David duChemin's Blog, page 22

October 15, 2014

The Best Deal in Education Ever

[image error]Today is the first day of the 5 Day Deal, an idea I like so much I’ll be kicking myself for years for not thinking it up myself. Here’s the deal: a bunch of photographic educators -some of the best on the planet, like Gavin Gough, and Zack Arias - bundled some of their best products, over $2,000 worth of products to be exact, in a package that will cost you only $89. That’s 95% off, and it lasts only 5 days, then it disappears.

Only $89 for 300+ Lightroom presets, 70+ hours of video tutorials, 500+ professional textures, and a whole bunch of great eBooks. Just to be able to get Zack Arias’ 4-part video series OneLight 2.0 will be worth it! And Gavin Gough’s teaching on workflow is killer. And there’s over $100 worth of Craft & Vision products. Take a minute to look at the offering, it’s huge.

On top of this incredible deal, a really big chunk of change goes to four worthwhile charities – Flashes of Hope, Mercy Ships, Camp Smile-A-Mile, and Bethel. And if you get in on the 5 Day Deal through the links here on this blog (it’s an affiliate thing), we’re going to give an additional 10% of what we earn (above what Craft & Vision normally gives to The Boma Project) to two of my favourite projects, The BOMA Project, and The Kilgoris Project, both working in Kenya, and both doing exceptional grassroots work among the poorest of the poor, and people I know and love. I know we have a lot of sales, and there’s a ton of stuff out there to choose from when it comes to spending your money, but this is hands-down, the best deal you’re going to get in photographic education for a long, long time. Do me a favour and take a look, you won’t regret it.

Updated: We’re going to raise our donation to 20% – that’s 10% to each BOMA and Kilgoris. Thanks for being part of this!

October 10, 2014

Forget Jumping.

Here’s another Q&A from The Big Q. This time we’re talking about making the jump from full-time job to full-time photographer. If you’ve got questions you’d like answered, I’d love to help: leave them in the comments.

Q: When you first made your decision to become a full time adventurer/humanitarian photographer what scared you the most? Did you have a full time/regular job before that? How do you get the balls to make such a move? I have a full time office job with good pay, and I’m good at it, but I just don’t feel any connection with it. Instead, I think about photography everyday, every hour, and almost every minute. I have been planning my extraction strategy for a while but since I have a mortgage and family to support, I get butterflies in my stomach to just jump and make the move, even if it feels like this job is sucking the life out of me. ~ Luis

Luis, first, way to go for articulating this, and admitting both your desires and your fears. I think that’s the hard part: coming to grips with the need for change. Change is hard. Most of us get more than butterflies in our stomachs when it comes to change. Change promises uncertainty. So stop looking for it (the certainty). It’s not there. Adventure is there. Meaning is there. A great story is there, because story is all about change. That’s the first thing I need to tell you. Nothing I say will make this less exciting (read: terrifying).

You asked about my story. It was similar in some ways. I saw the need to change. The desire to do something different. Unlike you I had already been living off my creativity. I was a comedian for 12 years, and that’s not what I would call a regular job. But it was full time, and leaving it was still hard (see previous note about change.) But in some ways it was different. I had no family to support. There was, in some significant ways, less on the line for me. But it probably didn’t feel that way at the time. Change is change. Fear is fear.

But change doesn’t have to come with a jump, and I think that’s where people get stalled. Imagine you’re on a 30-foot cliff. You want to get into the water below. You could jump, and many of us do. We like the jump, in part because of the excitement. But that’s not the only option. Walk down the trail, one step at a time, and the water gets closer with each step. Sure, it’ll have it’s own challenges, but jumping is not one of them. So, what are you doing now to grow an audience, find clients, and bring your product/service to market? How are you spending your lunch breaks, or your evening time after the kids are in bed? How many clients do you have now? That’s your step-by-step. And you’ll put that extra money into the “one day I’m going to get in the water” account. And one day, free from the need to have jumped, you’ll wake up with too many clients to keep doing both the “real” job and the moonlighting gig. You’ll have money in the bank. You’ll have tested the waters a little with proven clients and some of the early mistakes out of the way without costing too much. And then you’ll dive in.

You asked what scared me the most and how I found the balls to do this? What scared me the most was not changing, not doing what I knew I needed to do. I had a great career in comedy but eventually it wasn’t meeting the needs and desires of my soul and I needed to change. I found the balls (ladies, forgive the weird, too-macho metaphor) the same way you will. Look down. They’ve been there all along. Change or don’t change. That’s up to you. But don’t be mistaken: it’s not the jumping for which you need your balls. That just takes legs and the will to change. And you can do that step by step as easily as you can jump. Forget jumping. That’s not the goal. The goal is getting into the water. Do that any way you can. That’s what takes balls. And you’ve already got them.

