Candace Robb's Blog, page 14

February 3, 2015

Why I Do What I Do

In case you missed it, Michael Evans recently interviewed me for the Medievally Speaking blog. He caught the flavor of the exchange so well in the title, using a quote from one of my responses: “My fiction is the natural outgrowth of my fascination with the times.” So true!

You can read the entire interview here: http://medievallyspeaking.blogspot.com/2015/01/my-fiction-is-natural-outgrowth-of-my.html

I’ll be exploring some of the issues that arose more fully here. Stay tuned!

And, in case you’ve forgotten who Michael Evans is, here’s a link to the Q&A he did for my blog: https://ecampion.wordpress.com/2014/08/11/interview-michael-evans-on-the-mythic-eleanor-of-aquitaine/

January 18, 2015

Delight in Community

Looking back on 2014, I want to thank you, my wonderful readers and contributors, for such a lively and enjoyable year on A Writer’s Retreat! I didn’t expect blogging to be fun–but the sense of community you bring to it makes it so.

Toward the end of December WordPress creates an annual overview of activity on my blog. Some highlights: “A New York City subway train holds 1,200 people. This blog was viewed about 8,000 times in 2014. If it were a NYC subway train, it would take about 7 trips to carry that many people.” Not sure about that particular comparison, but the numbers are nice! And “The busiest day of the year was December 23rd with 118 views. The most popular post that day was ‘Q&A with Paul Strohm, author of Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury.’ ” Very satisfying.

But that post was only the 4th most read post for the year. For the second year in a row,

#1 was a post from July 2010, shortly after I started the blog: Lincoln green and Robin Hood.

#2, my interview with Michael Evans, The Mythic Eleanor of Aquitaine, celebr ating his new book, Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post-Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

ating his new book, Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post-Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

#3 was The Beguines of Medieval Paris, a guest post by the author of that book, Tanya Stabler Miller.

#4 the Q&A with Paul Strohm,

and #5 was Background on The King’s Mistress, also from July 2010.

Hm, the second month of my blog was rather stellar!

The blog has been viewed by readers in 79 countries, the greatest numbers from the US, UK, and Italy.

Looking forward, I have already approached several guest bloggers, and hope to host even more than last year. My mission is to spread the word about what scholars in the fields I mine for information and inspiration are up to, primarily in wome n’s history, but not exclusively.

n’s history, but not exclusively.

And what else? What you would like to read about here regarding writing, medieval history, folklore, literature, women? My goal is to complete two crime novels this year, so I can’t promise I’ll get to everything you suggest, but I’d love to see your ideas!

January 13, 2015

Shoptalk: Use the Energy That’s Present

Welcome to a new year on A Writer’s Retreat!

I’ll be back with a longer post later this week, but do check out my essay published in Biographile’s “Write Start” series. I was fortunate to meet a wise, perceptive dharma teacher as I was tackling the first draft of The King’s Mistress, a project I’d been stalling over for a long while. In this essay I share her simple advice that turned fear into joyous engagement.

December 22, 2014

Q&A with Paul Strohm, author of Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury

It is my great pleasure to welcome Paul Strohm to A Writer’s Retreat for a Q&A about his new book Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury (Viking 2014).

A little background: Paul has taught medieval literature at Columbia University and was the J. R. R. Tolkien Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University. You’ll find a list of his books embedded in the following interview. Chaucer’s Tale is a microbiography of Chaucer that tells the story of the tumultuous year that led to Geoffrey’s creation of The Canterbury Tales. In 1386, Chaucer was swept up against his will in a series of disastrous events that would ultimately leave him jobless, homeless, separated from his wife, exiled from his city, and isolated in the countryside of Kent—with no more audience to hear the poetry he labored over. This is the story of what he did about that, and how he came to that decision.

