Robert V. Camuto's Blog, page 6

October 7, 2022

Into the volcano

October 7, 2022

Into the volcano

Around the surreal landscape of Naples

In the last decade, Sicily’s Mount Etna has exploded into Italy’s hottest wine scene. Volcanic wines have become a geeky fashion statement.

But a lot of so-called volcanic terroirs – like Germany’s Mosel – come from eruptions hundreds of millions ago.

Solfatara is one of the largest active craters in Naples province with smoldering plumes of sulforous gas

Does that really count as volcanic? To me, there’s is a big difference between “volcanic origin” soils and viticulture on an actual active volcano.

In the latter category you have the Naples are – a crazy surreal landscape of still fuming craters starting with the Campi Flegrei – 80 square miles of active supervolcano with dozens of craters alongside homes, schools, roads and vineyards.

“This is not like Etna where you look up and see the volcano. Here you live in the volcano,” says Gerardo Varchetta, the 46-year-old winemaker at his family’s Cantine Degli Astroni winery.

This goes a long way to explain the live-for-today attitude of Neapolitans and why local wines – mostly red Piedirosso and white Falanghina haven’t typically got much age on them.

Gennaro Schiano of Cantine del Mare

Pop the cork and carpe diem.

I love the Naples area and enjoy these easy drinking wines from Campi Flegrei to Vesuvius chiefly red Piedirosso and white Falanghina. But for many reasons they haven’t attracted the international scene that Etna has.

For more on the ins and outs of Naples volcanic terroirs, see my latest Robert Camuto meets… (free) at winespectator.com.

share this

social

social

more articles

September 28, 2022

From Prosecco Wars to Pingus

The world has a lot of problems right now. Among them war at the edge of Europe.

So, I don’t think the Prosecco wars — i.e. Italian Prosecco producers fighting to guard the Prosecco name – is among the biggest.

Nevertheless — as I write in the latest Robert Camuto Meets… column at winespectator.com — I recently got drawn into the debate over provisions in a bottom-of-the-headlines trade deal between the EU and New Zealand that clinched the name Prosecco for Italy.

This might seem like a no-brainer, but it’s ambiguous. Prosecco was the name of a northeastern Italian grape before it got flipped into the name of a sprawling wine region within the last decade of Prosecco boom.

Australia’s nascent Prosecco scene — started by Italo-Australians — is crying foul.

Australia’s nascent Prosecco scene — started by Italo-Australians — is crying foul.Of course, what we call stuff is important when it comes to origins and quality. And it’s been the focus of battles from Champagne to Parmesan to cheese to Neapolitan pizza to Philly Cheese Steak. I think Prosecco is within its rights. But there are limits. I agree that the names of grapes (like Vermentino for example) should remain open and free of trademark to all growers.

Speaking of sparklers on the international scene, my wife and son, his friends, and I recently shared a bottle of Hambledon “Classic Cuvee” from Sussex, England at our favorite London wine restaurant — Noble Rot in SoHo.

The other Camuti in our group appreciated the wine’s tart character. But for me it was like most of the English sparklers I’ve tried — lacking the depth and creaminess I love to find in Champagne. (Although admittedly, I haven’t spent much Sterling on English sparklers out of fear of being even more disappointed.) With the currency falling, it might be a good time to try more. My mind is open.

Peter Sisseck of Pingus

Peter Sisseck of PingusIn other news… one of the more open-minded and interesting winemakers I’ve ever met is Peter Sisseck — the Dane who launched and leads Spain’s Dominio Pingus in Ribera del Duero.

My profile of Peter – a man who bought cows to have his own fertilizer and soon found himself growing grain and producing cheese — is in the October 31 edition of Wine Spectator, on newsstands now.

share this

social socialmore articles

September 14, 2022

Getting nostalgic for the future

September 14, 2022

Getting nostalgic for the future

Being a conservative progressive isn’t a contradiction when it comes to food, wine and life in Italy

Last week in Naples, fellow American wine writer Alder Yarrow asked me this :

Was not my latest book, South of Somewhere: Wine, Food and the Soul of Italy based on a kind of nostalgia for a way of life that was dead or, at least, dying ?

No, I said.

It was late. We’d been drinking, and we were sharing a ride back to our respective hotels in the crazy volcanic landscape of the Campi Flegrei. In the following days I thought about his question some more.

First off, I loathe nostalgia — that dangerously deluded mindset that ignores the way things really were in the “good old days.”

