Helen J. Nicholson's Blog, page 5

December 11, 2016

A small plug:

September 16, 2016

At the start of term …

Trying to sort out all sorts of administration at once, I came across this document that I produced in around AD 2000 when I was examinations officer in History & Welsh History at this University (I’m now chair of the examination board). Most of these are genuine, and many have my heartfelt sympathy, but a few …

Twenty-two reasons why my examination papers aren’t ready yet:

I’m too busy filling in applications for research money.

I’ve been too busy writing my next book but one.

The papers are being translated into Welsh.

I’m moving house.

I forgot.

It’s half term and I have to look after my school-age children [note: this was from a male colleague].

My hamster died.

The papers have been translated into Welsh but the external examiner wants them amending to the dialect of Llanfihangel y Creuddyn.

I can’t be bothered.

Oh no is it that time of year already?

I’ve just moved house and I’ve been waiting for my bed to be delivered.

I’m in Birmingham.

I can’t remember how many questions I need to set.

What did I set last year?

I’ve just been converted to NT and I can’t get the printer to work.

I’m at home.

The external examiner wants all the double quotes changing to single quotes.

I’ve just moved house and I’ve been waiting for my desk to be delivered.

The external examiner wants me to rewrite my course.

One of the contributors to the paper is off sick for a fortnight.

I’ve broken my wrist ice skating.

My wife’s just had a baby [before the days of paternity leave, folks!]

And, Helen, while you’re on the subject, can you find out for me:

How can I get the exam papers printed in glorious technicolour?

Why does the university rubric say that the maximum mark for the paper is 100%?

Can the students take the text book into the examination?

When do the exam office want details of courses assessed by course work only?

Who is the external examiner? … Who’s s/he?

Can we have an extension on the submission of examination papers?

Can we go somewhere else for the external examiners’ dinner this year?

And, next year, can you remember:

Three students want to take their examinations in Patagonian Greek.

The external examiners want to see the last three years’ past papers.

I need six months’ notice of the final submission date for the examination papers.

I want you to write my exam papers for me …

August 23, 2016

Conference in Honour of Denys Pringle 17-18 September 2016: Conference Details and Registration

This link can be reluctant to work …

Visit the post for more.

Source: Conference Details and Registration

August 16, 2016

The Everyday Life of the Templars

… has now been cut down to the length required by the publishers. The material I’ve cut out will appear in an article I am due to submit for a Festschrift — the deadline for submission is the end of this month, so I’d better get on with it!

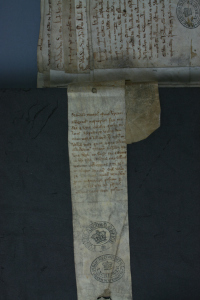

Random photo of possible relevance: The National Archives E 142/119 m 1d– debts due to the Templars

July 29, 2016

Book update

Some readers will know that during my Research Leave I have been working on a book-length study of the ‘Knights Templar estates’ material, The Everyday Life of the Templars, for Fonthill Media: http://fonthillmedia.com/. The book is due for submission at the end of this year.

The first draft of the book is complete, but it’s too long! So I am trying to shorten it, which is proving difficult.

July 22, 2016

Sheep may not safely graze

The Templars’ estates in Oxfordshire apparently had a problem of a shortage of pasture for sheep. Thomas Danvers’ accounts for the first few months after the Templars were arrested (January to May 1308) note the sale of two hundred wethers at Bradwell ‘which were accustomed to be sent to Guiting in Gloucestershire at Hokeday because of the default of pasture’; while he sold 41 lambs at Merton ‘on account of default of pasture’.

Oxfordshire had its quirks. So far it is the only county I have found where the Templars kept mules as a major source of motive power: there were fourteen at Cowley and Horspath, eight at Merton and two at Sibford. They also kept the usual horses, affers and oxen, but so many mules was unusual. Elsewhere in England and Wales there was one mule at Dinsley in Hertfordshire and one at Balsall in Warwickshire. The manor of Sibford in Oxfordshire did not produce wheat, which was very unusual for the estates that the Templars managed directly: the only other such estates that I have identified so far were Haddiscoe (Norfolk) and Togrind (Norfolk/Suffolk border).

Most of the Oxfordshire manors kept sheep — but not the commandery at Sandford. The only sheep here was a multo domesticus — a tame wether. Appropriately for a house by the Thames, Sandford also kept swans.

(Source: The National Archives, E 358/19 rot. 26-26 dorse; E 142/13 mem. 14).

