David duChemin's Blog, page 27

April 23, 2014

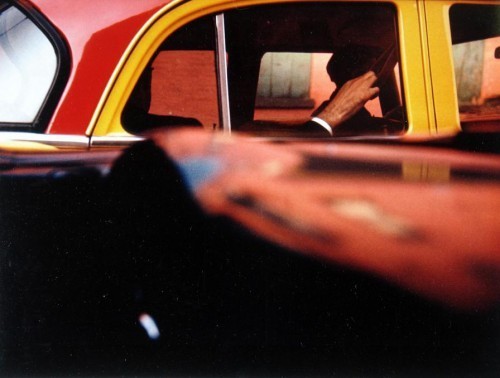

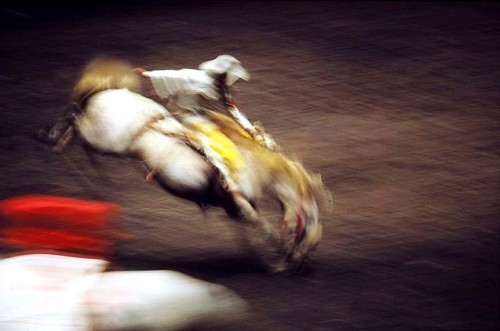

Study the Masters: Ernst Haas

Born in 1921 in Austria, Ernst Haas (1921-1986), like Saul Leiter born two years later, became known for his early work with Kodachrome. His photography was strongly graphic, emphasizing colour as a compositional elements and often using motion and reflections. Haas was a member of Magnum and a colleague of contemporaries Robert Capa and Henri Cartier Bresson.

You can see his work and find out more on the website of the Ernst Haas Estate. Take some time to look through his work. Study the composition. Then poke around the website, Philosophy By Haas is a particularly good read, as are the Reflections on Haas.

If you can find them, Haas wrote 4 books, all of them now out of print: The Creation (1971), In America (1975), In Germany (1976), and Himalayan Pilgrimage (1978). Posthumously, his work is in Ernst Haas, Color Photography (1989), Ernst Haas in Black and White (1992), and Color Correction (2011).

“There is only you and your camera. The limitations in your photography are in yourself, for what we see is what we are.”

“I am not interested in shooting new things – I am interested to see things new.”

“You don’t take pictures; the good ones happen to you.”

April 21, 2014

Personal Projects

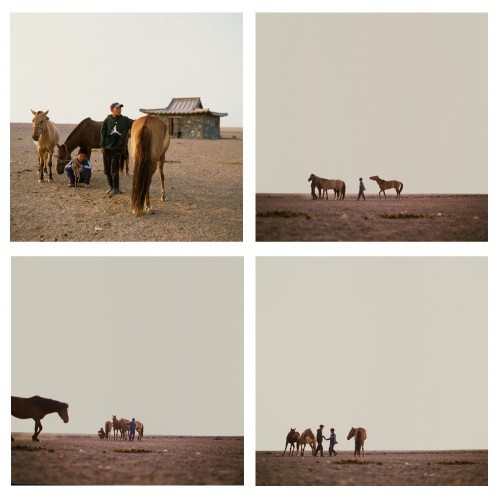

Mongolia series. 2012. Hasselblad and some old film.

Mongolia series. 2012. Hasselblad and some old film.

There’s a lot of talk among photographers about personal projects. I assume, by this, we mean projects that are not for clients, though I’ve tried very hard to never do a project that is not in some way also personal. Life’s too short. For me the key word isn’t “personal” because that’s assumed. If it’s not personal, don’t do it. No, for me the key word is “project.” The idea of a project is that it’s something specific, defined by constraints, and I believe very strongly in them. Personal projects lead to bodies of work. Personal projects provide a conduit for intentional creation. The alternative is an accidental, ad hoc approach to photography, an approach I also love but for most of us it’s a scattered approach that takes a lifetime of curating before it becomes something brilliant only in hindsight.

