Michael J. Behe's Blog, page 201

May 9, 2021

At Mind Matters News: Why do some famous materialist scientists hate philosophy?

Massimo Pigliucci

Massimo PigliucciPhilosopher of biology Massimo Pigliucci takes Richard Dawkins to task for that but he might have said the same of Stephen Hawking:

I have never seen eye-to-eye with Dawkins. I think his famous “selfish genes” view of evolution is too narrow. I maintain that his influential concept of memes is nothing but a misleading metaphor.

But over the years the most annoying attitude that Dawkins has displayed, as far as I’m concerned, is his relentless criticism of philosophy, coupled with a hopelessly naive view of science. And this past weekend he’s done it again.

Massimo Pigliucci, “Richard Dawkins writes really silly things about science and philosophy” at Figs in Winter (March 8, 2021)

But wait.

… quantum mechanics shows that the basic particles that make up our universe only have a specific position when we measure them. Yes, the particles really exist. But what we understand about their existence is what we choose to measure. And once we are dealing with choices, we must account for them. That’s when we should start to hear from philosophy.

Philosophy isn’t just butting in. It’s more like this: We won’t make any sense of what we are seeing if we don’t start with some premises. To engage in clear thinking, we must examine them.

News, “Why do some famous materialist scientists hate philosophy?” at Mind Matters News

Takehome: Perhaps some scientists disparage philosophy because they do not like to admit that science starts with choices and choices entail philosophy.

You may also wish to read: In quantum physics, “reality” really is what we choose to observe. Physicist Bruce Gordon argues that idealist philosophy is the best way to make sense of the puzzling world of quantum physics. The quantum eraser experiment shows that there is no reality independent of measurement at the microphysical level. It is created by the measurement itself.

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

L&FP42: is knowledge warranted, credibly true (so, reliable) belief?

It’s time to start delivering on a promise to address “warrant, knowledge, logic and first duties of reason as a cluster,” even at risk of being thought pedantic. Our civilisation is going through a crisis of confidence, down to the roots. If it is to be restored, that is where we have to start, and in the face of rampant hyperskepticism, relativism, subjectivism, emotivism, outright nihilism and irrationality, we need to have confidence regarding knowledge.

Doing my penance, I suppose: these are key issues and so here I stand, in good conscience, I can do no other, God help me.

For a start, from the days of Plato, knowledge has classically been defined as “justified, true belief.” However, in 1963, the late Mr Gettier put the cat in among the pigeons, with Gettier counter-examples; which have since been multiplied. In effect, there are circumstances (and yes, sometimes seemingly contrived, but these are instructive thought exercises) in which someone or a circle may be justified to hold a belief but on taking a wider view such cannot reasonably be held to be a case of knowledge.

As a typical thought exercise, consider a circle of soldiers and sailors on some remote Pacific island, who are eagerly awaiting a tape of a championship match sent out by the usual morale units. They get it, play it and rejoice that team A has won over team B (and the few who thought otherwise have to cough up on their bets to the contrary). Unbeknownst to them, through clerical error, it was last year’s match, which had the same A vs B match-up and more or less the same outcome. They are justified — have a right — to believe, what they believe is so, but somehow the two fail to connect leading to accidental, not reliable arrival at truth.

Knowledge must be built of sterner stuff.

Ever since, epistemology as a discipline, has struggled to rebuild a solid consensus on what knowledge is.

Plantinga weighed in with a multi-volume study, championing warrant, which(as we just noted) is at first defined by bill of requisites. That is, we start with what it must do. So, warrant — this builds on the dictionary/legal/commercial sense of a reliable guarantee of performance “as advertised” — will be whatever reliably converts beliefs we have a right to into knowledge.

The challenge being, to fill in the blank, “Warrant is: __________ .”

Plantinga then summarises, in his third volume:

The question is as old as Plato’s Theaetetus: what is it that distinguishes knowledge from mere true belief? What further quality or quantity must a true belief have, if it is to constitute knowledge? This is one of the main questions of epistemology. (No doubt that is why it is called ‘theory of knowledge’.) Along with nearly all subsequent thinkers, Plato takes it for granted that knowledge is at least true belief: you know a proposition p only if you believe it, and only if it is true. [–> I would soften to credibly, true as we often use knowledge in that softer, defeat-able sense cf Science] But Plato goes on to point out that true belief, while necessary for knowledge, is clearly not sufficient: it is entirely possible to believe something that is true without knowing it . . .