A little background: Paul has taught medieval literature at Columbia University and was the J. R. R. Tolkien Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University. You’ll find a list of his books embedded in the following interview. Chaucer’s Tale is a microbiography of Chaucer that tells the story of the tumultuous year that led to Geoffrey’s creation of The Canterbury Tales. In 1386, Chaucer was swept up against his will in a series of disastrous events that would ultimately leave him jobless, homeless, separated from his wife, exiled from his city, and isolated in the countryside of Kent—with no more audience to hear the poetry he labored over. This is the story of what he did about that, and how he came to that decision.

Q (Candace): You seem comfortable moving between medieval literature and medieval history in your writing, your works often a unique mixture of the two (thinking of Social Chaucer, England’s Empty Throne, and, of course, Chaucer’s Tale). Did you begin your studies with the dual interest, or did the literature lead you to a curiosity about the history?

A (Paul): Well, I was an undergraduate history major but kept wanting to write about literature and so I switched to English for graduate school. But I kept coming across questions in literary texts that seemed to require some historical knowledge for an answer. I’m a great believer in the pressures the world beyond the texts exerts on the text–expressed not just in the kinds of factual things you footnote, but also on textual deformations and even on the text’s whole configuration. History’s effects are sometimes veiled–I talk about its influence on the text as an “absent pressure,” but it’s still there.

Q: Your subtitle succinctly summarizes your thesis. Because of a confluence of events in 1386, Chaucer wound up living in the Kent countryside, far from the stimulations of London and his familiar audience. And that’s where he began writing The Canterbury Tales in earnest. Which came first, your curiosity about why he chose to write such a collection of tales toward the end of his career, or your awareness of what an annus horribilis 1386 was for Chaucer?

A: I was initially interested in what a terrible year it was, that practically everything that could go wrong went wrong for him. But then I asked, how did he handle it? And that’s when it dawned on me that at the end of this year he began the Canterbury Tales, and I started looking for a connection. The absence of his customary audience and the importance of his invented one is where I went with that.

Q: Chaucer the royal esquire, controller of customs, member of parliament, and husband of Philippa Swynford comes off as a bit of a sad sack in Chaucer’s Tale. For example, wrapping up the chapter “The Wool Men,” which chronicles business antics rivaling anything we read about today, you conclude that: “a balanced view of Chaucer’s performance in office [controller of customs] would have him neither as a hero nor a villain but as a man who kept his head down, an enabler. ” (p. 136) Is this what you expected to see when you started looking into his career in the customs? Were you surprised, disappointed? How has this deep research affected how you read Chaucer?

A: He was more of a survivor than an ethical hero. But that’s what we would want from him, isn’t it? That he survive, to write those wonderful poems! Maybe the first obligation of a great artist is to find ways to keep making art.

Q: Chaucer was writing in an environment as uncertain as the one in which we write today. As you note: “The 1380s were a crucial decade for literary change in England, and Chaucer’s literary situation was as volatile as everything else in his world. New ideas about writing authorship, audience, circulation, and personal renown were in the air. Writing in English—an unusual decision when Chaucer made it in the 1360s—was taking hold, and demand for works in the native language beginning to grow. Technologies of literary circulation were in rapid development, encouraging the copying and circulation of manuscripts to larger and farther-flung audiences. Chaucer’s literary contemporaries were beginning to think differently about claiming credit for their work. Taken together, these developments began to suggest new ways of being a writer, new stagings of a literary career. (p. 185)” So I just have to ask, did you find his solution, “to maken vertu of necessitee,” encouraging in your own approach to the changing environment we face today?

