Dan Wells's Blog, page 16

October 25, 2011

Game Review: Conquest of Nerath

Short version: This the game I've been waiting for all my life, and it's awesome.

Long version: I grew up playing wargames, starting with the classics of Risk and Axis & Allies. I played them every chance I got, and devoured each new mutation of the concept; Castle Risk, Fortress America, Samurai Swords, and more. Anything that had a sprawling map, little plastic soldiers, cool powers, and endless strategy would eventually end up on my kitchen table. The pinnacle of this gaming genre, for me, was Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, a massive game with hordes of pieces and reams of special rules spanning the entire inner solar system. The board mapped out not only each planet but their orbits, and part of the strategy was to time your space fleets such that you could attack easily from one planet to another; attack too late, and instead of raining fiery death upon your enemies you'd end up chasing them desperately while their planet rotated harmlessly away from you.

As I grew older I searched for more games that could capture this thrill I felt as a kid. I wanted a game where you could raise an army, control territory, and balance different units' strengths and weaknesses to create a brilliant strategy. The endless variants of Risk inevitably wore out their welcome–it's a fun "entry level" wargame, but you can only play it so many times before it's flaws become too glaring to handle. The trickle of Axis & Allies variants were better, and in some cases brilliant, but their dedication to historical recreation made them too focused for my purposes. I wanted something endlessly variable, not scenario-based. I tried Twilight Imperium and liked a lot of what it did, but I always felt like the game ended right when it got interesting. Runewars is an improvement, but suffers from the same problem. Age of Conan is great, but doesn't have nearly as much combat as a true wargames should have; I still play it, but it sates other interests, and my search for a perfect wargame continues. War of the Ring has the best combination of flavor and game of anyone the wargames I tried, but it's only two players (or four, if teams share armies) and I wanted something bigger.

And then I found Conquest of Nerath. Wizards of the Coast, the company that makes D&D and Magic: The Gathering, decided a year or two ago to branch the D&D license into board games, starting with dungeon games like Castle Ravenloft, which I love. That gave me high hopes for Conquest of Nerath, and somehow the game managed to exceed these expectations. Here's a brief description: the board is a big map of a fantasy world, split into two continents with a central sea and a large island in the middle. There are four kingdoms, each with a variety of cool units (soldiers, wizards, dragons, monsters, etc.) and a deck of personalized cards to help each kingdom feel and play different from the others.

Simply put, this game has everything I've ever wanted in a wargame. Starting placement is fixed, so you get thrown into the action immediately–no "five turns to build up your army before you start fighting" like in Twilight Imperium–and yet the actual gameplay can branch off in any number of directions from there, so you don't feel locked into a scenario like in Axis & Allies. As you conquer you earn money, which you can spend on new units and castles, and the units all have different strengths and weaknesses so you can customize your forces for different situations and strategies. There are air and naval battles, and simple yet effective ways (and tactically important reasons) to transport troops across the water. The decks of cards make each faction unique, and offer a lot of flavor and replayability. There are even heroes and quests and dungeons, which a lot of other wargames have attempted (most notably Runewars and Age of Conan), but Conquest of Nerath manages to integrate them effortlessly into the battle system, bringing new strategies (and cool treasure) into the game. It succeeds through brilliant simplicity where most other games have failed by trying too hard.

There are even multiple ways to win, based on your preferences and how much time you want to spend; the basic game gives you a victory point each time you conquer a territory, allowing you to play a short, medium, or long game simply by adjusting the victory point goal. My group's preferred method is to win by conquering enemy capitals, which takes longer but encourages a more solid balance of attack and defense. You can play a satisfying short game in about 90 minutes–a miracle in the wargame world–or you can fill an evening with hearty long game if that's your preference.

My one and only complaint about the game is its 4-player cap; the game is so fun that I'd love to be able to play it with more of my friends at once, but there's simply no way to add more, even with an expansion. If the worst I can say about a game is that I wish I could play it with more people, that should tell you something. I'll take my recommendation one step further: Conquest of Nerath is the single best addition to my game collection in years. It's simple yet deep, exciting and flavorful, and the culmination of a lifelong quest to scratch exactly the right gaming itch. If you like this style of game, you will love Conquest of

Nerath.

October 19, 2011

Writing the Future

I invented CDs when I was 12.

To be fair, CD technology already existed before that, even if it wasn't very common, and it's not like I invented a working prototype or anything. What I did do was play a lot of roleplaying games.

To be fair, CD technology already existed before that, even if it wasn't very common, and it's not like I invented a working prototype or anything. What I did do was play a lot of roleplaying games.

Stay with me here.

I played a ton of roleplaying games as a kid (and still do). I didn't get into Dungeons & Dragons until college, but I played other, similar games with all sorts of themes and settings, mostly science fiction. In one of them, there was an adventure supplement detailing a force of self-replicating killer robots, which I loved because I'd just read Fred Saberhagen's Berserker series, so I dove in and started making up all kinds of stories about them.

