Cameron McNeish's Blog, page 3

January 31, 2017

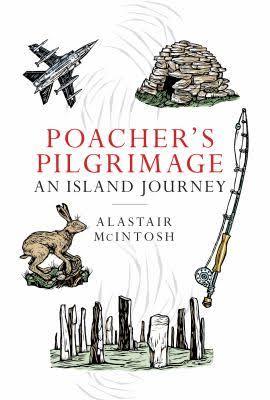

Poacher's Pilgrimage, by Alastair McIntosh (Birlinn) - Review

ABOUT 20 years ago I made a television programme with an American backpacker who had learned much of his ‘craft’ from native North American sources. I was intrigued by the notion of learning from those who had recognised something fundamental and vitally important in their relationship with the natural world, a connection we have lost in our modern world.But what of our Scottish native sources? The natural world was central to the beliefs of the ancient Celts, who tended to build their temples or cells sited in such a way as to exploit the energies of the earth. A shrine to Manannan, the lord of the waters, might be built near a river.Certain places held certain kinds of power, depending on factors such as the stone underlying them, the kinds of vegetation that grew and the positioning of nearby hills or waterways. Some places were for healing, some for energizing, some conducive to contemplation while others may simply have had an uncomfortable or uncanny atmosphere.Certainly, the ancient Celts knew few cities or towns, and their landscapes were generally those of forests, woods, mountains or seashores. The natural world was vitally important to them – spiritually so, for the sky and the unspoiled land provided a relationship between man and the cosmos, a relationship that is almost unknown to us today, a relationship – not unknown to other ancient belief systems – that our modern society has allowed to wither and atrophy.In his new book, Poacher’s Pilgrimage, author Alastair McIntosh examines a broad swathe of issues including spirituality, history, landscape and the Gaelic language, all in the context of a 12 day walk through the landscapes of his childhood, from Rodel in the south of Harris to the Butt of Lewis, an island that is littered with artefacts of the distant past – stone circles, beehive huts, holy wells and temples, a landscape that even today is suffused in a spirit of place.Using his knowledge of ecology, history and religion, McIntosh, a practicing Quaker, explores the meaning of these places and what they meant to our ancestors and, in turn, what they may mean to us today. On a very different level he uses the solitude and the beauty of the landscapes he passes through to examine what he describes as an ‘immram or ioramm’ – a kind of pilgrim voyage towards an ecology of the imagination.A fascinating aspect of this journey was in the recognition of nature as a divine mirror of the cycles and power of the universe and animals, lochs, trees, stones, the sun, moon, and seasons as reflections of a sovereign God, by a man who actively campaigns for peace, a man who spends considerable amounts of time lecturing to soldiers, to army officers, to military commanders the necessity for non-violence.And he’s convincing – how can you spend time in such places without wanting to know the meaning of it all, how can we correlate the grandeur and beauty of our world with the corruption of mankind that weighs so heavily on world peace?This is a book I’ve been waiting for years to read. I’ve learned so much from it and Alastair McIntosh has encouraged me to try and discover more, to make my own personal ‘immram.’But more than that McIntosh relates a joyful story, full of warmth, humour and passion, of how we can learn from the past to make our future brighter and safer and rediscover those things that our Celtic ancestors found to be absolutely essential for a balanced and thriving ecology of mind, spirit and land.

ABOUT 20 years ago I made a television programme with an American backpacker who had learned much of his ‘craft’ from native North American sources. I was intrigued by the notion of learning from those who had recognised something fundamental and vitally important in their relationship with the natural world, a connection we have lost in our modern world.But what of our Scottish native sources? The natural world was central to the beliefs of the ancient Celts, who tended to build their temples or cells sited in such a way as to exploit the energies of the earth. A shrine to Manannan, the lord of the waters, might be built near a river.Certain places held certain kinds of power, depending on factors such as the stone underlying them, the kinds of vegetation that grew and the positioning of nearby hills or waterways. Some places were for healing, some for energizing, some conducive to contemplation while others may simply have had an uncomfortable or uncanny atmosphere.Certainly, the ancient Celts knew few cities or towns, and their landscapes were generally those of forests, woods, mountains or seashores. The natural world was vitally important to them – spiritually so, for the sky and the unspoiled land provided a relationship between man and the cosmos, a relationship that is almost unknown to us today, a relationship – not unknown to other ancient belief systems – that our modern society has allowed to wither and atrophy.In his new book, Poacher’s Pilgrimage, author Alastair McIntosh examines a broad swathe of issues including spirituality, history, landscape and the Gaelic language, all in the context of a 12 day walk through the landscapes of his childhood, from Rodel in the south of Harris to the Butt of Lewis, an island that is littered with artefacts of the distant past – stone circles, beehive huts, holy wells and temples, a landscape that even today is suffused in a spirit of place.Using his knowledge of ecology, history and religion, McIntosh, a practicing Quaker, explores the meaning of these places and what they meant to our ancestors and, in turn, what they may mean to us today. On a very different level he uses the solitude and the beauty of the landscapes he passes through to examine what he describes as an ‘immram or ioramm’ – a kind of pilgrim voyage towards an ecology of the imagination.A fascinating aspect of this journey was in the recognition of nature as a divine mirror of the cycles and power of the universe and animals, lochs, trees, stones, the sun, moon, and seasons as reflections of a sovereign God, by a man who actively campaigns for peace, a man who spends considerable amounts of time lecturing to soldiers, to army officers, to military commanders the necessity for non-violence.And he’s convincing – how can you spend time in such places without wanting to know the meaning of it all, how can we correlate the grandeur and beauty of our world with the corruption of mankind that weighs so heavily on world peace?This is a book I’ve been waiting for years to read. I’ve learned so much from it and Alastair McIntosh has encouraged me to try and discover more, to make my own personal ‘immram.’But more than that McIntosh relates a joyful story, full of warmth, humour and passion, of how we can learn from the past to make our future brighter and safer and rediscover those things that our Celtic ancestors found to be absolutely essential for a balanced and thriving ecology of mind, spirit and land.

Published on January 31, 2017 12:04

Mixed success at Celtic Connections 2017

It was wonderful to escape the dark news that seems to continually emanate from our tellies and radios for a few days. The insane antics of Donald Trump and the ill thought out and desperate partnerships that Theresa May is trying to forge seemed a long way away and on a different planet.You're probably thinking I escaped to the mountains for a while but I didn't. I was in Glasgow for a week for the wonderful Celtic Connections festival.It's always difficult to select a few days together for CC - inevitably there are concerts that I'd love to attend that fall outside my allotted block of dates and this year we did fairly well. We managed six concerts and one afternoon talk, although I have to confess a couple of the concerts were a disappointment.But first the good ones, and they were really good. Indeed I was suggest that Duncan Chisholm's The Gathering bordered on genius. This is the kind of music that makes me proud to be Scots, tunes and slow airs that get under your skin and make you tremble in delight. During one particular piece the words of Norman MacCaig's A Man in Assynt were read and the combination of the music and the wonderfully eloquent words brought the tears running down my cheeks.The other brilliant show was brought by the Irish-American all female band, Cherish the Ladies. I'm a long-time fan of this band and I love their treatment of Irish music. This time they brought some superb Irish dancers to the stage, including a wonderfully confident 5-year old, and a beautiful trio of singers from Newfoundland. It was a superbly uplifting evening.Who would have thought that in the early days of Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny that the folk-rock band Fairport Convention would, one day, celebrate 50 years on the road. It was a joy to hear them, although Thompson and Denny are no longer with the band. (Sandy Denny sadly died at a ridiculously young age). The others were in good form, including another of the originals, Dave Pegg, and the old guys rocked the Fruitmarket like young things.I was looking forward to hearing Robyn Stapleton singing Burns but we were a bit late turning up for the concert at the St Andrews in the Square venue and had to sit through the concert on the hard wooden pews of the balcony. Up there, high above the stage and the audience, the acoustics were dreadful and what should have been a great concert turned out to be pretty poor, simply because we couldn't make out any words and the sounds were distorted. We won't make that mistake again.Two concerts disappointed us. Four Men and a Dog were talented enough but insisted on playing reel after reel at full speed with little respite. Their chosen songs weren't that impressive either. Going at full speed for most of the set can be exhausting, for the band as well as the audience and that was also the problem with Dirk Powell. I like this Appallachian singer and multi-instrumentalist but after a couple of songs he seemed to hand everything to an cajun accordianist who simply took over the show. I had come to hear Dirk Powell, not someone I'd never heard of, and this show was a major disappointment. I suspect many others were disappointed too because a lot of people left well before the end.We went along to one of the afternoon talks. Actor David Hayman was supposed to take about the healing effects of music on those living close to the age, in poverty, both at home and abroad, but David just plugged his charity Spirit Aid. I would point out that this charity is definitely well worth supporting but when someone in the audience asked "What about the music?" David shrugged and told us we'd been conned by the festival's organisers. Apparently he didn't know he had to talk about music until that day.Such festivals can often be a hit or miss affair and this is the first year in many that we were disappointed. However, the good concerts more than made up for it and Celtic Connections is the best music festival I know. I just hope it doesn't grow any bigger and I sincerely hope it won't be tempted to go down the route of bringing in "pop" music to swell the popularity. Keep it as a roots and traditional festival and it will continue to delight the thousands who faithfully attend each year.