The personal project is about intent and curation, the opposite of most 365 projects. I’m not qualified to speak about 365 projects. Much as I love what I do, I don’t do well with a sense of obligation. I love constraints. I don’t like obligation. It’s probably a difference that’s only in my mind, but I’d rather focus on a theme or a final body of work (which I admit I could do on a 365 project…) than the need to make photographs daily. I’d rather focus on what I create than how often I do so.

But that’s not what I wanted to say. This is what I wanted to say. Last weekend someone asked me about personal projects on Facebook. She had a bunch of ideas and was a little stuck on which one to choose. So I chose for her and told her to start now. Talking about a project is not the same as doing a project. So at the risk of talking about personal projects, a couple thoughts.

1. Choose Something. Art, like life, is about choice. We almost always have more choices in front of us than the time to do them all. Pick one. Which one? I don’t know. But if you like the 6 choices in front of you enough to be indecisive, chose one and move forward. The others will still be there later if you come back to them. Flip a coin if you have to. Picking the “wrong one” and moving forward is better than picking nothing. Begin now.

2. Create Constraints. By this time next year I will have a body of work that is 24 images deep, only black and white, only on the theme of water. I will publish it as a print-on-demand book called Dark Water. That’s a well-defined project (but don’t wait to see it, it’s just an example.) What is the theme of the project? When will it be done? What are the deliverables?

3. Be Open. Sometimes the best thing about choosing a well-defined project is that it leads you to a better one. If you’re 2 months into the project and it starts taking you in a new direction, away from one of your constraints, see where it leads. The power of constraints is in giving you a strong starting point, not in keeping you from following the muse. Few projects I know end up exactly where the artist thought they were going when they started.

4. Ship It. Do your project as you like. For me the rule is: ship it. I always have a deliverable, even if it’s just for me. A printed folio. A book. Something more than a collection of images sitting in Lightroom. For me there’s something powerful about bringing my work into the physical world and putting my mark on it. Even if it’s only for me. Especially if it’s just for me.

Personal projects can give you direction and focus. I’d be lost without them and believe they make me a better photographer for having that focus. Make it well defined. Make it deliverable. But most importantly: make it something you care about – it’ll be part of your legacy – and make it now.

April 19, 2014

Composition & Questions

We often talk about composition as though its something that can be done right or done wrong. When you look at it in those terms photography is not about expression, but about following the rules. The best thing I ever learned on the photographic journey was this: there are no rules. None. Nope, not even the rule of thirds. No such thing.

We make compositional decisions for all kinds of reasons, but if “following the rules” or “doing it right” are among those reasons, the resulting images will be just like all the others. They can be sharp, free from chromatic aberration, and made with the best glass in the world, but totally lifeless. Forget right or wrong. Forget perfection. Thinking in terms of what you can do to make the image stronger, or more aligned with what feels good are more helpful guides, even if they feel a little vague.

So how do we learn to compose? That’s a good question. In fact, I think that’s the answer, right there: questions.

If what you long to do with your photography is more than mere technical proficiency, if you want to find your voice and express yourself, then questions will be more helpful to you than any list of tips, rules, or the parlour tricks we use in post to make up for weaknesses made in the camera.

Here are some of the questions I find rattling around in my own head while composing my photographs:

What do I think and feel about this scene? If you don’t have ideas about this, composing a photograph that speaks about these thoughts and feelings is going to be tough!

What must I include and how much can I exclude?

What devices can I use to exclude the unnecessary without diminishing the necessary? For example, should I use a longer lens to isolate my subject or keep the wide angle but move closer, perhaps shifting my position and changing the image’s perspective? There’s more than one way to skin a cat (but try not to let the neighbors see you doing it).

What are the relationships between the elements, and can a shift in my position (and change in perspective) make that relationship stronger?

Where are the lines in this photograph and would a change in framing (vertical or horizontal), aspect ratio (square frame, 16:9, etc), or lens make that stronger or weaker?

