Bryan Islip's Blog, page 29

November 15, 2012

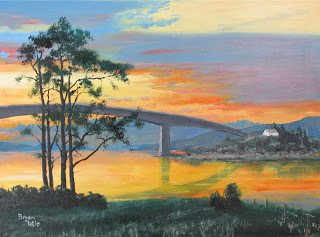

Speed bonnie bridge

I find the best antidote to worry is to create something. Could be my latest chapter, or an edit of my novel in progress or a painting such as this latest oil on 60 x 46cm canvas that I will call Sunset over the sea to Skye, or it could even be the 'associated' verse that I always compose during or after a painting is done and dusted. Anything to prevent my mind from circling round and around the dreaded cancer, or more accurately the 'non-Hogkinson's lyphoma' from which Delia is suffering.

I did the original sketches and took photos back in the early summer, having driven across on to the island and turned left.

The sunset is a different sketch as are the scottish pines in the forground. For me composition is more than half the battle/ I have little desire to paint exactly what is there. The pines for instance are the clump you will see on the right hand side of the roadway travelling from Ullapool to Inverness - just after you pass the Braemore junction. Bonnie Prince Charlie, speeding in his bonnie boat like a bird on the wing, would have more likely seen these than the deciduous / anonymous trees that are actually there today.

Skye bridge is relatively of recent construction and began its life as a toll bridge. However it rapidly became a free passage under the weight of thousands of local protests. Not everything has to be for money.

A couple of weeks ago I blogged about my previous oil on canvas, the one called 'Starlings'. Looking at it again I see my photo of it was pretty awful so I have shot another one. Here it is ...

Published on November 15, 2012 04:44

November 14, 2012

Less power to the people

A gentleman asked me to support the public protest against a wind turbine to be sited at Mellon Udrigle - one of the more seascapes in Scotland, (which could mean in the world). This is my response. I'd like to share it with you ...

"Thank you for the opportunity to register my

protest against the Mellon Udrigle wind turbine. I am happy to do so but

unfortunately my cut and paste effort to get on site failed for some reason.

I'll try again later on.

Ah, the vexed question of those damn great

three-armed monoliths fast beeeding all over these islands - especially in the

remoter, less inhabited, more unspoiled regions. (Of course these are the places

where they can and do wreck the environment the most and at the same time attract the least

residential opposition!)

At first I confess to having had mixed feelings on

the subject of wind farms. Anything but nuclear, thought I, (and still do). Then

I looked out of my window on Loch Ewe and considered the trillions of tonnes of

sea water sloshing to and fro out there twice daily. The power within. And I

looked up at the daytime sky and thought of the trillions of kilowatt

energy beaming down on us. The power on high.

Most of all I thought of humankind's latterday need

for power / energy. I thought of the amount of it we think we 'need' per each

individual on these islands, on this planet Earth; four billions of us when I

was born, rising seven billions a scant seventy eight years later. And in

seventy eight more of these short years?

Flying south to visit our family I looked down on a

trillion street lights and wondered what they were actually for. As a boy I

remember lightless London, cars only with pinprick sidelights. I do not recall

any great hardship or any great inconvenience. I do recall the general air of calm content. Why, I wondered, in an age of

anyone can see anywhere, anyone can talk to anyone through our marvellous

digitalia, why do we need all this travel and the usage of power to do

so? Heathrow is like an ant hill frenzied into mad, hither and thither action by

some snuffling marauder. There's no marauder so what for all the rush and tear,

exactly? Ditto our roadways, in spades.

But if we cannot control ourselves and are happy to

approach the abyss on a wave of well-lit euphoria why not site all the wind

turbines above the cities? That's where the people are who seem to need the

power for their central heating - at whatever cost and to avoid the necessity of donning an extra jumper, I guess - and for all the domestic gadgetry, street

lights, said travel etc etc.

Meantime Hamish, I applaud your efforts. I see

you charging the windmills like Don Quixote, cheered on by me as Sancho Panza.

But you know, if there are enough Don Quixotes ..."

Can anyone please tell me by what logic my response falls down? Please?

"Thank you for the opportunity to register my

protest against the Mellon Udrigle wind turbine. I am happy to do so but

unfortunately my cut and paste effort to get on site failed for some reason.

I'll try again later on.

Ah, the vexed question of those damn great

three-armed monoliths fast beeeding all over these islands - especially in the

remoter, less inhabited, more unspoiled regions. (Of course these are the places

where they can and do wreck the environment the most and at the same time attract the least

residential opposition!)

At first I confess to having had mixed feelings on

the subject of wind farms. Anything but nuclear, thought I, (and still do). Then

I looked out of my window on Loch Ewe and considered the trillions of tonnes of

sea water sloshing to and fro out there twice daily. The power within. And I

looked up at the daytime sky and thought of the trillions of kilowatt

energy beaming down on us. The power on high.

