Karl Shuker's Blog, page 6

December 23, 2022

PERUVIAN BANDICOOTS, UNDISCOVERED TAPIRS, ZEBRA-STRIPED CARROT CREATURES, AND OTHER NEOTROPICAL NOVELTIES, COURTESY OF LEQUANDA & THI��BAUT

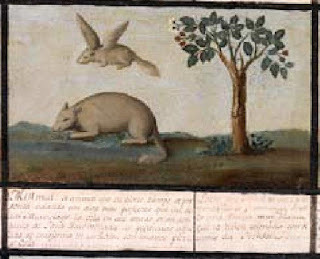

Isthis a bilby I see before me ��� in Peru?? (public domain)

Isthis a bilby I see before me ��� in Peru?? (public domain)

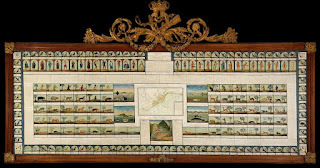

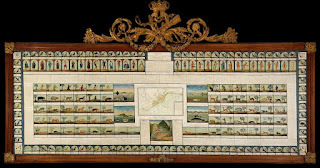

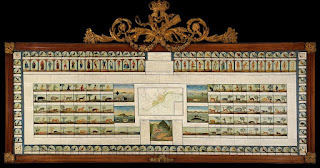

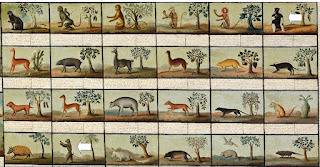

In my previous ShukerNature blog article(click hereto access it), I documented two unexpected creatures depicted in a magnificentmural-format pictorial encyclopaedia entitled Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geografica del Reyno del Peru('Painting of the Natural, Civil and Geographical History of the Kingdom ofPeru'), or QHNCGRP for convenience hereafterin this present article. Consisting of numerous miniature oil paintings andaccompanying text on a wood panel, it measures a very impressive 128x 45.25 inches (325 x 115 cm).

Completed in Madrid, Spain, in 1799 andnow on display at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid (Spain'snational museum of natural history), which has produced an exquisite, lavishly-illustrated website devoted specificallyto it (click here),QHNCGRP was authored by Basque-bornbut (for three decades) Peru-based scholar Jos�� Ignacio Lequanda, whocommissioned French artist Louis Thi��baut to produce the 194 paintingsillustrating it. As noted above, most of these are miniatures, with tiny butvoluminous text by Lequanda accompanying all of the 160 miniatures depictingfauna and flora of Peru or its South American environs.

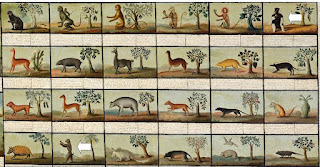

The vast majority of these miniaturesdepict readily-recognisable Neotropical species, including a large spottedrodent named the paca, a South American zorro or 'fox' (actually a species of Dusicyon canid), an otter, tapir,manatee, various monkeys, trumpeter bird, cock of the rock, spoonbill,hummingbird, Humboldt's penguin, skunk, caiman, giant anteater, fulgorid lantern-fly,llama, vicuna, armadillos, coati, and opossum, to mention but a few.

Viewof QHNCGRP in its entirety ��� click toenlarge for viewing purposes (�� Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales ���reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Viewof QHNCGRP in its entirety ��� click toenlarge for viewing purposes (�� Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales ���reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Also present, however, are certaindecidedly mystifying zoological portraits, such as that of a dramaticallyout-of-place Madagascan black-and-white ruffed lemur and one of a putativeliving ground sloth, both of which I documented in my previous QHNCGRP article.

Since writing that, I have been payingfurther close attention to this marvelous pictorial menagerie, and I've spottedseveral additional examples included within it that are nothing if not curiousor controversial, for various differing but equally interesting reasons. Sohere they are ��� make of them what you will!

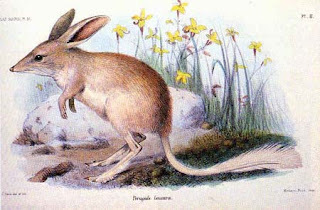

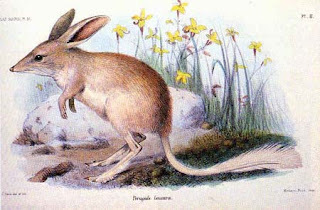

Take, for instance, the very distinctivecreature portrayed in the QHNCGRPminiature that opens this present ShukerNature article. Whereas I am not awareof any South American mammal matching its morphology (Lequanda claimed it to be a vizcacha, and others have suggested the latter rodent's relative the chinchilla, but these bear little ��� in the case of the chinchilla ��� or no ��� in the case of the vizcacha ��� resemblance to it, I am aware that it does beara remarkable similarity to a certain species of exclusively Australianmarsupial. Namely, the lesser bilby (aka lesser rabbit-eared bandicoot) Macrotis leucura.

Mysterybig-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRPmammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist OldfieldThomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes andMarsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Mysterybig-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRPmammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist OldfieldThomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes andMarsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Certainly, its long snout, lengthy plumedtail, and very sizeable ears all correspond very closely to those of the latterspecies. True, its forelimbs are much the same size as its hind ones, whereasthose of the lesser bilby are shorter, and its fur is white rather than brownlike the bilby's. However, the limb discrepancy may simply be an error onThi��baut's part, especially if his subject's preserved skin had becomedistorted via shrinkage. Moreover, preserved skins frequently blanch if exposedtoo long to light (the taxiderm thylacine that was on public display inLondon's Natural History Museum when I visited in 2014, for example, was sofaded, predominantly cream in colour all over, that its diagnostic stripes hadvanished).

Deriving its English name from its verylarge, slender, rabbit-like ears, and characterized by its tail's long whitehairy plume, the lesser bilby was once native to the deserts of centralAustralia, but has not been conclusively sighted since the 1950s, so is nowdeemed extinct. Back when QHNCGRP wascreated, however, it was still in existence, with preserved specimens inmuseums.

As apparently happened with the ruffedlemur, is it possible, therefore, that Lequanda and/or Thi��baut saw a museum specimenof the lesser bilby at Madrid's celebrated Royal Natural History Cabinet(founded in 1771, opened to the public in 1776, and whose contents were veryfamiliar to Lequanda), or even elsewhere, and mistakenly assumed that it was aNeotropical species? Or might Thi��baut have based his miniature upon somepre-existing artwork by another artist? There is a notable QHNCGRP���linked precedent for this latter possibility.

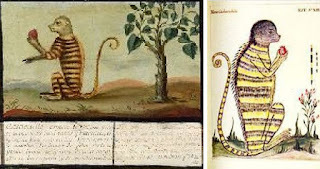

Thi��baut'szebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey(top left), Compa��on's earlier artwork upon which Thi��baut's was based (top right),and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (��Eric Kilby/Wikipedia ���

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Thi��baut'szebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey(top left), Compa��on's earlier artwork upon which Thi��baut's was based (top right),and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (��Eric Kilby/Wikipedia ���

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

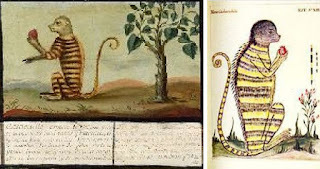

One of the several monkeys depicted asminiatures in QHNCGRP by Thi��baut isthe extraordinary-looking striped example shown above. Its bold zebra-like bodyand limb markings instantly set it apart from any currently-known monkeyspecies, as does the mid-dorsal row of spines running down its back. These arealso alluded to by Lequanda, in his accompanying text. He referred to this fascinatingfasciated creature as a casacuillo, and also mentioned that it lived upon fruit.

Rather than basing his illustration of thiscasacuillo upon first-hand observations of a living or preserved animal,however, Thi��baut used as his inspiration a pre-existing 18th-Centuryillustration. Namely, a water-colour prepared some years earlier with 1,410others for inclusion in the Codex Mart��nezCompa��on, a sumptuous nine-volume manuscript made by Baltasar Jaime Mart��nezCompa��on, Bishop of Trujillo, Peru. This water-colour is also shown here, forcomparison purposes alongside Thi��baut's oil painting.

Moreover, according to writer CarmenMart��nez, writing in an online article from June 2021 devoted to QHNCGRP (click hereto access it), this creature is not a monkey at all, but is instead a SouthAmerican tree porcupine or coendou, of which there are many species, allsporting a prehensile tail. However, to me it looks no more like a tree porcupinethan it does a monkey! Coendous are not striped and their fine spines arepresent profusely over their entire body, not merely along their back. So I amunconvinced by this identification.