Rather, I think it’s important to look back to understand the present. Today’s 21st century wine scene in Italy — to me a golden age of wine quality — didn’t come out of nowhere but was built on the shoulders of past generations.

Let’s be clear : up until very recently old-world wine growing was mostly misery. What are dead — thankfully — are the oppressive systems like sharecropping existed across much of Italy years after World War II and the use of arsenic as pesticide that persisted decades later.

In South of Somewhere, Elena Fucci’s father, Salvatore, recounts the 1960s : “People here sold the grapes, and they starved.”

What I see across Italy today are new generations of producers intelligently taking up the work of their grandparents with a respect for the better traditions, nature, and others. These neo-contadini (farmers) and wine entrepreneurs have degrees and smarts and are savvy about how to bottle their own wine and connect to the world.

Now, more than ever, it is possible for contadini to live a life of dignity.

I am as optimistic about the present and future generations as I am disappointed in my own generation of Baby Boomers for failing to live up to our promise. (In many cases willfully embracing denial and — yes — nostalgia.)

When I see young people here willingly — joyfully — taking up the hard task of cultivating and vinifying in their towns and villages — that gives me hope.

Nostalgia for the Future means taking the lessons and the good of the past and carrying them forward with a vision of tomorrow.

As the composer Gustav Mahler said at the turn of the 20th century, “Tradition is not the worship of the ashes, but the preservation of the fire.”

I say: Viva the flame.

Looking back and forward

It was a great joy this last weekend to present the Italian version of South of Somewhere, called Altrove a Sud, in the place where Italy began for me : my maternal grandparents’ beautiful Vico Equense on the Sorrento coast.

Robert and journalist Fosca Tortorelli before the presentation

Taurasi Maestro Luigi Tecce (left)

It was for me, and I hope for those present, a “bella serata” in the stately atrium of Vico’s old City Hall – beginning with a discussion led by Campania journalist Fosca Tortorelli and followed by an “aperi-vino” with wines from the Amalfi Coast’s Marisa Cuomo, the Fiano whisperer Sabino Loffredo of Pietracupa, Aglianico maestro Luigi Tecce, and Campania’s modern leaders Feudi di San Gregorio.

Public speaking in Italian to an Italian crowd can be taxing—my brain often aches as it searches for the right word at the same time that my mouth is moving. So, part of me couldn’t wait to “wrap” this one. Another part of me didn’t want it to ever end.

The adventure continues in my twice-monthly column at winespector.com. Dive in!

share this

social

social

more articles

August 25, 2022

Etna keeps erupting

August 25, 2022

Etna keeps erupting

The volcano continues to catch young winemaking dreams

My wine friend Brandon is as crazy about Sicily as I am. He’s an American who came to the island in his youth to work at the Sigonella U.S. Naval Air Station and never left.

Brandon, whom I wrote about in my book Palmento (2010) along with some of his romantic and wine exploits, may have the most extensive collection of Etna wines anywhere. Now retired, Brandon knows almost everything that moves on Etna. It’s rare to find a wine on the mountain he hasn’t sampled.

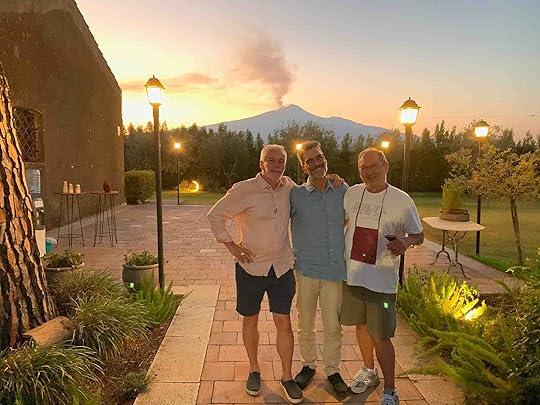

Brandon Tokash (right) with me (center) and Etna winemaker Frank Cornelissen

Brandon and I both get something like a high off the fact that the mountain continues to attract young and wide-eyed novices undaunted by the hard work of making wine on the rugged slopes of Europe’s most active volcano.

On a recent trip to the mountain, Brandon connected me to some of Etna’s newest and smallest producers in Michele Calabretta — a Passopisciaro native son and accomplished auto-tech engineer — with his wife German wife, Claudia. Now 41, and with three small kids, they are in their fifth vintage at tiny production Boccarossa.