In one such story I wanted the heroes to find a message that one robot had left for another, and I knew it couldn't just be a piece of paper–these were robots, they needed appropriately robotic forms of writing. Never mind that the more practical way for robots to communicate would be wireless transmission; I needed a physical note, so I started to think about what kind of a note a robot would leave. They had incredible sensors and optical magnifiers, so they could see letters that were very small, and they had powerful lasers so they could write on anything, and with incredible precision. What if, instead of paper, they wrote on sheets of metal or plastic, and in letters so small that they couldn't be discerned with the naked eye–so small, in fact, that they would be perceived not as individual letters but as a reflective sheen on the surface of the metal? A human would see it as just a shiny disk, but a machine could read entire libraries stored on it.

Kind of like this.

Sure, I got some details wrong–my disks didn't spin, and they stored the information differently–but that's not the point. The point is that science fiction presaged real technology. This is not a rare thing: science fiction writers have been creating the future since the beginning of the genre. Remember Captain Kirk's communicator? Early cell phone engineers have essentially admitted to basing the flip phone on that design; science fiction created it, and the real world copied it. In this case, the real world has progressed so far that our cool science fiction ideas now seem outdated–flip phones are practically quaint these days.

How about our vocabulary? The website io9 recently did a short post on common scientific terms that originated in science fiction, and a lot of them are downright shocking. Have you ever had a computer virus? You can thank Dave Gerrold for the term, coined in a short story in 1972. How about robotics? Isaac Asimov, 1941. Genetic engineering? Jack Williamson, also 1941. It was a good year for speculative fiction.

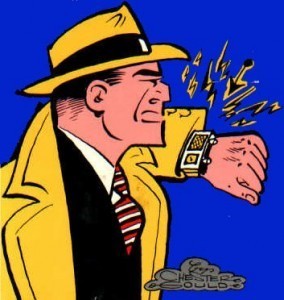

We live in a time where the real world is catching up to science fiction, making the imaginary real at an ever-increasing rate. In Dick Tracy, 80 years ago, Chester Gould posited the two-way wrist radio, eventually followed by full visual communication in the two-way wrist TV; today we have pocket computers so powerful, and so connected, we can do all of this and more. In Ender's Game, 26 years ago, Orson Scott Card predicted a world where politics and social change were played out in a vast web of computer-based essays; today we have blogs and websites so vital to our culture they've basically replaced traditional newspapers. In The Social Network, a mere one year ago, Aaron Sorkin wrote about a world where millions of people connect in a virtual space–and it was nonfiction. We're catching up to our science fictional future, and we're surpassing it.

We live in a time where the real world is catching up to science fiction, making the imaginary real at an ever-increasing rate. In Dick Tracy, 80 years ago, Chester Gould posited the two-way wrist radio, eventually followed by full visual communication in the two-way wrist TV; today we have pocket computers so powerful, and so connected, we can do all of this and more. In Ender's Game, 26 years ago, Orson Scott Card predicted a world where politics and social change were played out in a vast web of computer-based essays; today we have blogs and websites so vital to our culture they've basically replaced traditional newspapers. In The Social Network, a mere one year ago, Aaron Sorkin wrote about a world where millions of people connect in a virtual space–and it was nonfiction. We're catching up to our science fictional future, and we're surpassing it.

Entire books could be written, and many have been, on the impact our science fiction has on our reality. I'm more interested in the process than the effect–the creation of new ideas, new fields of study, and new fictional concepts that will become tomorrow's science. Isaac Asimov was thinking so far ahead of his time, he named an entire branch of now-common engineering. Who's doing that now? Who's extrapolating our current technology so ambitiously that they're presaging and inspiring tomorrow's greatest discoveries? Science fiction is the surest and clearest proof that art not only portrays but creates truth; it blazes new trails for the real world to follow. Who's going to take up that challenge and fire our imaginations?

The first space shuttle was called the Enterprise, explicitly because the engineers who made it and the astronauts who flew it were inspired by Star Trek to a lifelong love of science, discovery, and wonder. That was decades ago; today we are dismantling our space program altogether. We need writers and artists to remind us once more how amazing the future is–to reach out and beckon us onward.

October 13, 2011

Game Review: Battleship Galaxies

I picked up this game because it was designed by Craig Van Ness, the man who designed Heroscape and Heroquest: two excellent games that combined tabletop wargaming and RPG-style dungeon-crawling (respectively) with an easy set of rules. His games are quick, thematic, and easy to learn and play, while still having a surprising amount of depth. Heroscape, for example, is simple enough and "toy-ish" enough to be sold in Walmart and Toys'R'Us, yet strategic and deep enough that I still enjoy it as an adult. Van Ness is a great designer with a solid track record, and I when I found out he was doing a tactical space combat game I was hugely excited.

