Michael Pryor's Blog, page 19

August 27, 2012

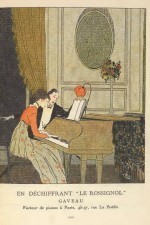

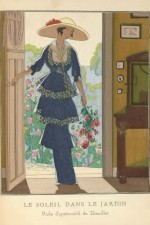

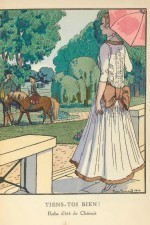

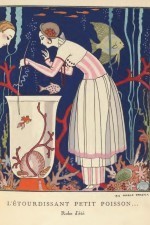

La Gazette du Bon Ton 1

I’ve been promising this for a while. It’s one of the things I stumbled across in my researching. How I love serendipity.

La Gazette du Bon Ton was essentially what we’d call today a fashion/lifestyle magazine. It was published in Paris from 1912 to 1925, and offered a limpid glimpse of the world of the upper class French, with utmost style, taste and refinement. The most distinctive aspect was the illustrations, which were splendidly rich and elegant. Noted illustrators and artists featured their works in the pages of this journal, people such as Bernard Boutet de Monvel, Georges Lepape, Georges Barbier and Pierre Brissaud and their depictions of the fashions from the most haute of haute couture houses is the last word in chic. The incidental detail in these illustrations are a goldmine for a writer, too, with furniture, transport and architecture providing a backdrop for some of the most attractive gowns and suits imaginable.

I’m gradually putting together a selection of some of the best of these illustrations. Here’s the first selection, with more to come in future. Click on each thumbnail for the full file.

Writers Write: My Favourite Book 31

Hidden somewhere in one of the cupboards, I have a small cross-stitched sampler hand-embroidered (and designed) by a friend when we were both 14 or so. It’s in Elvish. I also own the Donald Swann record of the poems and songs of Middle-Earth, which includes J.R.R Tolkien reading “A Elbereth Gilthoniel”. I suspect that I can still recite most of the words. I can certainly still dredge obscure Middle-Earth facts out of long-unused areas of my memory – for example, that Elrond is Galadriel’s son-in-law.

Yes, I’m a Lord of the Rings tragic. I don’t dare open the books, or I wouldn’t get anything else done until I finished rereading them yet again. The trilogy has (almost) everything: humour, deep history, high drama, languages, mysterious forms of magic, romance (albeit rather chaste), relentless villains, flawed heroes – even dragons and Elves. And I always did like it that they’re not just elves, but Elves.

I know that people either love or hate the trilogy, so that’s as far as I’ll go in trying to convince anyone of the virtues of LOTR (though I can’t resist pointing out that the prose is a delight, nothing like the debased Quoth that so many insist it is; archaic language is only ever used when it’s appropriate and even necessary, usually in scenes involving characters who have outlived many generations of human beings – even if they still look young, or at least ageless.)

LOTR was a perfect fit for the teenage me: a fey budding poet obsessed with ancient languages and Faery, a misfit in one of the roughest High Schools in the Hunter Valley, where surfies ruled and netball was brutal. What could have been better than a trilogy that grew out of a philological obsession with the deep myth/historical background to a set of invented languages? With Elves?

Jenny Blackford’s most recent book is The Priestess and the Slave, 2009, Hadley Rille Books (http://www.hadleyrillebooks.com/priestess.html). For more, see Jenny’s website or her blog.

August 13, 2012

August 5, 2012

A new Laws of Magic idea

I’m playing around with writing an adult novel – ‘The Laws of Magic’ ten years on. Aubrey, Caroline, George and Sophie in a  world startlingly like our own in the Jazz Age, but with magic. Now, I don’t know if this has been done before at all, taking a YA novel and its characters and leaping forward into the adult world.

world startlingly like our own in the Jazz Age, but with magic. Now, I don’t know if this has been done before at all, taking a YA novel and its characters and leaping forward into the adult world.

I think it has possibilities.

