Richard Foreman's Blog, page 4

March 8, 2018

Relatively Little Noir - thoughts on my work after reading M John Harrison

Invited to review it for the estimable ‘Tears in the Fence’ magazine, I have recently finished reading M. John Harrison’s collection of stories and short pieces titled: ‘You Should Come With Me Now’. Though aware of MJH and having read some of his stories but none of his books over the years, I had mixed feelings about what I’d read. However, you can read about those as and when the review gets published – hopefully later this year.

But it did get me thinking about some aspects of writing and why, in my own, I make certain choices and not others.

M. John Harrison has embraced the word ‘hauntology’ to describe some aspects of his work. I first came across this term in the early 2000s in association with arty music ventures by the bands Broadcast and The Focus Group. It seemed to relate to their interest in 1970s visions of the future in TV drama series such as ‘The Survivors’ and the later ‘Quatermass’ productions, with musical reference to the BBC Radiophonic workshop and it productions. The word now has a fairly sophisticated definition in Wikipedia: ‘The term refers to the situation of temporal, historical, and ontological disjunction in which the apparent presence of being is replaced by a deferred non-origin, represented by "the figure of the ghost as that which is neither present, nor absent, neither dead nor alive.".’ How you get from the first reference to the latter, I leave with you – but Harrison I think is talking about the latter. Many of his stories play on a sense of liminal presence that is never quite clearly defined.

The ones I felt were most successful were not easy or comfortable reading. Nor I suppose are conventional horror stories, but they tend to be a form of entertainment on the whole - the cerebral equivalent of a roller coaster ride, you might say. The stories that affected me in Harrison’s book lacked that sense of visceral satisfaction (if that’s what you get). Instead, I felt, they delved into all the layers of human corruption – in the broadest possible sense of the word. Physical and mental illness, obsessive thoughts and behaviour, alienation, disjunction, etc. They left me with a queasy feeling, which – on the positive side – disrupted my complacency, but at the same time made me uncomfortable with the very state of being human.

Clearly something of an acquired taste! Another writer whose work frequently delves into this mire is Alan Moore, but I have the advantage of knowing Alan well enough to know that his moral compass can be trusted. His horrors have a purpose and are often balanced by the beatific. Harrison I can’t be so sure about – especially where his stories lose me, as a good few did.

Okay, so the question is – this is interesting material, why don’t I explore it more myself in my stories? I don’t completely shy away from it, as there are certainly a few of the stories in ‘Wilful Misunderstandings’ which touch on this territory. But my tendency is to add other elements, humour being a primary one. (I should add that there is humour in Harrison’s book but it is very dark and dry.) So my story ‘Marinating Jeff’ could conceivably be a Harrison scenario, but my choice of storytelling mode was curiously lighthearted. Why? I’m not sure – maybe it was the only way I could handle the material.

But the majority of the stories take in a more positive approach to human nature. It’s not that I feel some kind of fuzzy, new-agey view of my fellow human beings – far from it. I think we have let ourselves become well and truly fucked by corporate capitalism and by far the majority of us have our heads buried in the sand about it. What we think of as ‘civilisation’ has proved entirely dysfunctional. Nevertheless, on an individual level and often at a local community level, I find I can’t help liking and loving my fellow human beings.

There is a saying: ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions’ and I don’t doubt there is truth in it. But without good intentions, I think we’d have arrived in hell already. So let’s not under-value them. I can’t put a figure on it, but I suspect that most of us try to live good lives. Our understanding of the situation may be too poor to be in any way effective, but we try to do right by our fellow human beings and the planet on which we depend. There’s a lot of self-delusion in this of course and I include myself amongst the deluded. With a more enlightened system of education, and relieved from ever-insidious corporate propaganda designed to keep us consuming, we could conceivably do better. So I don’t want to lose myself in cynicism and negativity. I want to celebrate people, as well as explore their failings.

Looking into the dark side has its values – our perspective is skewed if we ignore it or try to hide away from it. I’ll confront it in my writing when it seems appropriate (certainly the novel I’m working on has some very dark aspects). But I’ll leave it as much as I can to those who probably do it better than me.

Tough job. Someone’s got to do it. Thank-you Alan, thank-you MJ, and also William Burroughs, Albert Camus, Jean Genet, Jim Thompson, Samuel Beckett – to name but a few predecessors - for going there, finding something worth saying and bringing it to the attention of at least some of the reading world. I’ll continue to follow my own intuitions, in somewhat more well-lit land.

