to survive. My parents never visited me or even called. Unless I went home to visit, I never heard from them.

Two years later, my stepfather divorced my mother.

When my friend graduated from college and moved to Connecticut, I was homeless. I lived in my car. Eventually, I was taken in by a family of Jehovah Witnesses, working 80-90 hours a week while awaiting trial for a crime I did not commit.

When I was finally found not guilty after almost two years, I moved to Connecticut, chasing my friend and a girl, and I quickly found my way to college. I attended school fulltime while working 40-50 hours a week managing restaurants and tutoring in order to make ends meet.

When I finally graduated from college with degrees in English and elementary education, I was 29 years old. I was starting my teaching career. For the first time in my life, I was not struggling to keep my head above water. Barely keeping food on the table.

I wasn’t until I was almost 30 years old that I had genuine stability in my life.

When was there time for me to learn to fix a car? Who was there to teach me? I grew up without an Internet. Without tools. Without an innate ability to see how things fit together.

I saw that boy in Boyhood, and in many ways, I saw myself. I watched a boy whose life was filled with transition, trauma, uncertainty, and solitude.

My friends make fun of me for not knowing how to make simple repairs. They tease me for requiring help with the most basic things. And when I ask a friend to repair a lamp that only requires a bulb change (twice), I deserve every one of their insults.

But I also know that I spent the first 30 years of my life just trying to keep my head above water. While most of my friends were off at college after high school, I was struggling at times to feed myself. There was a winter when my roommate and didn’t turn on the heat because we couldn’t afford it. I lived in my car. In a pantry. I spent a summer sleeping in a closet. There were many, many days spent cold, hungry, frightened, and alone.

The idea that I could’ve learned how to tune up my car or take apart kitchen sink is crazy.

For the past 15 years, there has been greater stability in my life. I have a home. A career. A family to support me. I haven’t had to work 80 hours a week or work full time while completing two college degree programs.

There has been time to learn the things I never learned.

But imagine being a 30 year-old man who has never used a socket wrench in this life. Never drilled a hole in plaster. Never built a single thing with his hands.

Yes, I could start learning, and to a degree, I have. There are things that I can do with my hands today that would’ve been unimaginable to me just ten years ago. Last week I repaired a door and a toilet seat in my house and was unreasonably proud of myself for my efforts.

But a person also reaches a deficit in learning that can seem insurmountable. The multitude of lessons missed over the years begin to pile up. They begin to create exponential deficits. Eventually the things that you can’t do become just as much a part of your identity as the things you can do. When you spent the first 30 years of your life as one person, it’s hard to envision yourself as another.

I listen to my friends talk about their childhoods with their fathers. I hear stories about how they followed their dads into basements to repair furnaces and plumbing. Crawled under cars to inspect exhaust systems. Built tree houses in the backyard. When I listen to them talk, it’s almost as if they are speaking a foreign language.

When they come to my house to help me, I try to watch. I ask questions. I want to learn. But I also know that I am attempting to mitigate decades of learning that was missed.

When my friend came over to install the new faucet, I was able to turn off the water in my house. I held the faucet steady while my friend worked underneath the sink. I handed him tools. I asked questions. I watched him solder a corroded pipe. I tried hard to learn while trying harder to stay out of his way and not waste his time.

In the end, I didn’t help very much. I learned a little. This is how it has always been for me. Ask a friend for help. Assist in any way I can. Avoid getting in the way. Try to learn as much as I can. Express my appreciation.

This is not the same as a father showing his son how to swing a golf club or change the oil in a car or build a tree house. It never will be.

I’ll keep asking for help. My friends will continue to tease me, and oftentimes, justifiably so. It’s okay. It’s who I am.

And I will continue to listen to them talk about fathers who taught them to dribble a basketball and coached their Little League teams and helped them buy their first car or showed them how to install a dishwasher. Sometimes I meet these men. These fathers who did their jobs. Stood by their sons. Taught them what they needed to know.

I shakes the hands of these fathers and stand in awe at the very idea of fathers and sons whose lives are connected and intertwined.

It’s something I have never known.

I hope my friends know how lucky they are.

Can you imagine a better way to start the day?

My boy likes to read, which is great. He can’t actually read yet, but you know what I mean.