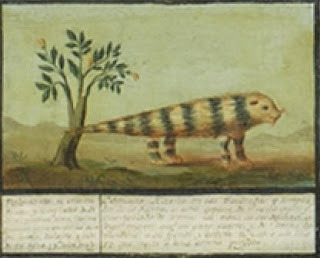

Astriped carrot on legs!! Another of Tri��baut's bemusing mystery beasts includedby him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

Astriped carrot on legs!! Another of Tri��baut's bemusing mystery beasts includedby him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

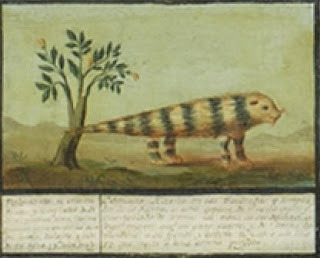

And speaking of zebra-patterned mysterybeasts depicted in QHNCGRP, what arewe to make of the example shown above? It looks for all the world like a stripedcarrot on legs! It seems to be furry, eared, and whiskered, and is included in the left-hand block of 30mammal miniatures (according to Lequanda, moreover, it is, once again, a coendou!), so we must assume that it is indeed mammalian ��� or shouldwe?

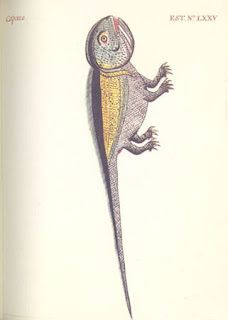

After all, also included in this sameblock of miniatures is the following bizarre beast, popularly if improbably(?)deemed to be a portrait of an iguana according to various sources consulted byme

Yet this latter beast is itself a majormystery. For it seems to possess a stiff pointed tail wholly unlike the highlyflexible tail of an iguana, as well as long curved fangs emerging from itsjaws, and what looks like a pair of wings pressed tightly against its flanks! Apparently, like the striped monkey/coendou illustration, Thi��baut based his miniature upon one from the Codex Mart��nezCompa��on that was labelled as an iguana. Really??

Asupposed iguana depiction by Thi��baut in QHNCGRP(above) and the original version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

Asupposed iguana depiction by Thi��baut in QHNCGRP(above) and the original version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

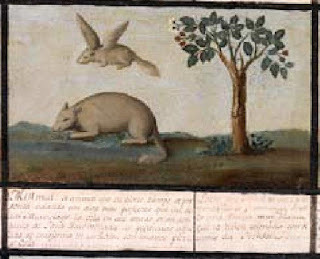

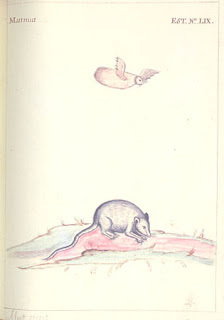

Most improbable of all, however, mustsurely be the next example presented here. What on earth (or in the air!) isthis extraordinary squirrel-like entity that sports not only two pairs of limbsand a bushy tail but also a pair of wings ��� and which are clearly functional,given that Thi��baut has portrayed it flying above a somewhat larger, rodent-likemammal in the same miniature?

Might it be the inaccurate result ofThi��baut painting not from direct observation of some physical specimen, butinstead merely from a verbal description of a flying squirrel? True, the name ofthese rodents is something of a misnomer, seeing that they become airborne notwith the assistance of wings but instead via a pair of gliding membranes (patagia),linking their wrist and ankle on each side of their body. But if a verbaldescription of such a creature does not make this distinction clear to anartist seeking to depict it, the result might well be an illustration of asquirrel-like creature boasting a pair of bona fide wings.

Yet even if that were true, there is stilla fundamental problem in applying it as an explanation for this aerial anomaly asportrayed here, because although flying squirrels are widely distributed inNorth America, they do not occur anywhere in South America. So why wouldThi��baut have depicted one in QHNCGRP?Yet another instance of someone wrongly assuming that a given creature isNeotropical when it definitely is not? Having said that, Thi��baut's illustration is yet again a copy of one from the Codex Mart��nezCompa��on, but in that version the flying entity looks far more like a bird than a mammal, so why did Thi��baut convert it into one in his copied version? Conversely, at least according to Lequanda's accompanying description of it in QHNCGRP, it is indeed a rodent with wings, and is referred to by him as a mutmut. All very strange!

Thi��baut'sbewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP(above) and the original bird-like version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

Thi��baut'sbewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP(above) and the original bird-like version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

My concern with the ostensiblyunidentifiable mystery creatures from QHNCGRPdocumented by me here is that, as already noted, most of the animals depictedin it by Thi��baut are readily recognisable. So as those were all accuratelyrepresented by him, why should the mystery beasts here not be too, unless he was indulging in some sly humour at Lequanda's expense, perhaps? Yet if they are accurate representations, why can wenot identify them?

Might at least some of them not havearisen through misapprehensions regarding the origins of specimens utilized assubjects, or even as a result of poor verbal descriptions of such, but insteadbe bona fide native Neotropical species that have become extinct before everbecoming known to European scientists, so their morphological appearance iswholly unfamiliar to us?

The last anomalous animal to beconsidered here may provide key evidence that some of Thi��baut's miniaturesdepict significant creatures that were still unknown to science at the timewhen he depicted them.

Thesupposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP(public domain).

Thesupposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP(public domain).

Just a few hours after I posted myprevious QHNCGRP-themed ShukerNaturearticle, on 22 December 2022, I received a very interesting, thought-provokingcomment from a reader with the Google username Andrew, and which I duly postedbeneath my article. It concerns the QHNCGRPminiature of what is officially assumed to be a specimen of the lowland (Brazilian)tapir Tapirus terrestris, the largestspecies of native mammal known to be alive today in South America, andoccurring widely here, including in Peru. Here is Andrew's comment:

Thi��baut's depiction of thetapir looks like it could have been based on descriptions of thethen-undiscovered mountain tapir, rather than the lowland species. It has nocrest, its coat is almost black with a slight chestnut tint, and it seems to havewhite lips.

Smaller and darker in colour than thelowland tapir, the mountain tapir T.pinchaque is a very distinctive species that is indeed uncrested andwhite-lipped. It is also noticeably woolly, and looking at the tapir miniature inclose-up its body surface does appear to be hairy. Moreover, of particularhistorical note is that this species, which is indeed native to Peru (occurringin its far north's montane cloud forests), was not formally described byscience until 1829 ��� 30 years after the creation of QHNCGRP.

A lowlandtapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (�� Dr Karl Shuker / (�� RichardSifry/Wikipedia ���

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

A lowlandtapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (�� Dr Karl Shuker / (�� RichardSifry/Wikipedia ���

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

In short, if the tapir miniature in QHNCGRP actually depicts a mountaintapir rather than a lowland tapir, this means that Thi��baut had portrayed amajor mammalian species three decades before its official discovery. This in turn begs the question: what specimenwas utilized by Thi��baut as the subject for his illustration?

Whichever it was, and wherever it was,its taxonomic significance as representing a dramatic new species had clearlynot been recognized or appreciated by scientists of the day.

As I have revealed many times in my trioof books on new and rediscovered animals, this is a sad situation that has occurredcountless times down through the centuries, with obscure museum specimens havingbeen long overlooked before belatedly receiving serious attention, only forthem then to be revealed as extraordinary new species whose existence had neverpreviously even been suspected, let alone confirmed. So the potential exampledocumented above has plenty of precedents, that's for certain!

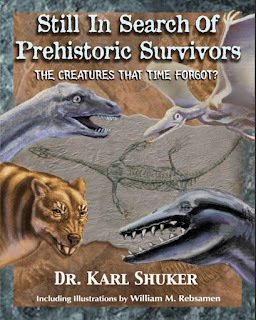

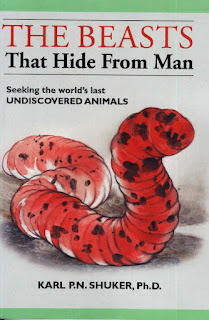

Mythree books on new and rediscovered animals (�� Dr KarlShuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)

Mythree books on new and rediscovered animals (�� Dr KarlShuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)

PERUVIAN BANDICOOTS, UNDISCOVERED TAPIRS, ZEBRA-STRIPED CARROT CREATURES, AND OTHER NEOTROPICAL NOVELTIES, COURTESY OF LEQUANDA & THIÉBAUT

Is this a bilby I see before me – in Peru?? (public domain)

Is this a bilby I see before me – in Peru?? (public domain)

In my previous ShukerNature blog article (click hereto access it), I documented two unexpected creatures depicted in a magnificent mural-format pictorial encyclopaedia entitled Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geografica del Reyno del Peru('Painting of the Natural, Civil and Geographical History of the Kingdom of Peru'), or QHNCGRP for convenience hereafter in this present article. Consisting of numerous miniature oil paintings and accompanying text on a wood panel, it measures a very impressive 128 x 45.25 inches (325 x 115 cm).