M John Harrison

Published on March 08, 2018 06:58

February 19, 2018

Mr and Mrs Mystery

Oh Mister Mystery

I’m in your constant ministry

Open up your canister

& show me something sinister

Bring me things I can’t describe

Carvings from some tattooed tribe

Deposits from a distant star

That shouldn’t be but somehow are

And as though unmeant to linger here

Let them all one day disappear

Or stretch apart my mental range

With something cute but rather strange

That has migrated too far north

And now meanders back & forth

Treading only obscure paths

It can’t be caught in photographs

With tales of odd amnesiacs

Seers and synaesthesiacs

Folk who dress as bears & cats

Wolverines & tangle-tailed rats

Let me peer through dark partitions

At those who’ve lost all inhibitions

Oh Mrs Mystery

I need your subtle palmistry

Open up your bag of tricks

Throw miracles into the mix

Show me frogs in great profusions

Falling from blue skies

Show me statues with contusions

As tears of blood drip from their eyes

Mandala cut in wheat field scene

The name of God in an aubergine

Experiments with weird results

Which folk would rather think were lies

You’ve stuff to start the strangest cults

But I have found it no surprise

As through your secrets I still dive

Much stranger yet

to be

alive

I’m in your constant ministry

Open up your canister

& show me something sinister

Bring me things I can’t describe

Carvings from some tattooed tribe

Deposits from a distant star

That shouldn’t be but somehow are

And as though unmeant to linger here

Let them all one day disappear

Or stretch apart my mental range

With something cute but rather strange

That has migrated too far north

And now meanders back & forth

Treading only obscure paths

It can’t be caught in photographs

With tales of odd amnesiacs

Seers and synaesthesiacs

Folk who dress as bears & cats

Wolverines & tangle-tailed rats

Let me peer through dark partitions

At those who’ve lost all inhibitions

Oh Mrs Mystery

I need your subtle palmistry

Open up your bag of tricks

Throw miracles into the mix

Show me frogs in great profusions

Falling from blue skies

Show me statues with contusions

As tears of blood drip from their eyes

Mandala cut in wheat field scene

The name of God in an aubergine

Experiments with weird results

Which folk would rather think were lies

You’ve stuff to start the strangest cults

But I have found it no surprise

As through your secrets I still dive

Much stranger yet

to be

alive

Published on February 19, 2018 04:10

February 5, 2018

Getting Real in Bethnal Green

At the start of what was to be the heatwave summer of 1976, I was a confused 23 year old would-be hippie, wondering what to do with my life. Intending to learn about social work, I took a voluntary post for 6 months as a ‘warden’ in a half way house for ex-psychiatric patients in Bethnal Green, East London, just round the corner from the famous Brick Lane Market. Nicholas House, the hostel, was a substantial end-of-terrace four storey Edwardian building housing about 20 residents plus some live-in staff. I learned a lot about psychiatric social work during those scorching months and the principle lesson was that I couldn’t hack it. I was deeply naïve and very much steeped in the teachings of RD Laing, whose work is generally discredited now. Laing was a radical psychotherapist, and in books such as ‘The Divided Self’ and ‘The Politics of Experience’ put forth challenging views. Psychosis, for example, was a journey within, a human response to the pressures of living in 20th century society and to intrinsic flaws that developed within families.

The appalling situation of the residents of Nicholas House and other mental illness sufferers I met in East London at that time, seemed to me to bear out Laing’s ideas. The organisation that ran Nicholas House, then known as the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, was I’d guess a pioneer of ‘care in the community’. This concept was taking off, as large psychiatric institutions were beginning to close down. The PRA ran day and evening centres, lunch clubs, ‘industrial education’ sessions and even provided sheltered employment (making plastics products) for those in need of care. A stated aim was ‘to stimulate the patient towards greater initiative and social awareness of his environment and society’.

This was laudable, of course, but the great majority of those with whom they dealt were not in any way ‘cured’ of mental illness, they were ‘stabilised’ on powerful anti-psychotic drugs. One of my daily duties there was to hand out the tablets and ensure that they were taken. The medication tended to make people perpetually sleepy, apathetic and withdrawn. With a few exceptions, they were virtually impossible to ‘galvanise’ or ‘activate’ as I was frequently chided by my superiors to do. And what did the community really have to offer them? Getting a job was seen as desirable, but the jobs that were available (if at all) were dreary production line drudgery – hardly conducive to mental health. Enough, I felt, to drive anyone mad. One day I wrote in my journal: ‘Another day goes through the motions in Bethnal Green. The residents march irresolutely to work or day centres. Close to entropy, they follow the line of least resistance five mornings out of every seven.’

Another of my duties was to take residents for assessment sessions at a nearby psychiatric hospital, primarily with a Doctor Denham. Austrian in origin, he spoke just as cliché psychiatrists do in comedy films in a pronounced Germanic accent, vs instead of ws, and phrases punctuated frequently with the question “Ja?” My initial reaction to Dr Denham was one of dislike. He was another authority figure, like my superiors in the PRA who I’d come within a few weeks to loathe.

I was not alone in this. Most of the paid staff – although dedicated to their work - were unhappy. There was no clear salary structure, no transparency as to how funding was being used and they felt their own ideas were not being listened to. They were members of the NUPE, but the PRA refused to recognise the union. Those who participated in a one day strike to protest about this were summarily dismissed the following day. It was not good practice. And, despite the rhetoric, I found my superiors’ attitude to the mentally ill both patronising and unrealistic.

However, after a few sessions at the hospital, I began to revise my opinion of Dr Denham. I noticed how he recognised and treated each person he saw as an individual. That he could do little more than prescribe medication, I felt, was more a reflection of the pressure he was under than of his preferred policy. He could be humorous at times. He also let slip that he too had a low opinion of my superiors at the PRA. (Essentially I learned that their service was contracted by the NHS because it was the cheapest on offer.)

I found myself wondering what he might have to say about Dr Laing and his radical psychiatry, but there was little opportunity to ask and despite my growing respect for him, I still found him a little intimidating. My own pro-Laingian stance was, despite all the seemingly supportive initial evidence, becoming a little shakier. I’d been tasked, as part of my induction, to produce a sort of essay on the work of the PRA and did so, voicing my criticisms. In an appendix (yes, an appendix, - God, I was pompous!) I’d quoted Laing. When my piece was returned to me, a question appeared below the quotation. “Why is Laing in private practice?” It was, I had to admit, pertinent.

I’d become quite fond of one of the residents. D-, a big man but always neatly dressed in suit and tie, was insightful and witty. You could have mistaken him for a successful businessman. You’d certainly wonder why he was in Nicholas House at all. One day he decided to stop taking his medication. Though I had to toe the line and try to discourage him, I secretly applauded his decision. “Right on, D-!” I thought. Within a few weeks he’d ceased to shave, wash or leave the hostel and was wandering about ranting aggressively and incomprehensibly. He was sectioned. The last I saw of him he was being virtually frog-marched into an ambulance, yelling for the police.

Confusion, as it so often does, was descending upon me. At last, towards the end of my stint, I got a chance to ask Dr Denham about RD Laing and his views. According to my notes made at the time, this is what he said: “People can haff too much insight, ja? Most people go through life viss delusions about ze self -–so vhy make patients see vhat they don’t vant to see?” And of Laing specifically he told me: “I vass the the von who vass left to deal viss RD Laing’s failures.”

I don’t know how true this was. But as far as I remember, neither in his books nor in a lecture he gave that I attended a year or two later, did Laing ever admit to having had any ‘failures’. The journey within was apparently for an elite only, not for the working class in Bethnal Green.

An online trawl whilst setting up this piece for the blog reveals that Robert Mullan - whose book 'Mad to be Normal: Conversations with RD Laing' appeared in 1995 and is the closest thing to a biography - has made a film about Laing in the late 60s, due for release in April and starring David Tennant. After writing the above piece, I re-read some of Laing's work and still found myself impressed by much of his thinking. Maybe the book or the film might resolve some of the issues I had back in '76. I certainly look forward to seeing the film.

