Michael J. Behe's Blog, page 565

November 23, 2018

What would a black hole really look like?

black hole/Alain r

If you saw it up close?

If you were to take a photo of a black hole, what you would see would be akin to a dark shadow in the middle of a glowing fog of light. Hence, we called this feature the shadow of a black hole .

Interestingly, the shadow appears larger than you might expect by simply taking the diameter of the event horizon. The reason is simply, that the black hole acts as a giant lens, amplifying itself.

Surrounding the shadow will be a thin ‘photon ring’ due to light circling the black hole almost forever. Further out, you would see more rings of light that arise from near the event horizon, but tend to be concentrated around the black hole shadow due to the lensing effect. Heino Falcke, “Will we ever see a black hole?” at ScienceNordic

Never midn the fact that you would be dead. Details, details. Seriously, astrophysicist Dr. Falcke adds that there are two supermassive black holes relatively near Earth, whose shadows could bde resolved using modern technology:

These are the black holes in the center of our own Milky Way at a distance of 26,000 lightyears with a mass of 4 million times the mass of the sun, and the black hole in the giant elliptical galaxy M87 (Messier 87) with a mass of 3 to 6 billion solar masses.

M87 is a thousand times further away, but also a thousand times more massive and a thousand times larger, so that both objects are expected to have roughly the same shadow diameter projected onto the sky. Heino Falcke, “Will we ever see a black hole?” at ScienceNordic

Wow. That throws a bit of shade even at INSIGHT.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: What Earth vs Mars can teach us about fine tuning It’s hoped that the new INSIGHT spacecraft, due to arrive on Mars on Monday, November 26, will help us understand why life on Mars either never took off or died out.

Black holes do not behave as string theorists say they should

and

In pursuit of the multiverse’s black hole to infinity

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Who’s behind Quillette besides the “intellectual dark web”?

Quillette is one of the publications to which we sometimes direct your attention. It publishes figures who, in many cases, shouldn’t be particularly controversial but are. Along comes Politico to oblige us with an explanation: An Australian atheist feminist and psychology dropout, Claire Lehmann, founded it because she realized that magazines are more fun when people who have studied things seriously are allowed to say what they think:

At times, it has drawn intense social media backlash, with contributors labeled everything from “clowns” to “cryptofascists” on Twitter. But fans of the site include pop psychologist Jordan Peterson, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, psychology professors Steven Pinker of Harvard and Jonathan Haidt of New York University, and columnists like David Brooks, Meghan Daum and Andrew Sullivan. “I continue to be impressed that Quillette publishes heterodox but intellectually serious and non-inflammatory pieces [about] ideas that have become near-taboo in academic and intellectual discourse,” Pinker wrote to me in an email, “including ones connected to heritability, sex and sex differences, race, culture, Islam, free speech and violence.” Haidt, co-author of the recent book The Coddling of the American Mind, called Quillette in an email “a gathering place for people who love to play with ideas and hate being told that there are ideas they are not supposed to play with.”

Curiously, the original group was largely evolutionary psychologists. But Lehman looked beyond the deep dive into the Stone Age to see that, in an academic world increasingly dominated by enraged biddies, male and female, it is tough to discuss any serious ideas. So then where?

Over a 30-day period this fall, Quillette received north of 2 million page views—more than the New York Review of Books, and more than Harper’s and Tablet combined, according to data Lehmann provided from the analytics service Alexa. Twitter, the forum of choice for contrarians, is the site’s biggest driver of traffic. Lehmann herself has more than 100,000 followers, and giants like Peterson and Pinker regularly tweet links to Quillette articles. In June, Peterson, who has encouraged his followers to donate to the site, tweeted, “Quillette gives me hope for the future of journalism.” Amelia Lester, “The Voice of the ‘Intellectual Dark Web’” at Politico Magazine

Apart from publications like Quillette, journalism won’t have a future. The internet provides access to hundreds of same-old publications, free havens of Approved Thought. Only publications offering new or different ideas are worth taking any time to seek out.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: At Quillette: Who will the Evergreen mob (targeted biology teacher recently) target next?

Transgender activism: The war on science is an equal opportunity field

Mortarboard mob “disappears” respected mathematician

and

Bret Weinstein, the Evergreen prof who got SJW-d? It’s partly the fault of creationists!

