David duChemin's Blog, page 15

July 30, 2015

Learn To Isolate

This Red Crowned crane was among many, but isolated with a longer lens it creates more impact within the frame than it might have surrounded by context.

It’s been said that photography is the art of exclusion. It’s as important, in making a compelling photograph, to exclude what we do not want within the frame of our image, as it is to include what we want. In fact, when we include what we want without carefully excluding the rest we introduce too much to the image, and we dilute the impact of the elements we were hoping would make the photograph what it is. Honing this art of exclusion is a significant step forward on the photographic journey, and learning to isolate your subject is an important part of that. Here are a couple significant ways you can begin to isolate your subject, and give it greater power within the frame, undiluted by the noise of elements that do nothing to help you tell the story.

POINT OF VIEW

The first and most obvious way to isolate elements with the frame is the intentional use of point of view. What appears and does not appear, in front of, around, and behind, your subject, has a everything to do with where you stand and put your camera. Yes, there are plenty of situations in which moving around will do nothing to get rid of background chaos or unwanted elements, but too often a simple change of position can move that unwanted element in relation to your subject. A little movement to the left or right, standing on a ladder or lying on your belly, can push those elements from the frame. Just playing with our point of view can improve an image with no other changes. Next time you’re photographing something take a little extra time to be aware of what is in, and out, of the frame, and try moving – do a complete circle around your subject if you have to – and see if you can’t strengthen your image that way.

OPTICS

Nikon D800, 16mm, 1/1000 @ f/11. ISO 200

Using a wider lens (16mm) forced me to push in tighter, making the foreground larger relative to the rest of the elements, isolating it in a way a longer lens would not have done.

Of course there are plenty of times that moving in relation to the subject isn’t preferable. Moving changes the perspective, and with it, the lines. Moving changes what the light is doing and if you’ve got your heart set on a backlit photograph, then moving 180 degrees will change the photograph completely. When that happens, it’s time to explore other options. The first one I try is a change of angle of view. Where a change of POV, or point of view, means a change of position of the photographer relative to her subject, a change of angle of view is all about which lens you choose. A wide angle lens, as the name implies, has an angle of view that is extremely inclusive – it pulls a lot into the frame. A telephoto, by definition, is a much tighter angle of view. The most obvious move in pursuing a more isolated subject is to use the longer telephoto lens, and that often leads to beautifully simple images, free from extraneous elements. Next time you’re trying to really isolate something, try backing up and using a longer lens. But that’s the next lesson, so I’m getting ahead of myself. It’s also not the only way to use optics to make a subject stand out.

A wide-angle lens can also be used to isolate, though it’ll involve both a change of optics (put that wide angle lens on!) and a change in position (get as close as you dare!). A wide-angle lens pushed in close will still be a wide-angle lens and will still include more elements than a tighter, longer, lens. So how can that be used to isolate? Isolating an element is about making it more prominent than others, giving it greater visual mass, and diminishing distractions. When you push a wider lens much closer to your subject, in the right circumstances it does two things simultaneously: it enlarges the subject and diminishes the rest. When a longer lens doesn’t give you the look you’re hoping for, or excludes too much of the context, try going much wider and much closer.

MOTION

Nikon D800, 70mm, 1/80 @ f/9. ISO 500

Panning with this Whooper Swan in Hokkaido, Japan, allowed me to both create a sense of motion, and to create a sense of isolation against a background that would otherwise have more visual pull.

Sometimes the use of depth of field doesn’t help. And sometimes it just doesn’t give you the aesthetic you’re looking for. Motion can be a great isolator. When the subject is moving, you can use a slower shutter speed and pan the camera to create a sharp subject against a blurred background. When the subject is stationary, but it’s surroundings are in motion, you can use the reverse technique – keeping the subject sharp while the moving surroundings blur around them. Both techniques require practice, and a slow shutter speed. In the case of allowing the surroundings to blur around a sharp subject, you’ll also need a means to stabilize the camera, like a tripod. A friend of mine uses her handbag, others use beanbags or part of buildings. However you do it, the longer shutter speeds create blur of the once distinct, and distracting elements, and simplify them, allowing you to isolate – or more clearly point to – your desired subject.

These aren’t the only techniques. You can use a shallow depth of field too, (I cover that in Lesson 10 of The Visual Toolbox. This is an excerpt from that book). Consider too, for example, the role of light and the ability to blow out a background or plunge areas into shadow. However you do it, the most important part of this lesson for some will simply be the awareness that intentionally isolated elements can dramatically strengthen a photograph, giving the main subject greater visual mass, and allowing other elements to remain outside the frame, gain reduced visual mass, or fade into blur.

YOUR ASSIGNMENT

Look at a few of the images you love best, from other photographers, and for each image ask yourself one question: what role does isolation play in this image? You might also ask yourself what choices the photographer made to simplify this image and make it as strong as it is. Are there extraneous elements that distract? Isolation is all about simplify an image of unnecessary elements so the most important elements have the best shot at pulling your eye, your attention, and your emotions.

Tell the World! Share this Post.

July 27, 2015

Making Photographs & Magic

When I was 14 I picked up a camera at a neighbour’s garage sale, a little Voigtlander rangefinder that changed my life. Quickly I wanted what we all want at the beginning – more control, more lenses, more gear. My mother gave me a Pentax Spotmatic and a gadget back full of stuff, acquired from a co-worker who had recently lost her father to whom all this belonged, along with a gigantic and aging Linhoff tripod that collapsed on its own whim, often pinching my fingers or sending my camera to the ground. My God I loved that thing.

