Kathy Brandt's Blog, page 3

August 1, 2013

Kathy and Max interviewed on Denver 9 News about their memoir, Walks On The Margins

My son, Max, and I talked about our memoir, Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar illness on Denver 9 News. Click on the video below.

Kathy and Max do an interview on Denver 9 News about their memoir, Walks On The Margins

My son, Max, and I talked about our memoir, Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar illness on Denver 9 News. Click on the video below.

July 6, 2013

The Contract of Your Birth. A Mom & Son Story of Surviving Bipolar llness

First published on KRCC Public Radio “The Middle Distance” July 5, 2013

The Contract of Your Birth

by Kathryn Eastburn

For the past few years, I have been part of a monthly lunch group of women who write, read and love books. When we get together, we begin talking about our work, but the conversation quickly shifts to family concerns: How are the kids? The elderly parents? Who’s having a baby? Getting married? Who’s got a new job?

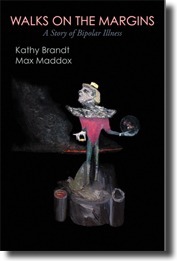

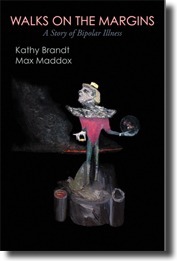

Throughout this time, one of our group has been working on a book with her son who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder while he was a college student at Grinnell College in 1999. Kathy Brandt and Max Maddox’s collaboration is now published, following several years of writing, editing and rewriting, preceded by years of psychiatric crises that strained and stretched and ultimately fortified the bond between this remarkable mother and son.

Their story, Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar Illness, told with brutal honesty, great skill and sweeping passages of lyric beauty, is nothing short of a landmark in the literature of mental illness.

Brandt, a longtime resident of the Springs area, had written and published before, a series of mysteries set in blue Caribbean waters with a scuba-diving private investigator protagonist. Maddox, a painter and art instructor in Denver, hadn’t written before except for academic term papers, but took to it with a true artist’s eye and ear. They settled on a structure that alternates voices from chapter to chapter, revealing the impact of Max’s bipolar illness on mother and son from their unique points of view.

The book succeeds on several levels, not the least of which is the alternating rhythm of those voices, Kathy’s steady and under-stated, Max’s lush with imagery. The book begins with Max’s first psychotic break: “It was just before sunrise at the electric blue hour I had come to appreciate in the week since I had given up sleeping,” he says. His behavior had grown increasingly erratic until he was finally picked up by the police, sent to a Des Moines hospital and evaluated by a medical team: “I told them who I was (everyone) and where I was from (everywhere), crying into my hands as the lady in white scribbled out a few notes, enough syndromes for a diagnosis.”

Kathy and her husband drive Max home to Colorado with a bag full of medication and get “a thorough introduction to the throes of mania and a crash course on parenting a son with manic depression.”

Unfamiliar as yet with the course of bipolar illness, Brandt indulges in a moment of magical thinking. “At home,” she says, “my plans were simple. I’d roast chicken and heap mashed potatoes onto his plate. I’d dish up huge bowls of strawberry ice cream, brew herb teas, and heat warm milk and Max would sleep. When he woke, he would be my son again.”

The chapters that follow chronicle Max’s cycles through episodes of mania and depression, vividly and urgently recalled, and Kathy’s growing understanding of the pitfalls of a mental health care system plagued by chronic underfunding and lack of coordination. Max is manhandled and abused in the course of one emergency hospitalization, and told that he doesn’t meet the criteria for admission in the midst of another crisis. His mother, meanwhile, seeks knowledge and understanding, mobilizing her efforts to become an expert caregiver, despite frustrations and setbacks.

Brandt is clear-eyed about the disease and its implications, but determined not to fall into the trap of assuming incurable means hopeless. She becomes deeply involved in classes for families through her local NAMI chapter (National Alliance on Mental Illness), imparting the message that, with adequate support, “ … people with mental illness can and do succeed. They live fulfilled lives, working and developing significant relationships. They engage in the process of recovery, knowing that recovery doesn’t mean cure.”

Max, too, is realistic about both the struggle and the invaluable gift of family support. In a late chapter, his mother arrives at his apartment during a depressive episode when he has battled suicidal thoughts.

“And yet,” he says, “my mom was there with me still, sitting on the bed next to me in my basement cave, when I opened my acceptance letter to graduate school, the application for which she did a wonderful job.