We’re going into Thanksgiving weekend here in Canada – have a wonderful week with those for whom you’re thankful. We’re still driving home to Vancouver. Today we hit the 19,000Km mark on this roadtrip – it’ll feel so good to finally get home in 3 or 4 days! Happy Thanksgiving, friends.

October 7, 2014

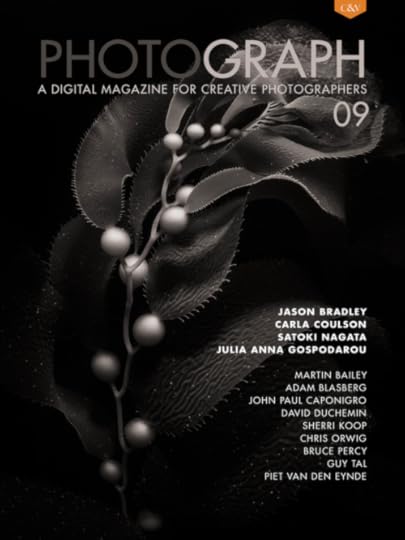

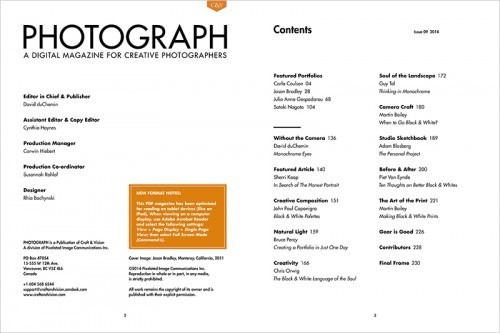

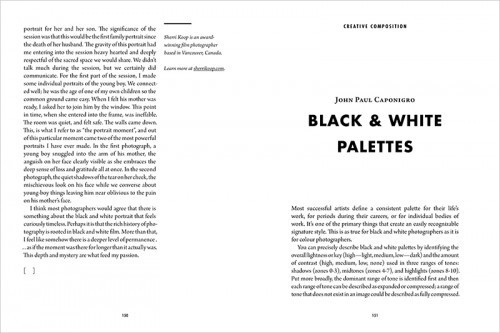

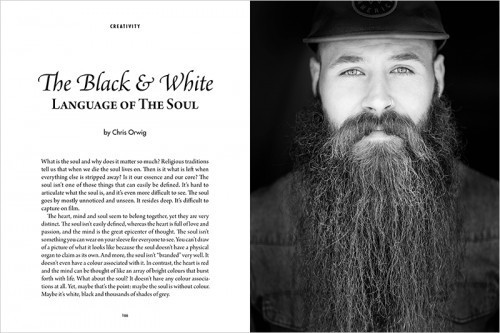

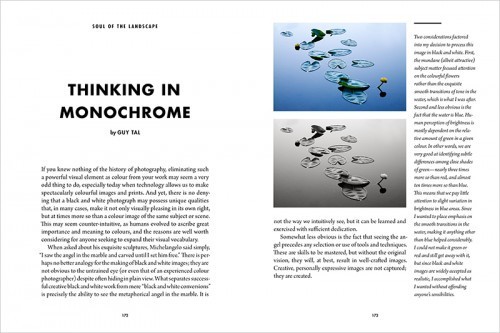

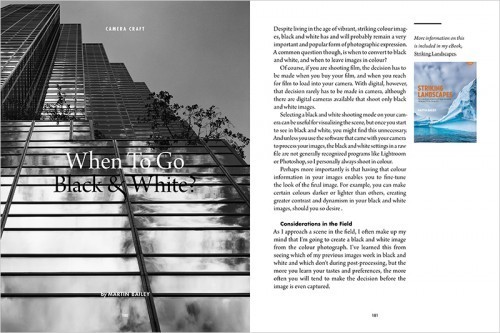

A Brand New PHOTOGRAPH

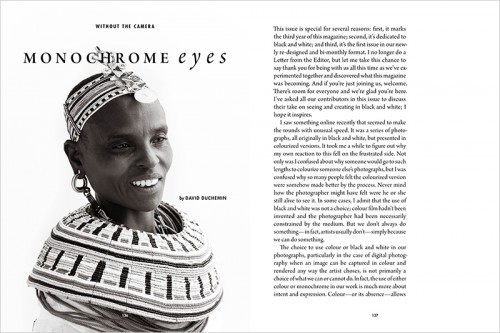

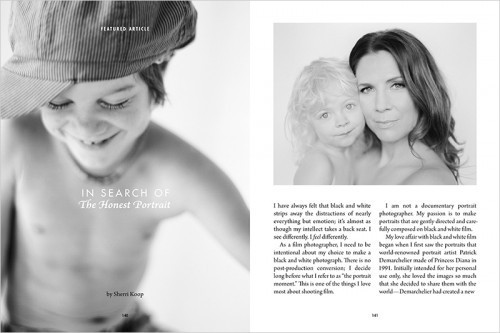

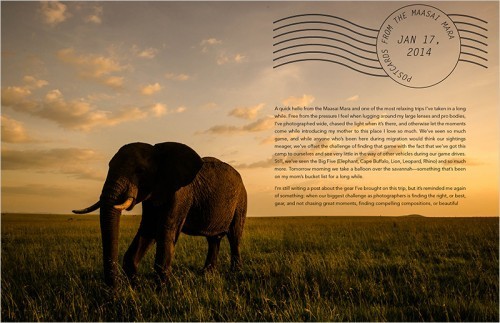

Issue 9 of PHOTOGRAPH has just been released and it rocks. It’s a brand new format, making it much more readable on devices like the iPad, and completely re-designed. It’s also the first in our third year (THREE YEARS!), and with this we’re moving from a quarterly magazine to bi-monthly. 6 great issues a year. And it just keeps getting bigger – this issue is 230 pages long and completely ad-free – just page after page of great photography and teaching. Issue 9 has a focus on Black & White photography and you’ll be blown away by the portfolios: Jason Bradley’s stunning underwater work, Carla Coulson’s lively portraiture, Julia Anna Gospodarou’s dramatic architectural work, and Satoki Nagata’s night-time photography on the streets of Chicago. We’ve also go articles by John Paul Caponigro, Bruce Percy, Guy Tal, Piet Van den Eynde, Adam Blasberg, Martin Bailey, Chris Orwig, and me.

My goal is simple – I want to create something truly beautiful, and showcase the work of photographers that inspire and educate. And I want it to be killer value. I want it to be the kind of magazine you’re proud to tell others about. We’ve had some amazing issues up to now, and I think this one gets us even closer to my dream. The photographs are amazing, the interviews are insightful, and the education is top-notch, covering everything from how we see to how we create.