[Skipping over internalism vs externalism, Gettier, blue vs grue or bleen etc etc] Suppose we use the term ‘warrant’ to denote that further quality or quantity (perhaps it comes in degrees), whatever precisely it may be, enough of which distinguishes knowledge from mere true belief. Then our question (the subject of W[arrant and] P[roper] F[unction]): what is warrant?

My suggestion (WPF, chapters 1 and 2) begins with the idea that a belief has warrant only if it is produced by cognitive faculties that are functioning properly, subject to no disorder or dysfunction—construed as including absence of impedance as well as pathology. The notion of proper function is fundamental to our central ways of thinking about knowledge. But that notion is inextricably bound with another: that of a design plan.37

Human beings and their organs are so constructed that there is a way they should work, a way they are supposed to work, a way they work when they work right; this is the way they work when there is no malfunction . . . We needn’t initially take the notions of design plan and way in which a thing is supposed to work to entail conscious design or purpose [–> design, often is naturally evident, e.g. eyes are to see and ears to hear, both, reasonably accurately] . . .

Accordingly, the first element in our conception of warrant (so I say) is that a belief has warrant for someone only if her faculties are functioning properly, are subject to no dysfunction, in producing that belief.39 But that’s not enough.

Many systems of your body, obviously, are designed to work in a certain kind of environment . . . . this is still not enough. It is clearly possible that a belief be produced by cognitive faculties that are functioning properly in an environment for which they were designed, but nonetheless lack warrant; the above two conditions are not sufficient. We think that the purpose or function of our belief-producing faculties is to furnish us with true (or verisimilitudinous) belief. As we saw above in connection with the F&M complaint [= Freud and Marx], however, it is clearly possible that the purpose or function of some belief-producing faculties or mechanisms is the production of beliefs with some other virtue—perhaps that of enabling us to get along in this cold, cruel, threatening world, or of enabling us to survive a dangerous situation or a life-threatening disease.

So we must add that the belief in question is produced by cognitive faculties such that the purpose of those faculties is that of producing true belief.

More exactly, we must add that the portion of the design plan governing the production of the belief in question is aimed at the production of true belief (rather than survival, or psychological comfort, or the possibility of loyalty, or something else) . . . .

[W]hat must be added is that the design plan in question is a good one, one that is successfully aimed at truth, one such that there is a high (objective) probability that a belief produced according to that plan will be true (or nearly true). Put in a nutshell, then, a belief has warrant for a person S only if that belief is produced in S by cognitive faculties functioning properly (subject to no dysfunction) in a cognitive environment [both macro and micro . . . ] that is appropriate for S’s kind of cognitive faculties, according to a design plan that is successfully aimed at truth. We must add, furthermore, that when a belief meets these conditions and does enjoy warrant, the degree of warrant it enjoys depends on the strength of the belief, the firmness with which S holds it. This is intended as an account of the central core of our concept of warrant; there is a penumbral area surrounding the central core where there are many analogical extensions of that central core; and beyond the penumbral area, still another belt of vagueness and imprecision, a host of possible cases and circumstances where there is really no answer to the question whether a given case is or isn’t a case of warrant.41 [Warranted Christian Belief (NY/Oxford: OUP, 2000), pp 153 ff. See onward, Warrant, the Current Debate and Warrant and Proper Function; also, by Plantinga.]

So, we may profitably distinguish [a] Plantinga’s specification (bill of requisites) for warrant and [b] his theory of warrant. The latter, being (for the hard core):

a belief has warrant for a person S only if that belief is produced in S by cognitive faculties functioning properly (subject to no dysfunction) in a cognitive environment [both macro and micro . . . ] that is appropriate for S’s kind of cognitive faculties, according to a design plan that is successfully aimed at truth.

Obviously, warrant comes in degrees, which is just what we need to have. Certain things are known to utterly unchangeable certainty, others are to moral certainty, others for good reason are held to be reasonably reliable though not certain enough to trust when the stakes are high, other things are in doubt as to whether they are knowledge, some things outright fail any responsible test.