Most of all I thought of humankind's latterday need

for power / energy. I thought of the amount of it we think we 'need' per each

individual on these islands, on this planet Earth; four billions of us when I

was born, rising seven billions a scant seventy eight years later. And in

seventy eight more of these short years?

Flying south to visit our family I looked down on a

trillion street lights and wondered what they were actually for. As a boy I

remember lightless London, cars only with pinprick sidelights. I do not recall

any great hardship or any great inconvenience. I do recall the general air of calm content. Why, I wondered, in an age of

anyone can see anywhere, anyone can talk to anyone through our marvellous

digitalia, why do we need all this travel and the usage of power to do

so? Heathrow is like an ant hill frenzied into mad, hither and thither action by

some snuffling marauder. There's no marauder so what for all the rush and tear,

exactly? Ditto our roadways, in spades.

But if we cannot control ourselves and are happy to

approach the abyss on a wave of well-lit euphoria why not site all the wind

turbines above the cities? That's where the people are who seem to need the

power for their central heating - at whatever cost and to avoid the necessity of donning an extra jumper, I guess - and for all the domestic gadgetry, street

lights, said travel etc etc.

Meantime Hamish, I applaud your efforts. I see

you charging the windmills like Don Quixote, cheered on by me as Sancho Panza.

But you know, if there are enough Don Quixotes ..."

Can anyone please tell me by what logic my response falls down? Please?

Published on November 14, 2012 02:57

November 13, 2012

The food of love?

Apparently this is the sixtieth anniversay of the UK's pop music chart.

This morning the BBC's Breakfast reporter was asking a few primary school boys and girls what they thought about that first (1952) Top of the Pops, Al Martino's Here In My Heart. Those of my own pre-Talking About My Generation generation will know Here In My Heart for the soft, sentimental and beautifully sung love song that it is. 'Wierd', however, was the general kiddiewink consensus amidst all the embarrassed giggling, the furtive who is this guy glances one to another.

The reporter then proceeded to interview a few wrinklies on the tea dance floor of the Tower Ballroom, Blackpool. He played then the latest top of the pops, a harshly cacaphonic number by I forget which singer, probably aimed at today's drug fuelled Clubbers. General, genuine bewilderment.

If music be indeed Shakespeare's food of love, where ever has it gone? And what is to replace it for those little children soon to be all grown up and presumably looking as much as did we for that self same love?

Can we have changed all that much in the blink of time's eye which we call sixy years?

Or could it merely be our media induced perceptions that have changed, leaving us just the same 'inside'? I reckon so. I hope so.

This morning the BBC's Breakfast reporter was asking a few primary school boys and girls what they thought about that first (1952) Top of the Pops, Al Martino's Here In My Heart. Those of my own pre-Talking About My Generation generation will know Here In My Heart for the soft, sentimental and beautifully sung love song that it is. 'Wierd', however, was the general kiddiewink consensus amidst all the embarrassed giggling, the furtive who is this guy glances one to another.

The reporter then proceeded to interview a few wrinklies on the tea dance floor of the Tower Ballroom, Blackpool. He played then the latest top of the pops, a harshly cacaphonic number by I forget which singer, probably aimed at today's drug fuelled Clubbers. General, genuine bewilderment.

If music be indeed Shakespeare's food of love, where ever has it gone? And what is to replace it for those little children soon to be all grown up and presumably looking as much as did we for that self same love?

Can we have changed all that much in the blink of time's eye which we call sixy years?

Or could it merely be our media induced perceptions that have changed, leaving us just the same 'inside'? I reckon so. I hope so.

Published on November 13, 2012 00:39

November 8, 2012

Painting rainbows

This is my latest completed painting. Oil on canvas 70 x 50cm.

You'll get the analogy if you've seen my blog of a week or three ago - the one about popping around the corner for a litre of milk only to be confronted by a ten foot tall grizzly bear.

Painting rainbows is difficult. Finding your way over them - that's easy, one day, for each and every one of us. And once there, there's no more hurt ... grizzlie bears or otherwise.

Published on November 08, 2012 02:53

November 2, 2012

Talking of War and Peace

Just now I'm re-reading Mailer's The Naked and the Dead, the novel I first read exactly 50 years ago. This has been called the finest to come out of WW2 and maybe the finest since Tolstoi. Mailer's is quite brilliant but in my opinion suffers from adjectival excess and an odd sense of understanding without compassion. I would probably vote for Im Westen nichts Neues - All Quiet on the Western Front - the novel by German veteran of World War I, Erich Maria Remarque; or my oft-quoted favourite, Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls - miles in front for use of words and language; for simply taking you there, like it or not.

Of course these reflections are inspired by the date: 11/11/1911 draws near. I need to remember to buy a poppy. I looked up a compendium of short poems I wrote in I think 1996 and addressed to some of the many poets killed in 'The Great War'. Surely an oxymoron - is there really any thing great in a war, especially that one? Anyway ...

