Michael Pryor's Blog, page 14

December 19, 2013

Machine Wars Cover Reveal

And here it is: the superb, stylish, sensational cover of Machine Wars, my 33rd book, due in April from Random House Australia.

I love it!

December 12, 2013

‘Year’s Best’? Perhaps not …

It’s that time of the year again, and I’m not talking about the festive season. I’m talking about that end of year musing that gives us the parade of ‘Year’s Best Books’ lists or ‘Holiday Reading Guides’ that are starting to feature in the arts pages and corners of the online world.

I’m not talking about the festive season. I’m talking about that end of year musing that gives us the parade of ‘Year’s Best Books’ lists or ‘Holiday Reading Guides’ that are starting to feature in the arts pages and corners of the online world.

I must admit a certain weariness with which I contemplate these lists, for I’ve read them for years forlornly hoping that one of them, one day, would feature a genre title.

And by genre, I mean Fantasy and Science Fiction. Occasionally, the compilers of these lists let a Crime title creep in, probably because it lends the compiler a touch of raffishness, hinting that they could go out onto those mean streets if they needed to.

What I look for so vainly is a ‘Year’s Best’ list that understands that quality comes from all aspects of literature. Instead, I see repeated year after year a narrow, blinkered selection that excludes a wide and rewarding range of literature.

I’ll go out on the limb and guess that the compilers of these lists haven’t read lots of Fantasy and Science Fiction and then said to themselves, ‘Well, really, none of these measure up’. I stick my neck out and claim that they haven’t read any (or much at all) in these fields. It’s like they’ve eliminated these books from contention even before the contest has been announced.

They’re not even considered.

Yes, I know that I’m guessing and that I’m possibly traducing thousands of ‘Year’s Best’ list compilers, but my view has been formed after seeing decades where NO genre books have appeared on such lists.

So what we’re really getting is a list of the best books of the year selected from a narrow, pre-determined field that is deemed, ahead of time, as worthy of featuring on such a list.

For those naysayers out there who are rolling their eyes at my reasoned and articulate case, I’ll acknowledge that genre books do feature on some ‘Year’s Best’ lists – but they are the lists with a specific genre focus. Year’s Best SF. Year’s Best Fantasy. Year’s Best Horror. Places where they’re shuffled off to one side and neatly contained.

The best of these books should feature in every purported Year’s Best list, but they don’t.

Sour grapes? Much ado about nothing? Perhaps, but every time I see one of these lists it’s a not-so-subtle slap in the face to every writer and reader of genre fiction.

Of course, there are those who think that genre writers and readers deserve a slap in the face, but that’s another matter.

Yes, I’m probably being naïve in my suggestion that genre fiction should be included in these ephemeral lists. No serious reviewer would compromise her/his reputation by such an action. In fact, I’ve been so disappointed, over the years, that I’d crack a smile if Fantasy and Science Fiction were even considered for selection, let alone actually appearing. I’d count that as a win – of the small variety.

And here’s the point where I acknowledge that the sidelining of Fantasy and Science Fiction is shared by Romance, which suffers from the same blindness (or contempt?) that its speculative genre cousins do. I share your pain.

So, right now, I’m shining a spotlight on every compiler of a ‘Year’s Best Books’ list or a list of ‘The 10 Best Books of 2013’ or even ‘A Holiday Reading Guide’. Either consider and include genre titles (and wouldn’t it be a sight to see nine out of ten books on such as list as genre titles?) or rename your list as ‘Year’s Best Books From a Narrow and Pre-determined Selection’.

December 4, 2013

‘Think Ahead’ at Scienceworks

Scienceworks, Melbourne’s science museum, has just opened an amazing  new long-term exhibition called Think Ahead. The launch was on 4 December and I was lucky enough to be invited along because my association with this extraordinary project goes back to early 2013.

new long-term exhibition called Think Ahead. The launch was on 4 December and I was lucky enough to be invited along because my association with this extraordinary project goes back to early 2013.