The appalling situation of the residents of Nicholas House and other mental illness sufferers I met in East London at that time, seemed to me to bear out Laing’s ideas. The organisation that ran Nicholas House, then known as the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, was I’d guess a pioneer of ‘care in the community’. This concept was taking off, as large psychiatric institutions were beginning to close down. The PRA ran day and evening centres, lunch clubs, ‘industrial education’ sessions and even provided sheltered employment (making plastics products) for those in need of care. A stated aim was ‘to stimulate the patient towards greater initiative and social awareness of his environment and society’.

This was laudable, of course, but the great majority of those with whom they dealt were not in any way ‘cured’ of mental illness, they were ‘stabilised’ on powerful anti-psychotic drugs. One of my daily duties there was to hand out the tablets and ensure that they were taken. The medication tended to make people perpetually sleepy, apathetic and withdrawn. With a few exceptions, they were virtually impossible to ‘galvanise’ or ‘activate’ as I was frequently chided by my superiors to do. And what did the community really have to offer them? Getting a job was seen as desirable, but the jobs that were available (if at all) were dreary production line drudgery – hardly conducive to mental health. Enough, I felt, to drive anyone mad. One day I wrote in my journal: ‘Another day goes through the motions in Bethnal Green. The residents march irresolutely to work or day centres. Close to entropy, they follow the line of least resistance five mornings out of every seven.’

Another of my duties was to take residents for assessment sessions at a nearby psychiatric hospital, primarily with a Doctor Denham. Austrian in origin, he spoke just as cliché psychiatrists do in comedy films in a pronounced Germanic accent, vs instead of ws, and phrases punctuated frequently with the question “Ja?” My initial reaction to Dr Denham was one of dislike. He was another authority figure, like my superiors in the PRA who I’d come within a few weeks to loathe.

I was not alone in this. Most of the paid staff – although dedicated to their work - were unhappy. There was no clear salary structure, no transparency as to how funding was being used and they felt their own ideas were not being listened to. They were members of the NUPE, but the PRA refused to recognise the union. Those who participated in a one day strike to protest about this were summarily dismissed the following day. It was not good practice. And, despite the rhetoric, I found my superiors’ attitude to the mentally ill both patronising and unrealistic.

However, after a few sessions at the hospital, I began to revise my opinion of Dr Denham. I noticed how he recognised and treated each person he saw as an individual. That he could do little more than prescribe medication, I felt, was more a reflection of the pressure he was under than of his preferred policy. He could be humorous at times. He also let slip that he too had a low opinion of my superiors at the PRA. (Essentially I learned that their service was contracted by the NHS because it was the cheapest on offer.)

I found myself wondering what he might have to say about Dr Laing and his radical psychiatry, but there was little opportunity to ask and despite my growing respect for him, I still found him a little intimidating. My own pro-Laingian stance was, despite all the seemingly supportive initial evidence, becoming a little shakier. I’d been tasked, as part of my induction, to produce a sort of essay on the work of the PRA and did so, voicing my criticisms. In an appendix (yes, an appendix, - God, I was pompous!) I’d quoted Laing. When my piece was returned to me, a question appeared below the quotation. “Why is Laing in private practice?” It was, I had to admit, pertinent.

I’d become quite fond of one of the residents. D-, a big man but always neatly dressed in suit and tie, was insightful and witty. You could have mistaken him for a successful businessman. You’d certainly wonder why he was in Nicholas House at all. One day he decided to stop taking his medication. Though I had to toe the line and try to discourage him, I secretly applauded his decision. “Right on, D-!” I thought. Within a few weeks he’d ceased to shave, wash or leave the hostel and was wandering about ranting aggressively and incomprehensibly. He was sectioned. The last I saw of him he was being virtually frog-marched into an ambulance, yelling for the police.

Confusion, as it so often does, was descending upon me. At last, towards the end of my stint, I got a chance to ask Dr Denham about RD Laing and his views. According to my notes made at the time, this is what he said: “People can haff too much insight, ja? Most people go through life viss delusions about ze self -–so vhy make patients see vhat they don’t vant to see?” And of Laing specifically he told me: “I vass the the von who vass left to deal viss RD Laing’s failures.”

I don’t know how true this was. But as far as I remember, neither in his books nor in a lecture he gave that I attended a year or two later, did Laing ever admit to having had any ‘failures’. The journey within was apparently for an elite only, not for the working class in Bethnal Green.

An online trawl whilst setting up this piece for the blog reveals that Robert Mullan - whose book 'Mad to be Normal: Conversations with RD Laing' appeared in 1995 and is the closest thing to a biography - has made a film about Laing in the late 60s, due for release in April and starring David Tennant. After writing the above piece, I re-read some of Laing's work and still found myself impressed by much of his thinking. Maybe the book or the film might resolve some of the issues I had back in '76. I certainly look forward to seeing the film.

Published on February 05, 2018 06:04

January 22, 2018

Faking Fakery and Faking Awards

In my blog of November 27th last year I ran a couple of pieces resulting from an attempt to play creatively with the concept of ‘fake news’. Influenced by the work of poets such as Steve Spence, I was looking at what could be done by collaging ‘found text’ from various sources with or without insertions of words that occurred to me during the process. I’d started by looking through a UK newspaper and mashing together headlines to maintain grammatical consistency whilst juxtaposing disconnected content (‘man accused in birthday suitcase struggle’, ‘sales figures play tricks 40 years on’). I’d then attempted to similarly mash up the content of the articles from which I’d lifted parts of the headlines to create a spoof chunk of ‘news’.

In the first of these, ‘cost of living set to a hot samba rhythm’ I cut in content from Wikipedia and phrases or sentences that simply occurred to me in the process of putting it together, in the second, ‘college award is toast’, I took a more austere approach and simply collaged content from the articles on the page from which I’d lifted the headline words.

My purpose was to see what came out of this experimentation and whether it gave any bearing or perspective on the media and particularly around the concept of ‘fake news’ itself. I’m not sure it led to any great revelations but was aware that the second piece in particular demonstrated how convincing the language of reportage can seem, even when it is broken apart and re-assembled into nonsense. There was something about the tone that continued to make it feel like you were reading ‘news’. This, in itself, I found instructive.