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Humans “off the hook” for ancient African mammal extinction?

Only five species of massive herbivores are left and some say humans killed off the others:

Writing in the journal Science, Tyler Faith, from the Natural History Museum of Utah, and colleagues argue that long-term environmental change drove the extinctions.

This mainly took the form of an expansion of grasslands, in response to falling atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO ) levels.

“Despite decades of literature asserting that early hominins (human relatives) impacted ancient African faunas, there have been few attempts to actually test this scenario or to explore alternatives,” said Dr Faith. “Humans ‘off the hook’ for African mammal extinction” at BBC

Now that Dr. Faith mentions it, the claim is more of an accusation than a hypothesis, and it is one no living person can easily refute. Except to make the obvious point that humans were not very numerous or powerful back then.

According to the numbers, 28 species of large herbivores went extinct; the decline began about 4.6 million years ago, and evidence for humans is found from about 3 million years ago but there was no change in the pattern as a result.

Of course, if evidence is found for humans earlier than 3 million years ago, it might change the picture.

Abstract: Megaherbivore extinctions in Africa

Human ancestors have been proposed as drivers of extinctions of Africa’s diverse large mammal communities. Faith et al. challenge this view with an analysis of eastern African herbivore communities spanning the past ∼7 million years (see the Perspective by Bobe and Carvalho). Megaherbivores (for example, elephants, rhinos, and hippos) began to decline about 4.6 million years ago, preceding evidence for hominin consumption of animal tissues by more than 1 million years. Instead, megaherbivore decline may have been triggered by declining atmospheric carbon dioxide and expansion of grasslands. (paywall) More.

From Eurekalert,

Faith and his team quantified long-term changes in eastern African megaherbivores using a dataset of more than 100 fossil assemblages spanning the last seven million years. The team also examined independent records of climatic and environmental trends and their effects, specifically global atmospheric CO2, stable carbon isotope records of vegetation structure, and stable carbon isotopes of eastern African fossil herbivore teeth, among others.

Their analysis reveals that over the last seven million years substantial megaherbivore extinctions occurred: 28 lineages became extinct, leading to the present-day communities lacking in large animals. These results highlight the great diversity of ancient megaherbivore communities, with many having far more megaherbivore species than exist today across Africa as a whole.

Further analysis showed that the onset of the megaherbivore decline began roughly 4.6 million years ago, and that the rate of diversity decline did not change following the appearance of Homo erectus, a human ancestor often blamed for the extinctions. Rather, Faith’s team argues that climate is more likely culprit.

“The key factor in the Plio-Pleistocene megaherbivore decline seems to be the expansion of grasslands, which is likely related to a global drop in atmospheric CO2 over the last five million years,” says John Rowan, a postdoctoral scientist from University of Massachusetts Amherst. “Low CO2 levels favor tropical grasses over trees, and as a consequence savannas became less woody and more open through time. We know that many of the extinct megaherbivores fed on woody vegetation, so they seem to disappear alongside their food source.”

The loss of massive herbivores may also account for other extinctions that have also been attributed to ancient hominins. Some scientist suggest that competition with increasingly carnivorous species of Homo led to the demise of numerous carnivores over the last few million years. Faith and his team suggest an alternative.

“We know there are also major extinctions among African carnivores at this time and that some of them, like saber-tooth cats, may have specialized on very large prey, perhaps juvenile elephants” says Paul Koch. “It could be that some of these carnivores disappeared with their megaherbivore prey.”

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: Mystery: Extinct birds as well adapted for flight as surviving modern ones

and

Assumed extinct, tree kangaroo reappears

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

If life might be “programmed into” the laws of nature, why not humans?

From a review of Universe in Creation: A New Understanding of the Big Bang and the Emergence of Life by astrophysicist Roy R. Gould:

From a review of Universe in Creation: A New Understanding of the Big Bang and the Emergence of Life by astrophysicist Roy R. Gould:

Whichever specific origin of life theory we turn to, the thesis that life is somehow programmed into the universe feels uncomfortable but also attractive. Uncomfortable, because it seems to carry a whiff of creationism: Is this just wishful thinking after all, intelligent design gussied up for the scientifically-minded? It is attractive, however, for the same reason. It means that life is the inevitable, invariant consequence of the laws of physics at work, giving life about as much meaning in the universe as an atheist could in good conscience ask for.