Space combat games are a weird case, at least for me: I grew up watching Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica, so I want to love space combat games, but I've never actually loved one. Space combat games suffer from a number of sever handicaps, most notably the massive variance of scale (how do you run a Star Destroyer and a TIE fighter in the same rules system?) and the complete lack of terrain in space. This is the biggest problem, in my experience. Tactical combat games are primarily about positioning: you need to get into the right position to have the greatest impact on the battle. In a standard wargame you maneuver around buildings, hide on forests, gain high ground on hills, and so on, but in space you just…shoot the other guy. No position is better or worse than any other position, because you will always have an identical line of sight to your target. Naval wargames have the same problem, which they solve not by adding terrain but by differentiating the specific positioning of the ships: you can come alongside an enemy ship to hit it with more cannons, you can try to get behind a ship to hit its least armored locations, and so on. Some space games do the same, but some try to be so simple (in the interest of easy gameplay) that the game becomes ridiculously boring. There was a Star Wars space combat game a few years ago in which ships had a huge range and nothing blocked line of sight–there was literally no reason to ever move your ship, you just sat there and rolled dice until something blew up.

Battleship Galaxies kind of solves these problems, mostly. That sounds like a weak endorsement, and it is: it's a better space game than any of the others I've tried, but something about it just doesn't do it for me. I don't know what to say. I like it, but I don't love it.

The game has two sides, each with a good mix of big ships, small ships, and fighter squadrons. You build your fleet with a point total, and each ship comes in three different ranks, each with different powers and worth different points, so you have a lot of variety in putting together a team. It even has cards you can play, adding more strategy and an element of deck building. Most of the ships have relatively short ranges, meaning that positioning will be important; I find that I tend to move most of my ships every turn, which is a good sign that something interesting is going on. The exception are the two big capital ships, which have a tendency to just plow down the center of the board and start hammering on people. Even that, though is interesting: some of your ships are blunt instruments, and some are scalpels you need to use more carefully.

Best of all, the game includes terrain tiles and scenarios, giving you something more interesting to do than just sit back and roll dice. Some of the terrain tiles are simple things like asteroids and space junk that you need to maneuver around (or can, in some cases, risk passing through). Other bits of terrain are more complex, providing bonuses for ships that can take and hold them–one, for example, is a shield regenerator, which helps make whatever ship is sitting on it much more survivable. Things like this help make the battlefield dynamic, and offer some cool tactical choices–is it worth heading to the shield generator, or should I just try to kill the other guy before he gets to it? And being a Craig Van Ness game, it accomplishes this measure of strategy in a way that is simple and thematic and fun.

And yet…. I don't know. It's fun without being awesome. If you love space games, or have a kid to play with (my 8yo loves it) it might be worth picking up. I suppose the simplest thing I can say about this game is that I enjoy pulling it out every now and then, but given the opportunity I'd trade it away and not miss it.

October 10, 2011

Deep Space Nine is the best Star Trek series

Over the summer, Netflix added all of the Star Trek series to it's instant service–well, all but one: Deep Space Nine. This made me sad, because DS9 was my favorite, but I figured it would be a good opportunity to catch up on Voyager and Enterprise, which I watched some of (two seasons and one season, respectively) but never really got into. I tried, and quickly remembered why I'd stopped watching those shows (Neelix and implausibility, respectively). I was already in a Star Trek mood, though, so I went back and started watching The Next Generation. I really enjoyed this series while it was on TV–it's final season ended my senior year of high school, and my friends and I were all Star Trek nerds–and in rewatching some of the old episodes I was delighted to see that they held up over time. It wasn't just nostalgia that made me like them in high school, and in fact many of the episodes I remember as kind of boring turned out to be pretty great once I watched them with a more discerning eye.

Last night, having just watched "Pen Pals" from season two (specifically because it was recently covered in Tor.com's TNG rewatch), I decided on a whim to do a search for DS9, just in case Netflix had added it to the Instant Streaming options. TNG is great and all, but the episodic nature of it was really starting to get to me. I wanted the depth of an ongoing story, and the darkness and tension of DS9′s murky political minefield. What could it hurt? I pulled up the search window and…it was there! My sweet, precious Deep Space Nine! I went straight toward the end of season two, when the long-form story just starts to get going (a two-parter about the formation of the Maquis, a resistance/terrorist organization) and started watching.