July 20, 2016

The State of Crusade Studies: An Interview with Dr. Helen J. Nicholson

Among modern crusade historians, few are as respected as Helen J. Nicholson. Indeed, as Professor of Medieval History at Cardiff University, where she has taught for more than twenty years and serv…

Source: The State of Crusade Studies: An Interview with Dr. Helen J. Nicholson

June 17, 2016

The Crusade of Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury

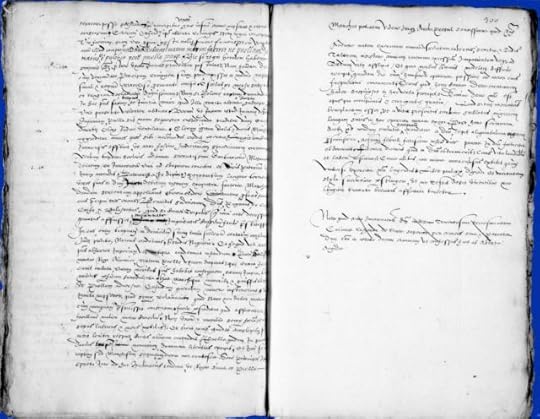

One of the five manuscripts of the so-called Itinerarium Peregrinorum 1: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale MS lat 6044 fols 299-300: from Gallica.bnf.fr

At the SSCLE conference the week after next I’ll be speaking about an old friend, the Itinerarium peregrinorum, which some readers will remember I translated many years ago (published as Chronicle of the Third Crusade). The anonymous author of the so-called ‘Itinerarium peregrinorum 1′ showed a particular interest in Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury’s deeds at the siege of Acre between his arrival at Acre 12 October 1190 and his death on 19 November. The obvious suggestion is that the anonymous author was one of the archbishop’s entourage. But who was in his entourage? Has anyone made a study of the archbishop’s crusading expedition of 1189-90?

So far the best candidate is the archbishop’s chaplain, who wrote to the convent of Canterbury in October 1190 with news of the siege: his description of the siege is very like that in IP 1.

May 13, 2016

Templar chapels were just full of … chapel stuff.

National Geographic news online has an article today about one modern Templar myth. The author, Betty Little, consulted me on the Templars just as I was up to my ears in inventories of Templar chapels, hence the tone of my comments on the Templars’ religious beliefs.

For anyone who wants more, here are a few chapel inventories!

Temple Newsam, Yorkshire: The chapel contained a missal (containing the service of the Mass), two legendaries (books of lives of the saints), a book of antiphons (sung texts), two psalters (books of psalms for liturgical use), a gradual (choir-book), an ordinal (setting out the priest’s movements during the Mass) and an epistolary (readings from New Testament books), two sets of vestments, a tunic, three albs (long white vestments worn by the priest), six towels for the altar and a chalice worth sixty shillings (three pounds) (TNA: E 142/18 mem. 7).

[Before we go any further: for details of liturgical books see the British Library’s online guide ‘Liturgical manuscripts – Books for the Mass’ at https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/TourLitMass.asp (liturgical books) and https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/TourLitMass.asp (books for the Divine Office).]

Faxfleet, Yorkshire: In the chapel there were five sets of vestments, a chalice, two silver phials, two missals, a legendary, two books of antiphons, two psalters, two graduals, two books of tropes, a martyrology (narratives of the lives and martyrdoms of the saints), a book of collects (short prayers), an ordinal and ‘placebo’ or office for the dead; two surplices, two towels and a towel for the sacraments, and a pyx ‘for the body of Christ’, or consecrated wafers (TNA: E 142/18 mem. 13).

Moving to France: at the Templars’ house at Arles there was a considerable number of books – liturgical books, sermons, calendaria or calendars of saints days, a copy of the Rule of St Augustine, a book of Gospels, a book of Biblical commentaries, and volumes of ‘institutes’, which could have been copies of the Templars’ rule and statutes – as well as much valuable plate, priestly vestments, candlesticks, bells and chalices. (For a complete list, see Damien Carraz, ‘L’emprise économique d’une commanderie urbaine: l’ordre du Temple à Arles en 1308’, in Économie templière en Occident: Patrimoines, commerce, finances, ed. Arnold Baudin, Ghislain Brunel and Nicolas Dohrmann (Langres: Dominique Guéniot, 2013), pp. 141-75, at pp. 173-5.)

The chapel at Baugy in Normandy contained four pairs of vestments, a chalice, the ‘books of the chapel’, cloths and altar ornaments. At Bretteville there was a chalice, some liturgical books (one missal or mass book in good condition, two in pieces, a two-volume breviary, a psalter and a gradual), three vestments for the priest and four altar cloths. The breviary at Corval was also in two pieces: there was also a missal, a gradual, a book of antiphons and a psalter, with a chalice, two pairs of vestments, eight fragments of candle, two boxes de ylbire (ivory?), a copper stoup or basin for holy water, a censer and a leather cape. At Voismer the chapel equipment was similar: a chalice, three pairs of vestments, and a range of liturgical books: a psalter, gradual and missal and two large livres deu temporal – a ‘temporal’ set out the feasts of the liturgical year related to Christ’s life. (For these Norman inventories see Léopold Delisle, ed., ‘Inventaire du mobilier des Templiers du baillage de Caen’, in Études sur la condition de la classe agricole et létat de l’agriculture en Normandie en moyen-âge (Paris: Honoré Champion, 1903), pp. 722, 724, 725, 727, translated by Malcolm Barber and Keith Bate, The Templars: sources translated and annotated (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), pp. 193, 195, 197, 199.)