‘Thank God,’ she and I said in the same breath. She had ushered me back into life once again. What can I say without resorting to cliché? I can’t. Really though, you don’t have to bring everyone down with you. But, of course, this means not going down at all. And so there is the contract of your birth.”

Sidebar:

Walks on the Margins: A Story of Biploar Illness by Kathy Brandt and Max Maddox (Monkshood Press, 2013). Available in print and Kindle editions.

Please join the authors for a book release and signing party, July 14, 3-5 p.m. Poor Richard’s patio, 324 ½ North Tejon Street, Colorado Springs.

The Contract of Your Birth

First published on KRCC Public Radio “The Middle Distance” July 5, 2013

The Contract of Your Birth

by Kathryn Eastburn

For the past few years, I have been part of a monthly lunch group of women who write, read and love books. When we get together, we begin talking about our work, but the conversation quickly shifts to family concerns: How are the kids? The elderly parents? Who’s having a baby? Getting married? Who’s got a new job?

Throughout this time, one of our group has been working on a book with her son who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder while he was a college student at Grinnell College in 1999. Kathy Brandt and Max Maddox’s collaboration is now published, following several years of writing, editing and rewriting, preceded by years of psychiatric crises that strained and stretched and ultimately fortified the bond between this remarkable mother and son.

Their story, Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar Illness, told with brutal honesty, great skill and sweeping passages of lyric beauty, is nothing short of a landmark in the literature of mental illness.

Brandt, a longtime resident of the Springs area, had written and published before, a series of mysteries set in blue Caribbean waters with a scuba-diving private investigator protagonist. Maddox, a painter and art instructor in Denver, hadn’t written before except for academic term papers, but took to it with a true artist’s eye and ear. They settled on a structure that alternates voices from chapter to chapter, revealing the impact of Max’s bipolar illness on mother and son from their unique points of view.

The book succeeds on several levels, not the least of which is the alternating rhythm of those voices, Kathy’s steady and under-stated, Max’s lush with imagery. The book begins with Max’s first psychotic break: “It was just before sunrise at the electric blue hour I had come to appreciate in the week since I had given up sleeping,” he says. His behavior had grown increasingly erratic until he was finally picked up by the police, sent to a Des Moines hospital and evaluated by a medical team: “I told them who I was (everyone) and where I was from (everywhere), crying into my hands as the lady in white scribbled out a few notes, enough syndromes for a diagnosis.”

Kathy and her husband drive Max home to Colorado with a bag full of medication and get “a thorough introduction to the throes of mania and a crash course on parenting a son with manic depression.”

Unfamiliar as yet with the course of bipolar illness, Brandt indulges in a moment of magical thinking. “At home,” she says, “my plans were simple. I’d roast chicken and heap mashed potatoes onto his plate. I’d dish up huge bowls of strawberry ice cream, brew herb teas, and heat warm milk and Max would sleep. When he woke, he would be my son again.”

The chapters that follow chronicle Max’s cycles through episodes of mania and depression, vividly and urgently recalled, and Kathy’s growing understanding of the pitfalls of a mental health care system plagued by chronic underfunding and lack of coordination. Max is manhandled and abused in the course of one emergency hospitalization, and told that he doesn’t meet the criteria for admission in the midst of another crisis. His mother, meanwhile, seeks knowledge and understanding, mobilizing her efforts to become an expert caregiver, despite frustrations and setbacks.

Brandt is clear-eyed about the disease and its implications, but determined not to fall into the trap of assuming incurable means hopeless. She becomes deeply involved in classes for families through her local NAMI chapter (National Alliance on Mental Illness), imparting the message that, with adequate support, “ … people with mental illness can and do succeed. They live fulfilled lives, working and developing significant relationships. They engage in the process of recovery, knowing that recovery doesn’t mean cure.”

Max, too, is realistic about both the struggle and the invaluable gift of family support. In a late chapter, his mother arrives at his apartment during a depressive episode when he has battled suicidal thoughts.

“And yet,” he says, “my mom was there with me still, sitting on the bed next to me in my basement cave, when I opened my acceptance letter to graduate school, the application for which she did a wonderful job.

‘Thank God,’ she and I said in the same breath. She had ushered me back into life once again. What can I say without resorting to cliché? I can’t. Really though, you don’t have to bring everyone down with you. But, of course, this means not going down at all. And so there is the contract of your birth.”

