Rafael López's Blog, page 7

September 27, 2017

Reaching out to Puerto Rico.

Thinking of our sisters and brothers in Puerto Rico. It’s almost a week after Hurricane Maria and homes are still without power or phone service. Food and medicine are in short supply. Linking to an article in Fast Company with ways to help the people of Puerto Rico in this humanitarian crisis.

September 26, 2017

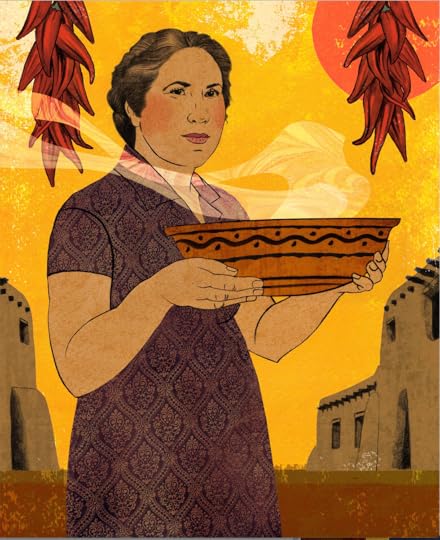

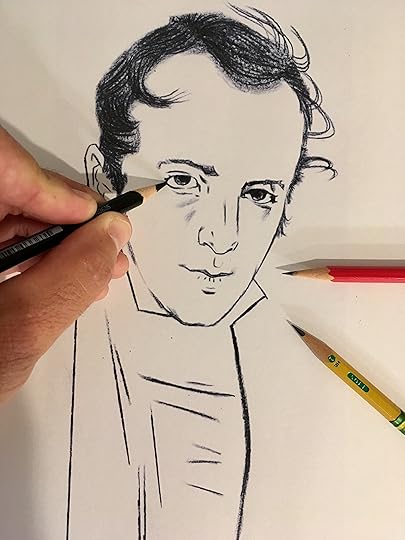

Hispanic Heritage. Fabiola Cabeza de Baca

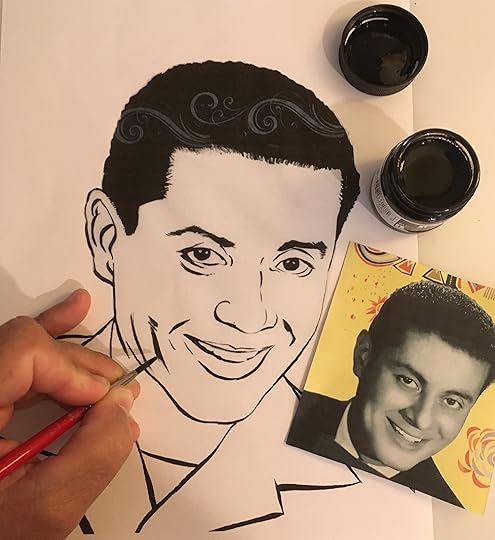

Drawing the portrait of Fabiola for the book Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics.

For Hispanic Heritage Month let’s travel to New Mexico to meet FABIOLA CABEZA DE BACA [1894-1991] who descended from Spanish explorers. She was an American activist, nutritionist, writer and teacher who applied a bilingual approach to her classes adding Latino and Native American history to standard coursework.

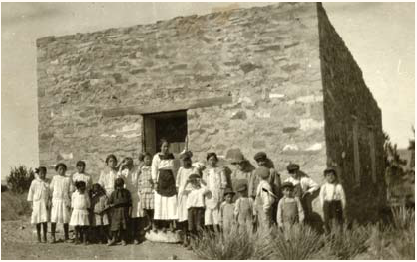

Her family, the Cabeza de Bacas traced their heritage back to New Mexico explorer Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca. In 1912, her uncle was elected and served as the first Lieutenant Governor for the State of New Mexico and then became the second Governor of the state. When her mother died in 1898, she and her three siblings were raised by their father and paternal grandmother. As a child, she grew up wealthy on the family ranch in northeast New Mexico. Women in her family did not perform manual labor but instead did charity work and supervised servants who did the cleaning and cooking. Fabiola rejected typical gender roles and rode her pony beside the horses of her father and grandfather. She got to help out during branding time and when the siblings reached school age, they moved with their grandmother to a mansion made of stone. She longed for the summers when she could hang out with her dad and uncles and escape the needle work her grandmother prescribed. She attended a Catholic school run by the Sisters of Loretto but was expelled due to a confrontation with the nuns in her very first year. Fabiola landed in a public high school and and in 1906 traveled to Spain to study language and history. In 1913 she finished high school with her teaching certificate and despite her father’s protests went to work in 1916 at a rural one room school house.