Published on January 31, 2017 11:52

October 15, 2016

In Thrall to Ben Macdui

Ben Macdui from the westWE sat by the view indicator on the summit of Ben Macdhui, Britain’s second highest mountain, and found it hard to believe that here on the roof of Scotland on a fine summer day we had the place to ourselves.The sun shone warmly, even at a height of 4,300 feet, from a clear blue sky and it was so quiet and still that the sound of an insect flying past was a noisy intrusion. Swifts scythed through the still air and the occasional creaky croak of a ptarmigan reminded us that if global warming continues to manifest itself in such hot summers such cold-loving birds as the ptarmigan and the glorious snow bunting will vanish from these slopes forever.With its jet black mantle and dazzling white wings with ebony primaries the cock snow bunting is as vivid in these elemental surroundings as its song is intense. You’ll often see them by the summit of Ben Macdui, searching for crumbs of food left by picnicking hillwalkers.Of all the bird songs there can be few as moving and evocative as that of this little chaffinch-sized bird. A rare breeder in Scotland, the snow bunting is a bird of the high and lonely places, a black and white fleck of beauty amid the harsh wind-scoured tundra. His outpouring of song is a moving and powerful anthem to these wonderful Arctic surroundings and like the patches of purple moss campion that clings to life amid the stony gravel of these high places, the snow bunting is a reminder of the beauty that exists in an environment where life is harsh and uncompromising – there’s a sermon in there somewhere…

Ben Macdui from the westWE sat by the view indicator on the summit of Ben Macdhui, Britain’s second highest mountain, and found it hard to believe that here on the roof of Scotland on a fine summer day we had the place to ourselves.The sun shone warmly, even at a height of 4,300 feet, from a clear blue sky and it was so quiet and still that the sound of an insect flying past was a noisy intrusion. Swifts scythed through the still air and the occasional creaky croak of a ptarmigan reminded us that if global warming continues to manifest itself in such hot summers such cold-loving birds as the ptarmigan and the glorious snow bunting will vanish from these slopes forever.With its jet black mantle and dazzling white wings with ebony primaries the cock snow bunting is as vivid in these elemental surroundings as its song is intense. You’ll often see them by the summit of Ben Macdui, searching for crumbs of food left by picnicking hillwalkers.Of all the bird songs there can be few as moving and evocative as that of this little chaffinch-sized bird. A rare breeder in Scotland, the snow bunting is a bird of the high and lonely places, a black and white fleck of beauty amid the harsh wind-scoured tundra. His outpouring of song is a moving and powerful anthem to these wonderful Arctic surroundings and like the patches of purple moss campion that clings to life amid the stony gravel of these high places, the snow bunting is a reminder of the beauty that exists in an environment where life is harsh and uncompromising – there’s a sermon in there somewhere… The lovely moss campionI’ve lost count of how many times I’ve visited the summit of Ben Macdui but I never tire of it. Many moons ago, when as a young man I worked for an Aviemore-based company called Highland Guides, I brought folk up here twice a week, on a Tuesday and a Thursday. I’ve climbed this mountain more often than any other.I love the place. I love its spaciousness, I love its vast, open skies, I love how it drops abruptly into the deep chasm of the Lairig Ghru, I love its views that can be as widespread as Morven in Caithness to the Lammermuirs in Lothian, and I love the fact that you can wander on its flanks in any number of different ways; from Cairn Gorm, from Derry Lodge in the south via Carn a’Mhaim or by Derry Cairngorm, or up the steep inclines beside the March Burn from the Lairig Ghru.The standard route from the car park on Cairn Gorm has so many spectacular views the walk becomes a series of visual highpoints and despite the fact that other mountains in Scotland may be steeper, or more pointedly dramatic, there is nothing to compare with high-level wandering in the Cairngorms.

The lovely moss campionI’ve lost count of how many times I’ve visited the summit of Ben Macdui but I never tire of it. Many moons ago, when as a young man I worked for an Aviemore-based company called Highland Guides, I brought folk up here twice a week, on a Tuesday and a Thursday. I’ve climbed this mountain more often than any other.I love the place. I love its spaciousness, I love its vast, open skies, I love how it drops abruptly into the deep chasm of the Lairig Ghru, I love its views that can be as widespread as Morven in Caithness to the Lammermuirs in Lothian, and I love the fact that you can wander on its flanks in any number of different ways; from Cairn Gorm, from Derry Lodge in the south via Carn a’Mhaim or by Derry Cairngorm, or up the steep inclines beside the March Burn from the Lairig Ghru.The standard route from the car park on Cairn Gorm has so many spectacular views the walk becomes a series of visual highpoints and despite the fact that other mountains in Scotland may be steeper, or more pointedly dramatic, there is nothing to compare with high-level wandering in the Cairngorms. Walkers crossing the plateau close to Lohan BuidheWith the highest land mass in Britain over 3000 feet and 4000 feet you can walk for hours at these elevations with a wide, open sky above you and extraordinary views all around you. There simply isn’t anything to compare with it in these islands. But the effects of popularity are fast becoming apparentOn our walk from Coire Cas across the Cairngorm plateau by a drought-shrivelled Lochan Bhuidhe my companion, who hadn’t been on these slopes for some years, remarked on the increased erosion of the footpaths, the number of unnecessary waymarking cairns that line the route and the number of stone shelters that exist on Macdui’s summit slopes and on the ridge leading to the mountain’s northern top.Thirteen years ago the Government agency that preceded the National Park Authority, the Cairngorms Partnership, singularly failed to live up to its promises of removing all these man-made eyesores. The National Park Authority, apparently obsessed with housing developments and unsure of its role in nature and landscape conservation, has fared little better.It’s about time all these ad hoc shelters and waymarking cairns are removed - the slopes of this important mountain should be returned to their natural wild grandeur. When I chaired the Nevis Partnership we worked alongside the John Muir Trust and other stakeholders to clear all the eyeball searing detritis from the summit of Ben Nevis – surely our second highest summit deserves nothing less?Intoxicated by the hot sun and the rarefied air of the summit we made our way down the scree-strewn slopes to the top of Coire Sputain Dearg, searching for dwarf cudweed, the wee brother of the edelweiss. A spring, seeping from the sun-scorched ground, bubbled through a bed of golden lichens before maturing into a series of small, sky-blue pools, the shining levels that are magnified a thousand times in the lower levels of Loch Etchachan, its stony shores caressing the three-thousand foot contour.We wondered at the beauty of the place and in that wonder there was an instinctive recognition of the existence of order, a determined pattern behind the behaviour of things, a celebration of order and harmony. For those few hours we felt part of it. In a land where the basic elements of rock, air and water so heavily predominate it sometimes seems odd that there should be any illusion of welcome. Vast wind scoured slopes and gashes of glens offer little in the way of comfort or ease, and yet up here the untroubled waters and the ancient stones cast a spell as soothing as they are dramatic. The high lonely lochans reflect the mood of the skies, which in turn dictate the future, ordained by the winds and clouds of Biera the goddess of weather and storms.Such an experience is very special. These places have taught me the simplicity of ‘being’, uncluttered by everyday things and thoughts, the ascending grace conceded by these vast lands to all who are prepared to seek it. It’s a powerful lesson but you must also realise that while these hills are so powerful in their own way, they are also sensitive, fragile even. Our tenuous relationship needs to be nurtured. Along with a small sparrow-like bird, tiny deep-rooted plants and great granite mountains, we belong to a biotic community and it’s only when we view our relationship from that stance that we can begin to understand it and benefit from it.