IN WOUNDED FIELDS

Prologue

We

wander down the subterranean shaft

In

which the museum at Albert, Picardy,

Conceals

from this town’s normal life

The

bloody, muddy face

Of

World War One,

The

stinking trenches

And

all the wounded fields.

And

you can hear the dying;.

Taste

the death down here;

In

our strange silence I do not want to stay

Where

no words come

But

find I cannot quickly take myself away....

In

the souvenir shop on the way out

Of

the brick-arch tunnel, cold stone floor,

Before

reaching the fresh air of the town

We

look in silence still

Through

sickly memorabilia

And

at the history books:

And

from a nice French lady buy one

Called; “Violets from Oversea;”

By

Toni and Valmai Holt

(Illustrations

Charlotte Zeepvat)

That

tells how from chaos flowered poesy,

Avoids

the use of the word ‘hero,’

Of

poets speaks without hypocricy.

And

outside in the thin October rain

As

I look high up to the golden virgin,

Child

in her outstretched hands, against grey sky,

That

surmounts the Town Hall

(Known

to the soldiers as The Angel of Albert,)

And

later, reading of those soldier poets -

I

know I have to say some thing.

To

some of them, anyway.

Bryan

Islip

October

96

Note: Words italicised throughout In Wounded Fields are those of the subject poet.

To Charles Hamilton Sorley;

19 May 1895 - 28 April 1915

Hello

pale youth, lip touched with thin moustache,

Captain,

D Company, Suffolk

Regiment,

Cross-Wiltshire

running old Marlburian:

At

you fast sped the unkind spinning lead

At

Loos to drill your helmet, still so new.

How

all too true your words of how...“Earth...

Shall rejoice and blossom too

When the bullet reaches you.”

Wherever

did you stow your socialism,

Your

bitter sense of anti-Kiplingism?

When

you packed up your old kit-bag, and where

Your

liking for Goethe & Rilke, Ibsen?

(Not

for Hardy, your love of him had lapsed)

Your

marchers...”All the hills and vales

along...

The singers are the chaps

Who are going to die perhaps.”

But

listen, you could have been one of those

Pieces of living pulp you so dreaded having

To

carry back across that no-man’s waste:

Or

one of those with you at Ypres who

Had

breathed deep of the gently shifting breeze,

Blinked,

blinded by its gift of British gas,

Coughed

out their sightless time in yellow pus.

You

could have been...have been the dramatist,

The

best, John Masefield, Poet Laureate said,

Since

that Stratfordian, if you had lived.

“I am giving my body,” you wrote, (I

think

He’d

like your shocking words,) “To fight

against

The most enterprising

nation in the world”

But

Charles how straight you stood, your flag unfurled!

Sighing,

you folded; sank spent-muscled down

Into

that slime and no-one said soft things:

No

bands of angels took thee to thy rest.

They

never found you, Captain Sorley, did they?

Though

lost you not for minds cannot decay,

And

you would know, sweet twenty, soldier prince,

It

matters not in what dark earth you lay...

...And

after in your muddy kitbag there

They

found your cry against what Brooke had said:

Your

cry; “Say only this; that they are dead.”

****

To:

Leslie Coulson July 1889 -

October 1916

“Who spake the Law that men

should die in meadows?”

You

ask and I reply, ‘Man spake that Law,’

(Though

in regards to other than himself;)

And

in pursuance since the dawn of human

Kind

has killed and died in meadows, towns

Upon

the seas and hills, now in the air

And

after questioned why, and was it fair.

Why? No-one knows - and fair? Who is to care?

“Who spake the word that

blood should splash in lanes?”

You

ask and I reply, ‘You spake that word,

You,

Sergeant, for by just being there -

Proud

member of the London Regiment

Retreating

last from lost Gallipoli

-

With all those men, some khaki some in grey

Who’ll

fight until one colour wins the day

‘Till

thick in lanes the dead, the dying lay.

“Who gave it forth that

gardens should be boneyards?”

You

ask and I say it was ever thus,

Beneath

the beauty always lie the bones

That

nourish it, upon which it must feed

As

feeds nobility in war upon the lost,

The

crying of the dead, the awful dying:

You

who vainly fought, near Albert lying,

Your

bones now ‘neath the nodding flowers, sighing.

“Who spread the hills with

flesh and blood and brains?”

You

ask and know the answer: it is you

Who

trained your smoking gun upon the foe,

Who

covered hills with screaming shot and shell

To

deaden all that runs or flies or grows.

For

more than this ask your creator God,

Your

fingers stiffly clawed into the sod,

‘Till

agony is spent with all your blood.

‘All the blood that war has

ever strewn is

But a passing stain,’ you wrote... before the

start...

*****

To Francis Ledwidge August 1887 - July 1917

Did

you still, “Hear roads calling and the

hills

And the rivers, wondering

where I am,”

At

Hellfire Corner, sitting drinking tea

As

arced unseen that deadly mortar bomb

Which

was to end an Irish poet’s dream?

