Karl Shuker's Blog, page 21

September 9, 2018

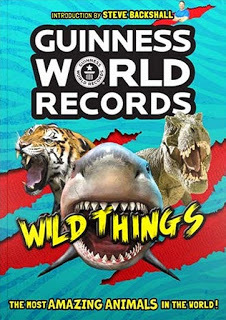

GOING WILD OVER GWR'S 'WILD THINGS' – THE ANIMAL WORLD'S MOST AMAZING RECORD-BREAKERS IN AN AWESOME NEW BOOK!

Guinness World Records: Wild Things

(© Guinness World Records/

GWR: Wild Things

)

Guinness World Records: Wild Things

(© Guinness World Records/

GWR: Wild Things

)In addition to the 26 books that I have written myself and seen published (#26 is due out shortly), I have also acted as a consultant and/or contributor to a further 18 – click here to access a (currently) complete listing of all of my books.

I am delighted to announce that the latest volume with which I have been involved in the dual capacity of consultant and contributor will be published next month but can already be pre-ordered on Amazon USA , Amazon UK , and elsewhere. It is entitled Guinness World Records: Wild Things , and here is a taster of what to expect:

Whether it's the biggest, the smallest, the fastest, the deadliest, or just the downright weirdest, Guinness World Records: Wild Things turns the spotlight on the best of the beasts! From gentle giants to killer bugs, powerful predators to cunning prey, and backyard wildlife to species on the brink, the animal kingdom is crawling with record-breakers.

Spread featuring an interview with Steve Backshall - click image to enlarge for reading purposes (© Guinness World Records/

GWR: Wild Things

)

Spread featuring an interview with Steve Backshall - click image to enlarge for reading purposes (© Guinness World Records/

GWR: Wild Things

)Wild Things is your ultimate guide to nature's super-star animals. There's a special chapter all about prehistoric record-breakers too. Unearth which ancient animals ruled over the real Jurassic world, from the tallest dinosaur and the dino with the most powerful bite to the largest flying creature ever to soar Earth's skies with a wingspan the size of an F-16 jet!

You'll also hear from zoology experts and some of the biggest conservation stars including Sir David Attenborough, Dr Jane Goodall, the Irwin family, and Deadly 60's Steve Backshall (who supplies a foreword too). In exclusive interviews, they share their standout wildlife experiences, favourite record-breaking animals, plus top tips for anyone hoping to follow in their footsteps.

Ready to find out where the real wild things are and the records that they hold? Then it's time to unleash the wildest GWR book yet!

My profile in

GWR: Wild Things

's Introduction - click image to enlarge for reading purposes (© Guinness World Records/

GWR: Wild Things

)

My profile in

GWR: Wild Things

's Introduction - click image to enlarge for reading purposes (© Guinness World Records/

GWR: Wild Things

)Full details can be found on this book's dedicated page here on my official website, which also contains direct clickable links to its page on the US and UK Amazon sites.

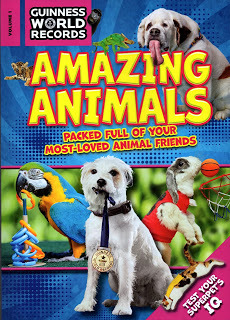

Also, don't forget to check out on my website its companion volume, GWR: Amazing Animals , published last year and once again featuring me as both its consultant and a contributor, which is packed throughout with fascinating record-breaking animal stars of the domesticated kind!

And click here to read about GWR: Amazing Animals on ShukerNature.

Guinness World Records: Amazing Animals

(© Guinness World Records/GWR: Amazing Animals)

Guinness World Records: Amazing Animals

(© Guinness World Records/GWR: Amazing Animals)

Published on September 09, 2018 18:11

September 5, 2018

THORNY-TAILED CATS AND A DOMESTIC MANTICORE

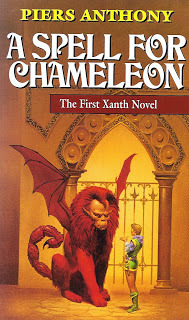

A winged manticore with a decidedly scorpionesque sting-tipped tail, depicted on the front cover of Piers Anthony's novel

A Spell For Chameleon

– one of my all-time favourite fantasy novels, and the first in Anthony's exceedingly popular, long-running Xanth series (© Del Rey Books – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational purposes only)

A winged manticore with a decidedly scorpionesque sting-tipped tail, depicted on the front cover of Piers Anthony's novel

A Spell For Chameleon

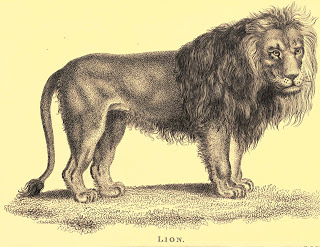

– one of my all-time favourite fantasy novels, and the first in Anthony's exceedingly popular, long-running Xanth series (© Del Rey Books – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational purposes only)Quite apart from its mane in the male, the lion Panthera leo is also set apart morphologically from all other cat species, at least officially, by virtue of a remarkable characteristic of its tail. Not only does it terminate in a hairy tassle-resembling tuft, but sometimes concealed within that tuft is a thorn-like spine that measures just a few millimetres long.

This unexpected structure's function, if indeed it has one, is unknown, as is that of the hairy tuft. Known variously as a thorn, spine, prickle, or caudal claw, it is not present when a lion cub is born, but develops when the cub is around five months old, and is readily visible two months later.

Lion showing the very distinctive tufted tail-tip that is peculiar to this species among felids (© Rufus46/Wikipedia –CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

Lion showing the very distinctive tufted tail-tip that is peculiar to this species among felids (© Rufus46/Wikipedia –CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)Click here (then scroll down to the end of this zoo news report) to view a close-up photograph of a leonine caudal claw, normally hidden by the hairy tuft at the tip of the lion's tail. This particular caudal claw is sported by an adult South African lion named Xerxes at Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington State, USA.

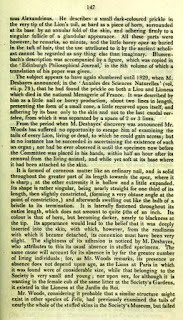

The most detailed coverage concerning caudal claws in lions that I have ever seen is an article originally published in Part 2 of the volume for 1832 of the now long-bygone journal Proceedings of the Committee of Science and Correspondence of the Zoological Society of London (it was subsequently republished in January 1833 within vol. 2, no. 7, of the third series of the London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science). Not only does this fascinating if nowadays exceedingly little-known report document the then-recent description of one such specimen by H. Woods to the Committee of Science and Correspondence of the Zoological Society of London, it also provides a detailed history of how such oddities were first brought to scientific attention and early thoughts as to what their function may be. In view of its scientific significance, therefore, I am reproducing this hitherto-obscure article in its entirety below:

WOODS, H., 'On the Claw of the Tip of the Tail of the Lion (Felis leo, L.)', Proc. Comm. Sci. and Corres. Zool. Soc. London, pt 2: 146-148 (1832) – please click pages to enlarge them for reading purposes (public domain)

WOODS, H., 'On the Claw of the Tip of the Tail of the Lion (Felis leo, L.)', Proc. Comm. Sci. and Corres. Zool. Soc. London, pt 2: 146-148 (1832) – please click pages to enlarge them for reading purposes (public domain)Although caudal claws are widely claimed to be sported only by the lion, I have encountered occasional reports of thorny-tailed tigers and leopards too (indeed, two such examples from leopards are briefly mentioned in the above-reproduced 1832 article). Although I have never seen an illustration of a caudal claw from either of these two latter species, the tail tip of such an animal must look very unusual – for as these species lack the lion's hairy tail tuft, the thorn of a thorny-tailed tiger or leopard would be visible, and may therefore resemble a scorpion-like sting!

In turn, such a bizarre image inevitably inspires speculation and theorising as to whether the sight of so oddly-equipped a big cat may have helped shape the legend of the fearsome if wholly fictitious manticore (click here to access my ShukerNature coverage of the manticore).

Close-up of the tufted tail-tip of a lion (public domain)

Close-up of the tufted tail-tip of a lion (public domain)If so, then what might surely be dubbed 'the littlest manticore' is a certain domestic cat documented as follows by a Mr R. Trimen within a letter published on 3 March 1908 in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London:

My cat (pale grey with ordinary narrow black stripes much broken up into short streaks and spots) presents the remarkable peculiarity of a long spur or claw-like horny excrescence at the very tip of its tail. This appendage is firmly seated quite at the extremity of the last vertebra; its base appears to be expanded, and is covered all round by an elevation of the skin. It projects posteriorly in the line of the tail, is rather slender, gradually tapering, almost straight for about two-thirds of its length, and thence moderately curved downward to its moderately acute tip. In length it is nearly 7 lines [1 line = 1/12thof 1 inch], and more than a third projects beyond the surrounding fur. The colour of this spine or spur is dull reddish-brown varied with dull ochry-yellowish, here and there crossed by some broken, thin, whitish lines.

