Robin Abrahams's Blog, page 8

September 24, 2014

Autobiographical memory and H.M.

Do women remember life events better than men?

A better question might be, do little girls get taught to remember better than boys? According to Slate, this might be the case:

Researchers are finding some preliminary evidence that women are indeed better at recalling memories, especially autobiographical ones. Girls and women tend to recall these memories faster and with more specific details, and some studies have demonstrated that these memories tend to be more accurate, too, when compared to those of boys and men. And there’s an explanation for this: It could come down to the way parents talk to their daughters, as compared to their sons, when the children are developing memory skills.

To understand this apparent gender divide in recalling memories, it helps to start with early childhood—specifically, ages 2 to 6. Whether you knew it or not, during these years, you learned how to form memories, and researchers believe this happens mostly through conversations with others, primarily our parents. These conversations teach us how to tell our own stories, essentially; when a mother asks her child for more details about something that happened that day in school, for example, she is implicitly communicating that these extra details are essential parts to the story.

And these early experiments in storytelling assist in memory-making, research shows. One recent study tracked preschool-age kids whose mothers often asked them to elaborate when telling stories; later in their lives, these kids were able to recall earlier memories than their peers whose mothers hadn’t asked for those extra details.

But the way parents tend to talk to their sons is different from the way they talk to their daughters. Mothers tend to introduce more snippets of new information in conversations with their young daughters than they do with their young sons, research has shown. And moms tend to ask more questions about girls’ emotions; with boys, on the other hand, they spend more time talking about what they should do with those feelings.

A few years ago, I was leading a post-show talkback after a production of “Yesterday Happened,” a play at Central Square Theater about Henry Molaison, better known as “H.M.” H.M. was a man born in the 1920s who suffered from severe epilepsy, and the surgery used to cure it–removal of most of his hippocampus and amygdala–also prevented him from ever forming new memories. He lived in 10-minute increments, much like the man in “Memento.” Much of what we know about how human memory works is because of experiments performed on H.M.

Anyway, one of the audience members who stayed for the talkback pointed out that H.M. seemed to have a notable lack of memories from before his surgery as well, and what was up with that?

I said that I didn’t know, but that H.M. reminded me of my father in many respects–the same generation, general ethnic background and social class, IQ and intellectual ambitions, overall temperament–and he hadn’t had a lot of specific memories, either. I pointed out the fact that memory isn’t an automatic recording of events, and that my father simply never bothered to encode a great deal about his own experiences, and you don’t remember what you don’t encode. He was taught to value facts, observable phenomena, and social expectations–not his own personal mythology. He didn’t make a big deal about his life story and the various chapters thereof, the way people do today.

After the talkback, an older man in the audience came up to me and said I was exactly right about the psychology of men of his generation and station in life.

There’s a new play about H.M. in town, if I’ve managed to pique your curiosity! The guy was important–they never write science plays about the subjects of experiments, for heaven’s sake, and H.M. has been the star of two, now! The new one is “The Forgetting Curve,” by Vanda, a Bridge Rep production playing at the Boston Center for the Arts. This weekend they’ve got some great memory experts to lead post-show conversations:

Wednesday, 9/24 – Dr. Howard Eichenbaum; Dr. Daniel L. Schacter

Thursday, 9/25 – Dr. Ayanna Thomas

Friday, 9/26 – Bob Linscott

Saturday, 9/27 – Dr. Bonnie Wong

“The Forgetting Curve” runs through this Saturday. Check it out!

September 23, 2014

“Cartoon dramas,” political & personal

The Globe published a good op-ed this weekend by Meta Wagner, a writing instructor at Emerson, about “cartoon dramas”:

But, now there’s a new, popular TV genre that somehow pulls me in while preventing me from becoming fully invested. I’ve come to think of it as the cartoon drama.