A

long way sure, from Owen, Brooke, and those

Smart

young men in smarter khaki clothes

Who

never mended any metalled road

Yet

were your brothers of the silken verse

And

knew as well as you the smell of death.

I

wonder what became of all your clan

(Nine

children to evicted farming man:)

Perhaps

your father was a dreamer too,

Dreaming, “Songs of the fields,” just as you,

His

Celtic longing more than mind can bear.

But

what genetic streak of ancient Gael

Gave

will to write and sensitivity

To

know; “And greater than a poet’s fame

A little grave that has no

name;” tell me,

You

school-less twelve year old adrift, tell me,

Lance

Corporal Francis Ledwidge, fighting man,

Sometime

Slane Corps of Irish Nationalists

Now

Inniskilling Fusiliers, enrolled

To

kill the foe of She who’s not your friend

And

fight for her through hell’s Gallipoli.

And

how, I wondered, could a poet write

In

winter trenches on the brutal Somme

Of

lilting “Fairy Music” (“Ceol Sidhe”)?

Was

still the barred cuckoo so real to you,

In

Crocknahara meadows by the Boyne?

Always

you yearned for mother, Ireland,

“The fields that call

across the world to me,”

And

now near where the spires of Ypers stand

You

dream your dreams, denied reality,

Beneath

your wild flowers ‘till the end.

****

To Roland Aubrey Leighton:

March 1895 - December 1915

We

searched the lanes, found you in Louvencourt’s

Small

cemetry amidst a company

Of

stones standing straight-rowed to attention,

Smart

white in a slow rain, near where you died;

‘Lieutenant

R A Leighton 7th Worcesters,’

Says

your monument; said that telegram.

“I walk alone although the

way is long,”

You

said, in private lines in your black book,

“And with gaunt briars and

nettles overgrown;”

What

pain you meant by this we’ll never know.

Just

such a light so bright as yours aligns

The

many-splendoured ones on which it shines.

She

capitalised your ‘Him’ as godheads do

Whenever

afterwards she wrote of you.

Yes,

“Life is love and love is you, dear, you”

You

wrote, prize scholar bursting sweating out

Of

your illicit wet night dreams of she,

Who’d

written to herself ;’Impressive, he,

Of

powerful frame, pale face and stiff thick hair.’

Would

you we know had she not loved you so?

Dee likes to know you in those violets,

Pressed

brown and withered, desiccated now,

You

sent to Vee from shattered 'Plug

Street' Wood,

Picked

from red sticky ground around the head,

The

horrid face and splintered skull that she

Must

never see?... She, Vera of the V A D?

Who,

from your sceptic pact with her enticed

Your

secret taking of Rome’s

hand of Christ?

And

I, not knowing of you very much,

Looked

in that brass bound book at Louvencourt

Read

this year’s batch of private messages

To

you, young friend, mostly from those unborn

When

that one, shiv’ring in his field grey,

Unsurprised

to see you that cold night, glad

Of

the Christmas gift, squeezed the steel trigger,

Exploding

pain into your youthful frame...

From

far and wide they’d come to speak their grief,

So

many words to you who wrote so few.

Why

stood you there, why dare the guns, Roland?

‘Hinc illae lacrimae;’* your code...

I

still don’t understand....

* Hence those

tears’ .... (Terence)

****

To: John McRae: November

1872 - January 1918

Youth

steals away from all who live, McRae,

Though

weary not the sons the Highlands yields,

Canadian

now (except on Empire Day,)

You’re

‘uncle’ to the boys in Flanders’ fields.

You

wrote; “In Flanders

Fields the poppies blow;”

And

midst the dogs of war you heard the lark,

Went

on; “We shall not sleep, though poppies

grow,”

(If

generations new allow the dark.)

They

say you wrote it by first morning light

One

bloody Ypres day in May, ‘15,

As

German chlorine robbed men of their sight,

Oh,

few men see what you, Doctor, have seen -

Seen

six out of each ten Canadians

Sans

life sans love sans laughter; sans all sans...

Did

you, Lieutenant Colonel John McRae,

Veteran

of Boer war, Loos and Passchendaele,

For

them your prayers say each dying day?

Your

healing hands artillery did lay?

But

did, for you, sometimes the tumult fade,

Did

agonies relent as words unfold?

Recalled

within your notebook was peace made;

“A little maiden fair /

With locks of gold.”?

And

left you more than she a-weeping and,

Before

the war fell you for Lady R...?

Why

never did you let a wedding band

Be-threat

the edge of sword Excalibre?

I

hope you filled life’s chalice to the brim -

And

that you knew not Haig, but pitied him.

Then

April, seventeen; with crimson end

Was

Canada,

enobled nation made -

On

Vimy Ridge. And afterwards you penned;

“The Anxious Dead;” and you were not afraid.

Oh

Jack McRae, few men were loved as you:

Men

clung to you as shadows cling to men;

Still

wear your poppies to hold glorious who

Found

glory in a dark beyond their ken.

