Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 22

April 25, 2011

Enigmatism

The Enigmatists of Fable are deep-minded scholars who study the Perilous Realm and try to understand its many mysteries. In our world we used to call such men and women natural philosophers. Now we call them scientists.

Enigmatists, like knights of the Errantry, roam far and wide through the lands of Story, but unlike knights-errant (or most readers of stories, for that matter), they aren't content to simply wander through a story and let it unfold as it will. Enigmatists will study a story, keep voluminous notes, gather specimens, make conjectures about what, how, and why the story is the way it is and what secrets it might hold.

There are enigmatists who specialize in the study of only one particular element of Story. For example the pratchetologists, who are experts in all things relating to tiny little people (there are many, many races of tiny little people in the Realm. You probably have some living in your walls. Most are harmless). Or the monocerologists, the Realm's experts on unicorns.

But this kind of specialization doesn't stop there. Even within these narrower fields of study there are subdivisions upon subdivisions. Within the field of monocerology itself there are enigmatists who restrict their research to the dietary habits of unicorns, which they study by collecting and examining the creature's droppings. And within that field there are those who study only the droppings of black unicorns. And then there are those who study only the droppings of one particular black unicorn named Trevor, who lives in Medicine Hat. As you can imagine, Trevor doesn't enjoy being followed around by packs of enigmatists eager to get a sample of his droppings, and he tends to be quite cranky and dangerous to approach. But enigmatists live for this kind of bracing adventure.

Then there are what are sometimes called the "true" Enigmatists, the ones who investigate and ponder Story itself: its ultimate nature and purpose. Why are there stories at all? What are stories really made of? (The most recent research seems to suggest that stories are made out of invisible, energy-bearing particles called narratons, that have strange properties, such as their tendency to collapse when one tries to measure their speed or direction) Is there any end to stories or do they go on forever? What was the very first story? The quandary that all such enigmatists face is that any answer to such questions will ultimately take the form of a story, and thus the answer will become its own question, like a snake biting its tale. (Pardon the pun. Enigmatists are also very fond of these).

And so it would seem there is no place one can stand "outside" the Realm and say what a story is without telling another one.

Published on April 25, 2011 11:43

April 19, 2011

Finding a form

"Children play with puppets, toy horses, or kites in order to get acquainted with the physical laws of the universe and with the actions that they will someday really perform. Likewise, to read fiction means to play a game by which we give sense to the immensity of things that happened, are happening, or will happen in the actual world. By reading narrative, we escape the anxiety that attacks us when we try to say something true about the world.

This is the consoling function of narrative---the reason people tell stories, and have told stories from the beginning of time. And it has always been the paramount function of myth: to find a shape, a form, in the turmoil of human experience."

Umberto Eco,

from Six Walks in the Fictional Woods

Published on April 19, 2011 13:42

April 15, 2011

The Barber of Edmonton

I go to a barber who has one of those old-fashioned little hole-in-the-wall barbershops in a strip mall. He's not an old guy, though, he's probably in his thirties and has a three-year-old son he likes to talk about. His name is Ash, and he's from Italy originally, from Milan I believe.

When I was in his shop the other day, we got to talking about this and that as we usually do. These conversations can go in all sorts of directions, I've found, because Ash likes to talk (a good trait for a barber to have, and I know because not every barber has it, and it's not a pleasant experience having your hair cut by someone who maintains a stony silence) and he'll weigh in on just about any subject. Not in a know-it-all or BS'ing kind of way, though. He's just curious about places and people.

So I was in Ash's barbershop (my son was getting his haircut, not me), and Ash was asking me how my latest book was coming along, and then he suggested that I write a book based on stories told to a barber. He said I wouldn't believe some of the stuff that people tell him when they're in the chair. Sometimes he gets the feeling that people are telling him things they've never told anyone else.

It has something to do with the fact that he is touching their hair, he said. That's a very personal thing. You have to be comfortable with the person who cuts your hair, he said. You have to feel you can trust them. And because people place that trust in him, it makes them more open to talking about what's going on in their lives.

I said I thought that sounded like a great idea, a book of stories told by people in the barberchair, and I asked him to give me an example of one of the good ones he's heard over the years. I guess I was hoping to get some juicy anecdotes that I could stash in my writing notebook for a rainy day. Ash hemmed and hawed about it but in the end he didn't spill any beans, and I admired him for it. He wasn't about to lightly toss out someone else's personal tale of woe just to provide me with some vicarious entertainment or schadenfreude.