With cartoon dramas, the people, the storylines, and the situations are so unreal — or perhaps hyper-real — as to be laughable, which perfectly befits cartoons but not traditional dramas. These shows (their precursor is “24”) take the most frightening and horrifying political events of the day and present them in an over-the-top, unbelievable, outrageous fashion. It’s television for an age where we’re concerned and terrified yet simultaneously suffering from compassion fatigue: the age of ISIS, ISIL, the beheadings of two American journalists, war in Syria, a do-nothing Congress, the militarization of our police forces, the Ebola virus, etc.

And so viewers not only turn to sitcoms and reality TV to escape, we also turn to cartoon dramas to confront the ugliness of current events, but in a way that can leave us ultimately untouched. Murder, torture, corruption — none of it sticks.

She identifies “Scandal,” “Homeland,” and “House of Cards” as three of the biggest offenders, or perhaps I should say “delighters.” Ever since Bertolt Brecht, we’ve known that while drama inherently draws people in, there are also techniques it can use to push an audience away–not in the sense of disengaging, exactly, but in the sense of making people aware, suddenly or stubbornly, that they are watching a piece of staged entertainment. Brecht called it the “alienation effect.” If you’ve ever seen a show where you can see all the ropes and pulleys backstage, or where the stagehands move the furniture around in plain sight, not trying to be unobtrusive–that’s a little Brechtianism, right there.

Television can’t simply show you the wires and hired help, like theater can, but it has other ways of reminding the audience that this is just a show. (Besides the most obvious one, commercials–which to this day no one has employed to better Brechtian effect than Alfred Hitchcock in 1950s “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” program.) Television can get the alienation effect by being over-the-top, or self-referential, or–and no stage director would dare try this–simply not very good.

I wrote a similar analysis to Ms. Wagner’s about “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit,” which I still consider, pace “Scandal,” to be the finest exemplar of the genre.

An aesthetic style that would continually shift audiences between sentimental empathy and critical awareness is called “epic theater.” It was a groundbreaking idea a hundred years ago, and the smartest theater artists in the world are still exploring this extraordinarily fertile concept today.

“L&O: SVU” achieves epic theater status by the simple expedient of not being very good.

Or, more precisely, being bad in very specific ways that keep the viewer from being overwhelmed by the horror of the actual stories portrayed in the show. Those stories, and the actors who play them–those are often very good indeed.

In the episode “Disabled,” for example, the detectives watch a video recording of a caretaker beating a paralyzed woman with a bar of soap in a sock. The woman in the wheelchair has advanced multiple sclerosis; she can feel the beating, but not dodge or even scream beyond choked moans and grunts. The video goes on for several minutes, one woman mercilessly pounding another across the head, face, breasts. The detectives are repulsed–even Ice-T is visibly shaken. The video cuts out.

After a moment of silence, the forensic psychiatrist, Dr. Huang, speaks. “I think Janice deeply resents having to care for her sister.”

YOU THINK? Let me tell you, Bertolt Brecht is kicking himself in his grave, if such a thing is possible, for not putting Dr. Huang in “The Good Woman of Szechuan.”

This is how “L&O: SVU” works. It doesn’t distance the viewer with theatrical “breaking the fourth wall” tricks. It distances the viewer by providing such an excess of information, which is never understood by the characters to be so, that the “Duh” response of any normal person is triggered several times an episode. This makes it possible to actually enjoy tales of horror that would otherwise be far too disturbing.

Whether the fears are international terrorist threats or the psychopath next door, “cartoon drama” helps you put them in a box and cope. You can read the whole thing here.

Story Collider at Oberon tonight (and my own science story)

Story Collider has a show at the Oberon tonight at 8pm, on the theme of “Survival of the Species.” Story Collider is one of those “paratheatrical science events” I’ve talked about, and it’s a good one. From their website:

Science surrounds us. Even when we don’t notice it, science touches almost every part of our lives. At the Story Collider, we believe that everyone has a story about science—a story about how science made a difference, affected them, or changed them on a personal and emotional level. We find those stories and share them in live shows and on our podcast. Sometimes, it’s even funny.