Walkers crossing the plateau close to Lohan BuidheWith the highest land mass in Britain over 3000 feet and 4000 feet you can walk for hours at these elevations with a wide, open sky above you and extraordinary views all around you. There simply isn’t anything to compare with it in these islands. But the effects of popularity are fast becoming apparentOn our walk from Coire Cas across the Cairngorm plateau by a drought-shrivelled Lochan Bhuidhe my companion, who hadn’t been on these slopes for some years, remarked on the increased erosion of the footpaths, the number of unnecessary waymarking cairns that line the route and the number of stone shelters that exist on Macdui’s summit slopes and on the ridge leading to the mountain’s northern top.Thirteen years ago the Government agency that preceded the National Park Authority, the Cairngorms Partnership, singularly failed to live up to its promises of removing all these man-made eyesores. The National Park Authority, apparently obsessed with housing developments and unsure of its role in nature and landscape conservation, has fared little better.It’s about time all these ad hoc shelters and waymarking cairns are removed - the slopes of this important mountain should be returned to their natural wild grandeur. When I chaired the Nevis Partnership we worked alongside the John Muir Trust and other stakeholders to clear all the eyeball searing detritis from the summit of Ben Nevis – surely our second highest summit deserves nothing less?Intoxicated by the hot sun and the rarefied air of the summit we made our way down the scree-strewn slopes to the top of Coire Sputain Dearg, searching for dwarf cudweed, the wee brother of the edelweiss. A spring, seeping from the sun-scorched ground, bubbled through a bed of golden lichens before maturing into a series of small, sky-blue pools, the shining levels that are magnified a thousand times in the lower levels of Loch Etchachan, its stony shores caressing the three-thousand foot contour.We wondered at the beauty of the place and in that wonder there was an instinctive recognition of the existence of order, a determined pattern behind the behaviour of things, a celebration of order and harmony. For those few hours we felt part of it. In a land where the basic elements of rock, air and water so heavily predominate it sometimes seems odd that there should be any illusion of welcome. Vast wind scoured slopes and gashes of glens offer little in the way of comfort or ease, and yet up here the untroubled waters and the ancient stones cast a spell as soothing as they are dramatic. The high lonely lochans reflect the mood of the skies, which in turn dictate the future, ordained by the winds and clouds of Biera the goddess of weather and storms.Such an experience is very special. These places have taught me the simplicity of ‘being’, uncluttered by everyday things and thoughts, the ascending grace conceded by these vast lands to all who are prepared to seek it. It’s a powerful lesson but you must also realise that while these hills are so powerful in their own way, they are also sensitive, fragile even. Our tenuous relationship needs to be nurtured. Along with a small sparrow-like bird, tiny deep-rooted plants and great granite mountains, we belong to a biotic community and it’s only when we view our relationship from that stance that we can begin to understand it and benefit from it. Loch AvonThe Cairngorms’ lochs, the shining levels, provide another source of wonder. Further on, deep in its own craggy sand-fringed cradle, lay Loch Avon, the unchallenged jewel of the Cairngorms. The path that drops down into Loch Avon’s basin is badly worn and dangerously eroded but fails to diminish the Gothic splendour of the place. The sheer walls of the Sticil, the square-cut granite edifice that dominates the head of Loch Avon above its skirts of tumbled rock, casts its dark shadow wide but not wide enough to subdue the joyous songs of the waterfalls that crash down the white slabs from the plateau beyond it. The green meadow, the meandering stream, the white-sands that fringe the translucent jade of the loch all contrast vividly with the steep rock walls above. This is a place closed-in and jealously guarded by the mountains and of all the landscapes I know this is the one I cherish most. And it’s here that you’ll find the Shelter Stone, Scotland’s best known howff.Prime Minister Gladstone reputedly sheltered below it's solid bulk and it's said that the Prince of Wales was fond of bivvying there on school trips from Gordonstoun. Other residents were less salubrious - generations of vagabonds and itinerant rogues on the run from the law of the day, and of course modern climbers and hill walkers.Crouching over a jumble of boulder scree below the precipitous flanks of the Sticil, the Shelter Stone is an enormous rock which forms a substantial roof over a natural horizontal cleavage, a cave which is reputed to have once held "eighteen armed men".The men of yesteryear must have been very small, or perhaps the Shelter Stone has moved and reduced the space below it, but I can't imagine more than half a dozen average sized individuals sheltering in there nowadays, but the fact is that many still do, and indeed enjoy the experience, despite the ghostly legends of many years.In 1924 a Visitor's Book was left in the cavern and many volumes are kept in the Cairngorm Club's library in Aberdeen. Some of the entries make fascinating reading. One party claims to have experienced a rather strange encounter with the legendary water horse of Loch Avon. Hearing a strange stamping and whinneying during the night they went outside the investigate and saw, "a great white horse with flashing eyes and a dripping mane. No other than the supernatural Water Horse or Each Uisghe from the unplumbed depths of Loch Avon...."In her fine book, Speyside to Deeside, published in 1956, Brenda G Macrow wrote: "For my own part, I have met a young man who, while spending a night under the Shelter Stone alone, heard a climber approach at about midnight, pause at the entrance, and then go away again. He called, but there was no answer. Emerging quickly from the cave, he could see no sign of anyone (although it was brilliant moonlight) and no footprints in the snow."An old friend of mine, the late Syd Scroggie from Strathmartine, claims to have once sat outside the howff and watched a giant figure walk towards the loch and simply vanish into thin air. Syd believes he saw the image of Fearlas Mor, the Great Grey Man of Ben MacDhui. But could it have been the dreaded Fahm, a grisly monster which was once believed to haunt the summits around Loch Avon? James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, in his poem Glen-Avin from The Queen's Wake tells the fearsome story."...Yet still at eve, or midnight drear,When wintry winds begin to sweep,When passing shrieks assail thine ear,Or murmours by the mountain steep;When from the dark and sedgy dells,Come eldritch cries of wildered men;Or wind-harp at thy window swells -Beware the sprite of Avin Glen!"The climb out of the Loch Avon basin, on another steep and eroded path, leads to the grassy extravagances of Coire Dhomhain and the edge of the plateau before it drops into Coire an t-Sneachda, the snowy corrie with its pools and rock rubble and echoes of climbs in both summer and winter. The memories of those climbing years always embrace me as I descend the Goat Track, a footpath that has become so badly worn that it is now potentially dangerous. But despite the underfoot problems I realise again just how much I love these places and how badly I want to see them protected from man’s extravagances.As we left the bowl of Coire an t-Sneachda my whispered prayers, thrown at random to the mountain gods, was that the Cairngorms National Park will overcome man’s contrivances. Like many others I need these places like life-blood but the creation of National Parks comes with huge responsibilities. If success is measured in the number of visitors to an area then we must be prepared to repair the unintentional damage caused by those visitors. The Cairngorms will not be worthy of the title of National Park if we can’t protect these precious places from continual degradation. I would urge the National Park Authority members – the councillors, the economists, the local entrepeneurs and the community developers - to memorise the words of the late WH Murray, Scotland’s finest ever mountain writer and conservationist, who said: “the human privilege is to take decisions for more than our own good; our reward, that it turns out to be best for us too.”