I love this show so much. We start that episode by watching someone plant a bomb, and then instead of watching it explode, we jump to the control room and listen to Dax and Kira have a snarky, half-friendly-half antagonistic conversation about dating. Not only does this serve as a perfect example of the Hitchcock Principle ("Suspense is when you know there's a bomb but it doesn't go off"), its wonderful character development, and nicely humorous. Then the bomb goes off and a ship explodes, and the entire sequence is a perfect, representative slice of DS9: darkness, conspiracy, humor, character, and mundane life. These characters didn't have time to catalog anomalies and dork around with the Prime Directive, because people were setting bombs on their ships. It was all they could do to keep their heads above water while the darker forces of the universe did everything it could to destroy them. And in the midst of it all they do their best to live a normal life.

The first two seasons of Deep Space Nine were still trying, albeit half-heartedly, to mimic a normal Star Trek show; you still got a lot of political stuff (I can't even count the number of people I've talked to who hate the show based solely on its early preoccupation with Bajoran politics), but there was a lot of "Anomaly of the Week" type stuff. I'm not saying that the other Trek shows were frivolous–they're well-known and well-loved precisely because they deal with weighty issues like ethics and responsibility. The difference with DS9 came in its tone, which was dark and tense and far more bleak than the others. Every Trek show has tricky questions, but DS9 has questions with no good answers–and, more importantly, consequences that come back to haunt the characters for years.

The TNG episode "Pen Pals" is a great example. Data accidentally contacts a young girl on a dying planet, resulting in a fascinating quandary over the Prime Directive: do they save her? Do they save her planet? If saving her will irrevocably destroy her culture, is it still worth it? If the only other option is death, does the Prime Directive even matter? They wrestle with this back and forth for an hour, and it's great science fiction, and then in the end they choose to save her planet and–here's the kicker–wipe the girl's memory. They broke the Prime Directive by directly interfering with a developing culture, and then there were zero consequences, and then they flew away and never thought about it again. All of their deep, philosophical theorizing was interesting, but ultimately meaningless.

Deep Space Nine doesn't have that kind of crap. If they mess with something and cause a problem, they'll have to deal with it, probably several times. They're a space station, so they can't just fly away to a part of space they haven't ruined yet. The Maquis I mentioned earlier were a resistance group forged by the events of a TNG episode: the Federation came to a political agreement with the Cardassians, resulting in a demilitarized zone that displaced a lot of people. Colonists in Federation territory suddenly found themselves, and the homes they'd given so much to build, under enemy control. TNG never really dealt with this, but DS9 used it all the time. The colonists felt betrayed, and when the Cardassians exercised what the colonists considered to be unfair control, they formed a resistance movement and/or terrorist organization. They blew stuff up and killed people, and the DS9 characters couldn't just wipe anyone's memorizes or reroute power to the deflector array, they had to hang around and deal with it and try to make peace in an impossible situation.

In season three, Deep Space Nine embraced its long-form nature and went whole hog, starting a massive war that consumed not only the Federation and the Cardassians, but the Klingons, Romulans, and a new alien nation called the Dominion. The one where the Romulans join the war is one of the best episodes ever: the Federation is losing the war and needs more help, so they order DS9′s captain to enlist the Romulan's help as allies through "any means necessary". If he doesn't get their help, the Federation will be destroyed–but the only way to get their help is to break his own set of ethics in a profound and terrifying way. There are no easy answers on DS9, and the implications of his decisions in that episode haunt him forever.

I don't know why I'm telling you all of this–I can't convince you, objectively, that a piece of art is "good." It's on Netflix now, so watch it for yourself. Perhaps it would be simpler to say that DS9 has my favorite characters of any Star Trek show and leave it at that. Perhaps it's enough to point out that DS9 was run, in part, but Ronald Fracking Moore, who also ran the reimagined Battlestar Galactica. Whatever convinces you totry it, try it. It's my favorite Star Trek show ever.

(And that makes it the best.)

October 3, 2011

Game Review: Nightfall

How many of you have played Dominion? Probably a lot: it's one of those games that managed to break out of the hobbyist crowd and become a well-known party favorite. I'm amazed at the number of people (and, frankly, the variety of people) who've played it. Part of the reason it's successful is that it created an entirely new genre of game, one that had never existed before in any form: the deck-building game. Just like Magic: The Gathering revolutionized the game industry by creating the "collectible card game," a card game where you make your own deck before you play, Dominion revolutionized it seventeen years later by turning the very act of deck-building into the game itself. You start with some basic cards and slowly add more to your deck, reshuffling as necessary, building your own custom deck according to your own strategy. It's a fascinating concept.

Just as with Magic, Dominion has spawned a massive wave of imitators, which is what brings us to Nightfall. Dominion deserves a lot of credit for coming up with the new idea, but Nightfall is the game that finally, for me, made it work. Nightfall's designers were able to look at the other games of this type and identify some key problems, such as lack of player interaction, and address them head-on. A lot of deck-building games feel like multi-player solitaire, which decks that are efficiently designed to accrue more cards and earn more points, but that never interact with each other in meaningful ways. Yes, you get some interaction here and there with "oh no, he's buying a lot of X, I'd better buy some before it's gone," but be honest with yourselves: that's the most boring kind of player interaction possible. In Nightfall you are attacking each other with hordes of vicious monsters, scratching and biting and burning your way to victory; the winner is the player who manages to take the least amount of damage.