What we want to be true is, of course, irrelevant. The fascinating thing, however, is that Gould’s thesis may very well prove true. If it turns out that life—even the most rudimentary microbial life—is common to the universe, the case, as Gould suggests, is settled. Given the distances humans would have to travel to verify this, it is not something that can easily be proved. But even if there is or ever has been any sort of simple life on Mars—and this is something that could be ascertained in our lifetime—then Shapiro and Gould, although they embrace different theories of the origins of life, are essentially correct. After all, if life emerged independently on two planets in a single solar system, it is nothing unusual. Indeed, that finding alone would be powerful evidence that life has a tendency to emerge, and is presumably widespread throughout the universe. The origins of life would indeed be found in the laws of nature.

But we can’t make too much of that either. For though any such finding would greatly raise life’s stature in the universe, it would do nothing to elevate that of humanity. Even if we prove that life is a property of physics, we humans would still be creatures of chance—and natural selection. Monod would thus be half-wrong and half-right: the universe would indeed have been pregnant with life, but not with humanity. Adam Gaffney, “How Did Life Emerge?” at The New Republic

Gaffney’s second conclusion doesn’t really make sense. If we are willing to think it reasonable that life itself is something found in the laws of nature, why might human life not be so as well? For that matter, there could certainly be other intelligent entities in our universe. We just don’t have evidence either way so we can’t assume it must be true.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: Does nature just “naturally” produce life?

And

Can all the numbers for life’s origin just happen to fall into place?

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Logic and First Principles: How could Induction ever work? (Identity and universality in action . . . )

In a day when first principles of reason are at a steep discount, it is unsurprising to see that inductive reasoning is doubted or dismissed in some quarters.

And yet, there is still a huge cultural investment in science, which is generally understood to pivot on inductive reasoning.

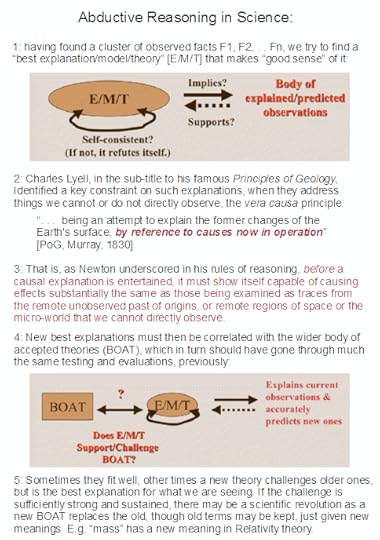

Where, as the Stanford Enc of Phil notes, in the modern sense, Induction ” includes all inferential processes that “expand knowledge in the face of uncertainty” (Holland et al. 1986: 1), including abductive inference.” That is, inductive reasoning is argument by more or less credible but not certain support, especially empirical support.

How could it ever work?

A: Surprise — NOT: by being an application of the principle of (stable) distinct identity. (Which is where all of logic seems to begin!)

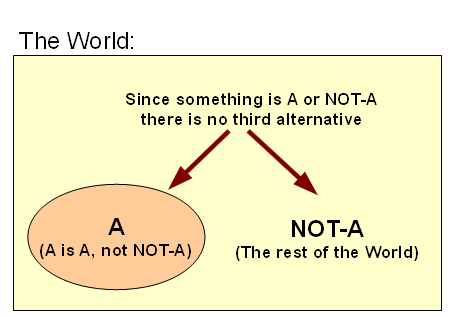

Let’s refresh our thinking, partitioning World W into A and ~A, W = {A|~A}, so that (physically or conceptually) A is A i/l/o its core defining characteristics, and no x in W is A AND also ~A in the same sense and circumstances, likewise any x in W will be A or else ~A, not neither nor both. That is, once a dichotomy of distinct identity occurs, it has consequences:

Laws of logic in action as glorified common-sense first principles of right reason

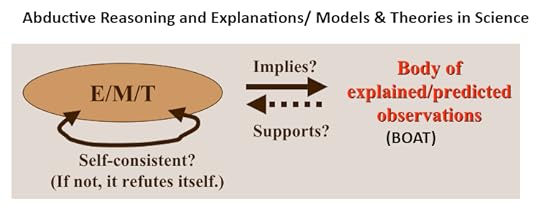

Where also, we see how scientific models and theories tie to the body of observations that are explained or predicted, with reliable explanations joining the body of credible but not utterly certain knowledge:

Abductive, inductive reasoning and the inherent provisionality of scientific theorising

As I argued last time:

>>analogical reasoning [–> which is closely connected to inductive reasoning] “is fundamental to human thought” and analogical arguments reason from certain material and acknowledged similarities (say, g1, g2 . . . gn) between objects of interest, say P and Q to further similarities gp, gp+1 . . . gp+k. Also, observe that analogical argument is here a form of inductive reasoning in the modern sense; by which evidence supports and at critical mass warrants a conclusion as knowledge, but does not entail it with logical necessity.

How can this ever work reliably?

By being an application of the principle of identity.

Where, a given thing, P, is itself in light of core defining characteristics. Where that distinctiveness also embraces commonalities. That is, we see that if P and Q come from a common genus or archetype G, they will share certain common characteristics that belong to entities of type G. Indeed, in computing we here speak of inheritance. Men, mice and whales are all mammals and nurture their young with milk, also being warm-blooded etc. Some mammals lay eggs and some are marsupials, but all are vertebrates, as are fish. Fish and guava trees are based on cells and cells use a common genetic code that has about two dozen dialects. All of these are contingent embodied beings, and are part of a common physical cosmos.

This at once points to how an analogy can be strong (or weak).

For, if G has in it common characteristics {g1, g2 . . . gn, | gp, gp+1 . . . gp+k} then if P and Q instantiate G, despite unique differences they must have to be distinct objects, we can reasonably infer that they will both have the onward characteristics gp, gp+1 . . . gp+k. Of course, this is not a deductive demonstration, at first level it is an invitation to explore and test until we are reasonably, responsibly confident that the inference is reliable. That is the sense in which Darwin reasoned from artificial selection by breeding to natural selection. It works, the onward debate is the limits of selection.>>

Consider the world, in situation S0, where we observe a pattern P. Say, a bright, red painted pendulum swinging in a short arc and having a steady period, even as the swings gradually fade away. (And yes, according to the story, this is where Galileo began.) Would anything be materially different in situation S1, where an otherwise identical bob were bright blue instead? (As in, strip the bob and repaint it.)

“Obviously,” no.

Why “obviously”?

We are intuitively recognising that the colour of paint is not core to the aspect of behaviour we are interested in. A bit more surprising, within reason, the mass of the bob makes little difference to the slight swing case we have in view. Length of suspension does make a difference as would the prevailing gravity field — a pendulum on Mars would have a different period.

Where this points, is that the world has a distinct identity and so we understand that certain things (here comes that archetype G again) will be in common between circumstances Si and Sj. So, we can legitimately reason from P to Q once that obtains. And of course, reliability of behaviour patterns or expectations so far is a part of our observational base.

Avi Sion has an interesting principle of [provisional] uniformity:

>>We might . . . ask – can there be a world without any ‘uniformities’? A world of universal difference, with no two things the same in any respect whatever is unthinkable. Why? Because to so characterize the world would itself be an appeal to uniformity. A uniformly non-uniform world is a contradiction in terms.

Therefore, we must admit some uniformity to exist in the world.

The world need not be uniform throughout, for the principle of uniformity to apply. It suffices that some uniformity occurs. Given this degree of uniformity, however small, we logically can and must talk about generalization and particularization. There happens to be some ‘uniformities’; therefore, we have to take them into consideration in our construction of knowledge. The principle of uniformity is thus not a wacky notion, as Hume seems to imply . . . .

The uniformity principle is not a generalization of generalization; it is not a statement guilty of circularity, as some critics contend. So what is it? Simply this: when we come upon some uniformity in our experience or thought, we may readily assume that uniformity to continue onward until and unless we find some evidence or reason that sets a limit to it. Why? Because in such case the assumption of uniformity already has a basis, whereas the contrary assumption of difference has not or not yet been found to have any. The generalization has some justification; whereas the particularization has none at all, it is an arbitrary assertion.

It cannot be argued that we may equally assume the contrary assumption (i.e. the proposed particularization) on the basis that in past events of induction other contrary assumptions have turned out to be true (i.e. for which experiences or reasons have indeed been adduced) – for the simple reason that such a generalization from diverse past inductions is formally excluded by the fact that we know of many cases [of inferred generalisations; try: “we can make mistakes in inductive generalisation . . . “] that have not been found worthy of particularization to date . . . .