Fabiola at the rural New Mexico schoolhouse where she taught diverse children.

As it was far from her family ranch, she boarded with a local family. The diverse children who attended her school faced challenging lives and could only attend for part of the year as they had to help their struggling families. She bought her own school materials, taught with out of date books, no bathrooms or running water and used an oil cloth blackboard. She embraced her student’s varied backgrounds that included Spanish speakers with Indian blood, Spanish ancestry and homesteaders. During music class the kids taught each other everything from cowboy and hillbilly tunes to Spanish folk songs.

After getting her degree from the New Mexico public school system in Pedagogy and Romance languages she became intrigued with Home Economics. She liked the idea of bringing both science and productivity to the kitchen and family. She enrolled in a variety of classes including foods, clothing, and chemistry. After moving to Las Cruces she secured her degree in Home Economics from New Mexico State University. Fabiola started to work as an extension agent in New Mexico for Hispanic and Pueblo villages. She brought learning activities to rural locations teaching women modern agricultural techniques, introducing them to sewing machines and organizing clubs. With a goal to help rural families thrive, she was dedicated to her work for thirty years. Cabeza de Baca was the first agent to speak Spanish and often was the agent who translated government information. Fabiola was also the first agent sent out to Pueblos in the Southwest. This was part of the Smith-Lever Act and Smith-Hughs Act of 1914 and 1917. The objective of these acts was to motivate rural Americans to stay on farms instead of heading to big cities for jobs, by improving their lives using science. The state of New Mexico stood out with 82% of the population living in poverty before the Great Depression hit. Most rural women spoke no English and sixty percent were Spanish. As the only Spanish speaking agent, she had plenty of work to do from daylight to darkness.

Among the skills Fabiola taught there was gardening, canning, sewing, home repair and how to raise chickens. Because Fabiola valued tradition she connected to her clients combining the old with the new and integrated contemporary sewing machines with traditional crafts like quilting. She advanced food safety in the southwest teaching rural people in New Mexico to can, dry, and preserve food, making it last longer and decreasing risk of food borne illnesses. She is also credited with organizing markets for Native American women to sell handmade goods for profit. Fabiola married an insurance agent Carlos Gilbert who was also an activist in the League of United Latin American Citizens. After ten years they divorced, but their partnership fueled her participation in the civil rights movement for Hispanics. Fabiola also served as president of the Santa Fe Ladies Council.

Then in 1932, her car was struck by a train injuring her leg which was later amputated. Not willing to let tragedy slow her down, she was back on the road in two years doing her work as an extension agent. She continued traverse rural New Mexico and kept incredible notes about local traditions. In these notes, she recorded everything from herbal remedies to recipes and religious traditions. Some of them were published in the Nuevo Mexicana, a Santa Fe newspaper and she also had a radio program for homemakers. Fabiola loved to cook and her recipes included Indian, Mexican, Spanish and Anglo ideas. When her book Historic Cookery was published it was sent out to other governors to garner publicity for New Mexico. This book was targeted to an Anglo audience and brought attention to the earthy, hearty, simple Southwestern cuisine, prepared mostly with regional ingredients, relying on chiles, beans, squash and corn. The Good Life: New Mexico Traditions and Foods was her second cookbook and put recipes in both historic and cultural contexts.

Cabeza de Baca began writing as social action in the 1940s detailing the cultural traditions of New Mexican villages. Her book, We Fed Them Cactus came out in 1954 telling the stories of four generations of family history in the Southwest. After retirement and as part of the United Nations she created economic programs for Mexico, training workers in techniques she learned working in pueblos and villages. In 1959 she retired to consult for the Peace Corps and became part of La Sociedad Folklorica of Santa Fe, a group dedicated to the preservation of Spanish folklore and culture.

Final portrait for Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics written by Margarita Engle. Fabiola at home in the Southwest.