July 25, 2012

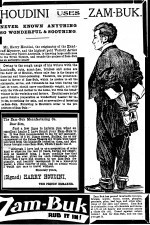

Soothing the Savage Magician

The life of a professional magician isn’t always easy. There’s the death-defying, the hair’s breadth escapes, the daring what ordinary mortals would not. And then there’s the problem of skin care.

Harry Houdini toured Australia in 1910. A tireless self-promoter, he embarked on a series of stunts to publicise his performances, including being wrapped in chains and hurling himself from Melbourne’s Princes Bridge into the Yarra River. Various members of the public set challenges as well, with fiendishly difficult rope entanglements, hand-built coffins and manacles of devilish devise.

With all this, it’s no wonder that Houdini appreciated a ‘healing embrocation’, especially for those wrists chafed during his handcuff escapes. An obvious aficionado of soft and supple skin, Houdini penned a testimonial to the makers of Zam-Buk, an ointment which promised to heal ‘cuts, bruises, scalds, burns, eczema, pimples, psoriasis, piles, bad legs and other affections of the skin and tissues’.

It’s good to know that even masters of mysteries like Houdini need to take care of life’s niceties.

July 24, 2012

Melbourne Writers’ Festival Schedule

And here’s my Melbourne Writers’ Festival schedule:

And here’s my Melbourne Writers’ Festival schedule:

Sunday 26 Aug 2012 3.00 pm – World Creation: How to Write Fantasy the Professional Way (workshop)

Monday 27 Aug 2012 11.15 am – A Beginner’s Guide to Steampunk

Wednesday 29 Aug 2012 10.00 am - 10 Futures

Thursday 30 Aug 2012 at 01.45 pm – Getting Started & Write Across Victoria

For bookings and more details, go to the .

Needless to say, I’m looking forward to it.

July 23, 2012

My Favourite Cultural Experiences

A few months ago, I was at the Radio National Melbourne studio and recorded a spot where I reflect on my five most memorable cultural experiences. It was aired yesterday and you can get the podcast here.

A few months ago, I was at the Radio National Melbourne studio and recorded a spot where I reflect on my five most memorable cultural experiences. It was aired yesterday and you can get the podcast here.

July 18, 2012

Writers Write: My Favourite Book 30

The book that haunted my childhood was Elidor by British writer Alan Garner. An icy, grief-stricken story overshadowed by the twilight feel of Celtic myth, it was a short sharp shock after the cosiness of the Narnia tales I knew and loved. Elidor was the first book to shatter my childhood expectations of happy endings, to unsettle me with the power of elision and loss. Garner, an elusive writer considered among the greatest fantasy writers, experiments with how much of plot and character he can pare away and still have a story standing. My childhood copy of Elidor, (the Fontana Lions edition illustrated by Charles Keeping) which I still own and treasure clocks in at a bare 160 pages.

Set in the bombed, rubble-strewn streets of post-war Manchester, Elidor is the perfect post-war British fantasy evoking exquisitely so much that has been destroyed, that has vanished forever.

Four siblings, Nicholas, David, Helen and Roland Watson, are drifting around central Manchester. Children of a different era, they are without money (or mobile phones, of course) or adult supervision. Their family is moving house and, banished out of the way by their parents, they are searching for something to do. They find their steps seemingly directed to a street where houses and a church are being demolished. The bombed church is the gateway through which the children find themselves in Elidor, the Green Isle of the Shadow of the Stars.

But Elidor is no Magic Faraway Tree or Narnia, a place of exhilarating adventure. Elidor is dying. Like Manchester, it has been attacked by faceless evil. Malebron, its wounded king seemingly without an army or any subjects, turns, inappropriately, to the four bewildered children for help. Like the beleaguered adults in the real world who were forced to fight World War Two, he is unable to shield the children from the harsh reality of war or even to explain it.

‘The darkness grew,’ said Malebron. ‘It is always there. We did not watch, and the power of night closed on Elidor. We had so much of ease that we did not mark the signs – a crop blighted, a spring failed, a man killed. Then it was too late – war, and siege, and betrayal, and the dying of the light.’

This is no explanation at all, despite the echo of Dylan Thomas in the last line, but it is all the explanation for evil that any of us are ever likely to get.