Not long after 10 Futures was published, I had an email from Kate Phillips, an exhibition curator at Scienceworks. She let me know that Scienceworks was planning a major exhibition looking at the future. She was, naturally interested in 10 Futures and the process I’d gone through in putting it together. We email chatted and I shared some of the research sites and resources I’d used in my imaginings of the future.

Now, nearly two years later, Think Ahead is here in all its glory. It’s a marvellous exhibition, full of fun interactive activities and experiences ranging from robots to recycling to constructing your own virtual city to making yourself teleport Star Trek style.

On top of all this, I am a museum exhibit.

One of the features of Think Ahead is a number of listening posts, places where futurologists(!) muse about the where we’re going as a species. One of these esteemed prognosticators is Australian novelist, imagineer and thinker, Michael Pryor  .

.

Go and see Think Ahead and start imagining the future you want to make.

November 27, 2013

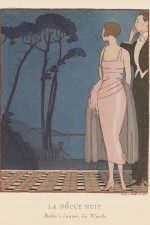

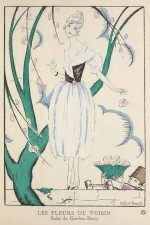

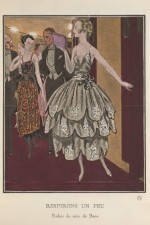

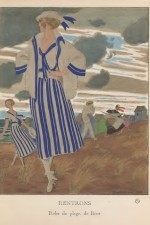

1920 Style and Elegance

Apropos of nothing in particular, here’s a selection from the glorious 1920 editions of La Gazette du Bon Ton. Style, elegance, grace, panache and whimsy.

November 21, 2013

Writing Advice from C.S. Lewis

On this fiftieth anniversary of the death of C.S. Lewis, I thought I’d bring some of his writing advice to you. This comes from a letter that Lewis sent to a young correspondent in 1956, but the suggestions are eternal.

Always try to use the language so

as to make quite clear what you mean and make sure y[ou]r. sentence couldn’t mean anything else.

as to make quite clear what you mean and make sure y[ou]r. sentence couldn’t mean anything else.Always prefer the plain direct word to the long, vague one. Don’t implement promises, but keep them.

Never use abstract nouns when concrete ones will do. If you mean “More people died” don’t say “Mortality rose.”

In writing. Don’t use adjectives which merely tell us how you want us to feel about the thing you are describing. I mean, instead of telling us a thing was “terrible,” describe it so that we’ll be terrified. Don’t say it was “delightful”; make us say “delightful” when we’ve read the description. You see, all those words (horrifying, wonderful, hideous, exquisite) are only like saying to your readers “Please will you do my job for me.”

Don’t use words too big for the subject. Don’t say “infinitely” when you mean “very”; otherwise you’ll have no word left when you want to talk about something really infinite.

Source: C.S. Lewis Letters to Children, ed. Lyle W Dorsett and Marjorie Lampmead, Collins London 1985.

November 14, 2013

Five Top Hard SF Books

I was inspired by Linda Nagata’s thoughtful article to write this one. Hard SF can be a hard sell. Of all the multifarious and diverse aspects of Science Fiction, Hard Science Fiction is the one most likely to get non-readers recoiling in horror. It’s the SF sub-genre most parodied, most vilified and most misunderstood.

Which is a shame because, as with most things, the best of it is superb. Hard SF discusses, foregrounds and takes seriously an aspect of modern life that is shamefully neglected in literary fiction: science and technology. If these feature in literary fiction today, it’s superficially or with, at best, a jaundiced eye.

As has been my wont with these recommended reading lists, I’ll foolishly venture a definition: Hard SF is the branch of Science Fiction where accurate representations or extrapolations of science and technology are vital to the story. It has many overlaps with Space Opera and other SF sub-genres, but fuzziness like that is part of the glory of genre definitions.