Tickets to tonight’s show are only $12–$10 for standing room–and you can drink, and meet interesting people, and walk around Harvard Square before or afterward. What are you waiting for?

I did a Story Collider last year, and I hope it was funny. It was about two baby rabbits that I raised as a child, and what I learned from them. Here’s the podcast–it’s about nine minutes long. The theme of the show I was in was “It Takes Guts.”

And a transcript:

Nine years old, and the next-door neighbor comes over with a big cardboard box. In the box, hasty handfuls of freshly mown grass. In the grass, two baby rabbits, the size of mice.

Do I want them, he says. He found them in his lawn, and picked them up before he thought twice, and now feared the mother would reject them. Did I want to try my hand at raising them.

Do you not understand that I am a nine-year-old girl? Some part of me wondered, as the rest of me shrieked agreement in a pitch so high a dog began barking across the street. Of course I want the bunnies!

My mother was ready to sue the guy. A Depression-era baby from Queens, she was like some deeply religious primitive who looks at animals with no grasp of their differences in locomotion or dietary requirements, only of their ritual cleanliness or uncleanliness. There were the horses in Central Park, which were Nice, and there were all other animals, which were Not Nice. Intellectually, she was capable of recognizing differences in species, but emotionally, every animal was either Horse or a Cockroach to her.

She was furious at the notion of Not Nice animals in her clean house, but the love of a nine-year-old-girl for small baby animals is a love that burns too bright to be denied. So she got her revenge another way, by explaining in graphic detail exactly why our neighbor had picked them up in the first place, and the connection between the unusually small size of the litter and the presence of that freshly mown grass in their box. The horror! Oh, the rabbinity!

Guts.

Which, on the metaphorical level, one of my little rabbits had to a far greater extent than the other. And this was where a psychologist was born. I would put my hand in the box—one would crawl in and explore, the other would race in panicky circles. One was tame and calm, the fat bunny Buddha of his cardboard world, happy to be petted, to eat bits of apple right off my fingertips. The other one treated me like I was a war criminal. My footsteps signaled terror. The day I took the box to a vacant lot and tipped it over, one dashed for cover—the other lingered, unwilling to leave.

Two rabbits. The same litter. The same rabbit upbringing, disrupted by the same nightmarish slaughter, the same miraculous rescue. And they were so tiny! Their little brains smaller than pencil erasers.

Somehow everything I had ever noticed about how the same song could make one person happy and another person sad, or how the kids in the Oklahoma school were nice to me but when we moved to Kansas I got bullied, or how Sunday School teachers could sometimes draw opposite conclusions from the same Bible story, crystallized around those rabbits and their impossible, irreducible difference.

Two years later, I read Watership Down, Richard Adams’ saga of a band of brave, bonny, British bunnies escaping existential threat for a better life. I cried for a week. (My mother was like, “Honey, it’s just a book. About cockroaches.”) I took to imagining the adventures my own foster rabbits’ adventure in Watership Down style, and it occurred to me that if those rabbits could tell their own stories, what very different versions they’d tell. Were their happy early days the source of a sustaining faith, or a childish illusion to be ripped away? Were the mysterious giants benevolent rescuers or only more subtle tormentors? Did the tipping over of that box into that field represent long-dreamed-of freedom, or expulsion into a savage and chaotic wilderness?

Personality is story. The story of a glass half empty or half full, if nothing else.

A friend of mine is a developmental biologist who works with all kinds of small lab-able animals, from mice to fruit flies. I asked her once how simple an organism could be and still have anything akin to personality.

She said she had worked with flatworms that can do one of two things with their lives: plank on the bottom of the beaker, or hug themselves against the side of the beaker. This is the big existential choice you face as a flatworm; being a career counselor for flatworms gets boring fast. Cut a flatworm in half, each half will regenerate into a whole, equally traumatized flatworm, identical to the original. And frequently, one half will be a side-hugger, the other, a bottom-planker. Planaria personality! Flatworm flair!