Since then, of course, we’ve had the man who has been coining the term for all it is worth over the past year announce his ‘Fake News Awards’ in which it appears that reports (not always actual news articles) were selected by the president and his team in which there were factual inaccuracies. It has been subsequently pointed out that in each case, those inaccuracies were duly acknowledged by those responsible; apologies and corrections were issued once the errors came to light. The whole thing was a further step in a crude strategy of obfuscation, an ongoing attempt to undermine trust in anyone who voices an opinion critical of the regime. Whether this will work for them in the long run, I’ve no way of telling.

The difficulty around it all is that there are often good reasons to distrust the press and media coverage of ‘news’. The very act of transforming information about events that occur in the world into ‘stories’ implies a series of manipulations. What is selected, what is left out, and by what criteria? Whatever their level of integrity, the purveyors of ‘news’ have to sell their product to us in order to make a living – so this becomes a factor in its presentation. The level of complexity in human affairs is such that we may well be incapable of perceiving a true and accurate picture of what is going on, anyway. It’s no wonder we prefer the distraction of trivia, and therefore that’s what a large proportion of our media contains. Years ago, journalist friends of mine used to joke about the ultimate UK tabloid headline – if I remember rightly it went something like: ‘Transvestite Vicar in Last Minute Mercy Dash to Rescue Palace Corgis’. Sounds like one of my mash-ups, doesn’t it? Maybe I should continue this line of research.

But I recognise that now I’ve made myself a part of all this. Those of you who read this blog presumably do so because I provide some level of interest and entertainment – implying a level of shared taste. The views I occasionally express may well coincide with yours. Such things propel us into one of those social media type ‘bubbles’ in which we feed one another only that which we want to hear. We cherry-pick information according to our bias. This too brings a level of fakery into the ‘news’. Is there any way out of the fog?

Personally I can only go back to one of the reasons I gave for writing my book ‘Wilful Misunderstandings’ – to promote the idea of mental flexibility. Neither trust nor distrust any viewpoint completely. If you favour a left-wing approach, don’t close your mind to what the right-wing are saying, and vice versa. Beware of swallowing any information without cross-examining it, no matter how much it appeals to your personal bias. Maintain humility, and a perpetual sense that there is far more that you don’t know than that you do.

It probably won’t help you win friends and influence people, mind. I mean, look what it’s done for me.

In the first of these, ‘cost of living set to a hot samba rhythm’ I cut in content from Wikipedia and phrases or sentences that simply occurred to me in the process of putting it together, in the second, ‘college award is toast’, I took a more austere approach and simply collaged content from the articles on the page from which I’d lifted the headline words.

My purpose was to see what came out of this experimentation and whether it gave any bearing or perspective on the media and particularly around the concept of ‘fake news’ itself. I’m not sure it led to any great revelations but was aware that the second piece in particular demonstrated how convincing the language of reportage can seem, even when it is broken apart and re-assembled into nonsense. There was something about the tone that continued to make it feel like you were reading ‘news’. This, in itself, I found instructive.

Since then, of course, we’ve had the man who has been coining the term for all it is worth over the past year announce his ‘Fake News Awards’ in which it appears that reports (not always actual news articles) were selected by the president and his team in which there were factual inaccuracies. It has been subsequently pointed out that in each case, those inaccuracies were duly acknowledged by those responsible; apologies and corrections were issued once the errors came to light. The whole thing was a further step in a crude strategy of obfuscation, an ongoing attempt to undermine trust in anyone who voices an opinion critical of the regime. Whether this will work for them in the long run, I’ve no way of telling.

The difficulty around it all is that there are often good reasons to distrust the press and media coverage of ‘news’. The very act of transforming information about events that occur in the world into ‘stories’ implies a series of manipulations. What is selected, what is left out, and by what criteria? Whatever their level of integrity, the purveyors of ‘news’ have to sell their product to us in order to make a living – so this becomes a factor in its presentation. The level of complexity in human affairs is such that we may well be incapable of perceiving a true and accurate picture of what is going on, anyway. It’s no wonder we prefer the distraction of trivia, and therefore that’s what a large proportion of our media contains. Years ago, journalist friends of mine used to joke about the ultimate UK tabloid headline – if I remember rightly it went something like: ‘Transvestite Vicar in Last Minute Mercy Dash to Rescue Palace Corgis’. Sounds like one of my mash-ups, doesn’t it? Maybe I should continue this line of research.

But I recognise that now I’ve made myself a part of all this. Those of you who read this blog presumably do so because I provide some level of interest and entertainment – implying a level of shared taste. The views I occasionally express may well coincide with yours. Such things propel us into one of those social media type ‘bubbles’ in which we feed one another only that which we want to hear. We cherry-pick information according to our bias. This too brings a level of fakery into the ‘news’. Is there any way out of the fog?

Personally I can only go back to one of the reasons I gave for writing my book ‘Wilful Misunderstandings’ – to promote the idea of mental flexibility. Neither trust nor distrust any viewpoint completely. If you favour a left-wing approach, don’t close your mind to what the right-wing are saying, and vice versa. Beware of swallowing any information without cross-examining it, no matter how much it appeals to your personal bias. Maintain humility, and a perpetual sense that there is far more that you don’t know than that you do.

It probably won’t help you win friends and influence people, mind. I mean, look what it’s done for me.

Published on January 22, 2018 08:42

January 8, 2018

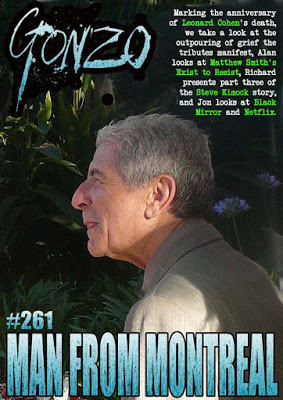

On the Gonzo Beat

‘Gonzo’ magazine, titled with respectful regard to Hunter S. Thompson, appears online on a more or less weekly basis. I became aware of it towards the end of 2016, during some website browsing, and sent a copy of ‘Wilful Misunderstandings’ to see if it would get a review. Intrigued at least by the comments from Alan Moore (for which I remain extremely grateful) on the back cover, editor Jonathan Downes took on the review and gave my book his enthusiastic approval. In subsequent exchanges of messages, Jonathan asked if I’d write for the magazine – to which I agreed on an occasional basis, depending on other commitments.

