Michael J. Behe's Blog, page 418

October 17, 2019

Animal studies tend to show that the human experience is unique

Maybe not what they intended. For example,

For nearly five decades, the mirror test, applied to chimpanzees, was thought to show that they were self-aware:

“In 1970 Gordon G. Gallup, Jr., of the University at Albany, S.U.N.Y., developed the “mirror test” to assess metacognition in chimpanzees. A chimp passes the test if it uses the mirror to inspect a mark that has been painted on its face. Although the majority of chimps pass, some do fail, causing certain scientists to consider the test unreliable.” – Robert O. Duncan, “What Are the Structural Differences in the Brain Between Animals That Are Self-aware and Other Vertebrates?” At Scientific American

But then in 2019, a fish, the cleaner wrasse, passed the mirror test:

When chimpanzees, dolphins, elephants, and magpies passed the test, researchers theorized that these animals, recognized as intelligent, were demonstrating a concept of “self.” Now they are not so sure. Is the cleaner wrasse, which grooms other fish for parasites, really self-aware? Are fish much smarter than we think?

Researchers have begun to question whether the mirror test truly identifies self-awareness.

Intelligence of some type can exist without apparent evidence of self-awareness. An amoeba is smarter than your computer for some purposes, as is a fruit fly but few think it likely that these life forms are self-aware as individuals. “

What do animal studies tell us about human consciousness?” at Mind Matters News

Chimpanzees, dogs, cats, etc., are surely self-aware in the sense that they perceive feelings as experienced by themselves as subjects and events as happening to themselves as subjects. But lacking the ability to reason, they can’t really go beyond that to develop ideas.

Many people assume that human consciousness arose accidentally many eons ago from animal consciousness and that therefore we can find glimmers of the same sort of consciousness in the minds of animals. But that approach isn’t producing the expected results.

See also: Animal minds: In search of the minimal self

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Researchers: Human neurons mature more slowly than those of chimpanzees and macaques

From ScienceDaily:

Since humans diverged from a common ancestor shared with chimpanzees and the other great apes, the human brain has changed dramatically. However, the genetic and developmental processes responsible for this divergence are not understood. Cerebral organoids (brain-like tissues), grown from stem cells in a dish, offer the possibility to study the evolution of early brain development in the laboratory.

Sabina Kanton, Michael James Boyle and Zhisong He, co-first authors of the study, together with Gray Camp, Barbara Treutlein and colleagues analysed human cerebral organoids through their development from stem cells to explore the dynamics of gene expression and regulation (using methods called single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq). The authors also examined chimpanzee and macaque cerebral organoids to understand how organoid development differs in humans. “We observed more pronounced cortical neuron maturation in chimpanzee and macaque organoids compared to human organoids at the same point of development,” said co-senior author Barbara Treutlein. “This would suggest that human neuronal development takes place more slowly than in the other two primates.” Paper. paywall – Sabina Kanton, Michael James Boyle, Zhisong He, Malgorzata Santel, Anne Weigert, Fátima Sanchís-Calleja, Patricia Guijarro, Leila Sidow, Jonas Simon Fleck, Dingding Han, Zhengzong Qian, Michael Heide, Wieland B. Huttner, Philipp Khaitovich, Svante Pääbo, Barbara Treutlein, J. Gray Camp. Organoid single-cell genomic atlas uncovers human-specific features of brain development. Nature, 2019; 574 (7778): 418 DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1654-9 More.

Interesting but not really a surprise because humans mature more slowly generally and live longer. No big news here that accounts for human uniqueness.

See also: What do animal studies tell us about human consciousness? They show that the human experience is unique. Many people assume that human consciousness arose accidentally many eons ago from animal consciousness and that therefore we can find glimmers of the same sort of consciousness in the minds of animals. But that approach isn’t producing the expected results.

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Researcher: The question is not whether epigenetic learning is inherited but how

This longish article is admirably cautious but offers many examples to work with:

One of the outstanding questions in the field is why epigenetic inheritance only lasts for a handful of generations and then stops, said Eric Greer, an epigeneticist at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital who studies the epigenetic inheritance of longevity and fertility in C. elegans. It appears to be a regulated process, in part because the effect persists at the same magnitude from one generation to the next, and then abruptly disappears. Moreover, in a paper published in Cell in 2016, Rechavi and colleagues described dedicated cell machinery and specific genes that control the duration of the epigenetically inherited response. “So it’s an evolved mechanism that likely serves many important functions,” Rechavi said.

But what exactly is adaptive about it? If the response is adaptive, why not hardwire it into the genome, where it could be permanently and reliably inherited?