Download Issue 09 of PHOTOGRAPH this week for only $6.40 – that’s 20% off the normal price of $8. It’s like having a subscription with the luxury of choice. But you don’t want to miss this issue.

October 5, 2014

Study the Masters: Edward Burtynsky

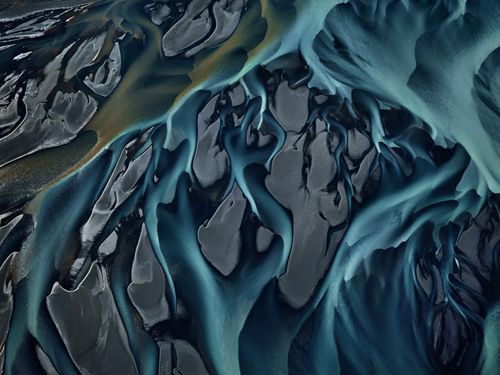

Thjorsá River #1Iceland, 2012, copyright Edward Burtynsky

Thjorsá River #1Iceland, 2012, copyright Edward Burtynsky

“We took what we needed from the Earth and this is what we left behind. That is the informational layer of my work, but there is also a political layer and an autobiographical one.”

Edward Burtynsky (1955 – present) is still very much alive and working today. One of Canada’s most respected photographers, his large-format photographs of industrial landscapes and man’s impact on the land are stunning. I spent time at an exhibit of his this summer in Vancouver, and was deeply moved by his sweeping views of landscapes altered by industry: hauting images of quarries in Italy, mine tailings in Canada, and shipbreaking in Bangladesh, among others. His work shows an awareness of scale and pattern, and an awesome juxtaposition of beauty and man’s terrible impact. It’s easy to see his early influences, too, like Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston.

Like all of us, Burtynsky is a product of his upbringing, and it’s no surprise that a man who grew up in industrial St. Catharines, Ontario, with a father who worked in automotive manufacturing, also ended up working in both mining and automotive assembly lines, before going to art school. Edward’s father, in daily contact with PCBs, died from cancer at 45, Edward was only 15 at the time. Knowing this gives a depth to Burtynsky’s work and makes it more human. More than a study in lines and clever use a scale, these are often painful photographs that demand a response from the reader. His large format work shows incredible detail and while I highly recommend you look at his work online and in books, if you have a chance to see Burtynsky exhibited, do so. As someone who loves landscape photography, and has more than a passing interest in photography as a means of expression and social change, Burtynsky is deeply inspiring.