Roland, the youngest of the children and derided for his dreaminess finds that in Elidor his imaginative power is ‘real as swords’ and so the heaviest burden of saving Elidor falls on him. The novel’s epigraph, Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower came, is a line from King Lear, which refers to a fairytale in which Childe Rowland rescues his sister, Burd Ellen, from the King of Elf-land. In the novel, each child is encumbered with a treasure – a stone, a spear, a sword and a cauldron. Malebron insists the children must protect the treasures in our world in order to keep Elidor alive while they, and all Elidor, wait for the mysterious Findhorn who alone can save the land.

When I first read Elidor, at around age seven or eight, I was baffled and haunted by its spareness. It was my first experience of how restraint hooks the reader. I wanted to know more. I needed to know more: more about Elidor, about the evil Mound of Vandwy, about the magical Findhorn. In negative reviews of Elidor readers voice exactly these complaints. Elidor is too spare, too mysterious, the reader spends too little time there. It’s true that Elidor is not The Lord of the Rings. Garner doesn’t give us a whole other reality to luxuriate in. We search the book for the world hidden behind and within the words and this obsessive search ensures that many sentences in the book become burned into the mind. These complaints about Elidor illustrate how brilliant the story is and how the writing subverts the idea of fantasy as escape.

It was the collision of the other world of Elidor with (relatively) modern Manchester that excited me so as a child. Garner did his science homework and the scenes using electricity as the analogue of Elidor’s magic in our own world are the most frightening. The framing story for Narnia was set in a past that to me as a child was almost as remote as the Middle Ages. The Lord of the Rings is of course an entirely other world, one in which technology has not entered the industrial age (though the portrayal of Isengard does seem to be a critique of the Industrial Revolution).

To see Elidor invade the world I recognised, where children watched television while they did their homework, was to experience the most potent fantasy, in which wonder and horror stalk the domestic, the ordinary, the everyday. Writing this now, I realise that Elidor has been one of the most powerful influences on my own work, that I too am most interested in writing about the reality we know, here and now, but a reality spiked with unexpected shards of beauty and horror.

The end of Elidor is perfect, devastating. Like The Lord of the Rings, and unlike so much heroic fantasy, Elidor shows the hollowness of victory, the price of trying to make whole that which can never be restored. Elidor resonates in an adult register; you may defeat the darkness but the price will be higher than you can bear.

Helen mended the jug she had found in the hole. It was a large pitcher, and it had broken into five pieces. She spent hours glueing them together, almost in tears when she thought of what she had done. The pitcher had lain in the ground such a long time, and such a little care would have saved it. Now she was too late, and nothing could make it whole again.

Claire’s novel ‘When We Have Wings’ was published by Allen & Unwin in July 2011 and shortlisted for the 2012 Barbara Jefferis Award. It is also being published in Spain, Portugal, The Netherlands and Russia and has just been released as an audiobook by Bolinda Publishing. For more, visit Claire’s website.

Claire has also just announced a giveaway happening on GoodReads until August 31st. Be in it!

July 16, 2012

Mandarin Chocolate Cake (by request)

I’ve had so many requests for the recipe for this one, I thought I’d put it up here.

Ingredients:

250g dark chocolate

250g unsalted butter

6 eggs, separated

½ cup caster sugar

3 tablespoons plain flour, sifted

¼ cup almond meal

1 tablespoon mandarin zest

Preheat oven to 190 deg. Melt chocolate and butter in heatproof bowl over saucepan of simmering water or microwve. Stir until just melted. Remove from heat and set aside.

Lightly mix egg yolks and sugar. Gradually add melted chocolate to egg mixture, stirring constantly. Using a large metal spoon, fold through the flour, almond meal and zest.

Whisk egg white until stiff peaks form. Using large metal spoon, fold half egg whites through the batter until barely combined. Repeat with remaining whites.

Pour into 23cm greased springform cake tin and bake for 35 mins. Don’t worry if cake seems to be wet in the centre: it will firm up a little on cooling.