Sidebar:

Walks on the Margins: A Story of Biploar Illness by Kathy Brandt and Max Maddox (Monkshood Press, 2013). Available in print and Kindle editions.

Please join the authors for a book release and signing party, July 14, 3-5 p.m. Poor Richard’s patio, 324 ½ North Tejon Street, Colorado Springs.

July 2, 2013

The Case Against Excessive Use of Antipsychotics

Robert Whitaker, author of Mad in America, spoke to a full house at the NAMI Conference in San Antonio on Saturday. For many his message was a hard one to hear. I was among them, a parent, whose son, Max, sat beside me. He’s been on and off antipsychotics for more than ten years to treat the psychosis that comes with his bipolar episodes. Whitaker was telling us that might have been a mistake. The key word being might. His review of various research studies seems to indicate that a significant percentage of those with schizophrenia who did not receive antipsychotics or took them for a very limited time had better long- term outcomes than those who took them on an ongoing basis.

We all know that for years antipsychotics have been the medications of choice and that most of those with schizophrenia have been told they would need to stay on them forever. The research seemed to back that up. Yet Whitaker’s review found that those studies were flawed. Worse, he says that using antipsychotics long term makes one more vulnerable to future psychosis. It’s called “oppositional tolerance.” While antipsychotics initially block the uptake of dopamine (the substance believed to cause problems), our brains eventually find ways to adjust, building new receptors and becoming even more sensitive to dopamine. So what did I hear? I heard that the medicine that was supposed to make those with schizophrenia better was making them worse. Long term use of antipsychotics wasn’t just ineffective, it was dangerous.

I resisted this message. Though the studies he cited applied to schizophrenia, I couldn’t help wondering how it applied to my son with bipolar disorder. I’m pretty sure every parent, family member, and person with mental illness who was taking antipsychotics was asking the same thing. I’m not going to rehash Whitaker’s findings here. You can find them elsewhere on the web or at NAMI.org/conference.

As a parent, I wanted to find flaws and I have many questions:

Does Whitaker’s review of the research tell the full story? Are there gaps? Is there contradictory evidence?

Does it apply to illnesses other than schizophrenia?

What particular antipsychotics were included in the studies? Is it necessarily true that all have the same outcomes?

If his findings are correct, then what do we do about it? Should those on antipsychotics be slowly weaned?

If there have in fact been brain changes as a result of the medication, can they be reversed?

And how on earth do we treat people who are psychotic if not with antipsychotics?

But in the end, his research was compelling. Even more so when I heard that Finland, which adopted selective-use protocol of antipsychotics in 1992, has the best-documented long-term results in the western world. I feel that NAMI has the responsibility to support further investigation and open up the discussion for a full airing from all stakeholders.

Whitaker’s findings, if true, would require a new paradigm of treatment, one that might require that someone who is psychotic be given “asylum,” or “refuge,” a place to rest and recover with limited or no antipsychotics, using other effective treatments that include more than just medication. That seems impossible in our country, where the mental health care system is practically non-existent; where people are hospitalized for 3-5 days and released with a bag of samples and prescriptions; where insurance companies dictate release, arguing that recovery can take place outside of the hospital; and where too many psychiatric units are just holding tanks where little good treatment occurs. If Whitaker’s findings prove true, it will take decades to address them and it will take money. How can that happen in a country where we don’t provide even minimal care and where funding continues to be cut?

By the time Whitaker concluded his talk, the room was heavy with anger, despair, and fear. Some people were angry at Whitaker for presenting studies that could prove inaccurate and yet could have such an impact on so many. Others were angry at psychiatrists and big pharma for promoting medication that could be harmful. Most difficult for those with mental illness and their families, me included, was the fear that the medicine we have relied on was damaging and that we had put our trust in the wrong hands.

My son, who as you’ll remember was sitting right beside me during Whitaker’s talk, is angry, very angry about what he heard, angry at doctors and the pharmaceutical industry. And I am scared that he will decide to quit taking the one antipsychotic he is on, and I’m confused about whether he should. He’s been stable, healthy, and happy for several years. What will happen if he stops? Will he fall back into the pit of mania and psychosis, end up on the streets as has happened so many times before? He’s agreed he’ll speak with his doctor about what he’s heard, but I find myself wishing that our family could move to Finland.