To knock out a full colour multi-paged mag once a week is no mean feat and if you check it out on http://www.gonzoweekly.com you’ll find that its enthusiastic band of contributors cover a wide range of music and other cultural activities. Its most distinguished writer, I guess, is the one-time Guardian journalist CJ Stone, who contributes a regular column. Short cuts are taken to fill the pages and a number of them remain unchanging issue to issue – ads and random bits of filler mostly. But this seems to me entirely forgivable, given the weekly schedule.

So sometime after the New Year double issue (#215/6) containing the Wilful Misunderstandings review last January I undertook to contribute some features on musicians, primarily those associated in some way with the Grateful Dead, whose music I’ve loved since the 60s. The first of these was lifted from this blog at Jon’s request. It was my personal eulogy and career review for the then recently deceased guitarist Martin Stone (issue 219). Those familiar with Martin Stone will know that even he has some tenuous connections with the Grateful Dead, but my focus was on those with closer associations, including the surviving members of the band. There followed pieces on Phil Lesh (#222), Mickey Hart (#225/6), Warren Haynes (#229) and David Nelson (#233). More recently I’ve contributed an extended piece on guitarist Steve Kimock (#s253, 257 and 261). If you enjoy both the music of 60s and 70s US West Coast bands and today’s ‘jam-band’ scene, you might find some interest in these write-ups.

I’ve also been contributing occasional reviews, beginning with one that fitted my feature remit: musicians Mark Karan, Slick Aguilar, Tom Constanten and others reproducing the ‘Live Dead’ album at the Cheese and Grain in Frome last January (#220). Since then I’ve reviewed a concert by Trad Arrr (#235), Port Talbot’s Deke Leonard memorial show (#239) and the New Forest Folk Festival (#247). A recent piece on the stage show ‘Girl From the North Country’ (#255/6) first appeared here in the blog.

It’s been fun. As with some of the other contributors, I think, it gets the frustrated ‘rock-journalist’ ambition out of my system, and gives me a chance to highlight musicians who don’t these days receive a great deal of attention, particularly here in the UK. I’m currently making a short list of possible profiles to put together in 2018, and may well expand my repertoire.

Meanwhile I look forward to reading through the latest double issue (see below).

Published on January 08, 2018 09:26

December 29, 2017

Failure

Failed to produce my blog on schedule last Monday, can't think why.

Failed to promote Wilful Misunderstandings in the run-up to the festive season, thus depriving myself of a potential sales cascade. So all I can do is appeal to anyone with £6.95 (plus p&p) left to spend after the annual hoopla, with the following ad. (And if you can afford it, buy it from Lepus not Amazon or similar please - cheap as they sell it, I get mere pennies, and I've yet to cover the costs of the printed copies I sell through Lepus...)

No other failures to report.

No other failures to report.

Wishing all readers of this blog a happy new year.

RF

Failed to promote Wilful Misunderstandings in the run-up to the festive season, thus depriving myself of a potential sales cascade. So all I can do is appeal to anyone with £6.95 (plus p&p) left to spend after the annual hoopla, with the following ad. (And if you can afford it, buy it from Lepus not Amazon or similar please - cheap as they sell it, I get mere pennies, and I've yet to cover the costs of the printed copies I sell through Lepus...)

No other failures to report.

No other failures to report.Wishing all readers of this blog a happy new year.

RF

Published on December 29, 2017 07:23

December 11, 2017

We Are Crazy (and not in a good way)

An article in New Scientist magazine (25 Nov, issue 3153, p 12) brought home the impact of something I’ve a tendency to regard in a sort of intellectual way that, normally, does not have an impact on my personal sense of wellbeing. It is that, as a species, human beings – all of us – are well and truly mad.

Under a headline ‘Using bombs to bomb-proof cars’, NS reporter Paul Marks tells us about the work of Roger Sloman, managing director of a company known as ‘Advanced Blast and Ballistic Systems’. Sloman and his team are developing a system intended as a countermeasure to protect the occupants of military vehicles under which improvised explosive devices (IEDs) detonate. Such a blast can, I read, ‘instantly catapult a vehicle many metres into the air’. Because the floors of such vehicles are strengthened, there is less danger from the blast itself than from the intense upward acceleration, which can seriously or fatally damage internal organs.

Research revealed a ten-millisecond gap between the blast and the lifting of the vehicle. The idea is that, in this interval, a detector could trigger roof rockets to provide a downward force to keep the vehicle on the ground. The resulting devices are known as ‘linear rocket motors’ and one of Sloman’s colleagues says: “The peak thrust from all those rocket nozzles is insane.” (Yes. Insane.) In a test one of the vehicles was reckoned to momentarily ‘weigh’ around 120 tonnes.

That life is sacred and that such a device may save lives if it goes into production, I cannot deny. That such technology may have other uses in different contexts is also mentioned in the article. What it does not mention is the cost of research, development and manufacture – which I can only assume must be vast. Our resources on this planet are wearing thin, the fate of the human species is – as far as I can see – in the balance. Why are we blowing thousands, perhaps millions, (plus brain power and materials that could be better used solving humanity’s mutual problems) on peak thrust rocket nozzles?

It highlights for me a number of underlying assumptions. There will always be a need for military vehicles. There will always be people who wish to blast them with improvised explosive devices. There will always be conflict between human beings. Investment in military hardware provides jobs and economic growth and this somehow benefits all of us. I could go on but I’m sure you get the picture. All these statements are interlinked. It’s a house of cards that stays intact because it is part of the consensus we call reality. Is it possible that simply by not accepting these and similar assumptions we could change the picture?

But this article had the effect of renewing and refreshing my sense of shock at what we humans routinely do to one another. Palestine. Syria. Yemen. Afghanistan. Iraq. The playing fields for war games. News of conflict has a numbing effect by its very persistence. It takes a bizarre story about a hi-tech design to anchor against explosive force (and the sense of black absurdity that surrounds it) to brush away the cobwebs of complacency once more.