If we follow such sober inductive logic, devoid of irrational acts, we can be confident to have the best available conclusions in the present context of knowledge. We generalize when the facts allow it, and particularize when the facts necessitate it. We do not particularize out of context, or generalize against the evidence or when this would give rise to contradictions . . . [Logical and Spiritual Reflections, BK I Hume’s Problems with Induction, Ch 2 The principle of induction.]>>

So, by strict logic, SOME uniformity must exist in the world, the issue is to confidently identify reliable cases, however provisionally. So, even if it is only that “we can make mistakes in generalisations,” we must rely on inductively identified regularities of the world.Where, this is surprisingly strong, as it is in fact an inductive generalisation. It is also a self-referential claim which brings to bear a whole panoply of logic; as, if it is assumed false, it would in fact have exemplified itself as true. It is an undeniably true claim AND it is arrived at by induction so it shows that induction can lead us to discover conclusions that are undeniably true!

Therefore, at minimum, there must be at least one inductive generalisation which is universally true.

But in fact, the world of Science is a world of so-far successful models, the best of which are reliable enough to put to work in Engineering, on potential risk of being found guilty of tort in court.

Illustrating:

How is such the case? Because, observing the reliability of a principle is itself an observation, which lends confidence in the context of a world that shows a stable identity and a coherent, orderly pattern of behaviour. Or, we may quantify. Suppose an individual observation O1 is 99.9% reliable. Now, multiply observations, each as reliable, the odds that all of these are somehow collectively in a consistent error falls as (1 – p)^n. Convergent, multiplied credibly independent observations are mutually, cumulatively reinforcing, much as how the comparatively short, relatively weak fibres in a rope can be twisted and counter-twisted together to form a long, strong, trustworthy rope.

And yes, this is an analogy.

(If you doubt it, show us why it is not cogent.)

So, we have reason to believe there are uniformities in the world that we may observe in action and credibly albeit provisionally infer to. This is the heart of the sciences.

What about the case of things that are not directly observable, such as the micro-world, historical/forensic events [whodunit?], the remote past of origins?

That is where we are well-advised to rely on the uniformity principle and so also the principle of identity. We would be well-advised to control arbitrary speculation and ideological imposition by insisting that if an event or phenomenon V is to be explained on some cause or process E, the causal mechanism at work C should be something we observe as reliably able to produce the like effect. And yes, this is one of Newton’s Rules.

For relevant example, complex, functionally specific alphanumerical text (language used as messages or as statements of algorithms) has but one known cause, intelligently directed configuration. Where, it can be seen that blind chance and/or mechanical necessity cannot plausibly generate such strings beyond 500 – 1,000 bits of complexity. There just are not enough atoms and time in the observed cosmos to make such a blind needle in haystack search a plausible explanation. The ratio of possible search to possible configurations trends to zero.

So, yes, on its face, DNA in life forms is a sign of intelligently directed configuration as most plausible cause. To overturn this, simply provide a few reliable cases of text of the relevant complexity coming about by blind chance and/or mechanical necessity. Unsurprisingly, random text generation exercises [infinite monkeys theorem] fall far short, giving so far 19 – 24 ASCII characters, far short of the 72 – 143 for the threshold. DNA in the genome is far, far beyond that threshold, by any reasonable measure of functional information content.

Similarly, let us consider the fine tuning challenge.

The laws, parameters and initial circumstances of the cosmos turn out to form a complex mathematical structure, with many factors that seem to be quite specific. Where, mathematics is an exploration of logic model worlds, their structures and quantities. So, we can use the power of computers to “run” alternative cosmologies, with similar laws but varying parameters. Surprise, we seem to be at a deeply isolated operating point for a viable cosmos capable of supporting C-Chemistry, cell-based, aqueous medium, terrestrial planet based life. Equally surprising, our home planet seems to be quire privileged too. And, if we instead posit that there are as yet undiscovered super-laws that force the parameters to a life supporting structure, that then raises the issue, where did such super-laws come from; level-two fine tuning, aka front loading.