A: For Chaucer, the idea of an anonymous audience out there reading his work and forming conclusions about it when he wasn’t there to gauge response was extremely unsettling. You can see that at the end of Troilus, when he realizes that he’s written a poem with a potential for more general circulation and goes kind of haywire about the whole thing, troubling himself about scribes miscopying it, and praying (although not very hopefully) that it be properly understood. He was accustomed to a more intimate author-audience situation. Of course everybody then got used to absent and anonymous audiences in the age of print. But now electronic circulation is throwing the situation up for grabs in another way. In the era of the bound book, an entire apparatus of publishing houses and print advertisements and respected book reviewers played a role as cultural go-betweens, directing books toward the audiences most likely to appreciate them. Now, with the internet and e-books and readers encouraged to do their own pop-up reviewing, it’s more of a free-for-all. Everybody has a say, or can have a say if they want one. You can bet I’m taking some nervous looks at Amazon and Goodreads reader reviews, and that’s a factor that didn’t exist five years ago.

Q: Who is your audience? is a question I asked of my students in freshman comp, the scientists and engineers I edited in a laboratory, and my creative writing students, and that my editors ask of me. Until Chaucer’s exile to the Kent countryside his audience had been Londoners and perhaps the royal court. Suddenly, he had no audience. When I came to the section “No Audience? Invent One.” I thumped the arm of my reading chair. Yes! Of course! “He will keep on writing—but for an audience of his own invention. Its members will be the vivid portrait gallery of Canterbury Pilgrims—hearers, tellers, judges, and occasional victims—a body of ambitiously mixed participants suitable for a collection of tales unprecedented in their variety and scope. It will live within the boundaries of his work, perennially available as a resource for the telling and the hearing of tales. Above all else, it will be a portable audience…” (p. 227) I confess that I took it for granted that this was a classic arrangement, but of course I can’t think of an example that precedes Chaucer. This is my favorite part of the book, because it drew me back into the tales themselves (which is why it took so long to get these questions to you). I’ll step back and let you elaborate on the brilliance and freshness of this structure, if it please you!

A: Tale-collections were common in the Middle Ages, but the premise was always that they contained one kind of tale: saints’ lives in this collection, comic fables in that one. And they were pretty much targeted toward a uniform sort of reader: devout laypersons for vernacular saints’ lives, noble patrons for arts of rule. Even Boccaccio’s Decameron, the closest precedent to Chaucer’s poem, strives for a kind of evenness in subject matter and delivery, nouvelles told in a kind of agreeable middle style by a socially-uniform group of gentlefolk. Whereas Chaucer mixes it all up: the different kinds of tales, and the socially varied group of Pilgrims who tell them. It’s not likely that any group as varied as Chaucer’s Pilgrims would have assembled in real life, but that’s how he wants it: the broadest imaginable collection of English folk, enjoying the widest imaginable collection of tale-types. It’s more a vision than a demographic or descriptive likelihood, but a wholly uplifting–perhaps irreplaceable–vision. The Pilgrims have their quarrels and problems but they work them out and stay on the road together. Still a pertinent message, I should think.

Q: What did you enjoy most about writing this book?

A: Working with the Chaucer Life-Records. All 494 known records of Chaucer’s life have been published and are easily available, but even professional Chaucerians don’t usually spend a lot of time on them. Whereas I feel that almost every little scrap–a reimbursement, a reward, a trip taken, a passport, a lawsuit, a legal testimony–invites narration, bristles with narrative potentiality. So I wanted the book to be evidence-based, and I wanted the reader to share my sense of discovery, of those bits and fragments from which a life-story gets assembled. Biographers sometimes take it upon themselves to conceal the traces of their labor, to announce conclusions about their subjects without lingering over the bits of evidence and the interpretative processes that got them there. I guess I wanted my readers to see the work being done, so they’d see how I got there.

Q: This book feels like a natural extension or sequel to Social Chaucer. Do you see it that way?

A: It, like my earlier Social Chaucer, cares about history, but in a different way. In Social Chaucer and in books like Hochon’s Arrow I let myself linger over the uncertainties of my evidence, over its recesses, its obtuseness, its silences and evasions. But when you’re writing a biography–even a “microbiography” as my publisher calls it–you have to commit to narrative. You can’t endlessly wobble about, was it this way or that way. You have to go ahead and make your best choice and get the story told. And I don’t mind that. It’s a different way of knowing. Narrative–the arrangement of details into a coherent account–is itself a powerful tool of discovery. When you narrate incidents, configure them or string them together, you learn things. One friend who read my book said, “Oh, the Canterbury Tales was exile writing.” That hadn’t occurred to me at all, even when the book was written. But it’s there, in the narrative, something that narrative brings to light and allows you to see.