(from ABBS website)

Published on December 11, 2017 06:03

November 27, 2017

Fake News Faked

Cost of living set to hot samba rhythm

According to a new report by the Office for National Statistics, a marked rise in the retail price index has caused the cost of living to soar unexpectedly. It is currently cruising at an altitude of ten kilometres where Standard atmospheric conditions are −50°C and 26.5 kPa, exceeding the speed of delight. Up there the samba winds blow hot and spicy, although legislation is called for regarding the illicit use of high altitude drones.

The cost of living is now a Brazilian musical genre and dance style, with its roots in African religious traditions, particularly of Angola and the Congo. A spokesperson today spoke of spokes, spoken, smoked and "wholeheartedly" apologised for "any inappropriate behaviour that made some former colleagues feel uncomfortable". He later added that talks at the end of the two-day summit remained incongruous, and that a former leader, at the leading edge, lead the leaders to swing the lead.

The government is considering the modern samba that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. It is predominantly in 2/4 time to a batucada rhythm, with various stanzas measured in terms of purchasing power parity rates. In keeping with leading edge thinking, the term ‘cost of living’ itself shall from hereon in be known as the ‘costa livin’.

College award is toast

One of the UK’s biggest bakers has warned that attempting to redress the bitter legacy of slavery is “unsustainable”. Oxford’s All Souls College is partly governed by overseas prices. Bread unwittingly contributed to the college’s success. Today , 42% of Britons commemorate the suffering of low-carb diets, from protein pots and salads to sushi. Associated British Foods is said to be considering further action to limit carb intake and protest against the commemoration of Cecil Rhodes. New graduate scholarships will reduce the space devoted to bakery items within the next 18 months.

The change is being led by young people, with only a quarter of 16- to 24-year olds eating “distinguished fellows” including former Conservative cabinet ministers John Redwood and William Waldegrave. A spokesperson for the college said: “All Souls is pleased to be equating to a loss of about 23m kilograms. The volume of bread rolls and freshly baked bread sold expresses our present –day values.”

Warburton’s, the UK’s other leading baker, attracted student protests. A student in chains stood outside the research firm Mintel. “Bread is on the firing line,” said a food and drinks analyst at Mintel, “we don’t think the steps All-Souls has taken are enough.” Avocado toast may be an Instagram sensation but has appeared in the Paradise Papers, investing funds offshore in bakeries, making them one of the lowest-cost operations in the country.

According to a new report by the Office for National Statistics, a marked rise in the retail price index has caused the cost of living to soar unexpectedly. It is currently cruising at an altitude of ten kilometres where Standard atmospheric conditions are −50°C and 26.5 kPa, exceeding the speed of delight. Up there the samba winds blow hot and spicy, although legislation is called for regarding the illicit use of high altitude drones.

The cost of living is now a Brazilian musical genre and dance style, with its roots in African religious traditions, particularly of Angola and the Congo. A spokesperson today spoke of spokes, spoken, smoked and "wholeheartedly" apologised for "any inappropriate behaviour that made some former colleagues feel uncomfortable". He later added that talks at the end of the two-day summit remained incongruous, and that a former leader, at the leading edge, lead the leaders to swing the lead.

The government is considering the modern samba that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. It is predominantly in 2/4 time to a batucada rhythm, with various stanzas measured in terms of purchasing power parity rates. In keeping with leading edge thinking, the term ‘cost of living’ itself shall from hereon in be known as the ‘costa livin’.

College award is toast

One of the UK’s biggest bakers has warned that attempting to redress the bitter legacy of slavery is “unsustainable”. Oxford’s All Souls College is partly governed by overseas prices. Bread unwittingly contributed to the college’s success. Today , 42% of Britons commemorate the suffering of low-carb diets, from protein pots and salads to sushi. Associated British Foods is said to be considering further action to limit carb intake and protest against the commemoration of Cecil Rhodes. New graduate scholarships will reduce the space devoted to bakery items within the next 18 months.

The change is being led by young people, with only a quarter of 16- to 24-year olds eating “distinguished fellows” including former Conservative cabinet ministers John Redwood and William Waldegrave. A spokesperson for the college said: “All Souls is pleased to be equating to a loss of about 23m kilograms. The volume of bread rolls and freshly baked bread sold expresses our present –day values.”

Warburton’s, the UK’s other leading baker, attracted student protests. A student in chains stood outside the research firm Mintel. “Bread is on the firing line,” said a food and drinks analyst at Mintel, “we don’t think the steps All-Souls has taken are enough.” Avocado toast may be an Instagram sensation but has appeared in the Paradise Papers, investing funds offshore in bakeries, making them one of the lowest-cost operations in the country.

Published on November 27, 2017 08:38

November 14, 2017

Mirror Lore

I had a close shave the other day. After the soap suds were scraped away, there was my face, craggier and more laden with jowl than I’d really be happy to see. I looked deep into my eyes and, curiously enough, my eyes looked back into me. I wondered what I was really looking at, what was looking at me. Light cast back from whence it came by a cunningly engineered combination of glass and silvery metal? Or was there something about this experience that went deeper? It seemed I had some research to do.

I had a close shave the other day. After the soap suds were scraped away, there was my face, craggier and more laden with jowl than I’d really be happy to see. I looked deep into my eyes and, curiously enough, my eyes looked back into me. I wondered what I was really looking at, what was looking at me. Light cast back from whence it came by a cunningly engineered combination of glass and silvery metal? Or was there something about this experience that went deeper? It seemed I had some research to do.I started with some vampire lore. These pasty-faced, bloodsucker types, it states, have no mirror image. It would appear that Bram Stoker may have been the originator of this idea. It is based in part on the concept that the mirror gives a reflection not just of one’s appearance but also of the soul, thus vampires being soulless have no reflection. A pseudo scientific explanation by modern fantasists has it that it is down to the silver backing in old mirrors – silver having properties to ward off evil – and thus since modern mirrors do not use silver, vampires can scrub their fangs and brush their hair, safely reflected, like the rest of us.

The mirror as portal is an established motif – whether it goes any further back than Carroll’s ‘Through the Looking Glass’, I don’t know. As an image it is used to great effect in Jean Cocteau’s film ‘Orphee’, in which Death is personified as an elegant, fashionably dressed French woman. She and her assistants emerge from and return to the Underworld through mirrors. Scenes in which this occurs were shot horizontally, using framed pools of liquid. For all the crudity of this technique, in comparison to what can be done today with computer graphic imagery, there is something about its conceptual simplicity that creates a sense of extraordinary beauty and other-worldliness. For this and its many other beauties, I never tire of watching this film.