** I welcome your comments about this difficult and controversial issue.

June 23, 2013

8 Tips for Writing a Memoir

When my son, Max, and I began work on our memoir,  Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar Illness, we knew we wanted to tell the story from each of our individual perspectives. He would write from the inside of his illness, showing readers just what it’s like to be manic, psychotic, and depressed. I would write from the outside, narrating my fear and my determination to find help. But of course, there was more to our story than points of view, much of which we figured out as we wrote. That was fine with me. As a writer, I’ve always felt that one needs to write to figure out what one really means and needs to say. I take comfort in E.M. Forster who asked,

Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar Illness, we knew we wanted to tell the story from each of our individual perspectives. He would write from the inside of his illness, showing readers just what it’s like to be manic, psychotic, and depressed. I would write from the outside, narrating my fear and my determination to find help. But of course, there was more to our story than points of view, much of which we figured out as we wrote. That was fine with me. As a writer, I’ve always felt that one needs to write to figure out what one really means and needs to say. I take comfort in E.M. Forster who asked,  “How can I know what I think, until I see what I say?” And rewriting is in my bones. Max’s too. But having said that, we realized along the way that there were tools we could implement to make the process a bit less painful.

“How can I know what I think, until I see what I say?” And rewriting is in my bones. Max’s too. But having said that, we realized along the way that there were tools we could implement to make the process a bit less painful.

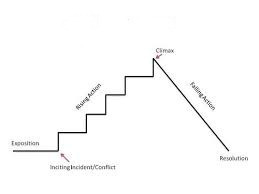

Though this was Max’s first book, I’ve published four novels. I know what a story arc is. But I hadn’t thought to apply it as we worked on the memoir. After all memoirs are non-fiction, a story of what happened, the story of one’s struggle. Why would we use the elements of fiction for non-fiction? I’m sure right now some of you are muttering under your breath “stupid Kathy, you should have known that!” Yeah, I should have. If I’d kept the story arc in mind when we started, we would have saved ourselves a lot of fumbling. Though it wouldn’t have made the story any easier to tell, we would have been focused a bit sooner, drafting a story arc early and reworking with each new draft. So my advice to anyone writing a memoir: Remember to consider the story arc.

Simple Story Arc

What is the story arc? It’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. In his book Screenplay, Syd Field calls it the dramatic structure “a linear arrangement of related incidents, episodes, or events leading to a dramatic resolution.” When I write fiction, I eventually diagram the book on a long sheet of paper—a time line with each incident or plot point rising to the final climax and resolution. It becomes a visual roadmap and a way to identify places I’ve gone wrong. Once we’d written several drafts, Max and I realized we needed to do the same. We diagrammed our roadmap or story arc and began rewriting.

From the beginning it was clear to us that our story started when Max had his first episode and was diagnosed with Bipolar I. However, our first drafts were narrations of one painful episode after another. Though each episode was different, the narration became wearing and numbing. It was too much. We realized we shouldn’t be including scenes just because they happened. So we cut, using only the episodes that moved the narration forward, revealing something new about our situation, the illness, about Max, about me. So much good material ended up on the cutting room floor. Most writers know how hard it is to ax what you consider perfect prose, a gripping scene, or an event you want to share, but if the narration didn’t add to the forward movement of the story, we took it out. Those scenes and bits of prose are tucked away in our computers. Perhaps one of them will someday make a great short story.

Finding the right place to end was just as challenging. It was then that we again turned to the story arc, knowing that we needed to find a climax and resolution. So we cut the narration of Max’s last episode. (We know well that we can never really call an episode “last” anyway because bipolar doesn’t go away.) Instead we ended with the episode that was in many ways the worst—a culmination of all the other episodes and Max’s closest brush with death. The resolution followed in the final chapters, the summing of the years of crisis and fear, the coming to terms with the illness, the recognition that Max’s illness is forever but that recovery is possible.

In many ways, I think we approached the memoir the only way Max and I could. When we began, we were trying to make sense of the years of struggle and confusion. Writing everything out helped. We weren’t at all sure where we were going until we got there. We really didn’t know what we were trying to accomplish, what was ultimately important to us, until we’d been mired in the material for a couple of years. Yes, years. Only then did things start to take shape.

Once we reached some solid ground, we wrote and rewrote, every draft tighter and more vivid than the last—eliminating clichés, generalizations, and abstraction, seeking the real words, the ones that drew a clear picture and told an honest story. We wanted those who read the book to put themselves in our shoes. We wanted them to understand what those with mental illness and their families go through.