That’s why I have taken up and commend a modified form, recognising that what we think is credibly, reliably true today may oftentimes be corrected for cause tomorrow. (Back in High School Chemistry class, I used to imagine a courier arriving at the door to deliver the latest updates to our teacher.)

Yes, I accept that many knowledge claims are defeat-able, so open-ended and provisional.

Indeed, that is part of what distinguishes the prudence and fair-mindedness of sober knowledge claims hard won and held or even stoutly defended in the face of uncertainty and challenge from the false certitude of blind ideologies. Especially, where deductive logical schemes can have no stronger warrant than their underlying axioms and assumptions and where inductive warrant provides support, not utterly certain, incorrigible, absolute demonstration.

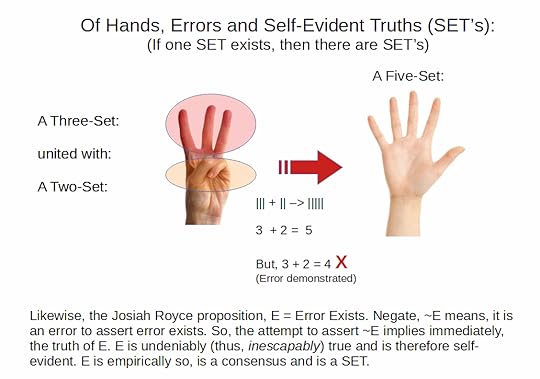

That said, we must recognise that some few things are self-evident, e.g.:

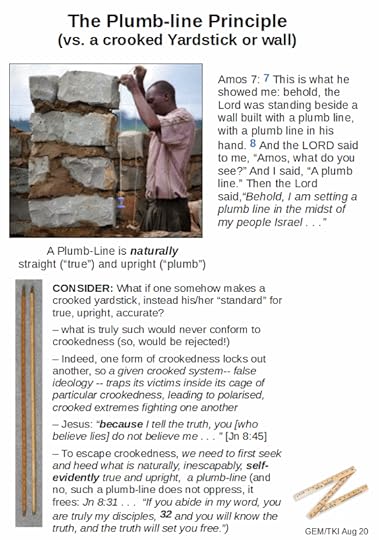

While self-evident truths cannot amount to enough to build a worldview, they can provide plumb line tests relevant to the reliability of warrant for what we accept as knowledge:

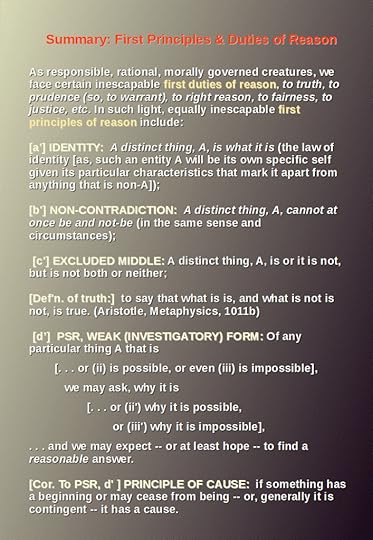

Such, of course, bring to the fore Ciceronian first duties of reason:

Marcus [in de Legibus, introductory remarks, C1 BC, being Cicero himself]: . . . we shall have to explain the true nature of moral justice, which is congenial and correspondent with the true nature of man [–> we are seeing the root vision of natural law, coeval with our humanity] . . . . “Law (say [“many learned men”]) is the highest reason, implanted in nature, which prescribes those things which ought to be done, and forbids the contrary” . . . . They therefore conceive that the voice of conscience is a law, that moral prudence is a law [–> a key remark] , whose operation is to urge us to good actions, and restrain us from evil ones . . . . the origin of justice is to be sought in the divine law of eternal and immutable morality. This indeed is the true energy of nature, the very soul and essence of wisdom, the test of virtue and vice.

We may readily expand such first duties of reason: to truth, to right reason, to prudence, to sound conscience, to neighbour, so also to fairness and justice. Where, it may readily be seen that the would-be objector invariably appeals to the said duties. Does s/he object, false, or doubtfully so, or errors of reason, or failure to warrant, or unfairness or the like, alike, s/he appeals to the very same duties, collapsing in self-referentiality. So, instead, let us acknowledge that these are inescapable, true, self-evident.