Before I leave ‘Orphee’, here is a quote from its script: ‘Mirrors are the doors through which Death comes and goes. Look at yourself in a mirror all your life...and you'll see death at work like bees in a hive of glass.’ The first sentence deals with what I have described, in the second mirrors are considered as monitors of an inevitable process, a slow revelation of what we are, not only in the spatial dimensions but also in the dimension of time. Or something like that, anyway.

The mirror or the reflective surface crops up frequently in myth, legend and literature. A quick trawl takes us through Narcissus, whiling time by staring at his reflection in a pool; Snow White and the mirror on the wall; the Lady of Shallott viewing Camelot through a magic glass and many a scary story in which something is seen in the mirror which is not apparent elsewhere. Then, of course, we have the common belief that breaking a mirror brings a seven year period of ill-fortune. Seven years? Again we are looking at the mirror as a reflection of the soul, its breakage the breakage of the soul, and the seven year period being the time it takes – it is said - for the soul to regenerate. It is therefore somewhat lacking in apparent logic that various antidotes to this problem are listed involving grinding the shards of mirror to dust or burying them. With regard to the soul, I suspect that the devisers of these remedies have not entirely thought it through. But who am I to question superstition? You breaks your mirror and you takes your choice.

There are also traditions in various cultures that, when someone dies, all the mirrors in their household should be covered. Mirrors (perhaps in their role as Cocteau’s portals to the Underworld) can, they say, act as lures and traps for the souls of the newly departed. A handy bit of blanket coverage for a prescribed period of time enables a safe passage to… well… wherever it is that the deceased persons are supposed to be going.

My search for that which is associated with mirrors has been fruitful. A further trawl of mythology across the world would no doubt generate more. So what’s it all about? Thomas Hardy, in a well known poem, peers into his looking glass and views his wasting skin, but his subsequent reflections (pardon the pun) are to do with ageing itself, rather than the act of observation that triggers them. He’s not looking at this wealth of lore we invest in the silvered glass. But it’s there, layered into our mindsets, even if we are not familiar with every last myth, tale or superstition.

Perhaps the potency of the mirror as an image lies in the mystery of human consciousness. We are our own mirrors, looking at ourselves constantly as we parade through our waking lives. Perhaps the pun is no coincidence – the throwing back of light and the going back in thought are intertwined concepts. Hardy can’t look into his mirror without looking into himself.

And it is one of the scientific tests used to determine levels of conscious awareness in other species. Dolphins and other beasts whose intelligence is in evidence are said to be able to recognise themselves and others in a mirror. Frogs, it is generally accepted, cannot do this. A certain level of consciousness is required to both to reflect and to be aware of a reflection.

The mirror, I conclude, is a potent thing. It tells us more than meets the eye.

Published on November 14, 2017 06:22

October 30, 2017

'Abandon the Platform for the Round' RG Gregory 1928-2017

A couple of blogs ago I wrote a little about my time in Word and Action (Dorset) back in the early 1980s and gave a few links to the Wikipedia page for W&A and to sites connected with its founder and leading light, the poet and playwright RG Gregory. About a week ago I heard that he had died.

I’d known he’d been ill and had visited him last year with good friend and ‘Slugger O’Toole’ blogger Michael Fealty. At that time, there was a faint hope that he had been mis-diagnosed, but by the time I heard he’d died I knew this was not the case. Nevertheless I find I am deeply affected by the news. I’m not alone in this – on his Facebook page there are many tributes from family, associates, ex-W&A members and others. (https://www.facebook.com/rg.gregory.5)

‘Greg’ as he was known was a powerful influence on the lives and thinking of many people. I’m not going to attempt a biography or a full list of his achievements here. You can find out more at the sites I gave in the ‘Girl from the North Country’ review blog, or at this – a more recent site that I didn’t remember to add - http://www.rggregory.co.uk/ . What I’d like to add is a few words about some of the ways he affected my thinking and outlook.

One of the main activities of the W&A group was the performance of what became known as ‘Instant Theatre’. It was the embodiment of many of Greg’s ideas. It developed out of experimentation with theatrical forms and participatory theatre that took place, as I understand it, in the 1950s and early 60s. Greg at that time became attracted to working ‘in the round’ which, in his opinion, removed the underlying hierarchy implicit in staged performances. It drew ‘actors’ and ‘audience’ into a closer and more responsive relationship. The shedding of theatrical effects - costumes, scenery, special lighting, sound effects etc – enabled a greater exercise of the imagination and creativity in all participants.

‘Instant Theatre’ took place in the round, and was a genuine and effective attempt to give an ‘audience’ the opportunity to make up a story on the spot, to have it dramatised, and to participate in the performance. Greg felt that many attempts by others to do this fell short because the ‘professionals’ would tend to lead the ‘audience’ towards what they were prepared to do, not what the ‘audience’ was capable of creating given free rein.

It was generally performed by teams of three people. The ‘Questioner’ would introduce the process and elicit the story by means of a question and answer process. As far as was humanly possible, the questioner had the responsibility to make the questions completely open, not to lead the story in any way. S/he was not to assume anything on behalf of those who gave the answers. The questioner would, however, use his/her own judgement as to how much information constituted a scene of the story to be acted out and at that point re-tell what had been gathered so far (inviting its providers to correct any mistakes). Then the ‘audience’ would be invited to join the other two team members in acting out their story. Not only would people (adults and/or children) play the characters, they would also ‘be’ the props. This would continue, scene by scene, over the course of an hour. (In that respect there had to be an element of leading – a reminder that the time and therefore the story would have to come to an end.) Instant Theatre was often huge fun. Sometimes it was chaotic. Often it hit extraordinary levels of profundity.

To work well the questioning had to be a quick-fire process. Instant Theatre was not created out of discussion as to what would make the ‘best’ story. Considered thought was cut to a minimum. In this manner, if it was working well, the stories tapped what Greg (and many others) believed to be the ‘collective unconscious’. They would work on an archetypal level. They would take unexpected forms.

Except when working with younger children, the questioner would ask for answers to be called out, so would have to include anything s/he genuinely heard. This led to the incorporation of contradictory answers. The question always followed – both these answers are right because I’ve heard them, how can they both be true? It invited lateral thinking.