The cat in question is a female, small, but rather thick in body; the limbs are all rather short and the feet small, but the tail is noticeably long and broad with long dense fur. I am informed by the donor that it was born at Witney, near Oxford, and is now between seven and eight months old. I have endeavoured, with the kind aid of the donor, to ascertain from the original possessor of the animal whether any kitten of the same litter, or the mother, or other known relation, exhibited the peculiar appendage or any traces of it; but without success.

I may add that I have found the cat unexpectedly sensitive to any handling of the caudal claw, however gentle; she first endeavours to jerk her tail away, then gives a mild vocal remonstrance, and if the handling is continued employs her paws to stop it.

Perhaps this cat's tail thorn or caudal claw was a deformed supernumerary caudal vertebra whose exposed site rendered it vulnerable to being caught against objects as the cat moved, causing the flesh surrounding it to be abnormally sensitive to pain.

Mystery Animals of

Ireland

by Gary Cunningham and Ronan Coghlan (© Gary Cunningham and Ronan Coghlan/CFZ Press)

Mystery Animals of

Ireland

by Gary Cunningham and Ronan Coghlan (© Gary Cunningham and Ronan Coghlan/CFZ Press)What may have been either a large domestic tabby or, more remarkably, a bona fide Irish wildcat (itself a feline cryptid of no little controversy that I documented comprehensively in my very first book, Mystery Cats of the World , 1989), was encountered during the 1940s or 1950s by the uncle and father of Pap Murphy in a shed at the end of the uncle's house on the Mullet, an island in northwest County Mayo, as documented by Gary Cunningham and Ronan Coghlan in their book Mystery Animals of Ireland (2010). Entangled in some fishing nets, the cat had growled at the men, who subsequently killed it. Examining its body, they were surprised to discover that it possessed a very sharp nail-like structure, possibly bony in composition, at the end of its tail.

It would be interesting to discover if any additional cases of 'domestic manticores' have been recorded.

Exquisite vintage engraving of a lion showing its characteristic tufted tail-tip – Plate 81 from

General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History

, by George Shaw, with plates engraved principally by Mr Heath; published in 1800 (public domain)

Exquisite vintage engraving of a lion showing its characteristic tufted tail-tip – Plate 81 from

General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History

, by George Shaw, with plates engraved principally by Mr Heath; published in 1800 (public domain)Finally: I have succeeded in tracking down a copy of the original article by German naturalist Prof. Johann F. Blumenbach that was extensively referred to in the above-reproduced 1832 article re H. Woods's description of the young Barbary lion's caudal claw. Blumenbach's article had been published in 1823 within the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal.

Accordingly, for the sake of completeness, I am reproducing it in its entirety below:

BLUMENBACH, Johann F., 'Art. VI. – Miscellaneous Notices in Natural History. 4. On the Prickle at the Extremity of the Tail of the Lion', Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, vol. 8, no. 16: 266-268 (1823) – please click pages to enlarge for reading purposes (public domain)

BLUMENBACH, Johann F., 'Art. VI. – Miscellaneous Notices in Natural History. 4. On the Prickle at the Extremity of the Tail of the Lion', Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, vol. 8, no. 16: 266-268 (1823) – please click pages to enlarge for reading purposes (public domain)This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted and expanded from my book Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery .

Published on September 05, 2018 16:50

August 11, 2018

REVIEWING 'THE MEG' – JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT IT WAS SAFE TO GO BACK IN THE CINEMA!

A publicity poster for The Meg (© Warner Bros. Pictures/Gravity Pictures/Flagship Entertainment/Apelles Entertainment/Di Bonaventura Pictures/maeday Productions – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A publicity poster for The Meg (© Warner Bros. Pictures/Gravity Pictures/Flagship Entertainment/Apelles Entertainment/Di Bonaventura Pictures/maeday Productions – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)I'm gonna need a bigger cinema! Yes indeed, I could well have been forgiven for thinking that, because the reason why I visited my own local picture house on 10 August was to see the newly-arrived cryptozoology-themed monster movie The Meg, which I've been awaiting with great anticipation for ages.

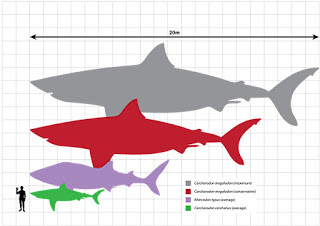

Size does matter: a visual comparison of the enormous dimensions of the megalodon (grey = maximum estimate, red = conservative estimate) with a whale shark (the world's largest known living species of fish; violet), the great white shark (green), and a human for scale (© Scarlet23/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Size does matter: a visual comparison of the enormous dimensions of the megalodon (grey = maximum estimate, red = conservative estimate) with a whale shark (the world's largest known living species of fish; violet), the great white shark (green), and a human for scale (© Scarlet23/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)Directed by Jon Turtelbaub, co-produced by Warner Bros. Pictures, and based upon the bestselling novel Meg by Facebook friend Steve Alten, its nominal star is Jason Statham, but its real stars are a couple of CGI megalodons, representing the giant prehistoric shark Carcharocles megalodon – the largest shark species ever recorded by science. Officially, it became extinct approximately 2.6 million years ago during the late Pliocene epoch, and is principally known physically only from fossilised teeth and vertebrae, but thanks to some intriguing eyewitness accounts on file of supposedly gargantuan sharks, some mystery beast investigators have speculated that it might still exist today. Be that as it may (or may not), this review of mine is of the film, not cryptozoology per se (click here to read my own thoughts concerning the exceedingly contentious prospect of megalodon survival as posted by me earlier on ShukerNature and excerpted from my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors ). So, back to the movie.

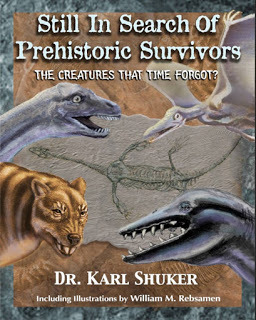

My book

Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors

, published in 2016 by Coachwhip (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

My book

Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors

, published in 2016 by Coachwhip (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)When the megalodon was first made known to science and formally named back in the 1840s, based upon its triangular and highly-serrated teeths' huge dimensions (up to 7.5 inches high - 'megalodon' translates as 'big tooth') an estimated total length for the entire shark of around 75-98 ftwas postulated, but in more recent times, following further researches, this estimate has been downsized to 'a mere' 43-55 ft(although to put that into perspective, this is still more than twice the length of the great white shark Carcharodon carcharias, the largest species of carnivorous shark KNOWN to exist today). However, The Meg is a monster movie, not a shark documentary, so the film makers have adhered to the flawed earlier but cinematically much more spectacular 75-ft dimension (think Jawswrit large - very large!!) - resulting in a truly mega megalodon, a prodigious prehistoric behemoth which if it had lived in an earlier geological era would have been a veritable Jurassic Shark (come on, you knew full well that I was never NOT going to work in that pun somewhere!).

My mother Mary Shuker holding one of my megalodon tooth specimens (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My mother Mary Shuker holding one of my megalodon tooth specimens (© Dr Karl Shuker)As this is a newly-released movie that many fellow cryptozoology fans will definitely be going to see, I'll avoid spoilers, but the scenario of how the megs are discovered is quite fascinating, and they have been digitally recreated on screen to stunning effect. Once their discovery has been made, however, the plot adheres by and large to the typical, generic monster movie storyline - a flawed but immensely brave hero sets out to confront said monster(s), interacts along the way with a villain and a naysayer, some wisecracking sidekicks, a cute extra-smart kid, and an initially aloof but ultimately adoring, sassy lady, and after a series of thrilling set pieces finally battles said monsters(s) in a climactic confrontation of epic proportions. But hey, you already guessed that without even needing to watch the film - and who goes to a monster movie to be blown away by the intricacy and intellectual, deeply philosophical nuances (or even the scientific authenticity) of its plot anyway?? What you go to see is the monster(s), and this movie definitely delivers on that score.

Cryptozoological artist William M. Rebsamen's portrayal of an imagined modern-day encounter between man and megalodon (© William M. Rebsamen)

Cryptozoological artist William M. Rebsamen's portrayal of an imagined modern-day encounter between man and megalodon (© William M. Rebsamen)I viewed it in 2-D, but I may well go back during its run to see the 3-D version too - I'm not normally a fan of 3-D movies, but there is no doubt that The Meg will do the format justice as it is exactly the type of film benefitted by it. Despite living over a hundred miles (maybe more) in any direction from the sea, an erstwhile friend of mine was seriously galeophobic (afraid of sharks), and I wouldn't recommend this film to anyone with a similar fear, but hardened monster fans will lap it up - it certainly engaged my attention and interest throughout. I can always tell how entertained my mind is by a film by noting how far through it I've viewed before looking at my watch to see what time it is and then calculating how much more of the film remains - with The Meg, I never looked at my watch once. One word of advice: don't bother, as I unfortunately did, (im)patiently sitting through the interminable credits at the end of the film in the expectation that there will be a teaser clip to some projected sequel inserted within or at the end of them - there isn't one. Oh, and just as a BTW: yes indeed, Pippin the Yorkshire terrier does survive his (very) close encounter with a megalodon (whoops, too late for a spoiler alert now).