Michele Calabretta and his wife Claudia Langer Calabretta with their son Marco

“We had to something,” is how Claudia summarizes their adventure that began as a game among a group of friends.

It’s the stuff of romance that enlivens one of Italy’s already liveliest wine scenes. And keeps a lot of us – including Brandon and me — coming back for more.

Read more about Boccarossa and some other Etna recent developments in my new Robert Camuto Meets… column at winespectator.com

share this

social

social

more articles

August 3, 2022

Ice it !

August 3, 2022

Ice it !

In Summer, forget the ridiculous concept of red wine at “room temperature”.

One of my obsessions for years now has been the insane orthodoxy of always serving red wine at “room temperature” — no matter the conditions in the “room.”

In Southern Europe the average no a/c room these days may be something like 80 degrees F — a temperature that makes red wine taste like barbecue cleaner or some other household product not fit for mammalian consumption.

Yet, red wine is still often served way too warm on both sides of the Atlantic. It seems like with climate change and the ice caps melting, some restaurants, trattoria, and bistros are getting skimpy with the ice ! (Saving it for the end times?!)

The failure to serve red wine at a proper temperature (I like 15C, 59F) has fueled the boom in a lot of vapid rosé — a wine no one would dare serve too warm.

So while I don’t actually resort to ice cubes in the glass, I DO ABSOLUTELY want my red wine chilled either in the fridge or an ice bucket.

Read more about all that in my latest Robert Camuto Meets… at winespectator.com

And happy sweatin’.

share this

social

social

more articles

July 27, 2022

The Last Leopard

July 27, 2022

The Last Leopard

Lucio Tasca d’Almerita (1940-2022)

On a long, hot afternoon in Sicily Monday, I was having lunch in the old palmento of the Mannino family amid the citrus groves of their Tenute Del Gelso below Mount Etna.

The caponata and other appetizers were making the rounds of the table as a fan in the corner kept the dense air moving. Family wines from the Manninos’ Tenute Mannino di Plachi on Etna were poured. A toast was made.

And then someone’s smart phone alerted them to the news: Lucio Tasca, of Sicily’s Tasca d’Almerita wine family was dead at 82. Giuseppe Mannino, the family patriarch, set his glass down and sighed.

“It’s a big loss for Sicilian viticulture,” he said softly.

Lucio Tasca d’Almerita (1940-2022)

Lucio Tasca d’Almerita was perhaps the last in a string of patriarchs who brought Sicilian wine into a modern age along with the likes of Diego Planeta of Planeta and Giacomo Rallo of Donnafugata — both who have died in the last six years.

From its base at Regaleali in the central Sicilian hills, Tasca D’Almerita has become a model of sustainability with wine estates across Sicily including Sallier de La Tour in Monreale and Fondazione Whitaker on Mozia island, Mount Etna’s Tascante, and Capofaro on Salina island.

I spent some time with Lucio and the Tascas when researching my 2010 book Palmento: A Sicilian Wine Odyssey , and what struck me most about him wasn’t so much his wine passion, but his gentlemanliness, elegance and frankness along with his ideas of a modern Sicily.

He led off the chapter titled “Where have the Leopards Gone?” which I excerpt here.

“Gattopardo doesn’t exist anymore. He is dead.”

The Count Lucio Tasca d’Almerita surprised me with these words. Because if anyone would preserve and protect the ideas of The Leopard, I assumed it would be him. After all, everyone from Sicilian laborers to politicians, quoted Giuseppe di Lampedusa (whose mother was a Tasca) more frequently than the Bible. I expected therefore the noble overseer of one Sicily’s largest old estates—to embody The Leopard and its view of Sicily as immutable.

“My father could have been Il Gattopardo. This is a stupid thing,” he continued, “In fact, Sicily is changing. “

At 68, Count Lucio who dismisses the use of a title before his name with the wave of a hand and a “just Lucio” looks the part of a count with his head of healthy silver hair, the light eyes peering over a significant nose and his hint of world weariness. A blue blazer and an open white shirt with gold pants cover the long and agile frame that served him in his days riding steeplechase on the Italian national team. Though he has retired from running the Tasca d’Almerita estates—turning the job of chief executive over to his younger son, the 36-year-old Alberto--Lucio is a businessman with little patience for philosophy or reflecting on the past. A flat computer screen rested on his desk which was an arc of polished wood. His English is near perfect but he explained his French is better; he asked if I minded if he took off his jacket and rested it on the back of his chair. He pushed a button on his desk phone and asked for coffee—a secretary soon arrived with espressos in un-Leopard-like disposable plastic cups. He settled back in the steel framed desk chair, opened a window to the bright early summer morning, and after a do-you-mind-if-I-smoke courtesy, ignited a Marlboro Light, the modern affliction, it seems, of all Tasca men.