I loved looking through the viewfinder and allowing the frame to make sense of the world, to bring some order to things. I loved the alternate way of seeing things. Spurred on by Freeman Patterson’s books and a pile of old PhotoLife magazines, I learned my craft, always with this inescapable sense of mystery, curiosity, and excitement. When I started developing my own negs and printing my own work, eventually in my own darkroom, that excitement was accompanied by some heady, indescribable magic. It might have been the chemicals.

I had friends in a band. I photographed them. I want for walks with my massive tripod and a used Soligor 400mm lens that was, at it’s fastest, an f/8. But I insisted on using it with a 2x teleconverter because if there’s one thing better than a boring photograph of a duck, it’s a boring photograph of a duck that’s twice as large in the frame. I didn’t care. It was magic. All of it. I photographed when I could. I made hundreds, and later thousands of truly bad photographs. It was still magic.

Fall colours blaze across Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon Territory, Canada.

And not once did it concern me whether I fit someone’s definition of what a photographer was or was not. I was too busy with the magic of making photographs.

Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon Territory, Canada.

So when I see clever posts on Facebook or the blogs of other photographers, defining what is and is not a photographer, and who does and doesn’t get to experience the magic, my heart sinks a little bit. I got into this to make photographs, not make distinctions.

The world is full of people trying to do what they love, and some of them, like I was at the beginning, are doing it in stops and starts. They’re making some truly bad photographs with hand-me-down gear and tripods we snicker at. And some of them will, one day, make photographs that amaze me. Almost two years ago I gave a presentation at a weekend conference in New Brunswick, and standing in the front row with hundreds of others, giving me a standing ovation, was Freeman Patterson, a man who is still my hero as much for his photography as for his humanity. It brings tears to my eyes just thinking about that moment. I’m still just making a lot of really bad photographs. I do that to get to the few really good ones. I’m glad I didn’t stop when others snickered at my gear. I’m glad there was no internet, no Facebook, and no clamouring voices discouraging me at the time.

We don’t get to decide who is and who isn’t. We get to decide if we are, and having made that decision, to go make photographs, to feel the joy of creation.”

Amateurs, don’t listen to the voices that tell you you’re not a so-called real photographer. Find voices you can respect as much for their humanity as you can for their art, because they’re connected. “Ridicule,” I’ve read somewhere, “is a terrible witherer of the imagination. It binds us where we should be free.” That applies to both those who listen to it and those from whom it comes. Go find the magic, wherever you can. Make the thing that gives you joy, and in the way that fills your imagination. Don’t worry about whether they call you a photographer or not. It’s not what they do or don’t call you, it’s what you make. What you give back. In the end it’ll be the people that show us a new way of seeing the world that get our attention. And seeing the world based on who’s in and who’s out, who is and who isn’t – that’s the oldest way of seeing the world. There are better ways to inspire beauty and magic.

Tell the World! Share this Post.

July 24, 2015

Chasing Photographic Style.

“Spend any time with photographers talking about the work of other photographers and the words “he’s got a really unique style” will slide out of someone’s mouth faster than hands off a greased pig.”

We value style, forms of expression so unique to shooters that you can identify their work immediately. Show me a Jill Greenberg photograph, or an Annie Leibovitz cover and their name comes to mind without a conscious thought, much less looking for the photo credit.

So valued is the notion of style that it won’t be long before someone writes a Dummies book about it and cashes in on our hunger for it. But like anything we value, we value it for its scarcity or its difficulty in attaining it. If it’s so easily achieved that it could be found between the yellow covers of a Dummies book, it’s nowhere as valuable as we thought.

Do you have a style? Maybe. Maybe not yet. Maybe you have a couple of them. But it could be entirely the wrong question. Style is a by-product. It is the end and not the means, and there are no short-cuts. Truly authentic style is not something you can conjure or fabricate. It’s a result of shooting thousands of images that express your unique thoughts, feelings, opinions with increasing faithfulness. It’s something that comes as you refine the means by which you express your vision.

“Do you have a style? Maybe. Maybe not yet. Maybe you have a couple of them. But it could be entirely the wrong question. Style is a by-product.”

There’s nothing wrong with seeking to do things in a unique form, but seek to be different for the sake of being different and you won’t have images that express your vision, you’ll have photographs that are merely different. You can get that in a million ways that have nothing to do with good photography. You can be different without ever saying anything. You yourself are unique – you have ways of seeing your world that are unlike those of anyone else – so find ways of more faithfully expressing that and your style will emerge.

There’s nothing wrong with seeking to do things in a unique form, but seek to be different for the sake of being different and you won’t have images that express your vision, you’ll have photographs that are merely different. You can get that in a million ways that have nothing to do with good photography. You can be different without ever saying anything. You yourself are unique – you have ways of seeing your world that are unlike those of anyone else – so find ways of more faithfully expressing that and your style will emerge.

Perhaps it’s helpful to think of this through the lens of a different medium, like films. A good film that bears the style signature of a great director is not uniquely identifiable because someone like Coppola poured his efforts into being different. He pours his efforts into creating a film that, as closely as possible, tells the story in accord with his unique vision. Creating films that are faithful to your vision is the goal, finding over time that your body of work reflects a style unique to you is a by-product.

Of course, there’s room to be intentional about refining the expression of your vision. The more you study and understand the visual language tools available to the photographic storyteller, the more consciously you can chose one set of tools over another. The danger lies in thinking that one set of tools, chosen for stylistic reasons, will always be the best choice of tools for every image. If McLuhan was right about the medium being the message, then we need to be conscious that our choice of tools always has implications on the message itself. Choosing tools based only on stylistic criteria can result in highly-stylized images that say precisely nothing.