September 24, 2017

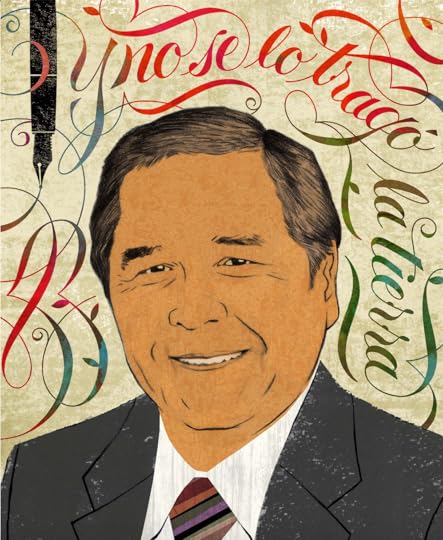

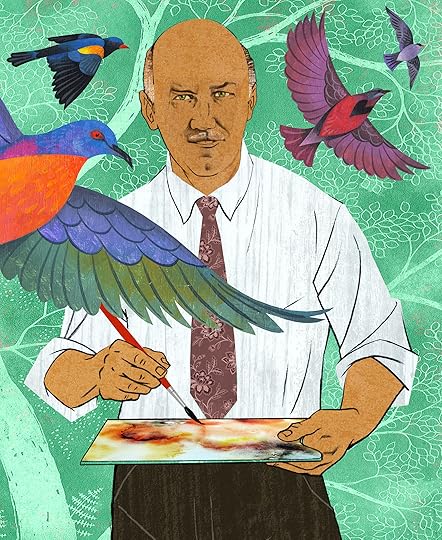

Hispanic Heritage. Tomás Rivera

The arc of the life of TOMAS RIVERA took him from the fields of Texas and the Midwest, to the office of a University of California Chancellor. The son of migrant farm workers, Rivera picked fruits and vegetables till age 20 when he pursued his education full time. He eventually became a Chicano writer, poet and teacher. Tomás began writing at twelve and was an eager reader who valued family. Despite the repetitive challenges and barriers placed in his way he had the courage to overcome adversity and open doors for others through education.

In 1956, he achieved his B.A in English from Southwest Texas University to focus on his writing career instead of migrant work. Rivera published his first novella, made up of fourteen short stories in 1971 called And the Earth Did Not Devour Him. This first work won the Premio Quinto Sol literary prize that recognized and promoted Chicano writers. This notable author and poet never forgot his past and wrote extensively about the life of migrant workers using firsthand experience.He also contributed to a book of poems, Always and Other Poems wrote for the bilingual journal of Mexican-American ideas El Grito. Rivera’s toolbox was filled with perseverance, hard work, intelligence and the power of his pen. Not only did he dedicate his work to helping others attain higher education, he was determined to encourage and create opportunities for Mexican-Americans so they could break barriers in writing and publishing.

As a creative writing teacher he touched numerous lives including my friend, Newbery honor author Margarita Engle. Today I’m sharing illustrations I created for the book Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics that Margarita dedicated to Rivera. He made essential contributions to the Chicano Literary Movement and was deeply concerned about education. As a writer he related the challenges he faced growing up and used them to comment on the struggles of being a minority. His stories were told from the perspective of a young narrator. As the narrator became more aware of the outside world, he understands morality and immorality. Rivera’s characters avoid stereotypes and are unique giving authentic insight into the Chicano experience.

Higher education for Hispanic communities was an imperative for Rivera as he knew it would make a difference for individuals and communities. Rivera worked as a high school teacher throughout the Southwest as well as at Sam Houston State University, and the University of Texas at El Paso. He was more than a great teacher, he was a leader and eventaully served as Chancellor of the University of California, Riverside from 1974 till his death. Tomás Rivera has the distinction of being the first Mexican-American chancellor in the U.C. system.

Rivera was an educational activist and his literary works focused on personal struggles key to advancing Latina/o literature. A blazing comet his career lighted a course of of encouragement for other Latina/o authors to tell their own stories in published works. His own poetic stories were rich with attention to detail and grounded in his own experiences.

An activist, he served as president of the Alamo Valley chapter of the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese and he was a founder of the National Council of Chicanos in Higher Education. He was appointed to higher education commissions by two sitting Presidents. On the board of the Carnegie Institute he also founded the Tomás Rivera Institute for Public Policy on Chicanos in Higher Education based at the Pomona College campus. Santa Clara University awarded him an honorary doctorate and he was named a distinguished graduate by Southwest Texas State University. His reach extended further by serving on the boards of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Educational Testing Service of Princeton, New Jersey.

In 1978 he married Concepción Garza and together they raised three kids.Texas State University College of Education created The Tomás Rivera Mexican American Children’s Book Award in 1995. It recognizes authors and illustrators who create literature that depicts the Mexican American experience.On the Riverside campus, the University of California named the plaza in honor of his legacy. There are 85,000 items in his archive, remarkable because Tomás Rivera was the first person in his family to ever attend college. Rivera had the vision to see that generations of migrant workers could attain higher education, contribute and reach their goals.