We once thought that humans were the only animals who used tools. No. Who made tools. Not that either. Who possessed language, an artistic instinct, morality—one by one, we are nudged from our exclusive pedestals. But still, still, we are the only species that tells stories. Homo narrativus. Who express that willful nubbin of self we call “personality” through planking plot, side-hugging symbolism. Tell me your stories, and I’ll tell you who you are.

My own stories have always been those of wanderers, of the ones born in the wrong place who must seek a new home. And the day came that like Hazel and Bigwig and Fiver from Watership Down, I too began to sense that the place where I lived (Missouri) threatened my well-being. So like those brave and bonny bunnies, I too set out for a better place: Boston. Where I would become a psychologist who studied the science of stories. And that is my story of science.

September 21, 2014

Sunday column: Being the grownup

Today’s column is online here, and both questions have a similar theme–knowing when you’re the grownup, the person in charge, the buckstopper. Knowing when it’s on you to set the tone. In the first question, two young couples seem to have developed a pattern where the slightly older couple plays host more often, and more comprehensively, than they would like. They need to back off and create some space for their younger friends to step up:

From the gentle condescension of your description (“only boyfriend and girlfriend,” and so on) it sounds as though your differences, though minor, have created a psychological rift, with you and your wife building your fortress as the wise, established couple on one side and your friends as the junior proteges who goof and frolic and provide occasional comic relief on the other. It’s entirely possible that all four of you are a bit tired of that dynamic. Moving to a more equal footing doesn’t require some dreadfully awkward Relationship Talk, fortunately. But if you and the missus want your friends to unlearn the habit of relying on you to provide space, food, and labor, then you will need to learn the habit of asking them to pitch in.

The second question was one of those Rorschach questions: “Should my son’s girlfriend who’s in town call me or should I call her?” Quick, what’s your impression of the Letter Writer? How do you envision the girlfriend? There, that just told you more about yourself than a dozen “Which Great House in Westeros Would You Belong to?” quizzes. I answered it as objectively as I could, but I’m sure my own unconscious biases came into play.

September 19, 2014

“Emilie” and the theater of science

“Emilie: La Marquise du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight” at Central Square Theater gets at the heart of the science/theater conundrum better than any play I’ve seen so far.

I was on the board of Underground Railway Theatre (one of the two companies operating out of Central Square Theater) and we struggled, sometimes, with what a play about science is, and what audiences are expecting and will accept. “Emilie”–sorry, that full title is a freaking albatross and I don’t know what the playwright or her initial producers were thinking–is in many ways a classic “science play,” that is, the biography of a particular scientist. In this case, Emilie du Chatelet, a French mathematician and physicist who was the mistress of Voltaire, among others. Emilie was one of life’s great winners, an energetic woman whose social rank allowed her a vast amount of privilege and the ability to spend her time as she would.

“Having it all,” Enlightenment style. (Lee Mikeska Gardner and Steven Barkhimer. Photo by A.R. Sinclair Photography)

What excited me about the play, though, was the underlying theme of the relationship–the correct relationship–between science and theater. Emilie is a scientist, and her lover Voltaire a playwright, and theater and hard science are frequently compared by her, during their arguments, to the disadvantage of theater. Science is about finding out the truth, Emilie implies, while drama is about creating what you want to see. Playwrights invent, actors lie, but scientists discover.

Except scientists have to do more than discover, don’t they?

Without the demonstration, no one else can understand the discovery. If no one else understands the discovery, it doesn’t become part of the canon. If it doesn’t become part of the canon, it doesn’t help guide other people’s discoveries.

Discovery without demonstration is a solo epiphany.

Discovery with demonstration is science.

Science needs theater.