Thank you, Paul, and congratulations on the publication of Chaucer’s Tale!

December 16, 2014

Meeting a New Character

I’m surfacing after being immersed in getting to know a character who just might start off a new series. I thought I had her, and then she dove down beneath my awareness, leaving a wake that eroded much of what I’d written. What had happened? As I sat with questions questions questions, I caught a flash of movement out of the corner of my eye. A memory. An aspect of her life I had written, then rejected as too complicated. Another flash of movement. Not a memory this time, but a piece of clothing with deep significance. I began a scene in which she donned the clothing and discovered a secret about something I’d already written. Patience, deep listening, a willingness to let go of what didn’t fit and pick up what seemed to resonate, though I didn’t yet understand why. Piece by piece, step by step, I redid the chapters. That’s where I’ve been.

November 30, 2014

Some Engaging Narrative Histories

Until recently I’d never thought about writing historical novels as an extension of what is known as microhistory. Some examples of microhistory you might know are The Return of Martin Guerre by Natalie Zemon Davis (Harvard University Press, 1984) and Montaillou (Penguin reprint, 2002) by Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, two of my favorite such books. If you haven’t read them yet, I highly recommend them—the first recounts a 16th century case of identity theft, the second is about a village in southern France caught up in the Cathar heresy. In both books, the authors use the historical record to chronicle the lives of common folk in a moment of crisis or controversy. It’s not so different from the aim of a novelist writing about a particular moment in history, though perhaps we (novelists) are as likely to focus on the powerful as on the common folk. Even so, in essence where we diverge is in how we write the tale—the microhistorian stays with the facts, fleshing them out only insofar as there is evidence to do so; the historical novelist takes the facts and fashions a story connecting the dots, creating fictional characters to fill the void, adding depth to actual historic figures with educated guesses. In my crime novels, I fashion stories that I feel are plausible given my research, and though I do include some actual figures, most of my characters are my invention, using characteristics and often basic storylines and lifelines encountered in my research–so in these I diverge even more from the microhistories, and yet I feel a stronger kinship with the writers of the genre than when I’m writing about royalty and the royal court.

I’ve been thinking about this while reading a recent publication in this genre, A Poisoned Past: The Life and Times of Margarida de Portu, a Fourteenth-Century Accused Poisoner by Steven Bednarski (University of Toronto Press, 2014). I had the great good fortune to review it for the Medieval Feminist Forum. The story: On a fateful day in 1394, Johan Damponcii ate his breakfast in the company of his wife, friends, and servants, then went out to work in the fields, where he fell ill, stumbled home, withdrew to his bed, and died in mid-afternoon.  Almost immediately a rumor spread through the town (Manosque, Provence) that his young wife, Margarida de Portu, to whom Johan had been wed only a few months, had either poisoned him or killed him by sorcery. The rumor was spread by her in-laws, or, more specifically, her late husband’s half-brother Raymon Gauterii, a litigious citizen of Manosque who happened to be a notary. The book recounts not only the murder trial but the ongoing litigation between Raymon and Margarida; Raymon is quite the character, and Margarida a strong woman, a survivor. Or so it seems in this author’s interpretation of the records. What is special about this book (beyond a great story and fascinating background material) is that Steven Bednarski interrupts himself throughout the book “to interrogate how we know what we think we know about Margarida and her world…” and suggests how someone with a specific interest—perhaps in the history of law or gender history—might arrive at quite a different interpretation. (xvii) Novelists, historians–we all bring our own predilections to our interpretations of the historical record.