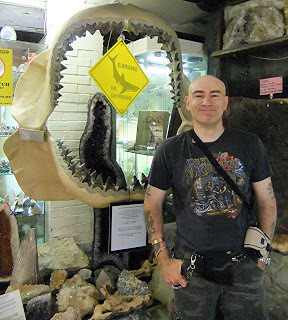

Standing in front of a life-sized reconstruction of a megalodon's open jaws (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Standing in front of a life-sized reconstruction of a megalodon's open jaws (© Dr Karl Shuker)I fully expect that some movie (and also possibly some palaeontological) purists will opine otherwise, but I LOVED The Meg, a worthy new addition to the ever-popular cinematic genre of giant beasts on the rampage, and which along with Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom and The Shape of Water (click here to read my ShukerNature review of the latter film) has definitely made my 2018 movie-going experience a truly monstrous one - but in the best possible way. Finally: to view on YouTube an extended trailer for The Meg, please click here .

The megalodon shark and the giant pliosaur Liopleurodon existed in entirely separate geological eras, so they would never have encountered each other in reality; but here in this vibrant artwork, illustrator Hodari Nundu depicts what such a clash of marine titans might have looked like had it indeed been possible (© Hodari Nundu)

The megalodon shark and the giant pliosaur Liopleurodon existed in entirely separate geological eras, so they would never have encountered each other in reality; but here in this vibrant artwork, illustrator Hodari Nundu depicts what such a clash of marine titans might have looked like had it indeed been possible (© Hodari Nundu) I wish to dedicate this ShukerNature article to my longstanding online friend and fellow cryptozoological enthusiast Robert Michaels, whose passing earlier this year I only learnt about on 10 August, just a few hours after returning home from watching The Meg at the cinema. How very much he would have enjoyed seeing this film, and how very sad I am that he will never do so. Godspeed, Bob, may you now know the answers to all of the countless cryptozoological questions concerning which we corresponded with such shared interest, enjoyment, and zeal over so many years. Please click here to read my tribute to Bob on ShukerNature.

Another publicity poster for The Meg (© Warner Bros. Pictures/Gravity Pictures/Flagship Entertainment/Apelles Entertainment/Di Bonaventura Pictures/maeday Productions – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Another publicity poster for The Meg (© Warner Bros. Pictures/Gravity Pictures/Flagship Entertainment/Apelles Entertainment/Di Bonaventura Pictures/maeday Productions – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Published on August 11, 2018 17:35

August 10, 2018

GOODBYE AND GODSPEED, BOB - REMEMBERING MY LONGSTANDING ONLINE FRIEND AND CRYPTOZOOLOGICAL COLLEAGUE ROBERT MICHAELS

The photograph of my senmurv jardiniere that Bob had long used as his profile picture on Facebook (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The photograph of my senmurv jardiniere that Bob had long used as his profile picture on Facebook (© Dr Karl Shuker)I was extremely sad to learn yesterday that my longstanding online friend and fellow cryptozoological enthusiast Robert Michaels had passed away, on 27 February. He was 85. Our friendship dated back almost to the very beginning of my own online presence, when I first signed up to the internet in 1997.

A qualified zoologist himself, graduating from Columbia University, Bob was passionately interested in all aspects of cryptozoology and was not just a very good friend to me but also an unwavering supporter of my work and a prolific communicator to the whole cryptozoological community via his numerous, continuing postings of fascinating news reports on my various cryptozoology-based FB groups - which is why, when Bob's postings stopped abruptly in February, with not a single one appearing anywhere since then, I became increasingly worried for his well-being and therefore posted a series of urgent requests on my timeline, on my groups, and on his own timeline for any information concerning his status. Thankfully, another good friend, Jane Cooper, who was also one of Bob's FB friends, duly investigated this on my behalf and on 10 August uncovered the sad news of his passing. Thank you so much, Jane, I greatly appreciate your kindness in doing this.

Just one of the countless encouraging, supportive comments that Bob so kindly posted about me and my work on Facebook - thanks Bob!

Just one of the countless encouraging, supportive comments that Bob so kindly posted about me and my work on Facebook - thanks Bob! Bob never posted an image of himself on his Facebook timeline, and since December 2014 he had used as his FB profile picture one of my photographs of my 19th-Century majolica jardiniere in the shape of a senmurv (aka cynogriffin). Consequently, from now on I shall always associate that photo, and indeed my senmurv jardiniere itself, with Bob, and I am therefore reproducing it here in tribute to him.

God bless you, Bob, for your friendship, and for your ever-present enthusiasm for cryptozoology and my own contributions to it - although we never met, and the great breadth of the Atlantic Ocean separated us in the real world, due to the modern miracle of the internet and social media you became a very close friend in the full sense of that word, and how very much I shall miss hearing from you and seeing your always-interesting, greatly-valued postings on FB. RIP Bob, you were one of the good guys, and I promise you that I will ensure through my writings that your name and your unstinting service to cryptozoology live on.

Bob's favourite cryptozoology-linked book, my

Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals

(© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

Bob's favourite cryptozoology-linked book, my

Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals

(© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

Published on August 10, 2018 20:23

July 29, 2018

THE AHOOL AND THE OLITIAU – GIANT MYSTERY BATS ON THE WING?

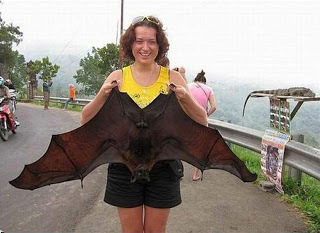

Photograph of hammer-headed bat currently doing the online rounds on social media (© owner presently unknown to me – reproduced here in a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational, review purposes only)

Photograph of hammer-headed bat currently doing the online rounds on social media (© owner presently unknown to me – reproduced here in a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational, review purposes only)During the past couple of days, several internet friends and colleagues have independently brought the above photograph to my attention, asking me whether the creature portrayed in it is real or photoshopped. I can confirm that it is indeed real – it is a specimen of tropical Africa's hammer-headed bat – but due to the optical illusion of forced perspective, i.e. caused by it being positioned much closer to the camera than is the person holding it, this very distinctive-looking bat appears much bigger than it really is.

Nevertheless, seeing this photograph reminds me of what may be some genuinely giant mystery bats, and regarding one of which the hammer-headed bat has indeed been considered as a possible explanation – so here they are.

Taxiderm specimen of a hammer-headed bat (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Taxiderm specimen of a hammer-headed bat (© Dr Karl Shuker)Native to New Guinea and the Bismark Archipelago, the world's largest known species of modern-day bat is the Bismark fruit bat Pteropus neohibernicus, which sports an extremely impressive wingspan of up to approximately 5.5 ft, and there are several other fruit bat species with sizeable spans too. Moreover, quoting from the third (most recent) edition of the late Gerald L. Wood's still-invaluable source of animal superlatives The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats:

According to Peterson (1964)* a huge example of P. neohibernicus from New Guinea preserved in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, has a head and body length of 455 mm 17.9 in and a span of 1.65 m 5 ft 5 in. He thinks that some unmeasured specimens may reach 183 m 6 ft, but this figure is unconfirmed.

*Peterson (1964) = Russell F. Peterson, Silently, By Night (McGraw-Hill: New York, 1964), an authoritative book on the natural history of bats, a copy of which I own.

However, the cryptozoological chronicles contain details concerning at least two types of giant mystery bats whose wingspan is claimed to be twice as big as the above!

Famous vintage photo of a fruit bat (species unnamed) with a very impressive wingspan (originally © Otto Webb, now public domain? – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial, Fair Use basis for educational, review purposes only)

Famous vintage photo of a fruit bat (species unnamed) with a very impressive wingspan (originally © Otto Webb, now public domain? – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial, Fair Use basis for educational, review purposes only)The secluded river valleys of western Java in Indonesia are reputedly home to one of these - an enormous but very elusive bat known to the local people as the ahool. It derives its name from the sound of its unmistakeable cry, which it is said to utter three times in succession while on the wing at night.

When questioned by interested Westerners, the locals provide consistent descriptions of the ahool. It has a monkey-like head and flattened humanoid face, a body as big as a one-year-old child's, and a massive 12-ft wingspan. It feeds principally upon large fishes that it snatches from underneath stones on river beds, but is occasionally encountered crouching on the forest floor, whereupon its feet are said to point backward. This last-mentioned feature may initially sound bizarre and implausible, but in reality it actually provides support for believing the remainder of their description, because as bat experts will readily testify, bats' feet do point backwards. Even when hanging upside-down from a branch, a bat wraps its feet around the rear portion of the branch, with its feet curling towards the observer, instead of away from him.