It’s not quite as great when you’re trying to put him down for a nap and he demands. “Mmm book! Mmm book!”

But when I crept into his bedroom yesterday morning and found this, my heart swelled to three times its size:

August 19, 2014

What is the best way to invest one dollar?

Melissa Batchelor Warnke of The Morning News asks: Say you had a buck in your hand: What would be the best way to invest it?

The piece features answers by two dozen people—a JP Morgan associate, a sex worker, a pastor, a living statue, a marine, and many more.

There are some great answers. My favorites come from the professional escort and the founder of DreamNow.

There are some stupid answers, too.

I’ve been struggling with three possible answers to this question, but after much internal debate, I have finally settled on one.

My runners-up include:

Take my children to a penny candy shop. Allow them to purchase as much candy as possible. Walk to a park and devour the candy while we play.

Find a company where I would love to work. Ideally a startup of some kind in a field that intrigues me. Call the CEO, the human resources director, or whoever else is responsible for hiring. Offer to buy them a cup of coffee in exchange for 30 minutes of their time. Attempt to win them over and land a job.

But my winning answer is this:

Purchase a notebook. Begin writing my next novel.

My wife’s answer was also excellent.

Download a song that is guaranteed to make me happy regardless of the circumstance or the number of times played.

Apparently there are two such songs:

Van Halen’s Jump and Hall & Oates You Make My Dreams Come True.

My book club once featured skinny dipping. This book club has a big time college football player for a member. I think they win.

I’m not a big college football fan. I don’t have an allegiance to any college football team. But wide receiver Malcolm Mitchell may have turned me into a Georgia Bulldogs fan with his recent foray into, of all things, a book club.

It’s a great story. I can’t wait to show this video my students at the beginning of the school year. You must watch.

Go Bulldogs.

August 18, 2014

Stuff I don’t know: Flowers

It will not come as a surprise to many that I don’t know a lot of things. But in addition to not knowing many things, there are also many things that I don’t know that everyone else seems to know, making me feel especially ignorant.

Rather than concealing my ignorance, I’ve decided to keep a list of these things that I don’t know and, when possible, determine the causes of my ignorance and perhaps rectify the situation.

As one of my friends has said, “I live out loud.”

_________________

I don’t know flowers. With the exception of roses and tulips and dandelions, I can’t identify a single flower with any certainty.

My five year-old daughter can already identify more flowers than I can.

I don’t know where everyone acquired this vast storehouse of knowledge about flowers. Perhaps my ignorance is born from my propensity to ignore detail, or maybe it’s the result of my lack of interest in flowers. I can identify many types of trees thanks to my Boy Scout training, but I just checked my Boy Scout Handbook.

Eight pages on flowers. More than two dozen images of flowers.

Just as many pages covering flowers as there are covering trees.

I don’t think I need to make a concerted effort to rectify this bit of ignorance, but perhaps I can ask my daughter to teach me about flowers whenever she has the chance.

Make it a father-daughter thing.

August 17, 2014

Happy boy

Running back and forth between Mommy and Daddy while waiting for our table was enough for our son. He needed nothing more.

How lucky we are.

Plants are smarter than we ever imagined. Eating them is no less cruel than eating a cow. And cows taste better.

I have always secretly hoped that someday we would discover that plants are just as sentient as animals, and as a result, the aggressively judgmental, overly proselytizing ethical vegans of the world would be forced to come to terms with the fact that when it comes to food, they are no less murderous than the cow and chicken-eating people like me.

It’s getting harder and harder to deny that plants are a hell of a lot smarter and more aware of their surroundings than we ever thought.

Certain plants are capable of evading enemies and discerning friend from foe.

Plants can communicate with each other:

Plants respond to gravity. Light. Chemicals. They move. They network. They sleep. They play:

Natalie Angier, writing for the New York Times, points out that plants are chemical factories that are capable of calling for help. Warning their neighbors. Bait and trap their enemies. Plotting the demise of their attacker.