Ringworld – Larry Niven (1970)

Ringworld – Larry Niven (1970)One of the great Hard SF adventures, this rattling good yarn takes the notion of the alien artefact and runs with it, imagining an artificially constructed world that rings a sun. The world is nearly two million kilometres wide and has a diameter roughly that of Earth’s orbit around our sun. It’s a jaw-dropping conceit, and it’s just the backdrop for shipwreck story of monumental proportions. Great fun.

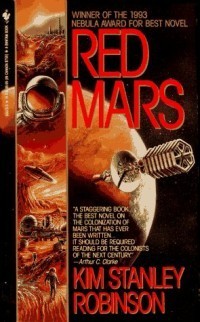

Red Mars – Kim Stanley Robinson (1993)

The first of a trilogy, this book is a rigorous exploration of exploration, where humanity is opening up Mars for colonisation. The technical, engineering challenges are foregrounded, but the ecological and the political are by no means ignored. Absorbing and ultimately moving.

Permutation City – Greg Egan (1994)

Permutation City – Greg Egan (1994)Australia’s own Greg Egan . It doesn’t get much harder than this, with quantum ontology, artificial intelligence and simulated reality just part of this onslaught of cutting edge concepts. It’s philosophical, abstract and dense. Tasty stuff.

Revelation Space – Alastair Reynolds (2000)

Space, with all of its unlimited possibilities. Lots of nanotechnology, human modification, and heavy spaceship engineering doesn’t overpower the character exploration and interaction, which is sharp and profound in this far future world.

U

p Against It – MJ Locke (2011)

p Against It – MJ Locke (2011)More nanotech in a society in our asteroid belt. The everyday difficulties of living in such a hostile environment are presented with verve and panache, with a rogue Artificial Intelligence thrown in for good measure. This is extrapolation of the best kind. It’s careful but creative with its prognostications and never forgets the importance of a strong narrative.

November 5, 2013

Measuring Your Fantasy World

A writer has many challenges when creating a consistent, self-sustaining fantasy world for a story. Some are easy to anticipate, but others sneak up on you. After months of preparation, mapping, outlining and imagining, many a Fantasy writer has leaped into the first draft intoxicated by the joy of the world she has created, only to be brought up short by something apparently minor which results in some ceiling gazing and mumbling things like, ‘I really hadn’t thought of that.’

when creating a consistent, self-sustaining fantasy world for a story. Some are easy to anticipate, but others sneak up on you. After months of preparation, mapping, outlining and imagining, many a Fantasy writer has leaped into the first draft intoxicated by the joy of the world she has created, only to be brought up short by something apparently minor which results in some ceiling gazing and mumbling things like, ‘I really hadn’t thought of that.’

One of these insidious little aspects of world-building often overlooked is the business of measurement – distances, lengths, weights, volumes and so on. Once you start writing your epic, you’ll be surprised to find how often we need to refer to such things. How far away is the enemy? How can you give some indication that your hero is lifting something really heavy? In your fully imaginary world, how do the residents measure their surroundings? And when they do, how do they refer to them?

You can try using comparisons – ‘She was as tall as a house and she could throw a stone twice as far as three big houses lined up one after another’ – but these quickly get tedious, and reader will soon feel like you’re avoiding something. If your fantasy world is going to be convincing (and that should be a fundamental aim) then your inhabitants won’t go around their everyday lives looking to compare things to elephants. Or wagons. Or dinner plates.

One can simply ignore this issue and have your plucky goatherd tell the barbarian warrior that the castle of his lord is ‘about six or seven kilometres down the road’ or note that your wise sorceress adds ‘fourteen milligrams of eye of newt’ to her potion. Some writers do just that, but I have trouble with this approach. I’m a supporter of the metric system, but when it always strikes me as too ‘this world’ and it tends to jerk me out of the narrative. It sounds too modern and scientific for a quasi-mediaeval, low tech Fantasy world. And that’s even though I know that the metric system is a good two hundred years old.