Almost immediately a rumor spread through the town (Manosque, Provence) that his young wife, Margarida de Portu, to whom Johan had been wed only a few months, had either poisoned him or killed him by sorcery. The rumor was spread by her in-laws, or, more specifically, her late husband’s half-brother Raymon Gauterii, a litigious citizen of Manosque who happened to be a notary. The book recounts not only the murder trial but the ongoing litigation between Raymon and Margarida; Raymon is quite the character, and Margarida a strong woman, a survivor. Or so it seems in this author’s interpretation of the records. What is special about this book (beyond a great story and fascinating background material) is that Steven Bednarski interrupts himself throughout the book “to interrogate how we know what we think we know about Margarida and her world…” and suggests how someone with a specific interest—perhaps in the history of law or gender history—might arrive at quite a different interpretation. (xvii) Novelists, historians–we all bring our own predilections to our interpretations of the historical record.

And all along the way Bednarski provides interesting facts. I’ll share one: although the Jewish physician brought in to testify regarding the cause of death concludes that that Johan had a bad heart, and as he found no evidence on the corpse of poisoning—swollen lips or tongue, swollen or protruding eyes—he concludes that Johan died not of poisoning but of a heart attack. However, he does not entirely exonerate Margarida. Concerning Margarida’s epilepsy, which, in that culture at that time was considered a curse sent by God, Vivas Josep explains that “Johan had married a tender virgin with whom, after two months, he still could not copulate because of her illness. He was, therefore, extremely worked up by his unspent passion. Since he could not have his way with Margarida, his lust generated in him an evil melancholy. His pent-up sexual passions accumulated and produced a Syncope, which turned his hot passion cold and singed him. Unhealthy humors formed and twisted around his heart, changing its complexion.” The bottom line: Johan’s sexual frustration led to tendrils of unhealthy humors that wrapped themselves around his heart and constricted. Johan died, literally, of a broken heart.” (47)

Raymon Gauterii failed to mention Margarida’s medical condition in his accusations, a condition that often left her quite debilitated. But the other witnesses filled in the details—the Jewish physician, the midwife, Raymon’s sisters, neighbors, the deceased’s servant. All of these villagers are wonderfully individual and their voices enliven the text. Can you tell I enjoyed this book?

So now you have three more books to add to your pile of to-be-read. Actually, I’m reading another book that could be classified a microhistory, Paul Strohm’s Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury (Viking 2014). It’s just out–and Paul’s graciously agreed to a Q&A on this blog. So watch this space!

November 27, 2014

On This Day of Thanksgiving

Here in the States we celebrate Thanksgiving Day on the last Thursday of November, pausing to count our blessings. I have so much to be grateful for, work to engage me, nature to inspire me, remarkable scholars to shine a light on a period of time that intrigues me, readers who enjoy my work, family and friends and colleagues (and a feline) who buoy my spirits and share my life, the witch hazel that has burst into tiny yellow blossoms outside my office window, and all of you who follow my blog or pop in from time to time. For all this and much much more, I am grateful.

I am grateful, too, for the books of PD James. As you know, I just spent a month or more savoring her book Talking About Detective Fiction, and learning this morning of her death I felt as if I were receiving the news of a beloved house guest’s demise. I’ve spent the past few hours reading the tributes popping up everywhere. I needn’t repeat them. But I’d like to share my favorite quote, one that echoes my own feelings about my work:

I think while I am alive, I shall write. There will be a time to stop writing but that will probably be when I come to a stop, too.

Thank you, all of you, for sharing the art of storytelling and the Middle Ages with me.