From Barnes:

Barnes: “What if we tweaked just two of the fundamental constants? This figure shows what the universe would look like if the strength of the strong nuclear force (which holds atoms together) and the value of the fine-structure constant (which represents the strength of the electromagnetic force between elementary particles) were higher or lower than they are in this universe. The small, white sliver represents where life can use all the complexity of chemistry and the energy of stars. Within that region, the small “x” marks the spot where those constants are set in our own universe.” (HT: New Atlantis)

That is, the fine tuning observation is robust.

There is a lot of information caught up in the relevant configurations, and so we are looking again at functionally specific complex organisation and associated information.

(Yes, I commonly abbreviate: FSCO/I. Pick any reasonable index of configuration-sensitive function and of information tied to such specific functionality, that is a secondary debate, where it is not plausible that say the amount of information in DNA and proteins or in the cluster of cosmological factors is extremely low. FSCO/I is also a robust phenomenon, and we have an Internet full of cases in point multiplied by a world of technology amounting to trillions of cases that show that it has just one commonly observed cause, intelligently directed configuration. AKA, design.)

So, induction is reasonable, it is foundational to a world of science and technology.

It also points to certain features of our world of life and the wider world of the physical cosmos being best explained on design, not blind chance and mechanical necessity.

Those are inductively arrived at inferences, but induction is not to be discarded at whim, and there is a relevant body of evidence.

Going forward, can we start from this? END

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

November 22, 2018

What Earth vs Mars can teach us about fine tuning

We are told that Earth and Mars are like two siblings who have grown apart: “There was a time when their resemblance was uncanny: Both were warm, wet and shrouded in thick atmospheres. But 3 or 4 billion years ago, these two worlds took different paths”:

We are told that Earth and Mars are like two siblings who have grown apart: “There was a time when their resemblance was uncanny: Both were warm, wet and shrouded in thick atmospheres. But 3 or 4 billion years ago, these two worlds took different paths”:

Long ago, Mars stopped changing, while Earth continued to evolve.

Earth developed a kind of geological “conveyer belt” that Mars never had: tectonic plates. When they converge, they can push the crust into the planet. When they move apart, they enable new crust to emerge.

This churning of material brings more than just rock to the surface. Some of life’s most vital ingredients are so-called volatiles, which include water, carbon dioxide and methane. Because they change into gas easily (that’s what makes them volatile), they can be released by tectonic action.

The fact that Mars doesn’t have tectonic plates suggests its crust was never recycled back into the planet’s interior. Could the appearance of life depend on whether tectonic plates are present to churn up volatiles?“What Two Planetary Siblings Can Teach Us About Life” at JPL-NASA News

It’s hoped that the new INSIGHT spacecraft, due to arrive on Mars on Monday, November 26, will help us understand why life on Mars either never took off or died out.

Clearly, when Mars was younger, its internal heat powered the largest volcanoes in the solar system. In addition to spewing lava, these volcanoes brought water and other gases to the surface, cloaking Mars in a thick atmosphere and perhaps even supplying ancient oceans that could have supported life.

But most of Mars’ atmosphere — and its surface water — disappeared billions of years ago, and InSight’s third major experiment aims to help researchers understand why. That requires looking all the way into the center of the planet.

Like Earth, Mars’ once had a magnetic field produced by molten metal churning in a liquid core. And like on Earth, the field protected the planet’s atmosphere from the torrent of charged particles streaming off the sun. But Mars’ magnetic field winked out quickly, exposing the Martian atmosphere to the ravages of the solar wind. Julia Rosen, “Why is Mars so different from Earth? NASA’s InSight mission will dig deep to find answers” at Los Angeles Times

No one knows why but that could change.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: Is Earth’s magnetic core special too, compared to Mars’s?

and

Organic product methane found in soil samples from Mars

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Should we revise evolution theories for the microbes that form so much of an “animal”?

Does the interaction between individual animal and microbes form something greater the sum of each, considered separately?

Vital functions like digestion and immunity were long assumed to be under the purview of individual organisms, as capabilities developed and were refined through evolution by natural selection — the differential survival and reproduction of individuals. But if our bodies are less an autocracy of identical cells and more a coalition of multitudes, how can we explain their evolution?