What is the light doing? Light contributes to composition, creating shadows, depth, and mood. Ignoring that shadow means missing a chance to allow it to make the image stronger.

What kind of moment is present? Timing is everything. Imagine there’s a kid running across the yard – some moments will be stronger than others – some showing his stride more clearly, others when there is nothing in the background behind him. The decisive moment is not just about which moment you choose, but about how that moment contributes to the geometry of the composition.

What is the relationship between the foreground and the background?

Is there depth in my image? Could there be more? Would it benefit from less? Changing lenses and perspective can deepen or flatten the scene.

Are there repeated elements in the scene that provide a visual echo or rhythm to the photograph? Could I pull out a little and include more of them, or tighten up a little and include fewer?

Do my lines lead the eye into the frame or out of the frame and could I change that to better direct the eye?

Are my chosen settings (aperture, shutter speed) going to change the look of certain elements, and do so in a way that helps me tell my story? For example, what elements will be less focused because of depth of field, or blurred because of a slower shutter. That blur or lack of focus will change the shape of things and change the way we compose the image.

It would be great if there were rules. So much easier just to not think about this stuff. But it’s the fact that we ask the questions, wrestle with them, and come up with different responses one day than we do another, that keeps us making photographs that are reflections of who we are, photographs that keep us interested and curious, and experiencing something more than just visual formulas and homogeny. It’s the questions that keep our photographs human.

A couple years ago I wrote PHOTOGRAPHICALLY SPEAKING as a way to to have this conversation with more people. If you’re looking to learn more about what we say with photographs and how we say it (isn’t that what composition is, afterall?), you can find that book on Amazon here. You should also read Michael Freeman’s excellent book, The Photographers Eye. You’ll never lean on the rules again.

Compostion & Questions

We often talk about composition as though its something that can be done right or done wrong. When you look at it in those terms photography is not about expression, but about following the rules. The best thing I ever learned on the photographic journey was this: there are no rules. None. Nope, not even the rule of thirds. No such thing.

We make compositional decisions for all kinds of reasons, but if “following the rules” or “doing it right” are among those reasons, the resulting images will be just like all the others. They can be sharp, free from chromatic aberration, and made with the best glass in the world, but totally lifeless. Forget right or wrong. Forget perfection. Thinking in terms of what you can do to make the image stronger, or more aligned with what feels good are more helpful guides, even if they feel a little vague.

So how do we learn to compose? That’s a good question. In fact, I think that’s the answer, right there: questions.

If what you long to do with your photography is more than mere technical proficiency, if you want to find your voice and express yourself, then questions will be more helpful to you than any list of tips, rules, or the parlour tricks we use in post to make up for weaknesses made in the camera.

Here are some of the questions I find rattling around in my own head while composing my photographs:

What do I think and feel about this scene? If you don’t have ideas about this, composing a photograph that speaks about these thoughts and feelings is going to be tough!

What must I include and how much can I exclude?

What devices can I use to exclude the unnecessary without diminishing the necessary? For example, should I use a longer lens to isolate my subject or keep the wide angle but move closer, perhaps shifting my position and changing the image’s perspective? There’s more than one way to skin a cat (but try not to let the neighbors see you doing it).

What are the relationships between the elements, and can a shift in my position (and change in perspective) make that relationship stronger?

Where are the lines in this photograph and would a change in framing (vertical or horizontal), aspect ratio (square frame, 16:9, etc), or lens make that stronger or weaker?

What is the light doing? Light contributes to composition, creating shadows, depth, and mood. Ignoring that shadow means missing a chance to allow it to make the image stronger.

What kind of moment is present? Timing is everything. Imagine there’s a kid running across the yard – some moments will be stronger than others – some showing his stride more clearly, others when there is nothing in the background behind him. The decisive moment is not just about which moment you choose, but about how that moment contributes to the geometry of the composition.

What is the relationship between the foreground and the background?