Another approach is to use an older system, one more rooted in tradition – the Imperial system of weights and measures. Having your knights talk in pounds and ounces, while your peasants measure their height in feet and inches has an in-built consistency and fits neatly. It all sounds wonderfully old-fashioned and authentic – to some of us. The trouble is that the Imperial system isn’t as out-dated and outmoded as we might think. The USA uses it today and so, to USA based readers, the Imperial system might not have the cosy ring of antiquity that sets a narrative in a land far-off and long ago.

Some writers advocate going to all the trouble of inventing new units of measurement, terms that sound exotic and other worldly. I’d advise against this. Partly because it’s a lot of work, and partly because it can be utterly baffling for the reader. It can lead to such things as ‘Krognor was a good six m’mmbeths tall and weighed 12 systlas while Jeezra was as well built as a forty-one garleth barrel.’

Even worse, we get convoluted efforts to try to explain these units. ‘The farm was four hagronds away, which was a day’s walk for a strong warrior or two day’s walk for a weakling, or a quarter of a day for a mail carrier on a horse.’

It’s a pity that this approach is fraught with difficulty, for the judicious dropping in of created words is a useful way of reminding a reader that they aren’t in the ordinary world any more – they’re in a Fantasy world where normal rules may not necessarily apply. Exotica can contribute to the background texture that is part of the joy of reading Fantasy.

I do have a suggestion, a way that combines the best of the approaches above and avoids most of their disadvantages: use obsolete, traditional measurements. These have the beauty of being somewhat familiar but are obviously the creation of a long-ago time. When a reader comes across them they are immediately taken out of the here and now. And they are often based on the physical world and so are easy to relate to.

Here’s a bunch of obsolete and outmoded units of measurement that might be useful. Some of them are splendidly evocative of other times. Drop them in appropriately and your readers will be transported, in a good way.

Distance and length

League – about three miles (nearly 5 kilometres).

Chain – about 20 metres.

Furlong – about 200 metres.

Rod – about 5 metres.

Fathom – about 1.8 metres.

Ell – about 1.1 metres.

Cubit – about half a metre (the measurement from fingertips to elbow).

Armspan – a bit less than two metres.

Hand – about 10 centimetres

Barleycorn – about 8 millimetres

Mass

Hundredweight – about 50 kilograms.

Stone – about 6 kilograms

Dram – about 2 milligrams

Pennyweight – about 1.5 grams.

Scruple – about 1.2 grams.

Time

Season - a quarter of a year (four winters had gone by …).

Volume

Tun – about 900 litres.

Perch (for masonry) – about 700 litres.

Hogshead – about 300 litres.

Barrel – about 160 litres.

Bushel (for dry goods) – about 35 litres.

Peck (for dry goods) – about 9 litres.

Dram – about 3 millilitres.

Area

Rood – about 1000 square metres.

October 24, 2013

Using Real, Historical People in Fiction

Writers have many challenges. Getting a pencil to a perfect sharp point. Coming up with alternatives to ‘Once upon a time’ to start a story. Finding time to count our enormous sacks of money. Things like that. With The Extraordinaires, my most recently released series I encountered a challenge that I hadn’t confronted before: the intricacies of using a real life character in a work of fiction.

One of the joys of writing fiction is being allowed to make up stuff. It’s fun, and when you’re a Fantasy writer, you get to make up huge bucketloads of stuff, which is extra fun. So when, for a change, I decided to set a book in the real world and include some real, famous people as characters, I had to do something different. I had to stick to the facts.