Some biologists are calling for a radical upgrade of evolutionary theory, arguing that prevailing ideas, developed from the study of bigger, more easily understood organisms, don’t fit nicely into this new world. Others contend that existing theory just needs to be applied more carefully. All agree that the micro and macro worlds are inescapably interdependent, and that biologists must explore the frontier of their interconnections.Jonathan Lambert, “Should Evolution Treat Our Microbes as Part of Us?” at Quanta

Of course, we should but, as one biologist tells Lambert, “It’s safe to say that the microbial revolution has been impactful in that it throws so many of the traditional ideas out, or at least casts them in a new light.” Many might prefer to just change the subject and go on doing things the old way.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: Scientists urge focus on the microbiome

and

The ocean’s microbiome resembles the human gut’s microbia

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Are Angels “Naturalistic”?

One of my main criticisms of methodological naturalism is that the word “naturalism” seems to not have any real content. It merely means “whatever the author wants to include in science” and non-naturalism means “whatever the author doesn’t want to include in science”. This paper by Halvorson is a case in point.

One of the more frustrating parts of talking about methodological naturalism is coming up with a suitable definition of “naturalism”. I discuss this in-depth in this paper. Essentially, most definitions of naturalism are either extremely vague or extremely self-serving. For instance, “testability” is one definition that is often put forward. But, if supernaturalism is true, there is no reason that supernaturalism couldn’t at least in theory be testable. Observability is another, but that is just another way for saying testable.

Hans Halvorson is a philosopher of science who has (accidentally, I believe) shown just how problematic the word “naturalism” is. He wrote a chapter for the Blackwell Companion to Naturalism called “Why Methodological Naturalism?” (free version available here). In the introduction to his paper, he says,

One striking feature of these theories is that they are naturalistic: they don’t mention gods, demons, or any other supernatural beings.

So, his initial mentioning of naturalism is that it excludes all supernatural beings. However, as he goes further, and develops his definition of “naturalism”, he says that,

an entity x is natural just in case x was created by God

So, for Halvorson, “naturalism” applies to anything that isn’t God. This seems to be problematic for his first discussion of naturalism, and what most people consider naturalistic. Are souls naturalistic? Angels? Demons? Well, in case you think I’m reading too much into his words, Halvorson provides a footnote, which says,

Theists might worry that this definition would classify angels as natural entities. My response: so what? As far as I can tell, theism doesn’t need to classify angels as supernatural.

So, while the original point of his paper was to say that methodological naturalism excludes spiritual beings, his actual definition, by his own words, includes them. So what is even the point of having the word “naturalism” if its meaning is so broad? Wouldn’t it be easier to simply say, “science can’t include God”? In that case, ID would be classified under methodological naturalism (Halvorson attempts to counter this, but that will have to wait for another post). In any case, marking one specific entity as something that science can’t touch is also special pleading.

My own definition of “naturalistic” vs “non-naturalistic” is this: both sides of the ball (Stephen Wolfram and Iris van Rooij on the naturalistic side, and myself and Eric Holloway on the non-naturalistic side).

My challenge to naturalists who don’t like my definition is this – come up with one which is similarly operational, matching the intuition, held by individuals on both sides of the divide, and isn’t guilty of special pleading. It’s harder than you think.

So, coming back to Halvorson, we can see that if a philosopher of science, in a paper about naturalism, can’t figure out if angels and demons are naturalistic, then we have a problem with defining naturalism. If we can’t define it, maybe it isn’t actually doing anything for us?

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Nature’s war on sex

From Nature’s editors: “A move to classify people on the basis of anatomy or genetics” should be abandoned.

From Nature’s editors: “A move to classify people on the basis of anatomy or genetics” should be abandoned.

According to a draft memo leaked to The New York Times, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposes to establish a legal definition of whether someone is male or female based solely and immutably on the genitals they are born with. Genetic testing, it says, could be used to resolve any ambiguity about external appearance. The move would make it easier for institutions receiving federal funds, such as universities and health programmes, to discriminate against people on the basis of their gender identity.

The memo claims that processes for deciding the sex on a birth certificate will be “clear, grounded in science, objective and administrable”.

The proposal — on which HHS officials have refused to comment — is a terrible idea that should be killed off. It has no foundation in science and would undo decades of progress on understanding sex — a classification based on internal and external bodily characteristics — and gender, a social construct related to biological differences but also rooted in culture, societal norms and individual behaviour. Worse, it would undermine efforts to reduce discrimination against transgender people and those who do not fall into the binary categories of male or female. The Editors, “US proposal for defining gender has no basis in science” at Nature

Sad. If all the journal’s editors wanted to say is that a few people aren’t happy with the birthday suit nature issued them and that they shouldn’t be considered weird or bad, well, the editors could just say that. Instead, they need to kowtow to a sort of anti-reality crowd, according to which it doesn’t matter at all.