By the time we’d come to the end, we knew we’d succeeded in telling the story we wanted to tell and could ultimately answer the questions I list for you to consider as you write your own memoir. But keep in mind; these are only tools to help you along the way as you develop your story. You have to be willing to rethink, reshape, and rewrite. You have to “see what you write before to know what you mean.”

Eight Questions to Consider as You Draft Your Memoir:

What is the story/situation? What is the life-changing event in your life?

What is the time period?

What is the conflict? (with yourself, with another, with a situation)

What is the initiating event?

What are the specific events and obstacles. At some point, step back and evaluate, include what is important and meaningful to the story (not everything that is meaningful to you.) Each event should be included because it advances story.

What is the turning point—final crisis?

What is the ending event? What is the resolution?

What do you want your readers to take away? (sharing wisdom, helping others going through it, healing, understanding yourself.)

Suggested Reading about Story Arc:

Screenplay, Syd Field (a screen writer explains structure in this short, concise, and clear book that includes diagrams) for writers of Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces)

The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, Christopher Vogler (a rendering for writers of Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting, Robert McKee (another screen writer’s in- depth book about how to write a story—down to the last

sentence.)

May 19, 2013

Bipolar Disorder–From Diagnosis to Recovery

Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar Illness

(Available here)

The day I realized my son, Max, had bipolar disorder, he’d called at 5 a.m. and told me to turn on the television. The truth was in the programming, he said. A new world was emerging. Holding out hope that the world really had shifted and not Max, I turned on the TV. But I knew the idyllic family I discovered on a Leave it to Beaver rerun didn’t reflected the new world of which Max had spoken. Max was diagnosed with Bipolar I that afternoon. He was twenty and a junior at a small liberal arts college in the cornfields of Iowa.

Since that morning, I’ve spent hours on psychiatric units from Colorado to Philadelphia because I’ve never wanted Max to feel alone in his illness. I listened as words tumbled from my son’s manic being. I dug his ruined poems fro m the trash where he’d tossed them in disgust. For me, Max’s verse was a reminder of his promise and one of many souvenirs through the maze of bipolar disorder. I’ve sat with other patients too, whom I’ve come to treasure like characters in a novel—a patient who asked me to his senior prom and called me Ruthie; a tattoo-covered drug dealer who depended on the cinnamon gum he knew I always carried in my pocket.

m the trash where he’d tossed them in disgust. For me, Max’s verse was a reminder of his promise and one of many souvenirs through the maze of bipolar disorder. I’ve sat with other patients too, whom I’ve come to treasure like characters in a novel—a patient who asked me to his senior prom and called me Ruthie; a tattoo-covered drug dealer who depended on the cinnamon gum he knew I always carried in my pocket.

And Max? He wandered the streets, always seeking something intangible and unknown. Of his illness he writes, “She was the promise, the one that could never be made good. But a promise so great that its very mirage crippled even the strongest of wills.” He returned to school the next semester, embarrassed by his failed prophesies and discomforted by the suspicious glance of friends. And of depression he writes: “Quick was the rant of suicidal ideation to snuff out any lingering hope for a normal life. The question of how to end it turned into minute-by-minute thinking. I awoke disgraced, morning, noon, or night, Monday or Friday, the same lingering taste at the tip of my dry tongue, like a name whose thought made my mind blank.”

In Walks on the Margins, A Story of Bipolar Illness, Max and I write about what it means to suffer from mental  illness. Though reliving the years of confusion and fear was difficult, the writing helped us make sense of the chaos. We’ve tried to tell an honest though often painful story that ends with the understanding that mental illness is for life but that redemption and recovery are possible. We hope that others with mental illness and their families will find comfort in the book and will realize they aren’t as alone as they may think. We also hope that by putting a face on mental illness, we have succeeded in breaking down the barriers of stigma and made human and understandable an illness that so many fear.

illness. Though reliving the years of confusion and fear was difficult, the writing helped us make sense of the chaos. We’ve tried to tell an honest though often painful story that ends with the understanding that mental illness is for life but that redemption and recovery are possible. We hope that others with mental illness and their families will find comfort in the book and will realize they aren’t as alone as they may think. We also hope that by putting a face on mental illness, we have succeeded in breaking down the barriers of stigma and made human and understandable an illness that so many fear.