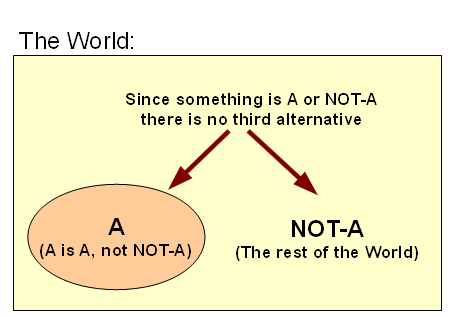

It may help, too to bring out first principles of right reason, such as:

Laws of logic in action as glorified common-sense first principles of right reason

Laws of logic in action as glorified common-sense first principles of right reasonExpanding as a first list:

Such enable us to better use our senses and faculties to build knowledge. END

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

May 8, 2021

Giraffe genome points to maybe four species but it is “not evolutionary”

The genomes of 51 giraffes were studied:

Since humans started classifying species, the iconic giraffe, which roams the savannahs of Africa munching on trees and towering above all other animals, had been considered a single species. With the advent of genetic sequencing, suggestions of six, eight, four and three species of giraffe, with varying numbers of subspecies, have been proposed.

And the debate has been “surprisingly heated,” says Heller. “It’s a problem of life being messy and difficult to pigeonhole, and humans having brains that compulsively put things into pigeonholes,” adds wildlife biologist Derek Lee of Penn State University who did not participate in the study.

Ruth Williams, “Whole-Genome Data Point to Four Species of Giraffe” at The Scientist (May 6, 2021)

And the matter is far from settled. Meanwhile, the giraffe genome will prove a headache for the Darwin Beats Lamarck Punch and Judy Show.

Most summaries of the [giraffe genome] paper, including those in Science magazine and The Scientist, fail to account for the long neck — the very trait that most interested the early evolutionists. Instead, they focus on one particular gene named FGFRL1. In humans and mice, this gene is associated with bone strength and with blood pressure.

The team decided to check what happens when the giraffe version of the gene, with has seven differences from the gene in other mammals, is inserted into mouse embryos. The mice did not grow long necks, but they grew more compact and denser bones. Most importantly, they also survived a drug that raises blood pressure. Giraffe blood pressure is twice that of humans. It appears, therefore, that giraffes have a version of FGFRL1 that protects them from the expected damage to tissues and organs from blood pressure high enough to pump blood up to their lofty 5-meter-high heads. Why is this gene also associated with bone growth?

A few other interesting things were found in the genome: genes related to circadian rhythms that might explain why giraffes get by with little sleep (since getting up off the ground is a “lengthy and awkward procedure”), why their olfactory genes are reduced (“probably related to a radically diluted presence of scents at 5m compared to ground level”), and why their eyesight is so sharp (assumed to be an evolutionary trade-off for less reliance on the sense of smell). The most obvious traits of the giraffe — the long neck, long legs, fur patterns and all — have not been addressed in the paper. The authors admit that “more research on the functional consequences of giraffe-specific genetic variants is needed.”

Evolution News, “Giraffe Genome Is Not Evolutionary” at Evolution News and Science Today (May 7, 2021)

Well, wait. If a big survey of the giraffe genome can’t tell us the answers to the most puzzling questions about one of the most remarkable animals, where should we look for answers next?

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

Forget what you thought you knew about eukaryote evolution…

A radical new scenario for the origine of multicellular life forms is being proposed:

Modern accounts of eukaryogenesis entail an endosymbiotic encounter between an archaeal host and a proteobacterial endosymbiont, with subsequent evolution giving rise to a unicell possessing a single nucleus and mitochondria. The mononucleate state of the last eukaryotic common ancestor, LECA, is seldom, if ever, questioned, even though cells harboring multiple (syncytia, coenocytes, polykaryons) are surprisingly common across eukaryotic supergroups. Here we present a survey of multinucleated forms. Ancestral character state reconstruction for representatives of 106 eukaryotic taxa using 16 different possible roots and supergroup sister relationships, indicate that LECA, in addition to being mitochondriate, sexual, and meiotic, was multinucleate. LECA exhibited closed mitosis, which is the rule for modern syncytial forms, shedding light on the mechanics of its chromosome segregation. A simple mathematical model shows that within LECA’s multinucleate cytosol, relationships among mitochondria and nuclei were neither one-to-one, nor one-to-many, but many-to-many, placing mitonuclear interactions and cytonuclear compatibility at the evolutionary base of eukaryotic cell origin. Within a syncytium, individual nuclei and individual mitochondria function as the initial lower-level evolutionary units of selection, as opposed to individual cells, during eukaryogenesis. Nuclei within a syncytium rescue each other’s lethal mutations, thereby postponing selection for viable nuclei and cytonuclear compatibility to the generation of spores, buffering transitional bottlenecks at eukaryogenesis. The prokaryote-to-eukaryote transition is traditionally thought to have left no intermediates, yet if eukaryogenesis proceeded via a syncytial common ancestor, intermediate forms have persisted to the present throughout the eukaryotic tree as syncytia, but have so far gone unrecognized.