Is there depth in my image? Could there be more? Would it benefit from less? Changing lenses and perspective can deepen or flatten the scene.

Are there repeated elements in the scene that provide a visual echo or rhythm to the photograph? Could I pull out a little and include more of them, or tighten up a little and include fewer?

Do my lines lead the eye into the frame or out of the frame and could I change that to better direct the eye?

Are my chosen settings (aperture, shutter speed) going to change the look of certain elements, and do so in a way that helps me tell my story? For example, what elements will be less focused because of depth of field, or blurred because of a slower shutter. That blur or lack of focus will change the shape of things and change the way we compose the image.

It would be great if there were rules. So much easier just to not think about this stuff. But it’s the fact that we ask the questions, wrestle with them, and come up with different responses one day than we do another, that keeps us making photographs that are reflections of who we are, photographs that keep us interested and curious, and experiencing something more than just visual formulas and homogeny. It’s the questions that keep our photographs human.

A couple years ago I wrote PHOTOGRAPHICALLY SPEAKING as a way to to have this conversation with more people. If you’re looking to learn more about what we say with photographs and how we say it (isn’t that what composition is, afterall?), you can find that book on Amazon here. You should also read Michael Freeman’s excellent book, The Photographers Eye. You’ll never lean on the rules again.

April 16, 2014

Study The Masters: Saul Leiter

I’m starting a new series called Study the Masters. Short and sweet, it’s my chance to put you on to photographers from the past that have made our art what it is. Hands down, the best photographic education, once you know how to use a camera, is to study the work of others. This is my way of suggesting who some of those others might be.

This week it’s Saul Leiter (1923-2013), a New York photographer who left us this past November. Saul was an eccentric artist who photographed and painted in the same neighborhoods in New York all his life. I love Saul’s use of colour and negative space, especially his selective focus, and his use of reflections is wonderful. I could look at his work for hours.

“I admired a tremendous number of photographers, but for some reason I arrived at a point of view of my own.”

“If I’d only known which [photographs] would be very good and liked, I wouldn’t have had to do all the thousands of others.”

You can see some of his work immediately with a simple Google Image search.

There’s a movie about Saul, a documentary made in the last couple years of his life, coming out just now called In No Great Hurry, and if you get a chance to see it you should.

I highly recommend this book about Saul Leiter and his work. It’s on my coffee table right now and it’s one of the best photography books I’ve bought in a while. Saul Leiter, by Vince Aletti. (Amazon link). If you can get it, or have the budget, a copy of Saul’s Early Colour, would be a treasure. Hard to find.

“Seeing is a neglected enterprise.”

April 14, 2014

The Visual Imagination

A couple years ago I sat in a wheelchair in front of a painting, a piece from one of Canada’s Group of Seven, a landscape from the northern shore of Lake Superior. I could feel the temperature of the wind on my skin, I could recall the acidic smell of soil rich with pine needles, even feel the sun on my face. It was a turning point for me. I left wondering what I could do to create that kind of experience in my own photographs. That was the start of a journey I’m still enjoying, and a renewal of some of my passion for creative photographic expression that’s unbound by the need for perfection but driven by a desire to more deeply feel my work.