Nickel Tailings #34Sudbury, Ontario 1996. Copyright Edward Burtynsky

Nickel Tailings #34Sudbury, Ontario 1996. Copyright Edward Burtynsky

Rock of Ages #7Active Section, E.L. Smith Quarry, Barre, Vermont, USA, 1991

Rock of Ages #7Active Section, E.L. Smith Quarry, Barre, Vermont, USA, 1991

Copyright Edward Burtynsky

“Residual landscapes tell us something important. We take what we want, then leave the residue of our taking. Once we take what we value, the voids that remain are very revealing.”

There’s a great video here (almost 7 minutes), from the Vancouver Art Gallery, and longer documentaries here:

Manufactured Landscapes, by Jennifer Baichwal

Watermark, co-directed by Jennifer Baichwal and Edward Burtynsky

Here are two gorgeous books of his work, the first among my favourites – Manufactured Landscapes, (Amazon Link), and Quarries (Amazon link) Highly recommended!

October 3, 2014

The Next Step

Q: I’m a nature photographer with what I’ve been told is a reasonably solid portfolio, and I blog fairly regularly. I make a little money with my photography, but I think I could do more to increase the income a bit. I’m ready to take the next step toward living my dream. I need to market myself beyond my local area, but I just don’t know where to begin, since like other photographers, I suck at self-promotion. WHO do I reach out to and HOW do I approach them? Suggestions appreciated. ~Ron.

A: Ron, thanks for the willingness to be honest about this stuff. I hope you’ll be OK with a little tough love, because I’m not sure any amount of beating around the bush is going to help. All the same, this is just my opinion. Take what resonates, sleep on the rest, then discard what doesn’t stick.

First, your portfolio is full of nice images. Fine images. Technically competent images. But I don’t get a sense of what sets you apart from any other photographer out there that is shooting pretty landscapes. The next step for you might first be the pursuit of some deeply personal projects, and the struggle to create bodies of work that work together in a more powerful way than your images do now. You might sell a few of these images, but if you want to place them consistently in larger publications or curated stock libraries, you’ll have to give them something more. That something, I truly believe, is you. More of you. I don’t know how to tell you to do that, but I don’t sense you’re taking risks, or telling stories you are passionate about. I don’t get a sense of depth and for the most part see nothing – yet – that I’d call an identifiable style. Style isn’t something to strive for, it’s a by-product, but it matters. Nevertheless, that’s a lifelong journey. You’ll strive for this for the length of your career. But if I can be crass, I don’t get a sense that you’re shooting with your balls.

Second, if you suck at self-promotion it’s not because you lack the genes. I hear this from photographers so much and it drives me nuts. What most of us mean is “we haven’t taken the time to learn to promote ourselves,” or “we haven’t taken the risks required to put our work in front of new audiences,” or, “we haven’t been creative enough and we stopped when we ran out of our first ideas.” So I’m going to bounce the question back to you, but I’m going to reverse it because you can’t know HOW until you know WHO.

Who do you want to work for? All of this stuff, selling our work to any audience, comes down to this – what value do you offer to them? What itch do you scratch for them? What audience has that itch more than others? Is it magazines? Is it postcards? Stock? Is it prints on the walls of doctors and dentists? Is it prints in a local gift shop selling to tourists? Is it all of those and some I’ve not mentioned? Hopefully you’ll cast your net wide and see what lands. But until you’ll come up with a list of possibilities, and then go and talk to them – it’s basic research – about what they need, you can’t know how to make a valuable offer, or pursue mutually beneficial collaborations. Every audience is different. They all have different needs, and we can meet some of those better than others. Find those. Get to know them. Meet people. Have honest conversations. This is all – all of it – a relational game. Yes, you need – NEED – to have something they want, and that’s partly a really great product or service, but it’s also how you bring that product to them.

So my suggestions? Work your ass off on bodies of work that make you deeply happy and be so good at it that people take notice. Then find a way to make that work valuable to an audience. Make a list of your top 20 possibilities. Then hit the bricks. Talk to those people. Take them to coffee. Ask them the hard questions: would you pay for this work? Does it have value to you? Would your customers see value in this work? Am I missing something? How can I serve you?

Find an audience with an itch that you are excited about scratching. Then do that every day in every way you can think of. Serve them relentlessly. Listen to them relentlessly.