September 23, 2017

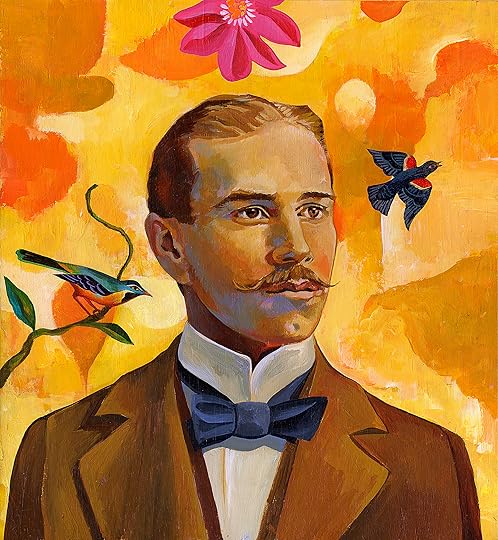

Hispanic Heritage. Louis Agassiz Fuertes

Painting living birds for the portrait of Fuertes in Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics written by Margarita Engle for Henry Holt & Company

LOUIS AGASSIZ FUERTES was an exceptional illustrator, artist and ornithologist who is regarded among the most accomplished American bird artists. Fuertes is credited for pioneering the painting of living birds in natural habitats.

Born to a Puerto Rican father and American mother in Ithaca, New York, Fuertes was fascinated with birds at an early age. This was confirmed when his parents discovered the live owl he brought home and placed at the kitchen table. His father who taught civil engineering at Cornell, took him to the library to study his predecessor John James Audubon‘s stunning, life sized illustrated watercolors in the book Birds of America. That’s when young Louis began drawing birds. He taught himself to keep careful records documenting the look, habits and voices of birds he encountered.

At 17, he was named the youngest member ever of the American Ornithologist’ Union after sending a rare, very accurate specimen he collected to the Smithsonian. He traveled with his parents to Europe, sketching birds and other animals in Paris. He decided to stay for a year in Zurich and study there before returning to America. As his interests in birds and art continued to take flight, his family encouraged him to pursue a regular course of study at Cornell. They felt he could never make a living at art. He agreed to study architecture but but failed math, chemistry and philosophy. During a college lecture, he climbed out the classroom window and sat motionless in a tree, exceedingly curious about a strange, unfamiliar bird call that caught his attention.There was one class however, where Louis not only excelled but took to the sky with perfect grades-drawing. He graduated from Cornell in 1897 and was apprenticed to the painter Abbot H. Thayer, with whom he made his first expedition to Florida in search of birds.

Fuertes worked hard and got noticed with a well deserved break. The nation’s leading ornithologist Elliott Coues decided to mentor the gifted young artist. He opened doors giving Louis access to the academic world and soon Fuertes was getting commissions for his illustrations of birds. Together they traveled to Cambridge England to attend the Ornithological Congress at Cambridge. Then C. Hart Merriam invited the 25 year old to join the Harriman Expedition to wild Alaska. His dreams took wing and the illustrator and ornithologist was determined to collect as many types of birds as possible. He crossed glaciers, tracking native birds through deep woods, sketching as he went. Louis had an intense focus when he painted birds, tuning out the world to produce remarkable full color drawings. His art brought recognition to published volumes of the adventure.

The world is the geologist’s great puzzle-box; he stands before it like the child to whom the separate pieces of his puzzle remain a mystery till he detects their relation and sees where they fit, and then his fragments grow at once into a connected picture beneath his hand.-Louis Agassiz Fuertes

Experimental Portrait created of a younger Louis Agassiz Fuertes while searching for direction.

Word got out about his work got out and Louis got offers to illustrate every significant bird book published in the United States. His works demonstrated incredible skill with distinctive details that marked Fuertes intuitive ability to capture a bird’s natural attitudes and actions. To fuel his work, he traveled across most of America and other countries that included the Bahamas, Canada, Colombia, Ethiopia, Jamaica and Mexico. Louis became a frequent collaborator with Frank Chapman who was the curator of the American Museum of Natural History. Their work together involved illustrations for books, field research and the creation of detailed background dioramas for exhibitions. During a Mexican expedition, Fuertes happened on a new oriole that was named after him. He often lectured at Cornell University sharing his ideas and inspiration with students and faculty.

Fuertes traveled to Abyssinia with Wilfred Hudson Osgood and created enthralling watercolors of birds and mammals there. In 1927 having just returned from another expedition to Ethiopia he drove with his wife Margaret to visit his friend, curator Frank Chapman in New York. After that meeting, his car was struck by a train, concealed at the railroad crossing by stacks of hay. Louis Agassiz Fuertes died in the crash and Margaret was severely injured in the accident. As if by magic, the paintings they carried in the car were completely unscathed and became part of an exceptionally rare collection of Fuerte’s incredible works.