The

horse you cherished led your black cortege,

Turned

boots in stirrup irons to say you’re dead,

Men's

tears at Wimereux were not of rage

But

love for one ashamed to die in bed...

And

in the going down of every sun

Some

shall recall your words each one by one.

Called MacUrtsi was each

poet to your clan,

Goodbye Doctor, MacUrtsi, McRae, Man.

****

IN

WOUNDED FIELDS

Epilogue

And

so I had my discourse with these poets

And

with the others from that book

Who’d

gone to war with heads held high but knew

Scant

glory in the mud, and died,

Yet

found their songs and verse

In

such a torrent rushed

As

might have changed the world

I

thought of how wild flowers

In

brightest beauty blaze

Where

ordure thickest lies -

It's

stink by glory overpowered.

This

place of peace holds very little trace

Of

what had come to pass those years before.

But

rust away as may the swords

I

shall remember poet’s words

And

we shall remember them

Long

after all the blood and all the bedlam,

Long

after time has healed the wounded fields.

Bryan

Islip

October

96

Of course these reflections are inspired by the date: 11/11/1911 draws near. I need to remember to buy a poppy. I looked up a compendium of short poems I wrote in I think 1996 and addressed to some of the many poets killed in 'The Great War'. Surely an oxymoron - is there really any thing great in a war, especially that one? Anyway ...

IN WOUNDED FIELDS

Prologue

We

wander down the subterranean shaft

In

which the museum at Albert, Picardy,

Conceals

from this town’s normal life

The

bloody, muddy face

Of

World War One,

The

stinking trenches

And

all the wounded fields.

And

you can hear the dying;.

Taste

the death down here;

In

our strange silence I do not want to stay

Where

no words come

But

find I cannot quickly take myself away....

In

the souvenir shop on the way out

Of

the brick-arch tunnel, cold stone floor,

Before

reaching the fresh air of the town

We

look in silence still

Through

sickly memorabilia

And

at the history books:

And

from a nice French lady buy one

Called; “Violets from Oversea;”

By

Toni and Valmai Holt

(Illustrations

Charlotte Zeepvat)

That

tells how from chaos flowered poesy,

Avoids

the use of the word ‘hero,’

Of

poets speaks without hypocricy.

And

outside in the thin October rain

As

I look high up to the golden virgin,

Child

in her outstretched hands, against grey sky,

That

surmounts the Town Hall

(Known

to the soldiers as The Angel of Albert,)

And

later, reading of those soldier poets -

I

know I have to say some thing.

To

some of them, anyway.

Bryan

Islip

October

96

Note: Words italicised throughout In Wounded Fields are those of the subject poet.

To Charles Hamilton Sorley;

19 May 1895 - 28 April 1915

Hello

pale youth, lip touched with thin moustache,

Captain,

D Company, Suffolk

Regiment,

Cross-Wiltshire

running old Marlburian:

At

you fast sped the unkind spinning lead

At

Loos to drill your helmet, still so new.

How

all too true your words of how...“Earth...

Shall rejoice and blossom too

When the bullet reaches you.”

Wherever

did you stow your socialism,

Your

bitter sense of anti-Kiplingism?

When

you packed up your old kit-bag, and where

Your

liking for Goethe & Rilke, Ibsen?

(Not

for Hardy, your love of him had lapsed)

Your

marchers...”All the hills and vales

along...

The singers are the chaps

Who are going to die perhaps.”

But

listen, you could have been one of those

Pieces of living pulp you so dreaded having

To

carry back across that no-man’s waste:

Or

one of those with you at Ypres who

Had

breathed deep of the gently shifting breeze,

Blinked,

blinded by its gift of British gas,

Coughed

out their sightless time in yellow pus.

You

could have been...have been the dramatist,

The

best, John Masefield, Poet Laureate said,

Since

that Stratfordian, if you had lived.

“I am giving my body,” you wrote, (I

think

He’d

like your shocking words,) “To fight

against

The most enterprising

nation in the world”

But

Charles how straight you stood, your flag unfurled!

Sighing,

you folded; sank spent-muscled down

Into

that slime and no-one said soft things:

No

bands of angels took thee to thy rest.

They

never found you, Captain Sorley, did they?

Though

lost you not for minds cannot decay,

And

you would know, sweet twenty, soldier prince,

It

matters not in what dark earth you lay...

...And

after in your muddy kitbag there

They

found your cry against what Brooke had said:

Your

cry; “Say only this; that they are dead.”

****

To:

Leslie Coulson July 1889 -

October 1916

“Who spake the Law that men

should die in meadows?”

You

ask and I reply, ‘Man spake that Law,’

(Though

in regards to other than himself;)

And

in pursuance since the dawn of human

Kind

has killed and died in meadows, towns

Upon

the seas and hills, now in the air

And

after questioned why, and was it fair.

Why? No-one knows - and fair? Who is to care?

“Who spake the word that

blood should splash in lanes?”