Does a giant bat, or bat-like cryptid, still awaiting scientific discovery explain reports of the ahool? (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Does a giant bat, or bat-like cryptid, still awaiting scientific discovery explain reports of the ahool? (© Dr Karl Shuker)One of the most interesting encounters with an ahool comes not from an eyewitness but rather an 'earwitness' (whose testimony was first documented by American cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson in a number of publications). The son of an eminent zoologist, naturalist Dr Ernst Bartels had spent much of his early life in Java, and was well-acquainted with the cries of all of the island's fauna. He was also familiar with the local Sundanese testimony concerning the ahool, but had remained sceptical – until one evening in 1927.

At around 11.30 pm, Dr Bartels had been lying awake in bed inside his thatched house near western Java's Tjidjenkol River, listening to the nocturnal insects' incessant orchestra of noises, when suddenly, from directly overhead, he heard a single loud, clear cry – "A-hool!". A few moments later, he heard it again, but further away now. Immediately, he jumped out of bed, grabbed his torch, and raced outside in the direction of the cry, whereupon he heard it again, for a third and final time, floating back to him from a considerable distance downstream. He stood there, totally transfixed, not because he didn't know what had made this unique triple cry, but rather because he did!

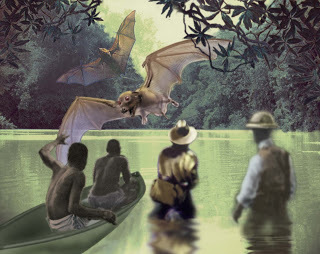

An olitiau encounter (© William M. Rebsamen)

An olitiau encounter (© William M. Rebsamen)A mystery bat of equally dramatic dimensions has also been encountered in Cameroon, West Africa, and by two very experienced scientific observers. While participating in the famous Percy Sladen Expedition of 1932, the afore-mentioned Ivan T. Sanderson and fellow animal-collector Gerald Russell had been wading down a stream in Cameroon's Assumbo Mountains one evening in search of tortoises to collect when abruptly a jet-black creature with enormous wings and a flattened monkey-like face flew out of the darkness and directly towards Sanderson, its lower jaw hanging down, revealing an abundance of large white teeth.

Sanderson instinctively ducked, then he and Russell fired a number of shots in the direction of this terrifying apparition, but it merely wheeled out of range and vanished back into the darkness, its wings cutting through the still air with a loud hissing sound. The two men agreed that its wingspan was at least 12 ft, and it seemed to have been jet-black in colour. When they told the local hunters back at their camp what had happened, the hunters were all terrified – so much so that after informing the naturalists that their would-be attacker was known as the olitiau, they all fled from the camp!

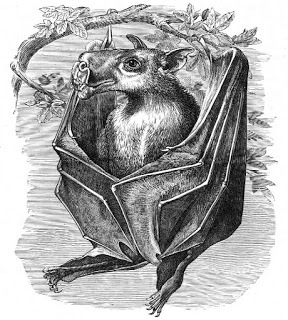

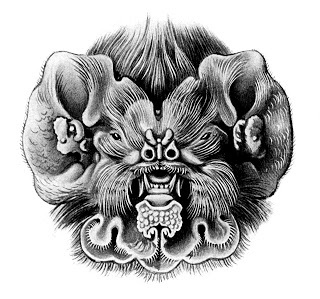

Exquisite 19th-Century engraving of the hammer-headed bat (public domain)

Exquisite 19th-Century engraving of the hammer-headed bat (public domain)Sceptics later sought to identify the olitiau as a grotesque species of fruit bat known as the hammer-headed bat Hypsignathus monstrosus. As its name reveals, however, the head and face of this species is extremely long and swollen – wholly dissimilar from the flattened, monkey-like face specifically described by Sanderson and Russell.

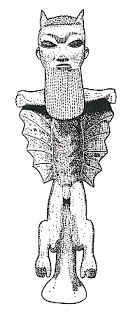

A giant bat-like entity has also been reported from Ghana, where it is known as the sasabonsam. In 1939, a report of a dead specimen was published in the West African Review journal, together with a photograph of an alleged carving of one such beast, which depicted it with relatively short wings and a bearded, humanoid face.

Sketch based upon the above-mentioned photograph of an alleged carving of a sasabonsam (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Sketch based upon the above-mentioned photograph of an alleged carving of a sasabonsam (© Dr Karl Shuker)There are two suborders of bats – the mega-bats (constituting the fruit bats), which include most of the largest species; and the micro-bats (constituting all of the other bats), many of which are much smaller. Consequently, we might expect bats with 12-ft wingspans to be more closely allied to the mega-bats than to the micro-bats. In reality, however, the reverse may well be true.

The flattened monkey or humanoid face of the ahool and the olitiau is particularly interesting, because this is very different from the long-muzzled, distinctly fox-like faces of the fruit bats (hence their alternative name of flying fox), but similar to those of many micro-bats. How extraordinary and zoologically iconoclastic it would be if the world's largest bat species ultimately proved not to be mega-bats but micro-bats!

The flap-ornamented but still unequivocally flat face of a micro-bat – namely, the Antillean ghost-faced bat Mormoops blainvillii (public domain)

The flap-ornamented but still unequivocally flat face of a micro-bat – namely, the Antillean ghost-faced bat Mormoops blainvillii (public domain)Finally: several striking photographs of people holding seemingly enormous bats via their outstretched wings can be readily accessed on the internet. However, close examination of these reveals that in each instance the bat – invariably a fruit bat, some species of which are already fairly large – is being held much closer to the camera than the person who is holding it. As with the hammer-headed bat photograph opening this ShukerNature article, these images are merely clever examples of forced perspective.

So, sadly, if we want to discover a bona fide giant bat, we must look for it not online but rather in the riverside jungles of Africa, or listen out for its unique triple cry amid the shadowy forests of Java.

A selection of sourceless online photographs of supposedly giant bats that in reality are nothing more than examples of forced perspective (© owners presently unknown to me – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational, review purposes only)

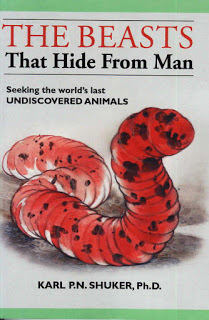

A selection of sourceless online photographs of supposedly giant bats that in reality are nothing more than examples of forced perspective (© owners presently unknown to me – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational, review purposes only) For more information concerning the ahool, olitiau, sasabonsam, and other crypto-bats, be sure to check out my book The Beasts That Hide From Man .

Published on July 29, 2018 07:10

July 14, 2018

HEARKENING BACK TO THE HAZELWORM

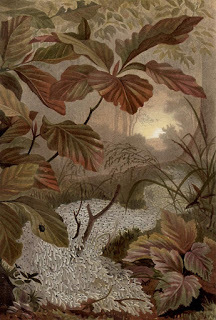

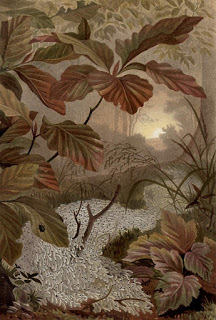

Beautiful 19th-Century chromolithograph of the remarkable phenomenon nowadays believed by zoologists to be the true explanation for bygone reports of the hazelworm (public domain)

Beautiful 19th-Century chromolithograph of the remarkable phenomenon nowadays believed by zoologists to be the true explanation for bygone reports of the hazelworm (public domain)One of the most extraordinary creatures to straddle the boundaries of mythology and reality must surely be the European hazelworm, and yet its fascinating history is all but forgotten today. High time, therefore, to resurrect it from centuries of zoological neglect and present its very curious credentials to a modern-day audience at last.

Back in the Middle Ages, the Germanic folklore of Central Europe's alpine regions contained many tales of a terrifying dragon of the huge, limbless, serpent-like variety known as the worm. But this particular worm was set apart from others by its sometimes hairy rather than scaly outer surface, and above all else by its proclivity for inhabiting areas containing a plenitude of hazel bushes. Consequently, it duly became known as the hazelworm (aka Heerwurm and Haselwurm in German, but not to be confused with a known species of legless lizard, the slow worm Anguis fragilis, which is also sometimes referred to as the hazelworm).

The slow worm, a familiar species of European legless lizard sometimes referred to as the hazelworm (© Wildfeuer/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

The slow worm, a familiar species of European legless lizard sometimes referred to as the hazelworm (© Wildfeuer/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Additionally, Leander Petzoldt reported in his Kleines Lexikon der Dämonen und Elementargeister (2003) that according to some traditional beliefs, the hazelworm was nothing less than the Serpent that had tempted Adam and Eve with fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden, and was therefore also accorded such alternative names as the Paradise Snake and the Worm of Knowledge.

After God had cursed it and banished it for its treachery, however, the Serpent supposedly sought sanctuary in hazel bushes outside Eden, where it feeds to this day upon their foliage, and winds its elongated body around their roots. Moreover, it subsequently became passive in nature, and can readily be recognised by its whitish colouration, thus yielding for it yet another name – the white worm or Weisser Wurm. And because it is said to surface just before the onset of a war, a further name given to this contentious creature is war worm.