Portrait of Louis Agassiz Fuertes for Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics

As part of his legacy, the Fuertes’s parrot got it’s name from the legendary artist and ornithologist. The Boy Scouts of America also named him an honorary scout in 1927, a distinction given to those “American citizens whose achievements in outdoor activity, exploration and worthwhile adventure are of such an exceptional character as to capture the imagination of boys”. His groundbreaking work influenced many later wildlife artists and in 1947 the Louis Agassiz Fuertes Award was established at The Wilson Ornithological Society. In his time, he painted dozens of illustrations of mammals for National Geographic Magazine which inspired the Society to hire their own artist. The paintings of this singular Hispanic American illustrator continue to inform, inspire and soar.

September 21, 2017

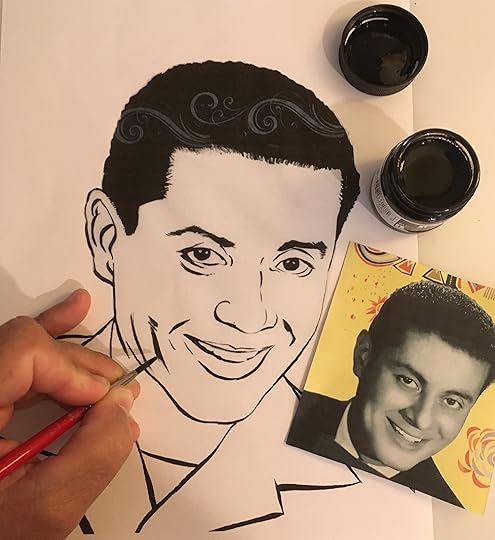

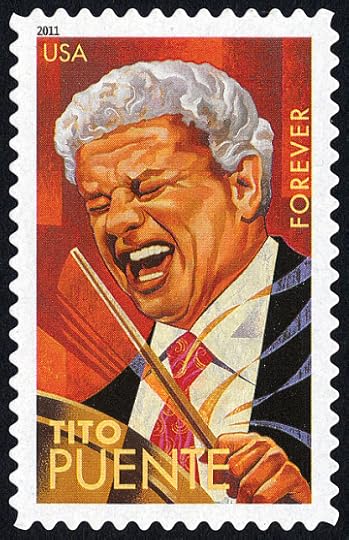

Hispanic Heritage. Tito Puente

TITO PUENTE [1923-2000] pioneered an original sound that mixed mambo and Latin jazz, spanning a 50 year music career. The son of Puerto Rican immigrants, he grew up in New York City. For Hispanic Heritage Month it’s time to pay tribute to the The King of Latin Music. I count myself lucky to have see him perform with unforgettable style once on the streets of San Diego.

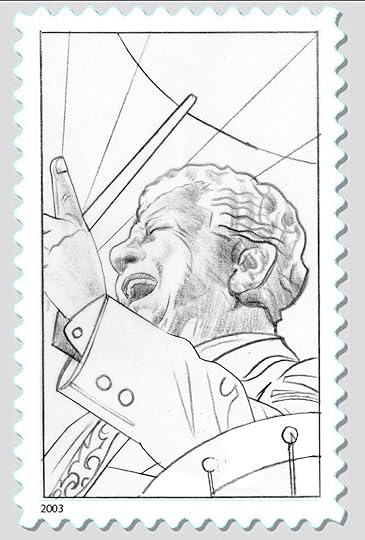

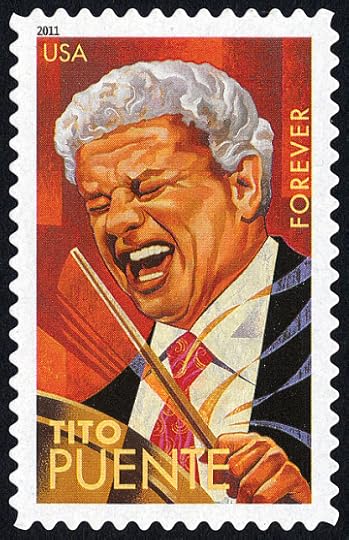

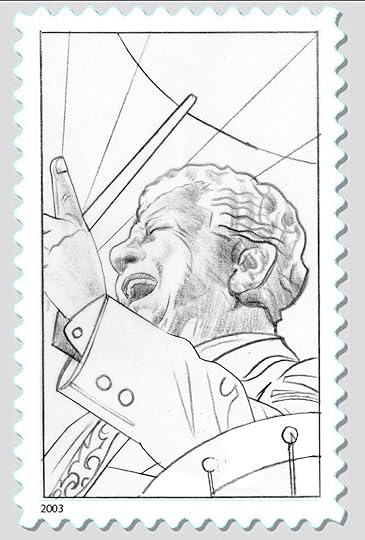

Sketching for the book Tito Puente Mambo King.

