Jamie Malanowski's Blog, page 13

June 30, 2013

BROADWAY BABY

I haven’t been to the theater in a long time, but thanks to a secret benefactor, I was able to see two shows this week, both star vehicles. The first, I’ll Eat You Last, was an amusing trifle starring Bette Midler as the once legendary Hollywood agent Sue Mengers. As a decades-long fan of Midler and her flamboymant, brassy, over-the-top, vulgar (But true! and generous! and kind!) brilliance, it was fun to see her play the flamboyant, brassy, over-the-top, vulgar, true, generous, kind and brilliant Mengers. About eighty minutes long, with lots of smutty punchlines, a few good anecdotes, and really expensive tickets, it’s almost certainly making everybody concerned fistsful of dollars.

I haven’t been to the theater in a long time, but thanks to a secret benefactor, I was able to see two shows this week, both star vehicles. The first, I’ll Eat You Last, was an amusing trifle starring Bette Midler as the once legendary Hollywood agent Sue Mengers. As a decades-long fan of Midler and her flamboymant, brassy, over-the-top, vulgar (But true! and generous! and kind!) brilliance, it was fun to see her play the flamboyant, brassy, over-the-top, vulgar, true, generous, kind and brilliant Mengers. About eighty minutes long, with lots of smutty punchlines, a few good anecdotes, and really expensive tickets, it’s almost certainly making everybody concerned fistsful of dollars.

The second play, Lucky Guy, starred Tom Hanks as the  newspaper columnist Mike McAlary. I expected to hate it, since it was by Nora Ephron, and I find most of what Ephron has written for the screen to be cloyingly sentimental, with performances that suck you in with a kind of dazzle and stories that ultimately leave you feeling like you’ve read a Hallmark card. And do you know what? This show was highly sentimental, and I . . .kind of. . . liked it. And it was cloying, just the same. But three things really worked. First, the performances were good: Hanks, Peter Gehrity, Maura Tierney, Courtney B. Vance and especially Chrstopher McDonald. Second, Ephron very adroitly dovetailed the rise and fall and ultimate death of Mike McAlary with the rise and heyday and fall and soon-to-be death of tabloid newspapers, and it was well done–very well perceived. Second, George Wolfe‘s energetic, flashy staging really worked for me. The play was odd–lots of loud, vulgar language, lots of speed, lots of action. In many, many scenes, actors broke the fourth wall and speaking loudly, talked directly to the audience, narrating the story. After a while, I got it–the actors were playing newspapermen, and they were acting like the papers they wrote for, shouting at you from the newsstand, shouting to get your attention, shouting to make you hear the story they had to tell. The play was very much a love letter to a way of life that has all but disappeared. Maybe you had to be in journalism to fully commit to the play, to overlook its faults. But I was in journalism. I read those papers. And I liked the play.

newspaper columnist Mike McAlary. I expected to hate it, since it was by Nora Ephron, and I find most of what Ephron has written for the screen to be cloyingly sentimental, with performances that suck you in with a kind of dazzle and stories that ultimately leave you feeling like you’ve read a Hallmark card. And do you know what? This show was highly sentimental, and I . . .kind of. . . liked it. And it was cloying, just the same. But three things really worked. First, the performances were good: Hanks, Peter Gehrity, Maura Tierney, Courtney B. Vance and especially Chrstopher McDonald. Second, Ephron very adroitly dovetailed the rise and fall and ultimate death of Mike McAlary with the rise and heyday and fall and soon-to-be death of tabloid newspapers, and it was well done–very well perceived. Second, George Wolfe‘s energetic, flashy staging really worked for me. The play was odd–lots of loud, vulgar language, lots of speed, lots of action. In many, many scenes, actors broke the fourth wall and speaking loudly, talked directly to the audience, narrating the story. After a while, I got it–the actors were playing newspapermen, and they were acting like the papers they wrote for, shouting at you from the newsstand, shouting to get your attention, shouting to make you hear the story they had to tell. The play was very much a love letter to a way of life that has all but disappeared. Maybe you had to be in journalism to fully commit to the play, to overlook its faults. But I was in journalism. I read those papers. And I liked the play.

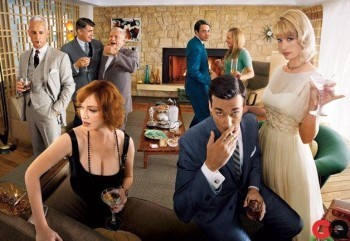

MAD AT MAD MEN

As an early and excited fan of Mad Men (Okay, I realize that this doesn’t make me the first man on the moon, but I was there), it saddens me to say that I was pretty disappointed in this past season. I know others disagree–Troy Patterson in Slate called it the show’s best season ever–but I felt let down.

As an early and excited fan of Mad Men (Okay, I realize that this doesn’t make me the first man on the moon, but I was there), it saddens me to say that I was pretty disappointed in this past season. I know others disagree–Troy Patterson in Slate called it the show’s best season ever–but I felt let down.