Of course, there’s room to be intentional about refining the expression of your vision. The more you study and understand the visual language tools available to the photographic storyteller, the more consciously you can chose one set of tools over another. The danger lies in thinking that one set of tools, chosen for stylistic reasons, will always be the best choice of tools for every image. If McLuhan was right about the medium being the message, then we need to be conscious that our choice of tools always has implications on the message itself. Choosing tools based only on stylistic criteria can result in highly-stylized images that say precisely nothing.

I wrote this little rant several years ago. Now, with those years under my belt, I believe this more than ever. But I also believe that there’s value in being intentionally consistent, at least within a body of work. I think one image can be powerful, but a series of images that work together because they follow a theme, and visually compliment each other, that have a flow, and together tell a bigger story, or create a more textured poem than one image alone can do – that’s magic. And that’s the thing – eventually – someone will call style. You’ll probably get there faster if you don’t chase it, and you’ll be more creative – and probably happier – if you’re not bound to it.

July 15, 2015

Just Print It – Epson P800

I’m running out of ways to creatively say some version of “print yer damn work!” But seriously, print yer damn work. Live with it. Study it. Hold it in your hands. Give it away. Experience the joy of seeing it matted and framed and hung on walls. For some that means using a service like mPix or WHCC or, my preference these days, Artifact Uprising. For others it means printing at home. Printing at home – doing it yourself – is a learning curve, and it means buying a printer, but it’ll teach you more about your photographs than just looking at it on a screen. Everyone I know that prints does it for a variety of reasons, but almost all of them agree – it makes them a better photographer. Print your work.

If printing at home is an option and you’re looking for a recommendation, then here’s mine: get Martin Bailey’s eBook, Making the Print (it’s only $5), and get an Epson P800 printer. The P800 replaces the much-revered 3880, and from reviews, and my own first experiences, it’s excellent. I’ve just finished matting and framing and putting up 3 images from recent work in Venice, and they look incredible. The printer isn’t huge, at least not compared to the massive sofa-sized 7900 I used and swore at for the last 2 years (it made beautiful prints but was a beast), and it sits nicely on my work surface. It’s easy to use, has a great interface, and unlike the predecessor, the 3880, it prints wirelessly (set up was super easy, which is good because Epson still won’t put a freaking USB into the box) and it takes roll media with the sold-separately roll spindle. It prints up to 17″ wide, which means I can use my favourite 17×22 papers. I can’t comment on other brands – I’ve used 4 different Epsons in the last 5 years – but my first impressions of the Epson P800 are the strongest I’ve had so far. I already love printing on this – and if you love printing, instead of feeling like you need to drink heavily before you turn the thing on, you’ll probably do it more. (You can find it on Amazon.com for $1200)

Don’t be that photographer that never sees his photographs in the real world, or whose best work only ever sits on her harddrives and iPhones. Print it. Get it out into the real world. With whatever printer or service you prefer – but seriously, print your work.

Don’t forget, we’re going offline with the blog next week, but maybe check out the new Vision Is Better show on YouTube. Episode 07 – It’s Not About the Mirrors, comes out on Monday. Join me as I roll the magic 8 ball and tell you which mirrorless camera you should really get.

July 14, 2015

It’s the Vision Is Better Show!

Today we launched the Vision Is Better show, a mostly-weekly 10-15 minute video podcast about photography. I’ve pre-recorded the first 6 of them and they’re live now on You Tube and I’m hoping that you’ll do 2 things for me – the first is subscribing. The second is asking questions in the comments. I’m hoping these questions will become the pool from which I draw my material, so the show can be as relevant to you as possible. So – would you head over there today and check them out, subscribe, and leave some comments – let me know who’s watching and what you’d like me to talk about? Questions, people, I need more questions!

In the first 6 episodes I talk about my gear for grizzlies, why I hate my DSLR, how I edit, how I processed my grizzly series, histograms and the Church of Blown Highlights, how I take care of my cameras on the road, and of course, vision. Join me!

As an added bonus there’s an awkward screenshot every week. Who wouldn’t love that?

As an added bonus there’s an awkward screenshot every week. Who wouldn’t love that?

Finally, a note about this blog. It’s getting a little long in the tooth. If it gets any older it won’t remember my name and I’ll have to feed it mushed peas. And it’s slow as Sunday drivers to load. So next week we’re going to pull it all down, put up one of those lame UNDER CONSTRUCTION pages and take what I hope is only 3-4 days to get the new template installed, customized, and up and running. Sorry for the down-time, but I just can’t take it any more. It’ll be a much faster, device-compatible site, that I think you’ll enjoy reading a lot more. Stay tuned. Until then, head over to You Tube to check out the Vision Is Better show. I’m excited about this and can’t wait to do episodes as I travel.

July 10, 2015

Tell Stronger Stories

Through the ages, myth and stories have been the primary vehicle for communicating meaning and truth. They are not merely the stuff of bedtime tales. The primary storytelling medium in our culture is the cinematic film, and given the billions of dollars attached to the film industry, and the royal status given to its stars, it should be clear how important story is to us.

Story told in a movie or novel, and story told in a single frame of a photograph, are very different kinds of story. One occurs in the briefest moment, perhaps 1/500th of a second, while the others are told over longer periods – hours, days – and reflect experiences or circumstances that span days, weeks, years, even generations. What makes it difficult to tell a story within a single frame is the inability to form a classic narrative, but this is doesn’t make storytelling impossible; it simply confines us to certain conventions that, when understood, allow us to tell, or at very least imply, more powerful stories.

An understanding of the elements of story and how they can be incorporated into your images will make stronger images. It doesn’t matter if you do reportage, advertising, weddings, or wildlife; a sense of story will make your images more engaging and compelling.

Five aspects of storytelling come to mind as I consider the unique challenges of storytelling within the confines of a single photographic frame; themes that tie the image to our deeper, more universal human experience; conflict; mystery; action; and the relationships between the characters.