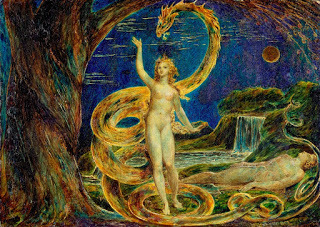

Painting by William Blake depicting Eve with an inordinately lengthy EdenSerpent, reminiscent of medieval reports of the hazelworm (public domain)

Painting by William Blake depicting Eve with an inordinately lengthy EdenSerpent, reminiscent of medieval reports of the hazelworm (public domain)Early retellings of its legends ascribed to the hazelworm an immense body length. Perhaps the most famous example is a local account penned by Rector and Pastor Heinrich Eckstorm (1557-1622) that appeared in Chronicon Walkenredense. Printed in 1617, this was the Latin chronicle of his monastery, Walkenried Abbey, situated in what is today Lower Saxony, Germany. Here is what he wrote.

One day in July 1597, a woman hailing from Holbach ventured into Lower Saxony's Harz mountain range to collect blueberries, but as she ascended she encountered an enormous hazelworm, which scared her so much that she promptly abandoned her basket of diligently-picked berries and fled to the village of Zorge. There she met a woodcutter named Old William, and pleaded with him to give her shelter, which he did, although he and his wife laughed heartily and disbelievingly when the woman told them about the hazelworm.

From the Chronicon Walkenredense (public domain)

From the Chronicon Walkenredense (public domain)Eight days later, however, when inadvertently finding himself in the vicinity of where she had claimed to have seen the monster, Old William himself encountered it, lying across the road up ahead, and so big that he had initially mistaken it for a fallen oak tree – until it began to move, and raise its hitherto-concealed head from out of some nearby hazel bushes. He too duly fled to Zorge, where he told everyone what he had seen.

Old William estimated that the hazelworm had been around 18 ft long, was as thick as a man's thigh, was green and yellow in colour, and, of particular interest, possessed feet on its underparts, rather than being limbless. Several notable personages were present to hear his testimony, including lawyers Mitzschefal from Stöckei and Joachim Götz from Olenhusen, and doctors Johannes Stromer and Philipp Ratzenberg.

Medieval illustration of a hazelworm depicted atypically with wings (public domain)

Medieval illustration of a hazelworm depicted atypically with wings (public domain)Two centuries later, in 1790, Blankenburg-based chronicler Johann Christophe Stübner, a major sceptic of hazelworm reports, nonetheless recorded that the skeleton of a charred hazelworm was supposedly discovered in Wurmberg, a Lower Saxony forestry village near Braunlage. He also noted that in 1782 a lengthy hazelworm could apparently still be found in Allröder Forest.

Conversely, as noted by renowned South Tyrolean folklorist Hans Fink in his book Verzaubertes Land: Volkskult und Ahnenbrauch in Südtirol [Enchanted Land: Folk Art and Alpine Life in South Tyrol] (1969), stories concerning the hazelworm that still abound today in the autonomous South Tyrol (occupying a region formerly part of Austria-Hungary but annexed by Italy in 1919) aver that it is no bigger than a cradle-fitting child in swaddling clothes. (This in turn has led to some confusion with another herpetological alpine cryptid, the tatzelworm – click here to read my ShukerNature article concerning this creature.) There are even claims that it has the head of a child too and can howl like a baby crying.

Model of tatzelworm created by Markus Bühler (© Markus Bühler)

Model of tatzelworm created by Markus Bühler (© Markus Bühler)Also, it was once greatly sought after. As documented by Claudia Liath in Der Grüne Hain[The Green Grove] (2012), this was because anyone eating the flesh of a hazelworm would supposedly become immortal, remaining forever young, handsome, and healthy, and would also gain all manner of other ostensibly desirable but otherwise unobtainable benefits, such as the ability to talk to and understand the speech of animals, to discover hidden treasures, and to be fully versed in the healing properties of plants. Indeed, some of his envious, less gifted contemporaries actually avowed that the extraordinary scholarly abilities of Swiss physician, alchemist, and astrologer Theophrastus Paracelsus (1493/4-1541) must surely be due to his having secretly consumed the meat of a hazelworm.

In Hexenwahn: Schicksale und Hintergründe. Die Tiroler Hexenprozesse [The Witch Delusion: Fates and Backgrounds. The Tyrolean Witch Trials] (2018), Hansjörg Rabanser recorded that during one such trial – that of the alleged sorcerer Mathaus Niderjocher, held at the Sonnenburg district court in 1650/51 - the defendant claimed that he and a locksmith named Andreas had once hunted a hazelworm by magical means. After consulting a book of sorcery, they had drawn a magical circle around a hazel bush, then dug out the bush itself, and found at knee-deep level in the earth a stony plate, beneath which was a hazelworm that was very long, thick, and white in colour. Despite recourse to evocation spells from the book of sorcery, however, they were unable to control or capture the hazelworm, which bit Andreas in the hand before disappearing.

Portrait of Theophrastus Paracelsus, painted by Quentin Massys (public domain)

Portrait of Theophrastus Paracelsus, painted by Quentin Massys (public domain)If such claims as those presented above were factual, there may even be opportunities to repeat them in the present day, judging at least from some tantalising reports of hazelworms having been killed in modern times, as collected and presented in an extensive German-language article on this subject by Swiss chronicler Markus Kappeler (click here to read it).

For example, not far from Ilfeld monastery in Honstein county at the foot of the Harz Mountains are the ruins of a castle named Harzburg, where a hazelworm was reputedly seen for three consecutive years around half a century ago, until killed by two woodcutters there, after which its body was hung from a tree, attracting many interested viewers coming from near and far. It was said to be 12 ft long, with a head reminiscent of a pike's in general form. (Back in 1712, within his major opus Hercynia Curiosa oder Curiöser Hartz-Wald, Dr Georg H. Behrens had claimed that very large, hideous-looking hazelworms inhabited these very same castle ruins.) The skin of another slain hazelworm was allegedly exhibited at one time in Schleusingen, a city in Thuringia, Germany.

A hazel bush of the common hazel Corylus avellana, around whose roots the hazelworm is traditionally believed in alpine folklore to entwine its very lengthy, elongate body (© H. Zell/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A hazel bush of the common hazel Corylus avellana, around whose roots the hazelworm is traditionally believed in alpine folklore to entwine its very lengthy, elongate body (© H. Zell/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Even today, locals inhabiting what was formerly the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg in northwestern Germany (now the Kingdom of Hanover and Duchy of Brunswick) claim that this rangy reptile is still quite common, that it sucks the milk from the udders of cows and poisons the meadows, and that they therefore still go out at certain times of the year to hunt young specimens measuring 3-4.5 ft. Make of that what you will!

For in reality, the mysterious hazelworm has long since ceased to be a mystery, at least for zoologists. Indeed, as far back as the 1770s, physician August C. Kühn documented that sightings of supposed hazelworms were actually based upon observations of long moving columns of army worms – a popular name given to the black-headed, white-bodied larva of Sciara (=Lycoria)militaris and several other dark-winged species of fungus gnat. Subsequent studies by other naturalists swiftly confirmed his statement. The exquisite 19th-Century chromolithograph heading this ShukerNature article and presented again below depicts one such procession (and click here to view a short video of one on YouTube).

An extremely lengthy procession of fungus gnat larvae, nowadays deemed to be the identity of the very long, white-bodied hazelworm of traditional alpine lore (public domain)

An extremely lengthy procession of fungus gnat larvae, nowadays deemed to be the identity of the very long, white-bodied hazelworm of traditional alpine lore (public domain)Columns or processions of these insect larvae moving in a nose-to-tail manner, i.e. each larva following immediately behind another, can measure up to 30 ft long and several inches in diameter (as such columns can each be many larvae abreast). Accordingly, such a procession might well be mistaken for a single enormously lengthy, elongate snake-like entity if seen only briefly or during poor viewing conditions (e.g. at twilight, during mist or fog), and especially if unexpectedly encountered by a layman too terrified to stay around for a closer look!

Similarly, sightings of noticeably hairy hazelworms were ultimately discounted as columns of hairy caterpillars walking in single file and belonging to the pine processionary moth Thaumetopoea pityocampa. The hazelworm was no more, merely a closely-knit procession of insect larvae, not a single, uniform entity in its own right after all.

A single-file procession of processionary moth caterpillars, whose hairy bodies should never be touched as the hairs cause extreme irritation (public domain)

A single-file procession of processionary moth caterpillars, whose hairy bodies should never be touched as the hairs cause extreme irritation (public domain)Of course, the above identification does beg the question: if this is truly all that the hazelworm ever was, how can we explain the reports of exhibited hazelworm skins, a charred hazelworm skeleton, and other physical evidence purportedly originating from this officially non-existent creature?

Nothing more than tall tales and baseless folklore – or a bona fide cryptozoological conundrum still awaiting a satisfactory solution?