Completed in Madrid, Spain, in 1799 and now on display at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid (Spain's national museum of natural history), which has produced an exquisite, lavishly-illustrated website devoted specifically to it (click here), QHNCGRP was authored by Basque-born but (for three decades) Peru-based scholar José Ignacio Lequanda, who commissioned French artist Louis Thiébaut to produce the 194 paintings illustrating it. As noted above, most of these are miniatures, with tiny but voluminous text by Lequanda accompanying all of the 160 miniatures depicting fauna and flora of Peru or its South American environs.

The vast majority of these miniatures depict readily-recognisable Neotropical species, including a large spotted rodent named the paca, a South American zorro or 'fox' (actually a species of Dusicyon canid), an otter, tapir, manatee, various monkeys, trumpeter bird, cock of the rock, spoonbill, hummingbird, Humboldt's penguin, skunk, caiman, giant anteater, fulgorid lantern-fly, llama, vicuna, armadillos, coati, and opossum, to mention but a few.

View of QHNCGRP in its entirety – click to enlarge for viewing purposes (© Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

View of QHNCGRP in its entirety – click to enlarge for viewing purposes (© Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Also present, however, are certain decidedly mystifying zoological portraits, such as that of a dramatically out-of-place Madagascan black-and-white ruffed lemur and one of a putative living ground sloth, both of which I documented in my previous QHNCGRP article.

Since writing that, I have been paying further close attention to this marvelous pictorial menagerie, and I've spotted several additional examples included within it that are nothing if not curious or controversial, for various differing but equally interesting reasons. So here they are – make of them what you will!

Take, for instance, the very distinctive creature portrayed in the QHNCGRPminiature that opens this present ShukerNature article. Whereas I am not aware of any South American mammal matching its morphology, I am aware that it bears a remarkable resemblance to a certain species of exclusively Australian marsupial – namely, the lesser bilby (aka lesser rabbit-eared bandicoot) Macrotis leucura.

Mystery big-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRPmammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist Oldfield Thomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes and Marsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Mystery big-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRPmammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist Oldfield Thomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes and Marsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Certainly, its long snout, lengthy plumed tail, and very sizeable ears all correspond very closely to those of the latter species. True, its forelimbs are much the same size as its hind ones, whereas those of the lesser bilby are shorter, and its fur is white rather than brown like the bilby's. However, the limb discrepancy may simply be an error on Thiébaut's part, especially if his subject's preserved skin had become distorted via shrinkage. Moreover, preserved skins frequently blanch if exposed too long to light (the taxiderm thylacine that was on public display in London's Natural History Museum when I visited in 2014, for example, was so faded, predominantly cream in colour all over, that its diagnostic stripes had vanished).

Deriving its English name from its very large, slender, rabbit-like ears, and characterized by its tail's long white hairy plume, the lesser bilby was once native to the deserts of central Australia, but has not been conclusively sighted since the 1950s, so is now deemed extinct. Back when QHNCGRP was created, however, it was still in existence, with preserved specimens in museums.

As apparently happened with the ruffed lemur, is it possible, therefore, that Lequanda and/or Thiébaut saw a museum specimen of the lesser bilby at Madrid's celebrated Royal Natural History Cabinet (founded in 1771, opened to the public in 1776, and whose contents were very familiar to Lequanda), or even elsewhere, and mistakenly assumed that it was a Neotropical species? Or might Thiébaut have based his miniature upon some pre-existing artwork by another artist? There is a notable QHNCGRP–linked precedent for this latter possibility.

Thiébaut's zebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey (top left), Compañon's earlier artwork upon which Thiébaut's was based (top right), and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (© Eric Kilby/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Thiébaut's zebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey (top left), Compañon's earlier artwork upon which Thiébaut's was based (top right), and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (© Eric Kilby/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

One of the several monkeys depicted as miniatures in QHNCGRP by Thiébaut is the extraordinary-looking striped example shown above. Its bold zebra-like body and limb markings instantly set it apart from any currently-known monkey species, as does the mid-dorsal row of spines running down its back. These are also alluded to by Lequanda, in his accompanying text. He referred to this fascinating fasciated creature as a casacuillo, and also mentioned that it lived upon fruit.

Rather than basing his illustration of this casacuillo upon first-hand observations of a living or preserved animal, however, Thiébaut used as his inspiration a pre-existing 18th-Century illustration. Namely, a water-colour prepared some years earlier with 1,410 others for inclusion in the Codex Martínez Compañon, a sumptuous nine-volume manuscript made by Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañon, Bishop of Trujillo, Peru. This water-colour is also shown here, for comparison purposes alongside Thiébaut's oil painting.

Moreover, according to writer Carmen Martínez, writing in an online article from June 2021 devoted to QHNCGRP (click hereto access it), this creature is not a monkey at all, but is instead a South American tree porcupine or coendou, of which there are many species, all sporting a prehensile tail. However, to me it looks no more like a tree porcupine than it does a monkey! Coendous are not striped and their fine spines are present profusely over their entire body, not merely along their back. So I am unconvinced by this identification.

A striped carrot on legs!! Another of Triébaut's bemusing mystery beasts included by him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

A striped carrot on legs!! Another of Triébaut's bemusing mystery beasts included by him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

And speaking of zebra-patterned mystery beasts depicted in QHNCGRP, what are we to make of the example shown above? It looks for all the world like a striped carrot on legs! It seems to be furry, eared, and whiskered, and is included in the left-hand block of 30 mammal miniatures, so we must assume that it is indeed mammalian – or should we?

After all, also included in this same block of miniatures is the following bizarre beast, popularly if improbably(?) deemed to be a portrait of an iguana according to various sources consulted by me

Yet this latter beast is itself a major mystery. For it seems to possess a stiff pointed tail wholly unlike the highly flexible tail of an iguana, as well as long curved fangs emerging from its jaws, and a pair of wings pressed tightly against its flanks!

A supposed iguana depiction by Thiébaut in QHNCGRP(public domain)

A supposed iguana depiction by Thiébaut in QHNCGRP(public domain)

Most improbable of all, however, must surely be the next example presented here. What on earth (or in the air!) is this extraordinary squirrel-like entity that sports not only two pairs of limbs and a bushy tail but also a pair of wings – and which are clearly functional, given that Thiébaut has portrayed it flying above a somewhat larger, rodent-like mammal in the same miniature?

Might it be the inaccurate result of Thiébaut painting not from direct observation of some physical specimen, but instead merely from a verbal description of a flying squirrel? True, the name of these rodents is something of a misnomer, seeing that they become airborne not with the assistance of wings but instead via a pair of gliding membranes (patagia), linking their wrist and ankle on each side of their body. But if a verbal description of such a creature does not make this distinction clear to an artist seeking to depict it, the result might well be an illustration of a squirrel-like creature boasting a pair of bona fide wings.

Yet even if that were true, there is still a fundamental problem in applying it as an explanation for this aerial anomaly as portrayed here, because although flying squirrels are widely distributed in North America, they do not occur anywhere in South America. So why would Thiébaut have depicted one in QHNCGRP? Yet another instance of someone wrongly assuming that a given creature is Neotropical when it definitely is not?

Thiébaut's bewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP(public domain)

Thiébaut's bewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP(public domain)

My concern with the ostensibly unidentifiable mystery creatures from QHNCGRPdocumented by me here is that, as already noted, most of the animals depicted in it by Thiébaut are readily recognisable. So as those were all accurately represented by him, why should the mystery beasts here not be too? Yet if they are accurate representations, why can we not identify them?

Might at least some of them not have arisen through misapprehensions regarding the origins of specimens utilized as subjects, or even as a result of poor verbal descriptions of such, but instead be bona fide native Neotropical species that have become extinct before ever becoming known to European scientists, so their morphological appearance is wholly unfamiliar to us?

The last anomalous animal to be considered here may provide key evidence that some of Thiébaut's miniatures depict significant creatures that were still unknown to science at the time when he depicted them.

The supposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP (public domain).

The supposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP (public domain).