Angier challenges the moral high ground that ethical vegans have so righteously ascended. She writes:

Plants no more aspire to being stir-fried in a wok than a hog aspires to being peppercorn-studded in my Christmas clay pot. This is not meant as a trite argument or a chuckled aside. Plants are lively and seek to keep it that way. The more that scientists learn about the complexity of plants — their keen sensitivity to the environment, the speed with which they react to changes in the environment, and the extraordinary number of tricks that plants will rally to fight off attackers and solicit help from afar — the more impressed researchers become, and the less easily we can dismiss plants as so much fiberfill backdrop, passive sunlight collectors on which deer, antelope and vegans can conveniently graze. It’s time for a green revolution, a reseeding of our stubborn animal minds.

I’ve said it before: It’s remarkably arrogant for us to think that we fully understand the true nature of any living thing, including plants. To simply assume that the carrot you are eating is incapable of experiencing thought or pain or existential suffering is foolish. As scientists are continuing to discover, plant life is capable of far more sentience than we could have ever imagined.

So eat up, my ethically vegan friends, while there is still time. It won’t be long before we discover that the acorn that smacked you on the head was purposely thrown by an oak tree getting revenge for it’s leafy brethren.

August 16, 2014

She’s worried about her husband’s diapers. She should be more worried about her child’s early morning routine.

Slate’s Dear Prudence answers a question from a reader whose husband is a lifelong bed wetter who wears a diaper and rubber pants to bed each night. The reader is worried about the possibility of her children discovering their father’s secret and wants to know if they should be proactive and tell the kids before they find out for themselves.

First, let me say that this woman deserves a great deal of credit and at least a nomination for Spouse of the Year. While it’s true that if you love your spouse, this would not be a deal breaker, but they way in which she has accepted and even embraced the situation is remarkable.

She writes:

We are both completely comfortable with his bed-wetting and diapers and it’s actually fun getting him ready for bed. I took over getting him diapered and its really made us closer.

This is a woman who you hold onto at all costs.

The thing that Emily Yoffe rarely does in her role as Prudence is comment on issues other than those specifically addressed in the letters she receives. While I have no quibble with the advice that she offers this woman (it’s a private matter that only needs to be explained if discovered), I can’t help but think that the most important sentence in the letter (that Yoffe ignores) is this:

So far, the 8-year-old has not discovered the secret, but routinely comes to our room at 4 a.m. after waking up.

This is the real problem. Your eight year-old should not be routinely waking up at 4:00 every morning (this coming from a person routinely awake at 4:00 every morning), and he absolutely, positively shouldn’t be coming into his parents’ room at that hour.

While we can’t control the time that our children wake up (I’ve tried), we can avoid rewarding them for waking up early by insisting that they remain in their own bedrooms and not disturb our sleep.

At three years-old, this is admittedly hard, and possibly impossible.

At five years-old, it’s probably still difficult.

But an eight year-old can be stopped. An eight year-old has reached the age of reason. An eight year-old understands consequences. An eight year-old can and should be stopped.

Forget your concerns about your husband’s diapers. Your child is not sleeping enough and is being rewarded for waking up too early. He is disturbing your sleep, as well, which is no less precious,

Sometimes the perceived problem and the real problem are two entirely different things.

Working hard for the money: 2014 update

A few years ago, I posted a list of all the jobs I have held in my life in chronological order.

It was an interesting exercise that I highly recommend.

Things have changed since I first posted the list, so here is my updated list:

1. Farm laborer, Blackstone, MA: When I was 12-years old, I began working for Jesse Deacon, an aging farmer in need of some help. Every Saturday, I would spend 4-6 hours loading hay onto trailers, mucking stalls, repairing fence lines, and other typical farm chores. I earned $50 a day for the work and was happy to get it.

2. McDonald’s restaurants, Milford, Norwood, Brockton, Hanson, Bourne, MA: My illustrious and rather sordid career with McDonald’s began when I turned 16-years old. My friend, Danny Pollock, heard that the McDonald’s in Milford, MA was hiring, so even though Milford was more than 30 minutes from my hometown of Blackstone, Danny and I drove out there for interviews and were hired on the spot. We started out just above minimum wage, $4.65 per hour. Danny didn’t last long and eventually became a dishwasher across the street, but I stuck, eventually being promoted to manager when I was 17-years old. I can still remember sitting in history class with my professional development binder from McDonald’s, studying for my management exam when I was supposed to be reading about the Great Depression. I stayed with McDonald’s after graduation (college was not an option for me after high school), eventually moving to Norwood with my store manager and later to Brockton, Hanson (where I opened a new store), and Bourne, where I was eventually fired after being arrested for grand larceny.