Josip Skejo, Sriram G Garg, Sven B Gould, Michael Hendriksen, Fernando D K Tria, Nico Bremer, Damjan Franjević, Neil W Blackstone, William F Martin, Evidence for a syncytial origin of eukaryotes from ancestral state reconstruction, Genome Biology and Evolution, 2021;, evab096, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evab096

Emphasis added. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) seems to have been pretty complex. So when and where does all that random assembly of vital equipment for life from free-floating chemicals actually happen?

The paper is open access (with a token = URL with a very long tail ).

See also: Researchers: The last bacterial common ancestor had a flagellum Question: If the last common ancestor of the bacterium had a flagellum, what do we really know about the evolution of the flagellum? Isn’t that a bit like finding a stone laptop in a Neanderthal cave? That said, it’s nice to see horizontal gene transfer getting proper recognition.

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

Human exceptionalism: You can be a good or a bad human but you can’t just be an animal

Melanie Challenger, author of How to Be Animal (2021), thinks that human exceptionalism is dead and that we should embrace our true animal nature:

A four-word response to all this: Lord of the Flies

“The novel told the gripping story of a group of adolescent boys stranded on a deserted island after a plane wreck. Lord of the Flies explored the savage side of human nature as the boys, let loose from the constraints of society, brutally turned against one another in the face of an imagined enemy. ”

The wish to escape it all by going “wild” is understandable. But the truth is, we don’t have a “true animal nature.” Animals can’t reason. But humans can’t not reason. We can’t escape knowing both good and evil and the constant struggle between them by becoming more like animals.

When we try to escape into being animals, all that happens is that we reason badly and become bad humans. And the moment we even bring reason into the discussion — well, that’s precisely what human exceptionalism is about!

Denyse O’Leary, “There is no escape from human exceptionalism” at Mind Matters News

You may also wish to read:

The real reason why only human beings speak. Language is a tool for abstract thinking—a necessary tool for abstraction—and humans are the only animals who think abstractly. (Michael Egnor)

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

Conundrum: What if you could make an exact duplicate of yourself?

(In another venue, I (News) review sci-fi shorts on Saturdays. This film seems worth pointing to because it explores the conundrums of the human self. Is a “self” the same thing as an “individual”?)

“The Unboxing Video” offers philosophy as well as dark comedy around the question of what being “oneself” means. A lonely guy, filming himself unboxing his new android replicant, discovers how hard he is to live with when there are two of him. But can he return “himself” to the manufacturer?

For one thing, the replicant doesn’t know that he is not the original. He has no reason to think so:

Immortal line from the replicant: “When I set this whole thing up, I thought it would be someone like me, not actually me.” So James tries to explain to James 1.0 that he is not really “me” and not really “you” either. Soon, he tries out “we.” But, as it turns out, it’s not really “we” either, as the product begins reviewing the purchaser …

News, “Sci-fi Saturday: Why you do NOT want to duplicate yourself” at Mind Matters News

And that does not go well.

You may also wish to read: Are human brain transplants even possible? What would be the outcome if one person received transplants from the brains of others? If it’s not possible, there may be a good reason why not. If tiny bits of the brains from all the people in my neighborhood were transplanted into my brain, would there be a neighborhood in my skull? (Michael Egnor)

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

May 7, 2021

Sabine Hossenfelder on the physics discoveries that make the headlines and then just disappear

Exotic particles that don’t survive a news cycle. She shows how they’re artifacts of the fact that very large numbers often show what appear to be patterns but are just noise:

In summary: Possible reasons why a discovery might disappear are (a) fluctuations (b) miscalculations (c) analysis screw-ups (d) systematics. The most common one, just by looking at history, are fluctuations. And why are there so many fluctuations in particle physics? It’s because they have a lot of data. The more data you have, the more likely you are to find fluctuations that look like signals. That, by the way, is why particle physicists introduced the five sigma standard in the first place. Because otherwise they’d constantly have “discoveries” that disappear.