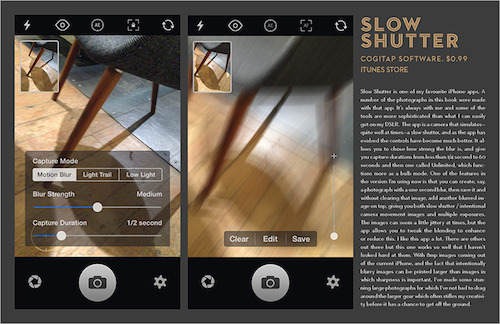

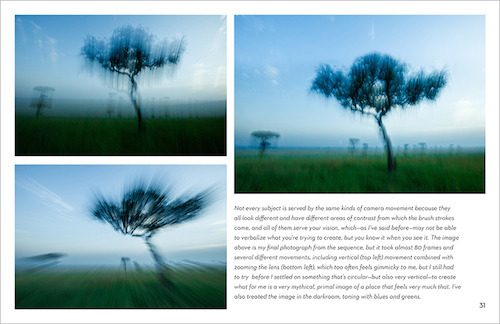

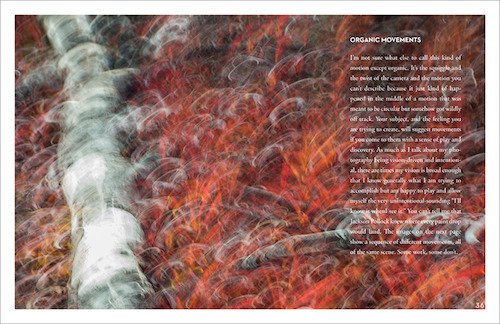

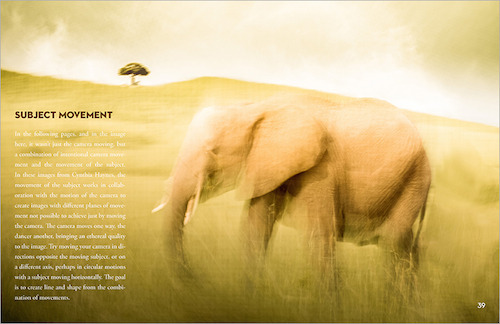

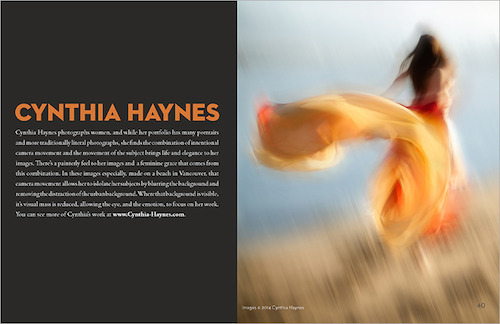

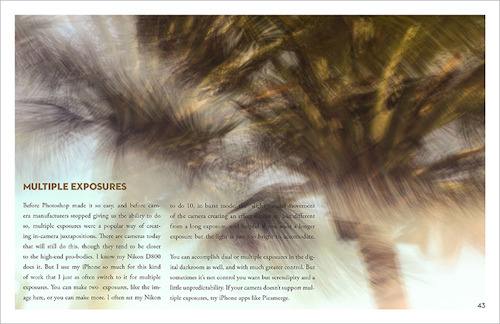

Our cameras do amazing things, but since the beginnings of this craft, we’ve leaned heavily towards illustrative and literal interpretations of the world around us. Our cameras are capable of so much more, and freed from the need to be so literal, they can create photographs that are beautifully expressive. The Visual Imagination, Ideas & Techniques for Creative Photographic Expression is about that expression, and we’re releasing it today.

Whether you want to make abstract or impressionist photographs or just need a bit of a break, I wrote this eBook to help you explore the possibilities of the camera when we allow ourselves to slip out from under the thumb of the rules and the constraining ideals of so-called technical perfection. It wasn’t that long ago that painters freed themselves from a similar constraint and gave us the gift of Impressionism and the subsequent movements.

If you’re not sure this kind of thing is for you, this short article about three ways abstract and impressionist photography can make you a better photographer might help.

A downloadable PDF, published by Craft & Vision, The Visual Imagination is 65 spreads of techniques and ideas that explore intentional camera movement, subject movement, and abstraction through various means. Accompanied by case studies of photographers like John Paul Caponigro and others, that’ll inspire you to move past the so-called rules, I’m hoping this book gives you new freedom to express yourself – even if that’s through work that’s usually more literal – by understanding the tools of your craft as tools of creative possibility, not just technical instruments.