Viviane Callier, “Inherited Learning? It Happens, but How Is Uncertain” at Quanta

Why do the epigenetic changes last only a few generations? Hmmm. Well, if life, in general, exists by design and not by chance, many adaptations may only be intended to last a few generations. Environments constantly change, after all, and a requirement that all patterns be locked in could be a road to extinction.

See also: Genetic Literacy Project: Most Epigenetic Changes Not Passed On To Offspring

and

Epigenetic change: Lamarck, wake up, you’re wanted in the conference room!

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Templeton is sponsoring a historic type of contest in the quest to understand consciousness

The two theories to be tested pit “information processing” against “causal power” as a model of consciousness. One side must admit it is wrong:

Stanislas Dehaene/Henning (CC-BY-2.0)

Stanislas Dehaene/Henning (CC-BY-2.0) Consciousness, even as a concept, is much more slippery than gravity but these two prominent theories have been chosen as at least suitable for testing, starting this fall:

● Global Workspace Theory (GWT), defended by Stanislas Dehaene of the Collège de France in Paris: “theory of Bernard Joseph Baars that suggests that consciousness involves the global distribution of focal information to many parts of the brain.” – Pam N., “Global Workspace Theory,” Psychology Dictionary

vs.

● Integrated Information Theory (IIT), defended by Giulio Tononi of the University of Wisconsin in Madison: “Initially proposed by Giulio Tononi in 2004, it claims that consciousness is identical to a certain kind of information, the realization of which requires physical, not merely functional, integration, and which can be measured mathematically according to the phi metric.” – Francis Fallon, Integrated Information Theory of Consciousness, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The two theories can be compared because they make different predictions as to which part of the brain will become active when a person becomes aware of an image.

“Quest for consciousness: A historic quest is announced” at Mind Matters News

Giulio Tononi

We are sure that, in reality, anyone really attached to the losing theory will find wiggle room. But never mind. The point is, there is something to test.

This sure beats: Consciousness is an evolved illusion; your coffee mug is conscious; consciousness is a material thing; electrons are conscious No wonder consciousness studies have been described in Chronicle of Higher Education as “bizarre.” Maybe not so much now.

Key concepts in a non-materialist approach to consciousness

An Oxford neuroscientist explains

mind vs. brain (Michael Egnor) Sharon Dirckx explains the fallacies of materialism and the logical and scientific strengths of dualism

Did consciousness “evolve”? (Michael Egnor) One neuroscientist doesn’t seem to understand the problems the idea raises

Four researchers whose work sheds light on the reality of the mind The brain can be cut in half, but the intellect and will cannot, says Michael Egnor. The intellect and will are metaphysically simple

and

No materialist theory of consciousness is plausible (Eric Holloway) All such theories either deny the very thing they are trying to explain, result in absurd scenarios, or end up requiring an immaterial intervention

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

October 16, 2019

Once again, for the thousandth time, we are “closing in” on alien life

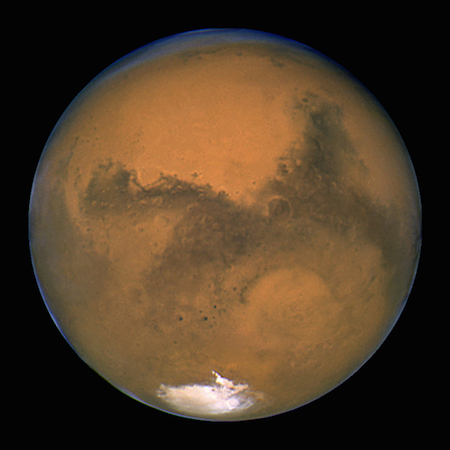

Mars/NASA

Mars/NASA

Here’s an evergreen story for you, courtesy Seth Shostak from Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI):

In the next decade or so, it’s entirely possible that you’ll see a headline announcing that NASA has found evidence of life in space.

Would that news cause you to run screaming into the street? An article that appeared recently in Britain’s Sunday Telegraph hints that Jim Green, the director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, thinks the public might be discombobulated by the discovery of biology beyond the bounds of our own planet. But that’s not really what Green believes. He’s concerned that we haven’t thought much about the next steps by scientists, should we suddenly confront the reality of Martian life.

Seth Shostak, “We may be closing in on the discovery of alien life. Are we prepared?” at NBC News

Actually, if you ask planetary scientist Gil Levin or our experimental physicist color commentator Rob Sheldon, they’ll tell you we’ve already found evidence of fossil bacteria on Mars. Didn’t notice anybody screaming in the streets about it either way though.