Despite the “just Lucio,” three generations of Tascas live an anachronistic life with cooks and staff in town and country. Town is Villa Tasca, the 16th century palazzo from which Count Lucio and I drove a few hundred yards to this office. The villa is one of Palermo’s grandest with lush gardens at the edge of town insulating it from the blight of apartment blocks and industrial parks just outside. The family’s country life is based at Regaleali, the 1,200-acre estate in the remote wheat-covered center of Sicily with about 900 acres of Sicily’s most important ecologically run vineyards.

Yet the Tascas are one of the only aristocratic families to keep a vast wine estate intact in the 21st century—even after more than half of it was taken from them under Southern Italy’s postwar land reform program in the 1950s. The Tascas, it seemed, have thrived with the right blend of instincts—adapting to the times when others bemoaned them.

“We always worked,” Count Lucio said, explaining his family success as other Sicilian dynasties have gone broke. “They never worked.”

The Tascas came to their title and their Palermo villa in the early 19th century. A previous Lucio Tasca—a wealthy cattle rancher from Mistretta in the Nebrodi mountains of northeastern Sicily—arrived in Palermo with good looks and money and married the daughter of a Sicilian prince, who brought the Villa—then known as Camastra-- as her dowry. At the time, feudalism and Bourbon rule was on the wane, baronial lands were being sold and Sicily was in a state of turmoil as many Spanish families associated with the Bourbons left. In 1830-- a pair of Tasca brothers—bought the old fortified farm at Regaleali.

The family’s main interests were in grain and other agricultural products. Wine-- grown in the lands around Camastra now paved with concrete-- was cultivated for the family and to accompany estate workers during their labors. As a young boy at Regaleali after the War, Lucio remembered the daily ration to laborers of one kilo of bread and one liter of wine.

“Wine was food for them,” he said. “They drank it all day long.”

“I remember this worker cutting up one olive in such a way to last for one kilo bread—the whole day,” Lucio said, using his hands to illustrate a surgical slicing motion with an imaginary knife.

Around 1920 all of the Camastra production including wine had moved to Regaleali. After Lucio’s birth at the outbreak of the war in 1940—about 80 people including relatives, close friends and workers’ families moved there as well. After the war Lucio’s grandfather and father “made revolution”—instigating in the Sicilian separatist movement and its doomed pair of secessionist plans: first to be annexed by the United States and later to have the deposed Italian King Umberto II installed as king of an independent Sicily.

Some historical accounts have linked members of the aristocracy including the Tascas with the bandit Salvatore Giuliano (Lucio’s father, Count Giuseppe, served as a consultant to Michael Cimino for his screen adaptation of The Sicilian). But Lucio says he never saw Giuliano at Regaleali, and said that if a relation did exist it was a matter of practical convenience.

“When you make revolution, you need to have some people who know how to kill,” Lucio said, matter-of-fact.

The Tascas were not great political revolutionaries. They were, however, revolutionary in the stewardship of their lands—bringing one of the first tractors to central Sicily before the war, and building one of the first high country lakes in the years after. In those postwar years, while the government created cooperatives and handed out subsidies for producing more wine, the Tascas instead worked to produce better wines. They shunned herbicides and pesticides, introduced vineyard techniques such as short pruning of vines that improved quality and limited quantity of fruit, and were among the first to limit the heat effects on wine with cold fermentation tanks.

Count Giuseppe was the wine lover who transformed Tascas' wines – and in so doing left a lasting mark on Sicily. In the early 1960’s—enlisting the help of Ezio Rivella, one of Italy’s top oenologists -- he began bottling white wines from Inzolia, Catarratto and a grape variety on the estate they called Sauvignon Tasca (believed to be a cross of Sauvignon Blanc with Grecanico). Among Giuseppe’s favorite wines were reds from Châteauneuf -du-Pape in France’s Rhone Valley, and in 1970 he began bottling a red wine (the first bottled from 100% Nero d’Avola) called Rosso del Conte.

“We don’t work for money,” His son, Lucio, was now telling me with another wave of the hand. “We have never worked for money.”