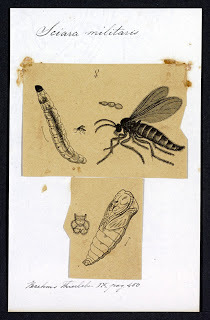

From Iconographia Zoologica, the larva, adult, and pupa of Sciara militaris – the minute origin of a monstrous mystery…? (public domain)

From Iconographia Zoologica, the larva, adult, and pupa of Sciara militaris – the minute origin of a monstrous mystery…? (public domain)

Published on July 14, 2018 04:23

July 4, 2018

WOLVES, JACKALS, COYOTES, AND SOME VERY UNUSUAL 'HILL FOXES' - EXPLORING BRITAIN'S UNOFFICIAL CANINE FAUNA

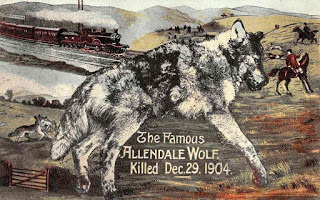

Contemporary picture postcard depicting the infamous Hexham (Allendale) wolf, from my personal collection (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Contemporary picture postcard depicting the infamous Hexham (Allendale) wolf, from my personal collection (© Dr Karl Shuker)Whereas Britain's unofficial feline fauna has attracted immense attention from the media and the general public (albeit rather less so from the scientific community) for several decades now, its equally unrecognised canine contingent has received far less notice, yet is no less intriguing and controversial. To redress the balance somewhat, therefore, here is a selection of UK crypto-canid cases that I have investigated and documented down through the years.

Quite a variety of British mystery dogs have been reported, including some extremely large beasts with decidedly Baskervillian overtones (comparable to the controversial Beast of Gévaudan that terrorised France during the mid-18th Century – click here for my extensive analysis of this highly contentious case). They have often blamed for savage killings of sheep or other livestock.

Reference print for Hound of the Baskervilles (Collection of the National Media Museum, no restrictions)

Reference print for Hound of the Baskervilles (Collection of the National Media Museum, no restrictions)These are surely nothing more unusual than run-wild hounds, or crossbreeds with various of the larger well-established breeds (e.g. mastiff, great dane) in their ancestry. Typical examples reported include an enormous black creature with a howl like a foghorn, hailing from Edale, Derbyshire (Daily Express, 14 October 1925); a beast the size of a small pony sighted on Dartmoor by Police Constable John Duckworth in 1969 and again in 1972 (Sunday Mirror, 22 October 1972); and a sheep-slaughtering marauder stalking the Welsh hamlet of Clyro, Powys (Sunday Express, 10 September 1989). Notably, Clyro is actually the locality of the real Baskerville Hall – its name was borrowed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle for his fictional, Dartmoor-relocated equivalent.

Even today, some remarkably lupine mystery beasts are sighted spasmodically in Staffordshire’s wooded Cannock Chase (e.g. Stafford Post, 30 May 2007). Some have opined that these mystery dogs are wolves. However, according to many authorities, the last verified wolf of mainland Britain died in Scotland during either the late 17th or the early 18th Century (opinions differ as to the precise year, but 1680 and 1743 are two popular suggestions).

The murderous Hound of the Baskervilles as depicted upon the cover of a book by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (public domain)

The murderous Hound of the Baskervilles as depicted upon the cover of a book by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (public domain)Incidentally, long after the last Irish wolf was killed, in County Carlow around 1786, there were rumours that small wolves existed on the Isle of Achill, just off Ireland’s western coast. Traditionally, these have been assumed to be wholly mythical, but in a letter to me of 21 February 1998, British zoologist Clinton Keeling provided a fascinating snippet of information on this subject - revealing that as comparatively recently as c.1904, the alleged Achill Island wolves were stated to be “common” by no less a person that okapi discoverer Sir Harry Johnston.

Also of note here is that according to Michael Goss (Fate, September 1986), when foxes became scarce in a given area, hunters would sometimes release foxes imported from abroad - until as recently as the early 1900s, in fact - and that in some cases it seems that these imported ‘foxes’ were really jackals or young wolves.

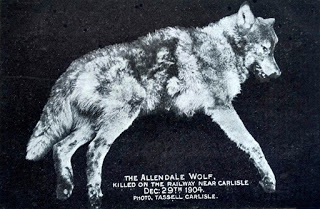

Second contemporary picture postcard depicting the Hexham (aka Allendale) wolf (public domain)

Second contemporary picture postcard depicting the Hexham (aka Allendale) wolf (public domain)A supposed grey wolf Canis lupus blamed for numerous livestock killings near Monmouthshire’s Llanover Park in 1868 was never obtained (The Field, 23 May 1868). Conversely, after a long hunt during winter 1904 for an unidentified sheep-killer in Hexham and Allendale, Northumberland, a wolf was finally found - discovered dead, on 29 December 1904, upon a railway line near Carlisle. As John Michell and Robert Rickard discussed in Living Wonders (1982), it was initially thought to have been an escapee belonging to a Captain Bain (sometimes named as Bains) of Shotley Bridge, near Newcastle, which had absconded in October, but his wolf had only been a cub, whereas the dead specimen was fully grown. A visiting American later claimed that the Hexham wolf’s head, preserved by a taxidermist, was actually that of a husky-like dog called a malamute, but several experts strenuously denied this.

When the supposed wolf responsible for several sheep attacks between Sevenoaks and Tonbridge in 1905 was shot by a gamekeeper on 1 March (Times, 2 March 1905), it proved to be a jackal C. aureus. Interestingly, as noted by Alan Richardson of Wiltshire (The Countryman, summer 1975), an entry in the Churchwardens’ Accounts for the village of Lythe, near Whitby, North Yorkshire, recorded that in 1846 the sum of 8 shillings was paid for “One jackall [sic] head”. As this was a high price back in those days, it suggests that whatever the creature was, it was unusual. By comparison, fox heads only commanded the sum of four shillings each at that time.

The common or golden jackal C. aureus (© Thimindu/Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

The common or golden jackal C. aureus (© Thimindu/Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)In May 1883, R. Payze met some men travelling to London, who had caught three very young, supposed fox cubs while passing through Epping Forest. Payze bought one, naming it Charlie, but as he grew older it became clear that Charlie was not a fox. When shown by Payze to A.D. Bartlett, London Zoo’s superintendent, Charlie was readily identified by Bartlett as C. latrans, North America’s familiar coyote or prairie wolf.

After receiving Charlie for the zoo, Bartlett investigated his origin, and learnt that a few years earlier four coyote cubs had been brought to England in a ship owned by J.R. Fletcher of the Union Docks. They were kept for a few days at the home of a Colonel Howard of Goldings, Loughton, then taken to Mr Arkwright, formerly Master of the Essex Hunt, and released in Ongar Wood, which joins Epping Forest. Bartlett found that the local people acquainted with this forest well recalled the release of the coyotes, which they termed the ‘strange animals from foreign parts’ (The Naturalist’s World, 1884).

To the untrained eye, some coyotes can look superficially vulpine (© Justin Johnsen/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

To the untrained eye, some coyotes can look superficially vulpine (© Justin Johnsen/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)Charlie was clearly a first-generation offspring of two of these original four; and those, or their descendants, no doubt explained the periodic reports thereafter from this region regarding grey fox-like beasts, occasionally spied yet never caught by the hunt - but how did this strange saga end? Did Epping’s coyotes simply die out, or did they establish a thriving lineage? And, if so, could there still be coyotes here today?

Intriguingly, in the Countryman (summer 1958), Doris W. Metcalf recalled having seen some very large, grey-furred wolf-like beasts near Jevington prior to World War II; she had assumed that they must be “the last of an ancient line of hill foxes”, or perhaps some surviving fox-wolf hybrids (but fox-wolf crossbreeding does not occur, and even it if did, it is highly unlikely that any resulting offspring would be viable). In May 1974, a similar animal, said to be 2 ft tall with a distinctly fox-like tail, was spied by Thomas Merrington and others as it slunk around the shores of Hatchmere Lake and the paths in Delamere Forest, Kingsley (Runcorn Weekly News, 30 May 1974).

A grey-coated coyote, the identity of Jevington's 'hill foxes'? (© Dawn Beattie/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

A grey-coated coyote, the identity of Jevington's 'hill foxes'? (© Dawn Beattie/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)When the Isle of Wight’s mystifying lion-headed ‘Island Monster’, allegedly maned but otherwise virtually hairless, was finally shot in 1940, it proved to be an old fox in an advanced state of mange; almost all of its fur had been lost, except for some still covering its neck, creating the illusion of a mane (Isle of Wight County Press, 24 February 1940). During the 1980s, Exmoor naturalist Trevor Beer was shown the carcass of a strange grey fox killed at Muddiford; its pelage consisted almost entirely of grey under-fur (hence the fox’s odd colour) - due to disease-induced hair loss, or perhaps a mutant gene? (There is on record a rare mutant morph of the red fox Vulpes vulpes known as the woolly fox in which the harsher outer coat is indeed largely or entirely absent, with only the softer, woollier under-fur present.)