When Mad Men debuted, among the many things that was so brilliant the show was who the show was about–though set in 1960, it was about us. It was about us in two ways: first, it showed the birth of what may be called `our era’–the birth of a fully integrated America, the birth of women in the work force, the birth of a sexually freer country, the birth of more psychologically aware country. Second, it was about us, the people who were living in the first years of the 21st century, the years when the good days were ending and a crack-up loomed over the horizon. The show, of course, was about other things, notably the tortured soul of Don Draper. But lets face it: there’s only so much tortured soul crap we take from our friends and loved ones, and I believe I speak for most of us when say that my tolerance for it among my favorite fictional characters is even less. Megan Draper may have to put up with Don coming home ever night half in the bag, but I don’t, not unless he and Roger Sterling and Freddie Rumson have gone to an after-hours gambling joint and punched Jimmy Barrett in the jaw first. That’s the Don I like, the Don who, however deplorable, is always able to out wit the Ducks on the world.

In this season, set in 1968, Matthew Weiner and his creative team treated all these imperatives with a lot of literalness. We followed Don into a season-long descent into alienation, witnessing a sadistic relationshipo with his mistress, general meanness to his colleagues, neglect of his his wife and children (what’s new?) and a trip to the drunk tank, although in the final episode we were given a flickering indication that a turnaround might be in order. We also experienced the turbulent events of 1968 with at once a surface literalness (seeing the riots on TV) and a theatrical surrealism, like the elderly black woman thief or the Chevy account as Mad Men‘s Vietnam (see Slate‘s very smart deconstruction). This is an exercise in not very entertaining intellectual masturbation, a dog whistle that went over most of the audience’s head. Weiner, moreover, began to repeat himself, with another mysterious liar in Bob Benson and another Pete Campbell parent being lost in transit. Would it have been a challenge for one of the characters to have been caught up in street turmoil at Columbia or the Chicago convention? Almost certainly–you see things like that all time in inferior programs so frequently that it becomes a cliche. But presented with the challenge to elevate this moment, the writers punted. The reality of the era was played for decoration, for surfaces. Abe’s radicalism was revealed to be careerism, a bourgois boomer wrapped in a lefty taco. Ginzberg and Rizzo and Megan were shown to be liberals with no bottom. Megan spouted anit-war bromides, but never did anything. The attitudes were a superficial as the buttons pinned to Glenn’s pea coat. None of them went to a rally, none of them went to a meeting, none of them did any pro bono work, none of them marched. But some of those people would have. During the whole year, Betty was the only who actually saw something face to face. This was a huge swing and a miss for what had been the Mantle of TV shows.

By the way, what ever happened to Mad Men‘s Republicans? I was delighted to see that in the final episode, the bar where Don met the evangelist had for some reason two political posters hanging on the wall: a vintage Nixon’s the One poster, and one for Roy Goodman, who was the Republcan state senator for the Upper East Side of Manhattan from 1969 to 2002, a liberal Rockefeller Republican whose kind we just don’t see anymore. I thought that one of the most original Mad Men insights was that Cooper and Sterling were Republicans, that the firm worked for Nixon in 1960, that Bert Cooper was part of old money, board-sitting Manhattan Republican establishment. The advent of Henry Francis kept this going. but as the show lost interest in Betty it lost interest in Henry, and a whole fruitful dramatic path was back-burnered. Remember, we think of the sixties as a period when things went to hell, but they didn’t go to hell for everybody: Nixon won, and he won with the help of Haldeman and Ehrlihman and Roger Ailes and Ron Ziegler, all of them products of the Mad Men milieu. I’m sorry Weiner has let this story line slacken. I had hoped that by the end of the final season, as 1969 drew to a close, we would be seeing Pete Campbell taking the first steps that would eventually lead him to his indictment in the Watergate conspiracy.

June 25, 2013

MISUNDERSTANDING THE CIVIL WAR

Tony Horwitz has written an excellent article in The Atlantic called “150 Years of Misunderstanding the Civil War.” Horwitz, author of the very pereptive A Confederate in the Attic, makes the point that point that most Americans have a thin but generally positive view of the war, a post-WW II, post-civil rights era assessment that holds that because the war ended slavery, an `all’s well that ends well’ view of the conflict should pertain. “We’ve decided the Civil War is a ‘good war’ because it destroyed slavery,” Horwitz quotes historian Fitzhugh Brundage. “I think it’s an indictment of 19th century Americans that they had to slaughter each other to do that.” Horwitz says that this view was also held “by an earlier generation of historians known as revisionists. From the 1920s to 40s, they argued that the war was not an inevitable clash over irreconcilable issues. Rather, it was a “needless” bloodbath, the fault of `blundering’ statesmen and `pious cranks,’ mainly abolitionists. Some revisionists, haunted by World War I, cast all war as irrational, even `psychopathic”’ Horwitz points to a new generation of skeptics, including David Goldfield, author of America Aflame, who says that the war was “America’s greatest failure.’ Goldfield accuses politicians, extremists, and evangelical Christians for polarizing the nation to the point where compromise or reasoned debate became impossible.