Walks on the Margins isn’t just our story. It’s the story of thousands of others who have mental illness and of the families who love them.

The book is available on Amazon.

A Mom & Son Tell Their Story of Bipolar Disorder

Walks on the Margins: A Story of Bipolar Illness

(Available at: (http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00C8WLXMW/)

The day I realized my son, Max, had bipolar disorder, he’d called at 5 a.m. and told me to turn on the television. The truth was in the programming, he said. A new world was emerging. Holding out hope that the world really had shifted and not Max, I turned on the TV. But I knew the idyllic family I discovered on a Leave it to Beaver rerun didn’t reflected the new world of which Max had spoken. Max was diagnosed with Bipolar I that afternoon. He was twenty and a junior at a small liberal arts college in the cornfields of Iowa.

Since that morning, I’ve spent hours on psychiatric units from Colorado to Philadelphia because I’ve never wanted Max to feel alone in his illness. I listened as words tumbled from my son’s manic being. I dug his ruined poems fro m the trash where he’d tossed them in disgust. For me, Max’s verse was a reminder of his promise and one of many souvenirs through the maze of bipolar disorder. I’ve sat with other patients too, whom I’ve come to treasure like characters in a novel—a patient who asked me to his senior prom and called me Ruthie; a tattoo-covered drug dealer who depended on the cinnamon gum he knew I always carried in my pocket.

m the trash where he’d tossed them in disgust. For me, Max’s verse was a reminder of his promise and one of many souvenirs through the maze of bipolar disorder. I’ve sat with other patients too, whom I’ve come to treasure like characters in a novel—a patient who asked me to his senior prom and called me Ruthie; a tattoo-covered drug dealer who depended on the cinnamon gum he knew I always carried in my pocket.

And Max? He wandered the streets, always seeking something intangible and unknown. Of his illness he writes, “She was the promise, the one that could never be made good. But a promise so great that its very mirage crippled even the strongest of wills.” He returned to school the next semester, embarrassed by his failed prophesies and discomforted by the suspicious glance of friends. And of depression he writes: “Quick was the rant of suicidal ideation to snuff out any lingering hope for a normal life. The question of how to end it turned into minute-by-minute thinking. I awoke disgraced, morning, noon, or night, Monday or Friday, the same lingering taste at the tip of my dry tongue, like a name whose thought made my mind blank.”

In Walks on the Margins, A Story of Bipolar Illness, Max and I write about what it means to suffer from mental  illness. Though reliving the years of confusion and fear was difficult, the writing helped us make sense of the chaos. We’ve tried to tell an honest though often painful story that ends with the understanding that mental illness is for life but that redemption and recovery are possible. We hope that others with mental illness and their families will find comfort in the book and will realize they aren’t as alone as they may think. We also hope that by putting a face on mental illness, we have succeeded in breaking down the barriers of stigma and made human and understandable an illness that so many fear.

illness. Though reliving the years of confusion and fear was difficult, the writing helped us make sense of the chaos. We’ve tried to tell an honest though often painful story that ends with the understanding that mental illness is for life but that redemption and recovery are possible. We hope that others with mental illness and their families will find comfort in the book and will realize they aren’t as alone as they may think. We also hope that by putting a face on mental illness, we have succeeded in breaking down the barriers of stigma and made human and understandable an illness that so many fear.

Walks on the Margins isn’t just our story. It’s the story of thousands of others who have mental illness and of the families who love them.

The book is available on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00C8WLXMW/

May 15, 2013

If Not You, Who? If Not Now, When? Advocate for Mental Health

Three Ways to Become a Mental Health A dvocate

by Steve Curran

Mental illness is in the news a lot these days and most of the time it is not good. Usually a tragic event or some celebrity making horrible headlines adds to the already negative view that most people have about those with mental illness, including those of us who are diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

I decided early in my recovery that it was up to me to advocate and create awareness about my disease. I was nervous at first, but the more I talked with others the more comfortable I felt. I started off with my family and then moved on to friends. I first talked about living with bipolar disorder to a complete stranger in my doctor’s office while waiting for my appointment. I took a deep breath, caught her eye, and asked if I could share my story. I stumbled once or twice, but I did pretty well and she was touched. I was now a Mental Health Advocate!

Three ways to create positive awareness about Bipolar Disorder:

Talk to others! Think of a couple of points you would like folks to know about living with bipolar disorder (your history, depression, wellness, etc.). Most people are not familiar with bipolar illness and will not only be interested, but will also begin to better understand mental illness.