In January 1990, a peculiar fox-like beast with blue-grey fur was spotted seeking food in a snow-covered field at Cynwyd, Corwen, in North Wales, by farmer Trefor Williams; after capturing it with a lasso, he brought it home. His unexpected find, duly christened Samantha, was a blue-phase Arctic fox Alopex lagopus, another species not native to Britain (Daily Post, 2 February 1990). Back in March 1983, an Arctic fox had been killed at Saltaire, West Yorkshire, by David Bottomley’s collie (Sunday Express, 6 March). Their origins are unknown.

Blue fox – i.e. an Arctic fox exhibiting its blue-phase summer coat (public domain)

Blue fox – i.e. an Arctic fox exhibiting its blue-phase summer coat (public domain)In February 1994, an Arctic fox was discovered in the courtyard of Dudley Castle, in whose grounds stands Dudley Zoo, but it had not escaped from there. Yet again, its origin remains undetermined (Wolverhampton Express and Star, 15 February 1994).

So too does that of the female Arctic fox shot in the early hours of 13 May 1998 by a farmer from Alnwick, Northumberland, after he discovered it eating one of his lambs; its body was later preserved and mounted by local taxidermist Ralph Robson (Fortean Times, September 1998). Curiously, just three months earlier, a male Arctic fox had been shot less than 30 miles away. Could these have been an absconded pair?

Arctic fox exhibiting its more familiar white-phase winter coat (public domain)

Arctic fox exhibiting its more familiar white-phase winter coat (public domain)Finally: On the evening of 13 March 2010, cryptozoological correspondent Shaun Histed-Todd was driving a bus along a Dartmoor road when he saw a most unusual creature run down the edge of the moor and stand at the road side, where the bus’s headlights afforded him an excellent view of it for roughly half a minute before it ran back up onto the moors (Shaun has asked me not to make public the precise location, to protect the animal). Shaun contacted me a few days later, as he was unable to identify it, and provided me with a detailed description, whose most notable features were as follows. It resembled a young fox and had a bushy white-tipped tail, but its coat was dark silvery-grey, it had noticeably large ears, white paws, and a black raccoon-like facial mask. Reading this, I was startled to realise that Shaun’s description was an exact verbal portrait of a most unusual yet highly distinctive animal – a young platinum fox. After checking photos of platinum foxes online, Shaun confirmed that this is indeed what he had seen.

Arising in 1933 as a mutant form of the silver fox (itself a mutant form of the red fox), its extraordinarily beautiful and luxuriant fur meant that platinum foxes were soon being bred in quantity on fur farms as their pelts became highly prized. But what was a platinum fox doing on Dartmoor, where, as far as I know, there are no fur farms? The platinum condition results from a dominant mutant allele (gene form), and as it has arisen spontaneously in many unrelated, geographically-scattered fox litters since 1933, perhaps it has done so again, quite recently, in a litter of Dartmoor foxes. Shaun has since learned of other sightings of this animal, with one made only 2 miles away from the site of his own observation.

Platinum fox pelt (public domain)

Platinum fox pelt (public domain)Clearly, Britain's unofficial canine fauna may have more surprises still in store for us.

This ShukerNature blog article is an expanded version of various extracts from my books Extraordinary Animals Revisited and Karl Shuker's Alien Zoo .

A third contemporary picture postcard depicting the Hexham (Allendale) wolf (public domain)

A third contemporary picture postcard depicting the Hexham (Allendale) wolf (public domain)

Published on July 04, 2018 20:48

June 2, 2018

REMEMBERING THE ANDEAN WOLF - A WOLF IN SHEEPDOG'S CLOTHING?

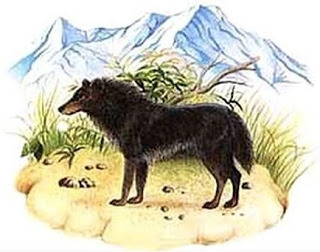

Artist reconstruction of the Andean wolf's possible appearance in life (artist identity and © unknown to me, image present

here

on The Full Wiki; reproduced here on ShukerNature upon a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational purposes only)

Artist reconstruction of the Andean wolf's possible appearance in life (artist identity and © unknown to me, image present

here

on The Full Wiki; reproduced here on ShukerNature upon a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational purposes only)Welcome to another contribution to this intermittent series of early cryptozoological and other anomalous animal articles of mine exclusively reproduced here on ShukerNature from their now-defunct original British and continental European magazines. It documents a longstanding canine mystery beast known variously as the Andean wolf or Hagenbeck's wolf, discovered by professional animal collector Lorenz Hagenbeck and first brought to scientific attention by German zoologist and pioneering cryptozoologist Dr Ingo Krumbiegel.

Krumbiegel's illustrative comparisons between the imagined appearance in life of the Andean wolf (left) and its postulated relative the maned wolf (right) (public domain)

Krumbiegel's illustrative comparisons between the imagined appearance in life of the Andean wolf (left) and its postulated relative the maned wolf (right) (public domain)This article of mine was first published in the July-August 1996 issue of a long-discontinued bimonthly British magazine entitled All About Dogs, and was the very first publication to include a colour photograph of this cryptid's distinctive (albeit by now somewhat faded) pelt (a few months later it also appeared in my book The Unexplained , published in November 1996).

My July-August 1996 article re the Andean wolf from All About Dogs – please click its image to enlarge it for reading purposes [NB - for Cabreera, read Cabrera] (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My July-August 1996 article re the Andean wolf from All About Dogs – please click its image to enlarge it for reading purposes [NB - for Cabreera, read Cabrera] (© Dr Karl Shuker)The skull attributed by Krumbiegel to the Andean wolf was lost during World War II, but it had already been discounted by some zoologists as having originated from a domestic dog. As for the pelt: sixteen years after my above article was published, I included the following brief update regarding this controversial canid as part of its coverage within my book The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals (2012):

In 2000, an attempt was made to analyse DNA samples from the pelt. Unfortunately, the outcome was unsatisfactory, because the samples were found to be contaminated somehow with dog, wolf, human, and even pig DNA, and to make matters worse still, the pelt had been chemically treated.

However, DNA analysis techniques have vastly improved since 2000, so for quite some time I still had high hopes that further studies of this nature upon the Andean wolf's unique pelt would take place and in turn provide a more satisfactory, precise outcome. Yet as far as I am aware, no additional investigations of it have occurred to date. Nevertheless, based upon earlier findings noted here, it does seem more likely that its pelt is indeed from a domestic dog (albeit of undetermined breed or crossbred heritage) rather than, as originally postulated by Krumbiegel, from a distinct species (and genus) in its own right.

A maned wolf (© Markus Bühler)

A maned wolf (© Markus Bühler)

Published on June 02, 2018 06:03

May 14, 2018

A NEW DAWN FOR THE SUN DOG?

A pre-Inca Peruvian depiction of the New World's mythical sun dog (public domain)

A pre-Inca Peruvian depiction of the New World's mythical sun dog (public domain)Continuing my intermittent series of early cryptozoological and other anomalous animal articles of mine reproduced here on ShukerNature from their defunct original British and continental European magazines, here is one that was first published in the May-June 1997 issue of a long-discontinued bimonthly British magazine entitled All About Dogs.

Photograph of American zoologist and writer A. Hyatt Verrill (public domain)

Photograph of American zoologist and writer A. Hyatt Verrill (public domain) It concerns a mysterious pet once owned by American zoologist and writer A. Hyatt Verrill (1871-1954), and which in his view may constitute a living representative of the supposedly entirely mythological sun dog of Mexico, Mesoamerica, and South America. He dubbed his enigmatic pet 'the Monster', and here is a drawing of it from life, prepared by Verrill himself, as it appeared in his book America's Ancient Civilisations (1953):

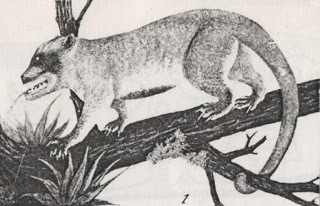

'The Monster' as drawn from life by A, Hyatt Verrill during his ownership of it (© A. Hyatt Verrill – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial educational Fair Use basis for review purposes only)

'The Monster' as drawn from life by A, Hyatt Verrill during his ownership of it (© A. Hyatt Verrill – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial educational Fair Use basis for review purposes only)And here now is my two-page All About Dogs article investigating the sun dog and Verrill's associated claims concerning his pet:

My All About Dogs article from the May-June 1997 issue re the mythological New World sun dog and Verrill's unusual pet - please click images to enlarge for viewing and reading purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My All About Dogs article from the May-June 1997 issue re the mythological New World sun dog and Verrill's unusual pet - please click images to enlarge for viewing and reading purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker)In 2003, I included a coverage of this same subject, inspired by my above article, in a chapter on canine controversies contained within my book The Beasts That Hide From Man .

NB - Please note that these early articles of mine are being reproduced here for their historical interest; their content may be outdated in places, hence my mentioning above the later account of this subject that appears in my Beasts book.