All sales comes down to an honest, relational, scratching of itches. Find an audience to whom you bring value. Maybe it’s not direct sales of prints or licences. Maybe it’s live lectures because your photography is good but combined with your public speaking, it’s a killer combination. Maybe it’s not finding clients at all, but teaching others. However you do it, it’ll be different from the way anyone else does it. No systems, no shortcuts. In my experience, photographers – otherwise very creative – don’t get creative enough with their thinking on this stuff. Easier to just think about our next lens purchase, right? Many, many photographers struggle with this, and it’s not always because they don’t have amazing work – in fact there are plenty of rather mediocre photographers (relatively speaking I’d include myself in this category) making a good living because we hustle and we think creatively and we don’t give up when the first ideas, all the obvious, low-hanging fruit, haven’t worked.

The next step, my friend, is to go all in. And to keep at it. Find an audience with an itch that you are excited about scratching. Then do that every day in every way you can think of. Listen to them relentlessly. Serve them relentlessly.

If you want more of this, Ron, check out my books: VisionMongers, Making a Life and Living in Photography, and How To Feed A Starving Artist.

While I’ve got the time I’m trying to be more available to my community. If there’s something you’d like to engage with me on, leave a question in the comments. I’ll try to answer all that I can – some in the comments themselves, some as blog posts. Ask me anything.

September 30, 2014

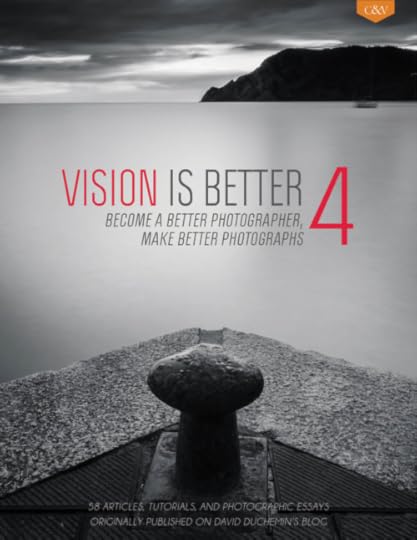

Vision is Still Better

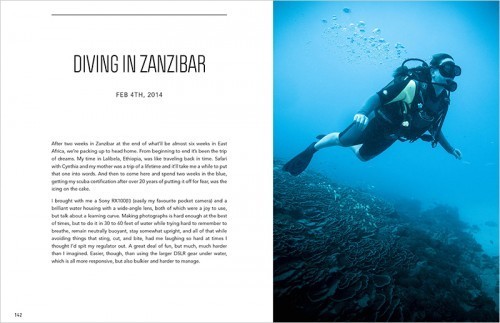

Several years ago I was asked if I’d consider doing something like a yearbook for my blog – a curated compilation of the best stuff, minus the posts where I introduce a new book or workshop – so that people could access my stuff offline in an easy-to-read kind of way. Vision Is Better, the first one, was so well received, we’ve continued to do it. Today we’re releasing Vision is Better 4, and we’re doing it in the same soft-sell way we’ve done it before, letting you know that this is the best from my blog – which you can always get for free if you’ve got the time and bandwidth to do so – only in a great-looking, convenient, read-it-whenever-you-want-including-on-planes-and-stuff format. There’s 50 great articles and stories, and lots of big images from my Postcards From… series.

I believe in this stuff or I wouldn’t have written it. I think these conversations and thoughts and ideas that I blog about, and the techniques I teach, will make us better photographers. If having this on your laptop, or mobile device, in a tightly curated form, is of value to you, then it’s all yours. And it’s still just $5 for the downloadable, DRM-free, PDF. Except this week. if you jump on it now it’s only $4. And if you haven’t got the full set, you can get them all – this week only – for $12 – that’s 40% off and you’ll get just over 200 great articles to teach and, I hope, inspire.

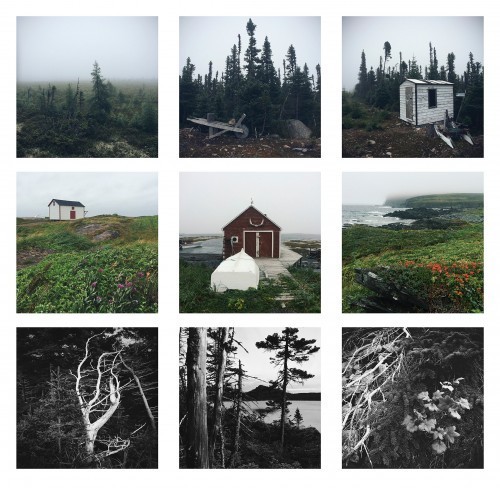

Bodies of Work

Another question from my recent Q&A on Facebook. Some of the questions needed more time and space to answer, this is one of those:

How do develop from taking random images to working on projects? What makes a good project? When is it finished?