Just a few hours after I posted my previous QHNCGRP-themed ShukerNature article, on 22 December 2022, I received a very interesting, thought-provoking comment from a reader with the Google username Andrew, and which I duly posted beneath my article. It concerns the QHNCGRPminiature of what is officially assumed to be a specimen of the lowland (Brazilian) tapir Tapirus terrestris, the largest species of native mammal known to be alive today in South America, and occurring widely here, including in Peru. Here is Andrew's comment:

Thiébaut's depiction of the tapir looks like it could have been based on descriptions of the then-undiscovered mountain tapir, rather than the lowland species. It has no crest, its coat is almost black with a slight chestnut tint, and it seems to have white lips.

Smaller and darker in colour than the lowland tapir, the mountain tapir T. pinchaque is a very distinctive species that is indeed uncrested and white-lipped. It is also noticeably woolly, and looking at the tapir miniature in close-up its body surface does appear to be hairy. Moreover, of particular historical note is that this species, which is indeed native to Peru (occurring in its far north's montane cloud forests), was not formally described by science until 1829 – 30 years after the creation of QHNCGRP.

A lowland tapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (© Dr Karl Shuker / (© Richard Sifry/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

A lowland tapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (© Dr Karl Shuker / (© Richard Sifry/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

In short, if the tapir miniature in QHNCGRP actually depicts a mountain tapir rather than a lowland tapir, this means that Thiébaut had portrayed a major mammalian species three decades before its official discovery. This in turn begs the question: what specimen was utilized by Thiébaut as the subject for his illustration?

Whichever it was, and wherever it was, its taxonomic significance as representing a dramatic new species had clearly not been recognized or appreciated by scientists of the day.

As I have revealed many times in my trio of books on new and rediscovered animals, this is a sad situation that has occurred countless times down through the centuries, with obscure museum specimens having been long overlooked before belatedly receiving serious attention, only for them then to be revealed as extraordinary new species whose existence had never previously even been suspected, let alone confirmed. So the potential example documented above has plenty of precedents, that's for certain!

My three books on new and rediscovered animals (© Dr Karl Shuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)

My three books on new and rediscovered animals (© Dr Karl Shuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)

December 21, 2022

A SOUTH AMERICAN LEMUR AND A MODERN-DAY GROUND SLOTH? A PAIR OF PUZZLING ANIMAL PORTRAITS IN AN 18TH-CENTURY ARTISTIC MASTERPIECE

Madagascan black-and-white ruffed lemur (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Madagascan black-and-white ruffed lemur (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Down through the years, I've investigated a number of mystifying animal artworks, depicting species before they were officially discovered by science, or in locations far removed from where they are officially known to exist. Examples from the former category include various anachronistic representations of kangaroos (one of which I documented in my book The Unexplained, 1996); and the following case is a prime example (but one hitherto undocumented by me) from the latter category. So I am greatly indebted to correspondent Cristian Nahuel Rojas Mendoza for very kindly bringing it to my attention, on 17 December 2022, and which I lost no time in subsequently investigating – thanks, Cristian!

The work of art containing the portrayed out-of-place animal in question is a magnificent yet surprisingly little-known pictorial encyclopaedia in the form of a spectacular mural, entitled Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geografica del Reyno del Peru ('Painting of the Natural, Civil and Geographical History of the Kingdom of Peru'), or QHNCGRP for convenience hereafter in this present ShukerNature blog article of mine. Consisting of numerous miniature oil paintings and accompanying text on a wood panel, it measures a very impressive 128 x 45.25 inches (325 x 115 cm).

QHNCGRP was authored by Basque-born but (for three decades) Peru-based scholar José Ignacio Lequanda, who commissioned French artist Louis Thiébaut to produce the paintings illustrating it, and it was completed in Madrid in 1799 (click herefor an extensive article by Daniela Bleichmar documenting its history and contents).

Today, this unique creation is held and displayed at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid, Spain (constituting Spain's national museum of natural history), which has produced an exquisite, lavishly-illustrated website devoted specifically to it (click here to visit the website). I strongly recommend that you access this site while reading my article here, in order to appreciate fully the nature, context, content, and visual beauty of this truly extraordinary, combined work of art and scholarship, and in particular the two items from it under consideration here.

View of QHNCGRP in its entirety

–

click to enlarge for viewing purposes (© Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

View of QHNCGRP in its entirety

–

click to enlarge for viewing purposes (© Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Containing a grand total of 214 individual images, QHNCGRP presents a picture-driven history of the peoples, animals, and plants of Peru (or, in a few cases, Peru's South American environs). At its centre there is an annotated map of the country, depicting, describing, and delineating its various administrative divisions in different colours, as well as a picture of the mine of Hualgayoc or Chota, emphasizing the significance of mining to Peru at that time.

Constituting the outermost border or frame of QHNCGRP is a series of 88 miniature paintings, each depicting a different Peruvian bird and plant, plus four corner miniatures portraying Peruvian insects. And running horizontally directly below the uppermost edge of this ornithologically-themed border is a row of 32 miniatures portraying various human forms, including indigenous peoples and Western couples in various costumes.

Below these, and forming a second, internal frame, is a series of numerous compartments containing Lequanda's tiny but voluminous handwritten text (he also added a descriptive label beneath each animal miniature, and considerable text around the mine picture). Within this second frame are not only four large pictures depicting Peruvian animals but also (split into a left-hand block and a right-hand block of 30 each) a series of 60 miniature paintings, again depicting Peruvian animals. Well, 59 of them are…

As for the 60th: This is the creature portrayed in the miniature present at the right-hand end of the top row in the right-hand block of 30 animal pictures. It seems to have been painted with especial precision by Thiébaut in comparison with certain other of the animals portrayed by him in QHNCGRP, and was labeled here by Lequandra as a mountain-abounding 'Dominican monkey'.

The so-called 'Dominican monkey' miniature painting in close-up; and also shown (arrowed, top row) in situ within QHNCGRP

–

click to enlarge for viewing purposes

(public domain)

The so-called 'Dominican monkey' miniature painting in close-up; and also shown (arrowed, top row) in situ within QHNCGRP

–

click to enlarge for viewing purposes

(public domain)

In reality, however, as anyone even remotely versed in mammalian identification will readily confirm, this particular creature, its distinctive monochrome form being both instantly recognizable and wholly unmistakable, is actually a black-and-white ruffed lemur Varecia variegata, the species depicted in the photograph opening this ShukerNature article, and which is of course endemic to Madagascar! No lemurs of any kind occur anywhere in the New World.

So why is there a portrait of a Madagascan lemur in QHNCGRP, which is exclusively devoted to Neotropical natural history and culture?

The most reasonable explanation, indicated by Lequanda's accompanying text (and also noted by Bleichmar in her afore-mentioned article), stems from his great familiarity with the contents of Madrid's prestigious – and exceedingly prodigious – Royal Natural History Cabinet, which was founded in 1771 and opened to the public in 1776. For within its collection of zoological specimens was none other than a preserved example of the black-and-white ruffed lemur. As this collection would have been consulted by both Lequanda and Thiébaut during their joint preparation of QHNCGRP, one or both of them presumably assumed mistakenly that the lemur specimen was of South American origin, and thus its striking appearance was incorporated accordingly within the QHNCGRP. But that is not all.

There is a second animal miniature in QHNCGRP that also attracted my interest and attention when perusing the latter's artworks. If you want to seek out this picture in QHNCGRP, it's the second miniature along in the fourth row within the right-hand block of 30 animal miniatures. Or, to make things simpler, here it is:

The so-called 'Nonga' miniature painting in close-up; and also shown (arrowed, fourth row) in situ within QHNCGRP

–

click to enlarge for viewing purposes

(public domain)

The so-called 'Nonga' miniature painting in close-up; and also shown (arrowed, fourth row) in situ within QHNCGRP

–

click to enlarge for viewing purposes

(public domain)

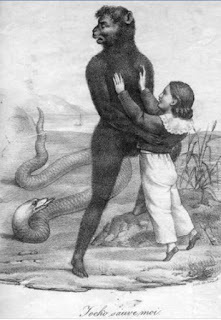

According to Lequanda's accompanying text, the Nonga lives on the banks of the River Huallaga (whose source is in central Peru), and is a nocturnal creature greatly feared by the Indians, but which according to Lequansda seems to be a forest spirit rather than a real entity.

When I first looked at this creature, I thought straight away that it resembled a tree sloth in basic outward morphology. But tree sloths do not stand upright, nor are they greatly feared by natives, and far from being forest spirits they are very familiar members of the corporeal animal community throughout the Neotropical zone.

However, their extinct relatives the ground sloths did stand upright, might well be greatly feared by natives due to their very large size and huge claws, especially if they happened to be ill-tempered creatures, readily becoming aggressive if threatened, and, like many other belligerent beasts, may indeed be deemed by their human neighbours to be supernatural spirits as much as flesh-and-blood animals.