If “Emilie” has anything as simple as a moral, it is that uncovered truth must be transmitted–demonstrated–to other people in order to reach its full worth. Emilie comes to realize that drama and science, like love and philosophy, are not opposed, but are necessary complements.

We put on the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony the day after I saw “Emilie,” and that is all about the theater of science, although our demonstrations of prize-winning articles and inventions are usually called off at the last minute by our onstage V-Chip Monitor. This year, the Medicine Prize went to Ian Humphreys, Sonal Saraiya, Walter Belenky and James Dworkin, for treating “uncontrollable” nosebleeds, using the method of nasal-packing-with-strips-of-cured-pork. Here is our distinguished Major Domo, Gary Dryfoos, gamely stuffing bacon up his nose by way of demonstration. Science isn’t always as sexy as Emilie.

September 18, 2014

Thinky links

The Ig Nobels (which are today! watch them online!) and my ongoing cold have kept me from reacting much, but I’ve been reading a lot great stuff!

The New York Times uses Randall Monroe’s xkcd to anchor a piece about the rise of geek/nerd culture: “[O]nce-fringe, nerd-friendly obsessions like gadgets, comic books and fire-breathing dragons are increasingly everyone’s obsessions.” UPDATE: Seven more pundits weigh in on the question “So what does it mean when geek culture becomes mainstream?” as a Room for Debate feature.

The NYT also summarizes recent research on how reading Harry Potter can affect young people’s political opinions.

There’s been a lot of good writing about science fiction and politics this week. The phrase “science theater” or “science entertainment” makes people think of stories about the hard sciences, but there’s a lot of implicit sociology and psychology in all stories, and it’s best to get it right.

i09 has a simply brilliant piece about how real-life revolutions work, and how history shows up the overly simplistic dystopias so popular at the moment.

Slate takes on a similar theme–the lack of any kind of real political backstory or worldbuilding in much science fiction. “”Like Snowpiercer, these stories of unchecked economic inequality aren’t finally sure if they want to be taken literally or figuratively. More often than not, they split the difference.

Another article in the same Slate series urges writers to envision better utopias.

This year’s Ig Nobel opera features a microbe chorus–and me, as assistant director pressed into service at the last minute. Thus attuned to microbes in the public eye, I was delighted by this 6 1/2 minute animation celebrating “invisible life,” and the Dutchman who first discovered it. Meanwhile, the Globe gently demolishes a much-quoted microbial statistic, and ponders its staying power:

Ten parts microbe and one part man vividly captures our imagination. Even if the estimate is off, it is innocuous—certainly it has no obvious negative consequences, nor is it a result of outright deception in the sciences, as in the case of debunked research connecting vaccines and autism. Perhaps the crude estimate endures because it serves the practical purpose of astonishing those who hear it, in the same way that bogus Martian canals inspired a greater curiosity about the solar system, or the myth that all humans only access 10 percent of their brains might foster a greater appreciation for neuroscience.

Finally, tickets have been selling fast for BAHFest–the Festival of Bad Ad Hoc Hypotheses–so get yours now! BAHFest is a contest for the most ingenious and hilarious evolutionary explanations for … well, pretty much anything. I was a judge last year and will be again.

They’ve gotten a fair amount of publicity in the past week for last year’s winner, who hypothesized that paleolithic warriors wore babies into battle. (The crying provides an adrenaline boost.) Here’s the winning presentation.

And, yeah, at least one person has taken it seriously. Oy. I do really enjoy BAHFest, but doing satire these days is a dangerous thing.