“We work,” Lucio said, “for what we Italians call la bellezza di lavoro.” (“The beauty of work.”)

Unlike his father, Lucio is not an obsessive wine lover. He studied economics – not agronomy or oenology. Wine, he freely admits, is something he enjoys a few minutes of the day with meals. His love is the land, his business, and la bellezza that is evident throughout the Tascas' growing world.

As a younger man he had worked briefly for his father but then launched other small businesses-- wholesaling nursery plants and textiles from Villa Tasca.

“I was married and had two children, but I couldn’t talk with my father about money, so I did other things,” he said. “Also there was always competition between my father and me.”

Finally, approaching 40 years old in 1979, Lucio joined his father at Regaleali. “Back in 1980,” he remembered, “if you went around the world with a bottle of Nero d’Avola people weren’t interested. People-- the Americans-- were just starting to learn about the French cepages (varietals)… Nobody could imagine that in Sicily you could make a good wine. They thought you could only do it France.”

Thinking that if the world wanted French varietals, Regaleali could produce them, Lucio asked his father to experiment with other grape varieties.

“He gave me half a hectare at Regaleali—one acre,” a smile creased the Lucio’s face. His long fingers toyed with the Marlboro pack on his desk. “The Chardonnay and Cabernet were wonderful.”

Next, Lucio wanted to experiment with raising wine in small French oak barriques.

“My father said, ‘If you bring barriques to Regaleali I will leave,’” Lucio remembered. The wines at Regaleali were traditionally aged in large chestnut or Slovenian oak botti. Lucio had to trick his father by hiding French barriques he’d bought with his own money. He later had his father blind taste his experiment: The barriques and the count stayed…

I am reading this now and remembering both Lucio and the other greats of his generation whom I had the fortune to meet on Sicily. None of them were Gattopardo, really.

But in a romantic way, I think each contributed to bringing the best of Sicilian tradition into the 21st century.

share this

social

social

more articles

July 21, 2022

It’s Hot.

July 21, 2022

It’s Hot.

Hell Yeah. What to do ?

“Fa un caldo da morire!!!” cried the greengrocer woman with the picture on the wall of Mussolini holding a baby.

Was that her — Signora Fruits and Veggies — as an infant, I wondered ?

Yeah well, I know its deathly hot. But you’ve got a picture — possibly a childhood memory – of Il Duce, which should be verboten. But it’s not — such is Italy’s relationship with its fascist past. Anyway, I am buying a big piece of Anguria (watermelon) here anyway, along with your cold caponata, because these things are essential.

That’s my take anyway. I can survive a heat wave, with a shortlist of cold things. GRANTED, I do not have to any heavy work in the outdoors other than writing the occasional complex sentence. I am grateful for that. Also, I have never ever been threatened by a wild fire.

So, as long as I am not having to do construction or battle a fire, I am fine with waking really early and passing the day with cold watermelon, Sicilian almond granitas, chilled wines (including reds placed up to an hour in the fridge), well-made small-batch beers (like those at Allez Hops shop in Nice, France – a craft beer shop and brewery run by my friends Dan and Julie (who designed and manages this website).

Speaking of cold things and kind people, do check out my new column at Wine Spectator on the Mustilli sisters – whose Dad resurrected Falanghina decades ago.

The Mustilli sisters Paola (right) and Anna Chiara (left) in Falanghina vineyards

The column starts like this :

I was hot and thirsty one late afternoon in the ancient city of Benevento, in the middle of the ankle of the Italian boot. So I walked up to the shaded terrace of a café for something cold.

“Some San Pellegrino,” I called out in Italian to the barman standing in the doorway.

“Bianco o rosso?” he asked. He apparently thought I wanted wine, possibly confusing my request for water with the famous Marsala-based Sicilian producer Pellegrino…

I was going to write some pithy “kicker” of an ending to this post, but I think I’ll avoid working up that sweat. Just read the column.

share this

social

social

more articles

July 11, 2022

From the South of Italy to way way north in the Atlantic

July 11, 2022

From the South of Italy to way way north in the Atlantic

Did I say Canada ?

Summer travels took me from Campania’s sweltering Mediterranean coast to a place I’d never really thought of going until recently : northeastern Canada’s cool-clime Newfoundland and a series of remote islands in the North Atlantic.

Starting in Saint John’s, more than 600 miles Northeast of coastal Maine, my wife (this was all her plan) and I embarked on a 10-day Adventure Canada cruise that featured Birdlife International and A.C.’s frequent artist in residence: the still intellectually vibrant and feisty Canadian writer/icon Margaret Atwood, at 82.