(Let me preemptively answer the inevitable retorts of the Dominion fans in the audience: yes, you love it, and yes, the expansions solve some of the issues I mention above, and yes, I still like Nightfall better. You're welcome to play and enjoy any game you want, and me liking Nightfall more doesn't make Dominion bad. Please give Nightfall a try, though, and I think you'll really like it.)

The story behind Nightfall is delightfully bloodthirsty: the world is full of secret cabals of vampires, werewolves, zombies, and ghouls, and the paramilitary teams who hunt them. You start with some basic representatives of each, and use your growing influence to hire more to your cause, carving out a position of power in the urban fantasy underworld. These "starter" cards remove themselves from your deck as soon as you use them, ensuring after a few rounds that your deck is all good stuff–and more specifically, that it's all YOUR stuff, the characters and actions you've personally chosen to put into it.

And I haven't even talked about the best part yet! Half of the player interaction comes from the attack system, and the rest comes from the game's biggest innovation: the chain system. Each card has three colors: a base color and two chain colors. When you play a card, you–or the next player in order–can play another card if it's base color matches one of the chain colors on the previous card. You lay out ever card that people want play, resulting in a chain that could have anywhere from one to a couple dozen cards, and then you resolve them in reverse order. This is a pretty simple system, but it allows for a lot of interaction in a lot of unique ways. Let's say the player on your right is buying a lot of card X–all of a sudden you have a choice to make. Do you buy more of card X for yourself before they're all gone (Dominion style)? Or do you buy more of card Y, because it will chain off of card X? Maybe the best answer is to buy more of card Z, because it counters card X; you have a ton of options, but the point is that you have to pay attention to what your opponents are doing. Add in kicker effects, which are special abilities than only trigger when chained off of very specific color combinations, and the system gets really interesting.

One of the other things I love about the game is the drafting system. At the beginning of the game, as with most deck-building games, you add a limited number of card types to the center of the table. This helps make each game unique, because the card pool is different everytime, which in turn makes the overall game more replayable. With Nightfall this card pool isn't random–you draft it, giving each player their own unique card pool, plus a bit of control over what is and isn't in the overall card pool. It's a fun mechanic which, honestly, could be adapted just as easily to most other deck-building games, but which has even more impact here thanks to the chain system.

If you like deck-building games, Nightfall is a wonderful refinement of the concept that feels like a breath of fresh air in the genre. If you like games in general, or even if you just like vampires and werewolves tearing each other apart, Nightfall is a great choice. There's already one expansion, called Martial Law, and there's another one coming out this fall called Blood Country. And yes, even though it wasn't on my list from last week, I'm totally buying it–I like the game so much that it never occurred to me to NOT buy it, so I didn't think about it for my list. Maybe that's the best recommendation of all.

September 29, 2011

One week from today

One week from today is October 6, and you've got some big events to stick in your calendar.

Number one: I will be the keynote speaker at the UVU Book Festival. I'm speaking at 9am on the subject of "Where do you not get your ideas?" My basic premise is that ideas are easy to come by, and the tricky part is turning them into stories–which I will then explain how to do. The Festival costs 50 bucks, which is a pretty good deal for all the awesome writing instruction you're going to get, so if you're in the area come on down.

Number two: my brother's book, an awesome SF thriller about a mysterious boarding school, comes out that day. The title is VARIANT, and the launch party will be that very same night, October 6, at 7pm at The King's English bookstore in SLC. Rob will do a reading, we'll have some cool giveaways, and you will love it. Trust me, and I'm not just saying this because he's my brother: you REALLY want to read this book.

October 6 is going to be a big day, and you only have one week. Mark your calendars now.

September 28, 2011

Dear Game Companies: Maybe we need to see other people for a while

I love games. Not so much video games, though I do play them occasionally. I'm talking about boardgames and card games; the kind of games where you read a rulebook and sit down with your friends and move little thingies around on a table. I LOVE them. And I am buying too many of them, and I need to stop.

Let's take a look at the list. In the past few months I have acquired Nightfall, Battleship: Galaxies, Conquest of Nerath, Rune Age, Gears of War, Ikusa, and Star Trek: Fleet Captains. Over the next three months I am eagerly looking forward to Mage Knight, Legend of Drizzt, Risk Legacy, and Civilization: Fame and Fortune, and that's after winnowing the list down to a still-not-necessarily-manageable size (I cut out all the Conflict of Heroes games, for example, and two different Napoleonic wargames). Dear game companies: I realize that I'm probably single-handedly propping up your industry with my addiction, but I need to take a breather. Can you please stop making awesome stuff? I barely have time to play the ones I have.