You

ask and I reply, ‘You spake that word,

You,

Sergeant, for by just being there -

Proud

member of the London Regiment

Retreating

last from lost Gallipoli

-

With all those men, some khaki some in grey

Who’ll

fight until one colour wins the day

‘Till

thick in lanes the dead, the dying lay.

“Who gave it forth that

gardens should be boneyards?”

You

ask and I say it was ever thus,

Beneath

the beauty always lie the bones

That

nourish it, upon which it must feed

As

feeds nobility in war upon the lost,

The

crying of the dead, the awful dying:

You

who vainly fought, near Albert lying,

Your

bones now ‘neath the nodding flowers, sighing.

“Who spread the hills with

flesh and blood and brains?”

You

ask and know the answer: it is you

Who

trained your smoking gun upon the foe,

Who

covered hills with screaming shot and shell

To

deaden all that runs or flies or grows.

For

more than this ask your creator God,

Your

fingers stiffly clawed into the sod,

‘Till

agony is spent with all your blood.

‘All the blood that war has

ever strewn is

But a passing stain,’ you wrote... before the

start...

*****

To Francis Ledwidge August 1887 - July 1917

Did

you still, “Hear roads calling and the

hills

And the rivers, wondering

where I am,”

At

Hellfire Corner, sitting drinking tea

As

arced unseen that deadly mortar bomb

Which

was to end an Irish poet’s dream?

A

long way sure, from Owen, Brooke, and those

Smart

young men in smarter khaki clothes

Who

never mended any metalled road

Yet

were your brothers of the silken verse

And

knew as well as you the smell of death.

I

wonder what became of all your clan

(Nine

children to evicted farming man:)

Perhaps

your father was a dreamer too,

Dreaming, “Songs of the fields,” just as you,

His

Celtic longing more than mind can bear.

But

what genetic streak of ancient Gael

Gave

will to write and sensitivity

To

know; “And greater than a poet’s fame

A little grave that has no

name;” tell me,

You

school-less twelve year old adrift, tell me,

Lance

Corporal Francis Ledwidge, fighting man,

Sometime

Slane Corps of Irish Nationalists

Now

Inniskilling Fusiliers, enrolled

To

kill the foe of She who’s not your friend

And

fight for her through hell’s Gallipoli.

And

how, I wondered, could a poet write

In

winter trenches on the brutal Somme

Of

lilting “Fairy Music” (“Ceol Sidhe”)?

Was

still the barred cuckoo so real to you,

In

Crocknahara meadows by the Boyne?

Always

you yearned for mother, Ireland,

“The fields that call

across the world to me,”

And

now near where the spires of Ypers stand

You

dream your dreams, denied reality,

Beneath

your wild flowers ‘till the end.

****

To Roland Aubrey Leighton:

March 1895 - December 1915

We

searched the lanes, found you in Louvencourt’s

Small

cemetry amidst a company

Of

stones standing straight-rowed to attention,

Smart

white in a slow rain, near where you died;

‘Lieutenant

R A Leighton 7th Worcesters,’

Says

your monument; said that telegram.

“I walk alone although the

way is long,”

You

said, in private lines in your black book,

“And with gaunt briars and

nettles overgrown;”

What

pain you meant by this we’ll never know.

Just

such a light so bright as yours aligns

The

many-splendoured ones on which it shines.

She

capitalised your ‘Him’ as godheads do

Whenever

afterwards she wrote of you.

Yes,

“Life is love and love is you, dear, you”

You

wrote, prize scholar bursting sweating out

Of

your illicit wet night dreams of she,

Who’d

written to herself ;’Impressive, he,

Of

powerful frame, pale face and stiff thick hair.’

Would

you we know had she not loved you so?

Dee likes to know you in those violets,

Pressed

brown and withered, desiccated now,

You

sent to Vee from shattered 'Plug

Street' Wood,

Picked

from red sticky ground around the head,

The

horrid face and splintered skull that she

Must

never see?... She, Vera of the V A D?

Who,

from your sceptic pact with her enticed

Your

secret taking of Rome’s

hand of Christ?

And

I, not knowing of you very much,

Looked

in that brass bound book at Louvencourt

Read

this year’s batch of private messages

To

you, young friend, mostly from those unborn

When

that one, shiv’ring in his field grey,

Unsurprised

to see you that cold night, glad

Of

the Christmas gift, squeezed the steel trigger,

Exploding

pain into your youthful frame...

From

far and wide they’d come to speak their grief,

So

many words to you who wrote so few.

Why

stood you there, why dare the guns, Roland?

‘Hinc illae lacrimae;’* your code...

I

still don’t understand....

* Hence those

tears’ .... (Terence)

****

To: John McRae: November

1872 - January 1918

Youth

steals away from all who live, McRae,

Though

weary not the sons the Highlands yields,

Canadian

now (except on Empire Day,)

You’re

‘uncle’ to the boys in Flanders’ fields.