Sabine Hossenfelder, “Particle Physics Discoveries That Disappeared” at BackRe(Action)

Note: Here’s a lucid article that discusses the general topic of finding phantom patterns in very large numbers:

Computers excel at finding temporary patterns. Which contributes to the replication crisis in science. “Statistical significance” should not be the goal. The goal should be true relationships that endure and can be used with fresh data to make useful predictions.

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

Researchers: The last bacterial common ancestor had a flagellum

The paper at Science seems paywalled but here it is at BioarXiv and here’s a pdf.

We predict that the last bacterial common ancestor was a free-living flagellated, rod-shaped cell featuring a double membrane with a lipopolysaccharide outer layer, a Type III CRISPR-Cas system, Type IV pili, and the ability to sense and respond via chemotaxis.

A rooted phylogeny resolves early bacterial evolution By Gareth A. Coleman, Adrián A. Davín, Tara A. Mahendrarajah, Lénárd L. Szánthó, Anja Spang, Philip Hugenholtz, Gergely J. Szöllősi, Tom A. Williams Science

A friend writes to say that most of the genes needed for flagella are present, including pili & flagella, with 70 gene families found.

Question: If the last common ancestor of the bacterium had a flagellum, what do we really know about the evolution of the flagellum? Isn’t that a bit like finding a stone laptop in a Neanderthal cave?

That said, it’s nice to see horizontal gene transfer getting proper recognition:

The findings, published in the journal Science today, demonstrate how integrating vertical descent and horizontal gene transfer can be used to infer the root of the bacterial tree and the nature of the last bacterial common ancestor.

Just as in plants and animals, the genomes of Bacteria are home to many different genes. However, Bacterial genes are not only inherited vertically from mother to daughter, but are also frequently exchanged horizontally between potentially distant family members. Amongst its many functions, horizontal gene sharing drives the rapid spread of antibiotic resistance amongst pathogenic Bacteria.

The combination of vertical and horizontal ancestry complicates how we think about evolutionary relationships among Bacteria, with the former best represented as a tree and the latter as a network. The team used phylogenetic methods that simultaneously consider the vertical and horizontal transmission of genes and found that, on average, genes travel vertically two-thirds of the time, suggesting that a tree provides a meaningful framework for interpreting bacterial evolution. University of Bristol, “” at Eurekalert

See also: Horizontal gene transfer: Sorry, Darwin, it’s not your evolution any more.

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

At Gizmodo, of all places: A convergent evolution slide show

Featuring six mammals that have body parts we would be more likely to associate with distant life forms:

Mammals have a pretty basic blueprint. Among other things, we give birth to live young, we’re warm-blooded, and, perhaps most obviously, we all have hair. (Yes, even dolphins.) But in the churn of natural selection, some mammals ended up with appendages that look like they should be found on a reptile, bird, or insect. That’s convergent evolution for you: Why should reptiles be the only ones to enjoy the protection of scales, or birds the benefits of webbed feet? This list is comprised of mammals who have clearly been taking pages from other playbooks.

Isaac Schultz, “6 Mammal Body Parts That Look Like They Were Stolen From Other Animals” at Gizmodo

But wait. “Natural selection,” as usually understood, assumes ancestor-descendant relationships. That’s the point of it. If mammals “have clearly been taking pages from other play books,” how exactly, were they able to do so?

Here’s an item from 2015 on the prevalence of convergent evolution: Evolution appears to converge on goals—but in Darwinian terms, is that possible?

And, as I’ve noted before, the welter of data coming back from paleontology, genome mapping, and other studies are changing paleontology from a discipline dependent on grand theories to one more like human history, dependent on identified facts.

A century or so ago, British anatomist St. George Mivart noted that Darwin’s theory of evolution “does not harmonize with closely similar structures of diverse origin” (convergent evolution). There is more evidence for Mivart’s doubts now than ever.