Hiking on Saint Pierre and Miquelon – France's last archipilego off North America

Much of the time on Soviet-era ferry the Ocean Endeavor, we were off the telephone and internet grid, but smack in the middle of networks of dolphins, whales, puffins, wild horses (of Sable Island) and seals.

There is something about beholding such creatures in action – say a humpback whale beating its tail against the surf and breaching skyward, or a white-sided dolphin seemingly changing colors as it glides alongside the ship – that gives you something like hope.

It also makes you want to do something about mankind’s invasive imprint. On virtually uninhabited Sable Island for instance, a team is studying debris including grain sized pieces of plastic and other synthetic junk that beaches there. (Where did that headless Barbie originate?)

Drinking Canadian at Saint John's Mallard Cottage

On the wine front, we drank Canadian — picking up wine whenever we docked near a town with a wine/liquor store. Canadian wines are mostly Bordeaux blends and Burgundy monovarietals (the best examples from the west coasts’s British Columbia as well as Quebec with some strange and trendy wines like bubbly (refermented) piquette thrown in the mix.

Newfoundland has a small but creative food and beer scene. One of the more interesting named breweries is the Dildo Brewing Co. located in the picturesque coastal town of Dildo (pop 1,200 – about 60 miles west of Saint John’s). One theory about the historic town’s name origin is that it comes from the French name for the island — Ile d’Eau – for its abundant fresh water.

Speaking of water, as much of the U.S. and Italy suffer this summer from drought, it is worth noting that Canada holds about 20 percent of the planet’s freshwater reserves.

Yet, surprisingly, Canada isn’t yet building a wall on its southern border, and proclaiming “Stay away from our water!”

This may be because Canadians (save the occasional Quebecois who takes offense at the speaking of English), tend to be unfailingly polite. And genuinely nice. That goes ten-fold for Newfoundlanders.

Canada does have proud Dildoians. But, it seems, fewer dicks.

At the Dildo boutique in Saint John's

Maybe there’s a humility that comes with being north of a Superpower neighbor — that prides itself as “the greatest.” Canadians are spared such ambition, and judging from their Canada Day commemorations, they seem sincerely interesting in wanting to do better.

In the U.S. you might say we learn a love of country. Canadians seem to love their land.

That love of place is a common theme in my wine writing from the Old World and Italy. I see wine not as just a drink but a way of managing and valorizing the landscape. And I think that is enriching and important in our world.

Check out the latest installment of my Robert Camuto Meets… column on the evolving style of Sagrantino in Umbria’s Montefalco.

share this

social

social

more articles

June 29, 2022

California Diaries 2022

June 30, 2022

California Diaries 2022

New wave producers with Italian Grapes in the Golden state

In the spring of 2022, I travelled from one end of California wine country to the other with a burning question : Why aren’t there more vineyards planted to Italian varieties in California’s Italy-like climes ? Alot of that has to do with grapenomics and decisions made a generation ago. But today that is changing thanks to a New Wave of adventurous Italophile producers.

Part 1

“A Slice of Southern Italy in Paso Robles”

Part 2

“Brining the Mediterranean to Northern California"

Part 3

"Capitalist Keven and Doomsday Dan"

Part 4

A Pair of Pioneers Translate Northern Italy into Santa Barbara

share this

social

social

more articles

June 22, 2022

A Napa Son under Umbrian Sun

June 24, 2022

A Napa Son under Umbrian Sun

Just before Covid Rollie Heitz moved to Umbria and is making wine. He hasn’t looked back.

In early spring, I travelled to California where I wrote about a new generation of California producers working with often obscure Italian grapes in the Golden State.

Rollie and Sally Heitz in their Umbria vineyard.

Recently I reported on a different kind of story: A son of old Napa, whose spending his retirement years and making wine in the obscure Umbrian wine appellation of Todi.

Rollie Heitz, of Napa’s legendary Heitz Cellar, was tired of rising rents and congestion of Napa. A trip to Todi and a visit to California artist turned winemaker Ev Thomas there convinced him to start a new wine life this side of the ocean.

For Heitz’s reflections on his move, Umbria and Italian wine, see my latest Robert Camuto Meets… column at winespectator.com

In his tasting room with a view Hietz opens a bottle of afternoon rosato.

share this

social

social

more articles