The Templars’ Irish houses were similarly equipped: at Cooley in County Louth there was a chalice worth ten shillings, various liturgical books including a calendarium, cloths and towels; while at Kilsaran in the same county there were liturgical books including part of a book de lege scripta (of written law: perhaps the Templars’ rule?), a very small ivory image of the Blessed Mary, a gilded chalice, vestments, cloths and a tin or pewter cruet, and two bells, one big and one little. Kilcloggan’s chapel (County Wexford) had the usual liturgical books and a martyrology (a narrative of the lives of saints), a chalice and vestments, while the church also had a chalice, liturgical books ‘and other tiny books worth four shillings’. At Clontarf there was a ‘book of the gospels and the Brut of England written in French (presumably a French version of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s history of the kings of Britain), worth one mark’ as well as a missal, vestments, two chalices and other plate (see G. MacNiocaill, ed., ‘Documents Relating to the Suppression of the Templars in Ireland’, Analecta Hibernica, 24 (1967), 183-226 at 191, 195, 200, 202, 215).

Back to England: at the Templars’ chapel at Dinsley (Hertfordshire), where the English Templars held their annual chapter meetings, the sheriff found a breviary, an antiphoner, a missal, a psalter, troper or book of tropes, a service-book, a martyrology, a chalice, four copes worn in choir, a lenten veil with fittings, and two worn-out vestments (TNA E 358/19 rot. 52).

The contents of the Templars’ chapel at Temple Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire included a ‘tabula’ (a wooden panel or board) with holy relics in it, and a silver gilt thurible or censer. When the Templars were arrested in January 1308 and their property was valued by the sheriff of Bucks., Gilbert of Holm, the reliquary-panel and the silver censer were put to one side. The king instructed Gilbert to hand these valuable items over to the keeper of his wardrobe, Ingelard of Warle, and Ingelard was told to put them in the king’s chapel.(TNA E 358/18 rot. 6 dorse. )

The Templars’ chapel at Sandford in Oxfordshire had the usual liturgical books including a portable breviary of St Edmund and a legendary of the common saints, a temporal, two psalters, two tropers for the mass of the Blessed Virgin and an ordinal. There were two silver chalices, two crosses, an incense-boat, four pairs of vestments, four copes, a tunic and a dalmatic, six surplices, three rochets or gowns, three pairs of corporals, three cushions, a phylactory or reliquary, ten consecrated towels, two altar frontals, a baudekin – a piece of rich embroidered cloth – four banners, four towels ‘of diverse work’, two amices (vestments), a pair of organs, four cruets, a lead basin for holy water and a pair of ferra pro oblationibus, presumably ‘obley-irons’ for making the eucharistic hosts (TNA: E 142/13 mem. 3).

The nearby chapel at Bisham in Berkshire was even more richly equipped. The liturgical books included antiphoners, a legendary in two volumes, an ordinal, gradual, processionals, an office of the Blessed Mary, collects and other volumes; there were also two silver gilt chalices, vestments, tunics embroidered with silk, altar frontals, two in silk; a pair of corporals, towels for the altar of the Blessed Mary and cloths of silk with golden stripes and in red silk for holding the paten, among others. There was a silvered image of the Blessed Mary, a silver censer, and various relics, candlesticks, processional banners and crosses, tapets (hangings or carpets), a metal vessel for holy water, an organ, two large bells and a golden cloth ‘which is called Damaskyne’ (TNA: E 142/13 mem. 9 verso).

The inventory of the ‘great church of the Temple’ at New Temple in London taken in January 1308 lists a series of silver items: chalice, two thuribles, two phials or cruets, two basins, and a ciphus (bowl or cup) for the host; there was a copper ‘boat’ for incense with a silver spoon, an ivory pyx or casket for the host, a pewter ‘chrimatory’ (a container for consecrated oil), a metal cross with a banner, a silver base for a cross, a missal and a silver text containing the gospel readings for the whole year, six pairs of vestments with tunic and dalmatic and one without, a pair of albs and amices for deacons, and two pairs for boys; two offertory cloths for holding the paten (the dish on which the host was placed), two rochets, a pair of corporals (a piece of linen placed on the altar during the service), a towel and an altar cloth, an altar frontal, five tapets to go in front of the high altar, two choir capes, two candlesticks of Limoges work (de copere de Lymoges) for processional candles, six metal candlesticks before the high altar, two pairs of organs, an iron candlestick and two further tapets …

The inventory for New Temple goes on and on: you can read the whole thing in translation in T. Henry Baylis, The Temple Church and Chapel of St Ann, etc., An Historical Record and Guide (London: George Philip and Son, 1893), pp. 141-5: the originals are at TNA: E 358/18 rot. 7(1-2) and E 358/20, rot. 3.

May 12, 2016

Updates

After looking at the 1308 accounts for Temple Guiting in Gloucestershire, I’ve updated my posts on the Templars’ charitable giving and on women workers on Templars’ estates. I’ve also found some more Peacocks.