I'll be reviewing all of these games over the next few days, because I love you so much, but first let's talk about the ones I'm not buying. This week sees the release of two new sets of incredibly popular collectible games–both games that I love–and I have made the painful decision to not buy into either one of them. The first is HeroClix, a superhero-themed minis game (ie, "toy soldiers"), which is releasing a new set with a Superman theme–all of Superman's greatest allies and enemies, together in one set. There are a few figures in this set that I'd like to have, but nothing that I need, so I'm just saying no altogether. I'm not a Marvel-is-better-than-DC guy; Green Lantern is my favorite superhero, and the new Wonder Woman comic is one of the best I've ever read. I just have no real interest in this set for some reason. The Legion of Superheroes figures look cool, though, so maybe I'll–no. I will be strong. No more HeroClix until December, when the Hulk set comes out, and I'll have to make another very painful decision.

The other collectible game I've been looking at is the mother of them all, Magic: The Gathering, which I like a lot but haven't played in a long time. They just released their new set, called Innistrad, which has a gothic horror theme that I absolutely love. The art is evocative and gorgeous, the monsters are spooky, the villagers are terrified–how could I not try it out? So I went to a prerelease and tried it out, and…I don't know. It didn't work for me. It's the same old Magic, which is good and bad; the new theme just didn't come across in the gameplay. If I want to play a horror game I have Nightfall, Mansions of Madness, Betrayal at House on the Hill, Last Night on Earth, and so on. If I want to play a game of Magic with some horror tropes pasted on, Innistrad is an option, and I know that if I invested a ton in it I could build a really meaty theme deck about werewolves or possessed children or whatever, but for now I'm going to stay away. I have to make some choices, and Innistrad doesn't make the cut. (I may change that tune when the next set comes out and develops the theme further, but we'll see. I doubt it.)

There are many, many games that I want, but I trimmed the fat and kept only the absolutely coolest, must-have games on my "get this" list. Mage Knight is ostensibly based on an old fantasy minis game by WizKids, the same people who make HeroClix, but the new one is a boardgame far removed from both the mechanics and the flavor. What makes it so appealing is that it's designed by Vlaada Chvatil, a Czech game designer who combines the "efficient use of resources" mentality of European games with the "dragons and robots beating each other up" mentality of American games. In Mage Knight he combines fantasy questing with territory control, sprinkled with a bit of deck-building (the gaming world's hot new thing), used in what appears to be a very cool and clever system. I desperately want it, but I have yet to convince myself that I need it, no matter how clever it looks. I have quest games and army games and deck-building games a-plenty, and I don't think I need any more. That said, it's still on my "get this" list for now.

Legend of Drizzt is a dungeon-crawler in the same series as Castle Ravenloft and Wrath of Ashardalon, which I have praised effusively in the past. They're very simple, even slightly abstracted, takes on dungeon delving, with cooperative mechanics based on 4th Edition D&D and a very slick monster automation system that scales well for different numbers of players. The games are simple and fun, perfectly filling the slot between "I want to play a fantasy adventure" and "I don't have time for a big game." Legend of Drizzt is exciting because, well, it has Drizzt, and Wulfgar, and Artemis Entreri, and all the other characters I know and love from the Bob Salvatore books. How could I not get this game?

Civilization: Fame and Fortune isn't really a full game, it's an expansion for the board game version of Civilization. It will add new nations, new mechanics, new map tiles, and most importantly a new player, bringing the total to five. I realize that I shouldn't be complaining about this, because some people have no game group at all, but my game group is so big and active that we rarely ever get a four-player game on the table. Five is still problematic, but the game is a lot of fun and this will help us play it more often. Hooray!

The final game on the list is the weirdest, and the one I'm most excited about, and the one that if you'd told me a month ago I'd be excited about it I'd have slapped your dirty mouth. Risk, despite the fact that pretty much everyone in the world has played it, is a horrible, horrible game: the balance is off, the mechanics are silly, and meaningful strategy is virtually impossible. There have been a few versions I enjoy, such as Godstorm and 2210, but none of them stand high enough in their category to overshadow something like Conquest of Nerath or even Rune Wars. I never play Risk because there is always, invariably, something more interesting to play instead. So how could someone make me excited to play it again? By adding what is essentially a world-shaping campaign mode. Risk Legacy, due sometime in December, has the most brilliant gaming concept I've heard of in ages: physically altering the board, and the game itself, as you play it. Do you build a city in a certain space? Then you get to name it, and every time you play on that board that city will be there–until someone destroys it. Continents will be named by their conquerors; battles both glorious and horrific will be remembered by later generations; rules will change and grow as the game world goes on, and your battles will affect not just the current game but every game thereafter. You are creating, then, a literal legacy each time you play the game. Lots of boardgames have campaign modes (though not nearly enough of them), but I've never seen this type of thing reflected so extensively. It's an almost sinful idea, writing on the gameboard and ripping up the cards, but that's part of the allure. A game that never resets itself, where your decisions can never be unmade. I'm fascinated. I'll probably buy multiple copies of this one, because that's the kind of innovation I love to support.