3. Cobra Marketing, Foxwood, MA: After being fired from McDonald’s, I was hired by Cobra Marketing, a company that marketed consumer products to employees at a variety of businesses throughout the state. I began as a salesman, dropping off samples to businesses early in the week and then returning for orders at the end of the week and earning my salary strictly through commission. I worked in the book division, which meant that the samples I was dropping off to businesses were all books. Eventually I was promoted and was placed in charge of a sales team.

4. Cobra Marketing, Washington, DC: Following my promotion, I was sent to Washington, DC for four months to establish a new office for the company. A team of eight people from Connecticut spent the summer of 1993 living in a two-bedroom apartment in College Park, Maryland. During this time we hired, trained, and put the systems in place that would allow the business to function on its own once we returned to Massachusetts. Having lost the coin toss for one of the two beds in the apartment, I spent the four months sleeping on an air mattress in a walk-in closet with a girl named Kim. It was during this time in Washington that I met Ted Kennedy, shook Cal Ripken’s hand, and was mugged at knife point.

5. South Shore Bank, Stoughton, MA: After returning to Massachusetts and resuming the sales routine, I decided to move on and was hired to work as a teller by South Shore Bank (later Bank of Boston), the same bank that would later testify against me during my grand larceny trial.

6. McDonald’s, Brockton, MA: Needing to pay for my legal defense, I also went to work for a privately-owned McDonald’s restaurant in Brockton, across town from the company-owned store where I had worked years before. My girlfriend at the time was working in the company-owned store, as were the Jehovah Witnesses with whom I was living. I would work at the bank from 7 AM- 4 PM and would then manage the closing shift at McDonald’s, working from 5 PM until 1:00 AM. I did this for eighteen very long months until my trial concluded and I was found not guilty. It was while managing this restaurant that I was robbed at gunpoint.

7. Legal Copy Service, Hartford, CT: Having been found not guilty at my trial, I was free to leave the state, so I moved to Connecticut, chasing a girl and my best friend. I landed my first job at a legal copy service in downtown Hartford. Beginning as a machine operator but unable to stand the monotony of the work, I eventually managed the company’s delivery service until finally quitting after less than four months on the job.

8. The Bank of Hartford, West Hartford, CT: Needing to earn more money, I went back into banking, landing a job at the now defunct Bank of Hartford on Park Road in West Hartford. I was eventually promoted from teller to customer service representative but left after a year when I decided to go to college and was in need of a more flexible schedule.

9. McDonald’s, Hartford, CT: Negotiating a decent salary and a flexible schedule because of my experience and expertise, I went back to work for McDonald’s, this time managing a company owned store on Prospect Avenue in Hartford. I would work from 5 AM- 1PM on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, plus ten hours a day on Saturday and Sunday while going to school, first at Manchester Community College and later at Trinity College and St. Joseph’s College.

10. Trinity College, Hartford, CT: While attending Trinity College, I was hired as a writing tutor in the school’s Writing Center. I would spend about three hours each evening teaching freshmen to write a clear and grammatically correct sentences and helping seniors to edit and revise their thesis papers. My name actually appears in the acknowledgements of several thesis papers in the Trinity College library.

11. Jam Packed Dance Floor DJ’s: It was while I was attending Trinity and working for McDonald’s that Bengi and I went into the disc jockey business, entertaining at weddings throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts. We went from booking three weddings in 1997 to 41 weddings in 1998 and have been going strong ever since.

12. Kindergarten tutor, Wethersfield, CT: When I began student-teaching in the spring of 1999, I left McDonald’s for good in order to accommodate the full-day schedule that student-teaching demanded. To supplement the loss in salary, I began tutoring underprivileged kindergarten students for the town of Wethersfield for a period of about six months. The time that I spent with those kids convinced me that kindergarten was not for me.

13. Substitute teacher, New Britain, CT: Having completed my student teaching in early May, I went to work as a full-time substitute teacher in New Britain, the town in which I had done my student teaching. I worked nearly every day until late June, teaching everything from bi-lingual kindergarten to high school physical education.