First, I think it’s important to recognize that there are no rules on any of this. The big question is this: what do you want to create? In the case of projects, what I will call a body of work, I think what transforms random individual images into a body of work is cohesion – they work together in some way. How they work together is where you need to get creative. Perhaps that cohesion is created by visual cues – like a similar treatment in post-production, and perhaps that cohesion comes from a concept or an idea that will get expressed in different ways. Or maybe it’s both. This is purely my own opinion, but I think the more those images work together, complementing each other but filling in different parts of the larger picture, the stronger the project will be. So for me that means – like a photo essay – a variety of compositions – from very wide to very intimate. Those can provide a rhythm that I think is important in our experience of the larger body of work.

Does that mean I am aware of the body of work while I’m making photographs? Well, yes and no. I generally get a sense of things the further they progress, and the more photographs I make the more I know the direction that it’s taking, and I know this because it’s what feels right to me. So much of what I photograph is a reaction to a place and I never know what that reaction will be, so it’s progressive. It also means it takes time, and it takes play. I need to experiment, especially at the beginning, with different ways of expression. Is this a black and white series or colour? Does it share a colour palette, or is the visual unity accomplished in some other way – perhaps all the images are horizontal 16:9 frames, or vertical 4:5 frames. And some of that too, will depend on how I plan to show this work. Will it be framed, or will it be a book? Or is it both? None of these questions have right answers, it’s more about possibilities, following my curiosity, and knowing it when I see it.

What makes a good project, for me, is a definable scope or idea. Right now I’m working on an idea for a book about my experience of Canada, particularly the wilder parts of this country. Knowing what will be in the book, and what will not is helpful to me. So in this case, it’s Canada at the edges, the parts that really draw me. It’s Yukon colours and bears and coastal scenes, not the Prairies, which are certainly part of Canada, but don’t have a place in this particular body of work. Constraints help me. And in this case, the book will a body of work comprised of multiple smaller bodies, so the challenge will be creating smaller projects with a visual unity, that can also be woven into a larger whole, the differences between those projects are what will give the book its rhythm and help me avoid homogeny.

As for when it’s finished, well that is a harder one, but again, flexible constraints help me. I like deadlines. And sure, they can move – because they serve my creative process, not the other way around – but knowing it’s done when I reach my deadline, or when I meet the conditions of another constraint (for example, I will know I am done when I have 24 images that work together and feel right) is helpful to me. Of course, knowing when it feels right means at some point I just have to make a decision, isn’t always easy, but that’s part of creativity, having the courage to be done and getting it out into the world. No more second guessing, no paralysis from the desire to be perfect, just knowing that whatever about it that remains imperfected will have to find its expression in the next project.

And I think that’s also key for me, to move onto something new immediately. To start the exploration into new subjects or new ways of expression, and as quickly as I am able, to find the new project. The more time I leave between finishing one and beginning another, the less momentum I have, and the harder it is to begin.

The hardest question that remains unasked, and for which I can give no answer, is the one we’re always thinking: what should my next personal project be? That’s the hard stuff and all I can say is be aware of where your curiosity is leading you, be aware of what interests you, and of the things that get your blood pumping. Pursue those things and see how far the rabbit hole goes.

September 28, 2014

Finding Your Mojo

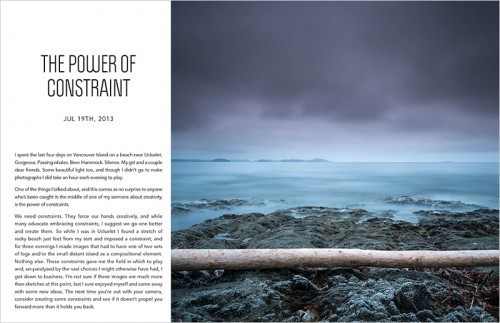

A friend and I, looking for our mojo on Prince Edward Island yesterday. Sometimes we find it, sometimes we don’t, but the search is our job.

Last week I spent some time on Facebook answering questions. It was a lot of fun, and something I’d like to do more often. One question that came up a couple times in different ways was this: I’ve lost my drive, my mojo to pick up the camera. I have so much I want to say with my camera but somehow, I’m blocked!

In my experience when people talk about losing their mojo, they mean their inspiration. We’ve all been there in some way and the longer you do this (your art) the more certainly you’ll have found yourself in a funk. But I like the way we express it: as something lost. And my friend, very few things, once lost, come looking for us. That’s our job. It is we who must go looking for them, and we do that with cameras in hand. We look. We seek. And no, we don’t always find it on the first try. But it is no magic thing. It won’t show up just because you pick up the camera. It must be sought. The only way I know to do that, because it’s not some material thing you’ve just lost under the cushions of the couch, is to do your work.