Remove from oven and leave to cool completely in tin. Transfer to a serving platter and dust with cocoa. Serve with mandarin slices and lightly whipped cream.

July 9, 2012

Dystopias – Why So Popular?

Why Dystopias?

I have two suggestions to explain the current popularity of dystopias/post-apocalyptic fiction, especially for teenagers. I understand that dystopic fiction and post-apocalyptic fiction are not necessarily the same thing, but they’re often conflated and I’ll settle for the combination term in this discussion.

Firstly, I’ll offer the historical precedent as an explanation: the popularity of dystopic fiction is a reflection of the anxieties of the time. One of the great flowerings of ‘end of the world’ fiction was in the 1950s, the stories that Brian Aldiss dubbed ‘the cosy catastrophe’, such as John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids (1951). Walter M Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1960) was anything but cosy, but its depiction of a post-nuclear holocaust world was also emblematic of the era. The readers at this time, of course, had just been through the Second World War an experience from which the end of the world was easily extrapolated. Added to this was the nuclear arms race where mass annihilation on a scale hitherto undreamed of was the talk of the day. Thinking the unthinkable was an everyday occurrence, and so stories where the world ended were simply capturing of the spirit of the times.

As well as documenting the fears of the times, these narratives were performing one of the fundamental purposes of story. If these anxieties are made into stories they become less frightening, more manageable. The vast, irrational horrors that are lurking on edges of the real world can be tamed by our imaginations and our nightmares given an outlet.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, in response to a growing awareness of the ecology, we had a steady stream of environmental apocalypses in fiction. Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room! (1966) was filmed as Soylent Green in 1973 and let Charlton Heston scream the immortal: ‘Soylent Green is people!’. John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar was an unforgettable ride through a world collapsing under our own numbers.

Given this, is it too long a bow to draw to suggest that the most popular dystopias in fiction today – where society has collapsed and is replaced by a savage, dog eat dog world with only the fittest surviving – is a reaction to the Global Financial Collapse and the teetering state of the international economy, bruited on news services as stridently and as tirelessly as the Red Menace doomsayers were in the late 1950s?

I don’t want to suggest some sort of crude, reductive, one to one correspondence here. The counter-claims abound. It’s well documented, for instance, that the Great Depression was a time when the fluffiest, frothiest, most escapist movie musicals were popular, when people wanted to dance all their cares away.

Still, in today’s 24 hour constant coverage of the state of the world, is it any wonder that this atmosphere of crisis, meltdown and disaster is a context from which dystopian/post-apocalyptic fiction has grown?

Secondly, I’ll suggest that dystopic fiction/post-apocalyptic fiction is particularly popular with Young Adults is because of the paradoxical liberation for teenage characters that comes about in these dystopian worlds. Traditional structures have collapsed or subverted, so teenagers aren’t controlled or ordered about, or coddled as they are in today’s beneficent society. Not only are teenagers allowed to be free from these restrictions, they don’t have anyone to rely on for their own survival. The independence they yearn for is thrust upon them, is inevitable if they are to survive. Yes, it’s terrible that civilisation has collapsed, but no-one’s going to be telling them they have to be in bed by 10 pm.

In some ways, this can be seen as a way of dealing with an age-old problem in writing YA fiction. When there’s a problem, why don’t the kids just call the police/get their parents to help/contact the authorities? This is particular challenge when writing YA Crime Fiction, and can lead to all sorts of contrived situations. It also results in the ‘dead parent’ syndrome in lots of contemporary YA fiction, where it seems as if the only way to explore a YA character taking charge of her own life is to remove the parents from the narrative completely. They’re dead, Jim.

A post-apocalyptic world, where all normal societal restraints are gone is a testing setting in which to place a YA character, to see whether she will cope on her own, how she will grow and what she will do when faced with challenges vastly removed from our comfortable day to day lives. In extreme situations, we can discover truths.

Call them dystopias, call them post-apocalyptic stories, their appeal is undeniable. Some of the appeal comes from the shudder at the futures presented, some of it from a sense of escapism into a world of danger and adventure. For many young readers, though, the end of the world is proving to be just the beginning …