November 9, 2014

The Benefit of Feline Companionship

After a deadline push I always feel a bit at sea, at odds with myself, uncertain what to tackle next. I felt it when I sent off the final proofs of A Triple Knot in late winter, I feel it now having just send off a proposal for a new series, including 3 chapters of the first book.

the white rabbit outside my window is all about deadlines

I have two fairly immediate deadlines, a book review for the Medieval Feminist Forum (a wonderfully engaging microhistory about a poisoning case in medieval France–more about that in a later post) and an essay for a Random House site about how I begin a project. And then, of course, there are the two crime novels I’m writing, an Owen Archer and the first in the proposed new series. I’ve also neglected the annotated bibliography that will reside on this blog as a companion to my published novels, providing background material for those who would like to explore more about the history and/or for those teaching one of my novels in a class. So much to do!

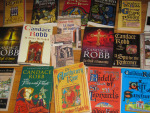

That’s the problem–too many choices. I was jumping from one to the next, accomplishing little other than creating chaos in my office. I’d made towering piles of books that are now threatening to slide off the top of my desk and the windowsill bookcases and spook my cat Ariel, who has just begun to spend time in my office, finally filling the void left by my beloved Agrippa. (She’s preferred the upstairs.) This is not the time for avalanches.

Fortunately, she took matters into her own hands this afternoon, settling on my lap while I was browsing in the first volume of The History of Parliament: The Commons 1386-1421 (J.S. Roskell, Linda Clark, Carole Rawcliffe, Alan Sutton 1992). I resolved to sit still as long as she wished–else she might not do it again. My reading extended a bit over 1 1/2 hours, during which time I read the introductory material and the specific background on York, all of which provided helpful insight into York politics in Owen and Lucie’s time as well as at the turn of the century (14th-15th), which is the period in which I open the proposed series. What a gift Ariel presented me–focus, stillness. After she departed, I pulled out my notes on both novels and added the insights I’d gleaned. Now to arrange the piles on bookshelves so that they won’t disrupt Ariel’s sleep. A good afternoon’s work.

Fortunately, she took matters into her own hands this afternoon, settling on my lap while I was browsing in the first volume of The History of Parliament: The Commons 1386-1421 (J.S. Roskell, Linda Clark, Carole Rawcliffe, Alan Sutton 1992). I resolved to sit still as long as she wished–else she might not do it again. My reading extended a bit over 1 1/2 hours, during which time I read the introductory material and the specific background on York, all of which provided helpful insight into York politics in Owen and Lucie’s time as well as at the turn of the century (14th-15th), which is the period in which I open the proposed series. What a gift Ariel presented me–focus, stillness. After she departed, I pulled out my notes on both novels and added the insights I’d gleaned. Now to arrange the piles on bookshelves so that they won’t disrupt Ariel’s sleep. A good afternoon’s work.

November 2, 2014

More Thoughts on Detective Fiction

I have been reading and thinking about PD James’s little book, Talking About Detective Fiction (Knopf 2009) while putting together a proposal for a new crime series. I feel as if she’s been my companion through this process, my reactions to her observations revealing my own preferences. But alas, I’ve used up all the renewals at the local library, and must return the book tomorrow. So I wanted to share some of the passages I particularly enjoyed, the one relating to her own choices.

Talking about point of view, she says: “My own choice of viewpoint is partly authorial, a detached recorder of events, and partly to move into the minds of the different characters, seeing with their eyes, expressing their emotions, hearing their words. …This for me makes a novel more complex and interesting [than first person], and can also have a note of irony as this shifting viewpoint can show how differently we can all perceive the same event.” (149-50) I, too, choose multiple points of view for much the same reasons. However, I seldom (if ever?) use “authorial, a detached recorder of events”; perhaps occasionally to give an overview of the setting. But ever since I realized that as a reader I often skip over long descriptions unless I’m learning something about a character, I tend to describe the setting from a character’s point of view. My preference, certainly not a RULE.