Theme

A story succeeds on empathy, and fails for lack of it. If you don’t care, it’s not a relevant story.

Ask a friend what the last film they saw was about and the usual answer will be a recap of the plotline. Character X did this and then this happened and to get out of it he did this and this, etc. But movies are not about the plotline. The plotline tells the story, but the story is about something more. Perhaps it was about revenge or love or the search for meaning – the deeper theme that moves the film from beginning to end. The plot is merely the way we tell the story of the theme. “What’s it about?” is not the same as “what happened?”

Photographs, if they are to tell or imply a story, must be about something. Truth, justice, love, or the lack of, or search for those things, are strong universal themes. Loneliness, betrayal, our tendency to self-destruct, death, resurrection, the bond of family – all of these are strong themes and the more universal a theme you echo in your image, the more powerful it will be and the more broad the audience to whom it will be powerful. If you’re already thinking that this is a little to deep for your style of photography, what about themes like peace, solitude, or beauty?

Make your images about something. It doesn’t have to reflect deep brooding themes. It can be a photograph of an orchid that’s about serenity or the wonder of the natural world. It can be about innocence or the simple power of a line. But even an image of crocus breaking through the crust of snow and ice can resonate with themes of resurrection and new life. Whatever it is, make it about something so the people that see your image feel something, so they care about your image. Some of these, I admit, are more poems than story. And that’s OK. As much as we resonate with great stories, or even the implication of story that we find in great single moments, it is not the only way we communicate. Not every compelling photograph has a sense of story any more than we can say every great piece of writing is a narrative, which would exclude the worlds most beautiful poetry. Some photographs are more poem than story and they move us in different ways as much as they are created in different ways and for different reasons.

Either way, the more powerful and universal the theme in your image, the more powerful and universal the impact of the image. To put it another way, the more deeply they care, the stronger the story.

“An understanding of the elements of story and how they can be incorporated into your images will make stronger images. It doesn’t matter if you do reportage, advertising, weddings, or wildlife; a sense of story will make your images more engaging and compelling.”

Conflict – The Heart of Story

In his screenwriting text Story, author Robert McKee writes that “the music of story is conflict,” that, “nothing moves forward in a story except through conflict.” And he should know. Robert McKee is the script doctor behind more great movies than any other.

But how do we bring conflict to play in a frame? Obviously we can photograph moments of actual open conflict – guns and fists and angry gestures. But what about stories that are not about open conflict? What about stories that are about something else but still need conflict to move it forward?

Conflict in a still photograph is most often shown in contrasts. Not just the visual contrast of dark tones to lighter ones, but the more conceptual contrasts of big to small, mechanical to natural, smooth to textured. Any pair of juxtaposed or implied opposites create what I call “conceptual contrasts,” and those can provide the same thing to the story in a still frame as conflict does in a movie.

Tom Stoddart created a powerful image in Rwanda: a little boy cowering in the shadow of a larger figure with hands on hips. The contrast of big vs. small creates both a visual and a conceptual conflict. In the same series he has an image of a small Rwandan boy sitting under the larger figure of a Caucasian soldier – small African boy vs. large European man. The contrasts imply conflict and creates, or implies, story, even without the captions to clarify. We are moved with no further information because of the strength of those contrasts and what they trigger in us.

Ami Vitale has a gorgeous photograph of soldiers in Kashmir; they sit in their camo fatigues, guns on laps, in bright yellow shikara boats of Lake Dal, festooned with ribbons and hearts, painted in primary colours. Hearts and guns, camouflage and clown-colours. The conflict comes from a clash of ideas – the primary colours of childhood and innocence clashing with the guns and colours of war.

This concept applies to non-reportage images as well. Even a sunset shot contains elements of conceptual contrast – sky vs. earth, sun vs. water, light vs. dark. Strongly opposed or contrasting elements create a compelling sense of conflict which is the heartbeat of Story.

“Either way, the more powerful and universal the theme in your image, the more powerful and universal the impact of the image. To put it another way, the more deeply they care, the stronger the story.”

Leaving Clues and Provoking Questions

A great storyteller doesn’t tell absolutely everything, she tells enough to make you care, to tell the story and move the plot, and no more. Extraneous details don’t provide anything more than confusion. In fact, more than just cluttering the story, a flood of details kills the mystery and the engagement. A good story has a sense of wonder, it raises curiosity, it leaves something untold for us to gnaw on. Perhaps it’s a glance out of frame; we’re familiar with the look of affection she has on her face, but who is she looking at? A face moves into silhouette as you press the shutter, and suddenly a photo of a specific woman is a photo of a woman around whom there is some mystery.

What you leave in the frame must be part of the story. It must be part of the visual plot, even if that’s simply establishing the setting. But you need to be very selective. Leaving a cluttered background by shooting wide & indiscriminately does not establish setting; it’s lazy photography. Each element must be chosen intentionally, even if that occurs intuitively on some level. The more elements within the frame the less power each of them has and your story becomes diluted.

Leave enough clues to tell the story and exclude enough to create a sense of mystery. Unanswered questions engage a viewer and create an interaction between the image and the viewer – a deeper level of viewing that allows us to think and feel more connected to, and touched by, the story.

The choices you make about what to leave in and what to cut out are editorial choices that will determine how clearly the story is told.

“A good story has a sense of wonder, it raises curiosity, it leaves something untold for us to gnaw on.”