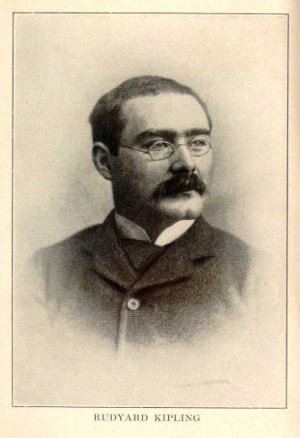

The main character of my story – Kingsley Ward – is totally made up, but in the course of the novel he runs into the real life author Rudyard Kipling, who is fascinated by Kingsley because Kingsley was raised by wolves.

The main character of my story – Kingsley Ward – is totally made up, but in the course of the novel he runs into the real life author Rudyard Kipling, who is fascinated by Kingsley because Kingsley was raised by wolves.

The connection, of course, comes about because of one of Kipling’s most famous creations - Mowgli, the hero of Kipling’s hugely successful ‘The Jungle Book’, who was also raised by wolves.

Naturally, I’m playing around with this connection between imagination and real life in my story as well as in my planning for the story, so to speak., but that’s another post for another day – as is the whole matter of children being raised by wild animals, something that I uncovered some fascinating material for during my research.

Once Kipling was part of my story, I had to find out as much as I could about him. He was probably the most famous writer of his time, widely read and respected, and a celebrity both in literary circles and the wider community. I could find plenty about his work, and his influences, and his interests, and details of his life were well documented. I needed something more concrete however – and this was a real sticking point. I could find out intriguing stuff such as his being an early motoring enthusiast, but I needed to something more basic. I need to know what he looked like.

It’s obvious, really, that writers need to know what their characters look like, and when we make them up this is a straightforward task. For real people, however, I had to stick to the facts. I had plenty of photos of Kipling, which were helpful, but I had trouble with one important detail, one that was vital for constructing a scene where Kipling is talking to someone. I needed to know how tall he was.

I sifted through book after book and found nothing. It’s funny, but Kipling’s friends and family didn’t really mention his stature, and Kipling didn’t bother to give us his height in any of his autobiographical material. I suppose it was mostly taken for granted, or considered unimportant. I was able to pick up little details about his mannerisms (priceless) and his speech patterns (equally priceless) but his height was elusive.

Finally, in a battered library copy of Kingsley Amis’s biography of Kipling, I found the following: ‘Physically, Rudyard Kipling was a small man. Five foot six inches is the official estimate.’ Eureka!

Finally, in a battered library copy of Kingsley Amis’s biography of Kipling, I found the following: ‘Physically, Rudyard Kipling was a small man. Five foot six inches is the official estimate.’ Eureka!

This just shows the power of research. Because as well as finding what I needed in order to present a faithful, authentic version of Rudyard Kipling, I stumbled across the name for my main character. Research. I love it because you can find what you need, but you also find the unexpected. Serendipity.

October 17, 2013

Five Top Alternate History Books

After my last post on Historical Fantasy was enjoyed by so many, I thought I’d walk across the line and look at Alternate History, especially seeing as I made the distinction between it and historical fantasy.

And just a word on the Alternate/Alternative debate. Frankly, I think ‘Alternate’ doesn’t make as much sense in this context as ‘Alternative’, and it may be actively wrong, but it seems to the be winner out there in internet land and, as we know, the internet is the arbiter in all things.

Quick definition – a story where one important premise is a change in an historical event that causes today to be different. The Jonbar Hinge (go on, look it up, I know you’re dying to) kicks off a different (alternative!) timeline providing authors with great story possibilities.

This sort of story is almost the classic ‘What if?’ jumping off point, from the obvious ‘What if the Nazis won WWII?’ to other, more obscure historical turning points.

In the list below, I’ve deliberately avoided any Nazis winning WWII stories. You can find them yourselves – there are plenty.

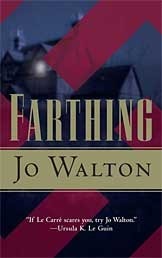

Farthing – Jo Walton

History diverges in the 1930s when the UK makes peace with Hitler before WW2. It’s a delicate, moving portrayal of a country that has compromised its soul. Anti-Semitism and fascism are rampant and the knowledge that nothing is being done to stop the Nazi atrocities is eating at the heart of the green and pleasant land. The first book of the Loose Change trilogy.