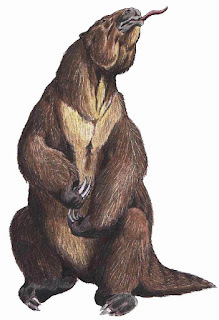

So could this miniature by Thiébaut be a depiction of a modern-day, scientifically-undiscovered ground sloth? Certain South American cryptids, such as the ellengassen and (especially) the mapinguary, are already looked upon by some cryptozoologists and zoologists as potentially constituting surviving ground sloths.

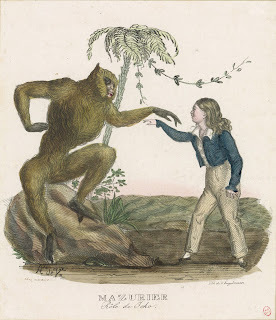

Image of a ground sloth (public domain)

Image of a ground sloth (public domain)

Unfortunately for such romantic speculation, however, the depicted creature's tiny tail is much more comparable with that of a three-toed tree sloth (two-toed tree sloths are tailless) than with the fairly long and very sturdy caudal appendage exhibited by bona fide ground sloths, which they used for support and balance when squatting upright.

Consequently, my personal opinion is that this mystifying miniature painting was based upon a preserved three-toed tree sloth, but whose normal behaviour of hanging upside-down from tree branches was not known to Liébaut, so he portrayed it incorrectly as a bipedal beast instead, thereby inadvertently recalling its officially extinct terrestrial relatives.

My sincere thanks once again to Cristian Nahuel Rojas Mendoza for alerting me to QHNCGRPand, in so doing, adding another very intriguing zoogeographical anomaly from the art world to my archive of such examples.

For an extremely extensive account of putative living ground sloths, be sure to check out my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors.

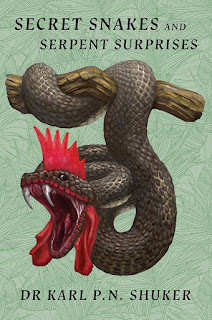

FIRE SERPENTS, SAND SERPENTS, AND A SERPENT KING ��� A TRIO OF CRYPTO-CREATURE FEATURES UNCOILING ON-SCREEN!

Publicity posters for Fire Serpent, Sand Serpents, and Basilisk: TheSerpent King (�� John Terlesky/CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/OutrageProductions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate HomeEntertainment // Jeff Renfroe/Media Pro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/SyFy/RHIEntertainment // Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures ��� allthree posters reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Publicity posters for Fire Serpent, Sand Serpents, and Basilisk: TheSerpent King (�� John Terlesky/CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/OutrageProductions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate HomeEntertainment // Jeff Renfroe/Media Pro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/SyFy/RHIEntertainment // Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures ��� allthree posters reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only) It's always a pleasure to watch creaturefeatures in which the monsters in question are far removed from the usual cinematicstereotypes (e.g. ferocious man-beasts, werewolves, sea monsters, gargantuaninsects, prehistoric survivors), and the three examples appearing in the trioof monster movies reviewed by me here, courtesy originally of ShukerNature's sister blog, Shuker In MovieLand, are definitely out of the ordinary, that's for sure!They display a vermiform similarity, but their respective origins could not bemore dissimilar ��� cast down to Earth from the scorching surface of the sun, rudelyawoken from deep subterranean desert dreaming, and resurrected from a verylengthy petrified past.

A second publicity poster for Fire Serpent (��

John Terlesky/

CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/OutrageProductions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate HomeEntertainment ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

A second publicity poster for Fire Serpent (��

John Terlesky/

CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/OutrageProductions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate HomeEntertainment ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

FIRE SERPENT

My movie watch on 25 August 2022 was ahighly original sci fi/monster movie entitled Fire Serpent.

Directed by John Terlesky, created bycelebrated Star Trek actor WilliamShatner, and originally screened in 2007 by the Sci-Fi Channel, Fire Serpent has as its central conceptthe notion that every so often throughout history, one of these eponymousfire-embodied serpentine entities is shot forth via solar flares from the sun'sscorching surface down to Earth, where it commits all manner of mayhem,inducing large-scale blazes, forest fires, etc in its search for fuel torevitalise it.

In so doing, this ophidian flame-spreaderwill even take over humans in its bid to destroy anyone who stands in its pathbefore incinerating them internally yet without leaving a mark on themexternally. Needless to say, spontaneous human combustion instantly comes tomind here, but sadly ��� and strangely ��� this extraordinary yet still-unexplainedfiery phenomenon is neither mentioned by name nor incorporated in any waywithin the movie.

The existence of fire serpents is knownto the US government but is kept a closely-guarded secret until maverickfirefighter Dutch Fallon (played by Randolph Mantooth), whose girlfriend waskilled by one of these flying furnaces, decides to devise a means of destroyingthem. This does not go down well with one mysterious government agent inparticular, however, a religious fanatic and covert arsonist named Cooke(Robert Beltran) who believes that they are fiery angels sent by God to cleansethe world by fire in order to renew it.

Can Dutch and a couple of semi-believingassociates put a stop both to the fire serpents and to the fire-preaching maniacCooke who seeks to harness them in his mad bid for catastrophic globalconflagration?

The CGI fire serpents are well executed,and, as I say, this movie's theme is unusual enough to keep even a hardenedseen-it-all creature feature fan like me interested and entertained.

If you'd care to gaze from theflame-retardant safety of your sofa at the coruscating creatures featured inthis incandescent movie, be sure to click hereto watch an official Fire Serpenttrailer on YouTube that won't leave you feeling hot under the collar!

Close-up of a giant sand serpent inSand Serpents (�� Jeff Renfroe/MediaPro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/Syfy/RHI Entertainment ��� reproduced here on astrictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Close-up of a giant sand serpent inSand Serpents (�� Jeff Renfroe/MediaPro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/Syfy/RHI Entertainment ��� reproduced here on astrictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

SAND SERPENTS

On 29 June2022, my movie watch was the crypto-themed Canadian film Sand Serpents.

Directedby Jeff Renfroe, and released on the Syfy Channel in 2009, Sand Serpents is definitely one of the better entries in thelong-running made-for-TV 'Maneater' series of sci fi/horror creature featuresproduced by RHI Entertainment for Syfy and released from 2007 onwards.

Think Tremors, but set in Afghanistan(although filmed in Romania), SandSerpents centres upon a small US special forces military squad led by Lieutenant RichardStanley (played by Jason Gedrick) and seeking toelude the Taliban, but also facing an even deadlier and far more unexpected foe��� 60-ft-long predatory worms disturbed from their subterranean realm by amassive explosion and now hunting down and devouring or destroying anythingthat betrays its presence to them via loud sounds or other vibrations. Not evenhelicopters flying overhead are safe from these voracious vermiforms that rearup into the sky and swallow the whirlybirds in a single gulp. Gulp!

Thesquad's only hope is to make its way through a series of underground tunnels toa location where yet another helicopter will attempt to rescue them, but theworms seem intent upon picking them off, one by one... Make sure that you watchthis movie right to the very end, because the closing scene contains a very dramaticand unexpected albeit somewhat unnecessary twist.

For alow-budget movie, its CGI mega-worms are excellent, with Sand Serpents a worthy homage to the Tremors franchise, and an equally worthy addition to mycrypto-cinema collection.

Moreover, ifwhat I've read in various reviews of it elsewhere is true, this movie'sportrayal of the US military in action in Afghanistan is a decent, relatively accuraterepresentation (though apparently there are various authenticity issuesconcerning the soldiers' outfits and insignia ��� as someone not well-informed onmilitary matters, however, I couldn't say).

For a spectaculartaster of what to expect down deep in the desert where the giant sand serpentsdwell, be sure to click hereto view a trailer of sand serpent excerpts from this movie on YouTube.

A French publicity poster for Basilisk: The Serpent King (�� StephenFurst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures ��� reproduced here on a strictlynon-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A French publicity poster for Basilisk: The Serpent King (�� StephenFurst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures ��� reproduced here on a strictlynon-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

BASILISK: THE SERPENT KING

Viewed on the UK's Horror [now renamedLegend] TV Channel, my movie watch for 18 June 2022 was the creature feature Basilisk: The Serpent King.

Directed by Stephen Furst, filmed inBulgaria, and released in 2006 on the Sci Fi Channel, Basilisk: The Serpent King opens with a modern-day discovery in theMiddle East of what appear on first sight to be a series of stone statues ofsoldiers dating back two millennia. These are brought back to the States by thearchaeological team that has discovered them, led by DrHarrison 'Harry' McColl (played by Jeremy London), together with their mostextraordinary find there ��� namely, what again seems to be a stone statue, butthis time of an enormous serpentine dragon, plus a very ornateserpent-ornamented sceptre containing a beautiful precious stone.

