Viet Thanh Nguyen's Blog, page 2

March 11, 2011

On (Not) Being Vietnamese

From Viet Thanh Nguyen's website, vietnguyen.info

Tet passed recently, and Vietnamese holidays always make me think about what it means to be Vietnamese, or not Vietnamese. I’m less interested in the question itself, because there’s no good answer to the question, and more interested in what it implies. The question implies that there is such a thing as Vietnameseness, and that we can define it with a list of things: you’re Vietnamese if you can tell the difference between good pho and bad pho, you’re Vietnamese if you have a favorite brand of fish sauce, you’re Vietnamese if you get teary at the sound of a Khanh Ly song, you’re Vietnamese if you know who Modern Talking is, you’re Vietnamese if…the list can go on. The question of what it means to be Vietnamese is only interesting to me because of the reason why I, or we, or anyone, might ask that question.

I am always getting asked a variation of that question. I went to this Tet party last month, and chatted with a young Vietnamese scholar recently arrived from Viet Nam. We had been speaking for a minute or so, in English, when she said, “You’re not Vietnamese, are you?” This reminded me of the time I had dinner with a group of Vietnamese studies specialists and this young Vietnamese doctoral student, recently from Viet Nam, said to me after a minute of conversation (in English), “There’s not much about you that’s still Vietnamese, is there?” This reminded me of the many times I had been to Viet Nam where people would say (after a few words in Vietnamese from me), “Your Vietnamese is so good!” This means that they thought I was not Vietnamese, since no one would compliment a Vietnamese person on his Vietnamese. I thought, this is what it must be like to be a white person in Viet Nam who breaks out her or his Vietnamese. People treat you so nicely just for being able to say “Please take me to Cho Ben Thanh.”

Whenever this happened, which was at least once a week, it would always remind me of those days in San Jose when I was a kid, in the 1980s, when my parents forced me to attend Vietnamese Catholic Sunday school. I barely spoke any Vietnamese back then, and in that time, in that place, you could not be Vietnamese if you did not speak Vietnamese. It was in the Vietnamese Catholic church, and in Vietnamese language classes, that I first developed my distaste for authenticity. Perhaps it was the pressure of being outsiders, refugees, newcomers to an American life they felt to be strange and one that they had not truly chosen that drove the Vietnamese I knew to define being Vietnamese narrowly. Their Vietnamese identity and culture was like an asteroid from a foreign planet that had come crashing to the American earth, and they would do everything they could to preserve it. So they had their rituals and festivals and masses and schools, where the prescriptions for being Vietnamese were very clear. If you felt included in that world, it was home.

Home was a comforting place, where people always welcomed you, made sure you had enough to eat, knew how to say your name. Home was also the place where people knew you enough to put you in your place, dislike you, hate you, have enough of you, take out their frustrations and rage on you. My parents lived and worked in the Vietnamese world, and the people they were most afraid of were other Vietnamese people. This was the other side of authenticity, the fact that if you knew what it meant to be really Vietnamese, then you also knew where the soft spots and deep hurt were as well. No one knows how to cut you down like another Vietnamese person, who’ll do it with a smile. No surprise that in the 1980s in San Jose, the crime Vietnamese people spoke most often of was the home invasion, when Vietnamese youth invaded the homes of people who looked just like them. The youth knew what hour of the day to come, who to torture, where to find the gold and cash. Was it my imagination, or was this just a repetition of the war, these kids who did the same things the older generation did in Viet Nam. I remembered how, in the second grade, circa 1979, the Vietnamese kids of my San Jose school had already formed gangs and fought each other over territory in the schoolyard. The Vietnamese people had brought their home with them, and home was a civil war, imposed on us by white people who were happy to watch us fight each other. At least in Viet Nam, we fought white people too. Was it my imagination, or in America, did the Vietnamese go out of their way to make white people feel at home whenever they encountered them.

I was never so glad as I was on the day I finally left home. It would take me two decades before I could come back to San Jose without feeling that I was being suffocated by the closeness of those walls of home. Strange, I felt freer going to Viet Nam than I did to San Jose. Not that Viet Nam doesn’t have its own basket case of problems, but it’s not my basket case. I didn’t go to Viet Nam with any expectation that I would suddenly feel at home, 100% Vietnamese, ready to kiss the soil of the motherland. I expected to feel like a foreigner, and that was what I was. The only problem was that the Vietnamese, once they knew who I was, expected me to feel and behave like a native, except when it came to financial matters, when they expected me to behave like a foreigner.