All this was an eye (and ear and mind) opener for me. In Greg’s thinking, the principles applied to more than theatre, they applied to the way we live our lives, the ways in which we organise our society and make our decisions and more. Think it through. The extent to which so many of us live vicariously through our ‘celebrity’ culture, admire ‘personalities’ in general, imagine that ‘charisma’ is a necessary quality in those who seek to lead - all this has its roots in the idea that those people up on the stage are somehow better than us. Are they? Why do we cling to oppositional politics when you could say: how can both answers be true? And if we did, could we find ways to work together for the greater good? Could our politics come up genuinely from people rather than down from politicians manipulating people for their (and their lobbyists’) own ends?

It was, within my own relatively simplistic thinking, questions like these I found myself asking as Greg’s ideas filtered through to me. You can go a lot deeper with them than I have here. Greg’s own writings are lamentably erratically published, but check out the websites I’ve given if you do want to know more. Also a series of conversations recorded on YouTube with Michael Fealty, starting with https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sosY7kMYIag.

It’s a personal and minority opinion, but with Greg’s death I think we’ve lost one of the great thinkers of our time. His work and its value go largely unrecognised, probably because too many influential people have too much by way of vested interest in the status quo he challenged. To acknowledge such a maverick thinker would be tantamount to undermining their own power bases. The apple cart remains upright.

(I’ve written about this in the past tense, but gather there are practitioners of Instant Theatre still operating. How true they are to Greg’s principles, I don’t know. I’d be happy to hear more about them.)

I’d known he’d been ill and had visited him last year with good friend and ‘Slugger O’Toole’ blogger Michael Fealty. At that time, there was a faint hope that he had been mis-diagnosed, but by the time I heard he’d died I knew this was not the case. Nevertheless I find I am deeply affected by the news. I’m not alone in this – on his Facebook page there are many tributes from family, associates, ex-W&A members and others. (https://www.facebook.com/rg.gregory.5)

‘Greg’ as he was known was a powerful influence on the lives and thinking of many people. I’m not going to attempt a biography or a full list of his achievements here. You can find out more at the sites I gave in the ‘Girl from the North Country’ review blog, or at this – a more recent site that I didn’t remember to add - http://www.rggregory.co.uk/ . What I’d like to add is a few words about some of the ways he affected my thinking and outlook.

One of the main activities of the W&A group was the performance of what became known as ‘Instant Theatre’. It was the embodiment of many of Greg’s ideas. It developed out of experimentation with theatrical forms and participatory theatre that took place, as I understand it, in the 1950s and early 60s. Greg at that time became attracted to working ‘in the round’ which, in his opinion, removed the underlying hierarchy implicit in staged performances. It drew ‘actors’ and ‘audience’ into a closer and more responsive relationship. The shedding of theatrical effects - costumes, scenery, special lighting, sound effects etc – enabled a greater exercise of the imagination and creativity in all participants.

‘Instant Theatre’ took place in the round, and was a genuine and effective attempt to give an ‘audience’ the opportunity to make up a story on the spot, to have it dramatised, and to participate in the performance. Greg felt that many attempts by others to do this fell short because the ‘professionals’ would tend to lead the ‘audience’ towards what they were prepared to do, not what the ‘audience’ was capable of creating given free rein.

It was generally performed by teams of three people. The ‘Questioner’ would introduce the process and elicit the story by means of a question and answer process. As far as was humanly possible, the questioner had the responsibility to make the questions completely open, not to lead the story in any way. S/he was not to assume anything on behalf of those who gave the answers. The questioner would, however, use his/her own judgement as to how much information constituted a scene of the story to be acted out and at that point re-tell what had been gathered so far (inviting its providers to correct any mistakes). Then the ‘audience’ would be invited to join the other two team members in acting out their story. Not only would people (adults and/or children) play the characters, they would also ‘be’ the props. This would continue, scene by scene, over the course of an hour. (In that respect there had to be an element of leading – a reminder that the time and therefore the story would have to come to an end.) Instant Theatre was often huge fun. Sometimes it was chaotic. Often it hit extraordinary levels of profundity.

To work well the questioning had to be a quick-fire process. Instant Theatre was not created out of discussion as to what would make the ‘best’ story. Considered thought was cut to a minimum. In this manner, if it was working well, the stories tapped what Greg (and many others) believed to be the ‘collective unconscious’. They would work on an archetypal level. They would take unexpected forms.

Except when working with younger children, the questioner would ask for answers to be called out, so would have to include anything s/he genuinely heard. This led to the incorporation of contradictory answers. The question always followed – both these answers are right because I’ve heard them, how can they both be true? It invited lateral thinking.

All this was an eye (and ear and mind) opener for me. In Greg’s thinking, the principles applied to more than theatre, they applied to the way we live our lives, the ways in which we organise our society and make our decisions and more. Think it through. The extent to which so many of us live vicariously through our ‘celebrity’ culture, admire ‘personalities’ in general, imagine that ‘charisma’ is a necessary quality in those who seek to lead - all this has its roots in the idea that those people up on the stage are somehow better than us. Are they? Why do we cling to oppositional politics when you could say: how can both answers be true? And if we did, could we find ways to work together for the greater good? Could our politics come up genuinely from people rather than down from politicians manipulating people for their (and their lobbyists’) own ends?

It was, within my own relatively simplistic thinking, questions like these I found myself asking as Greg’s ideas filtered through to me. You can go a lot deeper with them than I have here. Greg’s own writings are lamentably erratically published, but check out the websites I’ve given if you do want to know more. Also a series of conversations recorded on YouTube with Michael Fealty, starting with https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sosY7kMYIag.

It’s a personal and minority opinion, but with Greg’s death I think we’ve lost one of the great thinkers of our time. His work and its value go largely unrecognised, probably because too many influential people have too much by way of vested interest in the status quo he challenged. To acknowledge such a maverick thinker would be tantamount to undermining their own power bases. The apple cart remains upright.

(I’ve written about this in the past tense, but gather there are practitioners of Instant Theatre still operating. How true they are to Greg’s principles, I don’t know. I’d be happy to hear more about them.)

Published on October 30, 2017 09:04