However, it's not long before the terrifyingtruth emerges ��� these 'statues' are actually petrified humans. Moreover, whenthe giant serpentine dragon 'statue' is put on display in the Colorado universitymuseum sponsoring Harry's archaeological dig, and sensationally comes to life duringa major reception there for the museum's wealthy patrons via an unexpectedphoto-reaction involving the sceptre and a solar eclipse, it turns out to be abasilisk, which spits forth a deadly white liquid that when activated by itsincandescent gaze promptly turns to stone a fair few of its awe-struckaudience. Not only that, it's pregnant! (Not so much a Serpent King as a SerpentQueen, therefore, or are there aspects of basilisk reproduction that I have yetto learn about??)

Anyway, much mayhem results, especially whenthe basilisk lays waste to a multi-story indoor shopping centre (whose property& contents insurance is unlikely to cover wholesale destruction caused by amythical mega-monster!), and the U.S. army is brought into play in a desperate bidto nullify this Medusa-mouthed Middle Eastern mall-wrecker.

Meanwhile, Harry and friends (one ofwhom, Carlton, is played by director Furst) no less desperately attempt to regainpossession of the sceptre that has been stolen by a wily and wealthy albeitdecidedly wacky villainess named Hannah (Yancy Butler). She plans to use it touncover a priceless cache of treasure, uncaring that it also happens to be theonly object in existence that can counter the basilisk.

Notwithstanding its ostensibly incongruous,spindly little legs (even though some traditional basilisk depictions do indeedsupply it with limbs), the CGI basilisk is very acceptable, and whereas thereis an emphasis upon wisecracks and goofy characters, this monster movie still boastsits fair share of thrills along the way too. Basilisk: The Serpent King was a film hitherto unknown to me but onethat I certainly enjoyed, and also recorded in order to add it to the crypto-themedsection of my movie collection, as I have so far been unable to locate it onDVD.

Incidentally, for the benefit of zoomythologyzealots, I must point out two intrinsic discrepancies between this movie's basiliskand traditional ones. Firstly: although the basilisk is indeed referred to in classicallegends as the king of the serpents, it is usually represented as being quitesmall, certainly nothing remotely as sizeable as this film's gargantuanrepresentative. Secondly: and according once again to legends, should abasilisk direct its gaze or its venom upon anyone (or any other living thing),the latter is instantly killed, not turned to stone ��� that more specialised slayingability is instead reserved for the trio of gorgons in Greek mythology.

Nevertheless, here and here, to petrify you, but, happily, not in a gorgonesque manner, are a couple of Basilisk: The Serpent King clips onYouTube.

Aclose encounter of the basilisk variety in Basilisk:The Serpent King

(�� Stephen Furst/BUFO/CurmudgeonFilms/Sci Fi Pictures ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Usebasis for educational/review purposes only)

Aclose encounter of the basilisk variety in Basilisk:The Serpent King

(�� Stephen Furst/BUFO/CurmudgeonFilms/Sci Fi Pictures ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Usebasis for educational/review purposes only)

FIRE SERPENTS, SAND SERPENTS, AND A SERPENT KING – A TRIO OF CRYPTO-CREATURE FEATURES UNCOILING ON-SCREEN!

Publicity posters for Fire Serpent, Sand Serpents, and Basilisk: The Serpent King (© John Terlesky/CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/Outrage Productions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate Home Entertainment // Jeff Renfroe/Media Pro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/SyFy/RHI Entertainment // Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures – all three posters reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Publicity posters for Fire Serpent, Sand Serpents, and Basilisk: The Serpent King (© John Terlesky/CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/Outrage Productions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate Home Entertainment // Jeff Renfroe/Media Pro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/SyFy/RHI Entertainment // Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures – all three posters reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only) It's always a pleasure to watch creature features in which the monsters in question are far removed from the usual cinematic stereotypes (e.g. ferocious man-beasts, werewolves, sea monsters, gargantuan insects, prehistoric survivors), and the three examples appearing in the trio of monster movies reviewed by me here, courtesy originally of ShukerNature's sister blog, Shuker In MovieLand, are definitely out of the ordinary, that's for sure! They display a vermiform similarity, but their respective origins could not be more dissimilar – cast down to Earth from the scorching surface of the sun, rudely awoken from deep subterranean desert dreaming, and resurrected from a very lengthy petrified past.

A second publicity poster for Fire Serpent (©

John Terlesky/

CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/Outrage Productions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate Home Entertainment – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A second publicity poster for Fire Serpent (©

John Terlesky/

CineTel Films/Kandu Entertainment/Outrage Productions/Premiere Bobine/S.V. Scary Films/Sci-Fi Channel/Lionsgate Home Entertainment – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

FIRE SERPENT

My movie watch on 25 August 2022 was a highly original sci fi/monster movie entitled Fire Serpent.

Directed by John Terlesky, created by celebrated Star Trek actor William Shatner, and originally screened in 2007 by the Sci-Fi Channel, Fire Serpent has as its central concept the notion that every so often throughout history, one of these eponymous fire-embodied serpentine entities is shot forth via solar flares from the sun's scorching surface down to Earth, where it commits all manner of mayhem, inducing large-scale blazes, forest fires, etc in its search for fuel to revitalise it.

In so doing, this ophidian flame-spreader will even take over humans in its bid to destroy anyone who stands in its path before incinerating them internally yet without leaving a mark on them externally. Needless to say, spontaneous human combustion instantly comes to mind here, but sadly – and strangely – this extraordinary yet still-unexplained fiery phenomenon is neither mentioned by name nor incorporated in any way within the movie.

The existence of fire serpents is known to the US government but is kept a closely-guarded secret until maverick firefighter Dutch Fallon (played by Randolph Mantooth), whose girlfriend was killed by one of these flying furnaces, decides to devise a means of destroying them. This does not go down well with one mysterious government agent in particular, however, a religious fanatic and covert arsonist named Cooke (Robert Beltran) who believes that they are fiery angels sent by God to cleanse the world by fire in order to renew it.

Can Dutch and a couple of semi-believing associates put a stop both to the fire serpents and to the fire-preaching maniac Cooke who seeks to harness them in his mad bid for catastrophic global conflagration?

The CGI fire serpents are well executed, and, as I say, this movie's theme is unusual enough to keep even a hardened seen-it-all creature feature fan like me interested and entertained.

If you'd care to gaze from the flame-retardant safety of your sofa at the coruscating creatures featured in this incandescent movie, be sure to click hereto watch an official Fire Serpenttrailer on YouTube that won't leave you feeling hot under the collar!

Close-up of a giant sand serpent in Sand Serpents (© Jeff Renfroe/Media Pro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/Syfy/RHI Entertainment – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Close-up of a giant sand serpent in Sand Serpents (© Jeff Renfroe/Media Pro Pictures/Muse Entertainment/Syfy/RHI Entertainment – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

SAND SERPENTS

On 29 June 2022, my movie watch was the crypto-themed Canadian film Sand Serpents.

Directed by Jeff Renfroe, and released on the Syfy Channel in 2009, Sand Serpents is definitely one of the better entries in the long-running made-for-TV 'Maneater' series of sci fi/horror creature features produced by RHI Entertainment for Syfy and released from 2007 onwards.

Think Tremors, but set in Afghanistan (although filmed in Romania), Sand Serpents centres upon a small US special forces military squad led by Lieutenant Richard Stanley (played by Jason Gedrick) and seeking to elude the Taliban, but also facing an even deadlier and far more unexpected foe – 60-ft-long predatory worms disturbed from their subterranean realm by a massive explosion and now hunting down and devouring or destroying anything that betrays its presence to them via loud sounds or other vibrations. Not even helicopters flying overhead are safe from these voracious vermiforms that rear up into the sky and swallow the whirlybirds in a single gulp. Gulp!

The squad's only hope is to make its way through a series of underground tunnels to a location where yet another helicopter will attempt to rescue them, but the worms seem intent upon picking them off, one by one... Make sure that you watch this movie right to the very end, because the closing scene contains a very dramatic and unexpected albeit somewhat unnecessary twist.

For a low-budget movie, its CGI mega-worms are excellent, with Sand Serpents a worthy homage to the Tremors franchise, and an equally worthy addition to my crypto-cinema collection.

Moreover, if what I've read in various reviews of it elsewhere is true, this movie's portrayal of the US military in action in Afghanistan is a decent, relatively accurate representation (though apparently there are various authenticity issues concerning the soldiers' outfits and insignia – as someone not well-informed on military matters, however, I couldn't say).