Life on Mars would be a lot of fun but one suspects it’ll never live up to the hype.

See also: At Scientific American: We did find life on Mars in the ‘70s. Rob Sheldon weighs in Levin: When the Viking Molecular Analysis Experiment failed to detect organic matter, the essence of life, however, NASA concluded that the LR had found a substance mimicking life, but not life. Inexplicably, over the 43 years since Viking, none of NASA’s subsequent Mars landers has carried a life detection instrument to follow up on these exciting results.

and, for the cultural background,

Tales of an invented god

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Researchers: There is an inference crisis as well as a replication crisis

Admittedly in social sciences, but maybe worth unpacking anyway: From ScienceDaily:

For the past decade, social scientists have been unpacking a “replication crisis” that has revealed how findings of an alarming number of scientific studies are difficult or impossible to repeat. Efforts are underway to improve the reliability of findings, but cognitive psychology researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst say that not enough attention has been paid to the validity of theoretical inferences made from research findings.

Using an example from their own field of memory research, they designed a test for the accuracy of theoretical conclusions made by researchers. The study was spearheaded by associate professor Jeffrey Starns, professor Caren Rotello, and doctoral student Andrea Cataldo, who has now completed her Ph.D. They shared authorship with 27 teams or individual cognitive psychology researchers who volunteered to submit their expert research conclusions for data sets sent to them by the UMass researchers.

“Our results reveal substantial variability in experts’ judgments on the very same data,” the authors state, suggesting a serious inference problem. Details are newly released in the journal Advancing Methods and Practices in Psychological Science…

Rotello adds, “The message here is not that memory researchers are bad, but that this general tool can assess the quality of our inferences in any field. It requires teamwork and openness. It’s tremendously brave what these scientists did, to be publicly wrong. I’m sure it was humbling for many, but if we’re not willing to be wrong we’re not good scientists.” Further, “We’d be stunned if the inference problems that we observed are unique. We assume that other disciplines and research areas are at risk for this problem.” Paper. paywall – Jeffrey J. Starns, Andrea M. Cataldo, Caren M. Rotello, Jeffrey Annis, Andrew Aschenbrenner, Arndt Bröder, Gregory Cox, Amy Criss, Ryan A. Curl, Ian G. Dobbins, John Dunn, Tasnuva Enam, Nathan J. Evans, Simon Farrell, Scott H. Fraundorf, Scott D. Gronlund, Andrew Heathcote, Daniel W. Heck, Jason L. Hicks, Mark J. Huff, David Kellen, Kylie N. Key, Asli Kilic, Karl Christoph Klauer, Kyle R. Kraemer, Fábio P. Leite, Marianne E. Lloyd, Simone Malejka, Alice Mason, Ryan M. McAdoo, Ian M. McDonough, Robert B. Michael, Laura Mickes, Eda Mizrak, David P. Morgan, Shane T. Mueller, Adam Osth, Angus Reynolds, Travis M. Seale-Carlisle, Henrik Singmann, Jennifer F. Sloane, Andrew M. Smith, Gabriel Tillman, Don van Ravenzwaaij, Christoph T. Weidemann, Gary L. Wells, Corey N. White, Jack Wilson. Assessing Theoretical Conclusions With Blinded Inference to Investigate a Potential Inference Crisis. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2019; 251524591986958 DOI: 10.1177/2515245919869583 More.

Abstract: Scientific advances across a range of disciplines hinge on the ability to make inferences about unobservable theoretical entities on the basis of empirical data patterns. Accurate inferences rely on both discovering valid, replicable data patterns and accurately interpreting those patterns in terms of their implications for theoretical constructs. The replication crisis in science has led to widespread efforts to improve the reliability of research findings, but comparatively little attention has been devoted to the validity of inferences based on those findings. Using an example from cognitive psychology, we demonstrate a blinded-inference paradigm for assessing the quality of theoretical inferences from data. Our results reveal substantial variability in experts’ judgments on the very same data, hinting at a possible inference crisis.

In other words, even if social scientists can replicate research results, there may be little agreement about what, if anything, they mean. Is it a good idea for governments to consult them on social policy?

See also: “Motivated reasoning” defacing the social sciences?

At the New York Times: Defending the failures of social science to be science Okay. So if we think that — in principle — such a field is always too infested by politics to be seriously considered a science, we’re “anti-science”? There’s something wrong with preferring to support sciences that aren’t such a laughingstock? Fine. The rest of us will own that and be proud.