According to current Darwinian evolutionary theory, each gain in information is the result of a great many tiny, modest gains in fitness over millions or billions of years, due to natural selection acting on random mutations. The resulting solutions should then follow inheritance laws, in the sense that the more similar life forms are according to biological classifications, the more similar their genome map should be.

That just did not work out. Different species can have surprisingly similar genes. For example, kangaroos are marsupial mammals, not placentals. Yet their genes are close to humans. Researchers: “We thought they’d be completely scrambled, but they’re not.”

Kangaroos? Shark and human proteins, meanwhile, are also “stunningly similar.” Indeed, sharks are genetically closer to humans than they are to aquarium zebrafish. Researchers: “We were very surprised… “

Sharks? But does all this not raise a serious question? The popular science literature claims that a near identity between the human and chimpanzee genome is irrefutable evidence of common descent. Why then do we hear so little about any of these findings, which muddy the waters? Why are science writers not even curious?

There is also the question of how easily a life form can “evolve” a complex solution to a difficult problem. Birds are said to have evolved ultraviolet vision at least eight times.

Similarly, whether large bird and mammal brains arise from common descent or convergent evolution is actually uncertain. Two distantly related groups of reptiles are thought to have given rise to mammals and birds, both featuring a much higher brain to body weight ratio than in their ancestors. Paleontologist R. Glenn Northcutt writes that the matter is “contentious and unresolved,” because brains rarely fossilize.

It’s not just mammals and birds. Two different species of deadly sea snake, with “separate evolutions,” were found to be identical. Dolphins and insects, we are told, share components of a hearing system.

The smartest invertebrates, the molluscs (including squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish), seem to have evolved brains four times. From one study we learn, “The new findings expand a growing body of evidence that in very different groups of animals — and mammals, for instance — central nervous systems evolved not once, but several times, in parallel.”

Cambridge paleontologist Simon Conway Morris’s Map of Life website provides many other examples of convergence, listing, for example, the convergent evolution of foul smelling plants (“Love me, I stink”), convergence in sex (love-darts), eyes (camera-style eyes in jellyfish), agriculture (in ants) or gliding (in lizards and mammals).

Convergent evolution is evidence that evolution can happen. But the Darwinian model does not seem to be the right one. The life forms appear to be converging on a common goal.

It’s a good thing some science writers are at last becoming curious.

Here’s the starnosed mole, featured in the slideshow and probably the one that reminds one, sort of, of an insect:

See also: Reformed New Scientist: Covering all the ways evolution can happen and treating Darwinism with… a certain caution.

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

Kin selection? The selfish gene? Researchers ponder why animals adopt other species’ orphans

Beliefs about what animals “should do” are often hampered by a lack of common sense reasoning and an outdated evolution theory:

Mulling various theories to account for the evidence, Winder and Shaw conclude,

Attempts have been made to look for “hidden” relationships between helper and recipient, to make altruism “fit” with evolutionary selfishness. Perhaps instead we may just have to accept that humans are not unique in their capacity to care for and help each other.

ISABELLE CATHERINE WINDER, VIVIEN SHAW, “ANIMAL ADOPTIONS MAKE NO EVOLUTIONARY SENSE, SO WHY DO THEY HAPPEN?” AT THE CONVERSATION

Well yes. If we don’t feel a need to affirm kin selection theory or selfish gene theory, maybe we don’t need an explanation — “evolutionary” or otherwise — for animals adopting unrelated animals. Animals think with their feelings, which do not always follow the theory. If whatever they are doing doesn’t kill them or their kind, that’s enough.

But when Winder and Shaw write, “we may just have to accept that humans are not unique in their capacity to care for and help each other,” again, wait.

What makes humans different is that many humans went out and spent decades studying animals and reporting back to the rest of us. So now you are reading about their work. The animals are simply doing what they do and not reporting or reading about it. That, not the feelings part, is the unbridgeable gap. Any theory that states or implies otherwise is in stark conflict with everyday evidence.

Takehome: Human exceptionalism is never more obvious than when humans are offering rational-sounding arguments against it.

Copyright © 2021 Uncommon Descent . This Feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement UNLESS EXPLICIT PERMISSION OTHERWISE HAS BEEN GIVEN. Please contact legal@uncommondescent.com so we can take legal action immediately.Plugin by Taragana

Michael J. Behe's Blog

- Michael J. Behe's profile

- 219 followers