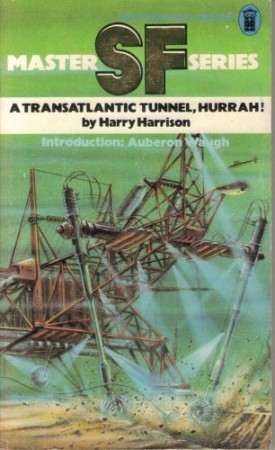

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah – Harry Harrison

One of my favourite books. History goes sideways when the Moors win the battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212 and the Iberian peninsula remains Islamic, changing the entire complexion of Europe. No Spanish expeditions to the New World, for one. The British discover America and gain such a hold that the nascent independence campaign is stifled and George Washington shot as a traitor.

One of my favourite books. History goes sideways when the Moors win the battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212 and the Iberian peninsula remains Islamic, changing the entire complexion of Europe. No Spanish expeditions to the New World, for one. The British discover America and gain such a hold that the nascent independence campaign is stifled and George Washington shot as a traitor.

The story takes up in the modified present day with the descendant of the traitor is the engineer in charge of the vast project to build a train tunnel across the Atlantic. Complications ensue in this proto-Steampunk gem, the book that the notoriously crusty Auberon Waugh (son of Evelyn) read and ‘cried like a baby at the wedding between the beautiful, good Iris and brave Captain Washington’.

Pavane – Keith Roberts

I first read this book a long time ago, and its elegant prose and subtle exploration of how changes could affect the course of the world has be coming back to it again and again. Roberts imagines a world where Queen Elizabeth I was assassinated and the English Renaissance never happened. Catholicism blanketed England, suppressing advances in science and philosophy, resulting in a much-stunted, much oppressed Britain. Elegiac, beautiful and sad.

I first read this book a long time ago, and its elegant prose and subtle exploration of how changes could affect the course of the world has be coming back to it again and again. Roberts imagines a world where Queen Elizabeth I was assassinated and the English Renaissance never happened. Catholicism blanketed England, suppressing advances in science and philosophy, resulting in a much-stunted, much oppressed Britain. Elegiac, beautiful and sad.

Joan Aiken – The Wolves of Willoughby Chase

This was a favourite of mine when younger particularly as it introduced the whole dizzy Wolves series which springs out of one vital historical event going sideways – the Stuarts win the Jacobite wars in the eighteenth century. The stories are set in a nineteenth century that results from this they are a fine example of this sub-genre.

This was a favourite of mine when younger particularly as it introduced the whole dizzy Wolves series which springs out of one vital historical event going sideways – the Stuarts win the Jacobite wars in the eighteenth century. The stories are set in a nineteenth century that results from this they are a fine example of this sub-genre.

The Gate of Worlds – Robert Silverberg

One of the master SF writers has turned his hand to AH with The Gate of Worlds, where the one of the present super powers is the Aztec Empire, because in the fourteenth century, the Black Death ravaged even more of Europe than it did in our timeline. A thoughtful, provocative adventure, which explore the notion of colonialism from a different point of view.

One of the master SF writers has turned his hand to AH with The Gate of Worlds, where the one of the present super powers is the Aztec Empire, because in the fourteenth century, the Black Death ravaged even more of Europe than it did in our timeline. A thoughtful, provocative adventure, which explore the notion of colonialism from a different point of view.

Satisfied or tantalised? Here’s three more, in brief, where I just sketch out the turning point. I’ll leave you to imagine the world that results.

The Alteration by Kingsley Amis. Instead of railing against Rome and starting the Reformation, Martin Luther actually becomes pope.