September 16, 2014

Recent notes (what I’ve read & seen)

My most recent culture-vulturing:

“Closer Than Ever” at New Rep. “Songs by Maltby & Shire” translates to “ballads for the middle-aged and middle-class,” but the sometimes dated numbers are given heartfelt and witty treatment by this excellent cast. A cast which includes … Science-Entertainment Quotient: Surprisingly high for a musical! Local actor Brian Richard Robinson, one of the two men in the four-person cast, “is a graduate of Tufts University School of Medicine, and currently works at a Cambridge-based biotechnology company.” (I tried to talk to Dr. Robinson at the opening-night reception but he was busy being asked how he remembers all those lines, so I made myself scarce.) Also, one of the numbers–”The Bear, the Hamster, the Hamster, and the Mole,” about the advantages of reproduction without romance, was staged as a TED talk.

“Ravenous.” Ain’t no party like a Donner party, ’cause a Donner party don’t stop. Guy Pearce and Robert Carlyle are cannibals in the old West–one unwilling, one gleefully triumphant. More satirical than graphic, although definitely very creepy. Science-Entertainment Quotient: Idiosyncratic. The Ig Nobel opera this year, “What’s Eating You?” is all about the food chain and, on some level, the idea that wisdom resides in accepting the fact that we must all eat and be eaten. I watched “Ravenous” after our rehearsal last weekend and found it relevant and inspiring … but clearly, this was me.

The Secret Place by Tana French. The hothouse atmosphere of an elite girls’ school and the 24-hour timeline (with flashbacks, of course), combine to make a claustrophobic psychological mystery. The portrayal of how young women police themselves and each other was especially compelling. Science-Entertainment Quotient: Nugatory, thanks to a credulous portrayal of teenage telekinesis which adds nothing to the plot or characterization.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. I’d last been there when I was eight, and yes, it was just as impressive to me today. And surprisingly redemptive. Like a lot of us, I’ve been reading and watching and thinking too much, much too much, lately, about humanity at its worst. The Smithsonians remind you of humanity at its best: curious, questing, ingenious. Science-Entertainment Quotient: Off the charts! The Hall of Human Origins was my favorite. Look at these gorgeous reconstructed faces of early humans!

Does the top right one look like Mandy Patinkin in “Homeland” to anyone else?

September 14, 2014

Sunday column: Medical TMI edition

Today’s column deals with medical TMI, or at least the Letter Writer’s perception of same. Medical TMI is definitely a thing–if you haven’t experienced it yet, kids, just wait until you, and more importantly your friends, are 40!–but one of the LW’s examples was a perfectly professional note from his veterinarian letting her clients know that she was undergoing cancer treatment, and the other two were passing strangers, and there is not much to be done about the discourse of passing strangers. By this guy’s rubric, I’m subjected to “sports TMI” every time I get on the T.

My own medical TMI is that I have some digestive problems that can occasionally make it hard for me to eat, and very, very easy for me to lose my appetite. So you’d best not be telling me details of your surgery over dinner. One of my good friends is a biologist and I don’t even let her talk about her job when we’re eating. (Gossip of grants and grad students is fine, but no details on the actual experiments, please.) But you can ask friends to indulge you.

I’m also coming down with a bit of a cold today, which I attribute to the weather change and the September Ingathering of thousands and thousands of new students and their germs. I get one this time every year. Since many of you probably do, as well, here’s the section of my book that deals with cold etiquette* for the office:

• Take visible precautions. When you’ve got a cold, take every precaution to avoid passing it on, and take these precautions somewhat ostentatiously, so that people know you’re looking out for them. Put on a little “security theater”: you want not only to spare people from getting your cold, you want to spare them the worry that they are going to get your cold. So wash your hands longer and more thoroughly in the bathroom than you normally do. Don’t leave used tissues on your desk, even if you used them only to wipe up a bit of spilled tea. Carry a small bottle of Purell with you and disinfect shared office equipment after handling it. Spray your phone with Lysol and keep the can out where others can see it. Don’t partake of shared food or ask to borrow anyone’s stapler. Toll a bell before you as you approach the cubicles of the untainted and scatter ashes on your head. (Well, perhaps not that.) And don’t ever feel embarrassed saying, “I have a cold, so I can’t shake hands” when introduced to someone. This is a courtesy that people truly appreciate. The warmest, most sincere hug in the world doesn’t convey quite as much care and consideration for others as refusing to touch them when you’re germy.