But this was all a long time ago. Wasn’t it? Nowadays the Vietnamese are redefining authenticity, since anything a Vietnamese person does in Viet Nam must be authentically Vietnamese. The rich Vietnamese are so rich they’re doing whatever rich people are doing everywhere, finding new and creative and absurd ways to spend their money, like the $37 bowl of pho or a Lamborghini on the streets of Saigon, where you can’t drive faster than 30 miles per hour. Come to think of it, you can’t drive anywhere in Viet Nam faster than 30 miles per hour. So if this is alien and foreign behavior in Viet Nam, it’s still Vietnamese behavior. Meanwhile, in the USA, there’s a whole new generation of Vietnamese Americans. Some of them want to do culture shows and preserve Vietnamese culture. Some people need to know what their culture is and find it reassuring to rehearse the motions, or to treat culture as if it is something found in a museum, static and unchanging.

But do contemporary Americans feel the need to prove their American culture by periodically wearing powdered wigs and tricorn hats and owning slaves? We think we have moved beyond all of that as Americans and are perfectly happy to think that James Franco represents American culture to the world today. But I haven’t been to a Vietnamese culture show in ten years and I’m curious to see whether today’s American-born students are still doing fan dances and candle dances dressed in peasant clothes, which is what my generation did, most of whom had never had their bare feet in a rice paddy. When I was growing up in San Jose in the hard eighties, I had no idea what a rice paddy might really be like. My idea of Vietnamese culture was that we were a very smart and resourceful people who knew how to both work for cash under the table while collecting welfare and food stamps. I’d like to see a culture show about that.

Nowadays there are some in the new generation who don’t speak any Vietnamese, who don’t care what white people think, and who may not really care that much about being Vietnamese either. Sometimes I run across them in person or see them do their thing from a distance, like Tila Tequila. She doesn’t proclaim her Vietnamese identity, but she is Vietnamese (of a certain kind) in the way she behaves. I’ve seen many like her in Saigon and San Jose, eager to move on up and look good while they’re doing it. Mostly I assume there are many, many more diverse Vietnamese I will never meet because I wouldn’t have a reason to–they’re not doing anything “Vietnamese.” More power to them. They are Vietnamese and they’re not Vietnamese all at the same time. What they do is Vietnamese and not Vietnamese all at the same time. The ability not to be forced by someone’s question about your authenticity into making an either/or answer–yes, I am Vietnamese, or no, I am not Vietnamese–which is to give in to the whole weight of someone else’s expectations around being “Vietnamese.” So the next time someone asks me if I’m really Vietnamese, I’m going to say “yes and no,” and then I will wait for them to ask me another question.

_____

“On (Not) Being Vietnamese” was originally published on on March 11, 2011.

The post appeared first on Viet Thanh Nguyen.

January 11, 2011

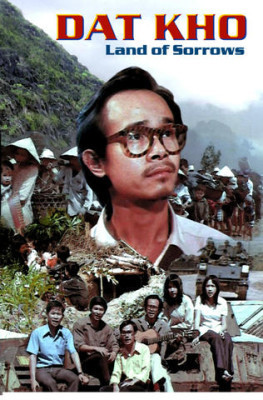

Trịnh Công Sơn, Movie Star: A Review of Đất Khổ (Land of Sorrows)

From Viet Thanh Nguyen's website, vietnguyen.info

I didn’t know Trinh Cong Son was in a movie until I saw Đất Khổ (Land of Sorrows). Filmed in 1971, the movie is set in Hue in the days before and during the Tet Offensive of 1968. I would really recommend this movie for anybody who is curious about life during wartime in southern Viet Nam. And for all those people who are going around saying they want to know what the Vietnamese point of view was, but keep looking only at Northern Vietnamese or Communist Vietnamese or Southern revolutionary points of view, here is the film you want to see. Clips are available on youtube (the whole movie is available in eleven parts–just type in “land of sorrows”), and the DVD can be bought on amazon.com, both with decent English subtitles. Now all those teachers and scholars and fanboys of the Viet Nam War have no excuse for not using or watching a movie that shows what life was like for the southern Vietnamese.

For those of you who don’t know, Trinh Cong Son was one of the most popular songwriters of the 1960s, and is often referred to by Americans as the “Bob Dylan of Viet Nam.” I don’t know about that, since such a moniker makes it seem that Trinh Cong Son is a knockoff or an imitator, but it gives you some sense of how popular he was. In the movie, he plays Quan, an antiwar songwriter and singer–as he was in real life–who comes home to Hue, where he encounters a family in turmoil. His eldest brother, Hai, is a captain in the ARVN who’s not happy about his antiwar activities, and who is furious that their younger sister, Hanh, is now protesting the war. Another sister, Thuy, is in love with Nghia, who is neutral in the war. A brother, Ha, has just been drafted.