Tony Horwitz has written an excellent article in The Atlantic called “150 Years of Misunderstanding the Civil War.” Horwitz, author of the very pereptive A Confederate in the Attic, makes the point that point that most Americans have a thin but generally positive view of the war, a post-WW II, post-civil rights era assessment that holds that because the war ended slavery, an `all’s well that ends well’ view of the conflict should pertain. “We’ve decided the Civil War is a ‘good war’ because it destroyed slavery,” Horwitz quotes historian Fitzhugh Brundage. “I think it’s an indictment of 19th century Americans that they had to slaughter each other to do that.” Horwitz says that this view was also held “by an earlier generation of historians known as revisionists. From the 1920s to 40s, they argued that the war was not an inevitable clash over irreconcilable issues. Rather, it was a “needless” bloodbath, the fault of `blundering’ statesmen and `pious cranks,’ mainly abolitionists. Some revisionists, haunted by World War I, cast all war as irrational, even `psychopathic”’ Horwitz points to a new generation of skeptics, including David Goldfield, author of America Aflame, who says that the war was “America’s greatest failure.’ Goldfield accuses politicians, extremists, and evangelical Christians for polarizing the nation to the point where compromise or reasoned debate became impossible.

Writes Horwitz, “Unlike the revisionists of old, Goldfield sees slavery as the bedrock of the Southern cause and abolition as the war’s great achievement. But he argues that white supremacy was so entrenched, North and South, that war and Reconstruction could never deliver true racial justice to freed slaves, who soon became subject to economic peonage, Black Codes, Jim Crow, and rampant lynching. Nor did the war knit the nation back together. Instead, the South became a stagnant backwater, a resentful region that lagged and resisted the nation’s progress. It would take a century and the Civil Rights struggle for blacks to achieve legal equality, and for the South to emerge from poverty and isolation. “Emancipation and reunion, the two great results of this war, were badly compromised,” Goldfield says. Given these equivocal gains, and the immense toll in blood and treasure, he asks: “Was the war worth it? No.”

I have often wondered if the war was worth it. More than 700,000 dead (plus tens of thousands more wounded) versus the prolonged enslavement of 4 million people? It is some kind of cosmic ethical math problem that only God could solve, and God, when he had the chance, picked war. Imagine if the the north had allowed the south the secede. I think the north would have embarked on an effort to acquire Canada, either through war (the United States and Great Britain nearly went to war over Canadian issues in 1862) or through acquisition (it seems there was genuine interest on the part of Britain to sell the place. Add Alaska in 1867, and the United States of North America looks mighty strong. I don’t know about the Confederate states. There would be expeditions to conquer land in Central America, Mexico and Cuba; not clear that they would succeed. French interest in Mexico would create problems in Texas, Louisiana and maybe Florida, and there would be continued problems in west Texas with the Comanches, as S.C. Gwynne showed in his wonderful Empire of the Summer Moon. Booth countries would have turmoil along their mutual border, as malcontents on both sides would have a place to look longingly towards. The south would have more problems: slaves would now have some place to escape to, and there would be no Fugitive Slave Law to require their return.

Would slavery have ended? I like to think it would have, and before the turn of the century. First, slavery was dying out in the upper south. Second, the war interrupted a nascent southern populist movement

that might have grown into a force. Third, might there have been a reform movement started by women; whenever I read Mary Chesnut‘s observations, I see a woman with a sharpening sense of the hypocrisy and injustice and cruelty created by slavery, and she doesn’t like it. Finally, I suspect young southerners would have seen the dynamisn in the north, and would have rebelled at the recondite practices of their parents. Progress may have been more possible if the south had not lost a war. Solutions may have been reached more swiftly–and might have been more easily accepted–if pride and disgrace weren’t involved.

June 23, 2013

JAMES GANDOLFINI, 1961-2013

The question of whether James Gandolfini was the greatest actor of his era will be settled sometime in the future. Commentators will have to decide whether an 86 hour performance as one character (plus 25 or so stellar supporting performances) required more of an actor, and delivered more from an actor, than did, say, twenty or so bravura film performances by Daniel Day Lewis.

The question of whether James Gandolfini was the greatest actor of his era will be settled sometime in the future. Commentators will have to decide whether an 86 hour performance as one character (plus 25 or so stellar supporting performances) required more of an actor, and delivered more from an actor, than did, say, twenty or so bravura film performances by Daniel Day Lewis.

Almost impossible to compare, right? Almost ludicrous to contemplate. Yet if critics and commentators do in fact, try to make that comparison, it will be because Gandolfini, and David Chase, along with the rest of the talents associated with The Sopranos, seized with their brilliance the cultural ground that cinema was abandoning like they were owners of residential property at Love Canal.

Once movies slew the novel in the sixties, film was considered the most culturally significant art form. Part of it had to do with the iconic power of the stars, part with the way fans and the media treated film, part with the depth and ambitions of the film makers, with what they were trying to say. There was a time when a film could influence the culture for two years. It would open in a downtown movie house and spread slowly throughout the country; if it was a hit, it would run in cities for months, and in parts of the country, people would be waiting for close to two years to see a major picture. Crowning that influence were the Oscars, honors that could cement the stature of a film or a performer for decades. And in that way, generations would contemplate the meaning of The Godfather, Lawrence of Arabia, Casablanca, On the Waterfront, Nashville, Chinatown, and so on.