Action

Ultimately, story is about change. Something happens, provokes the protagonist to action, which changes things. That’s what conflict is about. The stronger the conflict, the more extreme the action that is provoked, and the greater the change that results. In the still frame a story is often most successfully implied by choosing not only an action but the strongest visual expression of that action. A man throws a baseball. In a video of that action there is a smooth sequence of moves from a wind-up through to a release. In a still frame, we have choices to make. At what point does the throw look most like a throw? At what point is the energy strongest? Does a slower or faster shutter better help communicate the speed of that throw? Does our chosen composition exaggerate that energy or impede it? And then, do we include, if we’re still using the baseball scenario, the batter or the person catching the ball, and thereby include a second element and the possibility of an implied relationship between the two?

Relationships

Relationships of elements to each other within the frame are key compositional tools that give us – or deny us – solid clues as to the unfolding story within the frame.

One object larger than another implies something about the relationship of power between them. The space between two elements or characters within the frame tells something about their connectedness or how they relate to each other. Simply changing your point of view, camera angle or choice of lens can dramatically change the feeling and implied relationship within a photograph.

As an example, using your telephoto lens’ ability to compress space is an excellent way of bringing elements that are distant from each other into a perceived proximity. To go back to the scenario of the baseball pitcher, an image of that pitcher taken with a standard lens, and from the right angle, will show the batter, and the crowds, in the distant background. The same scenario captured with a 200mm lens will compress the foreground and distance and create a stronger implied relationship between the pitcher and the batter, excluding the context of the stadium. In terms of story, one places the main character within his setting, even making a third character of the crowds, the other creates a relationship of closeness and proximity, between the pitcher and batter, as though the two are inseparable, and focuses more on the conflict between them.

If you wanted to show the same pitcher in an even more imposing setting, and show how high the stakes are, you might choose to use a much wider angle lens and get closer to the pitcher. The properties of the wide lens will make the stadium seem more vast, the crowds larger.

Which lens you use will depend on the story you want to tell. In the same way your other choices will be made based on the story you’re telling or the way you want to make your viewer think or feel about the characters/elements within the frame.

What choices you make depend on the story you’re compelled to tell, but being conscious of these tools you use will make your storytelling more intentional and compelling, which in turn will give the reader of your photographs the best shot at feeling what you want them to feel, and experiencing your photograph more deeply.

Story was first published in my Without The Camera column in PHOTOGRAPH magazine, Issue 8. You can get back issues of PHOTOGRAPH, an ad-free and timeless magazine about the art and craft of making photographs here, including 4-issue bundles for $24.

Tell the World, Share this Post.

Story

Through the ages, myth and stories have been the primary vehicle for communicating meaning and truth. They are not merely the stuff of bedtime tales. The primary storytelling medium in our culture is the cinematic film, and given the billions of dollars attached to the film industry, and the royal status given to its stars, it should be clear how important story is to us.

Story told in a movie or novel, and story told in a single frame of a photograph, are very different kinds of story. One occurs in the briefest moment, perhaps 1/500th of a second, while the others are told over longer periods – hours, days – and reflect experiences or circumstances that span days, weeks, years, even generations. What makes it difficult to tell a story within a single frame is the inability to form a classic narrative, but this is doesn’t make storytelling impossible; it simply confines us to certain conventions that, when understood, allow us to tell, or at very least imply, more powerful stories.

An understanding of the elements of story and how they can be incorporated into your images will make stronger images. It doesn’t matter if you do reportage, advertising, weddings, or wildlife; a sense of story will make your images more engaging and compelling.

Five aspects of storytelling come to mind as I consider the unique challenges of storytelling within the confines of a single photographic frame; themes that tie the image to our deeper, more universal human experience; conflict; mystery; action; and the relationships between the characters.

Theme

A story succeeds on empathy, and fails for lack of it. If you don’t care, it’s not a relevant story.

Ask a friend what the last film they saw was about and the usual answer will be a recap of the plotline. Character X did this and then this happened and to get out of it he did this and this, etc. But movies are not about the plotline. The plotline tells the story, but the story is about something more. Perhaps it was about revenge or love or the search for meaning – the deeper theme that moves the film from beginning to end. The plot is merely the way we tell the story of the theme. “What’s it about?” is not the same as “what happened?”

Photographs, if they are to tell or imply a story, must be about something. Truth, justice, love, or the lack of, or search for those things, are strong universal themes. Loneliness, betrayal, our tendency to self-destruct, death, resurrection, the bond of family – all of these are strong themes and the more universal a theme you echo in your image, the more powerful it will be and the more broad the audience to whom it will be powerful. If you’re already thinking that this is a little to deep for your style of photography, what about themes like peace, solitude, or beauty?

Make your images about something. It doesn’t have to reflect deep brooding themes. It can be a photograph of an orchid that’s about serenity or the wonder of the natural world. It can be about innocence or the simple power of a line. But even an image of crocus breaking through the crust of snow and ice can resonate with themes of resurrection and new life. Whatever it is, make it about something so the people that see your image feel something, so they care about your image. Some of these, I admit, are more poems than story. And that’s OK. As much as we resonate with great stories, or even the implication of story that we find in great single moments, it is not the only way we communicate. Not every compelling photograph has a sense of story any more than we can say every great piece of writing is a narrative, which would exclude the worlds most beautiful poetry. Some photographs are more poem than story and they move us in different ways as much as they are created in different ways and for different reasons.

Either way, the more powerful and universal the theme in your image, the more powerful and universal the impact of the image. To put it another way, the more deeply they care, the stronger the story.

“An understanding of the elements of story and how they can be incorporated into your images will make stronger images. It doesn’t matter if you do reportage, advertising, weddings, or wildlife; a sense of story will make your images more engaging and compelling.”

Conflict – The Heart of Story

In his screenwriting text Story, author Robert McKee writes that “the music of story is conflict,” that, “nothing moves forward in a story except through conflict.” And he should know. Robert McKee is the script doctor behind more great movies than any other.