For a spectacular taster of what to expect down deep in the desert where the giant sand serpents dwell, be sure to click hereto view a trailer of sand serpent excerpts from this movie on YouTube.

A French publicity poster for Basilisk: The Serpent King (© Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A French publicity poster for Basilisk: The Serpent King (© Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

BASILISK: THE SERPENT KING

Viewed on the UK's Horror [now renamed Legend] TV Channel, my movie watch for 18 June 2022 was the creature feature Basilisk: The Serpent King.

Directed by Stephen Furst, filmed in Bulgaria, and released in 2006 on the Sci Fi Channel, Basilisk: The Serpent King opens with a modern-day discovery in the Middle East of what appear on first sight to be a series of stone statues of soldiers dating back two millennia. These are brought back to the States by the archaeological team that has discovered them, led by Dr Harrison 'Harry' McColl (played by Jeremy London), together with their most extraordinary find there – namely, what again seems to be a stone statue, but this time of an enormous serpentine dragon, plus a very ornate serpent-ornamented sceptre containing a beautiful precious stone.

However, it's not long before the terrifying truth emerges – these 'statues' are actually petrified humans. Moreover, when the giant serpentine dragon 'statue' is put on display in the Colorado university museum sponsoring Harry's archaeological dig, and sensationally comes to life during a major reception there for the museum's wealthy patrons via an unexpected photo-reaction involving the sceptre and a solar eclipse, it turns out to be a basilisk, which spits forth a deadly white liquid that when activated by its incandescent gaze promptly turns to stone a fair few of its awe-struck audience. Not only that, it's pregnant! (Not so much a Serpent King as a Serpent Queen, therefore, or are there aspects of basilisk reproduction that I have yet to learn about??)

Anyway, much mayhem results, especially when the basilisk lays waste to a multi-story indoor shopping centre (whose property & contents insurance is unlikely to cover wholesale destruction caused by a mythical mega-monster!), and the U.S. army is brought into play in a desperate bid to nullify this Medusa-mouthed Middle Eastern mall-wrecker.

Meanwhile, Harry and friends (one of whom, Carlton, is played by director Furst) no less desperately attempt to regain possession of the sceptre that has been stolen by a wily and wealthy albeit decidedly wacky villainess named Hannah (Yancy Butler). She plans to use it to uncover a priceless cache of treasure, uncaring that it also happens to be the only object in existence that can counter the basilisk.

Notwithstanding its ostensibly incongruous, spindly little legs (even though some traditional basilisk depictions do indeed supply it with limbs), the CGI basilisk is very acceptable, and whereas there is an emphasis upon wisecracks and goofy characters, this monster movie still boasts its fair share of thrills along the way too. Basilisk: The Serpent King was a film hitherto unknown to me but one that I certainly enjoyed, and also recorded in order to add it to the crypto-themed section of my movie collection, as I have so far been unable to locate it on DVD.

Incidentally, for the benefit of zoomythology zealots, I must point out two intrinsic discrepancies between this movie's basilisk and traditional ones. Firstly: although the basilisk is indeed referred to in classical legends as the king of the serpents, it is usually represented as being quite small, certainly nothing remotely as sizeable as this film's gargantuan representative. Secondly: and according once again to legends, should a basilisk direct its gaze or its venom upon anyone (or any other living thing), the latter is instantly killed, not turned to stone – that more specialised slaying ability is instead reserved for the trio of gorgons in Greek mythology.

Nevertheless, here and here, to petrify you, but, happily, not in a gorgonesque manner, are a couple of Basilisk: The Serpent King clips on YouTube.

A close encounter of the basilisk variety in Basilisk: The Serpent King

(© Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A close encounter of the basilisk variety in Basilisk: The Serpent King

(© Stephen Furst/BUFO/Curmudgeon Films/Sci Fi Pictures – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

December 18, 2022

AN EXCLUSIVE NEW PORTRAIT OF THE IRISH ELK ��� A SHUKERNATURE PICTURE OF THE DAY

Adramatic, previously-unpublished portrait of an adult male Irish elk aka thegiant deer Megaloceros giganteus (��Wayne Patton)

Adramatic, previously-unpublished portrait of an adult male Irish elk aka thegiant deer Megaloceros giganteus (��Wayne Patton)They say that good things come in pairs,so after the very favourable response recently received by my firstShukerNature Picture of the Day posted by me for quite some time (click hereto access it), without further ado I am very happy to proffer a second one right now. Namely, the dramatic and exceedingly impressive but previously-unpublished portrait by American scholar/wildlife artistWayne Patton (kindly forwarded to me earlier this year upon his behalf by hisdaughter, Alison Fielding) of one of prehistory's most spectacular mammals ���the Irish elk, also known very aptly as the giant deer, and scientifically as Megaloceros giganteus.

Famed for the adult male's immenseantlers, this awe-inspiring species was traditionally believed to have become extinctthroughout its Eurasian distribution range during the Pleistocene epoch, i.e.prior to the onset of the Holocene, approximately 10,600 years ago. However, withinmy book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors(1995), I presented some intriguing evidence for its possible survival into theearly Holocene (including mention of a mysterious, still-unidentified Europeanbeast named the schelk or shelk that may allude to Holocene representatives of Megaloceros).

Moreover, some years later, as I duly updatedin a ShukerNature article (click here)as well as in my subsequent book Still In Search OfPrehistoric Survivors (2016),conclusive evidence for this species' Holocene survival in two widely separateEurasian localities ��� the Isle of Man off the British mainland, and western Siberiain far-eastern Russia ��� was indeed obtained.

Inspired by my writings as well as thoseof many others dealing with this magnificent species, together with all mannerof artistic representations of it, including cave paintings, and being anaccomplished artist himself, Wayne decided to prepare his own entirely originalreconstruction of its likely appearance in life, and when it was complete hevery kindly offered me the opportunity to reproduce it exclusively onShukerNature, which I was only too happy to accept. And so, showcased above asa wonderful ShukerNature Picture of the Day, is Wayne's stunning adult male Megaloceros painting, together with his verbatimaccount below of how he came to prepare it, his influences, and personalthoughts and ideas concerning Megaloceros,presented once again with his kind permission.

[Incidentally, please note that Wayne isusing the term 'shelk' in his account merely as a common name for Megaloceros, rather than claiming adirect link between the latter deer and the mysterious still-unidentified beastof that name.]

Oneof Charles R. Knight's classic Irish elk paintings (public domain)

Oneof Charles R. Knight's classic Irish elk paintings (public domain)

My name is Wayne Patton, I am a botanistand soil scientist by training and experience. I worked a career for the USForest Service. I also worked in Mexico, Canada, and collaborated with groupsfrom Romania, and Israel. I am a big game hunter and I took game with ancientsystems like the bow and arrow and atlatl darts. I also tanned my own hideand made all manner of leather goods like saddle, tack, etc��� Art has been ahobby for as long as I can remember. Now I am too old to hunt, so I spenda lot of time painting and selling my work through several galleries. I gotvery interested in the Megalocerosgiganteus (shelk) through both my hunting and art experiences. I decided topaint a bull shelk as exampled above, starting with photos of mounted skeletonin museums in Ireland, Germany, and Scotland. There are even a couple mountedskeletons in the US that were obtained from Ireland. I fleshed out the bonesbased on my art experience as well as butchering big game animals like theAmerican elk as well as mule deer, goats, sheep, and some African animals likethe kudu. This part was easy, however, virtually all paintings of shelks byCharles R. Knight, who did early work for the Chicago Museum of NaturalHistory, as well as the paintings available on the internet, are sourced fromthe zoo, mostly, red deer and American elk. The artists painted these fatanimals that are standing around at half-mast from eating the wrong diet andbeing trapped, and then showing them with the giant horns of the giant shelk.Perhaps the best artwork is by the current great Dutch painter Rien Poortvliet [but] he copied the colors of the reddeer and missed key anatomical features like the Adams apple and shoulder humpof the real shelk. What about the color? All paintings seem to be copies of thered deer and American or Mongolian elk ��� is this correct?