He also told me that if I put the word barber in the title of my next book, it would be sure to sell a million copies. I'm thinking about it.

Published on April 15, 2011 13:47

April 6, 2011

To Destroy is to De-Story

There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you.

– Maya Angelou

The Bad Guy in The Shadow of Malabron is Malabron himself, the Night King. He calls himself the Lord of Story, and believes he is the right and true ruler of the entire Realm. Malabron's goal is to "eat" every story, so that only one story will remain: his own story, a nightmare of absolute power. If he succeeds in this he will obliterate the past, so that no one will even remember there were stories other than his. And he will destroy the future, so that no one will be able to imagine other possible stories that could be told, or lived.

While I was writing Shadow of Malabron, the word "destroy" often came up in scenes where the characters talk about Malabron's threat to the Realm. I am a fast typer but not always accurate, and I often found myself typing the word "destroy" as "destory." This annoyed me until I realized that this is exactly what tyrants do (in the real world as well as fantasy novels). When they set out to destroy opposition, or freedom, or independent thought, one of the things they go after is story. Take away someone's story, or their ability to tell their story, and you take away much of who they are and their freedom to imagine that things could be different. This is truly to de-story someone.

A real-world example: the absolute control that North Korea's dictator Kim Jong-il holds over the media – newspapers, television, radio and the internet. The people of this country are prevented from reading or hearing stories other than the official ones that the government puts forth. On television they are fed a steady diet of reports about their wonderful leader and all of the wonderful things he has been doing for their country. Dissent is punished, so no one dares tell their own alternate story of how things really are in that country.

The people of North Korea are being systematically "de-storyed."

Every government rules to some extent in similar ways, as do the giant corporations that want us all to buy the same products, that is, live the same story, a story that they impose on us rather than one we tell for ourselves. (Yes, there still are big bad giants in the world.)

Any kind of deliberate human destruction is also a destroying, in one way or another. When a forest is cleared, countless life "stories" of the creatures that live their may be lost. When a child soldier dies in war, his or her story is over before it has barely begun.

De-storying imposes an absolute "The End" on stories that still might have grown in unexpected ways. Human beings are creatures that tell stories. We live and breathe stories. Truly we need them to survive. To be prevented from telling your story is, as Maya Angelou points out, a great agony. A killing silence.

So now when I type the word "destroy" and it comes out "destory," I still correct it, but the mistake serves to remind me of the deep connection between destruction and the loss of story.

Published on April 06, 2011 11:36

March 28, 2011

A Very Brief Tale

The time-eater smacked his lips.

"Those minutes and hours were delicious," he said, and lifted his empty plate.

"May I have seconds?"

"Those minutes and hours were delicious," he said, and lifted his empty plate.

"May I have seconds?"

Published on March 28, 2011 20:55

March 20, 2011

The Boy and His Voice: A Tale

A boy woke one morning to find he had lost his voice.

He went to his mother and father and tried to tell them what had happened to him. He clutched his throat and waved his arms to show them that his voice was gone. His mouth opened and closed like the mouth of a fish out of water.

"You're always so careless with your things," they shouted at him, shaking their heads. "Now you gone and lost your voice, too?"

The boy's father took him to the wise old woman who lived alone in a house by the sea, a house made of the bones of a beached whale. She looked at the boy, made him open his mouth, and looked down his throat with a phosphorescent stone on a string.

"You haven't lost your voice," the wise old woman said to the boy. "Someone has taken it."

"Who would do such a thing?" the boy's father demanded.

"Who he is I do not know," the old woman said, "but I hear the echo of his swift feet running away to the great forest. If you wish to find your voice, you must go there, boy. Search everywhere, even in the unlikeliest places, for this thief is clever and will have hidden your voice where you least expect it to be. And you must make this journey alone, because you will need to make friends with silence if you ever hope to find your voice and return."

The boy's father gave him a knife and a pouch with nine coins which had been saved for a rainy day. His mother gave him a loaf of bread, a hunk of cheese, and a flask of water. The boy left his home by the sea and walked inland, and soon he came to the great forest. He walked under the mighty trees whose green branches swayed in the wind, and he thought it was something like walking under the waves of the sea.