Now movies come and go so fast they barely register. They open wide and even successful films get moved out fast. The significance of the Oscar has diminished in a crowd of other award shows. But with ten or thirteen week runs (along with in-week repeats and off-season reruns), with the close analysis some series receive and the big build-ups to new seasons, and most importantly, with their greater ambitions and more serious content, it is TV shows like Mad Men or Game of Thrones or Girls that dominate the culture. At a conference in Hollywood ten days ago, Steven Spielberg predicted a coming “implosion” in the film industry, after which there will be price variances at movie theaters, where “you’re gonna have to pay $25 for the next Iron Man, you’re probably only going to have to pay $7 to see Lincoln.” He also said that Lincoln came “this close” to being an HBO movie instead of a theatrical release. Speaking on the same panel, George Lucas predicted that film exhibition would morph into a Broadway play model, whereby fewer movies are released, they stay in theaters for a year and ticket prices are much higher. His prediction prompted Spielberg to recall that his 1982 film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial stayed in theaters for a year and four months. Lucas called cable television “much more adventurous” than film nowadays.

Why is this happening? Technological changes, demographic changes, audience preferences—huge movements. But I believe it wouldn’t be happening now, and in the way it has been happening, if The Sopranos hadn’t been so damn good. And it was Chase’s writing and vision, and Gandolfini’s acting, that made it happen.

The Sopranos was The Death of a Salesman of our era: a vision of the way we lived and worked and the costs involved. At first it played as a comedy with a twisted undercurrent of violence; the very simple decision to play the mobster as a suburban family man created the comic framework that the show never shed. This must have horrified Chase, who each season thereafter made Tony an uglier, more violent, more selfish, more controlling and less in control character. But Chase continued to allow Tony elements of humor and especially humanity, and Gandolfini squeezed the compassion out of each opportunity. “AJ, you’re a good guy,’’ says a frustrated Tony to his son in one late episode, and breaking into Gandolfini’s delivery of that line was all of Tony’s anguished, desperate suspicion that AJ was in no way a good guy, not a good citizen in possession of a compassionate heart, and not even a good criminal, a stand-up guy in possession of the nominal capabilities of that profession. You felt sympathy for Tony in that instant, as in so many instants, when Gandolfini expressed a universal human emotion, in this case a father’s terror that his kid might be a ne’er-do-well.

The question of whether James Gandolfini was the greatest actor of his era will be settled sometime in the future when commentators decide whether an 86 hour performance as one character (plus 25 or so stellar supporting performances) required more of an actor, and delivered more from an actor, than did, say, twenty or so bravura film performance by Daniel Day Lewis.

Almost impossible to compare, right? Almost ludicrous to contemplate. Yet if critics and commentators do in fact, try to make that comparison, it will be because Gandolfini, and David Chase, and the rest of the talents associated with The Sopranos, seized with their brilliance the cultural ground that cinema was abandoning like they were owners of residential property at Love Canal.

Once movies slew the novel in the sixties, film was considered the most culturally significant art form. Part of it had to do with the iconic power of the stars, part with the way fans and the media treated film, part with the depth and ambitions of the film makers, with what they were trying to say. There was a time when a film could influence the culture for two years. It would open in a downtown movie house and spread slowly throughout the country; if it was a hit, it would run in cities for months, and in parts of the country, people would be waiting for close to two years to see a major picture. Crowning that influence were the Oscars, honors that could cement the stature of a film or a performer for decades. And in that way, generations would contemplate the meaning of The Godfather, Lawrence of Arabia, Casablanca, On the Waterfront, Chinatown, and so on.

Now movies come and go so fast they barely register. They open wide and even successful films get moved out fast. The significance of the Oscar has diminished in a crowd of other award shows. But with ten or thirteen week runs (along with in-week repeats and off-season reruns), with the close analysis some series receive and the big build-ups to new seasons, and most importantly, with their greater ambitions and more serious content, it is TV shows like Mad Men or Game of Thrones that dominate the culture. At a conference in Hollywood ten days ago, Steven Spielberg predicted a coming “implosion” in the film industry, after which there will be price variances at movie theaters, where “you’re gonna have to pay $25 for the next Iron Man, you’re probably only going to have to pay $7 to see Lincoln.” He also said that Lincoln came “this close” to being an HBO movie instead of a theatrical release. Speaking on the same panel, George Lucas predicted that film exhibition would morph into a Broadway play model, whereby fewer movies are released, they stay in theaters for a year and ticket prices are much higher. His prediction prompted Spielberg to recall that his 1982 film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial stayed in theaters for a year and four months. Lucas called cable television “much more adventurous” than film nowadays.

Why is this happening? Technological changes, demographic changes, audience preferences—huge movements. But I believe it wouldn’t be happening now, and in the way it has been happening, if The Sopranos hadn’t been so damn good. And it was Chase’s writing and vision, and Gandolfini’s acting, that made it happen.

The Sopranos was The Death of a Salesman of our era: a vision of the way we lived and worked and the costs involved. At first it played as a comedy with a twisted undercurrent of violence; the very simple decision to play the mobster as a suburban family man created the comic framework. This must have horrified Chase, who each season thereafter made Tony an uglier, more violent, more selfish, more controlling and less in control character. But Chase continued to allow Tony elements of humanity, and Gandolfini squeezed the compassion out of each opportunity. “AJ, you’re a good guy,’’ says a frustrated Tony to his son in one late episode, and breaking into Gandolfini’s delivery of that line was all of Tony’s anguished suspicion that AJ was in no way a good guy, not a good citizen in possession of a compassionate heart, and not even a good criminal, a stand-up guy in possession of the nominal capabilities of that profession. You felt sympathy for Tony in that instant, as in so many instants, when Gandolfini expressed a universal human emotion, in this case a father’s terror that his kid might be a ne’er-do-well.