Go back to where you last had it, when you last felt the inspiration. And get back at it. Shoot a thousand crappy photographs until something ignites your curiosity and you follow that through another thousand frames and find it, there – your mojo, your muse – waiting for you.

My friend, very few things, once lost, come looking for us. That’s our job. It is we who must go looking for them, and we do that with cameras in hand. We look. We seek. And no, we don’t always find it on the first try.

If that doesn’t work, then mix it up. In fact if you lost sight of your muse after photographing one thing, in one way, for too long, it’s a good chance you didn’t lose your muse at all. She got up and left, bored, and will be found when you change things up. Chances are good that you have changed but the way you have done things has not. You yourself have outpaced the artist you once were, and you never noticed your interest, passion, or curiosity waning. Well it’s gone, baby, and you need to put new wine into the new wineskins, to borrow an ancient metaphor. For me that mixing up can mean anything from doing something other than photography for a while, exposing myself to new mediums, or new artists, or even setting old tools down in favour of something new – like an iPhone or film camera. Only you know what that is, and if you’re floundering, just pick something – anything – and see where it leads. But the only way we find something is to look, and the thing with looking is it’s frustrating. We keep looking until we find, and until that moment, after which it seems so obvious, it feels hopeless.

I know this because every trip and assignment I’ve done has felt this way. Each time I begin at zero, each time I have to find the muse, and every time she’s in a new place, and looks a little unfamiliar at first glance, because every work any of us begin, for which we need the muse at all, is a new work. Every day we have to stoke the fire again.

Of course there’s the very real possibility that you haven’t lost your mojo at all, that your muse is there for you, with a million great ideas and the passion and joy – and hard work – that goes with those, but that you’re just paralyzed with fear. I’ve been there, too. The mojo is there alright, you just know your next step will take risk, and that first step in that direction is a step into uncertainty. That, I’m sorry to say, is where my help (if it is help at all) ends. In my experience the muse and all her mojo don’t ask you to go somewhere you can’t handle. But only you can take that breath and move forward. All I can say is, you’ve got this.

Each time I begin at zero, each time I have to find the muse, and every time she’s in a new place, and looks a little unfamiliar at first glance, because every work any of us begin, for which we need the muse at all, is a new work.

I wish I could give you more, but that’s all I’ve got, and it’s all I’ve been able to dredge out of the wisdom of all the artists who’ve gone before us and cared enough to write it down. There are no guarantees – only that if you do not look, if you do not hunt down this recalcitrant muse, and follow your curiosity into corners you’ve never explored, she will remain out of sight. But don’t take all this so seriously that you don’t enjoy the journey. Sometimes – usually, even – the detours are the more scenic routes, and are the point of the journey. More often than not, if we’re willing to take the detours and see them through, we find the muse there, pockets full of mojo.

September 18, 2014

A Bigger Story

Dusk. Fogo Island, Newfoundland. 2014

Do you know why Apple succeeds the way it does? OK, aside from sexy products? They tap into something bigger than technology. Sure, they’re a technology company, and you either love them or hate them, but they aren’t selling phones or computers. They’re selling a narrative. They’re selling Think Different. Creative freedom. Apple is not alone in this. The best companies – the ones with the most loyal followings – sell a bigger idea and connect what they do to that idea.

The other day I opened a discussion about photographers trying to make a living on this craft. This ties into that. I would venture that, on average, the photographers (remember this is about selling your work, I’ll get to the rest of you later…) that are best known and succeeding in the industry are not just plugging their work; they’re telling a story. Their story. They are connecting to some bigger idea that people already care deeply about. Love. Adventure. Fashion. Travel. Cats.

Forget who pays for your work. Who cares about your work? What does your work make others care about? These are not questions for the faint of heart.

The application should be obvious. Find your core. Figure out what stories are most important to you. Now find the audience for that. Photographers who are just trying to sell prints or the odd image license by shooting all over the map are not the ones making a career of it these days. I’d be willing to bet I could go to most of those websites and not be able to tell you what that person truly, deeply, cares about. Or there’d be such a list of varied interests that it’d be meaningless. Give me something to sink my teeth into. Hell, give me something to sink my heart into.

And if you don’t give two shakes about making a living with this, the notion remains as relevant and powerful. People will be more drawn to your work (assuming the work itself is solid) if it’s about something. Relentlessly, unapologetically about something. What themes run through your work? What legacy are you leaving? Forget who pays for your work. Who cares about your work? What does your work make others care about? These are not questions for the faint of heart. They require decisions, and commitment. But I’d go to the mats on this one. If you want to connect to an audience, you need to make them care. The best way to do that is to connect with them over things they already care about.