A big fan of his experimentation and unique sound, today I’m sharing original illustrations created for the book Tito Puente Mambo King, written by Monica Brown. I’m also including artwork for the Latin Music Legends stamps honoring Puente, that I developed for the United States Postal Service.

This kid had rhythm the day he was born. In the scene below, the eager percussionist gets his start by banging on pots and pans in the kitchen of his Spanish Harlem home.

Young Tito learned to play several different instruments as a child, starting with piano and then percussion followed by saxophone, vibraphone and timbales. He was naturally gifted and became a professional musician and the tender age of 13.

He was apprenticed to the well known Machito Orchestra. Then Tito was drafted into the United States Navy and served aboard ship during World War II.

In 1945, after the war, Puente returned to New York to focus on his musical career. He wisely invested money from the G.I. Bill to further his talents and studied at the famous Juilliard School. Perfecting his craft, by 1948 he had formed the Tito Puente Orchestra. It was typical that a drummer would sit in the back of a big band but not Tito. He put the percussion right up front, timbales, conga and bongo so he could cue the orchestra-he was the leader of the band. As time passed he began to play for larger crowds drawn to his energized, unique sound.

Not afraid to try new things, Puente blended the big band style with traditional Latin dances, jazz and other genres to create musical magic. To the mix, Tito added Afro-Cuban beats, bossa nova, cha-cha, merengue and salsa experimenting with musical ingredients in an innovative way that made you move your feet.

If there is no dance, there is not music. -Tito Puente

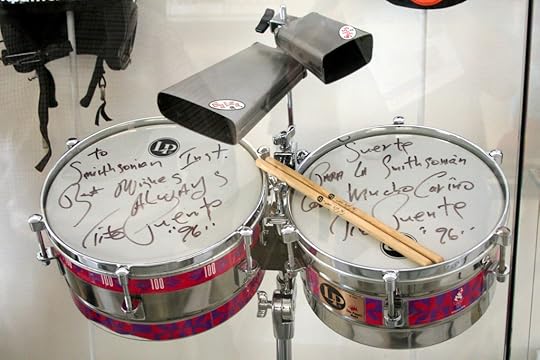

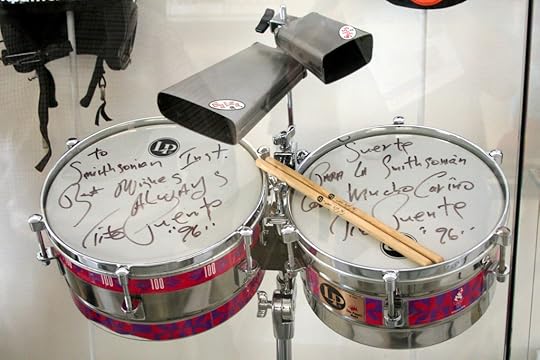

Puente received many awards for his music, including five Grammy Awards. One of his nicknames was “El Rey de los Timbales” which translates to the The King of the Timbales. He went on to guest star on popular T.V. shows like Sesame Street and The Simpsons and his music and charisma made him part of popular culture. Tito appeared in feature films such as The Mambo Kings and Calle 54. He performed with leading jazz artists and symphony orchestras and was given the National Medal of the Arts.

He wrote over 200 compositions, created 2000 musical arrangements and 118 albums. After more than 10,000 live performances he was respected by peers and fans as a musical legend. Perhaps his most famous composition was the mambo Oye Como Va that was made popular by Carlos Santana and later sung by Celia Cruz and Julio Iglesias

He was generous and helped launch many musical careers. Determined to make a difference he dedicated himself to causes beyond music and worked for the Latin community throughout his life. At Juilliard, he created a scholarship for Latin percussionists, determined to fuel the next generation in pursuit of their musical dreams.

Tito Puente died at age 77 and with a worldwide following, his fans waited in line for days to say goodbye. His music and legacy continues.

Courtesy Radiofan at wikipedia

HISPANIC HERITAGE. TITO PUENTE

TITO PUENTE pioneered an original sound that mixed mambo and Latin jazz, spanning a 50 year music career. The son of Puerto Rican immigrants, he grew up in New York City. For Hispanic Heritage Month it’s time to pay tribute to the The King of Latin Music. I count myself lucky to have see him perform with unforgettable style once on the streets of San Diego.

Sketching for the book Tito Puente Mambo King.

A big fan of his experimentation and unique sound, today I’m sharing original illustrations created for the book Tito Puente Mambo King, written by Monica Brown. I’m also including artwork for the Latin Music Legends stamps honoring Puente, that I developed for the United States Postal Service.