I thought not, so I did a bunch ofresearch to find out if any information exists and I stumbled on to a fabulousbook called The Nature of Paleolithic Artby Dr R. Dale Guthrie, who was a professor at the University ofAlaska. He visited caves in France, Northern Spain and Italy, as well asmuseums containing engravings of animals on rocks, bones, and ivory from sitesin Europe. This formed a basis for his reconstruction of the bull and cowshelks. He also did a lot of work comparing Pleistocene cave art with animalsthat survived the Pleistocene extinctions like the Chamois, the Reindeer andthe Muskox and found this art to be very accurate and can be relied upon tohelp make decisions about color and animal appearance. The early people livedwith the animals and were keen observers and used their knowledge to hunt them,maybe hastened extinction in some cases. So, I used my firsthand knowledge ofusing skeletal remains to flesh out realistic animal anatomy, and I used mostof Dr R. Dale Guthrie���s conclusions from his experience looking at Pleistoceneart to get the best color information. My try at a painting of the Bull Shelkis enclosed.

Give me feedback of what you all think!

Also, use Amazon on the internet totrack down copies of the book I used for reference (The Nature of PaleolithicArt).

Also, have a look at RienPoortvliet in his book A Journey to TheIce Age (mammoths and other animals of the wild).

Now, back to some ideas of why manyshelk remains and those of perhaps of red deer or European elk (American Moose)have holes knocked in the top of their skulls. These animals were herded in tomarl pits and peat bogs where they became mired and trapped after which earlypeople, especially in Ireland, went out and killed them where they were. Thenthey butchered out the best cuts of meat including the heart, liver, andtongues. Along with the brains, all of which were considered delicacies as Ihave on occasion. Use the 'Meat Eater' series on Netflix as a reference. Themain use for brains, however, was not eating even though they are good! Theprimary reason for use is stabilizing and tanning leather, as I have donealso. Leather has been used since the Pleistocene to make all kinds ofclothing, gear and weapons. Use of brains or urine can be a smelly operation.

Life-sized statueof an adult male Megaloceros on displayat Crystal Palace, London, originally created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkinsduring the 1850s (�� Dr Karl Shuker)

Life-sized statueof an adult male Megaloceros on displayat Crystal Palace, London, originally created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkinsduring the 1850s (�� Dr Karl Shuker)

Wayne has raised some very interestingpoints here. In particdular, it is certainly true that observing cave paintings can offer variousvisual clues to the physical appearance of prehistoric beasts that cannot beprocured from fossils alone. Perhaps the most famous example of this is theapparent presence of striped markings on the body of the cave lion, as depictedin cave paintings of this extinct felid. So it is very significant that Wayne'sMegaloceros painting has incorporatedinformation encapsulated in these early firsthand eyewitness artworks.

Additionally, Wayne's informationconcerning the use of brains for tanning leather does indeed offer at least apartial explanation for the skull holes observed in Megaloceros remains that I documented in my first Prehistoric Survivors book andsubsequently reiterated in my second one as well as my ShukerNature article.And as it was entirely new to me, this information is very welcome.

In short, I am delighted to be able toshare with you Wayne's extremely striking, wholly original interpretation ofwhat the adult male Megaloceros mayhave looked like in life, and his input to what is known about the use by humanhunters of the brains extracted from the skulls of butchered deer that may well have applied to thisprehistoric species.

Once again, I thank Wayne most sincerely forpermitting me to share all of this here on ShukerNature, and also his daughter Alisonfor kindly making contact with me in order to bring Wayne's work to my attention.

For an extensive coverage of possible anddefinite examples of Megaloceros post-Pleistocenesurvival, be sure to check out my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors.

AN EXCLUSIVE NEW PORTRAIT OF THE IRISH ELK – A SHUKERNATURE PICTURE OF THE DAY

A dramatic, previously-unpublished portrait of an adult male Irish elk aka the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus (© Wayne Patton)

A dramatic, previously-unpublished portrait of an adult male Irish elk aka the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus (© Wayne Patton) They say that good things come in pairs, so after the very favourable response recently received by my first ShukerNature Picture of the Day posted by me for quite some time (click hereto access it), without further ado I am very happy to proffer a second one right now. Namely, the dramatic and exceedingly impressive but previously-unpublished portrait by American scholar/wildlife artist Wayne Patton (kindly forwarded to me earlier this year upon his behalf by his daughter, Alison Fielding) of one of prehistory's most spectacular mammals – the Irish elk, also known very aptly as the giant deer, and scientifically as Megaloceros giganteus.

Famed for the adult male's immense antlers, this awe-inspiring species was traditionally believed to have become extinct throughout its Eurasian distribution range during the Pleistocene epoch, i.e. prior to the onset of the Holocene, approximately 10,600 years ago. However, within my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors(1995), I presented some intriguing evidence for its possible survival into the early Holocene (including mention of a mysterious, still-unidentified European beast named the schelk or shelk that may allude to Holocene representatives of Megaloceros).

Moreover, some years later, as I duly updated in a ShukerNature article (click here) as well as in my subsequent book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors (2016), conclusive evidence for this species' Holocene survival in two widely separate Eurasian localities – the Isle of Man off the British mainland, and western Siberia in far-eastern Russia – was indeed obtained.

Inspired by my writings as well as those of many others dealing with this magnificent species, together with all manner of artistic representations of it, including cave paintings, and being an accomplished artist himself, Wayne decided to prepare his own entirely original reconstruction of its likely appearance in life, and when it was complete he very kindly offered me the opportunity to reproduce it exclusively on ShukerNature, which I was only too happy to accept. And so, showcased above as a wonderful ShukerNature Picture of the Day, is Wayne's stunning adult male Megaloceros painting, together with his verbatim account below of how he came to prepare it, his influences, and personal thoughts and ideas concerning Megaloceros, presented once again with his kind permission.

[Incidentally, please note that Wayne is using the term 'shelk' in his account merely as a common name for Megaloceros, rather than claiming a direct link between the latter deer and the mysterious still-unidentified beast of that name.]

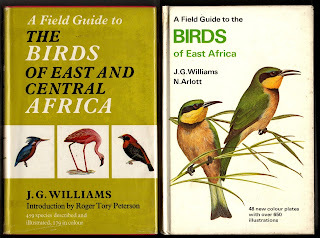

One of Charles R. Knight's classic Irish elk paintings (public domain)

One of Charles R. Knight's classic Irish elk paintings (public domain)

My name is Wayne Patton, I am a botanist and soil scientist by training and experience. I worked a career for the US Forest Service. I also worked in Mexico, Canada, and collaborated with groups from Romania, and Israel. I am a big game hunter and I took game with ancient systems like the bow and arrow and atlatl darts. I also tanned my own hide and made all manner of leather goods like saddle, tack, etc… Art has been a hobby for as long as I can remember. Now I am too old to hunt, so I spend a lot of time painting and selling my work through several galleries. I got very interested in the Megaloceros giganteus (shelk) through both my hunting and art experiences. I decided to paint a bull shelk as exampled above, starting with photos of mounted skeleton in museums in Ireland, Germany, and Scotland. There are even a couple mounted skeletons in the US that were obtained from Ireland. I fleshed out the bones based on my art experience as well as butchering big game animals like the American elk as well as mule deer, goats, sheep, and some African animals like the kudu. This part was easy, however, virtually all paintings of shelks by Charles R. Knight, who did early work for the Chicago Museum of Natural History, as well as the paintings available on the internet, are sourced from the zoo, mostly, red deer and American elk. The artists painted these fat animals that are standing around at half-mast from eating the wrong diet and being trapped, and then showing them with the giant horns of the giant shelk. Perhaps the best artwork is by the current great Dutch painter Rien Poortvliet [but] he copied the colors of the red deer and missed key anatomical features like the Adams apple and shoulder hump of the real shelk. What about the color? All paintings seem to be copies of the red deer and American or Mongolian elk – is this correct?

I thought not, so I did a bunch of research to find out if any information exists and I stumbled on to a fabulous book called The Nature of Paleolithic Artby Dr R. Dale Guthrie, who was a professor at the University of Alaska. He visited caves in France, Northern Spain and Italy, as well as museums containing engravings of animals on rocks, bones, and ivory from sites in Europe. This formed a basis for his reconstruction of the bull and cow shelks. He also did a lot of work comparing Pleistocene cave art with animals that survived the Pleistocene extinctions like the Chamois, the Reindeer and the Muskox and found this art to be very accurate and can be relied upon to help make decisions about color and animal appearance. The early people lived with the animals and were keen observers and used their knowledge to hunt them, maybe hastened extinction in some cases. So, I used my firsthand knowledge of using skeletal remains to flesh out realistic animal anatomy, and I used most of Dr R. Dale Guthrie’s conclusions from his experience looking at Pleistocene art to get the best color information. My try at a painting of the Bull Shelk is enclosed.

Give me feedback of what you all think!

Also, use Amazon on the internet to track down copies of the book I used for reference (The Nature of Paleolithic Art).

Also, have a look at Rien Poortvliet in his book A Journey to The Ice Age (mammoths and other animals of the wild).