Loch AvonThe Cairngorms’ lochs, the shining levels, provide another source of wonder. Further on, deep in its own craggy sand-fringed cradle, lay Loch Avon, the unchallenged jewel of the Cairngorms. The path that drops down into Loch Avon’s basin is badly worn and dangerously eroded but fails to diminish the Gothic splendour of the place. The sheer walls of the Sticil, the square-cut granite edifice that dominates the head of Loch Avon above its skirts of tumbled rock, casts its dark shadow wide but not wide enough to subdue the joyous songs of the waterfalls that crash down the white slabs from the plateau beyond it. The green meadow, the meandering stream, the white-sands that fringe the translucent jade of the loch all contrast vividly with the steep rock walls above. This is a place closed-in and jealously guarded by the mountains and of all the landscapes I know this is the one I cherish most. And it’s here that you’ll find the Shelter Stone, Scotland’s best known howff.Prime Minister Gladstone reputedly sheltered below it's solid bulk and it's said that the Prince of Wales was fond of bivvying there on school trips from Gordonstoun. Other residents were less salubrious - generations of vagabonds and itinerant rogues on the run from the law of the day, and of course modern climbers and hill walkers.Crouching over a jumble of boulder scree below the precipitous flanks of the Sticil, the Shelter Stone is an enormous rock which forms a substantial roof over a natural horizontal cleavage, a cave which is reputed to have once held "eighteen armed men".The men of yesteryear must have been very small, or perhaps the Shelter Stone has moved and reduced the space below it, but I can't imagine more than half a dozen average sized individuals sheltering in there nowadays, but the fact is that many still do, and indeed enjoy the experience, despite the ghostly legends of many years.In 1924 a Visitor's Book was left in the cavern and many volumes are kept in the Cairngorm Club's library in Aberdeen. Some of the entries make fascinating reading. One party claims to have experienced a rather strange encounter with the legendary water horse of Loch Avon. Hearing a strange stamping and whinneying during the night they went outside the investigate and saw, "a great white horse with flashing eyes and a dripping mane. No other than the supernatural Water Horse or Each Uisghe from the unplumbed depths of Loch Avon...."In her fine book, Speyside to Deeside, published in 1956, Brenda G Macrow wrote: "For my own part, I have met a young man who, while spending a night under the Shelter Stone alone, heard a climber approach at about midnight, pause at the entrance, and then go away again. He called, but there was no answer. Emerging quickly from the cave, he could see no sign of anyone (although it was brilliant moonlight) and no footprints in the snow."An old friend of mine, the late Syd Scroggie from Strathmartine, claims to have once sat outside the howff and watched a giant figure walk towards the loch and simply vanish into thin air. Syd believes he saw the image of Fearlas Mor, the Great Grey Man of Ben MacDhui. But could it have been the dreaded Fahm, a grisly monster which was once believed to haunt the summits around Loch Avon? James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, in his poem Glen-Avin from The Queen's Wake tells the fearsome story."...Yet still at eve, or midnight drear,When wintry winds begin to sweep,When passing shrieks assail thine ear,Or murmours by the mountain steep;When from the dark and sedgy dells,Come eldritch cries of wildered men;Or wind-harp at thy window swells -Beware the sprite of Avin Glen!"The climb out of the Loch Avon basin, on another steep and eroded path, leads to the grassy extravagances of Coire Dhomhain and the edge of the plateau before it drops into Coire an t-Sneachda, the snowy corrie with its pools and rock rubble and echoes of climbs in both summer and winter. The memories of those climbing years always embrace me as I descend the Goat Track, a footpath that has become so badly worn that it is now potentially dangerous. But despite the underfoot problems I realise again just how much I love these places and how badly I want to see them protected from man’s extravagances.As we left the bowl of Coire an t-Sneachda my whispered prayers, thrown at random to the mountain gods, was that the Cairngorms National Park will overcome man’s contrivances. Like many others I need these places like life-blood but the creation of National Parks comes with huge responsibilities. If success is measured in the number of visitors to an area then we must be prepared to repair the unintentional damage caused by those visitors. The Cairngorms will not be worthy of the title of National Park if we can’t protect these precious places from continual degradation. I would urge the National Park Authority members – the councillors, the economists, the local entrepeneurs and the community developers - to memorise the words of the late WH Murray, Scotland’s finest ever mountain writer and conservationist, who said: “the human privilege is to take decisions for more than our own good; our reward, that it turns out to be best for us too.”

Published on October 15, 2016 09:16

August 21, 2016

Schiehallion, the Mystical Mountain

Schiehallion from Loch RannochIT was a dour day for the high tops but it wasn’t windy and it wasn’t wet. The stillness and silence of the day was exacerbated by the low clouds that shrouded the hill, mists that could well have been the frozen breath of the Cailleach Bheur, the blue hag who according to Rannoch legend rides the wings of the storms to deal out her icy death to the unfortunate traveller.The mist didn’t perturb me too much. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve climbed Perthshire’s Schiehallion and I knew there was a good footpath, built some years ago by the John Muir Trust, which would carry me up to the hill’s long eastern ridge. Once I reached the ridge it was a simple case of following a compass bearing more or less due west to the rocky summit.That navigational confidence was important today though, because I was actually ‘guiding’ a guest up the mountain, a man I had known for some years by repute, a man whose interest in Schiehallion went way beyond peak-bagging.Although its name has the cut and thrust of a battle-cry and its conical shape was once used to help calculate the weight of the Earth, Schiehallion, 1083m/3553ft, translates into something much less macho - Sidh Chailleann, the Fairy Hill of the Caledonians. Others scholars have suggested the name might mean 'the maiden's pap', or 'constant storm' and that latter interpretation certainly fits with the legend of the Cailleach Bheur.According to AD Cunningham’s excellent book Tales of Rannoch this old witch was once a familiar sight on Schiehallion: “Her face was blue with cold, her hair white with frost and the plaid that wrapped her bony shoulders was grey as the winter fields.”The old hag’s presence was clearly evident as my companion and I climbed onto the mountain’s long whaleback ridge. The air was still, visibility was down to a few metres and ice crystals decorated every boulder. There was little temptation to linger in the Cailleach Bheur’s cold grasp. You don’t have to believe in faeries to experience the chilling fingers of winter reach out to you…I’ve had the pleasure of climbing hills in Scotland with all kinds of people – famous mountaineers, television celebrities, pop singers, musicians, artists – but few have been as intriguing as my guest on Schiehallion. But before I introduce him to you let me set the scene, particularly for those of you who may be unfamiliar with the more mystical aspects of this Perthshire mountain.