What’s wrong with social psychology , in a nutshell

How political bias affects social science research

Stanford Prison Experiment findings a “sham” – but how much of social psychology is legitimate anyway?

A BS detector for the social sciences

All sides agree: progressive politics is strangling social sciences

and

Back to school briefing: Seven myths of social psychology: Many lecture room icons from decades past are looking tarnished now. (That was 2014 and it has gotten worse since.)

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

Rob Sheldon: The quantum effects shown in large molecules may make theories like the multiverse testable

Yesterday, we noted that researchers demonstrated quantum effects in giant molecules, showing that the 2000 atom giants could be in two places at once.

Our physics color commentator Rob Sheldon offers some thoughts on why it matters:

—

The point of this experiment is to test the Copenhagen interpretation of QM that says: “Newtonian physics is for big objects, QM is for small ones.” The question, of course, is “how small is small?” Evidently 25000 Dalton molecules with 2000 atoms (H,C,F,Zn, & S) is still small.

One QM theory variation on Copenhagen called “Continuous Spontaneous Localization” says that classical Newtonian physics arises from QM if an object has many, many modes or states, and when all these states “decohere”, they reduce QM statistics to classical statistics. By measuring a hot stream of molecules with billions of states, this experiment may rule out CSL. If so, it would be the first time an interpretation of QM was actually invalidated, suggesting we have entered a new era of testing theories of the foundations of QM. Perhaps we can soon test the wild theories such as Everett’s Many Worlds interpretation.

—

[image error]

Rob Sheldon is the author of Genesis: The Long Ascent, Vols 1 and 2.

See also: The multiverse is science’s assisted suicide

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

But if homo erectus was just an ordinary dude…

As experts say here…

If you bumped into a Homo erectus in the street you might not recognise them as being very different from you. You’d see a certain “human-ness” in the stance, and his or her size and shape might be similar to yours.

But their face would be flatter, with a more obvious brow. And having a conversation would be hard – his or her language skills would be poor (although they could certainly craft a stone tool or light a fire).

Of course this is entirely hypothetical, as Homo erectus is now extinct. This enigmatic human ancestor probably evolved in Africa more than 2 million years ago, although the timing of their disappearance is less clear.

Ian Moffat, “A snapshot of our mysterious ancestor Homo erectus” at Phys.org

Hmm. At least we can know about the tools and the fire. But, in the context, what does it mean to say “his or her language skills would be poor.” What would that actually mean?

One of the most contentious aspects of Homo erectus is who to include in the species. While many researchers include a wide range of specimens from around the world as Homo erectus, some classify the African and Eurasian specimens as Homo ergaster. Others use the terms Homo erectus senso stricto (ie. in the narrow sense) for the Asian specimens and Homo erectus senso lato (ie. in the broad sense) for all specimens.

This somewhat confusing situation is actually far clearer than the early history of Homo erectus where a wide range of names including Anthropopithecus, Homo leakeyi, Pithecanthropus, Sinanthropus, Meganthropus, and Telanthropus were used. The reason for this complexity is that Homo erectus (whatever you choose to call them) have a comparatively wide range of morphological characteristics making it difficult to decide how much diversity to include within the definition of the species.

Ian Moffat, “A snapshot of our mysterious ancestor Homo erectus” at Phys.org

In short, we don’t know but we can at least invent imposing names.

See also: Can we talk? Language as the business end of consciousness

and

Do racial assumptions prevent recognizing Homo erectus as fully human?

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

New Research on Animal Egg Orientation

When the first cell of an animal—the zygote—divides, it usually has a front end, and a back end, and this orientation will influence how the embryo develops. This orientation is inherited from the egg, where certain gene products are deposited, often at the front end of the egg. These so-called … read more

Copyright © 2019 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.

Plugin by Taragana

October 15, 2019

One in 2000 people may have two copies of a chromosome from one parent

And none from the other. And they may show no abnormalities:

To date, most cases of uniparental disomy—having two copies of a chromosome from either mom or dad, rather than one from each—have been identified in the context of disease, but a new study from researchers at the direct-to-consumer genetics company 23andMe finds that this phenomenon is more common than previously realized and exists in many healthy individuals. The study, published yesterday (October 10) in the American Journal of Human Genetics, suggests that uniparental disomy (UPD) occurs in about one in every 2,000 people.

Jef Akst, “Unbalanced Chromosomal Inheritance More Common than Thought” at The Scientist

Apparently, it’s twice as common as once thought. It’s amazing how much the human genome has learned in recent years.

Michael J. Behe's Blog

- Michael J. Behe's profile

- 219 followers