You

wrote; “In Flanders

Fields the poppies blow;”

And

midst the dogs of war you heard the lark,

Went

on; “We shall not sleep, though poppies

grow,”

(If

generations new allow the dark.)

They

say you wrote it by first morning light

One

bloody Ypres day in May, ‘15,

As

German chlorine robbed men of their sight,

Oh,

few men see what you, Doctor, have seen -

Seen

six out of each ten Canadians

Sans

life sans love sans laughter; sans all sans...

Did

you, Lieutenant Colonel John McRae,

Veteran

of Boer war, Loos and Passchendaele,

For

them your prayers say each dying day?

Your

healing hands artillery did lay?

But

did, for you, sometimes the tumult fade,

Did

agonies relent as words unfold?

Recalled

within your notebook was peace made;

“A little maiden fair /

With locks of gold.”?

And

left you more than she a-weeping and,

Before

the war fell you for Lady R...?

Why

never did you let a wedding band

Be-threat

the edge of sword Excalibre?

I

hope you filled life’s chalice to the brim -

And

that you knew not Haig, but pitied him.

Then

April, seventeen; with crimson end

Was

Canada,

enobled nation made -

On

Vimy Ridge. And afterwards you penned;

“The Anxious Dead;” and you were not afraid.

Oh

Jack McRae, few men were loved as you:

Men

clung to you as shadows cling to men;

Still

wear your poppies to hold glorious who

Found

glory in a dark beyond their ken.

The

horse you cherished led your black cortege,

Turned

boots in stirrup irons to say you’re dead,

Men's

tears at Wimereux were not of rage

But

love for one ashamed to die in bed...

And

in the going down of every sun

Some

shall recall your words each one by one.

Called MacUrtsi was each

poet to your clan,

Goodbye Doctor, MacUrtsi, McRae, Man.

****

IN

WOUNDED FIELDS

Epilogue

And

so I had my discourse with these poets

And

with the others from that book

Who’d

gone to war with heads held high but knew

Scant

glory in the mud, and died,

Yet

found their songs and verse

In

such a torrent rushed

As

might have changed the world

I

thought of how wild flowers

In

brightest beauty blaze

Where

ordure thickest lies -

It's

stink by glory overpowered.

This

place of peace holds very little trace

Of

what had come to pass those years before.

But

rust away as may the swords

I

shall remember poet’s words

And

we shall remember them

Long

after all the blood and all the bedlam,

Long

after time has healed the wounded fields.

Bryan

Islip

October

96

Published on November 02, 2012 03:21

November 1, 2012

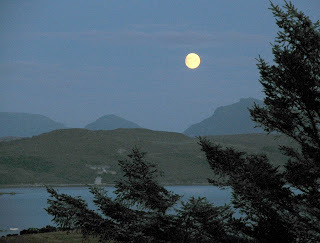

The pale moon is rising

This is a photograph I took one night not so long ago, reminding me of the first line of a song I've sung - to often less than enraptured audiences - in many an alcoholic gathering: 'The pale moon is rising above the blue mountains' (the sun is declining beneazth the green sea.) Almost certainly those words are slightly or entirely wrong. Dee says I know a couple of wrong lines in every song ever written. Small exaggeration no doubt, but the lady is inclined to exaggerate and we all have faults do we not? Even she.

I took the photo from outside our home in Aultbea, therefore the water is Loch Ewe and the mountain (or 'hill' as, locally, we call all Scottish mountains) is Beinn Airidh Charr. I often think when looking at this one of our friend M's account of her ascent of it, years ago, probably before Mr Armstrong set first foot on that golden orb up there. She was and we were so much younger and fitter than now. Sigh! But hey, looking back is a mistake and besides, I get as much pleasure from just seeing the hill that was there long before Mankind first set foot on planet earth than were I able to climb it this very day. I wonder if I could? ... well, I know I could try ...

Could Beinn Airidh Charr be the "Beinn Torobach" in my novel in progress? Could be, but then so could Baosbeinn, An Teallach, Beinn Groblach of any one of a half hundred others here on the bewitchingly beautiful West coast of the Highlands of Scotland. The first eighteen chapters are now on line if you're interested, and nineteen of the whole, maybe twenty four, is coming along. Even the Second Coming along, perhaps?

Published on November 01, 2012 10:28

October 30, 2012

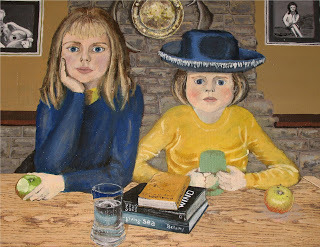

Ain't it funny

This is an oil painting c 30 x 25 cm. I executed it around 1970, the year we moved south as demanded by my career progression, from Lancashire to Hampshire. However it is possible my two lovely girls, Kairen Jane (left) and Julie Elaine may have been younger than the 14/15 and 11/12 indicated by that date.

It is for some reason unfinished. Strange, that. Any painting I didn't like and didn't finish just never survived and this one has, for it hangs today on my office wall at home.