Write about your bipolar journey. Sit down and put together a page or two about your history. Submit it to your local paper as an article or Letter to the Editor. You can also find many outlets for your story on the internet. If you are a bit shy or if you worry about the stigma, you can do this anonymously.

Volunteer at The National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) and the (DBSA), two great national organizations that have local chapters across the country. They will appreciate the help and it costs nothing to donate your time!

Putting a face on our disease and letting people know what living with bipolar disorder is all about will have a huge impact on others. Not only will they be learning about important health issue, but you will become even more empowered to advocate. If you are like me, you will also find it very therapeutic.

You and I must be involved in efforts to change public perceptions of mental illness. We know the pain of bipolar and the contentment of learning to live successfully with our disease. We really are bipolar disorder experts and are extremely qualified to speak on this subject.

If not you, who? If not now, when?

About the Steve Curran: Following a suicide attempt in 2006, Steve Curran made it his mission to bring awareness about the disease of Depression. Curran, a Mental Health Advocate and suicide survivor, is sharing his inspiring story of living with mental illness. As a professional speaker and blogger, Curran has touched thousands of lives by offering a unique and intimate perspective on depression. From a suicide attempt and numerous hospitalizations to organizing the triumphant Walk To Washington depression awareness campaign, Curran is on a mission to change the public’s perception of depression and advocate for victims of the disease. The good news is that Depression, even in the most severe cases, is treatable. Curran is proof of that and wants to give hope to others struggling with depression. Visit Depression Awareness at http://depressionawareness.org/

*** I’m grateful to Steve Curran for participating as a guest blogger, for telling his story and for contributing to the conversation about mental health issues.

If Not You, Who? If Not Now, When?

Three Ways to Become a Mental Health A dvocate

by Steve Curran

Mental illness is in the news a lot these days and most of the time it is not good. Usually a tragic event or some celebrity making horrible headlines adds to the already negative view that most people have about those with mental illness, including those of us who are diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

I decided early in my recovery that it was up to me to advocate and create awareness about my disease. I was nervous at first, but the more I talked with others the more comfortable I felt. I started off with my family and then moved on to friends. I first talked about living with bipolar disorder to a complete stranger in my doctor’s office while waiting for my appointment. I took a deep breath, caught her eye, and asked if I could share my story. I stumbled once or twice, but I did pretty well and she was touched. I was now a Mental Health Advocate!

Three ways to create positive awareness about Bipolar Disorder:

Talk to others! Think of a couple of points you would like folks to know about living with bipolar disorder (your history, depression, wellness, etc.). Most people are not familiar with bipolar illness and will not only be interested, but will also begin to better understand mental illness.

Write about your bipolar journey. Sit down and put together a page or two about your history. Submit it to your local paper as an article or Letter to the Editor. You can also find many outlets for your story on the internet. If you are a bit shy or if you worry about the stigma, you can do this anonymously.

Volunteer at The National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) and the (DBSA), two great national organizations that have local chapters across the country. They will appreciate the help and it costs nothing to donate your time!

Putting a face on our disease and letting people know what living with bipolar disorder is all about will have a huge impact on others. Not only will they be learning about important health issue, but you will become even more empowered to advocate. If you are like me, you will also find it very therapeutic.

You and I must be involved in efforts to change public perceptions of mental illness. We know the pain of bipolar and the contentment of learning to live successfully with our disease. We really are bipolar disorder experts and are extremely qualified to speak on this subject.

If not you, who? If not now, when?

About the Steve Curran: Following a suicide attempt in 2006, Steve Curran made it his mission to bring awareness about the disease of Depression. Curran, a Mental Health Advocate and suicide survivor, is sharing his inspiring story of living with mental illness. As a professional speaker and blogger, Curran has touched thousands of lives by offering a unique and intimate perspective on depression. From a suicide attempt and numerous hospitalizations to organizing the triumphant Walk To Washington depression awareness campaign, Curran is on a mission to change the public’s perception of depression and advocate for victims of the disease. The good news is that Depression, even in the most severe cases, is treatable. Curran is proof of that and wants to give hope to others struggling with depression. Visit Depression Awareness at http://depressionawareness.org/

*** I’m grateful to Steve Curran for participating as a guest blogger, for telling his story and for contributing to the conversation about mental health issues.