Thus, the film sets up the classic dilemma of a family torn by conflicting loyalties during a period of revolution, or civil war, as some would argue. The drama unfolds both within the family and outside, as battles rage. There’s some remarkable usage of helicopters and armored personnel carriers, suggesting that the film had some government cooperation. We get to see how the war might have looked from the ARVN (southern Vietnamese army) point of view, which is rare in cinema. But most stunning of all is the incorporation of documentary footage of refugees fleeing from the battle of Hue, showing their fear and wounds (and including images of dead civilians and children on the road out of Hue). Quan’s family is caught up in the terror and are forced to flee…and I won’t tell you what else happens.

Throughout the course of the movie, Quan gets the chance to break out his guitar and sing his antiwar songs, and these songs were some of the several highlights of the movie. It’s totally cool to see a film that privileges the antiwar and civilian point of view. The film makes it very clear that the civilians were the ones caught in the crossfire and that there was a significant degree of non-Communist opposition to the war. A lot of people just wanted the war to end, to forget about it, to move on to other things. Forgetting about the war and the past becomes a refrain in Quan’s music, as in this clip (Trinh Cong Son performing an antiwar concert amid armored cars) and the lyrics after that:

When peace returns to our country

I shall visit many sad cemeteries

And tombs covered with grass

When killing ends in our country

Then children will sing on the roads

When peace returns to our country

I shall be continuously on the road

From Saigon to the centre

From Hanoi towards the south

I shall share everyone’s happiness

And I hope to forget the history of my country

A strange sort of highlight in the film is the character of Tim, an American soldier-deserter who Quan befriends and takes to his family home in Hue. The guy speaks fluent Vietnamese. The Vietnamese sounds dubbed, so I’m not sure if that’s really him speaking, but his lips are making the right motions. The point of including Tim is to say that foreigners can oppose the war, and foreigners can belong in Viet Nam, too, if they learn the culture. But who the heck is that guy playing Tim and how did he get in the movie? This is when we would need some extras in the DVD that aren’t there.

Is the film worth watching? Yes. I give it the antiwar stamp of approval. But I also watched it with a former colonel in the ARVN paratroops and no softie on the war question. He was totally into it. The quality of the acting and directing is pretty good, and there are some very nice shots of the Hue landscape. But the ending is a heartbreaker.

_____

“Trịnh Công Sơn, Movie Star: A Review of Đất Khổ (Land of Sorrows)” was originally published on DiaCritics.org on January 11, 2011.

The post Trịnh Công Sơn, Movie Star: A Review of Đất Khổ (Land of Sorrows) appeared first on Viet Thanh Nguyen.

December 9, 2010

This Is All I Choose To Tell: Isabelle Thuy Pelaud’s New Book

From Viet Thanh Nguyen's website, vietnguyen.info

I was twenty-one years old when I started studying for my doctorate in English. Isabelle Thuy Pelaud was a friend of mine, and had started graduate school perhaps a year before me (if you want to see what Isabelle and I looked like in graduate school days, go to the end of this post). Early in my first semester, I went in for a required one-on-one meeting with C, the department chair at Berkeley, a very famous specialist in American literature. I had written a thesis on Vietnamese women’s literature and had read nearly everything available in English by Vietnamese American writers, which wasn’t much in the early 1990s. When C asked me what I wanted to work on in graduate school, I said, Vietnamese American literature. He said, “No, you can’t. You won’t get a job.” What was I supposed to say to that? I went to a mentor in the department, a suave Marxist, and told him of C’s opinion. My mentor said, “C may be conservative, but he’s not dumb.” As in: there was no professional future in Vietnamese American literature.

“Pelaud has produced the first book specifically devoted to Vietnamese American literature. The poignancy of this benchmark is not to be missed. Her book is a timely contribution to the field of Asian American literary studies and to the emergent subfield of Vietnamese American literary and cultural studies. She makes Vietnamese American literature readily visible for readers who are interested in finding an anchor through which to wrestle with this corpus of cultural work. I have a deep appreciation for what Pelaud has done.”

—James K. Lee, Associate Professor of Asian American Studies, University of California at Irvine, and the author of Urban Triage: Race and the Fictions of Multiculturalism

So here we are nearly twenty years later, and a lot has changed. We have the first book on Vietnamese American literature, Isabelle Thuy Pelaud’s this is all I choose to tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature. The title comes from a poem by Truong Tran. The book arrived in the mail the other day, and it’s a sleek book, featuring cover art by Binh Danh, the cover designed by Viet Le. Pelaud and Le are members of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network, Binh Danh is an artist we all know is going to blow up, and Truong Tran is an old stalwart on the literary scene. In many ways, then, the book feels like a product not only of Isabelle’s tireless commitment to Vietnamese American culture but also of an entire collectivity of people working in different ways to forward their own visions and through them, Vietnamese American culture.