But how do we bring conflict to play in a frame? Obviously we can photograph moments of actual open conflict – guns and fists and angry gestures. But what about stories that are not about open conflict? What about stories that are about something else but still need conflict to move it forward?

Conflict in a still photograph is most often shown in contrasts. Not just the visual contrast of dark tones to lighter ones, but the more conceptual contrasts of big to small, mechanical to natural, smooth to textured. Any pair of juxtaposed or implied opposites create what I call “conceptual contrasts,” and those can provide the same thing to the story in a still frame as conflict does in a movie.

Tom Stoddart created a powerful image in Rwanda: a little boy cowering in the shadow of a larger figure with hands on hips. The contrast of big vs. small creates both a visual and a conceptual conflict. In the same series he has an image of a small Rwandan boy sitting under the larger figure of a Caucasian soldier – small African boy vs. large European man. The contrasts imply conflict and creates, or implies, story, even without the captions to clarify. We are moved with no further information because of the strength of those contrasts and what they trigger in us.

Ami Vitale has a gorgeous photograph of soldiers in Kashmir; they sit in their camo fatigues, guns on laps, in bright yellow shikara boats of Lake Dal, festooned with ribbons and hearts, painted in primary colours. Hearts and guns, camouflage and clown-colours. The conflict comes from a clash of ideas – the primary colours of childhood and innocence clashing with the guns and colours of war.

This concept applies to non-reportage images as well. Even a sunset shot contains elements of conceptual contrast – sky vs. earth, sun vs. water, light vs. dark. Strongly opposed or contrasting elements create a compelling sense of conflict which is the heartbeat of Story.

“Either way, the more powerful and universal the theme in your image, the more powerful and universal the impact of the image. To put it another way, the more deeply they care, the stronger the story.”

Leaving Clues and Provoking Questions

A great storyteller doesn’t tell absolutely everything, she tells enough to make you care, to tell the story and move the plot, and no more. Extraneous details don’t provide anything more than confusion. In fact, more than just cluttering the story, a flood of details kills the mystery and the engagement. A good story has a sense of wonder, it raises curiosity, it leaves something untold for us to gnaw on. Perhaps it’s a glance out of frame; we’re familiar with the look of affection she has on her face, but who is she looking at? A face moves into silhouette as you press the shutter, and suddenly a photo of a specific woman is a photo of a woman around whom there is some mystery.

What you leave in the frame must be part of the story. It must be part of the visual plot, even if that’s simply establishing the setting. But you need to be very selective. Leaving a cluttered background by shooting wide & indiscriminately does not establish setting; it’s lazy photography. Each element must be chosen intentionally, even if that occurs intuitively on some level. The more elements within the frame the less power each of them has and your story becomes diluted.

Leave enough clues to tell the story and exclude enough to create a sense of mystery. Unanswered questions engage a viewer and create an interaction between the image and the viewer – a deeper level of viewing that allows us to think and feel more connected to, and touched by, the story.

The choices you make about what to leave in and what to cut out are editorial choices that will determine how clearly the story is told.

“A good story has a sense of wonder, it raises curiosity, it leaves something untold for us to gnaw on.”

Action

Ultimately, story is about change. Something happens, provokes the protagonist to action, which changes things. That’s what conflict is about. The stronger the conflict, the more extreme the action that is provoked, and the greater the change that results. In the still frame a story is often most successfully implied by choosing not only an action but the strongest visual expression of that action. A man throws a baseball. In a video of that action there is a smooth sequence of moves from a wind-up through to a release. In a still frame, we have choices to make. At what point does the throw look most like a throw? At what point is the energy strongest? Does a slower or faster shutter better help communicate the speed of that throw? Does our chosen composition exaggerate that energy or impede it? And then, do we include, if we’re still using the baseball scenario, the batter or the person catching the ball, and thereby include a second element and the possibility of an implied relationship between the two?

Relationships

Relationships of elements to each other within the frame are key compositional tools that give us – or deny us – solid clues as to the unfolding story within the frame.

One object larger than another implies something about the relationship of power between them. The space between two elements or characters within the frame tells something about their connectedness or how they relate to each other. Simply changing your point of view, camera angle or choice of lens can dramatically change the feeling and implied relationship within a photograph.

As an example, using your telephoto lens’ ability to compress space is an excellent way of bringing elements that are distant from each other into a perceived proximity. To go back to the scenario of the baseball pitcher, an image of that pitcher taken with a standard lens, and from the right angle, will show the batter, and the crowds, in the distant background. The same scenario captured with a 200mm lens will compress the foreground and distance and create a stronger implied relationship between the pitcher and the batter, excluding the context of the stadium. In terms of story, one places the main character within his setting, even making a third character of the crowds, the other creates a relationship of closeness and proximity, between the pitcher and batter, as though the two are inseparable, and focuses more on the conflict between them.

If you wanted to show the same pitcher in an even more imposing setting, and show how high the stakes are, you might choose to use a much wider angle lens and get closer to the pitcher. The properties of the wide lens will make the stadium seem more vast, the crowds larger.

Which lens you use will depend on the story you want to tell. In the same way your other choices will be made based on the story you’re telling or the way you want to make your viewer think or feel about the characters/elements within the frame.

What choices you make depend on the story you’re compelled to tell, but being conscious of these tools you use will make your storytelling more intentional and compelling, which in turn will give the reader of your photographs the best shot at feeling what you want them to feel, and experiencing your photograph more deeply.

Story was first published in my Without The Camera column in PHOTOGRAPH magazine, Issue 8. You can get back issues of PHOTOGRAPH, an ad-free and timeless magazine about the art and craft of making photographs here, including 4-issue bundles for $24.

July 5, 2015

OverSharing?