Say something meaningful, make me lean in and pay attention. Signal wins over noise every time. Be courageous. Be interesting. Speak to my heart and my curiosity.

What story are you telling? What bigger ideas are you tapping into? If you don’t know, neither does your audience. This should be a freeing notion for us. Terrifying on some level, sure, because to some extent it requires that we nail our colours to the mast. But isn’t that one of the reasons we love our favourite artists? It takes courage. But it’s still freeing. It provides a framework, a constraint we freely choose, to photograph only what we care about and letting the rest go. No obligation to be someone else, photograph everything under the sun. It’s a freedom from the frantic, noisy, climate we live in.

When I was in comedy there were times when an audience would get noisy. Turning up the microphone doesn’t work. They just get noisier. What does work is to say something that matters and be less noisy. Lower your voice to whisper if you have to. Don’t match noise for noise. Say something meaningful, make me lean in and pay attention. Signal wins over noise every time. Be courageous. Be interesting. Speak to my heart and my curiosity. And tell a great story with your life and your art. You’ll have all the audience you’ll ever need.

Don’t mistake me for saying it’s easy. It’s not. This is the struggle, the chase, and it’s its own reward on the days it’s not its own form of mental torture. It’s the reason I’m writing more about the creative life these days than I am about the buttons and dials on your camera. That’s easy. Anyone can learn that. This other stuff is hard. It’s also the reason I wrote A Beautiful Anarchy, and started the Beautiful Anarchy blog – if you haven’t bookmarked it yet, here’s the link. If you want to explore these ideas further, check out the book, and the blog.

September 14, 2014

Waiting, in Newfoundland.

I get nervous when things come too easily, which, as it turns out, is not remotely the case on this trip. Sadly, I also get nervous when things are tough and there are no guarantees that my work is going anywhere. That’s the tension I’ve been living in on this trip across Canada, now into its 6th week. I’ve been posting images of the trip on Instagram and here on the blog, but not the work I’ve been chipping away at, which has been misunderstood by at least one reader already who wrote to tell me my work sucked and he was close to unfollowing me. Funny how you can get anything online; presumption and unkindness being in particularly abundant supply.

We don’t create our photographs first for other people. God help you if you do. And if you think other photographers are out there first for you, you’ve got a particularly narcissistic way of looking at what is otherwise a very beautiful world. No, most of us create first for ourselves, to see the world in new ways, to wrestle with that balance between our vision and our craft, and – for me – to create bodies of photographs that work together in a way that they couldn’t do on their own. But the thing about bodies of work is that they evolve, they surprise, and for the impatient among us they take too damn long to give us the first hints of what they are becoming. It’s why I’ve not posted – and won’t be posting – much of my work from this trip, at least for a while. And it’s why you need to be patient with yourself as you create.

Seeing is truly an act of the mind, not the eyes, and the mind gets distracted by a million things; so it seems to me that there are few photographic skills more important than patience.

There are hundreds of photography sites out there, all willing to give you tips and tricks, shortcuts to get you there faster. When you get tired of those, and bumping up against the reality that not a single one of those shortcuts is going to get you where you’re heading (this is a journey, if anything, of many, many shortcuts, so I’m not sure they can be rightly called that), then slow down, take a breath, and think of this work like a long exposure. It’ll take a while. You aren’t doing this for anyone but yourself, so don’t be afraid to go at your own pace, and most importantly – to enjoy it as you go. If you wait until you “arrive” before you enjoy the passage of time, you’ll never do so.

All this came back to me last night, the 8th night on Fogo Island, when, up to the tops of my boots in a bog, I was swatting mosquitoes and eating blueberries I’d picked on the way, and waiting for the light to fall, and making – what – my 2000th frame, and having a wonderful time on the very edge of the world, but uncertain about what I was doing. We’re so very addicted to certainty, and in a craft that relies on the very unpredictable elements of light and time, it’s no wonder we suffer withdrawal symptoms. Add to that our gear, and weather, and the fact that seeing is truly an act of the mind, not the eyes, and the mind gets distracted by a million things; it seems to me that there are few photographic skills more important than patience. And you know what, sometimes the work does suck, but that’s often the first step on the way to creating something beautiful, and if you can’t deal with that – in your own work or the work of artists brave enough to share their process with you – then you’ve got a lot of frustration ahead of you.

(Thank you for your patience. The work I’m creating here in Newfoundland and Labrador is part of a book I’m imagining about Canada at the edges, and my experiences of a land I feel deeply connected to. So I’m sitting on it. Letting it percolate, and allowing it to show me what it’s becoming, rather the other way around. Still, here are two roughly edited images, and if you’re longing for a new desktop wallpaper, you can use both of them for that purpose.)