So now you know what I'll be spending my money on and/or getting for Christmas. What about those seven games I listed first, the ones I've already played? Watch this space, and I'll review them all.

September 26, 2011

Sleeping Beauty in the Rye, a tale of #BannedBooksWeek

This week is Banned Books Week, a time for us to look back on our long history of closed-minded foolishness and wonder, among other things, what kind of person would ban Charlotte's Web. Someone who hates spiders? Or maybe someone who loves spiders and doesn't want to see them die in fiction? Or maybe it was someone who loves bacon, and thinks the gross depiction of humans not eating a pig was too terrible to inflict on our young readers. Those are honestly my three best guesses; if you're a crazy person espousing another reason I haven't thought of, please let me know because I'm very curious.

Beyond the smaller issue of why someone would ban Charlotte's Web (which is honestly, despite my jokes, one of the most frequently banned books in the US), is the much larger issue of why someone would ban any book at all. I assume that fear is the biggest reason, when you get down to it: fear that someone, most likely an impressionable child, will read a certain book and take from it an idea you perceive as dangerous, either to their personal well-being or to society as a whole. Catcher in the Rye, for example, is banned in part for language, and in part for two separate scenes of almost-sex: one where the narrator hires, talks to, and eventually sends away a prostitute, and another where he is nearly (but not quite) molested by a teacher. Shocking circumstances, certainly, but overall pretty amazingly tame when you think about it. Would you want your child to read a book about a boy who almost gets molested? Not really. But think about it this way: would you want your child to read a book about a boy who recognizes a dangerous situation, confronts the molester, and responds appropriately by leaving immediately? Hell yes. That's EXACTLY the kind of thing I want my children to read. Don't take that away from them.

Let's take a look at what I consider to be the greatest metaphor of sexual education ever told; you know it as Sleeping Beauty. A girl is born and someone tells her parents "You better be careful, because when she hits puberty she's going to be confronted by a situation that could alter and maybe even destroy her life." Her parents have two choices: teach her how to handle that situation, or hide it from her and pretend like it doesn't exist. They choose the latter, but inevitably the child encounters the situation anyway–you can't pretend forever, and sooner or later the bad stuff is going to happen. The poor girl has no idea what this thing is, or what it's for, or how to use it, and it's no surprise to anyone when she immediately uses it wrong. Her life is ruined, and the warning comes true, not because the person who made the warning placed a curse on her, but because the girl's parents failed to prepare her for the realities they knew she would eventually have to face. And then fairies come in and solve everything.

Imagine how differently the story of Sleeping Beauty would be if her parents had just cowboyed up and done their job: "Hey there, daughter, this is a spinning wheel. It's an integral part of our life and culture, and you're going to have to use it one day, but it can be pretty dangerous if you use it wrong. Have a seat and let me explain everything you need to know so you can be safe." Her parents CANNOT protect her from everything, it's literally impossible, but now she has the knowledge and the tools she needs to protect herself.

This is the part where you either agree with my metaphor or find some nit-picky fault with it, such as "parental intervention isn't the same as not banning books." Granted. The simple act of not banning a book is equal, in this case, to not hiding the spinning wheels. All that's going to accomplish is to expose Sleeping Beauty to the danger much earlier and more frequently. What makes the system work, and what makes Sleeping Beauty safe, is when you, the parents, take the time to teach and explain and talk. "This is what a spinning wheel is, this is why it's good, this is why it's bad, and this is how you can use it safely." That last part about using it safely can be anything you personally believe in, anywhere from "I don't care, go crazy" to "make sure you wear some protection" to "Complete and total abstinence from spinning wheels until you're married." I'm not trying to promote a specific agenda here, I'm trying to get parents to take an active hand in teaching their children. Hiding the truth, and hiding from the truth, is not going to work. It never has. If you ban a book to protect your children, sooner or later they're going to encounter exactly what you're afraid of anyway, and they won't be ready for it, and there won't be any fairies around to save the day. You have to do it yourself.