• Apologize in advance. If your cold is noisy—or if you have hay fever—send around an e-mail to your colleagues letting them know that you appreciate their patience until the hacking and schnortling subsides. People are generally willing to be awfully patient and good-natured as long as they feel they’re being recognized for being patient and good-natured, and that whoever is inconveniencing them knows that they are being inconvenienced.

• Provide a bit of information—as much as you feel is necessary and are comfortable with. Even when your illness or injury doesn’t affect others, it’s still a good idea to let people know what’s going on if you are visibly or audibly sick or injured. You don’t have to give everyone the full rundown of every highlight of the camping trip that left you with that nasty case of poison ivy, and exactly how much of your body it’s covering, and what exactly you were doing with that cute wilderness guide that led you to get it there. A simple, “Do I look disgusting or what? At least the next time I go on a wilderness excursion I’ll know how to identify poison ivy!” sufficiently acknowledges the scabby, oozing elephant in the room and makes others feel more comfortable.

It’s not as though coworkers or other PTA members aren’t noticing your rash or cast, even if they’re too polite to say anything. Take control of your own information and set yourself, and everyone else, at ease. (This benefits you, too. People are staring when you’re not looking and gossiping when you’re not listening, but they’ll do so less if you acknowledge whatever’s wrong.) This is especially important for women who are injured in such a way that it looks as though they might have been the victims of domestic violence. It can be very upsetting for coworkers or casual acquaintances to fear for your safety and well-being and not know if they should stage some sort of intervention.

*Etiquette for when you have a cold, not, like, Yankee as opposed to Southern etiquette.

September 11, 2014

So, my husband wrote a book

Mr. Improbable, aka Marc Abrahams, has not one but two bouncing baby books to brag about–This Is Improbable, Too, a collection of Marc’s essays and columns from the Guardian (exploring such questions as why it is so impossible to estimate the number of stupid people in circulation and who is the Einstein of pork carcasses), and The Ig Nobel Prize Cookbook, a “science humor cookbook filled with delicious and other recipes invented, inherited, devised, and/or improvised by winners of the Ig Nobel Prize, Nobel laureates, and organizers of the Ig Nobel Ceremony.”

Speaking of the Ig Nobel Prizes, they’re next Thursday, and sold out, but you can watch them online. Here’s a promo!

You can also join us at the Informal Lectures on Saturday, September 20 at 1pm at MIT Building 26, room 100. Come early, it’s free and always jammed. (If you like strange science and/or strange people, the Informal Lectures are even more fun than the ceremony proper, since the speakers get five whole minutes to explain what they did, and audience members can ask them questions.)

And because that’s not enough, he’s also doing a talk at TEDMED in Washington, D.C., this week. I’m joining him there, so posting may be light for the rest of the week.

September 9, 2014

If you were a meat puppet, could anyone tell?

If an alien took over your body and controlled your speech and actions, how long would it be before anyone noticed?

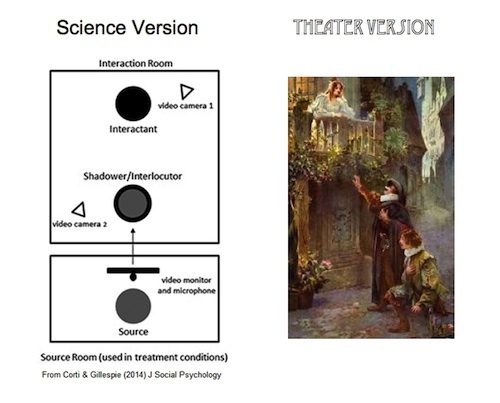

That’s not exactly the research question that “cyranoids” are designed to answer, but they could. Neuroskeptic reports that a couple of British psychologists, Kevin Corti and Alex Gillespie, have replicated two “cyranoid” experiments originally done by Stanley Milgram, of obedience-experiment fame.