Days went by. The boy looked everywhere for his voice. Under stones and dry leaves, in hollow trees and old wasp nests, by the sides of loudly rushing streams and in single drops of water. The boy's food ran out, and with his coins he bought more food in the villages he passed through. Then the coins ran out, and it was then that silence, as the old woman had told him, became his good friend.

One night the boy came to a clearing. The moon was full and high in the sky. The crickets were chirping as they did every night. It was a sound the boy had heard so often he had stopped listening to it, but tonight, because his belly was empty and he had nothing left but silence, he listened to the crickets, and deep within their song he heard his own voice once again.

The boy searched the clearing, and found a tunnel hidden under a rotting log. He crouched and made his way slowly down the tunnel, which went a long way under the earth, until at last he came to the hall of the Cricket King. Hundreds of crickets, singing as one, were gathered around their monarch, who sat on his toadstool throne. He had a goblet of moonbeam wine in one hand, a sceptre in another hand, and a golden ball in a third (he had six hands altogether, which is very ... um ... handy when you're a king with many subjects to rule).

When the boy appeared, the crickets fell silent.

The Cricket King looked at the boy and smiled.

"We've dressed your voice up as one of us," the king said. "I believe it's quite happy in our choir. But if you can guess which one of our singers is really your voice, you may take it and go unharmed."

The Cricket King raised a hand (one of the six that wasn't holding anything) and the hundreds of crickets began to sing. The boy walked among them, and because he had made friends with silence, it stood by him now and would not let him be carried away by the frenzied din. That was how he was able to hear his own voice again, in the midst of the chorus of crickets. He found his voice and threw his arms around it. His voice struggled a while, then at last it peeled off its cricket disguise and lay shivering in his arms.

"Very good!" the Cricket King cried, clapping several of his hands. "Now you must go, boy, before we decide to keep you longer than you would care for."

With his voice the boy thanked the Cricket King (his mother had told him you must always thank the mighty for the trouble they cause -- in their minds it's a great honour), then he hastily left the underground kingdom with its roaring sea of crickets.

When he had come safely home at last, the boy rarely used his voice to speak with. Instead he shaped it into a ring and gave it to his silence to wear on its little finger.

-- Adapted from a poem by Federico Garcia Lorca

Published on March 20, 2011 16:15

February 28, 2011

walking in the woods

This isn't a story, it's a poem. Or maybe it's both.

The boy walking in the woods

hears birdcall and leaf hiss

these sounds outside of him

and within him too

the world, a movement

back and forth between inside

and out

and his thoughts

are walking too

like ghosts in a

mathematical forest

sometimes a thought

so new and strange

it takes him a few steps to

catch up to it.

He wonders

have I walked into another world?

The woods

never say yes

or no.

The boy walking in the woods

hears birdcall and leaf hiss

these sounds outside of him

and within him too

the world, a movement

back and forth between inside

and out

and his thoughts

are walking too

like ghosts in a

mathematical forest

sometimes a thought

so new and strange

it takes him a few steps to

catch up to it.

He wonders

have I walked into another world?

The woods

never say yes

or no.

Published on February 28, 2011 09:47

January 28, 2011

Story, Time

Every story has its own time. I may not visit a particular story for many years, but when I do go back I usually find myself right back at the beginning, as if time has not passed there at all. Or if I left the story before it was over, I can usually find my way back to the place (or rather time) I left, and find myself right in the midst of the same events that were happening before.

And another curious thing is that a lot of time can go by in a story – hours, days, even years – but when I leave the story and return to my own world, I usually find that only a short time has passed. And this can happen even if I don't visit the story itself in person. Even the spell of a good storyteller's voice can work this strange magic.

The opposite can be true as well, although it has happened to only a few travelers I know: that one might spend only what seem a few brief moments or hours in a story and then return to one's own world to discover that years have gone by.

Time can be strange and unpredictable within a story, too. It can slow down to a crawl, or stand still, or hours, days or years can be leapt over suddenly. One can find oneself going backwards in time, too, or catch glimpses of moments long past. One might discover that there are many different kinds of time, and they are all ways of seeing, of being in the world.

Visiting the realm of Story can teach us a lot about time. Most of us live in a world where time is thought of as a commodity, a resource, a possession. We think of time as something we have a certain amount of, and that if we're not careful our time can be taken away from us by others. We act as if time is something we can save, like money in a bank, and that we should never waste it. Michael Ende's wise and lovely novel Momo describes what happens to the world when we think of time this way. We discover that we haven't saved anything, that in fact we've lost something precious.