14. Teacher: In the summer of 1999, I was hired to teach at my current school. I’ve been there ever since.

15. Minister: After becoming ordained by the Universal Life Church, I began conducting wedding ceremonies and baby naming ceremonies as a minister. Many of the wedding ceremonies (but not all) have been booked in conjunction with the DJ business, and I have since branched out into other areas of ministerial work as well. One family actually refers to me as their “family minister”.

16. In 2007, I sold my first book, Something Missing, to Doubleday Broadway and became a professional author. I had made a little money publishing pieces in newspapers, magazines and professional journals prior to the purchase of my novel, but it had never amounted to much. Since then I have also published Unexpectedly, Milo, Memoirs of an Imaginary Friend, and the upcoming The Perfect Comeback of Caroline Jacobs. Writing has become a full time career for me.

17. Life coach: After learning about the existence of life coaches from one of my wife’s friends, I decided that I was eminently qualified for the job. I began my career as the pro-bono life coach for a colleague and friend but have since been hired by my first client.

18. Spean Up: In 2013 my wife and I launched Speak Up, an organization dedicated to the art of storytelling. We produce shows in conjunction with Real Art Ways, teach workshops to people interested in improving their speaking and storytelling abilities, and have recently begun schedule shows at outside venues.

19. Tutor: I have tutored off and on for several years but have recently been hired by clients on a more long-term, regular basis.

20. Professional speaker: As a storyteller, I am often paid to take the stage and perform. In addition, I am a member of the Macmillan Speaker’s Bureau and have begun to be hired to speak publicly on a number of topics, including education, motivation, and storytelling.

21. Columnist: In the spring of 2013, I was hired as the humor columnist for Seasons magazine.

There was a time when my blogging brought in a little money each month when I was serving advertising, but nothing has panned out to the point of real profit.

I still have dreams of becoming a professional best man (I have been offered jobs four times but was forced to decline because of distance), a gravesite visitor and a professional double date companion (with my wife). I would also like to earn more money blogging and am currently working on making that happen.

But for now, I’m pretty happy as a writer, a teacher, a life coach, a DJ and an occasional minister.

Had you asked the ten-year-old version of me what I wanted to be when I grow up, I would’ve said teacher and writer. For a long time, I said that I wanted to “write for a living and teach for pleasure.”

I’m not there yet, but it’s not as far away as it used to be, either.

August 15, 2014

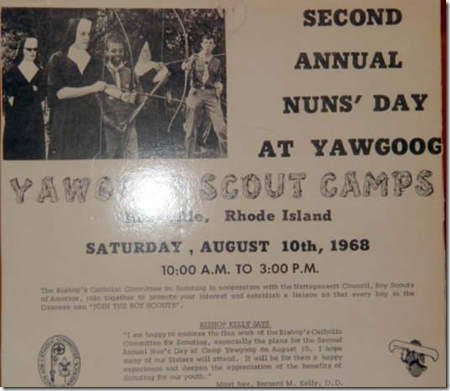

“Where do you get your ideas?” is an understandable but impossible-to-answer question for authors. But “Nuns at Scout camp” will be one of my answers someday.

I’m often asked where I get my ideas for books, which is an understandable but impossible question to answer.

There is no well of ideas. There is no secret formula. There is no one answer to that question, as much as fledgling writers seem to want there to be.

Simply put, I hear something. I read something. I see something. The flicker of an idea is born.

Something Missing was born from a conversation with a friend over dinner about a missing earring.

Unexpectedly, Milo began with a memory from my fourth grade classroom.

Memoirs of an Imaginary Friend was born from a conversation with a friend and colleague while monitoring students at recess.

My upcoming novel, The Perfect Comeback of Caroline Jacobs, originated with a story that my wife told me about her childhood just before falling asleep.

My unpublished novel, Chicken Shack, began with a dare.

All of these are simplifications of the actual origins of these novels. There are more complex stories behind the origin of each book. In all cases, additional ideas were grafted onto the original idea to create a more complex story.

But in terms of the initial spark, that was how each story began.

Which leads me to this poster, which is displayed in the Yawgoog Heritage Museum at Yawgoog Scout Reservation, the camp where I spent many of my boyhood summers.

I suspect that someday in the future, this poster will be added to the list of initial sparks for one of my novels.

A nun’s day at a Scout camp? How could this not be the basis for a novel?