“Cyranoid” was Milgram’s coinage–from Cyrano de Bergerac–for a person who is not speaking for or as themselves, but merely repeating words that another person is giving them. Cyrano had to hide in bushes and whisper loudly enough to be heard by Christian–and the audience–but quietly enough to be unnoticed by the fortunately rather dim Roxanne. This is all much easier with modern technology, and Corti & Gillespie were able to set up a microphone-and-monitor system that allowed Person #3 (Cyrano) to listen in on a conversation between Persons #1 and #2 (Roxanne and Christian) and feed “lines,” appropriate or inappropriate, to Christian.

Different aesthetic, same idea.

People didn’t notice, not even when Christian was a 12-year-old boy with his conversation being supplied by a 37-year-old psychologist as Cyrano. Maybe Roxanne wasn’t so dim after all.

Neuroskeptic calls this “Milgram’s creepiest experiment” and writes

If I started shadowing someone else’s speech, would my friends and family notice? I would like to think so. Most of us would like to think so. But how easy would it be? Do we really listen to each others’ words, after all, or do we just assume that because person X is speaking, they must be saying the kind of thing that person X likes to say? We’re getting into some uncomfortable territory here.

I’m not sure that much surprise is warranted, although I envy Neuroskeptic’s easy confidence that his loved ones are truly listening to him. We know people often attend more to the form than the content of other people’s speech–this is why Miss Conduct often recommends giving “placebic excuses” when ruffled feathers need to be soothed. And there’s a whole series of experiments showing that people don’t notice change in their environment. (I don’t mean “How could you not notice I changed the shelf liners, honey,” either–I mean like you’re talking to a whole ‘nother person than you started talking to, and you still don’t notice.)

More to the point, though, people aren’t going to twig to a cyranoid because cyranoids don’t exist. As Corti & Gillespie write,

It seems that when encountering an interlocutor face-to-face, people rarely question whether the “mind” and the “body” of a person are indeed unified–and for good reason, as social interaction would be undermined if we began to doubt whether each person we encountered was indeed the true author of the words they expressed.

The authors point out that people do often notice identity discrepancies “in artificial environments (e.g., Second Life and other virtual community games) wherein users can construct outer personae which starkly contrast with their real-world identities.” You don’t even need to go into immersive environments–even the comment threads on opinion blogs will tend to feature people accusing others of not really being a member of whatever group they’re attempting to speak for, or of adopting a sock-puppet identity, or the like. When we know that people’s words and being need not match up, we can be quite vigilant about clues.

I always figured that’s how Starfleet crew members managed to cotton on so quickly whenever their colleagues got possessed by the Aliens of the Week. Deanna Troi learned all the Signs of Alien Possession to watch out for when she was in psychology school, just like nowadays you learn the signs of addiction or suicide risk. I don’t even want to think how long it would take me to notice if my boss got assimilated by the Borg.

Corti & Gillespie write that people have always been fascinated by the idea of persons speaking through other persons, or different identities in the same body:

This well-known story [of Cyrano de Bergerac] is but one of the many examples of a fantasy that has appeared in the arts and mythology throughout history–that of the fusion of separate bodies and minds. Other illustrations include The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, in part the tale of a fraudster who is able to attain great power by presenting himself to the world through an intimidating artificial visage. The film Big entertains the folly that ensues when an adolescent boy awakens to find himself in the body of a middle-aged man. More recently, films such as Avatar and Surrogates have imagined hypothetical futures in which mind can be operationally detached from body, allowing individuals to operate outer personae constructed to suit their social goals. Fiction though they may be, these stories illuminate the power façade has over how we are perceived by ourselves and by others, and how we and others in turn behave in accordance with these perceptions.

Robin Abrahams's Blog