Save 25% – Purchase The Visual Imagination before 11:59PM (PST) on April 21/2014, using the discount code EXPRESS25 and it’s yours for only $7.50

April 10, 2014

Impressions & Abstracts

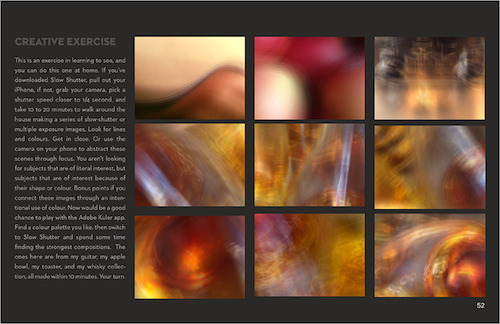

Next week we’re releasing my next eBook - The Visual Imagination, a book about creative techniques and ideas that focuses mostly on impressionism and abstraction. Yesterday I was doing a pre-release podcast interviews, talking to Ibarionex Perello, the amazing voice and mind of The Candid Frame, and he asked me the one question I’m so fond of asking others. Why?

Not everyone does photographic work that willingly abandons the literal, so why play with ideas of abstraction and impressionism at all?

1. Focus on Experience

This new book, The Visual Imagination came out of an experience I’ll tell you about on Monday. The short version: I had an experience with a painting – to say I merely looked at it wouldn’t do the moment justice – that made me wonder whether my own work created a similar experience in others, and if not – which is what I suspected – why not, and was there a way I could do that? Whether we create literal photographs or something more abstract, I think many of us are more hung up on creating something that can be understood. Understanding is good, but it’s not everything. There is a lot of music and visual art that moves me, creates in me an experience that’s more than just rational – and sometimes not rational at all – that I don’t understand. There’s poetry I don’t understand but it speaks to me. I want my photographs to do that. Learning to photograph in a way that’s not what I normally do has taught me to focus more on the experience, on things like mood and colour, than I once did.

2. Learning to See

When we zoom in so close on a flower that we reduce it to form and colour and nothing recognizable, we learn to see that scene for the form and colour, not the flower. The more we experiment with alternate ways of seeing, the more able we become to see the building blocks of great photographs – line, shape, balance, tension, colour, visual mass. The job of the photographer is not merely to use the camera in her hands but to perceive, to truly see what’s there.

3. Play is not practice

Remember how we used to spend hours as kids playing in the back fields and back alleys? That play taught us better and deeper than most classroom lessons. Practice is good, but it often focuses on the right way to do things, and avoiding the wrong way, and too much focus on avoiding the wrong way to do something stifles creativity in a field where there really is no absolute wrong. There are principles in photography but no rules and the more we engage in play, the more creativity we’ll discover and – this is for those of us who lean towards the geeky stuff – the better we become with our technical tools. You may never put a photograph with intentional motion blur into your portfolio, but playing with the techniques will make you more creative and technically proficient.

I can’t wait to introduce this book to you, but with or without it, I encourage you to jump the creative ruts, find something that gives you that sense of play back, and helps you focus on creating unforgettable visual experiences for you and the ones who view your work.

April 9, 2014

Choose Your Risk: A RePost

I wrote this post three years ago this month (April 20). A couple days later I fell off the wall in Pisa that so changed my life. Don’t think I don’t appreciate the irony of the timing. Seemed a good candidate for a repost from the archives. Funny how it all plays out…

Last year I decided to make a change in my life. I bought a truck, sold my stuff, gave up my condo and a fixed address and set out on an adventure that’s still barely two months old. My plan was to spend the rest of 2011 traveling North America when I wasn’t photographing or teaching internationally elsewhere. And then I started the journey itself and things began to change. I began to like this lifestyle more than I thought. I miss having a home less than I expected. I had more time with people than I imagined. I found myself settling into the rhythms of nomadism and I started to dream bigger and allow myself a few more “What Ifs”

And then my buddy Zack Arias hosted a meet-up event at his studio in Atlanta and that night was magical for me. I met some amazing people, including Zack, face to face for the first time. And Zack, if you don’t know him, is the kind of guy with no shortage of opinions on things. One of those opinions that evening was that I should speak to the group, and say “something inspiring” or something. I declined. He insisted and told me that “in one beer, you’re on!” I figured I could make my beer last all evening and avoid speaking entirely, until he made it clear I was on when his beer was done, not mine, and I got the feeling that wasn’t going to take long.