This kid had rhythm the day he was born. In the scene below, the eager percussionist gets his start by banging on pots and pans in the kitchen of his Spanish Harlem home.

Young Tito learned to play several different instruments as a child, starting with piano and then percussion followed by saxophone, vibraphone and timbales. He was naturally gifted and became a professional musician and the tender age of 13.

He was apprenticed to the well known Machito Orchestra. Then Tito was drafted into the United States Navy and served aboard ship during World War II.

In 1945, after the war, Puente returned to New York to focus on his musical career. He wisely invested money from the G.I. Bill to further his talents and studied at the famous Juilliard School. Perfecting his craft, by 1948 he had formed the Tito Puente Orchestra. It was typical that a drummer would sit in the back of a big band but not Tito. He put the percussion right up front, timbales, conga and bongo so he could cue the orchestra-he was the leader of the band. As time passed he began to play for larger crowds drawn to his energized, unique sound.

Not afraid to try new things, Puente blended the big band style with traditional Latin dances, jazz and other genres to create musical magic. To the mix, Tito added Afro-Cuban beats, bossa nova, cha-cha, merengue and salsa experimenting with musical ingredients in an innovative way that made you move your feet.

Puente received many awards for his music, including five Grammy Awards. One of his nicknames was “El Rey de los Timbales” which translates to the The King of the Timbales. He went on to guest star on popular T.V. shows like Sesame Street and The Simpsons and his music and charisma made him part of popular culture. Tito appeared in feature films such as The Mambo Kings and Calle 54. He performed with leading jazz artists and symphony orchestras and was given the National Medal of the Arts.

He wrote over 200 compositions, created 2000 musical arrangements and 118 albums. After more than 10,000 live performances he was respected by peers and fans as a musical legend. Perhaps his most famous composition was the mambo Oye Como Va that was made popular by Carlos Santana and later sung by Celia Cruz and Julio Iglesias

He was generous and helped launch many musical careers. Determined to make a difference he dedicated himself to causes beyond music and worked for the Latin community throughout his life. At Juilliard, he created a scholarship for Latin percussionists, determined to fuel the next generation in pursuit of their musical dreams.

Tito Puente died at age 77 and with a worldwide following, his fans waited in line for days to say goodbye. His music and legacy continues.

Courtesy Radiofan at wikipedia

September 20, 2017

Hispanic Heritage. Pura Belpré

Painting in process of Pura Belpré for BRAVO! Poems about Amazing Hispanics

Yesterday I was creating this post about someone who impacted my life, Pura Belpré. For Hispanic Heritage month I want to recount the stories of incredible dreamers and doers, Hispanics who made a difference.

When I heard about the earthquake in Mexico City I put everything down to connect with family and friends in my hometown, some who have lost their homes. The loss of life and destruction to property is overwhelming. Despite all they have been through I heard something familiar in their voices. Something I have always known about Latinos. We are RESILIENT.

Let’s face it, this year Hispanic Heritage month feels different. We’ve been bullied with all kinds of bad names and labels. Hispanic communities are under attack with racial profiling, moves to eliminate affirmative action and aggressive immigration policies designed to bring fear and confusion. Instead of building bridges of understanding all we hear about is walls. Despite the steady stream of negative tweets and taunts, genuine pride in Hispanic heritage does not falter. As a people we Latinos are resilient, we know how to pick ourselves up, rebuild and never quit.

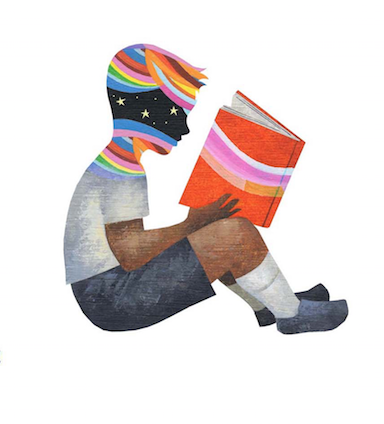

That’s why it is more important than ever for a simple idea. All children have the right to see themselves in the pages of books and hear stories that inspire, challenge and lift them up. Stories they can relate to.

That brings me to our heroine PURA BELPRE. The amazing librarian, activist and storyteller who traveled all around New York, zig-zagging from the Bronx to the Lower East Side. Wherever she went she brought along puppets to tell stories to children in Spanish and English. Today I’m sharing illustrations of Pura from the book BRAVO! Poems about Amazing Hispanics, written by Margarita Engle.

When she arrived from Puerto Rico to attend her sister’s wedding she liked New York and decided to stay. With dreams to become a teacher, her first job was in the garment industry. Her language skills, community spirit and literary skills got noticed. Public libraries needed young women with determination and skill to reach out to diverse communities. Families who spoke Spanish at the time, wouldn’t send their kids to the library because they believed it was only for children who spoke English. She went to the Library School at the New York Public Library in 1925.