The Boleyn King by Laura Andersen. Anne Boleyn delivers a healthy son to Henry VIII!

Rominitas by Sophia McDougall. The Roman Empire never fell and endures today.

October 9, 2013

Five Great Historical Fantasy Novels

I’m happy enough with my Extraordinaires series

I’m happy enough with my Extraordinaires series  being called Steampunk, but I’m more and more coming to think of it as Historical Fantasy.

being called Steampunk, but I’m more and more coming to think of it as Historical Fantasy.

And by Historical Fantasy, I don’t mean Alternate History (stories in a world like our own that has taken a different historical path) or standard Fantasy that’s set in a world somewhat like our own except for added magic – (see my Laws of Magic for this).

I’ll take a stab a definition of Historical Fantasy, even though I understand that definitions are tricky: Historical Fantasy is a story set in an actual, definable historical time and location, but with elements of the fantastic included such as magic, gods or imaginary creatures.

Yes, it’s arguable and on the margins there are exceptions and ‘should be includeds’, but that’s the fate of every definition.

Historical Fantasy can be a real joy if you love Fantasy, but have grown tired of the standard Fantasy setting – a quasi-mediaeval, Northern European milieu. Historical Fantasy uses the best aspects of Fantasy in fresh, new places.

Here’s my list of Five Great Historical Fantasy Novels

Bridge of Birds – Barry Hughart

Oh, do read this book. Barry Hughart called it ‘A Novel of an Ancient China That Never Was’ and it’s an utter delight as Master Li (‘I have a slight flaw in my character’) and Number Ten Ox, his assistant, have a series of remarkable adventures in a magical landscape full of extraordinary characters. It’s rollicking, hilarious, suspenseful, eye-opening and the ending is both profound and moving.

Oh, do read this book. Barry Hughart called it ‘A Novel of an Ancient China That Never Was’ and it’s an utter delight as Master Li (‘I have a slight flaw in my character’) and Number Ten Ox, his assistant, have a series of remarkable adventures in a magical landscape full of extraordinary characters. It’s rollicking, hilarious, suspenseful, eye-opening and the ending is both profound and moving.

The Stress of Her Regard – Tim Powers

Tim Powers is one of the masters of Historical Fantasy. In The Stress of Her Regard he takes us early 19th century Europe and the world of the Romantic Poets. Shelley, Keats and Byron are substantial characters, and the remarkable night at the Villa Diodati where Mary Shelley created Frankenstein in the presence of Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and Dr John Polidori. This is the central part of a vast and brooding story that weaves in and out of the gaps in history. Sensational!

Temeraire – Naomi Novik

Temeraire – Naomi NovikNow we’re in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars, but with dragons. Do I need to say any more?

Soldier of the Mist – Gene Wolfe

One of our great speculative fiction writers, Gene Wolfe wrote one of the great Historical Fantasy books in Soldier of the Mist which is set in the Greek-Persian wars in the fifth century BCE. The main character suffers a head injury and so has amnesia – but he can also see gods, spirits and supernatural creatures. It’s a majestic book.

The Terror – Dan Simmons

Some might put this in the horror basket, but I’m going to appropriate it for Historical Fantasy, mostly because of the amount of research that’s gone into this cracker of a novel. It traces the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845, in which two steamships went searching for the fabled North-west Passage through the icy seas to the north of Canada. It’s no spoiler to tell you that everyone dies, for that’s the historical record. Simmons, however, uses chilling(!) Inuit mythology to explore a possible reason. It’s breathtaking.

Some might put this in the horror basket, but I’m going to appropriate it for Historical Fantasy, mostly because of the amount of research that’s gone into this cracker of a novel. It traces the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845, in which two steamships went searching for the fabled North-west Passage through the icy seas to the north of Canada. It’s no spoiler to tell you that everyone dies, for that’s the historical record. Simmons, however, uses chilling(!) Inuit mythology to explore a possible reason. It’s breathtaking.