Not sure what to say, I told the story of the last few months and the growing awareness of the brevity of life that had led me here. And the more I talked (a barely coherent mix of spontaneous babbling and preaching) the more it galvanized something in my own mind; a feeling that I’d passed a point of no return. I have written before that life is short, but it’s becoming more than a passing feel-good idea; it’s becoming the place from which I make my biggest decisions. I am moved more than ever by the awareness of the brevity of life and that the fulfillment of our dreams and longings aren’t simply things that accidentally happen to us. Life is complicated and at times feels more like something that happens to us than something we make happen, I know, but people live extraordinary lives because they overcome those circumstances and choose to do the things they dream about.

But too many people don’t listen to their dreams at all. Or they listen but allow the dreams themselves to get drowned out by the desire to fill their homes with stuff or even just to play it safe, or – and this is more likely – they listen to their fears.

The culture we live in would rather watch great stories on movie screens than live them. Why? I think it’s fear of risk. The bigger the risk the greater the potential reward but also the greater the potential for “Oh God, Oh God, we’re all going to die!” or something similar. Fear is the loudest voice in many of our lives. Fear of rejection leads us to buy some crazy stuff, as well as keep our voice down when it should be loudly telling others “I love you.” Fear of the unknown keeps us close to home. Fear of fear keeps us in therapy. So we’d rather watch Braveheart and imagine ourselves with that kind of courage than risk finding out for ourselves if we have it. Makes sense. Afterall, Braveheart gets horribly disemboweled at the end. But while our hearts swell with resonance as William Wallace says “All men die but not all men really live,” we wash it away with popcorn and sodas and go back to sleep. That very quote, or the sentiment it reflects, points to two things for me, and these two things make it easier to listen to something other than the fear.

1. All we have is now. I’ve said it before: none of us lives forever. The time to make a change is now. You may not be able to pack the house and go on an adventure right now, but you can put yourself on a path to doing it. Don’t wait until you’re 65 and retired. You might not be around or in good health. The time is now. Don’t be the one breathing his last breath wishing he’d gotten around to the things that were most important. Live with all the passion and energy you’ve got now. Now is all you have. Each moment matters.

2. Risk is inevitable. We all risk, day in and day out. You fall in love at first sight with someone amazing and you’ve two choices, both involving risk. You can act on it and risk rejection, or you can sit on it, do nothing, and risk losing what might be the best thing you might ever experience. Sure, rejection’s painful (but not certain), but it’s nothing compared to the life-long regret of letting her slip away (absolutely certain). You have a dream and the only way to get at it is to make some changes, live sparsely, and pull your kids out of school for a year. You can do it, and risk failure (not as likely as it seems) or play it safe and let the dreams remain un-lived (absolutely certain).Life is about risk. The best stories hinge on it. But even those risks aren’t as big as they seem. It’s funny how we often prefer to listen to fears and avoid risks that are only potentially painful, and in so doing sacrifice our dreams – a loss that is most certainly painful.

It could be that the last thing you want to hear is another sermon. I get it. None of this stuff is easy. There were moments of nerves, and even overwhelming fear, as I was staging to give up so-called normal life. It’s taken some painful decisions and course-corrections over the last few years to get to this place. It’s taken falling down and getting back up. One day my diabetes may prevent me from pursuing these adventures. All the more reason to take a deep breath and do it now. I had planned to go back to Vancouver at the end of this year – it was the “sensible” decision. Instead I am looking into what it will take to come back to Europe and live nomadically here for a year – to spend time on the British Isles and Scandanavia before taking the boat to Iceland for the summer, then to drive to Istanbul or Marrakech or Ulaan Bator.