Schiehallion from Loch RannochIT was a dour day for the high tops but it wasn’t windy and it wasn’t wet. The stillness and silence of the day was exacerbated by the low clouds that shrouded the hill, mists that could well have been the frozen breath of the Cailleach Bheur, the blue hag who according to Rannoch legend rides the wings of the storms to deal out her icy death to the unfortunate traveller.The mist didn’t perturb me too much. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve climbed Perthshire’s Schiehallion and I knew there was a good footpath, built some years ago by the John Muir Trust, which would carry me up to the hill’s long eastern ridge. Once I reached the ridge it was a simple case of following a compass bearing more or less due west to the rocky summit.That navigational confidence was important today though, because I was actually ‘guiding’ a guest up the mountain, a man I had known for some years by repute, a man whose interest in Schiehallion went way beyond peak-bagging.Although its name has the cut and thrust of a battle-cry and its conical shape was once used to help calculate the weight of the Earth, Schiehallion, 1083m/3553ft, translates into something much less macho - Sidh Chailleann, the Fairy Hill of the Caledonians. Others scholars have suggested the name might mean 'the maiden's pap', or 'constant storm' and that latter interpretation certainly fits with the legend of the Cailleach Bheur.According to AD Cunningham’s excellent book Tales of Rannoch this old witch was once a familiar sight on Schiehallion: “Her face was blue with cold, her hair white with frost and the plaid that wrapped her bony shoulders was grey as the winter fields.”The old hag’s presence was clearly evident as my companion and I climbed onto the mountain’s long whaleback ridge. The air was still, visibility was down to a few metres and ice crystals decorated every boulder. There was little temptation to linger in the Cailleach Bheur’s cold grasp. You don’t have to believe in faeries to experience the chilling fingers of winter reach out to you…I’ve had the pleasure of climbing hills in Scotland with all kinds of people – famous mountaineers, television celebrities, pop singers, musicians, artists – but few have been as intriguing as my guest on Schiehallion. But before I introduce him to you let me set the scene, particularly for those of you who may be unfamiliar with the more mystical aspects of this Perthshire mountain. Clambering on the summit rocksI’ve already mentioned that Schiehallion was used in experiments to try and ascertain the density of the Earth. In 1774 the Astronomer Royal Neville Maskelyne chose Schiehallion for his measurements because of the hill’s relatively isolated position and conical shape. The experiment was based on the way the mountain’s own mass caused a pendulum to pull away from the vertical. The deflection of the pendulum provided Maskelyne with the information to allow him to calculate the mean density of the Earth, from which its mass and a value for Newton’s Gravitational constant could be worked out.I’m afraid I have no idea what that actually means, but I do know this. One of the assistants on the project, Charles Hutton, worked out a graphical system that measured areas of equal height. The system later became known as contour lines, and all of us who go to the hills have reason to be grateful for that particular discovery.But it was discovery of a more mystical nature I hoped for today. In his book AD Cunningham leaves a tantalising message: “The adventurer who lingers in the secret places of the mountains senses that the cailleach and the spirit life are still there, and he is aware that enchantment has not vanished from the world.”Enchantment has certainly not vanished from Schiehallion. Climb her slopes on a sunny summer’s evening and you will most certainly be enchanted by views across the rolling hills of Highland Perthshire to where Loch Rannoch stretches out towards the pocked mattress of the Rannoch Moor. Descend the hill at nightfall and hear the curious summer sounds of drumming snipe and roding woodcock or listen to the roars of rutting stags during the chilled days of late autumn. But Schiehallion has an allure that is not always comfortable. Shrouded in the snows of winter her cold charm is compelling, as she tempts you like a harlot, or a blue hag…The mountain and its immediate area are rich in superstition and legend and it’s at Uamh Tom a’Mhor-fhir, a cave in the upper reaches of Gleann Mor on the south side of the mountain, that Schiehallion’s faeries are supposed to dwell. I’ve never come across much evidence of faeries in the glen but years ago I did climb the hill with old friend Hamish Brown who pointed out to me a rock with ancient cup-and-saucer ring markings, evidence of old hut circles and the remains of shielings, reminders of an earlier way of life when glens like this were used for grazing cattle.Another old pal of the hills, the late Irvine Butterfield, once scolded me for making fun of the faery stories. “There are things on Schiehallion that shouldn’t be mocked,” he warned. And he was serious…In his book, A Highland Parish, published in 1928, Alexander Stewart suggests the Uamh Tom a’Mhor-fhir cave is in fact part of a huge cave system: “It has a fairly wide opening which extends for three or four yards. It then contracts and slants into total darkness in the bowels of the earth. Some miles to the east of this there is another opening, which tradition holds to be the other end of the cave. According to the traditional accounts, this cave was regarded as an abode of fairies and other supernatural beings, rather than a hiding place of mortals. The only men who were supposed to have lived there were individuals who were believed to have been in league with supernatural powers.”There are no cattle today and very little evidence of faery folk but you might well see, and indeed smell, Schiehallion’s feral goats, although I must confess I haven’t seen any goats here for years. But if you do spot some wild goats look out for the Ghobhar Bacach, the lame goat, who according to legend still limps about Schiehallion, always in milk, with a yield enough to supply the Fingalians, the fair-haired warrior giants under the command of Fionn MacCumhail, when they return from Ireland to take Scotland once again.There was little evidence of the Ghobhar Bacach as we crunched across the snows of the hill’s eastern ridge but the cold mists that clung to us suggested the Cailleach Bheur was keen to make her presence felt. Her attention was made even more credible because my companion was infinitely more in tune with these curios than I was.Lawrence Main was in the second week of a length-of-Britain pilgrimage visiting ancient, sacred sites. He had started his mammoth walk at the Callanish Standing Stones on Lewis and had worked his way south via Culloden’s Clava Cairns and Aberdeenshire’s Bennachie. I had collected him from his lonely camp at the head of Glen Lyon where he had been visiting the old yew tree at Fortingall (Pontius Pilate is said to have born in the area) and the Praying Hands of Mary, a curious set of split standing stones in the upper reaches of the glen.

Clambering on the summit rocksI’ve already mentioned that Schiehallion was used in experiments to try and ascertain the density of the Earth. In 1774 the Astronomer Royal Neville Maskelyne chose Schiehallion for his measurements because of the hill’s relatively isolated position and conical shape. The experiment was based on the way the mountain’s own mass caused a pendulum to pull away from the vertical. The deflection of the pendulum provided Maskelyne with the information to allow him to calculate the mean density of the Earth, from which its mass and a value for Newton’s Gravitational constant could be worked out.I’m afraid I have no idea what that actually means, but I do know this. One of the assistants on the project, Charles Hutton, worked out a graphical system that measured areas of equal height. The system later became known as contour lines, and all of us who go to the hills have reason to be grateful for that particular discovery.But it was discovery of a more mystical nature I hoped for today. In his book AD Cunningham leaves a tantalising message: “The adventurer who lingers in the secret places of the mountains senses that the cailleach and the spirit life are still there, and he is aware that enchantment has not vanished from the world.”Enchantment has certainly not vanished from Schiehallion. Climb her slopes on a sunny summer’s evening and you will most certainly be enchanted by views across the rolling hills of Highland Perthshire to where Loch Rannoch stretches out towards the pocked mattress of the Rannoch Moor. Descend the hill at nightfall and hear the curious summer sounds of drumming snipe and roding woodcock or listen to the roars of rutting stags during the chilled days of late autumn. But Schiehallion has an allure that is not always comfortable. Shrouded in the snows of winter her cold charm is compelling, as she tempts you like a harlot, or a blue hag…The mountain and its immediate area are rich in superstition and legend and it’s at Uamh Tom a’Mhor-fhir, a cave in the upper reaches of Gleann Mor on the south side of the mountain, that Schiehallion’s faeries are supposed to dwell. I’ve never come across much evidence of faeries in the glen but years ago I did climb the hill with old friend Hamish Brown who pointed out to me a rock with ancient cup-and-saucer ring markings, evidence of old hut circles and the remains of shielings, reminders of an earlier way of life when glens like this were used for grazing cattle.Another old pal of the hills, the late Irvine Butterfield, once scolded me for making fun of the faery stories. “There are things on Schiehallion that shouldn’t be mocked,” he warned. And he was serious…In his book, A Highland Parish, published in 1928, Alexander Stewart suggests the Uamh Tom a’Mhor-fhir cave is in fact part of a huge cave system: “It has a fairly wide opening which extends for three or four yards. It then contracts and slants into total darkness in the bowels of the earth. Some miles to the east of this there is another opening, which tradition holds to be the other end of the cave. According to the traditional accounts, this cave was regarded as an abode of fairies and other supernatural beings, rather than a hiding place of mortals. The only men who were supposed to have lived there were individuals who were believed to have been in league with supernatural powers.”There are no cattle today and very little evidence of faery folk but you might well see, and indeed smell, Schiehallion’s feral goats, although I must confess I haven’t seen any goats here for years. But if you do spot some wild goats look out for the Ghobhar Bacach, the lame goat, who according to legend still limps about Schiehallion, always in milk, with a yield enough to supply the Fingalians, the fair-haired warrior giants under the command of Fionn MacCumhail, when they return from Ireland to take Scotland once again.There was little evidence of the Ghobhar Bacach as we crunched across the snows of the hill’s eastern ridge but the cold mists that clung to us suggested the Cailleach Bheur was keen to make her presence felt. Her attention was made even more credible because my companion was infinitely more in tune with these curios than I was.Lawrence Main was in the second week of a length-of-Britain pilgrimage visiting ancient, sacred sites. He had started his mammoth walk at the Callanish Standing Stones on Lewis and had worked his way south via Culloden’s Clava Cairns and Aberdeenshire’s Bennachie. I had collected him from his lonely camp at the head of Glen Lyon where he had been visiting the old yew tree at Fortingall (Pontius Pilate is said to have born in the area) and the Praying Hands of Mary, a curious set of split standing stones in the upper reaches of the glen. A bronzed and bearded Lawrence MainLawrence writes walking guides for a living, and lectures on Earth Mysteries. He is a druid and the purpose of his long walk was to raise publicity for the Vegan Society. “If we were all vegans we would only need 10 million acres of agricultural land to supply our needs,“ he told me, “That’s a quarter of all the agricultural land in England and Wales alone.”I must confess my ham sandwiches tasted no less fine and I sipped hot coffee from my flask while Lawrence nibbled organic chocolate and drank water. He had asked me to accompany him on Schiehallion and while I was happy to do that it was obvious Lawrence’s interests were in the hill’s legends rather than her status as a Munro.As we crossed the exposed summit ridge, I became a little concerned about Lawrence for he had insisted on wearing shorts. The middle of March may be mild in his home territory of mid-Wales but here in Highland Perthshire at three thousand feet the weather was bitter and Lawrence’s non-leather vegan boots didn’t appear to be coping with the iced-up rocks. However, he struggled on manfully, and managed to gasp out the reasons why he had been so keen to climb Schiehallion.“This is one of the world’s Holy hills,” he told me between deep gulps of frigid air. “Druids believe there are three primary Holy Mountains - Mount Moriah in Palestine, Mount Sinai in Egypt, and Mount Heredom, although there is no hard evidence to show where that is.“Schiehallion has always been known as a mystical mountain by Gaelic-speaking highlanders – a source of inspiration and revelation to prophets and saints. Other hills in the UK with similar associations are Uisneach, situated at the geographical centre of Celtic Ireland, and Plinlimmon, close to the centre of Celtic Wales. Here Schiehallion lies at the centre of Celtic Scotland. Could that be mere coincidence?”“And what’s more there are those who believe Schiehallion was visited by Jesus Christ himself. In between his presentation to the Temple as a child and taking up his ministry at the age of 30, Jesus travelled extensively in the company of Joseph of Arimathea, a tin trader and merchant.“What we now know as Britain was once the tin-manufacturing centre of the world, so it’s not unreasonable to believe that Joseph came here. It’s entirely possible the young Jesus came with him. It’s also ironic that Christ’s judge, Pontius Pilate was allegedly born just over the hill in Fortingall, the son of a Roman officer.”