They are probably getting their information from social science. As they acknowledge, half of classic and recent studies failed replication. Ominously, the takeaway from the recent series of hoaxes carefully perpetrated on journals (including the one about how “gender theory harms dogs”) is this: It doesn’t actually matter. Social science not only need not be science, it also need not make sense. It need only pass the loyalty tests required by a current academic mob.

It will be interesting to see how Darwinians react. Their theories depend, of course, on claims about descent, that is, claims about fertile mating. Whatever goes through that narrow defile must make a great deal of difference and whatever doesn’t makes little or no difference. That’s the whole basis of evolutionary psychology.

Some of us think evolutionary psychology is largely nonsense, of course. But our objections turn on the question of how much genetics can explain, over against natural environment and human culture. We can think of more plausible approaches to studying social behaviour in the digital age, for example, than assuming that it was passed on by selfish genes from the Stone Age.

But, to say that “The idea that science can make definitive conclusions about a person’s sex or gender is fundamentally flawed” is ridiculous because most of the time we don’t even need science. The evidence offered by the editorial makes painfully clear that exceptions are actually rare.

But the editors have a metaphorical gun to the head just now, in terms of social justice mobs who haven’t yet turned on each other. The pattern inherited from recent centuries is, the mobs turn on the local elite, then on each other, then (if not stopped) on the public at large. That’s because their war ends up being with reality and none of us can help being a small part of that reality.

Nature is not well positioned to make much headway in dealing with the current war on math, science, and engineering, so there are probably many capitulations in store.

It’s interesting that this story hit the In bin just after a cosmology in crisis story, where the crisis appears to stem from a predilection for “blathering” about a multiverse rather than doing hard math. If other sciences are downstream from physics, we have a source of stasis already. Kowtowing to political correctness will be another source and it may become hard to distinguish the two currents.

If this analysis is correct, expect to see a lot of smoke, noise, and mirrors around minor or questionable moments in science whose main interest is that they bolster some form of Correctness. All the while vast, clear patterns are increasingly off limits and remain unexplored. We shall see.

If this analysis is correct, expect to see a lot of smoke, noise, and mirrors around minor or questionable moments in science whose main interest is that they bolster some form of Correctness. All the while vast, clear patterns are increasingly off limits and remain unexplored. We shall see.

Note: A classic book comes to mind: Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer:

A stevedore on the San Francisco docks in the 1940s, Eric Hoffer wrote philosophical treatises in his spare time while living in the railroad yards. The True Believer — the first and most famous of his books — was made into a bestseller when President Eisenhower cited it during one of the earliest television press conferences.Completely relevant and essential for understanding the world today, The True Believer is a visionary, highly provocative look into the mind of the fanatic and a penetrating study of how an individual becomes one. More.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

See also: Which side will atheists choose in the war on science? They need to re-evaluate their alliance with progressivism, which is doing science no favours.

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

November 21, 2018

Yes, Even Lizards Can Be Smart

If you catch them at the right time. But can we give machines what the lizard has by nature?

If you catch them at the right time. But can we give machines what the lizard has by nature?

We sometimes assume that reptiles cannot be as smart as mammals because they are exothermic (cold-blooded) rather than endothermic (warm-blooded), and the brain is a high metabolic area. Here, though, we find some surprises.

Reptiles lack some brain structures found in mammals but they can use what they’ve got for behavior that we would describe as intelligent: Crocodilians (alligators and crocodiles) have been reported to use sticks as decoys, play, and work in teams.

Exothermy slows intelligence but does not absolutely prevent it: Anole lizards were found as capable as tits (birds) in a problem-solving test for a food reward. But the anoles, being exothermic, don’t need much food — which, of course, hinders research.

Even fish have shown signs of what seems like intelligence… “Yes, Even Lizards Can Be Smart” at Miind Matters

See also: Crows can be as smart as apes

and

Is the octopus a “second genesis” of intelligence?

Copyright © 2018 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Michael J. Behe's Blog

- Michael J. Behe's profile

- 219 followers