In the same chapter James describes how she went about choosing her main character. I didn’t find that helpful because my main characters choose me. But I did enjoy what she had to say about “the other characters, particularly the victim and the unfortunate suspects”: “If we do not care, or indeed to some extent empathise with the victim, it surely hardly matters to us whether he lives or dies. The victim is the catalyst at the heart of the novel and he dies because of who he is, what he is and where he is, and the destructive power he exercises, acknowledged or secret, over the life of at least one desperate enemy. His voice may be stilled for most of the novel, his testimony given in the voices of others, by the detritus he leaves…, but for the reader, at least in thought, he must be powerfully alive. Murder is the unique crime, and its investigation tears down the privacy of both the living and the dead. It is this study of human beings under the stress of this self-revelatory probing which for a writer is one of the chief attractions of the genre.” (153-54) Yes! I love the passage , but particularly the part I’ve italicized at the end. This is precisely what engages me, watching the community squirm. And always I want to remember the victim, that what is at stake is not only the danger that the murderer will strike again, but also that the murderer will escape punishment. I find it fascinating that she considers five suspects unwieldy—not that I disagree, but I’ve never counted.

I laughed when I read the following, wholeheartedly agreeing: “…however well I  think I know my characters, they reveal themselves more clearly during the writing of the book, so that at the end, however carefully and intricately the work is plotted, I never get exactly the novel I planned. It feels, indeed, as if the characters and everything that happens to them exists in some limbo of the imagination, so that what I am doing is not inventing them but getting in touch with them and putting their story down in black and white, a process of revelation, not of creation.” (157-58) When my characters begin to act up, I relax. Now I’m in play.

think I know my characters, they reveal themselves more clearly during the writing of the book, so that at the end, however carefully and intricately the work is plotted, I never get exactly the novel I planned. It feels, indeed, as if the characters and everything that happens to them exists in some limbo of the imagination, so that what I am doing is not inventing them but getting in touch with them and putting their story down in black and white, a process of revelation, not of creation.” (157-58) When my characters begin to act up, I relax. Now I’m in play.

And lastly, I appreciated this summation: “Murder is a contaminating crime and no life which comes into close touch with it remains unaltered. The detective story is the novel of reason and justice, but it can affirm only the fallible justice of human beings, and the truth it celebrates can never be the whole truth any more than it is in a court of law.” I think of the characters in my novels as poignantly, tragically human, even the murderers. They are all contaminated by the violence of the crime.

And yet I don’t find the writing of murder mysteries depressing. In fact, I find them more optimistic than the historical novels I’ve been writing. I think it’s because the continuing characters are, for the most part, safe at the end of the story. I can create loving relationships for them, and much joy. I didn’t have that power with Alice Perrers or Joan of Kent.

Much to ponder, from a writer I admire. As always, your thoughts are welcome.

October 29, 2014

Evolving Characters in a Series

As I line up a cast of characters with whom I will live for years to come if this new series is a go, I am paying close attention to what seem to be my rules of thumb for a mystery series. I’ve also been slowly reading P D James on the detective novel (Talking About Detective Fiction)and articles/interviews with other crime authors. I’m curious whether we agree on anything. So far it seems we don’t agree on much. I wrote in another post about PD James’s comment that few crime writers age their series characters.

Here’s a comment that surprised me, in an excerpt from a Publishers Weekly interview with Alexander Campion [no relation to my less-murderous alter-ego]: “There’s a trick to writing stock figure books. First off, nobody evolves.” Hang on, hang on, what?! Nobody evolves?!

Brother Michaelo is interesting to me because of the gradual changes in his character. Margaret Kerr matures over the course of her trilogy. Owen changes over time, as do Archbishop Thoresby, Alisoun Ffulford, Jasper de Melton…. I can’t imagine spending years with static characters. How tedious!

That’s not to say Alexander’s wrong. That’s his rule of thumb, and it works for him.

As for me, my characters evolve as I write them. Just this afternoon a character I had envisioned as blandly pleasant smirked on her first appearance. I don’t know how it happened. But when I reread what I’d written (or she’d written?), I realized it was better this way. Yes. She’s a bit irritating. She evolved right before my eyes, beneath my fingertips. I love unruly characters!