Gandolfini possessed an astonishingly expressive face, and it was constantly in motion. (It’s amazing what he did with his voice, too; it’s astonishing to realize that Tony’s voice was not Gandolfini’s natural voice, that Gandolfini pitched it higher and altered his natural cadences and altered his accent for the part.) In my favorite episode, the 12th of season 2, Gandolfini’s gifts and skills are on peacock display. Following the scene in which Janice shoots Richie Aprile, Tony registers fear, caution, shock, control, authority, fury, sarcasm, love, affection, exasperation—all in a handful of minutes. He calms his sister, he commands his men, he yells at his mother, he mocks his sister, and he opens himself, cautiously, to his wife. It’s just wonderful. And it is one of, I don’t know, ten thousand sequences that mark Gandolfini’s excellence, in The Sopranos and other pieces. (The wonderful In the Loop is Peter Capaldi‘s movie, but Gandolfini holds his own in every scene he’s in.)

The first episode of The Sopranos aired on January 10, 1999. I was working for Entertainment Weekly, and Ginny and the girls met me in Manhattan. Somehow we ended up at a restaurant called Mayrose, on Broadway near the Flatiron building. We were there early, maybe six o’clock., and the place was nearly empty, although by himself, right in the front, was a man I recognized as James Gandolfini. I almost never bother celebrities, but he was right there, practically underfoot as we waited to be seated, so I put out my hand and congratulated him, and wished him and show great success. I’m glad I did that. It was one of a tiny number of times in my life that I have shaken the hand of genius.

June 19, 2013

Why Fort Hood Needs a New Name

This piece first ran in The Dallas Morning News on June 16, 2013.

Fort Hood is the Army installation in Killeen, halfway between Austin and Waco. The base opened in January 1942, serving as a training center for soldiers joining artillery and anti-tank units. Today, it’s the Army’s largest active-duty armored post, a base where approximately 41,000 soldiers work.

It is also one of 10 functioning Army bases named for a Confederate general. There used to be many more. During World War I and World War II, the War Department opened a large number of new bases, many in the South, where the warmer weather permitted more time for training. Bases were customarily named after military heroes, and although ultimate responsibility for the choice rested with the War Department, civilian input was allowed and political pressure inevitable.

In the 1940s, sensitivities about the Civil War still ran high. Many people still had a personal connection with someone who had served in the war. There remained a need to bind the nation together more closely, and so no one really challenged the appropriateness of naming U.S. Army bases after generals who had led troops against the U.S. Army in battle. “We’re all Americans,” was the line.

Consequently, in Virginia, we still have Fort Lee, named for Robert E. Lee, a man universally admired for his personal integrity and military skills. Yet, as historian Ken Burns has noted, he was responsible for the deaths of more U.S. Army soldiers than Hitler and Tojo. Also in Virginia is Fort A.P. Hill, named for an officer whose peerless ferocity was increasingly undermined by the frequent periods of incapacitation he suffered from a syphilis infection; and Fort Pickett, named in honor of Gen. George Pickett, whose division was decimated at Gettysburg. Pickett was accused of war crimes for ordering the execution of 22 Union prisoners; his defense was that they had all previously deserted from the Confederate army. In the end, he was not charged.

In Georgia, there is Fort Benning and Fort Gordon. Henry Benning was a state Supreme Court justice who became one of Lee’s more effective subordinates. Prior to the war, this fervent secessionist inflamed fears of abolition, which he predicted would inevitably lead to black governors, juries, legislatures and more. “Is it to be supposed that the white race will stand for that?” Benning said in a speech in February 1861. “We will be overpowered, and our men will be compelled to wander like vagabonds all over the Earth, and as for our women, the horrors of their state we cannot contemplate in imagination.”

Like Benning, John B. Gordon was another of Lee’s most dependable commanders. Before the war, Gordon sought secession as the first step to creating a slaveholding empire. Speaking at Oglethorpe University in June 1860, Gordon told the students that if they resisted threats to their “constitutional liberty” — i.e. the right to own slaves — then “the day is not far distant when the Southern flag shall be omnipotent from the Gulf of Mexico to the coast of Delaware; when Cuba will be ours, when the Western breeze shall kiss our flag, as it floats in triumph from the gilded turret of Mexico’s capital; when the well-clad, well-fed Southern Christian slave shall beat his tambourine and banjo, amid the orange-bowered groves of Central America; and when a pro-slavery legislature shall meet in council at Montezuma.” After the war, he headed the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia. He “may not have condoned the violence employed by Klan members,” says his biographer Ralph Lowell Eckert, “but he did not question or oppose it when he felt it was justified.”

John Bell Hood was different from these men: not as good a general as Lee, but better than Pickett and Hill. He was certainly better than the irascible, incompetent Braxton Bragg (Fort Bragg, N.C.) and the indecisive, frequently disastrous Leonidas Polk (Fort Polk, La.), a bishop turned general who personally owned several hundred slaves.