On assignment in Kenya this February. I wasn’t using Instagram, I swear. But I could have been. There are fewer and fewer places I can’t be online and sharing work that’s barely out of the camera.

On assignment in Kenya this February. I wasn’t using Instagram, I swear. But I could have been. There are fewer and fewer places I can’t be online and sharing work that’s barely out of the camera.

A couple years ago I went for sushi with Chase Jarvis and as we sat across the table talking about art and commerce and life and stuff, he expressed an idea that I’ve loved and played with ever since – that the task of an artist is this: to create, and to share, and to do whatever you need to do to sustain that cycle of creating and sharing.

I still love the simplicity of that paradigm. It feels right to me. But lately a couple other conversations have converged and have me wondering, what do we do when the sharing, of which we’re fond, especially online, gets in the way of creating? What do we do when it is sharing itself that sabotages the sustainability of the thing we love? What do we do when looking at the images others share leads to envy, comparisons, discouragement, or worse – imitation – instead of inspiration?

“What do we do when it is sharing itself that sabotages the sustainability of the thing we love?”

I love sharing my work. I love knowing it inspires. I love experiencing the connections with others that it does. And yes, I love the feeling of significance that gets sparked when someone likes or comments or re-tweets. But I do not love those things the way I love the quiet making of a photograph, the private wrestling with the muse that happens while I write a paragraph or a book. I don’t love those accolades the way I love holding a print in my hands the first time and knowing I made this new thing.

And that’s the problem. Those are solo activities. They are things I do on my own, first for myself, and they do not go well when they are tainted with expectations, obligations, and the clamouring of my ego to hurry up and get it out already so others can tell me what they think.

We have never, in all of human history, been able to share our work so immediately and so broadly. There used to be a rhythm to creating and sharing. It took a while to get our work out there. There wasn’t the urgency and the clamour for more that we face now. It took long enough for our work to get around that we had time to create in the lulls. The feedback took longer to return to our ears and we could create without the noise of that feedback distracting us. I wish I could remember who last asked me how I balanced my creative life with my social media life. If you’re reading this, I’m not sure I do. Balance isn’t something I’m known for. But I’ve been giving it a great deal of thought, because I think balance, or something like it, is getting increasingly important for me.

“Would a slower, more considered, more curated, flow of shared images be more sustainable? Perhaps it’s time we slowed down.”

Here are three thoughts I have about sharing my own work – thoughts that I don’t have answers to, but am batting around in my brain.

One. Is it possible that photography has dropped in value / demand as the supply as increased? There is so much incredible photography out there right now, it’s hard to know where to begin assigning value to it. That’s a commercial problem. But is the same not true when we ask people to pay attention instead of money? Would a slower, more considered, more curated, flow of shared images be more sustainable? Perhaps it’s time we slowed down.

Two. Could it be that the interactive nature of social media sharing has more effect on the images I make and the way I make them than I once thought? Would my work be better – or more authentic (and therefore better?) if it was created in isolation from all the thousands of images of others, and without the possibility to so quickly share work that perhaps needs a little more time to mature?More pressing, perhaps: is my ability to share with such immediacy, taking me out of the moment I should be present in, making photographs in, making – most importantly – memories in?

Three. More existentially, would I be happier if I spent less time looking at the heavily curated lifestyles of others? My God, I travel the world, and spend time with nomads, and scuba dive in water Jacques Cousteau counted as the most beautiful in the world, and still I feel the pressure to be like others. How hard might it be for others to resist living a vicarious life instead of living their own?

“More pressing, perhaps: is my ability to share with such immediacy, taking me out of the moment I should be present in, making photographs in, making – most importantly – memories in?”

The issue of sustainability is the most pressing for me right now. I’m considered prolific, but how long can I keep it up? I commented to a friend in Japan that I feel like I’ve created a monster – a beautiful monster, a monster I love – but a monster with a voracious appetite. But I have the time. And I have my entire adult life living as a creative professional so it’s not a new road, and I know ultimately that these are decisions we all need to make on our own. How are others wrestling with this? Have we created a monster we’re now obligated to feed, and watch nervously from the corner of our eyes when we should be making art?

July 1, 2015

Chasing & Drawing

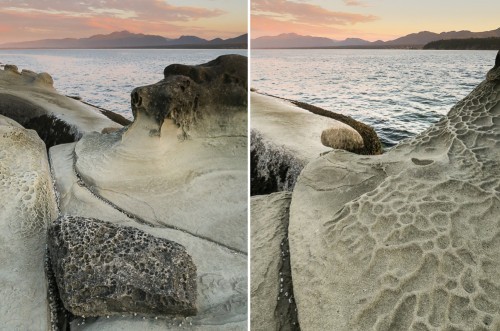

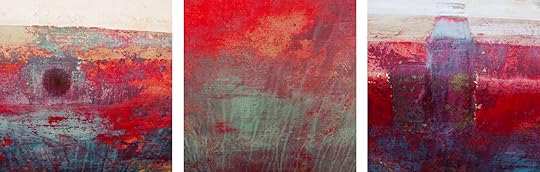

I just got back from 3 days of diving with sea lions in the waters of Hornby Island here in BC. It was easier than I expected to photograph the sea lions because, well, they weren’t there. So that blog post I had planned about how amazing it was to play with, and get chewed by, those amazing puppies of the sea – that’s not going to happen either. We did have an amazing 20-minute encounter with a Giant Pacific Octopus at almost 100 feet, and he crawled all over our cameras. An incredible experience. But photographs? Anything I came home with will probably get post-processed with the CTRL-ALT-DELETE filter. The images above are some sketch images from a location I’m pretty excited to re-shoot when I return to find the sea lions in December.

I’m not frustrated (OK, maybe a little). I think if I’m always learning I’m always growing, and will always have something to teach and the knowledge of what it feels like to climb the learning curve. I feel your pain, people.