All those many words to say: don’t settle. Your dreams will be different than mine, but the regret for not living them will be the same. Life is short. Choose your risk intentionally, don’t try to avoid it. Live a great story; don’t settle for merely watching them. Whatever got stirred in you when I wrote the first blog post in the Life is Short category, I hope you’re moving towards it. Because those dreams are part of what it means to live life to the fullest.

April 5, 2014

3 Versions: Discuss.

I recorded a new episode of About the Image this afternoon. Episode 14. It’ll be online in a couple weeks, I think. But I wanted to post the images here. 3 different versions. If you want to play, here are a couple questions to consider:

How does the top image use shadows as a compositional tool?

What does the choice to leave the shadows free from details give us that a more detailed version, below, does not?

The second image, below, has much more detail in the shadow, popular these days among those who insist on this sort of thing. Is it stronger to you? Weaker? Why?

The third image is the same as the first, with a change in colour balance. How does that colour balance shift change how you read and experience the photograph?

There are no wrong answers, just a chance to exercise your visual language skills. Comments are open if you want to play.

If you enjoy this kind of discussion, you can get more on the free Craft & Vision video podcast here, and more still in Photographically Speaking (Amazon link), a book I wrote a couple years ago that is, I think, my strongest teaching on composition.

April 3, 2014

Find an Itch

Since writing VisionMongers, I talk to a lot of photographers every year about business stuff. The frustrations, fears, and struggles are all similar. No one said this would be easy. As I recall, and it’s been a while since I wrote the book, I spent time trying to convince people not to go down this path, so when they inevitably did they did so with eyes wide open. Anyways, back to the conversation with photographers that seems to be on repeat right now, and the reason for this article being called what it is.

It’s easy to forget that people don’t have a natural need to buy photography. They have a lot of needs and desires, often impossible to tell apart, and most of them don’t include you as a defacto starting point. If you want to make it as an entrepreneur whose commerce revolves around your photography, that photography has to meet a need. It has to scratch an itch.

Forget for a moment how important all the other stuff is – the logos and the business plans and blogs. If you miss this or forget it, you’ll never get off the ground: for whom are you creating value? Whose itch are you scratching? Who are you serving? People have problems they themselves can’t solve. You can. That is the core of every business transaction. The deeper that need, and the more uniquely you can meet it, the more value you offer. Remember that when you market yourself. Because no one, but no one, cares if you say you’re an award-winning photographer. That scratches your itch, not theirs. Remember it when you negotiate, because they aren’t doing you a favour by coming to you, they’re asking you to help. The more clear you make that itch, and the more clear you make your ability to scratch it in a way others don’t, the more value you put on the table. Remember it in everything you do, every blog post you write, every social media sound bite you create. Does it teach them? Inspire them? Make them laugh? Give them something? If it doesn’t, it’s just noise.

Combining art and commerce isn’t mysterious. Find an audience you can serve. Find an itch you can scratch. And then pour yourself, heart and soul, into serving that audience and scratching the hell out of that itch. The rest is details. Not easy details, I know. And there’s a world of work involved in the search for the right audience and an itch that you scratch like no one else. But once you find it, don’t get sidetracked. Serve. Scratch. Repeat.

The best two questions you can ask every day, in this regards, are these: who am I serving, and how can I serve them better? Even if you’re not in business, they aren’t bad questions, because how you answer them is how you bring value and relevance to what you do, even if no money changes hands.

I believe a living can be made doing what you love, that now is as good as – if not better than – any other time in history to do so, and that people complaining that things aren’t what they used to be are missing out on astonishing (challenging) opportunities in the present.

VisionMongers, Making a Life and Living in Photography, is available on Amazon and from other major booksellers,

and though I wrote it and therefore lack any objectivity, I still think it’s one of the most honest conversations available on the subject.