A bronzed and bearded Lawrence MainLawrence writes walking guides for a living, and lectures on Earth Mysteries. He is a druid and the purpose of his long walk was to raise publicity for the Vegan Society. “If we were all vegans we would only need 10 million acres of agricultural land to supply our needs,“ he told me, “That’s a quarter of all the agricultural land in England and Wales alone.”I must confess my ham sandwiches tasted no less fine and I sipped hot coffee from my flask while Lawrence nibbled organic chocolate and drank water. He had asked me to accompany him on Schiehallion and while I was happy to do that it was obvious Lawrence’s interests were in the hill’s legends rather than her status as a Munro.As we crossed the exposed summit ridge, I became a little concerned about Lawrence for he had insisted on wearing shorts. The middle of March may be mild in his home territory of mid-Wales but here in Highland Perthshire at three thousand feet the weather was bitter and Lawrence’s non-leather vegan boots didn’t appear to be coping with the iced-up rocks. However, he struggled on manfully, and managed to gasp out the reasons why he had been so keen to climb Schiehallion.“This is one of the world’s Holy hills,” he told me between deep gulps of frigid air. “Druids believe there are three primary Holy Mountains - Mount Moriah in Palestine, Mount Sinai in Egypt, and Mount Heredom, although there is no hard evidence to show where that is.“Schiehallion has always been known as a mystical mountain by Gaelic-speaking highlanders – a source of inspiration and revelation to prophets and saints. Other hills in the UK with similar associations are Uisneach, situated at the geographical centre of Celtic Ireland, and Plinlimmon, close to the centre of Celtic Wales. Here Schiehallion lies at the centre of Celtic Scotland. Could that be mere coincidence?”“And what’s more there are those who believe Schiehallion was visited by Jesus Christ himself. In between his presentation to the Temple as a child and taking up his ministry at the age of 30, Jesus travelled extensively in the company of Joseph of Arimathea, a tin trader and merchant.“What we now know as Britain was once the tin-manufacturing centre of the world, so it’s not unreasonable to believe that Joseph came here. It’s entirely possible the young Jesus came with him. It’s also ironic that Christ’s judge, Pontius Pilate was allegedly born just over the hill in Fortingall, the son of a Roman officer.” A frozen Lawrence on Schiehallion's summitI listened to Lawrence with a degree of scepticism but it’s also been suggested that after the disastrous Battle of Methven Robert the Bruce took refuge in a small castle on the north slopes of Schiehallion where he established the masonic ‘Sublime and Royal Chapter of Heredom,’ a chapter of the freemasons that had originally been constituted on the Holy top of Mount Moriah in the Kingdom of Judea. But why did the Bruce choose Schiehallion? Apparently because like Mount Moriah Schiehallion was thought to be a Holy Mountain, the “Mount Zion in the far north” as recorded in Psalm 48 in the Hebrew Old Testament. In his book, The Holy Land of Scotland, author Barry Dunford quotes the eighteenth century writings of the Chevalier de Berage on the origins of Freemasonry: “Their Metropolitan Lodge is situated on the Mountain of Heredom where the first Lodge was held in Europe and which exists in all its splendour. The General Council is still held there and it is the seal of the Sovereign Grand Master in office. This mountain is situated between the West and North of Scotland at sixty miles from Edinburgh.”Could Schiehallion be the Mount Heredom of the ancient scriptures?Lawrence and I originally planned to descend the rocky flanks to the west of the summit, a route that would take us to the head of Gleann Mor and the Tom a’Mhor-fhir cave but he looked half frozen. His long beard was tangled in ice and his knees were blue. He had grazed his leg on a sharp rock and blood poured from the injury. He would have to forsake the delights of Gleann Mor, the cup-and-saucer ring markings, the old shielings and the fairy cave at Uamh Tom a’Mhor-fhir for a direct descent back to the warmth of the car. We parted on the promise that he would return and enjoy the spiritual aspects of Schiehallion when the Cailleach Bheur had departed for the summer. I went off to reconsider my initial scepticism and recall the words of an old Perthshire cleric:“I love to view Schiehallion all aglow,

In blaze of beauty 'gainst the eastern sky,

Like a huge pyramid exalted high

O'er woodland fringing round its base below;

....

The Bible tells of Hebrew mountains grand,

Where such great deeds were done in days of old,

As render them more precious far than gold

in our conception of the Holy Land;

But every soul that seeks the heavenly road

May in Schiehallion, too, behold a Mount of God.From Schiehallion by Rev. John Sinclair

A frozen Lawrence on Schiehallion's summitI listened to Lawrence with a degree of scepticism but it’s also been suggested that after the disastrous Battle of Methven Robert the Bruce took refuge in a small castle on the north slopes of Schiehallion where he established the masonic ‘Sublime and Royal Chapter of Heredom,’ a chapter of the freemasons that had originally been constituted on the Holy top of Mount Moriah in the Kingdom of Judea. But why did the Bruce choose Schiehallion? Apparently because like Mount Moriah Schiehallion was thought to be a Holy Mountain, the “Mount Zion in the far north” as recorded in Psalm 48 in the Hebrew Old Testament. In his book, The Holy Land of Scotland, author Barry Dunford quotes the eighteenth century writings of the Chevalier de Berage on the origins of Freemasonry: “Their Metropolitan Lodge is situated on the Mountain of Heredom where the first Lodge was held in Europe and which exists in all its splendour. The General Council is still held there and it is the seal of the Sovereign Grand Master in office. This mountain is situated between the West and North of Scotland at sixty miles from Edinburgh.”Could Schiehallion be the Mount Heredom of the ancient scriptures?Lawrence and I originally planned to descend the rocky flanks to the west of the summit, a route that would take us to the head of Gleann Mor and the Tom a’Mhor-fhir cave but he looked half frozen. His long beard was tangled in ice and his knees were blue. He had grazed his leg on a sharp rock and blood poured from the injury. He would have to forsake the delights of Gleann Mor, the cup-and-saucer ring markings, the old shielings and the fairy cave at Uamh Tom a’Mhor-fhir for a direct descent back to the warmth of the car. We parted on the promise that he would return and enjoy the spiritual aspects of Schiehallion when the Cailleach Bheur had departed for the summer. I went off to reconsider my initial scepticism and recall the words of an old Perthshire cleric:“I love to view Schiehallion all aglow,

In blaze of beauty 'gainst the eastern sky,

Like a huge pyramid exalted high

O'er woodland fringing round its base below;

....