Pura was exceedingly clever, a groundbreaker who knew how to engage and delight children. She had gifts and heart and knew how to encourage them to read and fall for books the way she did. She was the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City. An organizer and advocate she set up bilingual story hours, bought Spanish language books and created library based programs focused on Spanish holidays. When Pura discovered there weren’t any books in Spanish for children, she sat down and wrote them. Her stories and storytelling made Spanish speaking immigrants feel at home in the library. She knew if she got them in the door, they would discover rich resources to help them grow their education, skills and careers. She helped transform the 115th Street branch into a vital cultural center for Latinos living in New York. One of the important Latin Americans to visit was Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Pura Belpré with puppets from her own story Pérez and Martina. It was the first book in Spanish published by the mainstream press.

Pura Belpré married African-American composer and violinist, Clarence Cameron White and left the library to go on tour with him and focus on her literary career. When he died, she returned to the library as the Spanish Children’s Specialist, traveling all over the city to reach large populations of Latino children.

Each year, The American Library Association gives the Pura Belpré award to recognize books for kids and young adults by Latino authors and illustrators. At this writing, about 25% of American public school students are Hispanic, yet less than 3 percent of books published for U.S. children are created by Latino illustrators and writers. As an illustrator who has received this incredible award in the past, I can tell you it really does change your life. In the spirit of Pura, the recognition that bears her name, encourages you to keep pushing your craft. It opens doors of opportunity to continue your work with amazing writers and publishers. To connect to libraries, librarians and children.

To tell authentic stories with words and pictures.

September 19, 2017

In solidarity with Mexico City

This afternoon a 7.1 earthquake struck my hometown of Mexico City. I scrambled to reach family and friends and one by one, breathed a sigh of relief to find they had come through. As reports come in we know this quake caused serious destruction and loss of life. Reaching out in solidarity with the people of Mexico City.

Stay strong and safe.

September 18, 2017

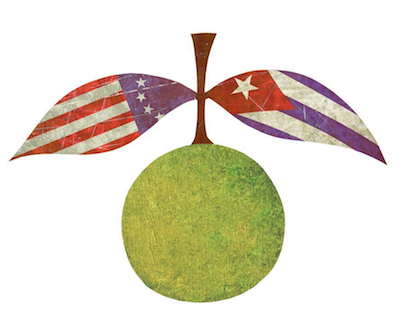

Hispanic Heritage. Juan de Miralles

Born in Spain in 1713, JUAN DE MIRALLES moved with his family as a young boy to Cuba. This portrait was created for the book BRAVO! POEMS ABOUT AMAZING HISPANICS written by Margarita Engle.

Juan de Miralles married into a Cuban family and became a very successful merchant. This prominent businessman was also a passionate champion of independence. During the Revolutionary War, American Colonists were struggling for freedom and desperately needed military and financial support. The King of Spain, Carlos III sent him to help the American revolutionaries and act as an observer. With incredible diplomatic skill he connected to Washington’s most inner circle. Miralles and George Washington became fast friends after they met at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Juan de Miralles gave his full support, finances and connections to the cause of freedom.

As fresh fruit was the cure for scurvy, Washington sought out Miralles assistance to to save the American fleet and soldiers from illness. In response Juan sent his ships back to Cuba returning with life-saving guavas and limes for the troops. Using his Cuban connections he also made sure that American rebels were regularly supplied with arms, uniforms and staples like flour and sugar. He personally lent his own money to several continental towns to aid the war effort against the British. In a secret meeting with Patrick Henry, he helped plan the strategy to defeat British troops in Florida.

Hispanic intervention at such a crucial time in the young history of the nation was vital to the push for independence. Although the story of Juan de Miralles is relatively unknown in the United States, his name is included on a plaque at St. Mary’s Church in Philadelphia together with the founding fathers. A huge loss for the nation, this champion of American independence died of pneumonia at Valley Forge. George Washington led the military parade in his honor and presided over his funeral recognizing the important contributions, courage and determination of his friend.

Many historians believe that if Juan de Miralles had lived, his close relationships with our founding fathers might have changed the course of history between Spain and the United States. His successors were never able to spark the relationships he did. The diplomatic work of Juan de Miralles brought two very different cultures together to benefit them both. This Hispanic patriot delivered imperative aid to help secure independence for the American colonies.

September 17, 2017

Hispanic Heritage Month. Stories Worth Telling

Thanks to Della Farrell of School Library Journal for putting together this inspired list of books for Hispanic Heritage Month.