In our busy, measured, time-obsessed world, we imagine time goes in only one direction, toward the future, at a steady, ticking pace. And many of us believe that if we "spend" our time carefully now, and stick to a strict regimen of clocktime, we will earn a future in which we no longer have to keep track of the seconds and minutes and can just relax and enjoy our "free" time. But by then we might find that we've become so fixed in our idea of saving time that we can no longer just live it. We will have forgotten that time was always free, and never belonged to anyone.

As the narrator of Momo says, "Time is life itself, and life resides in the human heart."

Published on January 28, 2011 10:42

January 14, 2011

Kyning Rore

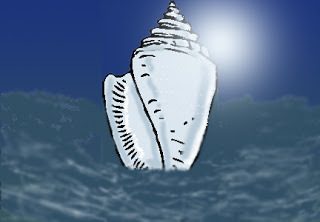

Kyning Rore is a university for mages, located on a small island off the eastern coast of the Perilous Realm, in the Sea of Mists.

The island was shaped by magecraft over many years into the likeness of a great spiraling seashell of white stone. Within the seashell are the many classrooms, laboratories, libraries and dormitories of the university. The seashell can be seen for miles around, even at night or when the mists are thick upon the sea, for the stonework of the walls gives off a phosphorescent glow in the dark.

The mages who teach at Kyning Rore come from all over the realm, as do those who hope to become students. Anyone may apply to study at the Rore, and tuition and board are free, but of the many who come there to learn magecraft, most sail away soon after, having discovered that they have not the gifts or the dogged determination to carry on with a program of study that is rigorous, demanding, and sometimes leads to unpleasant revelations about oneself and one's limitations.

Kyning Rore was once a remote, forbidding place where only the daring, hardy few came to learn the mage's art. The food at the dining hall was meager, tasteless fare, and each student was assigned a small, sparsely furnished cell (there is no other word for these cold stone closets). In winter these rooms could be bitterly cold. There have been many changes over the years, however, as the university became well-known for the quality of its instruction. More and more students flocked there, the food got better, the rooms more comfortable, and it has even been suggested that the curriculum is no longer as difficult or challenging as it once was, that students now come to the island not so much to learn the craft as to acquire the glittering reputation of having been a student at the Rore.

Many famous mages have trained at Kyning Rore, and unfortunately a few infamous ones as well, who took what they learned and used it to deceive and control others. A Master's degree from Kyning Rore, they say, is no longer a guarantee that the mage who carries it still follows the mage's oath to serve others and do no harm.

Published on January 14, 2011 10:43

December 15, 2010

Yule

From the Old English word geol or geola, meaning "Christmas Day, Christmastide." But this Old English word comes from jol, an Old Norse word for a feast (of the pagan variety). A similar word, giuli, referred to a two-month winter "season" that was roughly the same period as the December and January of the Romans. And the Old Norse word may have been a borrowing from an Old French word, jolif, meaning something nice, festive or … jolly. The word was revived in the 19th century, to give a unique name to the tradition of a "Merry Old English" Christmas.

Yule is also a country in the Perilous Realm, far to the north, in the Snowlands. It is also called The Kingdom of the Fir Trees. It is said that a great loremaster lives there, who is known to ride about on a sleigh pulled by the great antlered deer called tarand, bringing gifts and good cheer to everyone, to help them through the long dark winter, which in that country is all year round. Yule is, in fact, the place where Christmas (and its ancient pagan forebears) lives on always. To live there you'd have to get used to a steady diet of plum pudding and wassail.

As I look out my window now, I see snow falling. Looks like it will fall all day. I can almost imagine I live in the land of Yule. Time to go make some wassail.

Yule is also a country in the Perilous Realm, far to the north, in the Snowlands. It is also called The Kingdom of the Fir Trees. It is said that a great loremaster lives there, who is known to ride about on a sleigh pulled by the great antlered deer called tarand, bringing gifts and good cheer to everyone, to help them through the long dark winter, which in that country is all year round. Yule is, in fact, the place where Christmas (and its ancient pagan forebears) lives on always. To live there you'd have to get used to a steady diet of plum pudding and wassail.

As I look out my window now, I see snow falling. Looks like it will fall all day. I can almost imagine I live in the land of Yule. Time to go make some wassail.

Published on December 15, 2010 09:54