Hood was not a fire-eating secessionist like Benning or Gordon, but he was quite clear-minded about the cause he had joined. (“Regardless of all other causes of difference,” he said in a speech after the war, “slavery …. was the secret motor, the mainspring of the war.”) Basically, he was a dashing, courageous, even romantic figure whose mixed record as a combat general has earned him admiration and criticism in equal measure.

Born and raised in Kentucky, Hood was a graduate of West Point’s class of 1853. He served as a cavalry officer in Texas, where he was wounded in a fight with Comanches at Devil’s River. Not yet 30 when the South fired on Fort Sumter, the striking Hood — 6 feet 2 inches tall, with blond hair, blue eyes and a thick, long beard — tried to enlist in a Kentucky regiment, only to find that Kentucky wasn’t going to secede. He then joined the Confederate army as a lieutenant.

Within a year, Hood was elevated to brigadier general, in command of a brigade of Texans, which became one of the most storied units of the war. Hard-fighting and hard-hitting, members of Hood’s Texas Brigade were known as Robert E. Lee’s shock troops, authors of stunning, table-turning attacks against Union forces at Fair Oaks, Gaines Mill, the Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam and at the Peach Orchard and Devil’s Den at Gettysburg.

Respected on both sides, the Texans earned their reputation with blood. After Antietam, a fellow officer asked Hood where his division was. “Dead on the field,” Hood replied, and correctly; two-thirds of his brigade were casualties. The division also suffered heavy losses at Gettysburg; Hood himself was hit in the arm, which hung shriveled on his body thereafter.

Hood recuperated in Richmond, Va., where he was warmly received by Jefferson Davis and capital society. One of its central figures, diarist Mary Chesnut, wrote about him in August 1863. “When Hood came with his sad Quixote face, the face of an old Crusader, who believed in his cause, his cross, and his crown, we were not prepared for such a man as a beau-ideal of the wild Texans. He is tall, thin, and shy; has blue eyes and light hair; a tawny beard, and a vast amount of it, covering the lower part of his face, the whole appearance that of awkward strength. Someone said that his great reserve of manner he carried only into the society of ladies. Major Venable added that he had often heard of the light of battle shining in a man’s eyes. He had seen it once — when he carried to Hood orders from Lee.” By September, that fierce light was shining in Tennessee, where Hood again led his Texans in one of their characteristic assaults at Chickamauga. This time Hood lost his leg.

Hood again recuperated in Richmond, where he resumed his courtship of Sally Preston, the beautiful, intelligent, 18-year-old daughter of a wealthy South Carolina family. Buck, as she was known, was staying with Chesnut, and Chesnut very much wanted to introduce Richmond’s It girl to the Confederacy’s Most Eligible Bachelor. Eventually they met on a Richmond street; reportedly Hood studied her and then whispered a comment to a companion, Dr. John Darby. Later, Preston asked Darby what Hood had said. “Only a horse compliment,” Darby answered. “He is a Kentuckian, you know. He said you stand on your feet like a Thoroughbred.”

Hood did court Preston, and the attraction was mutual. Her parents, however, objected; Hood had no money, and was down to two limbs besides. The man who charged the guns of Devil’s Den took no for an answer. Preston said later that if he had proposed to her over her parents’ objections, she would have accepted.

In the spring of 1864, Hood was appointed a corps commander in Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee. Facing troops under Gen. William T. Sherman, Johnston was practicing a strategy of maneuver that avoided conflict while stalling Sherman’s progress to Atlanta. An exasperated Davis wanted Johnston’s army to attack Sherman, and so he sacked Johnston and replaced him with Hood.

What Davis wanted was what Hood did best. Before long, Hood launched four assaults on Union forces outside Atlanta, one more disastrous than the other. Hood’s casualties were so heavy that he could no longer protect Atlanta, and he withdrew, burning the supplies his men couldn’t carry.

With him went the Confederacy’s last chance at winning independence. Little progress had been made by Union forces that year, and the 1864 election was in doubt. Abraham Lincoln believed he was going to lose to a new administration already pledged to negotiate an ending. But when Sherman took Atlanta, Lincoln was saved.

Hood suffered two more catastrophic defeats at Franklin and Nashville before he was relieved of command. After the war, he ran an insurance business in New Orleans married and sired 10 children. In 1879, a yellow fever epidemic swept New Orleans, killing Hood, his wife and their eldest child. The surviving children were split up and adopted by several families. He was 48.

An interesting figure, no? Gallant, romantic, courageous, tragic — one could think of many worse ways to spend a rainy afternoon than to read a novel based on Hood’s life. And who would deny him the honors earned by his service, his dedication, his sacrifice? One would think that on Confederate Heroes Day, which Texas marks every January, much time would be spent recalling Hood’s many virtues.

But continue to name a U.S. Army base after him? No, that time is over.

When Fort Hood was named, the Army was segregated, and our views about race more ignorant. Now blacks make up about a fifth of the military. The idea that today we ask any of these soldiers to serve at a place named for a defender of a racist slavocracy is deplorable. Can we really expect any of our soldiers to tell Afghans or Iraqis that they are there for their freedom when they have come from a place named for a man who fought to keep people in bondage?