The Bible tells of Hebrew mountains grand,

Where such great deeds were done in days of old,

As render them more precious far than gold

in our conception of the Holy Land;

But every soul that seeks the heavenly road

May in Schiehallion, too, behold a Mount of God.From Schiehallion by Rev. John Sinclair

Published on August 21, 2016 05:32

July 20, 2016

Visiting A'Mhaighdean

The summit view from A'MhaighdeanDESPITE all the brouhaha of the recent Land Reform debate it was interesting that the legislators decided to leave the access provisions of the 2003 Act exactly as they were.Despite constant challenges from a handful of recalcitrant landowners those original access provisions have been extremely successful, legal rights that the Scottish public can be proud of as being amongst the finest and most progressive access legislation in the world.And while writers like Tom Weir and in particular Rennie MacOwan campaigned for a very long time to see Scotland’s de facto access rights become formalised much of the foundation of the Land Reform provisions was laid down during discussions at Letterewe House on the shores of Loch Maree in Wester Ross. The nearby Munro of A’Mhaighdean was central to those early discussions.The vast deer forests of Strathnashealag, Fisherfield and Letterewe have long been known as the Great Wilderness. The hills unashamedly expose the bare bones of the earth, folded into complex patterns and a series of long sinuous lochs betray the evidence of geological faults, subsequently carved out by the grinding of massive glaciers. These scoured-out basins form the grain of the land but excellent tracks weave their way through glens and up over the bealachs at their heads giving good access to the summits, and what summits they are! The heart of this Great Wilderness is dominated by the Torridonian sandstone peak of Ruadh Stac Mor and the grey quartzite peak of A' Mhaighdean, arguably the remotest of all Scotland's Munros. And if these are the remotest Munros then neighbouring Beinn a’ Chaisgein Mor, 2808ft/856m, could well be amongst the most remote of the Corbetts.The Letterewe access debate began when a hillwalker cycled into the estate and left his bike at Carnmore when he went off to climb A’Mhaighdean, 967m/3173ft. On his return he discovered his bicycle tyres had been let down by an estate employee. The erstwhile owner of the estate, multimillionaire Paul van Vlissingen, had stated he didn’t welcome walkers and a number of notices around the estate made this very clear.There was some consternation amongst outdoor organisations but it was a hill-going member of the aristocracy who actually took the initiative. John Mackenzie has a series of titles including Earl of Cromartie and Clan Chief of the Mackenzies, but amongst climbers he was known as the author of the Scottish Mountaineering Clubs guide Rock & Ice climbs in Skye. He was incensed that access to the Letterewe estate with its famous crags like Carnmore might be in jeopardy and said so publicly. A story appeared in one newspaper stating that John intended leading a clan march onto van Vlissingen’s land in protest!That march never happened but what did follow were two years of detailed debate involving not just Mackenzie and van Vlissingen, but also representatives of numerous bodies including the Ramblers and the Mountaineering Council of Scotland. These discussions eventually produced The Letterewe Accord, which guaranteed walkers certain rights, and for the very first time anywhere in Britain a landowner had acknowledged that recreational users had rights to roam over his land. This Accord document was very important in the following discussions that eventually produced the current access provisions of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act.

The summit view from A'MhaighdeanDESPITE all the brouhaha of the recent Land Reform debate it was interesting that the legislators decided to leave the access provisions of the 2003 Act exactly as they were.Despite constant challenges from a handful of recalcitrant landowners those original access provisions have been extremely successful, legal rights that the Scottish public can be proud of as being amongst the finest and most progressive access legislation in the world.And while writers like Tom Weir and in particular Rennie MacOwan campaigned for a very long time to see Scotland’s de facto access rights become formalised much of the foundation of the Land Reform provisions was laid down during discussions at Letterewe House on the shores of Loch Maree in Wester Ross. The nearby Munro of A’Mhaighdean was central to those early discussions.The vast deer forests of Strathnashealag, Fisherfield and Letterewe have long been known as the Great Wilderness. The hills unashamedly expose the bare bones of the earth, folded into complex patterns and a series of long sinuous lochs betray the evidence of geological faults, subsequently carved out by the grinding of massive glaciers. These scoured-out basins form the grain of the land but excellent tracks weave their way through glens and up over the bealachs at their heads giving good access to the summits, and what summits they are! The heart of this Great Wilderness is dominated by the Torridonian sandstone peak of Ruadh Stac Mor and the grey quartzite peak of A' Mhaighdean, arguably the remotest of all Scotland's Munros. And if these are the remotest Munros then neighbouring Beinn a’ Chaisgein Mor, 2808ft/856m, could well be amongst the most remote of the Corbetts.The Letterewe access debate began when a hillwalker cycled into the estate and left his bike at Carnmore when he went off to climb A’Mhaighdean, 967m/3173ft. On his return he discovered his bicycle tyres had been let down by an estate employee. The erstwhile owner of the estate, multimillionaire Paul van Vlissingen, had stated he didn’t welcome walkers and a number of notices around the estate made this very clear.There was some consternation amongst outdoor organisations but it was a hill-going member of the aristocracy who actually took the initiative. John Mackenzie has a series of titles including Earl of Cromartie and Clan Chief of the Mackenzies, but amongst climbers he was known as the author of the Scottish Mountaineering Clubs guide Rock & Ice climbs in Skye. He was incensed that access to the Letterewe estate with its famous crags like Carnmore might be in jeopardy and said so publicly. A story appeared in one newspaper stating that John intended leading a clan march onto van Vlissingen’s land in protest!That march never happened but what did follow were two years of detailed debate involving not just Mackenzie and van Vlissingen, but also representatives of numerous bodies including the Ramblers and the Mountaineering Council of Scotland. These discussions eventually produced The Letterewe Accord, which guaranteed walkers certain rights, and for the very first time anywhere in Britain a landowner had acknowledged that recreational users had rights to roam over his land. This Accord document was very important in the following discussions that eventually produced the current access provisions of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act. A'MhaighdeanI’m not sure if A’Mhaighdean will go down in history as the mountain that was central to the access debate but it will probably continue to be recognized as our remotest Munro, if for no other reason that master Munro-man Hamish Brown says so, (he describes A’Mhaighdean as “the least easily reached”) and his assertion was backed by Irvine Butterfield in his book The High Mountains of Britain and Ireland. Irvine reckoned that the roads at Kinlochewe, Poolewe and Dundonnell are all about 9 miles equi-distant.But A’Mhaighdean is notable for something else. A host of writers have suggested that it is the finest viewpoint of all the Munros. The view out along the length of the crag-fringed Fionn Loch to Loch Ewe and the open sea is simply unforgettable, across a landscape that is as close to ‘wilderness’ as anything we have in this country.I’m very aware of the emotive context of that word, particularly when we are describing a landscape that is primarily remote and empty of people, but the poet John Milton once defined wilderness as “a place of abundance”, a paradoxical definition which American philosopher and poet Gary Snyder suggests catches the very condition of energy and richness that is so often found in wild systems.“...all the incredible fecundity of small animals and plants, feeding the web. But from another side, wilderness has implied chaos, eros, the unknown, realms of taboo, the habitat of both the ecstatic and demonic. In both senses it is a place of archtypal power, teaching and challenge.”I like that last sentence of Snyder’s, because it is particularly relevant in this particular area - it’s not known as the Letterewe Wilderness for nothing. The high level route from the bothy at Shenavall around Beinn a’Chlaidheihh Sgurr Ban, Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair, Beinn Tarsuinn, A’Mhaighdean and Ruadh Stac Mor is not only a genuine mountain challenge but takes you into a landscape that ticks most of the wilderness definition boxes.I’ve climbed A’Mhaighdean a couple of times as part of that long rosary of Munros; once on my own and another time with an old ski instructor pal, Jeff Faulkner from Aviemore.Jeff and I had climbed An Teallach from Dundonnell and had carried our heavy backpacking gear over the steep sided Corrag Bhuidhe buttresses. We then descended steep ground to Shenavall where we spent the night. A river crossing heralded the next day’s hill bashing, and a long day it was traversing Beinn a’ Chlaidheimh, Sgurr Ban, Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair, Beinn Tarsuinn and A’Mhaighdean. We camped between the maiden and her northern neighbor Ruadh Stac Mor, before climbing the latter Munro first thing in the morning. And then it was the long walk-out to Poolewe…I’ve also climbed A’Mhaighdean from the marvellous oak woods of Loch Maree where there was once a thriving iron smelting industry; from the cathedral-like grandeur of the Fionn Loch below the steep crags of Beinn Airigh Charr, Meall Mheinnidh and Beinn Lair and from the empty quarter around lonely Lochan Fada before returning to Kinlochewe from the narrow gorge of Gleann Bianasdail. But even the simplest route, the most direct route to A’Mhaighdean and Ruadh Stac Mor is a classic, a memorable walk-in (you could use a mountain bike) and an ascent through a landscape that is as wild and formidable as any.