There are two things I wish I’d learned earlier as a photographer (actually three – I also wish I’d learned how to be more patient with learning): one is to understand the craft and technique stuff more in terms of aesthetics and less in terms of gear and buttons. I got there eventually. The second is to understand how to draw the eye of the people looking at our photographs. It took years before I ever heard the idea of visual mass – or the pull of various elements in the frame on the eye of the reader. That understanding is simple, but it’s key to composition, storytelling, even some of our post-processing.

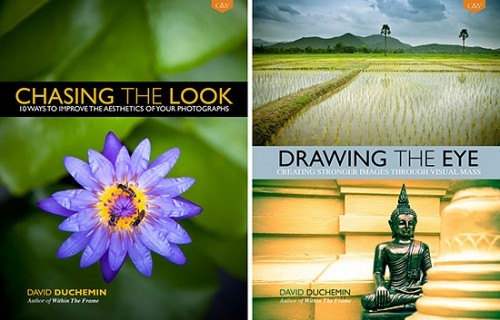

I’m telling you this because while I’ve backed off a lot on promoting Craft & Vision products on my blog – I want you to know that 2 of my earliest eBooks – Chasing the Look, and Drawing the Eye – are on sale for only $2 each, or together for $3.50. It’s a great deal and if you’re newer to my blog and my writing, you may not have heard of these two. One week only. Check them both out.

I also want to thank so many people for putting their names in the hat for the Photoshelter draw. This morning I drew names for Anna VanDenmark, Karen Dean, and Cary Dover. There are emails coming your way. Thanks again to Photoshelter for their support of this community.

June 24, 2015

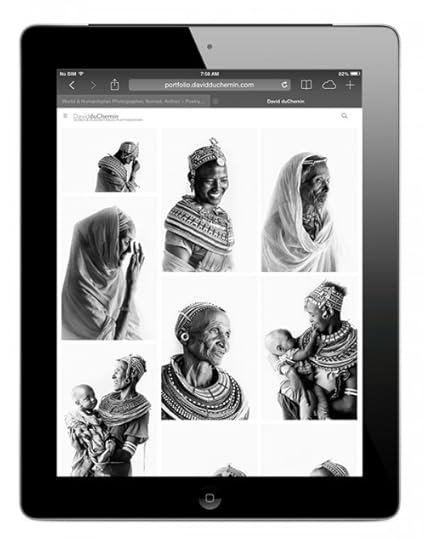

Gimme Shelter – Win a Year with Photoshelter

I doubt I’m the last photographer to get on board with Photoshelter, but I might be close. And if I put it off this long, some of you might have too. I’ve toyed with the idea of looking more deeply into Photoshelter for ages and finally pulled the pin, in part because I want to overhaul my blog and the existing portfolio (like the blog itself) was getting sluggish and was hard to update easily. I resisted Photoshelter for a while because I didn’t like the look of many of the portfolios I saw, but when I dug around under the hood a little I found some templates I really liked. I guess I was just being lazy. About two months ago I made the switch and while I still need to make some edits and tweaks, I’m thrilled with how large the images are, how fast it is, and how well it presents on a multitude of devices.

I doubt I’m the last photographer to get on board with Photoshelter, but I might be close. And if I put it off this long, some of you might have too. I’ve toyed with the idea of looking more deeply into Photoshelter for ages and finally pulled the pin, in part because I want to overhaul my blog and the existing portfolio (like the blog itself) was getting sluggish and was hard to update easily. I resisted Photoshelter for a while because I didn’t like the look of many of the portfolios I saw, but when I dug around under the hood a little I found some templates I really liked. I guess I was just being lazy. About two months ago I made the switch and while I still need to make some edits and tweaks, I’m thrilled with how large the images are, how fast it is, and how well it presents on a multitude of devices.

If you go to the top of my blog you’ll see a PORTFOLIOS link – take it for a spin (or just go here). If you’re looking for a way to update your portfolio, take another look at Photoshelter. They plug the pro features pretty hard, and they’re pretty robust that way (they offer eCommerce and cloud storage, among other things), but for some reason my hang-up was just the aesthetics. I wish I’d dug a little deeper, especially with so many well-known photographers with such beautiful work now using the service.

If you’re still using a Flash portfolio (you know, the kind that no one using an Apple mobile device can view – that’s a lot of us!), or your site needs some loving – take another look at Photoshelter. It’s making my life a lot easier. Faster page loads, easy to update and change, looks great, and they offer some great resources (seriously, check out these fantastic – and free – resources), excellent customer service, and community as well, which I’ve barely had a moment to look at, but features like their Lattice look intriguing. When I have a little more time I’ll also be putting the lion’s share of my best work into the back end of Photoshelter, so I can access – and give access to my clients – from anywhere in the world.

On top of all that, we touched base with them this morning on the off-chance that they’d throw some love at my readers and they’ve agreed to give away 3 standard accounts, free to the winners for a year. All you have to do is leave the usual comments (“I’m in” is fine), make sure you’ve left your name and email address (so we can contact you if you win, not put you on a list) and in a week – on July 01 when I’m back from diving with the Sea Lions off Hornby Island, I’ll draw the winners.

I hope you know me well enough by now to know I don’t pimp stuff I don’t believe in and use myself – there are some great ways to present your work to the world, none of them seemed as easy and robust to me right now as Photoshelter. If you want to test drive it, you can do that for free for 14 days – if you want to try it for longer, look into Photoshelter, then put your name in the comments below (RSS readers, please don’t reply by email – you’ll have to open a browser window and come to the blog itself to do this, sorry).

Huge thanks to Photoshelter for their friendly help and for being so generous to my readers!