Maybe you have more objections. Maybe you say that you can teach your children about the world just fine without JD Salinger's help, thank you very much. That's fine, I'm sure you can, but that doesn't give you the right to take that opportunity away from anybody else. I don't want you to control what my children read any more than you want me to control what your children read. If you, as a parent, decide that your children shouldn't read Catcher in the Rye, more power to you. You know them better than I do, and I'm delighted you're taking an active hand in their education. But if you, as a concerned neighbor, decide that NOBODY should read Catcher in the Rye, screw you. You don't get to make that decision for my kids, or for me, or for anybody else, no matter how much smarter/holier/worthier you think you are.

I'm not trying to say that every banned book is an educational wonderland of upstanding moral fortitude. Sometimes a book is just nasty, and believe me, I've read a few of them, but I still don't want to ban them, because that's not my decision to make. If everyone has the freedom to explore their own media and make their own decisions, then instead of a lazy, ignorant community that lets other people think for them, suddenly we have a well-read, well-informed community of literate decision-makers, who have not only the freedom but the experience necessary to analyze their media, judge its value, and react as they see fit. If you read Catcher in the Rye and hate it, you know what? Awesome. I'm not going to argue with you, because you're the kind of person who reads books, and that means you're the kind of person capable of making your informed, personal choices. I like that in a person. Maybe we should hang out.

The big problem with parental responsibility, of course, is that it's hard. The king and queen in Sleeping Beauty would have had to spend 16 years teaching their daughter instead of hiding the truth and trusting some fairies to make it all work out. That's hard, and I know it; I have 4.9 children of my own, so I know exactly how hard it is. But they're my children, and I need to be willing to act like a grown-up and take responsibility for them. Someday soon I'm going to have to read a book I don't want to read, and/or a book I completely hate, because my daughter wants to read it, and I need to be involved in her education. I am not going to enjoy this process, and I may very well wish that someone would just take it out of the library altogether to save me the trouble. But someone else is going to love it, and maybe even learn from it, and I can't take that away from them. They deserve the same right I had to love it or hate it at their own discretion.

Let's increase the amount of wisdom and responsibility in the world. Celebrate Banned Books Week by going out and reading one.

September 21, 2011

Of all the gin joints, in all the towns, in all the world…

Secret Projects and Cool Events

Cool event first: I'm a huge gaming nerd, as you may be aware, and Magic: the Gathering is releasing a new, gothic horror-themed set this weekend. You may be able to guess where this is going. I talked to my friends at Epic Puzzles & Games in West Valley, UT, and not only will I be playing in their midnight Prerelease tournament, I'll be giving away some prizes. You see, the set includes a lot of demons, so players at the tournament will be able to earn cool stuff by killing them, kind of like unlocking achievements in a video game. Come to the tournament, open the shiny new cards, and play a few games; as soon as you kill a demon, shout it out and win a prize:

The John Cleaver Award: The first person to kill a demon wins a signed copy of I AM NOT A SERIAL KILLER.

The Mr. Monster Award: The first person to kill two demons wins a signed copy of MR. MONSTER.

The Serial Killer Award: The first person to kill three demons wins an I AM NOT A SERIAL KILLER T-shirt.

If you're a Magic player of any kind, hardcore or casual, Prerelease tournaments are a blast–they're very fun, very laid-back, and a great way to see the new cards. The new set, Innistrad, is full of imperious vampires and slavering werewolves and frightened peasants with pitchforks. Come by and hang out this Friday night at midnight. It's going to be awesome.

Now: on to the secret project. If you follow me on Twitter or Facebook you've probably seen some cryptic comments about fezzes and mustaches and trips to costume shops. What does it all mean? The answer, as with so many of the weird things I do, involves Brandon Sanderson.

Brandon has a large, unfinished room in his basement, initially intended as a movie room, but he has decided to finish it as a sitting room/game room/writing room, decorated in the style of an old explorer's club: old-timey globes, weathered maps, antique navigation equipment, artifacts from real and alternate histories, and portraits on the walls of the club's esteemed past members. The portraits, of course, will be pictures of us with big bushy mustaches and pith helmets, holding blunderbusses and standing in front of dinosaurs and doing other similarly explorer-ish things. It's going to be awesome.

So Brandon and Jordo (his brother, and the producer of Writing Excuses) and Peter (Brandon's assistant) and some other people in our circle of weirdos started growing out beards and preparing for the photos. I didn't want to do a big beard or mustache, though, because I tried that a year or so ago and really didn't like it. I was, however, growing out my hair, so I decided to go a different direction with my costume: long hair, a pencil mustache, a white suit, and a fez. My dad has a replica Walther P38, the sidearm a lot of officers used in World War 2, so I threw that in as well. The result was a cool sort of Moroccan hit man kind of look that worked perfectly. It all came together last night, and the photos turned out great.

The photo we chose for the actual portrait is currently being photoshopped into a variety of scenes: an archeological dig, a casbah, a street market, and so on, to see what we like best. I'll post it here when it's done. Shooting the photos was a lot of fun, and I can't wait to see what the other guys do for theirs.