A photograph taken by A. Hyatt Verrill of his pet 'monster' (© A. Hyatt Verrill – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial educational Fair Use basis for review purposes only)

A photograph taken by A. Hyatt Verrill of his pet 'monster' (© A. Hyatt Verrill – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial educational Fair Use basis for review purposes only)

Published on May 14, 2018 07:38

April 18, 2018

DEMYSTIFYING THE DODO OF NAZARETH

An adult female specimen of the dodo's closest relative, the Rodrigues solitaire, as drawn in 1708 by French explorer François Leguat and thereby constituting the only illustration of this now-extinct flightless species prepared by someone who directly saw it in the living state (public domain)

An adult female specimen of the dodo's closest relative, the Rodrigues solitaire, as drawn in 1708 by French explorer François Leguat and thereby constituting the only illustration of this now-extinct flightless species prepared by someone who directly saw it in the living state (public domain)The Indian Ocean's Mascarene archipelago – of which the islands of Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues are its largest, principal members – has acquired everlasting fame as the former home of one of the world's most celebrated and curious subfamilies of extinct birds. I refer, of course, to those flightless hook-billed pigeons of gargantuan stature and grotesque appearance known to zoologists as Raphinae but to everyone else as the dodos and solitaires.

Indeed, the dodo of Mauritius, Raphus cucullatus (the still commonly-applied but obsolete genus Didus being a junior synonym of Raphus), has become the modern-day epitome of obsolescence. "As dead as the dodo" is the ultimate phrase used to describe anything, avian or otherwise, that is irrevocably dated, destroyed, or deceased.

The most ironic aspect of the dodos' extinction is that at one time there was every opportunity to save them. Quite a number of dodos were brought back to Europe, and unlike so many of the tropics' much more delicate avifauna they appeared to be physiologically robust.

Indeed, as David Day pertinently remarked in The Doomsday Book of Animals (1981), any birds that could survive the rough sea voyages of the 17th Century had to be tough. (There is even a confirmed record of a living dodo that reached the Japanese city of Nagasaki in 1647, which is the last recorded dodo specimen in captivity.)

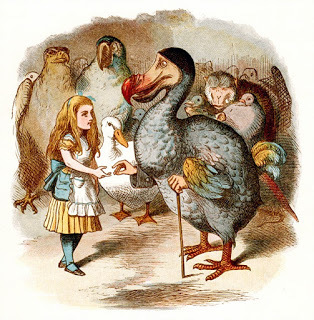

Sir John Tenniel's famous illustration of Alice with the Dodo and other caucus race competitors, from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865); modern, zoological reconstructions of the dodo favour a sleeker, less plump appearance for it (public domain)

Sir John Tenniel's famous illustration of Alice with the Dodo and other caucus race competitors, from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865); modern, zoological reconstructions of the dodo favour a sleeker, less plump appearance for it (public domain)Furthermore, some apparently survived for a number of years in their new European homes. If serious attempts had been made to save them by captive breeding, the existence of these Alice-in-Wonderland birds within today's parklands and gardens may well have been a firm reality instead of an intangible romantic fantasy. Yet no such attempt was made.

Instead, the Mauritius dodo is generally believed to have died out in or around 1681. Moreover, this species' Mascarene relative - the still-sizeable but rather more streamlined solitaire of Rodrigues, Pezophaps solitaria- apparently followed it into oblivion by the latter part of the 18th Century.

A third once-recognised species, the Réunion solitaire Raphus solitarius, which died out at much the same time as its Rodrigues namesake, is nowadays deemed to have been a species of ibis, not a dodo or solitaire at all, and has been reclassified accordingly.

Moreover, a fourth erstwhile species, Réunion's supposed white dodo Victoriornis imperialis, has been thoroughly traduced and entirely discredited taxonomically. I plan to document these two discounted forms in a future ShukerNature article.

Life-sized models of the Réunion white dodo (confusingly labelled alternatively as the solitaire, which on Réunion was a separate but equally non-existent raphine species) and the Mauritius dodo at Tring Natural History Museum (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Life-sized models of the Réunion white dodo (confusingly labelled alternatively as the solitaire, which on Réunion was a separate but equally non-existent raphine species) and the Mauritius dodo at Tring Natural History Museum (© Dr Karl Shuker)Even so, is it possible that some raphine representatives survived beyond these officially-recognized dates of extinction, persisting instead into much more recent times? Let us consider the intriguing if highly-convoluted case of the Nazareth dodo.

Although Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues are without doubt the largest and best known Mascarene islands, they are not the only ones contained within this particular Indian Ocean archipelago. To the north of its major trio lie many far smaller and much less familiar islets and banks. Indeed, most of these have never been explored or even inhabited by humans. Yet at least one could be of considerable significance to the possibility of recent dodo survival.

In 1638, French explorer François Cauche led an expedition to Mauritius and later wrote a detailed account of his adventures. In it, he referred to "oiseaux de Nazaret" ('birds of Nazareth') in relation to dodos. Consequently, several subsequent books included mention of a new species - Didus nazarenus – the Nazareth dodo. But where was Nazareth? What exactly did it mean? Was it the name of some mysterious island? Or could it have been merely a mistranslation of some descriptive phrase used in connection with ordinary dodos? It was all most bewildering.

In his book The Lungfish and the Unicorn(1941), republished in expanded form as The Lungfish, the Dodo and the Unicorn in 1948, Willy Ley, a German-born scientist and science writer much interested in cryptozoology (or what he quaintly referred to as 'romantic zoology'), re-examined the confusing case of the Nazareth dodo. He favoured the last-mentioned explanation as the most likely solution.

My copy of Willy Ley's book The Lungfish, the Dodo and the Unicorn (© Dr Karl Shuker/Viking Press)

My copy of Willy Ley's book The Lungfish, the Dodo and the Unicorn (© Dr Karl Shuker/Viking Press)The first European explorers of Mauritius were Dutch, and these had referred to the dodos as "Walghvogel" ('nauseating birds'), on account of their less-than-tasty flesh. Ley observed that the translation of this into French was "oiseaux de nausée", which sounds similar to "oiseaux de Nazaret".

Added to this is the fact that Ley could find no evidence (at first) for the existence of a Nazareth Island - except for a few ancient maps carrying the name, and he dismissed its presence on these maps as nothing more than a synonym for one of the major Mascarene islands. However, the position of 'Nazareth Island' as marked on these did not correspond with the known location of any of the major Mascarenes - a puzzling inconsistency that Ley explained away as cartographical inaccuracy.

And so, according to Ley, Cauche had mistaken "oiseaux de nausée" for "oiseaux de Nazaret", with Nazareth being nothing more than an alternative name for one of the three principal Mascarenes. All of this seemed eminently plausible - until, as he would reveal in his later book Exotic Zoology (1959), Ley discovered that a 'Nazareth Island' totally separate from these latter islands really did exist.

It turned out that this was the name that early Portuguese sailors had given to a tiny islet called the Île Tromelin. Of 54° 25' E longitude and 15° 51' S latitude, this is a remote diminutive island (less than three miles long) lying approximately 375 miles northwest of Mauritius, 250 miles east of Madagascar, and sited within the Mascarene Basin. Even more stimulating than his identification of Tromelin as the mysterious 'Nazareth Island', however, was Ley's discovery that the 19th-Century Dutch zoologist and dodo expert Dr Anthonie Cornelius Oudemans (who was also a diligent if derided chronicler of sea serpent reports – click here ) had suggested that Tromelin may be worth exploring in search of fossil (and even living) dodos!

Willy Ley (public domain)

Willy Ley (public domain)As he noted in a full report in his book Searching For Hidden Animals (1980), veteran cryptozoologist and university-based biochemist Prof. Roy Mackal had followed up the history of the Nazareth dodos and Ley's corresponding researches very closely. Consequently, intrigued by the zoological potential ascribed to Tromelin by Oudemans, Prof. Mackal set out to learn more about this mysterious islet.

He discovered from a nautical chart depicting the isle (and produced from a Madagascan survey of the area carried out in 1959) that its only links with humanity were its ownership by France and its possession of a small airstrip plus a meteorological station (apparently of automatic type). Nothing seemed to be known of its wildlife.

Thanks to the vast information resources that have been made readily available via the internet in the decades that have passed since Mackal's book was published, conversely, this latter statement is no longer true.

As confirmed by a factsheet devoted to Tromelin produced and updated by BirdLife International (click here to access it), we now know that this tiny isle, currently an unmanned nature reserve but with four permanent staff in attendance at the meteorological station, is home to two significant populations of seabird – the masked booby Sula dactylatra and the red-footed booby S. sula. It is also used for roosting purposes by frigate birds (two different species of which formerly bred here), but according to the factsheet there are no resident land birds. There are, however, brown rats, which have reached the isle via ships, and which have to be poisoned periodically in order to keep their numbers down.

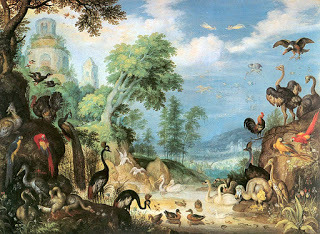

Roelant Savery's beautiful painting 'Landscape with Birds', produced in 1628, which includes among its diverse avian array a dodo, standing just in front of a cassowary and to the immediate left of a heron (public domain)