The background stonework surrounds a fireplace I designed and we had installed in our new home at Lee-on-the-Solent. The pictures on the wall are probably of my first wife Joan. And the books? Dixon's 'Gairloch' (so after our first ever holiday in Scotland), Bellamy's 'The Life Giving Sea' and 'Gone With The Wind'. I like the water glass and I think my daughter's are wondering when Dad would let them get up and get on!

42 long and crowded years gone in a flash; a reminder of our brief stay on earth. As Willie Nelson wrote and sang, ain't it funny how time drifts away.

Published on October 30, 2012 02:38

October 26, 2012

Painting starlings

I've begun painting again with oils on canvas. I'd almost forgotten how great is the feel of the stuff - well mixed linseed oil, genuine American turpentine, pigments squeezed straight from the Winsor and Newton tube.

Subject puzzling you? It was prompted by a passage in a recent chapter of my on-line novel in progress, The Book. Teenager Jamie is out fishing a sea loch with Ben, his father, and old boatowner Donny MacLean. Young Jamie is rowing back in ...

Hundred metres left to go. Jamie said, ‘Mister

MacLean, you’ve seen the starlings, haven’t you? On Springwatch or something?

We don’t have TV here but I’ve seen them. Thousands and thousands all flying

packed close together, wheeling about in the sky making kinds of abstract

patterns? They turn like they were all part of one single flying creature but

they are not, they are all individuals so there must always be the one who has

to make decisions, decide to turn first. All the others follow of their own

free will, almost instantaneous. If they didn’t do it together they would

collide with each other. But you can see there’s always one that breaks away

and he or she takes others with him - or her - to make their own patterns.’

‘Starlings?’ The old man shook his head, puzzled.

‘The laddie talks in riddles, Ben.’

Ben grinned. ‘Sometimes I think the riddles make

more sense than anything. As he says, somebody has to make the first turn.

Things do change, Donny. Here or anywhere.’

‘Oh yes. But forget about the starlings before we

hit the jetty,’ Donny said, not unkindly. ‘Stop rowing now and ship your oar.

Ready the painter.’

Published on October 26, 2012 09:12

October 23, 2012

A walk in the sunshine

I've often talked of our customary mid-day walk 'to the NATO'. Well, here are a few shots I took during yesterday's ramble up the lochside.But please don't let me give you the impression that such weather is in any way normal, especially at the time of these equinoctal tides. (Half way up in these shots)

Pic 1 shows Kirkhill House, our rented home in Aultbea. The B&B Dee has been running so successfully has now of course put the shutters up, perhaps temporarily depending on progress with Dee's newly diagnosed cancer.

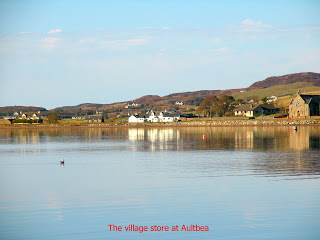

The second picture shows the village store (white buildings) and kirk (church - stone buildingon the right)

Dee on one of her usual rocky perches. Here is where we sit eating our sandwiches etc, close by the crumbling remains of a wartime gun emplacement. The land across the water is

Isle Ewe - about a mile out into Loch Ewe itself.

And this is a reminder of the quote (probazbly mis-qote) "All the world is beautiful and only Man is vile."

Some bastard - probably military at the end of WW2 when they'd had what they wanted from this area - just left their xxxxxxx earth mover where it broke down and xxxxxxxx off back south. Thank you for nothing, whover you were.

Published on October 23, 2012 02:07

October 18, 2012

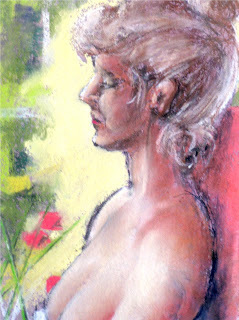

Delia sunbathing

I've recently. been blogging a bit about my wife Delia. This is a ten minute 'impressionist' pastel sketch of her. She is asleep whilst sunbathing in our garden some years ago.

Before we moved to the far north of Scotland, in those innocent days before we learned about skin cancer, Dee was indeed a world class sun worshipper. Lying in the blazing sun smoking cigarette after cigarette was what folk did.

Perhaps oddly enough her current, recently diagnosed bone cancer has nothing whatever to do with the sun - to the best of current klnowledge at least.

The more we learn about cancer and the ways in which it can attack the human physiology the more astonished we are at the enormous complexity of the whole subject. And the more we understand the imprecision of cancer in terms of origination, diagnostics, progrnostics and treatment. No doubt one day all will be revealed. Right now, four long weeks after the firsat hospitalisation we're still struggling to come to terms with it and all its issues.

One thing I will say. If you happen to have any pennies, cents, drachmas, riyals or any other hard currency to spare, they would be extremely spent at Cancer Macmillan

Published on October 18, 2012 07:29