More important, we simply should not name U.S. Army bases after people who fought the U.S. Army in battle. Not Hood, not the incompetent Pickett, not the KKK chieftain Gordon, not the sainted Lee. The gesture honors one man, while it denigrates the struggle and the sacrifice of every U.S. soldier who faced him. It mocks them. It mocks the union they preserved.

There are better choices, soldiers whose service and sacrifice reflect the best of our values, rather than the outdated concerns of our ancestors. During the 20th century, 37 U.S. Army soldiers from Texas won the congressional Medal of Honor. To read the citations of their actions causes one’s chest to swell with pride. Any of them would be a better choice than John Hood.

One of them, Capt. Jon Swanson, whose Medal of Honor was awarded posthumously after exhibiting astonishing courage in Cambodia in 1971, was a native of San Antonio and a member of the 1st Cavalry, based at Fort Hood. I suggest the search begin there.

June 14, 2013

MANHATTAN, 55TH STREET BETWEEN 5th and 6th, JUNE 11th, 8:22 PM (SUNSET)

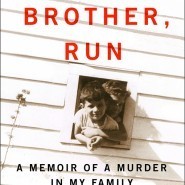

RUN, BROTHER, RUN

Congratulations to my friend and client David Berg on the publication of his excellent new memoir Run, Brother, Run. The book is quite amazing–a funny, tender, perceptive, and angry family memoir about his dysfunctional upbringing, focusing especially on David’s beloved older brother Alan, a smart, talented, funny sharpie with a streak of nobility. When Alan is murdered, however, the book turns into a tense courtroom drama, where Alan receives his justice, of a kind. David is a great storyteller with a rich voice that easily combines humor and

Congratulations to my friend and client David Berg on the publication of his excellent new memoir Run, Brother, Run. The book is quite amazing–a funny, tender, perceptive, and angry family memoir about his dysfunctional upbringing, focusing especially on David’s beloved older brother Alan, a smart, talented, funny sharpie with a streak of nobility. When Alan is murdered, however, the book turns into a tense courtroom drama, where Alan receives his justice, of a kind. David is a great storyteller with a rich voice that easily combines humor and  erudition, and the chapters in which he deconstructs the trial are like watching a football game with John Madden; you not only see the game as it happened far better than you ever could, but you also see the game that might have been. Thanks to my agent David McCormick, who is also David Berg’s agent, I was able to consult on the manuscript and work with David in fleshing some things out. It was a great privilege to work with him, and I enjoyed myself immensely. The book is quite wonderful, and deserving of all the accolades it is receiving.

erudition, and the chapters in which he deconstructs the trial are like watching a football game with John Madden; you not only see the game as it happened far better than you ever could, but you also see the game that might have been. Thanks to my agent David McCormick, who is also David Berg’s agent, I was able to consult on the manuscript and work with David in fleshing some things out. It was a great privilege to work with him, and I enjoyed myself immensely. The book is quite wonderful, and deserving of all the accolades it is receiving.

May 27, 2013

GOOD NEWS–THE WAR IS OVERISH

(This article first appeared on the site of The Washington Monthly on May 26, 2013.)

I liked what President Obama said in his national security speech the other day. I thought it was amazingly courageous for him to talk in terms of ending the war on terror, if for no other reason than that it could literally blow up in his face. It’s so much easier and expedient to do what Bush and Cheney did, and just frighten everyone out of his wits.

I’m glad he decided to put more limits on the use of drones, without barring their use altogether. Terrorism was so frightening because of its asymmetrical effectiveness; all our troops and tanks couldn’t defend against a guy and a bomb. Drones are an effective antidote: we don’t have to deploy 50,000 troops, we don’t have to kill thousands of civilians, we don’t have to smash millions of dollars worth of infrastructure, we don’t end up with thousands of ex-soldiers with PSDT abecoming alcoholics and abusing their wives, we don’t have to stand in endless lines at airports and let TSA agents pat down grandma’s breasts; we just deprive the leadership of safety. It’s necessary that we be careful in its use; it’s essential that we do not rely on it casually. But we should be proud that our military has found a way to protect us, and to bring an end to the war on terror.

I’m also glad that the president spoke up about closing Guantánamo. Every hour that it remains open adds to our shame. Some kind of embarrassing overreaction has happened every time we suffer a national freak out—the Palmer Raids, the internment of the Japanese, McCarthyism, and now Guantánamo. We tell ourselves that our fear justifies the abrogation of our very best values, and off we go, trampling on people. Do you have any doubt that our grandchildren will shake their head in embarrassment at our actions? I don’t. Will they repeat our mistakes when they have a freak-out moment of their own? God, I hope not.

THE USE AND ABUSE OF FREEDOM

(This article first appeared on the site of The Washington Monthly on May 26, 2013.)

Last week David Brooks had an interesting column about a couple of studies that surveyed key words in a body of writings. (No, we’re not talking about tax examiners looking for Tea Party among applications.) He describes the “two elements” that he found:

“The first element in this story is rising individualism. A study by Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbell and Brittany Gentile found that between 1960 and 2008 individualistic words and phrases increasingly overshadowed communal words and phrases. That is to say, over those 48 years, words and phrases like “personalized,” “self,” “standout,” “unique,” “I come first” and “I can do it myself” were used more frequently. Communal words and phrases like “community,” “collective,” “tribe,” “share,” “united,” “band together” and “common good” receded.