A'MhaighdeanI’m not sure if A’Mhaighdean will go down in history as the mountain that was central to the access debate but it will probably continue to be recognized as our remotest Munro, if for no other reason that master Munro-man Hamish Brown says so, (he describes A’Mhaighdean as “the least easily reached”) and his assertion was backed by Irvine Butterfield in his book The High Mountains of Britain and Ireland. Irvine reckoned that the roads at Kinlochewe, Poolewe and Dundonnell are all about 9 miles equi-distant.But A’Mhaighdean is notable for something else. A host of writers have suggested that it is the finest viewpoint of all the Munros. The view out along the length of the crag-fringed Fionn Loch to Loch Ewe and the open sea is simply unforgettable, across a landscape that is as close to ‘wilderness’ as anything we have in this country.I’m very aware of the emotive context of that word, particularly when we are describing a landscape that is primarily remote and empty of people, but the poet John Milton once defined wilderness as “a place of abundance”, a paradoxical definition which American philosopher and poet Gary Snyder suggests catches the very condition of energy and richness that is so often found in wild systems.“...all the incredible fecundity of small animals and plants, feeding the web. But from another side, wilderness has implied chaos, eros, the unknown, realms of taboo, the habitat of both the ecstatic and demonic. In both senses it is a place of archtypal power, teaching and challenge.”I like that last sentence of Snyder’s, because it is particularly relevant in this particular area - it’s not known as the Letterewe Wilderness for nothing. The high level route from the bothy at Shenavall around Beinn a’Chlaidheihh Sgurr Ban, Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair, Beinn Tarsuinn, A’Mhaighdean and Ruadh Stac Mor is not only a genuine mountain challenge but takes you into a landscape that ticks most of the wilderness definition boxes.I’ve climbed A’Mhaighdean a couple of times as part of that long rosary of Munros; once on my own and another time with an old ski instructor pal, Jeff Faulkner from Aviemore.Jeff and I had climbed An Teallach from Dundonnell and had carried our heavy backpacking gear over the steep sided Corrag Bhuidhe buttresses. We then descended steep ground to Shenavall where we spent the night. A river crossing heralded the next day’s hill bashing, and a long day it was traversing Beinn a’ Chlaidheimh, Sgurr Ban, Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair, Beinn Tarsuinn and A’Mhaighdean. We camped between the maiden and her northern neighbor Ruadh Stac Mor, before climbing the latter Munro first thing in the morning. And then it was the long walk-out to Poolewe…I’ve also climbed A’Mhaighdean from the marvellous oak woods of Loch Maree where there was once a thriving iron smelting industry; from the cathedral-like grandeur of the Fionn Loch below the steep crags of Beinn Airigh Charr, Meall Mheinnidh and Beinn Lair and from the empty quarter around lonely Lochan Fada before returning to Kinlochewe from the narrow gorge of Gleann Bianasdail. But even the simplest route, the most direct route to A’Mhaighdean and Ruadh Stac Mor is a classic, a memorable walk-in (you could use a mountain bike) and an ascent through a landscape that is as wild and formidable as any. Passing the Dubh Loch on the long walk-in from PooleweThe long walk-in is a fine way to court this particular maiden. (A’Mhaighdean can be translated as ‘the maiden’ although Peter Drummond, in his excellent Scottish Hill and Mountain Names, points out that in both Scots and Gaelic cultures a maiden is also the last sheaf of corn cut during the harvest. There are many Highland traditions associated with this last stook when, after a good harvest, it would be dressed to look like a young girl. You certainly notice a likeness to a sheaf when you look at the summit from the west.)The long walk-in from Poolewe allows you time to ease yourself gently into this marvelous landscape, by way of Kernsary and the Fionn Loch. Stay in a tent or use the bothy at Carnmore. Whatever way you approach these hills the undoubted highlight is the ascent of A’Mhaighdean from Carnmore.On one memorable ascent my wife and I walked in from Poolewe and camped close to the causeway between the Fionn Loch and the Dubh Loch. A’Mhaighdean’s ‘stook’-like summit dominated the view from the tent door. Nearby the house at Carnmore was locked up and I recalled Tom Weir’s stories about the Macrae family who once lived there. Over the years Tom got to know the family quite well and he was always made very welcome. That was probably in the nineteen-forties or fifties. Estate guests now use the house, although the nearby bothy is always available but be warned, it’s a little less than basic!We felt more comfortable in our tent and a memorable camp it turned out to be. The sunset, reflected on the waters of the Fionn Loch, was as spectacular as any I’ve seen, a slowly changing kaleidoscope of rich red and yellows and purples fading to a delicate pink. We lay outside the tent, dram in hand, desperate to tease out every last second, before the midges drove us inside to our sleeping bags.

Passing the Dubh Loch on the long walk-in from PooleweThe long walk-in is a fine way to court this particular maiden. (A’Mhaighdean can be translated as ‘the maiden’ although Peter Drummond, in his excellent Scottish Hill and Mountain Names, points out that in both Scots and Gaelic cultures a maiden is also the last sheaf of corn cut during the harvest. There are many Highland traditions associated with this last stook when, after a good harvest, it would be dressed to look like a young girl. You certainly notice a likeness to a sheaf when you look at the summit from the west.)The long walk-in from Poolewe allows you time to ease yourself gently into this marvelous landscape, by way of Kernsary and the Fionn Loch. Stay in a tent or use the bothy at Carnmore. Whatever way you approach these hills the undoubted highlight is the ascent of A’Mhaighdean from Carnmore.On one memorable ascent my wife and I walked in from Poolewe and camped close to the causeway between the Fionn Loch and the Dubh Loch. A’Mhaighdean’s ‘stook’-like summit dominated the view from the tent door. Nearby the house at Carnmore was locked up and I recalled Tom Weir’s stories about the Macrae family who once lived there. Over the years Tom got to know the family quite well and he was always made very welcome. That was probably in the nineteen-forties or fifties. Estate guests now use the house, although the nearby bothy is always available but be warned, it’s a little less than basic!We felt more comfortable in our tent and a memorable camp it turned out to be. The sunset, reflected on the waters of the Fionn Loch, was as spectacular as any I’ve seen, a slowly changing kaleidoscope of rich red and yellows and purples fading to a delicate pink. We lay outside the tent, dram in hand, desperate to tease out every last second, before the midges drove us inside to our sleeping bags. Approaching the summitWhile a superb stalker’s path traverses across the steep slopes of Sgurr na Lacainn from Carnmore and makes a tortuous route into the mountain’s north-east corrie we chose to scramble up the steep, stepped north-west ridge. The stalker’s path took us as far as Fuar Loch Mor from where we skirted the loch’s western bank and took to the rock. There was plenty of good, steep scrambling but all the real difficulties can be avoided. In essence, this was a stairway to heaven, a heaven with some of the best views imaginable – I truly believe the view from the summit of A’Mhaighdean is the best in the country.For such a rocky looking mountain the bare bluff summit of A’Mhaighdean comes as a bit of a surprise, but it makes for a fairly easy descent towards the high bealach above Fuar Loch Mor where a scramble takes you up steep broken slopes surprisingly easily to the summit of neighbouring Ruadh Stac Mor and its beautifully crafted stone trig-point.Back at the bealach, a superbly built stalker’s path eases its way downhill below the skirt of red screes which form the base of Ruadh Stac Mor, past the brooding Fuar Loch Mor and down over the high gneiss-patched moorland to the main Dundonnell to Poolewe track beside Lochan Feith Mhic-Illean.Now, as the legs began to tire, it took a bit of motivation to think of climbing the neighbouring Corbett of Beinn a’ Chaisgein Mor, but as we descended by the Fuar Loch Mor to the path junction we thought of the views from the summit of the Corbett, out along the length of the Fionn Loch to Loch Ewe and the outlines of Skye and the Hebrides shimmering on the western seas. We may even get a glimpse of Stac Pollaidh, hiding away in the north, peeping out between the bigger hills. It was enough to overcome our weariness and, as it turned out, was easier than we expected.From the path junction we simply climbed the broad east shoulder of Beinn a’ Chaisgein Mor to its rocky summit. The views made it all worthwhile and when we returned to our base at Carnmore camp food never tasted so good nor a sleeping bag more comfortable. We didn’t wait up for the sunset…