“Immediately indispensable, exactingly researched, and beautifully written, This Is All I Choose to Tell is both an introduction to and a road map for an expansive analysis of Vietnamese American literature. By carefully and judiciously introducing her personal story and journey from immigrant to academic, Pelaud has created a work that is both necessary and brave.”

—Monique Truong, author of The Book of Salt and Bitter in the Mouth

I read Isabelle’s manuscript for the book a couple of years ago and knew it was going to make a difference. It’s foundational, as in clearing the way for other scholars to talk about Vietnamese American literature, creating a touchstone for professors who can teach Vietnamese American literature to their students, and identifying for young or aspiring writers the very possibility of such a thing as Vietnamese American literature. The book isn’t hard to read, and I mean that as a compliment, so go out and or give it to an aspiring writer so that person can know he or she is not alone. If you’re in San Francisco or the Bay Area, come to the DVAN fundraiser and release party for the book on January 14th at Andrew Lam’s condo complex (more info here). Food, drink, music, dancing, lots of readers, cameos by Elaine Kim and David Palumbo-Liu, heavyweights of Asian American cultural criticism, news of DVAN’s forthcoming anthology on diasporic Southeast Asian women’s art and literature, and a book signing by Isabelle herself.

Isabelle and I in graduate school, mid-1990s

_____

“This Is All I Choose To Tell: Isabelle Thuy Pelaud’s New Book” was originally published on on December 9, 2010.

The post This Is All I Choose To Tell: Isabelle Thuy Pelaud’s New Book appeared first on Viet Thanh Nguyen.

November 29, 2010

Eye-Level: The Photographs of Jamie Maxtone-Graham

From Viet Thanh Nguyen's website, vietnguyen.info

I saw Jamie Maxtone-Graham’s work long before I met him. I didn’t know his was the work I was seeing. This was back in the early 1990s, when Tiana Thi Thanh Nga was taking her highly entertaining documentary “From Hollywood to Hanoi” on the road and came to Berkeley, where I was studying. This was probably the second documentary by a Vietnamese American filmmaker about Viet Nam (the first probably being Trinh T. Minh-ha’s formidable “Surname Viet Given Name Nam”). Anyway, Jamie shot Tiana’s doc as the cinematographer. He also had a hand in shooting Tony Bui’s “Three Seasons” and Timothy Bui’s “Green Dragon.” But I still didn’t know who he was. Flash forward to the present. Nguyen Qui Duc found out I was coming to Viet Nam this past summer, and asked if I would do a favor for a friend. So that’s how I ended up carrying an expensive camera lens several thousand miles across the Pacific and handing it off to Jamie at Duc’s bar, Tadioto, otherwise known as Rick’s Café Américain for the Hanoi set.

I’m glad I met him. He’s got a great eye, which means more than just being able to take a technically competent photograph. I checked out his photographs before seeing him in Hanoi, and was impressed by his Long Bien series. These are photographs of the people who live around the Long Bien bridge in Hanoi. These are not the kind of people, and this is not the kind of neighborhood, who appear in your Vietnam Airlines travel magazine. Most of the urban neighborhoods in big and small cities look like this one, and most of the people look like these people. That’s what I mean by having a good eye–looking beyond the usual way Viet Nam gets captured in photography, which is, for the most part, about war, tourism, and the anthropology of rural people, especially minorities. So I’m very pleased to show some of his work. He’s been doing feature films, commercials, episodic TV shows, and indie films for over 20 years. Jamie has a few comments below.

- Viet Thanh Nguyen

The photographs here represent a selection of images drawn from four portfolios made in Vietnam beginning in 2007. I moved to Hanoi that year and began shooting State of Youth, a series funded by a Fulbright research grant about contemporary youth culture in Vietnam. In some ways, it is a series I have not finished making and elements of it seem to persist in every body of work I have made since without having to work at it.

The series following were Across Long Bien – photographs in the communities adjacent to the Long Bien Bridge, Rented White Gowns – images of public wedding photography, and When Evening Comes – portraits made at night. All of these works have been made predominantly in Hanoi.

More can be seen at http://www.jamiemaxtonegraham.com

–Jamie Maxtone-Graham

“Eye-Level: The Photographs of Jamie Maxtone-Graham” was originally published on DiaCritics.org on November 29, 2010.

The post Eye-Level: The Photographs of Jamie Maxtone-Graham appeared first on Viet Thanh Nguyen.