“The second element of the story is demoralization. A study by Pelin Kesebir and Selin Kesebir found that general moral terms like “virtue,” “decency” and “conscience” were used less frequently over the course of the 20th century. Words associated with moral excellence, like “honesty,” “patience” and “compassion” were used much less frequently. The Kesebirs identified 50 words associated with moral virtue and found that 74 percent were used less frequently as the century progressed. Certain types of virtues were especially hard hit. Usage of courage words like “bravery” and “fortitude” fell by 66 percent. Usage of gratitude words like “thankfulness” and “appreciation” dropped by 49 percent. ”

The question I have—and would have tried to answer, had not my attempts to find these studies through google led me to data bases that thwarted my efforts to access the pieces—is this: how did the word `freedom’ do?

One of the biggest changes in my adult life is what has happened to freedom, not just as a word, but as a value. It is, it seems to me, the only value Americans put much stock in. Equality, in which immigrants and labor unions invested so much energy and support and devotion during the first part of the 20th century, now seems a hostage of identity group politics. Freedom is it—it’s what we appeal to for everything, from gay marriage to Wall Street shortcuts to environmental pollution to smoking pot to war (Free Kuwait! Iraqi freedom!) These are the years of freedom triumphant, and boy, if anything explains the mess we’re in, it’s freedom. Try arguing for something in terms of Community, or Sacrifice. Go to Congress and make a case for Majority Rule, and you’ll get an earful from Ted Cruz and Rand Paul about the freedom of the minority to thwart the majority.

More than anyone, Ronald Reagan put us on this path. I can’t imagine a figure who would be able to get us to rebalance our values.

STILL FIGHTING THE SLAVEHOLDERS’ REBELLION

(This article first appeared on the site of The Washington Monthly on May 26, 2013.)

As it happens, I have an article today in the Times’ review section wondering why we continue to have US Army bases named after Confederate generals. There are at least ten: Forts Lee, Pickett and Hill in Virginia; Fort Bragg in North Carolina; Forts Gordon and Benning in Georgia; Fort Polk and Camp Beauregard in Louisiana; Fort Hood in Texas and Fort Rucker in Alabama. Some of these men were good generals, but most were mediocre at best. Most were ardent secessionists, some were slaveholders (Polk had several hundred), one was an accused war criminal, one became a leader of the KKK. But whoever may want to honor them, whatever they may want to honor them for, it does seem singularly preposterous to name US Army bases after men who led troops in battle against US Army soldiers.

As the writers among you know, the material one gathers in researching a piece often overwhelms the amount of space one gets to write, and that was the case here. For example, I learned that nine states—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas—officially observe a separate Confederate Memorial Day. They fall on several different days, often consistent with when the flowers bloom, although in Texas it is commemorated in January, where the day is called Confederate Heroes Day. In Mississippi and Alabama, the birthdays of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert E. Lee are celebrated together. Several states mark Jefferson Davis’s birthday in June, including Kentucky. Davis was born in Kentucky, but Kentucky never seceded from the union. Lincoln was born in Kentucky, too, but there is no separate holiday to mark that occasion.

What do the people in those states think they’re honoring? And in the case of the war dead, why do they need a separate day to do so? What does the separateness indicate?

If President Obama maintains tradition—and so far during his presidency, he has—tomorrow he will send a wreath to the portion of Arlington cemetery allocated for confederate soldiers. This confederate section was originally the result of some magnanimity on the part of President McKinley, a former US Army sergeant who fought at Antietam, who proposed that he federal government take over the care of confederate gravesites in the north. One result of this was the disinterment of bodies from several sites around Washington, including Arlington, and reinterment in this section at Arlington. Along the way, the Daughters of the Confederacy got involved and arranged for Moses Ezekiel, the most respected American sculptor of his day, to built a 32 foot statue on the site.

It’s an amazing statue, featuring one larger-than-life and 32 life-size figures, showing people in postures of pride, grief, sadness and courage. Among them is Minerva, the Roman goddess of war. She holds a spear in her right hand, and in her left arm is an obviously wounded woman. In the wounded woman’s left hand is a shield prominently labeled “U.S. Constitution,” a fairly direct statement of the view that the forces who wounded the woman were warring against the Constitution. The statue also bears a Latin inscription, which translated reads “The victorious cause was pleasing to the gods, but the lost cause pleased Cato.” This is a reference to the Roman civil war, in which the dictator Julius Caesar defeated the Pompey, and to Cato, respected as the most honest Roman of them all. In short, it says the wrong side won. But when that statue was finished, President Wilson, a native of Virginia, came to the dedication and placed a wreath at its foot, a Memorial Day custom that every president has followed.

I don’t know why so many people in so many southern states feel obliged to keep one foot in the past, to compartmentalize defenses and excuses for beliefs and behavior that should have been buried and forgotten long ago. But it is more amazing that those of us who not not share in those beliefs so mindlessly acquiesce in their preservation. We should not have US Army bases named after confederate generals. The US president should not send a wreath to sit under a statue that argues in a sneaky Latin fuck you that the United States was wrong to preserve the union, and to force an end to the slaveholders’ rebellion.